The Vengeance Quilt

By DeAnna Knippling

Copyright © 2011 by DeAnna Knippling

Published by Wonderland Press

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

If you received this story for free and you liked it, please consider making a donation at WonderlandPress.com.

***

Table of Contents:

***

A sequel story to Chance Damnation, but can be read in any order.

God’s work weighs on Sebastian, a new priest, harder than most. But dealing with demons is his penance, and God never makes a burden harder than you can carry. Or so he believes when the rivalry between two of his parishioners spirals into the supernatural. A Weird West tale.

In his own head, he wasn’t Father Vincent Paul; he was Sebastian Jennings, a murderer. He hadn’t meant to become a violent man. He grimaced at himself in the mirror: now there was a face that would inspire his parishioners to love God. He checked his teeth, smoothed down his hair, and smiled. Even worse.

It was an August Saturday evening in the year of our Lord 1960, so he said Mass in his green vestments. He used to take more pride in his robes than any woman over designer dresses; now it was one more sign of his falseness under the glory of God.

He stepped out of the changing room. His older sister, Peggy, was waiting outside the door. “Sebastian? There’s a problem downstairs.” She wore an apron and twisted a wet towel in her hands. One side of her stylish dress was black from coffee or dishwater.

“What is it?”

“Claire and Eileen are fighting over the quilt for the harvest festival.”

“You should have interrupted me.” He rushed down the basement stairs.

Claire, a small woman with mousey hair, shouted, “That quilt doesn’t belong to you!”

Eileen, a much larger woman dressed in a tent, shouted back, “I paid for it!”

Claire Christiansen was married to Frank Christiansen, one of Don Hart’s hired hands. Eileen Hart was his wife. The two women stood in the kitchen with the service window shut, as if that would make them less audible to the people drinking coffee or the kids gaping from their catechism class doors. Sebastian held up one hand to keep Peggy from trying to smooth things over; he wanted to hear what the fight was about.

“You said the money was a donation!” Claire shrieked.

Frank Christiansen came toward the kitchen door, but Sebastian held him back, on hand on his chest.

“I hired you to make me a quilt!”

“You are the most selfish—I’m not going to say! I’ll give you back the money after we auction it off.”

“It’s my quilt!”

“Then just take it, you cow!”

“I’ll have your husband fired!”

“I just told you that you could have that damned quilt!”

Eileen noticed the others outside the kitchen door. Her blue eyes creased up at the corners. “You heard that, Father!”

“That’s enough, ladies,” he said. “You’re scaring the children.”

Claire turned around. She had a coffee cup and a towel in her hands; she put them down and walked toward him, her heels clicking precisely on the linoleum.

She glared at him with eyes so dark as to seem black. “There’s a commandment about those who bear false witness.” She went in the ladies’ room, slammed the door, locked it, then turned on the faucet, high-blast.

Eileen leaned back on a counter with a grin on her face.

Sebastian said, “I understood the quilt was a donation as well.”

Eileen said, “It’s my quilt. I paid for it.”

“Just for the materials?” Sebastian said. “Or for the time she spent on it as well?”

Eileen frowned. “That ain’t worth nothing. She owes me for lots of things. Milk.”

“I’d like to see an agreement for payment for her work, typed up and signed by both of you. And it would be very disappointing if I heard that Frank was fired over a disagreement between a couple of ladies.”

Eileen turned up her nose and lumbered out of the kitchen. She climbed the stairs slowly, dragging on the rail. “He could get fired for lots of reasons,” she shot over her shoulder, just as she turned the corner and went out of sight.

“Where’s Don?” Sebastian asked Peggy.

“Outside, smoking his pipe,” she said as Frank went back to his table, shaking his head. “I tried to get him to come in, but you know men. They don’t want to get involved.”

The corner of Sebastian’s mouth twitched.

Peggy shook her auburn curls. “Sorry, Father Vincent Paul. Ever since you started wearing black, I don’t know what to think of you.”

“Me, either,” he said.

Sunday went fine, and Monday he slept in late. When he woke up, he couldn’t remember whether he had enough hosts to last the next month, so he decided to check. He was out of coffee in the house, anyway. He wasn’t about to try to prepare for Bible study without coffee. Those ladies were sharp. Claire, especially, reminded him of himself in seminary; she chased down technicalities like a dog after a rabbit.

He unlocked the back door of the basement and flicked on the lights. He made it about three steps before he stopped. Nobody should have to face this before coffee.

The basement was blue with mold, except for a few steps of the green carpet on the stairs, including the lights and ceiling tiles. The smell made him sneeze and his eyes water. He cursed, made a mental note to confess his cursing later, and backed up the stairs. He put out the lights and locked the door behind him.

First he took off his shoes, dropped them in a bucket, and filled it with bleach water, which probably wasn’t good for the leather. Then he called Jim Blackthorn, his deacon. His daughter had had tonsillitis and been up to the hospital for the last few days.

Jim picked up the phone. “Hello? James Blackthorn speaking.”

“Don’t go into the Gray Hill church, Jim. The basement is covered with mold. Just covered. I’ll call the extension office in a minute. How’s Celeste Marie doing?”

“She’s sore, but she’ll be all right. I’ll tell her you asked about her.”

“Good to hear,” Sebastian said. “I’d come and visit, but I don’t want to make her sick.”

The County Extension Office promised to send someone out. Sebastian told them where he kept the spare key, in case he got called out. Then he remembered Claire and Peggy were supposed to clean the church that afternoon. He warned Peggy first. When he called the little Christiansen house, nobody answered, so he crossed his fingers and called the Harts.

A man answered, which was odd; it was August, and he should have been out harvesting wheat. “Hello? Hart Ranch.”

“Father Vincent Paul. I’m trying to reach Claire and tell her not to come to the church.”

“Father,” the man croaked. “Come right away. It’s Eileen. She’s doing poorly.”

“Certainly,” he said. “But will you pass on my message to Claire? The church is full of mold, and I don’t want anyone getting into it.”

“Mold,” the man agreed. “There’s mold all over the damned place.” He hung up.

When someone was doing poorly, you drove them to the hospital; you didn’t call the priest. Unless it was too bad not to bother with. Sebastian fetched his last rites bag. Then he raised the carpet in the closet, removed a section of flooring, and pulled out a lock box, unlocking it with a key he wore with a medal of St. Jude. Inside was a simple traveler’s Bible. He riffled through the pages with one thumb. The ink, swirls of brown symbols, was still intact. He added the book to the bag.

He drove over the hill and gasped; Hart Ranch shimmered blue in the late-summer sun. The shelter belt dangled with blue streamers. Haystacks rose blue out of blue drifts. Fields of blue wheat scattered blue fog. He stopped at the edge of the mold; part of him knew he’d already come too far, but he had a hard time forcing himself to drive forward anyhow.

He knocked on the door of the big farmhouse. Don Hart, tall and skinny and a good deal older than Eileen, opened the door. “Sorry, Father. Would you mind taking your shoes off?”

Sebastian slipped off his shoes and washed his hands in the sink.

The living room was full of a quilt frame stretched with the most colorful, delicately-pieced quilt he’d ever seen. Claire was stitching the top and bottom of the quilt together with a fine pattern of flowers. She had a foul look on her face.

Don passed by her without looking and went into his bedroom.

Eileen was lying in bed with her mouth open. Only two days had passed since he’d seen her last. Her gray skin had slid off her cheeks and into her neck; the blankets covered a good deal less flesh than they would have on Saturday.

“Has she been to the doctor?” Sebastian asked.

“Won’t go,” Don said.

Eileen’s breath rattled as she struggled to suck air past something in her throat.

“She was supposed to bury me,” Don said.

Sebastian pulled up a chair. “Eileen, Can you hear me? It’s Father Vincent Paul. You need to go to the hospital.”

Another rattle. Eileen’s head rolled back and forth. No.

“This mold is going to kill you,” he said.

No.

Sebastian sighed. “Do you want to make your last confession?”

Yes.

He chased Don out, started the rites, and asked her whether she had anything to confess.

She whispered, “That bitch is killing me.”

Sebastian leaned back. “You can’t mean that, Eileen.”

The fingers on her left hand curled toward him. He leaned toward her.

“Deal with the devil,” she hissed.

If anyone would use last rites to accuse someone of murder, it was Eileen; nevertheless, he was shocked. Sebastian placed the host, which was the kind that fell apart and could be swallowed without chewing, on her dry tongue. He touched the chalice of watered wine to her lips.

He finished the rites and made the sign of the cross over her. Then he backed out of the room, closed the door, and said to Don, leaning on the wall, “May I use your phone? I’ll be just a minute, and then I’d like to sit with her again.”

Don pointed toward the door to the living room. Sebastian sucked in his gut and walked around the quilt frame to the small table with the phone. He picked it up and dialed his brother Aloysius.

“Aloysius Jennings farm, Mrs. Jennings speaking,” Honey said.

“Is Aloysius in?” He glanced at Claire; her ear pointed at him like a third eye. “I want him out at Hart Ranch. Theodore too. I want them to take a look at something.”

“Something to do with the reason Peggy isn’t supposed to clean church today?”

Sebastian gritted his teeth to keep himself from grinning in front of Claire. That was Honey for you. “Maybe.”

“The walls have ears, don’t they? I’ll ride out and get them. Sit tight.”

When he finally left Eileen’s room, his brothers were waiting for him, sitting uncomfortably on the couch, almost underneath the quilt frame. Aloysius said, “Did you know that’s a Joseph’s Coat quilt pattern?”

Claire stitched without looking at her fingers. He could have sworn her eyes were black all the way through.

“Eileen’s dead,” he told her.

Claire nodded and went back to watching her fingers fly over the fabric.

He called the funeral home and told them the funeral would have to be in Fort Thompson because they were having a problem at Gray Hill.

“Sorry about the wait,” Sebastian said. Aloysius and Theodore stood up—“Ma’am”—and followed him into the hallway. Theodore handed around filter masks. “Ain’t got no goggles,” he said.

Outside was a wonderland. Part of him felt like it was the first snow of the season, pure and untouched; part of him knew it had killed one woman already.

Aloysius closed the door behind him. “Isn’t it funny that there’s no mold in the house?”

“You bring the book?” Theodore asked.

Sebastian tapped his pocket.

“It’s not the demons again, is it?” Aloysius asked.

“No,” Sebastian snapped. “I swore I wouldn’t do that again.”

“I didn’t say you had,” Aloysius said. “Where should we start looking?”

“Where it’s wet,” Theodore said.

Aloysius pulled a stick off a tree and wacked at a big blue branch, scattering mold.

“Knock it off,” Sebastian said.

“Couldn’t help myself.” Aloysius pointed at a big stand of trees. “If I remember right, the stock tank is over there. Garden on one side and the corral on the other.”

They walked through the mold, Aloysius scuffing his feet and kicking up spores. Sebastian just let it be. There were two lumps lying under the mold in the corral.

They walked toward the water tank, which was covered with mold, like everything else.

“What are we looking for?” Aloysius asked. “What’s that?” He pointed at a pattern in the mold on the fence above the tank. Theodore wiped the mold off it with his bare hand and tried to shake it off. He ended up wiping it on his pants.

It was one of the symbols from the book. Sebastian said, “It’s a summoning symbol.”

“Summoning what?” Aloysius asked.

“Whatever wanted to come,” Sebastian said. They went back to the house. That, Sebastian thought, was too easy.

Aloysius stopped them outside the door, opened it, and yelled, “Mr. Hart!” He waited a few seconds. “I’m sorry to bother you, but there’s something you should know.”

A door opened, and Don walked toward them. He didn’t bother to wipe his face.

Aloysius said, “We’ll have to evacuate; the milk cows are dead already. I’m sorry, Mr. Hart, but you may lose the farm.”

From the living room, Claire shouted, “No!” She appeared at the door to the entryway.

“It’s up to the Extension Office,” Aloysius said. “There may be nothing for it but to kill everything on the farm. Come on, put your shoes on. Is there anybody else?”

“Frank,” she said. “He went out this morning—” Her tiny knees folded up under the hem of her dress, and she sank onto the floor.

Don said, “What about my wife?”

“We’ll take her with us,” Aloysius said.

Sebastian had Theodore help wrap Eileen Hart in blankets. There was a time when he would have turned his nose up at carrying a dead woman in his arms but not anymore. The two of them carried Eileen, Theodore under her shoulders and Sebastian at her feet, to the back of Theodore’s pickup truck. She stank already, or maybe it was the room.

“You take Don,” he told Theodore. “I’ll take Mrs. Christiansen. You look for Frank,” he told Aloysius. “And burn your clothes and spray your trucks down with bleach or vinegar, for God’s sake.”

“He’s in the north pasture by the creek,” Claire murmured. She swayed, and Sebastian grabbed her by the arm. He bit his tongue and walked her toward his Buick.

“Claire,” he said, hands at ten and two. “What did you do it for? We found the summoning symbol on the water tank.”

“The what?” Her hands were folded in her lap; she sat as straight as a fence post.

Sebastian drew the symbol—incompletely—in the dashboard dust. “That.” He brushed it away.

“Oh, that,” she said. “That was the water tank last Saturday. Is it a hobo sign?”

“Claire, we priests study many things at seminary, one of which is devil worship. This is one of their signs.” He was distorting the truth; another item for his next confession.

“Devil worship,” Claire said. “You mean it’s real? Eileen had a Bible with all kinds of weird things like that in it. In her bedside table.”

Sebastian stopped at the stop sign. “I’m going to take you to my father’s farm.”

“But that’s back the other way.”

“So it is. Peggy’ll take care of you.” He turned the car around.

Claire didn’t say anything for the longest time. “What’ll me and Frank do?”

“We’ll take care of you,” he promised.

“We, as in the church, or we, as in the Jennings?” she asked. “I don’t want any handouts.”

“Probably the latter,” he admitted. “My father could use help, now that Aloysius is on his own. And Peggy wouldn’t mind the company.”

Claire put her pointed chin in her elflike hand on the window ledge. “I wish we’d known that. I would have dragged Frank off like a shot. That woman hated me. Did everything she could to make my life miserable. We didn’t know there was anyplace else to go.”

He didn’t have any answer for that.

Sebastian left Claire with Peggy, who shoved him out of the house with a broom and told him to get his Buick away from the elms. He drove back. A white van from the Extension Office was parked at the Hart Ranch farmhouse. His friend Jasper stood next to it with a paint-fume mask dangling around his neck, smoking an unfiltered cigarette. Sebastian shook his hand. “Jasper.”

Jasper Long Horse was a jack of all trades in Buffalo County. He’d grown up on the reservation, gone to school in Sioux Falls, and had come back to work for the county as a repairman, tree-remover, snow-plower, killer of rabid dogs and coyotes, and agent of the County Extension Office. What he’d come back for, Sebastian had never been sure.

“What the hell, Sebastian, I mean Father?” he asked.

Sebastian chewed on a nail, then realized he was contaminating himself more than he already was. “Would you think I was crazy if I said it was black magic?”

Jasper let it go. “The inside of that house is untouched. I don’t get it.”

“You saw the church?”

“Sprayed it down. With any luck, you should have the place back by next Saturday. But this place, I don’t know.”

“I left something inside. Mind if I go in?”

Jasper waved him toward the door. “Be my guest.”

Sebastian found the book where Claire had told him, the same kind of Bible they’d used in seminary. He stopped in the living room to take another look at the quilt. The blocks seemed like random patches of different colors of scrap, sewn together any which way, but if he looked at the quilt as a whole, he could pick out patterns. Then he took another look at it and swore (another item on his list). The stitching wasn’t of flowers; it was protection symbols.

No wonder why Eileen wanted the quilt.

He unclamped the quilt from the frame put it in a trash bag, and brought it with him.

Jasper peeked inside the bag. “Whatchoo taking that blanket for?”

“It was supposed to be a donation for the church at the Harvest Festival next month,” Sebastian said. “I don’t want anything to happen to it. Don’t worry, I’ll have Peggy wash it.”

“You should get a lot of money for that,” Jasper agreed. He got in the van, and Sebastian followed him off the farm. Jasper stopped, rolled his window down, and waved him over to the side of the road. “Don’t tell Don and them, but we’re going to have to spray everything. Might have to go into your dad’s property, too.”

“Do what you have to.”

Jasper nodded. “I get the mold and you get the black magic, all right?”

“Deal.”

Jasper laughed, rolled up his window, and drove away.

He threw down the quilt in front of Claire, who was sitting on the couch next to Peggy, wearing a dress about five sizes too big. “You lied to me. That flower pattern is a protection symbol.”

Claire ran her fingers over the stitching. “It’s just a nice design.”

Sebastian said, “What I don’t understand is how, if the house was protected from the mold by this symbol, Eileen could die of it.”

Someone coughed from behind him. Sebastian turned and saw Frank Christiansen holding his cowboy hat in both hands. “It wasn’t mold,” he said. “It was cancer.”

Claire looked up at him over the stitching. “How do you know?”

“I knew,” he said. “She’s been hiding it for a long time.”

Claire pressed her lips together.

“Don’t blame Claire,” Frank said. “I told her to put the symbols on the quilt. I’m sorry. She was going to get me fired. I had to do something to make myself look too good to get rid of. But it was too strong for me.”

Claire stood up, dropping the quilt, and went into the kitchen. “That bitch.” Sebastian heard drawers rattle and slam. He followed and saw her with the top of her dressed pulled open, holding a paring knife against her chest. She was covered in blood; she had carved the symbol from the water tank on her chest, upside down.

Sebastian looked away modestly from her naked breasts, then told himself to stop being an idiot. He tried to take the knife away from Claire; she shoved him. She was too small to make him lose his balance, but she stumbled out of arm’s reach anyway. She stretched her neck, making a twisted face in order to see better. She touched up one of the lines with the knife and tossed it on the counter.

“Goodbye, Father Vincent Paul,” she said.

Frank was standing beside him. “Claire. Wait.”

Without turning around, she said, “How else could you have known about that Bible? By her bed? She never told anyone about it. You saw it, you cheating son of a bitch.” The back door slammed and the screen door creaked shut after it.

By the time they nerved themselves to follow her outside, she’d roared down the road in Frank’s truck. Fortunately, it hadn’t rained in a while, and they could follow the dust trail. Frank pushed on the dash, trying to make the Buick drive faster.

“Do you know where she got the book, Frank?” he asked.

“Of course I didn’t want to. Have you seen how beautiful my wife is? But Eileen told me we’d lose our home if I didn’t.” Frank had left his hat behind, and the sun was shining straight into his wide, blue eyes.

“The book, Frank. Where did Eileen get the book from?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “She just had it.”

“Does Don know about it?”

“He didn’t go rummaging around in her bedside table.”

They turned onto the Hart Ranch road and found the pickup truck abandoned beside the road. The door had been twisted off its hinges. He swore again and decided to stop keeping an itemized list of his sins.

On foot, they followed the trail through the grass, stopping just past the mold. The mold crept toward them; Sebastian stepped back, but Frank started to ran into it. Sebastian grabbed his arm and swung him around so hard he ended up on the ground. Frank hissed at him, got up, and ran into the blue.

It wasn’t quite as blue as it had been earlier. More of a soft gray.

Frank ran down the hill, mold covering him from head to foot as he kicked up spores, until he disappeared into a tree belt.

He’d failed them again—God, family, parishioner, and neighbor—and there wasn’t anything else he could do, so why he gunned the engine and sped down the hill toward the farmhouse, he never knew. He parked the Buick, pulled the revolver that Theodore had given him out of the glove box, and loaded it.

He found Frank by the milk barn, almost at the stock tank. The mold covered him as Sebastian approached him; the blood splatters turned blue and disappeared. One of the three mounds in the pen reared up and hissed at him.

Claire.

“Don is dead,” he lied. “Heart attack. It’s over. There’s no more vengeance to be had.”

The summoning symbol had worked, all right. She was more like a knee-high snake than anything else, but with several small, warped limbs. Her chin puffed out like a frog’s, so close to him that he could have reached out and touched it. Greenish, spotted, tiny gold-colored eyes.

Claire opened her mouth, sorted through the mold with her long tongue, and pulled out one of Frank’s legs. She gulped it down whole. Sebastian backed toward the stock pond, pulled out a pocket knife, and started to gouge out the summoning symbol.

Claire spat out bone and rushed at him. He had a split second to decide between shooting Claire or not. Instead he jumped backward as Claire smashed, face-first, into the symbol on the fence. How she’d cleared the stock tank with her spindly limbs, he didn’t know.

The fence shattered, breaking the symbol. If Sebastian was expecting a miracle, he wasn’t going to get one; the mold certainly didn’t disappear or turn into daisies. Claire backed up, shook her head, and tried to charge him again.

He pulled out the revolver. “Sorry, Claire.” He shot her on the head, which stunned her for a moment; then he rolled her on her side and shot her in the chest, ripping the summoning symbol there to shreds.

Quick as anything, he dropped the gun, pulled out his penknife again, and carved the protection symbol onto the first whole piece of skin he found. She shuddered and thrashed, knocking him down. He grabbed onto her, and carved, from memory, the symbol for banishing, over and over, until she lay still.

He asked God to forgive them and receive their souls, sinners all.

Aloysius kept Jasper from sending in the crop dusters until he and Theodore had dragged Sebastian, Claire, and Frank out of the mold.

“Holy shit,” Jasper said, when he pulled back the tarp and saw Claire underneath. Whatever she’d called inside her was gone, but it hadn’t left her gently. Her jaw was shattered, and her skin was stretched out so badly that Aloysius had barely been able to carry her back to the truck for all the flopping around she did. No two bones seemed to be stuck together, and of course she was covered with bloody symbols. And then there was Frank, in pieces.

“Eileen Hart blackmailed him into cheating on Claire.” Sebastian coughed up gray phlegm. “Claire decided to take revenge on him since Eileen was already dead. But I didn’t tell you that.”

“Black magic,” Jasper said. “Shit.”

“I took care of it.”

Jasper gave him a look. It was the first time Sebastian could remember that anybody had looked at him like he was a real, live priest instead of a kid whose diapers they’d changed or who had last been seen guzzling beer out on the reservation.

The mold was obviously dying, turning a flat gray, but nobody wanted to risk it, so Jasper sent in the crop dusters with heavy-duty fungicide. They’d been lucky. Don Hart took his savings and moved to Minnesota, near one of his daughters by his first wife. Liam bought the farm and hired more men to work it; the land grew well enough after a few years had passed.

Peggy finished the rest of the quilt using the protection symbol, and they sold tickets for it at the Harvest Festival. Sebastian put in twenty bucks and won it.

He put it on his own bed and slept very well indeed.

***

From Wonderland Press and DeAnna Knippling

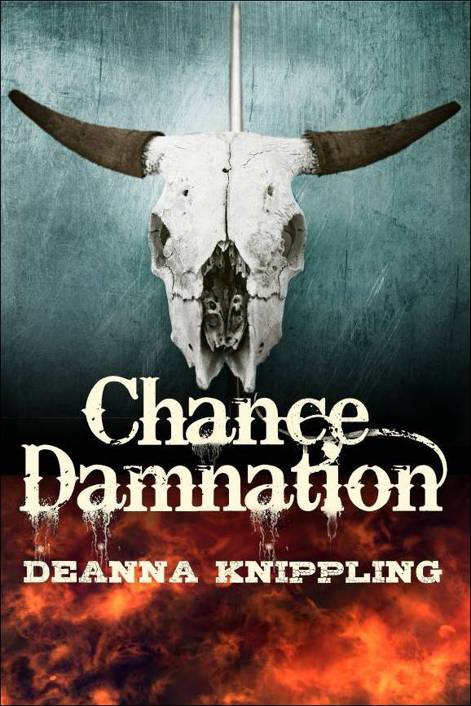

Chance Damnation

By DeAnna Knippling

One little girl. Buffalo-demons stampede out of the earth to steal one little half-blood girl, and everything changes. Aloysius’s little brother Jerome goes missing with her–two inseparable kids whose friendship is damned from the beginning–as demons replace the newly dead.

A priest with a tainted Bible. A brother with a taste for blood and demon flesh. A fool with a passion for the machinery of Hell. Only Aloysius and his brothers can see the transformation–and there’s not a damned thing they can do about it. Then Jerome returns: he has found a way down into the demons’ Hell, where they twist the little girl’s tortured dreams into a paradise of their own, a place to escape the demons who, in turn, haunt them.

Chapter 1

Buffalo County, South Dakota, 1960

Jerome stared up at Celeste Marie on the top of the pile of dirt outside the church in Gray Hill. She was standing with her hand shading her eyes from the sun, and the wind was blowing her shining black hair. They were both just kids—fifth graders—but someday, he was going to marry her, and there would be problems.

“Look,” she said.

“At what?”

“Over there.” She pointed at something on the other side of the hill.

Jerome climbed to the top of the hill beside her. His feet sank into the loose dirt, dried to a crust on top with wet clay just underneath. They were running water from the new well to the church, and there were trenches and pits in the ground all over the place.

Jerome shaded his eyes and squinted, but it was no good. He’d left his hat inside the church, and he couldn’t go after it or his father or somebody would remember it was time to go home and sit at the long table for dinner and say “please” and “thank you” and “excuse me” and “may I go now?” Yet his blue eyes were no good in the sun.

“What is it?” he asked.

“A demon.” She stood on tiptoe, grabbed his arm.

“There’s no such thing as demons. It’s a bull.”

“It’s not a bull. Too many horns. Oh!” The dirt shifted from underneath her, and she slid down the hill. She tried to grab his arm but lost hold.

The dirt shifted under Jerome, too, and he tried to both stop himself from falling and grab Celeste Marie at the same time. All of a sudden, he knew they were in danger. It wasn’t a question of looking back later and wondering if he had known; he knew.

“Run!” he shouted.

The dirt shifted again and he went down on hands and knees, sliding to the bottom. He pushed backward from the dirt hill and got to his feet. The ditch where the pipes were going to be buried was between him and Celeste Marie.

Celeste was standing up again and staring into space. “Look at them run!”

That damned girl. He carefully checked the ground, then jumped over the ditch and pulled her by the back of her shirt. “Come on, Celeste Marie.”

The dirt hill was starting to fall down like a milkshake being sucked up from underneath. Jerome pulled Celeste Marie away from the hill, toward the cemetery. Not that the cemetery was important; that’s just where the one safe direction was, for the moment.

He didn’t run, and he didn’t do any more shouting. He led Celeste Marie among the graves to the big statue of Jesus kneeling. They’d be safer back there, out of sight.

“We have to go back,” Celeste Marie said.

“What for?”

“We have to get in the back of Peggy’s pickup truck and have her drive us out of here before the demons check the graveyard.”

Jerome sighed—she couldn’t have said something two minutes ago?—and led her back toward the church’s gravel parking lot, stopping behind his sister Peggy’s pickup truck so they couldn’t be seen. He peeked through the dirty window toward the church. The hill was a hole in the ground now. Jerome shaded his eyes and saw something moving underneath.

From the front of the church, Mr. Blackthorn hollered, “Celeste Marie!”

Celeste Marie jerked like she’d just got woken up and started to take a breath. Jerome slapped a hand over her mouth.

From the dirt hole, something grunted.

Jerome murmured in her ear, “I ain’t ready to get killed yet, are you?”

Celeste Marie shook her head.

“Let’s pretend we didn’t hear your dad.”

Celeste Marie grinned around his hand. Her sweat smelled like bread, and he could feel her big front teeth under his fingers. He let her go.

“Okay,” she said. “But only for a little while. Until the demons are gone. They’re right over there.” She stepped out from behind the truck to point into the wheat field with her brown stick arm.

Jerome jerked her back behind the pickup truck. “You got to be better at hiding than that.”

Celeste Marie giggled as Jerome peeked from behind the back of the truck. Sure enough, the field was scattered with black dots running toward them, whatever they were.

Jerome coughed as an evil smell got up his nose and stung his eyes. Something grunted behind him. When he turned around to see what it was, he saw that he was face-to-face with something big, black, and ugly. Celeste Marie stared up at it as it reached for her.

Jerome dragged Celeste Marie out of the way and around the truck. Big Ugly was naked and hairy, with four curling horns and a big snout, and he walked on two legs. He followed them for a second, then doubled back around with his hands outspread, waiting to see which way they would go.

Jerome pushed Celeste Marie into the side of the pickup truck, grabbed her legs, and lifted her up. She bent at the waist and toppled into the truck, protesting: “This is a terrible place to hide.”

Jerome put his boot on the tire and boosted himself up behind her while the black thing circled toward them. There was a tarp in the back of the truck, held down with the cans of green paint and linseed oil they were using to paint the roof. Jerome pulled the tarp over Celeste Marie, in case it happened to do any good, picked up a gallon can of linseed oil, and swung it, hard.

If it hadn’t hit the demon, it would have smashed the back window of Peggy’s pickup truck, and then he would have been in trouble. But the full can hit the demon with a thump and bounced back. Jerome let the weight of the can carry it over his shoulder; then he swung the can over his head. The thing bellowed as the can cracked one of his horns.

“Celeste Marie!” Mr. Blackthorn shouted again. He sounded cross and impatient. He probably wanted her to go inside to help dust the pews or clean fingerprints off the windows or something.

“Coming!” Celeste Marie shouted. She struggled under the tarp and pushed it back.

Big Ugly was touching his horn and shaking his giant, shaggy head. He started to grab for Jerome, but Jerome swung the can again, and it knocked the demon’s muscled, hairy arm aside. Big Ugly growled and reached for him again.

More time.

Celeste Marie screamed. Her tiny body threw the heavy tarp out of the pickup truck and into Big Ugly’s face; then she pummeled the thing with the meat of her fists. “Leave him alone!”

Jerome would have laughed at how angry she sounded and how futile it was for her weak arms to pound at the demon if the demon hadn’t been big enough to pull her out of the truck bed and throw her to the moon.

“Celeste? Celeste Marie!” Mr. Blackthorn’s shouting sounded far, far away. Jerome shoved Celeste Marie out of the way.

The demon roared and the smell got worse; it was as bad as rotten Christmas oranges in July or Easter eggs in August.

Celeste said, “So that’s how you do it.” Jerome looked down; she had one of the cans of paint open and waiting. As far as he could tell, she’d used her bare hands to open it with. She picked up the can and held it carefully by the handle.

The moment Big Ugly stripped off the tarp, she hurled green paint into his eyes. The paint splattered the demon and splashed back over their church clothes.

“Hah!” Celeste Marie said. Then she shrieked as another one of the demons caught her from behind, right around her waist.

Big Ugly bellowed as Jerome leapt from the truck bed toward the second demon. He missed, as he knew he would, and landed on his knees. He got up and ran after the thing, which was running with Celeste Marie toward the dirt hole.

Jerome had a metal fence post in his hands; he didn’t know where he’d got it from, probably from the back of the truck. His arms didn’t want to move right, it was so heavy. He swung and missed. He swung again and hit the demon, right in the back, but the demon didn’t stop. The post was too heavy to swing again, so he charged with it, slamming it hard into the demon’s back, right at the spine.

The demon stumbled, dropping Celeste Marie and leaping over her, then skidding into the ground. Jerome followed and hit him again with the post, at the bottom of his neck this time. The post slid along its neck and got stuck in the crack between the top of his neck and the bottom of his head.

The demon went down on its knees. Celeste Marie kicked the demon with her sandals, and Jerome jerked the post out and swung hard, hitting the demon in the back of the head.

The metal post anchor got stuck in the thing’s head, and Jerome wasn’t strong enough to jerk it out this time. He screamed with the need to hurry.

Then someone was pulling him backward. He kicked and twisted but couldn’t escape. The next thing he knew, he was inside his sister Peggy’s truck with Peggy on one side and Celeste Marie on the other. He almost slid off the seat into the dashboard as the truck whirled out of the parking lot.

Celeste Marie stared at him up and down, hanging onto his arms with her tiny hands. “You’re green.”

Jerome looked around. Peggy was driving them down the gravel road away from church, which was surrounded by demons.

There was smoke.

Chapter 2

Aloysius said, “The way I figure it, Sebastian, what you just said makes you an idiot. Why don’t I just ignore what you said, so you can go back to being a man of God instead?”

They were standing in the vestibule, long after mass had ended. Even the old ladies had gone home, mostly. He’d been trying to get his little brother Sebastian alone, so he could congratulate him on his ordination, but their ability not to get into each other’s sore spots hadn’t lasted five minutes.

“Stop calling me Sebastian. It’s Father Vincent Paul now. And stop pretending you’ve forgotten.” Sebastian brushed a wrinkle from the front of his green vestments, which were shinier with gold thread—and quite a bit cleaner, to be honest—than Aloysius’s shirt and slacks. The black shoes sticking out from underneath his vestments were polished to a bright shine, while Aloysius knew his shitkickers had a few spots of mud on them at the best of times.

Aloysius said, “I don’t keep track of ladies’ married names until they last two years or start having babies, and I ain’t keeping track of your priest name, either, until I know you have what it takes to make it stick. Frankly, if our father heard what’s coming out of your mouth, he’d bend you over his knee and wallop you. I’m tempted to do it myself.”

Theodore, learning against the wall and waiting for Aloysius, walked to the doors of the church itself and shut them so Jim Blackthorn, the deacon, couldn’t overhear Aloysius being disrespectful to a priest.

Unblinking behind his coke-bottle glasses, Sebastian said, “Our father agrees with me. As does the Federal Government.”

“Bull,” Aloysius said, reluctant to swear in church, even if only in the vestibule. “Taking away somebody’s land ain’t right. Next thing you know, the government’s going to take our land, too. If what you say is true, which I doubt, Father shouldn’t of put up with it. And I don’t care what the Feds say anyhow.”

“He sent a letter to the Governor in support of it.”

“I don’t believe it,” Aloysius said.

“He did,” Theodore croaked. Between the cigarettes and the lack of speaking, he sounded like a damned frog when he did open his mouth. “I heard him talking about it the other day.”

Aloysius shook his head. “It ain’t right.”

“You’re the only one who thinks so,” Sebastian said. “It’ll bring a lot of business to the area.”

“What do we need with business?” Aloysius asked. “We’re a bunch of ranchers, not a city-bedamned-council.”

“Hydroelectric power will—”

“They’re just going to send it out of state.”

“And the irrigation.”

“I don’t want no corn farmers out here anyway. This is cow country. Hay. Wheat. Alfalfa.”

“And the flooding.”

“That’s rich,” Aloysius said. “You’re going to tell me the best way to stop flooding is by flooding the whole area?”

“Aloysius, they’re going to put in the dam whether you or the Indians like it or not, and that’s the end of it,” Sebastian snapped. “So stop arguing with me. Go argue with someone who gives a...” He snapped his lips shut. His hands were shaking inside his big sleeves.

One of the doors into the church popped open, and Jim Blackthorn stormed out. At first, his chest stuck out and his brow roiled like a thunderstorm. But when he saw the brothers in the vestibule, he shrank into a hunched-over excuse for a scrawny weakling.

“Oh, excuse me, excuse me,” he said. “I didn’t mean to interrupt. You haven’t seen Celeste Marie, have you?”

Aloysius hated the bald-headed, slick-faced Indian, vicious and mean to his daughter and his white wife (at least he had been, before she’d left him) and to the other Indians who came to service, but groveling to other whites and the priest. Sebastian used to hate the man, too; at least he used to say so, before he came back from seminary. Now they were thick as thieves.

Aloysius shook his head. “Nope, ain’t seen her.”

Theodore grimaced, which meant the girl was probably outside playing with their youngest brother, Jerome. Their father, Liam, didn’t approve of Jerome mixing with the half-blood girl. Neither did Jim Blackthorn. Aloysius couldn’t understand it; she was a good kid for all her father’s flaws. A little odd was all.

Come to think of it, Aloysius was almost willing to believe the old man was willing to overlook the injustice of flooding out Indian land to build a dam. Liam didn’t give a good God damn—so to speak—about the Indians, but Aloysius had thought that he’d have been up in arms at the thought of someone losing their land to the government.

Sebastian said, “She ran outside with all the other kids after service, James.”

Mr. Blackthorn scowled. “She’s supposed to be cleaning the church. She’s old enough to help.”

Sebastian said, “Why don’t you give her a holler, James? I’m sure she’ll be right in.”

Jim stepped outside and shrieked, “Celeste Marie!”

After a second, when she hadn’t answered, Jim said, “That girl. When I see her, I’ll—”

“You’ll what, Jim?” Aloysius asked. “Whip her with a switch?”

Theodore rolled his eyes, as if to say, There he goes again.

But Aloysius had been in enough trouble already to know that he didn’t mind making a few enemies now and then.

Jim Blackthorn almost steamed with rage. “Celeste! Celeste Marie!”

Sebastian said, “Now, Aloysius, that was uncalled for.”

Aloysius snorted. “Why didn’t you say it? You’re our man of the cloth now. Aren’t you supposed to be keeping an eye on us sinners and making sure we follow the straight and narrow? And not beating our daughters?”

“When I have something to say to Jim, I’ll say it in the confessional, Aloysius.”

—He had a point there.

Aloysius said, “How did you get assigned here anyway? You ain’t supposed to be priest for someplace you grew up in, I know that much.”

Sebastian’s eyebrows were a solid stripe across his forehead. “I’m starting to agree with you,” Sebastian growled. “I’m going to change.” He whirled around, his vestments flaring as he stormed into the changing room. The door slammed, trapping the hem of his vestments.

Aloysius grinned while the green cloth jerked in the doorway like a live thing. Then the door opened and the cloth disappeared. The door slammed again.

“You got to lay off him, Aloysius,” Theodore said.

“What for? Is he going to stop acting like a—excuse me—like an arrogant—” Aloysius had trouble thinking of an appropriate term, here in church. He continued, lamely, “If I don’t remind him from time to time?”

“He didn’t want to come back here either,” Theodore said. “It was Father who set it up. Made him do it. Wanted to be proud of him. You ain’t helping.”

Aloysius hissed through his teeth. “He should have married that nun instead.”

Theodore said, “What’s done is done.”

Aloysius had forgotten about Jim Blackthorn standing near the doors until the man yelled, “Celeste Marie!” again.

Aloysius sighed. “I’ll go help you look for her, Jim.”

“That’s all right. I don’t mean to interrupt you.”

“You already did, Jim.”

For a second, he could have sworn that Jim Blackthorn’s eyes lit up with a wicked glee. Well, if that was all the pleasure the man could get out of life, so be it.

There was a crash from the basement, and Aloysius tried to remember if his sweetheart Honey Lindley was still down there with Theodore’s wife Maeve.

“What was that, the pipes?” Aloysius said.

There was another crash and a terrible groaning sound from inside the church, like the ground itself was in pain, and Theodore took off running down the stairs.

“Celeste Marie!” Jim Blackthorn screamed out the front door, sounding more worried than angry now.

Aloysius grabbed the man and pulled him out of the church. Honey was outside, standing next to his sister Peggy. They were both staring at him. Or rather, at the church.

“What was that, the pipes?” Honey said. “Aloysius. What did you do?”

Aloysius turned around and ran back for the church. “Anybody know where the kids are?” he yelled over his shoulder.

He didn’t hear the answer. The inside of the church was moaning and groaning, a million angry ghosts tearing it apart. The glass in one of the new windows broke and slid down to the floor in a dozen pieces of scraping glass.

“Sebastian!” he shouted. “Anybody! Sebastian!” He banged on the door to the changing room; it swung open, empty.

As he charged through the church, the floor shifted underneath him and he grabbed onto a pew. Earthquake? Maybe it really was the pipes. They’d just started installing running water at the church, digging the holes for the lines themselves, trying to get the pipes sealed up without leaking too bad. Aloysius had been helping lay the pipes on Wednesday, and he offered up a quick prayer: Lord, I will keep my da—my mouth shut if only you will make whatever I screwed up not quite so bad as it could have been. Amen.

He’d just made it past the altar and into the sacristy when the floor crashed behind him. He couldn’t help it: he stopped to look.

The floor had split almost straight down the middle of the church in a jagged hole about five feet across. Floor beams stuck into the hole like rotten teeth. The carpet runner down the center aisle dangled into the hole.

Some of the pews in the middle of the church started to slide across the floor toward the hole. The feet of the pews scraped up the carpet tacks, and the carpet toppled into the hole.

Aloysius could see the lights still on in the basement; a woman was screaming. Had he seen Maeve outside? He couldn’t remember. The lights went out.

“Theodore!” the woman screamed. It must be Maeve. For a second, Aloysius hoped it was. He didn’t like the woman and suspected her of being a gold-digger. Then he realized that it must be his fault she was down in the basement screaming and felt ashamed of himself: he was a disagreeable man who hated almost everyone, and he was going to hell.

But then again, he’d be damned if he was going to confess that to his little brother. If he lived through this, he was going to drive up to town and find somebody else to hear him out.

Aloysius felt a hand on his shoulder. He turned around and saw Sebastian standing behind him in black shirt and trousers.

“Don’t tell me it was the pipes,” Aloysius said.

Sebastian shook his head. “Did you hear that?”

Aloysius couldn’t hear anything other than Maeve yelling and the sound of his own heartbeat in his ears. He shook his head, then stopped—no, he had heard something. A grunt.

Another grunt.

A sneeze.

“What is that?” Aloysius said.

“Shh.”

He squatted down, trying to get a closer look into the darkness. He thought he saw a machine of some kind with a dark shape walking away from it.

“A buffalo?” he whispered. “How did a buffalo get into the damned basement?”

Sebastian grabbed his arm and dug in.

“Ow,” Aloysius said.

“Shht!”

What sounded like a hundred hooves struck on the basement floor. Maeve’s screaming changed pitch from outrage to panic, then cut off. Sebastian and Aloysius looked at each other.

Sebastian whispered, “Lord, give me strength.” He grabbed Aloysius by the shoulder before he could jump into the hole. “Use the back stairs, idiot.”

They both took off running into the sacristy, and from there, the basement.

Chapter 3

Aloysius ignored the smell—it wasn’t any worse than a cattle branding—but Sebastian choked on it and covered his face with a handkerchief.

The cement stairs had cracked, and going down them was more like sliding than like climbing. He tried to be as quiet as he could, but he couldn’t see that it would make much difference: whatever it was in the basement was making an awful racket, growling and grunting and stomping.

Aloysius slid to the bottom of the stairs and peeked around the corner.

The whole basement was full of, well, demons. He didn’t know what else they could be. They were about seven feet tall, with hooves, horns, and heavy black hair all over their naked bodies.

“Hell,” he said.

Sebastian grabbed onto the back of his shirt and pulled him back into the stairwell.

The demons were making a big ruckus down there, and dollars to donuts, they were going to be looking for a way out. Aloysius was pretty sure the stairwell, no matter how busted up it was, was going to be the last place he and Sebastian wanted to be.

Maeve screamed again. This time, it wasn’t anger or fear in her voice, but a terrible pain, the sound of a cowboy getting rolled under his horse.

So he got hold of Sebastian peeked around the corner toward the kitchen. Either Maeve would be in there, or she wouldn’t, and they’d be able to figure out where she was from the service window.

Maeve shrieked again. The demons turned toward the noise, and Aloysius and Sebastian ducked back toward the kitchen. The door was blocked, but the board that covered the serving window had fallen off, so they rolled through the hole and dropped to the floor.

“Where are the knives?” Aloysius asked. He almost had to yell to be heard as he grabbed at drawers, pulled them open, and swished his hand around in them. The place was pitch dark and the floor was all cracked up.

“I don’t know,” Sebastian said.

“It’s your kitchen.”

“The ladies don’t let me in here.”

Aloysius grunted and jerked his hand back: he’d found the knives. “Got ‘em. Dull as dishwater.”

Maeve screamed again. Aloysius found Sebastian’s open hand and put a bread knife in it. He kept a couple of big knives for himself.

“What am I going to do with a bread knife?” Sebastian asked.

“Same thing as I am. Damn the luck for not having a shotgun.”

“I can’t attack the…things.”

“Demons? Sure you can. They might not die, but you can attack them.”

“I’m a priest now,” Sebastian said.

Aloysius snorted. “You’re supposed to lead the fight against evil, aren’t you?”

“Metaphorically speaking, yes. I’m also not supposed to kill.”

“You went hunting with me when you were a kid. That’s what we’re doing now. Hunting for the Lord, get it?”

Sebastian didn’t say anything. A lack of argument from Sebastian was as good as an Amen as far as Aloysius was concerned.

He rolled back out the serving window. The light was a little better in the main room, and Aloysius could see there were about twenty of the big demons in there, and some damned big machine that was still chugging. It looked like they’d dug a hole under the church that led into blackness so deep that Aloysius decided, then and there, that that was what Hell was like: blackness. At least in the flames of Sunday-school Hell, you could see what the demons were doing to you. He thought the machine must be what they’d used to break open the church like a raw egg.

The demons were climbing up the stairwell, talking in some kind of lingo that he didn’t understand but sounded like orders.

Aloysius skirted the hole toward the office. Maeve howled again, and the chugging of the machine’s motor sped up and started grinding. The church groaned again, and another pew from above slid through the hole and smashed onto the machine.

Sebastian shoved Aloysius aside.

The other end of the pew dropped into the hole, swung around, and smashed into the linoleum where Aloysius had been standing. Meanwhile, the motor spluttered and stopped. Somebody yelled gibberish from inside.

“Watch where you’re standing!” Sebastian yelled.

Aloysius caught himself trying to see the machine better. Sebastian shoved Aloysius again, and they went toward the office.

“Have to hurry,” Sebastian said. “Who knows what they’re doing upstairs.”

Aloysius stopped at the doorway to the office. It was dark, but not dark enough that he couldn’t see what had happened to Maeve.

Sebastian pushed him from behind, and he shoved the boy out of the doorway before he could see anything. Sebastian stumbled and fell down on the floor not two feet from the pit.

“Hey!”

“Sorry,” Aloysius said. Well, the kid was a grown man now, and would have to see what he saw, whether he liked it or not. Aloysius stepped through the office doorway.

Theodore was standing beside Maeve with a revolver out. His hand was shaking so bad that he might have shot Aloysius in the eye, if he’d pulled the trigger.

(He must have brought it with him into church under his suit coat. Couldn’t he just leave his damned guns home for once? But, then again, it was a good thing he hadn’t.)

Maeve had a support beam driven straight through her chest. She shrieked again. Aloysius had no idea how she had the lung power to make such a terrible noise. Weren’t her lungs torn to shreds? How could she possibly suck in enough air around the wood?

“Merciful Jesus,” Sebastian said.

While Aloysius was still standing there, gaping at the wood sticking out of Maeve and wondering just how that worked, Sebastian took the gun away from Theodore, cocked it, and shot Maeve through the eye.

The scream cut out—Aloysius could see her mouth gape loose—but he couldn’t hear a thing, the way his ears were ringing.

Sebastian dropped to his knees, set the gun aside carefully, and started praying over Maeve. Or maybe he was praying that Theodore wouldn’t kill him.

Aloysius picked up the gun and left the office. A demon with the head of a buffalo and about six too many horns was crawling standing by the machine, apparently trying to repair it. Aloysius aimed the revolver at the demon’s back and fired.

The thing bellowed—the sound had a weird whistle to it, the kind of sound you get when you shoot a deer through the lungs, the kind of sound Maeve should have been making—and the thing slid backward into the hole.

Aloysius almost followed it down—what was down there?—but Theodore stopped him. Aloysius offered him the gun, but Theodore shook his head and pointed upstairs.

Aloysius held out a bread knife, but Theodore shook his head again and pulled a curved knife out of his boot.

Aloysius shook his head—what else did the man carry around with him, even at church?—and skirted the hole toward the stairs, which were now so ruined that he had to pull himself up by the handrail part of the way.

The demons were in the church and spilling out of the front, into daylight. Aloysius, near the altar, had to shade his eyes from the brightness. Part of the roof had fallen in, and it looked like a tornado had hit the place. The whole foundation must be cracked.

Aloysius and Theodore ran toward the demons. Aloysius stopped a few yard away, aimed, and fired at the back of the hindmost one. Theodore passed him as the demon fell, grunting. Theodore ran to the back of the next one and swept the knife across its hamstrings. Black blood grouted as the demon tipped forward. Theodore flipped the knife around in his hand and stabbed it into what would have been the kidneys on a human, twisting the knife.

Aloysius spat out bile and aimed again.

Read more at www.WonderlandPress.com

***

Every summer as kids, we would host one group of cousins or another and jump off hay bales, create mazes by crawling the patterns through the tall grass, and steal green apples out of the garden. We also branded calves, killed chickens, and stole steak knives to threaten skunks with. But that’s growing up on a farm for you.

Now I write fantasy, science fiction, and horror—and most of it comes from the worlds that I created as a farm kid, one way or another.

My first novel, Choose Your Doom: Zombie Apocalypse, lets you choose how you’re going to fight a zombie invasion. Warning: you die. Sometimes, you turn into a zombie and then you die. But can you save the world before you kick the bucket? See any major bookstore in order to buy a copy.

“This is how I like my zombies: fast and funny. Choose this book, and you won’t be choosing your doom. You’ll be choosing hours of gooey, gory hilarity.”

- Steve Hockensmith, New York Times best-selling author of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies: Dawn of the Dreadfuls

Website and blog: deannaknippling.com.

Twitter: dknippling

Facebook: facebook.com/deanna.knippling

Smashwords: DeAnna Knippling

***

Images

© Noel Powell | Dreamstime.com

Cover Design DeAnna Knippling

***

Wonderland Press is a publisher of wonderful things by author DeAnna Knippling and her various pen names. I use different pen names so readers of one type of book don’t accidentally buy books they don’t want—for example, I have one pen name that I just use for younger readers.

See the Wonderland Press website for more information on upcoming books, weekly fiction, and limited-time coupons (hint: check on Fridays).

Website and blog: wonderlandpress.com

Twitter: wonderlandpress

Facebook: Wonderland Press

Smashwords: Wonderland Press

***

As always, thanks to my husband Lee and daughter Ray,

without whom none of this would be written.