Chapter 5

Eisenstein and Russian Symbolist culture

An unknown script of October

Yuri Tsivian

This chapter represents yet another attempt at a textual analysis of Eisenstein’s October, a film which has been analysed over and over again at the risk of some sequences being over-interpreted. Nevertheless I have two good reasons for approaching the subject again. One is that almost all analyses of October tend to regard the film as a closed textual entity, with little or no attention being paid to whatever extra-textual connotation a particular sequence might have. Either October is totally impervious to its cultural milieu or we are not prepared to read its text in a broader cultural context. It seems that we are too used to thinking of Eisenstein as a Constructivist artist to admit that some of his constructions might be openended and susceptible to more traditional patterns of contemporary thought. In this respect Eisenstein’s contemporaries were occasionally more acute than modern film historians. In 1928, when the newspaper debates about October were at their peak, Eisenstein was routinely accused of being a ‘Symbolist in film’. Adrian Piotrovsky, Eisenstein’s fiercest critic and one of the most educated men of his time, wrote in an article entitled ‘October Must Be Re-Edited’ about what he called the ‘stylistic discord’ of the film:

When the statues, the crystal and the porcelain begin to fill the screen persistently we are reminded not just of the symbolism of the Tsar’s palace and of autocratic Petersburg that derives from Blok and Bryusov but also of the closely related line of Russian aestheticism that is associated with the World of Art group. Thus, beneath the Constructivist exterior of a materialistically conceived October, there lurk the vestiges of the decadent and outdated styles of our art.1

Historical criticisms like this should not perhaps be discarded as false but rather restated in less accusatory terms to account for the genuinely polystylistic structure of October and, in particular, for those motifs in it that refer back to the literary tradition established by Russian Symbolist writers.

A second reason why I think some well-known sequences from October should be reconsidered is that an unknown early version, which provides us with a significantly different editing concept, has come to light. It is the typescript reproduced here in English translation as an appendix to this chapter. The typescript, of which only the last part survives, obviously represents the last script version of October. It differs not only from the screen version but also from the literary treatment published in the six-volume Russian Eisenstein edition.2 This latter version was not meant to be used during the actual shooting, despite the numbering of the lines, but to be read by other people: after all, the Party’s Anniversary Committee did exercise tight control over the production. The script in the appendix is, by contrast, a working script. Its lines look more like mnemonic signs than narrative sentences. Often in the script Eisenstein uses actors’ names instead of the names of characters and this indicates that he is referring to sequences that had already been cast and shot. Lines such as 330 (‘326 again’) confirm that we are dealing with an editing script. To judge by the physical condition of the typescript, it has already been worked with. It therefore seems plausible that a version of October existed which is quite different from the ones that we know, and the script in question is a kind of shorthand version of it. There is only one time when this version could have been made. As we know, Eisenstein was unable to complete the editing in time for the celebration at the Bolshoi Theatre of the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution so that only some fragments of the film were shown on 7 November 1927. After this screening Eisenstein was advised to change the montage conception, to re-edit the fragments and to shorten the whole film. At the same time he insisted on several days’ additional shooting and this request was granted. It seems that this editing script was produced for the Bolshoi screening, the storming of the Winter Palace being one of the fragments shown on that day.

We are therefore dealing not just with a different montage version of October (familiar shots in unfamiliar cutting positions, script lines referring to unknown footage—all this would in itself provide enough material for a comparative study) but also with a version that pre-dates any of the screen versions, a fact which allows us to trace the genesis of each shot. Although the script requires more extensive textual analysis, I am going to touch only upon the points that link October to Russian Symbolist culture.

THE CASE OF THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT

Let us consider script lines 428 to 431 in the appendix. The scene is the mortuary in the Winter Palace, omitted from the final version of October, although photographs from the Eisenstein Archive in Moscow displayed in the ‘Eisenstein: His Life and Work’ exhibition testify to the fact that the mortuary sequence was shot.

Why a mortuary? If we compare this editing script with the literary version and also with the screen version, we find that Eisenstein hesitated to the very last moment as to how he should treat the Provisional Government. Each different version provides a different solution. In the editing script under discussion line 431 reads ‘Torpid government’. In the literary treatment we find a slightly different epithet: ‘Petrified government.’3 The difference is not as negligible as it might appear. Eisenstein was very particular about the exact wording of script lines: suffice it to recall his classroom analysis of the distinctly different treatments required by the apparently synonymous script lines ‘Dark window’ and ‘Unlit window’.4 The ‘petrification’ of the Provisional Government looks a particularly apt remark for October because it fits perfectly into Eisenstein’s general design of stone images in the film and seems to anticipate the observation made by Marie-Claude Ropars-Wuilleumier that the statues in October represent forces hostile to the Revolution.5 What is more, the remark is reminiscent of Symbolist theatre, and in particular of Alexander Blok’s play The King in the Square, written soon after, and under the impact of, the revolution of 1905. The coup de théâtre in Blok’s play lies in the fact that the King, who is permanently present on stage (the other characters keep addressing him in the hope of getting an answer), turns out towards the end of the play to be a stone idol. Let me quote Blok’s stage direction for the concluding scene:

At that very moment the infuriated crowd pours out on to the steps behind the Poet. The columns shatter from below. Wailing and shouting. The terrace caves in, taking the King with it. …In the red glow of the torches you can clearly see people down below scouring around searching for bodies, holding up a stone splinter of a cloak, a stone fragment of a torso, a stone hand. You can hear cries of horror: ‘The statue! The stone idol! Where’s the King?’6

The opening sequence of October with the Tsar’s monument being dismantled overtly alludes to this dénouement and both destruction scenes function within a more general inter-textual matrix, that of Pushkin’s The Stone Guest, to which Eisenstein refers by making his statue nod before it falls.

This reference to Blok makes it easier to discern the outline of what appears to be Eisenstein’s initial conception of the film in the literary treatment. By making October begin precisely where Blok’s play ends and by inserting later the line ‘Petrified government’, Eisenstein seems to reaffirm the essentially Symbolist idea of history as a permanently alternating cycle between the petrification and destruction of power. Although this idea does not exactly pervade the overall structure of October, some sequences (such as the Kerensky-Napoleon metaphor) still bear the traces of Eisenstein’s initial intention to turn the Provisional Government into statues. Curiously this cycle is worked out more explicitly in The General Line, when plaster busts of Lenin threaten to substitute for revolutionary power.7

For some reason the line ‘Petrified government’ was discarded and replaced by ‘Torpid government’ in the editing script. Instead of transforming the image, Eisenstein now worked on it through its context. This is where the mortuary comes in. Lines 428 to 430 mention rows of corpses with numbers on their heels. Then Eisenstein abruptly cuts away to the shot of the Provisional Government (line 431), which this time is described as ‘torpid’. The cut-in metaphor is quite obvious and like the one that Eisenstein had already employed in The Strike. The meaning here was probably related to the verbal cliché ‘political corpse’, which was current in newspapers of the time. It is small wonder that Eisenstein abandoned that as well.

The final version represents a return to some elements of the initial design. At one moment the audience sees empty suits on the screen instead of the Provisional Government.

As we can see, the metaphor has changed its locus and is back in the frame, instead of being on the cut. Once more a transformation is implied, this time disappearance rather than petrification.8 Finally, this sequence also borrows from the vocabulary of the Symbolist theatre, the empty suit metaphor finding its extra-textual counterpart in The Fairground Booth, an earlier play by Blok staged by Meyerhold in 1906. In this play a trick somewhat similar to the petrification scene in The King in the Square was introduced. A council of mystics was permanently on stage watching the show. The moment the show takes an unpredictable turn, the mystics suddenly lose their identity:

Harlequin took Columbine by the hand. She smiled at him. General collapse of mood. Everyone lifeless on the edge of their chairs. Coat sleeves stretched out and covered the hands as if the hands did not exist. Heads disappeared into collars. It was as if empty coats were hanging on the chairs.9

Eisenstein never saw Meyerhold’s famous production of the play but for Meyerhold’s disciples and for an entire generation of non-traditional theatre people The Fairground Booth was, as it were, a cult production and it was recalled over and over again in minutest detail by those who had seen it. That accounts for the reproduction of its key metaphor in October. In his memoirs Eisenstein recalls a session like this when a former participant in the production reminisced to Meyerhold’s students:

Nelidov, of the young idealists. Nelidov participated in the production of The Fairground Booth. And The Fairground Booth was to us as the Church of Spas Neriditsa was to ancient Russia.

In the evenings Nelidov would talk about the wonderful evenings of The Fairground Booth, about the conference of mystics who look at us now from Sapunov’s sketches in the Tretiakov Gallery, about the première, and about how Meyerhold, as the white Pierrot, stood like a stork with one leg behind the other and played on a thin reed pipe.10

The impression left by these stories was so strong that Eisenstein chose to use the empty suit metaphor from The Fairground Booth to describe his first meeting with its celebrated producer. This meeting took place in 1914 in St Petersburg when the 16-year-old Eisenstein attended a public lecture given by Konstantin Miklashevsky, a theatre historian who was later to become an émigré film-maker and the real author of the script for Feyder’s film La Kermesse héroïque. Meyerhold was also there, sitting on the stage among the honoured guests. Twenty-nine years later Eisenstein took the trouble to recall the lecture:

The chairman’s table was in the depths of the stage, dignified, like the mystics at the start of The Fairground Booth, but I remember and see only one of those seated at it. The others have vanished into the slits of their own cardboard busts, disappeared in memory, as those in The Fairground Booth disappeared.

The only one—you have guessed it—the divine! The incomparable! Mey-er-hold.

It was the first time I had seen him. And I was to worship him all my life.11

If we agree that, inter-textually, eye-witness accounts may be at least as influential as seeing with one’s own eyes, the empty suit metaphor in October may be regarded as an attempt to recreate on film the impression that Eisenstein had missed twenty years earlier as a theatre-goer. The idea of early impressions being reproduced in his later films was among Eisenstein’s favourite themes when discussing his own work: suffice it to recall October and the ‘forbidden’ passages from Zola, or the Teutonic knights from Alexander Nevsky and the anecdote about Eisenstein’s mother’s nasty habit of frightening her son by motionless grimaces. If Eisenstein’s predilection for Symbolist imagery needs any psychological motivation at all, it may be traced back to two figures Eisenstein regarded as ‘incomparable’ and ‘divine’ from his early days and for the rest of his life: Vsevolod Meyerhold from Symbolist theatre and Andrei Bely from Symbolist prose.12

THE ‘INTELLECTUAL’ TOPOGRAPHY OF THE TSARINA’S BED-CHAMBER

The rest of the discussion will be confined to the scene introduced by the intertitle ‘The Tsarina’s bed-chamber’. When we compare two versions of the scene, the first thing that strikes us is the considerable divergence between the editing patterns. The editing script version (lines 365–422) looks less ‘intellectual’ (in the specifically Eisensteinian sense of the term) and more diegetic. This suggests that the ‘intellectual’ sequences in the film are due mainly to a later re-editing when it was decided to release October as one film instead of two. If we examine the chase in the Tsarina’s bed-chamber from the continuity point of view, we see that the only continuity conditions that are strictly observed in the screen version are correct matches on movement, whereas constant eye-line mismatches and directional mismatches make the space of the bed-chamber vague and indetermi-nate.13 Sometimes we cannot even tell for sure how many characters are participating in the chase: some cuts seem quite continuous because of a good match on movement, despite the fact that two different characters are made to pass as one.

From what we can tell from the script version, this editing style was not something carefully planned in advance. It seems that the occasional ‘trick cuts’, which are meant to make the sequence look more or less coherent at the expense of its diegetic clarity, are a kind of emergency device Eisenstein used to cope with excessive footage. This becomes quite evident when we look at the editing script. In it the chase was supposed to be an extended event taking place in several rooms in succession: the bed-chamber (lines 366–8 inclusive), the prayer-room (369–72 inclusive), two lavatories—one semi-circular (387), the other right-angled (388), the linenroom (379–94) and the trunk-room (395–422), which is not named directly in the script but is referred to in other documents. The six rooms were meant to form a realistically motivated space, a space that directly corresponded to the pro-filmic interior architecture of the royal bed-chamber (which was in fact a whole apartment rather than a bed-chamber) in the Winter Palace. There were to be no inconsistencies like the lavatory pan in the bed-chamber, which the audience is forced to believe in when watching the screen version where a mere turn of the sailor’s head creates a spatial contrast as scandalous as those in Un Chien andalou by linking objects which simply cannot coexist in one room, like icons and a bidet.

When we maintain that no such spatial inconsistencies exist in the editing script version, this does not mean that the editing is less conceptual there. The real difference is that the editing script version is more deeply rooted in the diegesis. When Eisenstein wanted to confront the world of religious objects and the world of human biology, what he tried first was something any run-of-the-mill film director would think of: in the editing script version the women soldiers hiding in the prayer room exchange fire with the sailors hiding in the lavatory (lines 371–6). Script lines 381–6, which describe the sailor looking around him, show that the conceptual juxtaposition of objects is already all there, except that spatial boundaries are not violated. Toilet requisites, meaning towels or toilet paper (line 384), look perfectly natural in a linen storage room, but Eisenstein still thinks it necessary to insert an orientation mark—‘Opens a door: a lavatory’ (lines 387–8) to enable him to cut in a lavatory pan. That is where the fine distinction between conceptual and intellectual montage lies: in later versions all the openings of doors are omitted. There is no prayer room and no lavatory in the screen version. What we have instead is a single formless room which is called The Tsarina’s bed-chamber’ but which looks more like a junk shop than a royal parlour.14

What should be emphasised once again is that what we see in the editing script and what we see in the final screen version are different stylistic layers, the second layer arising from the need to compress the first. ‘Intellectual montage’ was born from the attempt to cover the action at a very rapid pace, rather as a digest does. In order to do this, Eisenstein had to strip the diegetic space of many of the orientation marks required for the continuity editing and to ‘replace’ them with differentiating features he called ‘intellectual’.

In a sense it was an innovation forced on him by circumstances, by the situation that Viktor Shklovsky thought was the main impulse for the early history of Soviet cinema. Shklovsky was fond of repeating anecdotes about Kuleshov’s short-shot cutting being invented because no full-length film stock was available at the time so that cameras had to be loaded with old laboratory offcuts. Another of his stories rings more true. Because of the same problem Sanin’s Polikushka was shot on old pre-revolutionary stock which had long been out of use because of its so-called ‘haze’, a finely meshed web of cracks in the emulsion. This haze made European audiences enthuse over what they thought was highly sophisticated soft-focus photography!15

When he strung together a sequence according to the ‘intellectual’ principle, Eisenstein was operating with the debris of the coherent diegesis he himself had observed while shooting and editing the first version. This means, as far as textual analysis is concerned, that sequences like this in October should be analysed with caution, layer by layer. It would be useful to try to reconstruct the initial diegetic situation which a particular shot was primarily conceived as part of. Contrary to what we might expect, the ‘intellectualisation’ of editing patterns was a double-edged sword: brought too close to the foreground, the symbolic connotation of some objects threatened to become practically unreadable. To understand why they are there at all one should try to build them back into the context that they have lost. This may be illustrated by the case of the china eggs, an image whose semantic potential was gradually reduced to the point where it vanished altogether.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE EGG SYMBOL

When Eisenstein and his team were first shown into the Tsarina’s bed-chamber they were stunned by the sight of huge painted eggs made of china. There is an entry in Eisenstein’s shooting diary for 14 April 1927: ‘The bed-chamber alone contains 300 icons and 200 china Easter eggs. It dazzles you. A bed-chamber that psychologically a contemporary could not stand. It is intolerable.’16 If we compare the number of lines devoted to eggs in the editing script version with the number of egg shots in the screen version, we see that the ratio is eight to two, or even eight to one, since the two shots are ‘concertinaed’ into what amounts to a single cutting position. In the sonorised version re-edited by Alexandrov the egg shots were cut out altogether, probably because, thirty years after the film was made, Alexandrov was uncertain of what the egg image was meant to signify. We have to trace the history of the egg sequence back to the editing script in order to restore its meaning.

Script line 382 reads ‘Icons. Eggs. Crosses’. It corresponds to a series of similar shots in the film. We recall that these shots mark the beginning of the sequence illustrating the sailor’s inner monologue while he is examining the details of the royal bed-chamber. The sequence is edited according to an apparently simple pattern. Religious objects are juxtaposed to objects that remind us of human genitals: a bidet, a lavatory, and so on. Eggs as a symbol for Easter belong to the religious sequence.

Two script lines have no counterpart in the screen version:

414 The sailor with the St Nicholas egg in his hand.

418 Nicholas II’s eggs roll.

What is intended here is a double pun. First, there is a play on the homonym of the Tsar’s name and that of his patron saint. Second, the Russian word for eggs, yaitsa, has a double meaning. The second meaning is a contemporary colloquialism for testicles, so that a more apt translation of line 418 would be ‘Nicholas II’s balls roll’. The pun makes the egg image not the fixed image it appears to be earlier in the script but a cluster of two meanings that are crucial to the sequence: eggs stand both for religious objects and for male genitals, representing the two extremes which were believed to determine the politics of the last Russian Tsarina, her frantic sexuality and her fanatic religiosity (cf. the popular image of Rasputin as a saint and a sex-machine at the same time).

Lines 416–46 link the theme of genitals with the theme of the Revolution. In his recent study François Albera has demonstrated how Eisenstein built into October two early impressions from his childhood: the scene from Zola’s Germinal in which revolutionary women march brandishing the genitals of their castrated oppressor; and Marie-Antoinette’s head impaled on a soldier’s pike, which shook the young Eisenstein when he saw it in a waxworks.17 Albera’s study is well grounded in Eisenstein’s own post-analyses and he is quite right when he states that for Eisenstein the very essence of the Revolution was symbolised by the decapitation/castration of the ruler.18 It is in this context that the script lines that deal with Nicholas’s rolling balls (418, 422) or the scene in which the same eggs/balls are stolen by a woman from the Tsarina’s bed-chamber (line 446) should be situated.

The egg image also figures in the sequence in lines 401–14. Let us take a closer look at what is happening in this sequence. It is a short episode absent from the final version of October. Some cadets are trying to disarm a revolutionary sailor but the sailor tricks them into dropping their guns. This apparently straightforward little narrative is constructed so as to convey a double meaning and the very technique of its narrative construction bears a strong resemblance to what Russian Symbolist writers did in their prose and plays.

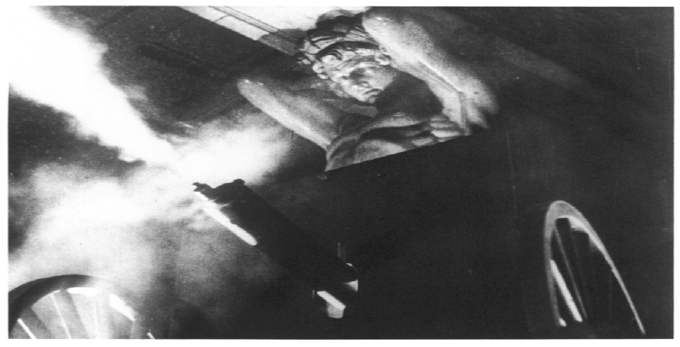

Because of a defect in the typescript line 403 is partly illegible: we cannot therefore know what the sailor is groping for. The next time we see him (line 405) he is about to throw whatever it was that he was groping for in line 403. Then we see him standing in a whirl of feathers with a bomb (line 410), the disturbance being caused by the salvo from the Avrora (line 406). The next time we see him the object he has in his hand is not a bomb but an egg (line 414). If we assume that the defective line 403 reads something like ‘The sailor jumps aside and gropes for a china egg behind him’ the story becomes fairly connected: the sailor threatens his enemies with a make-believe bomb which is actually an egg; the salvo comes in time to play the part of an explosion; the cadets drop their rifles. This would be the outcome if you were programmed to read the sequence horizontally. But this kind of reading would not seem natural to anyone raised on Russian Symbolist culture. For a Symbolist, and for any of his readers, a text is a puzzle to be read both across and down. You do not read Andrei Bely’s Petersburg to learn how a young man tried to blow up his father with a bomb. The typical reader of this novel looks for vertical correspondences, such as why the bomb is repeatedly linked to the hero’s chronic flatulence on the one hand, and to tinned sardines on the other. These are the substitutions through which a Symbolist writer is expected to communicate his ‘timeless message’. Eisenstein, in his effort to make objects mean more than they do mean, draws much of his narrative technique from Symbolism. With his usual insight Osip Brik noted this as far back as 1928: ’[Eisenstein] takes the principle of the creative transformation of raw material to the point of absurdity. In their time the Symbolists in literature and the “Non-Objective” painters did the same and this work was a historical necessity.’19 Among the ‘vertical’ substitutions inviting the audience to read the sailor story from the editing script in a Symbolist way (the salvo from the Avrora substitutes for the bomb blast, the feathers imitate an explosion) the egg-bomb substitution is especially significant. Performed at the diegetic level, it parallels another substitution functioning at the level of discourse, namely the cut that Eisenstein has commented upon in his Film Form.

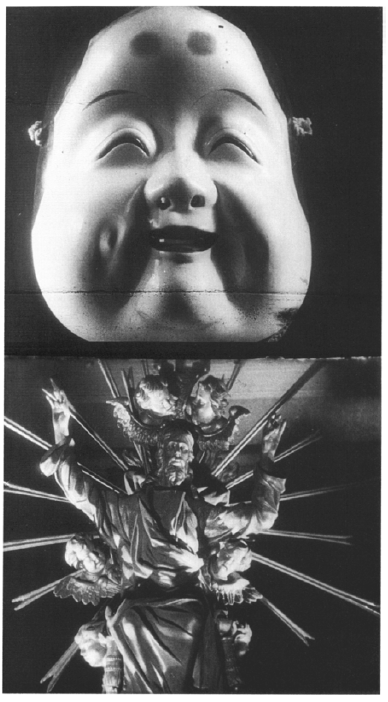

Eisenstein used this cut from October to illustrate his idea of ‘graphic conflict’ (two objects juxtaposed generate an idea or an ‘image’ that is external to both). He insisted that the star-like Baroque Christ figure produced the effect of a bomb burst.20 To make sure that the trick works Eisenstein repeats the cut several times in succession.

The egg simile seems quite clear, an egg being a graphic equivalent of all that is perfectly self-contained. Then why not use an egg as the first element of the cut? It seems that neither of the elements forming the ‘graphic conflict’ is fortuitously chosen here. Just imagine an egg instead of the oriental mask and, say, a starfish instead of the Christ figure and you will have a Ballet mécanique instead of October. To anyone acquainted with Symbolist imagery the image of an exploding oriental head has a familiar ring. The symbol of a human skull filled with dynamite is one of the early literary metaphors for revolution. Implicitly it goes back to Dostoyevsky’s idea of revolution as madness, a malady of the brain. The idea was developed by Andrei Bely in his Petersburg, a novel about the 1905 Revolution, where it figures as the hero’s fixation. Probably, as Roman Timenchik has recently observed, Dostoyevsky’s idea had to travel via England in order to acquire the form of an exploding head. Let me quote an anarchist speech from G.K.Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, the novel which was translated into Russian before Bely began work on his Petersburg:

Dynamite is not only our best tool, but our best method. It is as perfect a symbol of us as incense of the prayers of the Christians. It expands; it only destroys because it broadens. ‘A man’s brain is a bomb,’ he cried out, loosening suddenly his strange passion and striking his own skull with violence. ‘My brain feels like a bomb, night and day. It must expand! A man’s brain must expand, if it breaks up the universe.’21

In an article written in 1918 Bely provided a similar commentary on his Petersburg:

Our freedom dares us to fly up over the fire of our heart to the limits of the skull and to rupture those limits. Nikolai Apollonovich senses within himself the need for that rupture, like a bomb inside him, but he has no desire for it…. The skull will be smashed: the bright Dove of Advent will descend into the orifice of our own ruptures.22

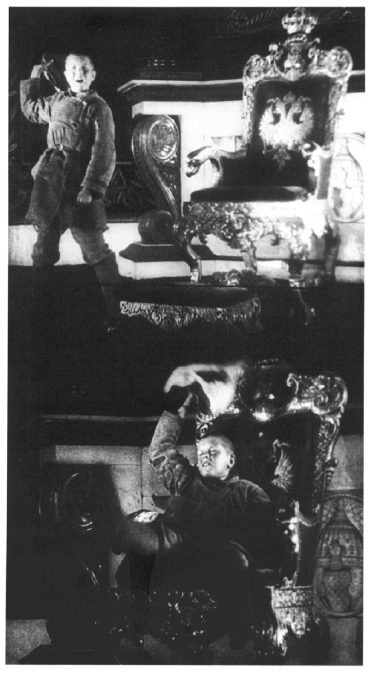

Buddhism vs Christianity; stasis vs ecstasy; fatalism vs mutiny; stagnation vs explosion—these oppositions equally dear to Russian Symbolist thought and to Eisenstein as a philosopher of art (especially in his Non-Indifferent Nature period) cluster round the cut where the Japanese mask of the goddess Uzume explodes into the image of Christ. It seems that the egg/bomb substitution in the sailor story relies upon a very similar set of ideas. Structurally the sequence is built round the salvo from the Avrora, the pivotal point of the uprising. Semantically it centres round the idea of explosion. The egg/bomb correlation connects violence with procreation, a coalescence that is quite natural for a film that is an apologia for the Revolution. A shot of a peasant boy rejoicing on the Tsar’s throne, which marks the climax of the screen version of this sequence, comes in the editing script version immediately after the burst of feathers, suggesting, in a somewhat Méliés-like fashion, that the boy emerges from the explosion. In the screen version the idea of revolution as explosion is reinforced at the discursive level by the famous jump-cut ‘boy by the throne/boy on the throne’.

By violating the rules of continuity editing Eisenstein intended to take this moment out of ordinary, serial, experientially-motivated time. Diegetically the idea of marking historical moments and projecting them, as it were, into eternity is expressed in October by the obsessive use of clocks. In the passage from script to screen we can clearly see how the mechanism of intellectual cinema is made to work. In order to define the moment of revolution (burst, leap) as opposed to evolution (gradual, eventless development) Eisenstein dropped the diegetic symbolism of the exploding egg and proposed its discursive equivalent, a jump-cut.

EISENTSTEINIAN BAWDINESS

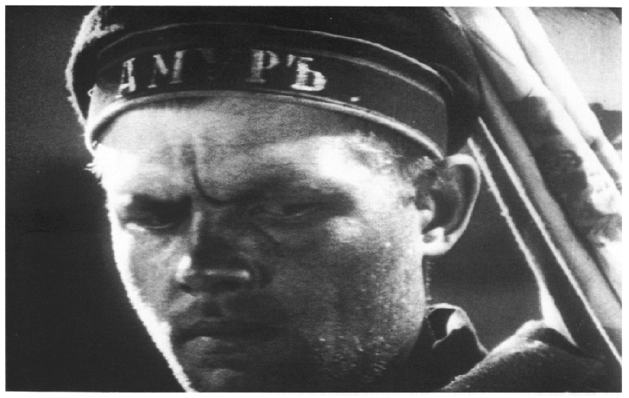

In his analysis of October David Bordwell has illustrated how important paronomasia (or punning) is to the understanding of what a particular sequence means.23 The eggs/balls semantic shift demonstrates that this is also true of the sequence in the Tsarina’s bed-chamber. The apparently simple pattern of the sailor’s inner monologue while he is examining the bed-chamber turns out to be not quite as simple when we apply verbal codes to decipher it. The very first shot of this little scene bears an inscription within the shot that is open to a double reading.

The word ‘Amur’ on the sailor’s hat is historically correct because there were sailors from the warship Amur among those who stormed the Winter Palace. But it still looks like a pun. Apart from the inevitable Francophone associations, to a Russian ear it means:

- a river in Siberia;

- the warship bearing that name;

- Eros (or Cupid), the armed god of love.

The last meaning may pass unnoticed in the screen version but not in the editing script version, where it was substantiated by a number of other shots. We know from his drawings how fond Eisenstein was of visual puns on weapons and sex. A frame from an earlier reel of October may serve as a reminder that in this film erotic metaphors were also used to signal some points in the historical narrative.

It may be that the sailor inspecting the Tsarina’s bed-chamber was also initially conceived as a mythological figure of an armed lover. There is a line in the script that is missing from the film: the sailor looks at a bidet and then, disgusted, he wipes his bayonet (line 393). As François Albera has demonstrated, a similar metaphor of a bayonet (in close-up) ripping a pillow (intercut with two women soldiers gasping) still exists in some versions of October, indicating that at its metaphorical level the sequence in the Tsarina’s bed-chamber implies the notion of rape. The very fact that in other versions this close-up has been omitted is eloquent testimony to the fact that for some censors the implication has been too transparent. Another missing line (400) maintains the metaphor: after the sailor has discovered the women in one of the trunks we are shown pieces of linen flying through the air and then the sailor saying ‘Ugh!’ and lighting a cigarette in what must be understood as a post-coital gesture.

We might ask why Eisenstein was so insistent on making this point. The question is not that simple, particularly as, immediately after the Winter Palace was seized, persistent rumours circulated that acts of rape and violence had taken place during the assault. Was Eisenstein implying that the rumours were well-founded? After all, Kerensky did summon the Women’s Shock Battalion to defend the Palace and the mutinous sailors who led the attack could not exactly be called the most disciplined element of the Revolution.

In order to resolve this question we need to pose a more general question about Eisenstein’s attitude towards historical accuracy. Some of his contemporaries, especially those who belonged to LEF, criticised October for its lack of historical authenticity. Sergei Tretyakov wrote in his review that in the film the ragged sailors of 1917 looked as smart as the naval officers and concluded: ‘If he is familiar from his own experience with the epoch depicted on the screen, the viewer will be divided between his own memory and the directive from the screen.’24 Let me quote another review, this time by Osip Brik:

Everyone knows that the battle for the wine-cellars after the Revolution was one of the murkier episodes of October and that the sailors not merely did not smash the cellars but tried to drink them up and refused to shoot the people who had come to take the wine…. But when a real sailor efficiently smashes real bottles the result is not a symbol or a poster but a lie.25

Tretyakov and Brik, both adherents of the LEF doctrine of the ‘literature of fact’, imply that Eisenstein tries to replace real history by political mythology. The reproach is not totally unfounded, but this explanation does not account for all the deviations from actual facts that we can detect in October. It would be more correct to say that what Eisenstein particularly favoured was not exactly political but rather popular mythology, a system of rumours and common talk that spread like wildfire immediately after the October Revolution. It is not a question of incompetence: firsthand information in the form of memoirs written specially for the occasion was at Eisenstein’s disposal before the shooting started. Kerensky’s flight from Gatchina serves as a good example. In John Reed’s book Ten Days That Shook the World (October was first conceived as a screen version of the book but the idea was discarded and the book itself soon forbidden because there was too much of Trotsky in it) Kerensky’s flight was described as being a success because Kerensky was disguised as a sailor. The story is perfectly true and is based on the evidence of the man who came to arrest him. But what Eisenstein was going to use instead was an apocryphal story according to which Kerensky fled disguised as a nun. In his literary treatment Eisenstein commented: ‘Bonaparte in a skirt’.26 Eisenstein needed the false story because it was better suited to what he had in mind at the metaphorical level: first, the Kerensky-Napoleon simile—the famous sequence of the ‘two Napoleons’; next, the ambiguous sexual status Eisenstein had already ascribed to Kerensky with the intertitle ‘Alexander Fedorovich in the Apartments of Alexandra Fedorovna’ (an imputation that can easily be refuted since in reality Kerensky lived in the apartments of Alexander III).27

The rape story is of a similar kind. The Press of the day was full of rumours that the women defenders of the Winter Palace had been raped by the attacking crowd: we also read about it in Chapter 5 of Reed’s book. The City Council ordered an immediate investigation into the allegations. It was to be supervised by the Mayor, Schreider, a man of stern democratic principles and great personal courage. On the night of the storming of the Winter Palace, followed by a group of unarmed civilians, he had tried to stop the revolutionary crowd and save the Provisional Government: Eisenstein caricatured him in the sequence where the old man confronts the bridge patrol. The enquiry found that the newspaper scare story was totally unfounded. When they were summoned to the public hearing, the women soldiers testified that no harm had been done to them, except that all 136 of them had been disarmed and sent back to the Pavlov barracks. Nonetheless, as in the case of Kerensky’s disguise, Eisenstein preferred the popular legend to the true story, even though the former might seem detrimental to the character of the victorious power. He did this for the sake of the all-embracing metaphor that underlies every key sequence in October, the Revolution portrayed in terms of erotic conquest.

Curiously, popular mythology and the actual historical setting of October 1917 provided Eisenstein with a set of coincidental details to play upon: the Winter Palace defended by women against the virile force of the revolutionaries was, by virtue of accidental irony, counterbalanced by the fact that the Smolny Institute, the headquarters of the revolutionaries and the base for the attack, was known as a former school for fashionable young ladies of the nobility. The mutual travesty of opposing palaces did not escape the Press of the day: a photograph appeared showing Trotsky’s (later Lenin’s) room in the Smolny flanked by two Red Guards with a sign on its door reading ‘School-Marm’. All this constituted the popular mythology of the Revolution reflected in common talk, cartoons and the topical satire of the daily press and echoed later in Eisenstein’s October. Here the Winter Palace was further travestied by making Kerensky an effeminate character: the famous sign ‘School-Marm’ was also used to decorate the door of the Menshevik faction. We can go even further and assume that for Eisenstein the architectural body of the Winter Palace was itself a huge metaphor for femininity. The idea might not seem too far-fetched if we remember that Eisenstein was an attentive reader of Otto Rank’s psychoanalytical works, and also that in popular consciousness the last twenty years of the Romanov dynasty bore all the signs of ‘petticoat rule’. In this case it is no wonder that the climax of the film is signified by, of all places, the Tsarina’s bed-chamber. To crown the gag, it should be added that the corridor through which the revolutionary crowd penetrated the Winter Palace, now called the October Corridor, was then known as ‘Her Majesty’s Personal Entrance’.

The extent to which the Winter Palace is conceived as an important character in the film may be illustrated by the famous sequence with Kerensky and the peacock. The sequence intercuts Kerensky entering the royal apartments with a clockwork peacock turning. Usually the peacock shots are interpreted as non-diegetic inserts providing a simile for Kerensky’s arrogance. This reading is obviously too simple. Noël Burch once remarked that the movement of the peacock

is so tightly meshed into the movement of the door itself that it resists any reduction to a single signifying function. A naive reading, predicated on the inviolability of diegitic space/time, might conclude that this is an automaton set in motion by machinery which connnects it with the door.28

We should ask: what was the reading envisaged by Eisenstein? To find out, we need to look more closely at the sequence. Kerensky pauses in front of the door; the peacock turns its back on the audience and opens its tail; Kerensky opens the door and enters; the peacock turns ‘about face’ again so that it is now facing the audience; then we see a padlock in closeup. None of the readings that pursue the Kerensky-peacock simile can account for the padlock, which seems to have no function in either diegetic or contextual terms. What Eisenstein had in mind was not so much to provide a simile for Kerensky himself as for the Winter Palace that the new Prime Minister was moving into. Eisenstein’s idea for this sequence was not to ignore diegetic space but to construct an ‘imaginary space’, much in the spirit of Kuleshov’s experiments. By operating through the dynamics of movement and by trying to manipulate different shot scales so that the audience is forced to believe that the peacock in close-up is much bigger than Kerensky in full shot (an assumption that did not work in practice), Eisenstein was hoping to achieve the effect of Kerensky entering the peacock’s arsehole. The idea did not quite work out, not only because shot scales were too resistant to be manipulated in this way, but also because the action is too slow. If you try to project the sequence on the editing table using the rewind speed of over thirty-six frames per second, you suddenly witness Eisenstein’s design coming to life. Kerensky is ‘devoured’ by the peacock through its arsehole, on which a padlock is then ‘suspended’. The Winter Palace has entrapped its Prime Minister.

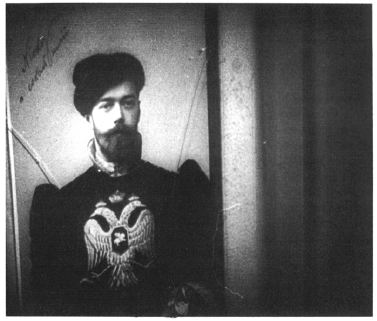

Let us return to the sailor’s inner monologue in the Tsarina’s bed-chamber: one more verbal pun seems to need a commentary. There is a shot reproducing a photograph of Nicholas II in close-up, his head slightly off-centre so that the viewer can decipher an inscription on it.

The inscription reads ‘Nicky the falconer’ and is immediately followed by a shot of a chamber-pot. This juxtaposition is affirmed with the insistence that is characteristic of Eisenstein when he is determined to drive his point home. The cut is repeated three times with the only difference that the photograph is now shown in full.

The joke implied by the first cut lies in the juxtaposition of the idea of duck-hunting with falcons—the favourite outdoor entertainment of the Russian Tsars dating back to Ivan the Terrible—and a special type of chamber-pot that is shaped like a duck and is also called a duck (utka) in Russian. When the cut is repeated the second time the verbal pun turns into a visual one: the royal eagle on the Tsar’s hunting outfit enters into an interplay with the hygienic ‘duck’, bringing the two notions into what Eisenstein used to term a ‘conflict’ of high and low on an axiological as well as a plainly spatial scale.

We should not be too tempted to interpret Eisenstein’s puns psychoanalytically. All that is going on in the Tsarina’s bed-chamber has very clear cultural origins. Jokes about the Tsar and his chamber-pot were already encoded in the Russian euphemism kuda tsar’ peshkom khodil ‘to go where the Tsar went on foot’ and belong to the old Russian tradition of what we might call ‘royal bawdry’. This was particularly popular with the leftist theatre of the 1920s: the Emperor on his chamber-pot in Meyerhold’s Earth Rampant and similar scenes in Eisenstein’s Wise Man and in Igor Terentiev’s The Government Inspector.29 When in November 1917 Larisa Reisner, the famous woman commissar, went on a tour of inspection of the Winter Palace, she could not resist the temptation to make a joke about Kerensky being thrown off ‘if not the throne then the stool of Nicholas II’.30 All this, including the sequence in the Tsarina’s bed-chamber from October, seems to stem from a real event in Russian history, when Catherine the Great was found dead in her private lavatory. The event was immortalised by Pushkin in a poem:

The dear old lady lived,

Pleasantly and somewhat prodigally,

She was Voltaire’s first friend,

Gave orders, burned fleets

And died, sitting on her bed-pan.31

The joke is based upon a pun on the Russian word sudno, which means both a ship and a bed-pan, the two notions also being juxtaposed in Eisenstein’s October in the sequence where the revolutionary sailor examines the Tsarina’s bed-chamber.

Finally, the very idea of a character’s inner monologue based on a network of puns comes from Symbolist prose. Eisenstein himself defined this method in the following way: ‘The elements of the historiette itself are thus chiefly those which, in the form of puns, provide the impulse towards abstraction and generalisation (mechanical spring-boards for patterns of dialectical attitudes towards events).’32 Eisenstein and his later commentators justly link this technique to James Joyce. Contemplating his famous project for a screen version of Marx’s Capital, Eisenstein wrote, ‘Joyce may be helpful for my purpose: from a bowl of soup to the British vessels sunk by England’.33 Nevertheless Joyce’s influence can hardly be relevant to October: according to all the evidence, Eisenstein read Ulysses in March 1928. It seems that Joyce’s impact on Eisenstein was as great as it was because the ground had already been prepared. The stringing together of sequences according to free verbal association can be found in Bely’s Petersburg as well as in Ulysses. Let us take the example of the bowl of soup: it may seem Joycean, but Eisenstein’s method of working with the technique of inner monologue looks very close to Bely. Even some details coincide: in Petersburg there is an episode where the hero is sitting over his plate of soup trying to find a topic of conversation. His mind wanders, its starting point being the sight of pepper in the soup:

And in his loving son’s head senseless associations began whirling about.

‘Perception…’

‘Apperception…’

‘Pepper…not pepper but a term…terminology…’

‘Logy…logic…

And out whirled:

‘Cohen’s theory of logic…’.34

Eisenstein’s ‘intellectual montage’ works in the same direction from everyday trivia ‘towards abstraction and generalisation’:

Throughout the entire picture the wife cooks soup for her returning husband…. In the third part (for instance), association moves from the pepper with which she seasons food. Pepper. Cayenne. Devil’s Island. Dreyfus. French chauvinism. Figaro in Krupp’s hands. War. Ships sunk in the port. (Obviously not in such quantity!!) N.B. Good in its non-banality—transition: pepper—Dreyfus—Figaro.35

In the early 1930s Eisenstein had a conversation with Bely on which he reports in an unpublished part of his memoirs.36 When asked about Joyce, Bely admitted to never having heard of him. The most curious thing about this is not Bely’s confession but Eisenstein’s sense of surprise at hearing it. It demonstrates the extent to which the literary technique of Bely and Joyce was experienced by Eisenstein as a joint impulse towards the revision of the narrative technique of the film medium.

MESSAGE AND VOCABULARY

All present-day research on Eisenstein, as well as the press controversy about him immediately after October was released, seems to develop in two directions. Some studies concentrate on him in the context of the Constructivist endeavours of Russian and European art in the 1920s: this approach is more characteristic of the French school of textual analysis. Others investigate Eisenstein in the context of more traditional culture and discover that his work fits there perfectly as well. As Susan Sontag has written: ‘Eisenstein, who saw himself in the tradition of Wagner and the Gesamtkunstwerk and in his writings quotes copiously from the French Symbolists, was the greatest exponent of Symbolist aesthetics in cinema.’37 The question may arise—and it did actually arise after this paper was presented at the Oxford Conference—as to which approach is more relevant, or, to put it more bluntly, as to what Eisenstein really was: an avant-garde film-maker or a traditionalist? This question has no single answer that is equally valid, say, for The Strike and Ivan the Terrible. In the case of October it is useful to distinguish between its image vocabulary and its message. You can control your message but it is more difficult to control your vocabulary, which is something you absorb from your cultural milieu before you are capable of criticising it. The October Revolution was not the first Russian revolution but the third, the first being the revolution of 1905. In 1905 the Russian literary scene was dominated by the Symbolists and it was they who established the basic symbolic vocabulary for this and for any subsequent revolution. Eisenstein was not a Symbolist as far as his message was concerned, but he used Symbolist vocabulary to formulate his message. His films are largely defined by the discrepancy between their vocabulary and their message. One striking example is Bezhin Meadow, where atheist ideology is rendered through Christian imagery, above all in the sequence where a church is ‘deconstructed’. The famous sequence of the gods in October is typical of the way in which the vocabulary of symbols is manipulated to refute the meaning of the message. The principal point of controversy between Eisenstein and the more dedicated Constructivists, especially Vertov, was that for a Constructivist vocabulary determines message. Vertov, a purist in his choice of vocabulary, reproached Eisenstein for betraying the cause of revolutionary art by using actors, traditional narrative components and symbols.

I should like to conclude by quoting Eisenstein’s open letter to the German journal Filmtechnik, in which he responds to Vertov by proclaiming the principle of relativity for the vocabulary any film-maker is free to choose to make his message work:

Whereas today the strongest audience response is provoked by symbols and comparisons with the machine—we shoot the ‘heartbeats’ in the battleship’s engine room—tomorrow we might exchange them for false noses and theatrical make-up. We could switch to make-up and noses.38

Written in 1927, this statement presages and explains Eisenstein’s creative evolution from the Constructivism of The Strike to the theatricality of his later films. For Eisenstein it was but a matter of vocabulary.

Translated from the Russian by Richard Taylor

APPENDIX: EISENSTEIN’S EDITING SCRIPT FOR OCTOBER

Final sequences: shots 326–476 39

326 Crush in cramped premises

327 Empty corridor

328 Ditto. The Jordan Corridor

329 Maelstrom in the corridors./The Jordan Corridor

330 326 again

331 From the crush to amazement./Ante-chamber with people, details of Chinese dining-room

332 48 clock-faces

333 Portières

334 Details. The peacock

335 Stupefaction

336 Do not touch!

337 Tiptoeing. The Pavilion Room. Ante-chamber. Echoes. A suite of rooms

338 Ambush and shooting on the Jordan Staircase

339 Maelstrom at the Jordan Entrance

340 Shooting from the Peter and Paul Fortress

341 A hit beneath the balcony

342 An archway. Solitary bonfires. Near the archway and the Stock Exchange

343 By one of these fires…

344 …is sitting…

345 Panic in the Dark Corridor40

346 Attempt to form ranks by the emergency exit/or in the 1812 Gallery

347 The cadets retreat through the doors

348 The Red Guards advance. Mirrored doors

349 Richly decorated doors

350 The cadets barricade themselves in

351 The door is blocked with gold furniture

352 The door is broken open

353 The door is broken down

354 The panels are broken

355 Chase through Nicholas II’s library

356 Panic in brassières/Billiards and chambermaids

357 Chase through Nicholas II’s library

358 Rosenblatt and book

359 Volley from behind five samovars

360 Children’s chairs/An officer like Skoradinsky

361 Volley from behind the toys. Bicycles

362 A sailor jumps over the model of Laura

363 Women of the shock battalion shooting from beneath the curtains of the

bed-chamber/at the people running in the foreground

364 At the entrance to the bed-chamber an old retainer will not let the sailors in

365 NO TRESPASSING. THIS IS THEIR MAJESTIES’ PERSONAL BED-CHAMBER

366 Women soldiers amidst the curtains

367 The sailors rush past the old man

368 The women soldiers fire a volley

369 They flee to the prayer-room

370 The sailors rush in

371 They search. Rush into the lavatory

372 The women lurking in the prayer-room

373 The sailors in the lavatory

374 The women get away

375 They shoot at the lavatory

376 The sailors run out

377 The feather-bed is pierced

378 They break out through the water-closet

379 They reach the linen-room

380 A sailor with a feather-mattress on his bayonet

381 He looks around him

382 Icons. Eggs. Crosses

383 The sailor

384 Toilet requisites

385 Photographs

386 Icons

387 They open a door: a lavatory (semi-circular)

388 They open a door: a lavatory (rectangular)/Cupboards by the bathtubs

389 The Winter Palace numbers 200 separate lavatories

390 The sailor

391 A statue

392 A bidet

393 Disgusted, the sailor wipes his bayonet

394 He rummages in the linen

395 Breaks the grating

396 Trunks

397 He finds the women amongst the linen

398 The women on their knees

399 The linen flying in the air

400 The sailor says ‘Ugh!’ and lights a cigarette

401 The cadets rush in through the door

402 The cadets take aim

403 The sailor jumps across to the wall/He gropes for…41

404 The cadets take a step forward

405 The sailor raises his hand threateningly

406 Salvo from the Avrora/two-gun/

407 Windows shatter

408 A whirl of feathers

409 Cows panicking

410 The sailor holding a bomb in the whirl of feathers

411 The cadets abandon arms

412 A storm of feathers

413 A boy jumps on to the throne

414 The sailor with the St Nicholas egg in his hands

415 Trunks full of medals are broken open

416 A basket full of eggs is overturned

417 Etuis, cocked hats, gloves

418 Nicholas II’s eggs roll

419 Medals pouring out

420 The crockery is locked up in the pantry

421 The cadets reach the cellar

422 The eggs rolling

423 Shooting

424 in

425 the

426 cellar

427 In the pantry, the ice-boxes, dressers and kitchen are locked

428 Break-in into the mortuary

429 Corpses with numbers on their heels

430 Corpses

431 Torpid government

434 Ovseyenko elbows his way through the Dark Corridor42

435 Fighting in the rotunda/The infirmary

436 Schreider’s men leave the Duma

437 TO SAVE THE LEGITIMATE POWER

438 The cadets are ejected from the cellar

439 Schreider’s men

440 Chichkov, Bulygin and Butylka. Soynikov, Ovseyenko

441 The masses rush forward/The Jordan Staircase

442 The sailors chase the robbers/Vidumkin and her sons

443 Movement in the rotunda

444 The cadets are disarmed/Hands up!/At the Jordan Entrance

445 The stolen items are found

446 Antonova stealing eggs in the ransacked bed-chamber

447 The sailors chase out the robbers/lots of them/

448 Soynikov and Nilov drinking

449 The sailors chase out the thieves

450 The sailors and Schreider’s men by the Politseisky Bridge

451 The cadets holding out in the rotunda

452 Miniature soldiers/from the Alexandrovsky Palace

453 Schreider’s men in ecstasies

454 Senseless/women’s rage/‘Beauvais’ women43/biting and scratching. / Shooting from the attic storey or from the crockery room./A chambermaid

455 ‘Le printemps’ and ‘Les enfants’

456 The burglars press on

457 Frenzied fighting with bottles

458 A cuff44

459 Schreider’s men sit down

460 Fighting with bottles after the flood

461 The treasures of the Hermitage intact

462 They burst into the room where the Provisional Government is sitting

463 The cellar flooding

464 Brutal arrest/Foreground shot of tea

465 Arrest

466 The report to the Congress

467 Schreider’s men with sandwiches

468 Antonov sits down to take the minutes among the bayonets and rifles

469 The Congress rises as one

470 LENIN at the podium

471 CONGRATULATIONS!

472 A peasant, a worker, a soldier at the Congress

473 Sinegub turns up his collar and leaves45/A churchyard

474 Tracking shot of leaflets flying through the air

475 LONG LIVE THE WORLD REVOLUTION!!

476 48 clock-faces

THE END