Who is Susanna Wesley? The quick and obvious response is John Wesley’s mother, the woman behind the founder of Methodism in eighteenth-century England. True as far as it goes, this answer nevertheless limits her appeal to a smaller audience than she deserves. Moreover, it perpetuates the assumption of her own day that a woman’s identity derives from her relationships with close male relatives. It would be a pity if late-twentieth-century interpretation would follow late-seventeenth-and the early-eighteenth-century commonplace and represent her only as the daughter of a prominent Nonconformist minister, Samuel Annesley; as the wife of an Anglican priest who never quite became prominent, Samuel Wesley; and as the mother of Methodist founders John and Charles Wesley, whose undeniable prominence first brought her widespread recognition. Of course, in her day such relationships were underwritten and carefully constructed by contemporary piety, and how much more so for a woman attached to clergy in all demographic directions. Today piety continues to be part of the reason her identity is still dependent on the men in her life. But another factor in our less religious age is the practice of history, which has made useful beginnings but has still not succeeded in recovering the stories of all the notable women or in fully describing women’s experience in the past.

Who is Susanna Wesley? In different communities of interpretation she has been a Methodist saint, an archetype of evangelical womanhood, and even (in a certain psychological reading) an overweening mother who prevented her son from experiencing any marital happiness.1 Most recently, however, as feminist approaches have claimed scholarly prerogatives in literary and historical, as well as religious, studies, her identity is ripe for reinterpretation. There are stirrings that suggest she is becoming something of a foremother for latter-day Christian feminists and an example of early “writing women” who employed intellect and spirituality to subvert (however gently) some of the very religious-based conventions that ordinarily worked to keep women modest, chaste, and silent. Until now, those who would like to pursue such explorations (and could not make forays to the archival collections) have had to work from secondary sources and scattered, incomplete, and sometimes unreliable transcriptions of her own writing.2

In pulling together material for this collection, I am assuming that Susanna Wesley’s own writings allow her finally to speak for herself and yield a richer and fuller identity than she has ever been accorded before. Not that any edition, however complete and however judiciously prepared, can ever avoid constructing her or at least shaping her and in some way prejudicing our interpretation of her. Nor for that matter can archives boast a complete lack of bias—the letters and other papers that survive already represent a process of selection, dependent partly on the reflected glory of her famous son and the concerns of his admiring successors. Despite all that, we still have a remarkably rich collection from which to work. There is no reason that Susanna Wesley’s own voice should not be heard; assessed; and brought into historical, literary, and. theological conversations at the turn of the third millennium.

This new edition will no doubt spark many more readings of her work and life. Some will continue to approach her from within the Wesleyan tradition and find in her writings further corroboration for her status as a sort of Methodist Madonna. Others, prompted (as I have been) by a concern to recover the works of women in various religious traditions, will delve into these pages for clues to women’s struggles and triumphs in more restrictive times and places. Still others, with little commitment to faith or particular interest in the study of religious history, will nevertheless read Susanna Wesley’s religious writings as discourse that encouraged woman’s education and afforded some psychic space, some “room of one’s own,” for her own self-expression and self-development.3 With such readers in mind, I have striven to provide as complete and accurate a collection as possible, edited from holographic and manuscript sources whenever available, and furnished with all necessary annotations and contextual information. It is, I believe, a step in the enriching process of reclaiming another woman’s voice from the past.

The rest of this general introduction will attempt to sketch and characterize Susanna Wesley’s life and suggest how both religious studies and literary historical studies can profit from examining her—and perhaps in the process can contribute to a fuller picture of her. More detailed introductory material, appropriate to the particular writings, will appear in each major part and subsection of the collection.

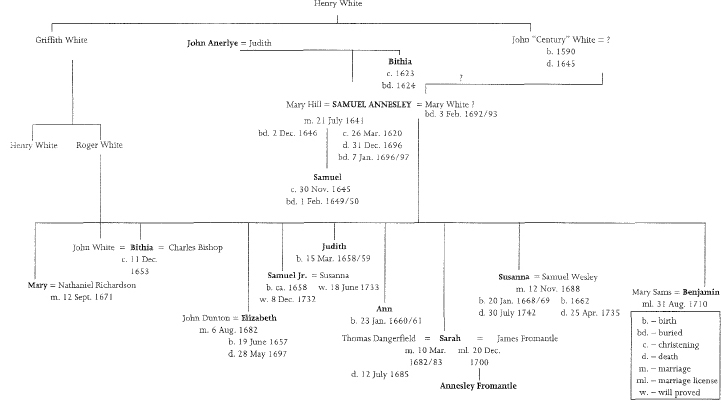

The epitaph on her original tombstone identified Susanna Wesley as “the youngest and last surviving daughter of Dr. Samuel Annesley”4 Born on 20 January 1669,5 she was part of a large family, as an anecdote reported by her eccentric brother-in-law John Dunton amply illustrates. At her baptism (or possibly her younger brother’s)when the officiating minister asked Dr. Annesley how many children he had, the answer was a slightly uncertain “two dozen or a quarter of a hundred.”6 Traces of “only” nine of the Annesley children have turned up in recent research, suggesting that less than half survived infancy, seven girls and two boys. Apart from Susanna, we know little about them, though there are intriguing snippets in Dunton’s autobiography and in a funeral sermon for her sister Elizabeth, Dunton’s wife.7 There is even less information on Annesley’s two wives, Mary Hill (d. 1646) and Susanna’s mother, Mary (?) White (d. 1693), though contextual evidence indicates that the latter was, like her youngest daughter, pious, educated, and energetic.8

Inevitably, we know quite a bit more about Susanna’s father.9 Graduating from Oxford in 1639, he was ordained in Presbyterian fashion and served as a chaplain in the parliamentary navy before settling down as rector of Cliffe in Kent. Additional service at sea kept him away from his parish temporarily, but he soon lost it completely, probably because of his opposition to the execution of Charles I and the fact that there was no great love lost between him and Cromwell. Annesley then moved to London, briefly taking a small parish before being appointed (by Oliver’s son Richard) to the important living of St. Giles, Cripplegate. For nine years he distinguished himself as a preacher and an editor of a sermon series he hosted in the church.

At the Restoration, however, he was ejected from St. Giles in 1662 for conscientiously refusing subscription to the Book of Common Prayer according to Act of Uniformity. Following the practice of many other displaced Puritans, he organized a congregation of like-minded Nonconformists, occasionally running afoul of the laws penalizing such religious Dissenters. His large Presbyterian congregation gathered in Spitalfields, less than a mile east of St. Giles. Though the church no longer survives, Annesley’s nearby house still stands; here he lived; here he worked in his well-stocked study; here his last daughter, Susanna, was born and raised; and here he died in 1696.10 Among his friends and colleagues were numbered all the prominent Nonconformists of the day, including Richard Baxter, and among his parishioners was Daniel Defoe, who published a flattering obituary, extolling him for the “Greatness of his Soul.”11

This quality served him particularly well when his daughter Susanna precociously decided to forsake Nonconformity and join the Church of England, the ostensible cause of his persecution.12 As she indicated in a letter to her son Samuel, this leave-taking was rather remarkable—not only for her youth but also for the methodical way in which she researched and decided the issue.13 Remarkable, too, was the equanimity with which her father responded; as his library shows, he had something of what his most famous grandson would later describe as a “catholic spirit.” Whatever Samuel Annesley’s inner hurt, Susanna “departed” with his blessing and remained his favorite daughter, receiving all his letters and papers at his death. Lacking further evidence, we can only speculate about her mother’s impact on her education and development. However, we can be sure of the powerful gift her father gave her when he affirmed the conscientious choice of an adolescent daughter, even if it registered as a dissent against his cherished Dissenting tradition.

Young Susanna Annesley’s ecclesiastical migration from Nonconformity to the Church of England coincided with a similar move made by a young theological student from Dorset, one Samuel Wesley14 She met him at the time of her sister Elizabeth’s wedding to John Dunton in 1682, possibly at the ceremony itself. Some half-dozen years her senior, he was not only the son but also the grandson of Nonconformist ministers. Like her, and notwithstanding subsidized training in two London Dissenting academies, he also sought membership in the established church. As a man, this afforded him one advantage that Susanna could not have: the opportunity to pursue an ecclesiastical career by matriculating at one of the universities.15 He did so, entering Exeter College, Oxford, in 1684; graduating with a B. A. in 1688; and receiving deacon’s and priest’s orders in the Church of England by 1689. Meanwhile, intellectual and theological affinity had grown,16 as had their love, and the two lapsed Dissenters were married in the parish church of St. Marylebone on 12 November 1688. Thus began a 46 year marriage, ending with Samuel’s death in 1735. As many of the collected letters and journals reveal, it was not always a smooth relationship; but on the whole it probably deserves the label Lawrence Stone has attached to the more enlightened, affective liaisons of the day, a “companionate marriage.” 17

The Annesley Family (1590-1742). From Betty I. Young, “Sources for the Annesley Family,” Proceedings of the Wesley Historicol Society 45.2 (September 1985): 46. Used with permission.

A temporary curacy at St. Botolph’s, Aldersgate, did not bring much in the way of financial support, so the young couple lived in the Annesley household. This arrangement proved useful when Samuel Wesley signed on for a six-month naval chaplaincy (considerably more lucrative than parish work for a beginning clergyman), leaving Susanna behind in her first of many pregnancies. Following the birth of their first son, Samuel Jr., at the Annesleys’, Wesley was invited to fill another curacy, this one south of the Thames at Newington Butts, Surrey. There he served for a year and rented lodgings for himself, Susanna, and young Samuel.18 Still unable to make ends meet, he picked up some literary work on the side; considered emigrating to Virginia; and finally secured his first living in the summer of 1691, the parish of South Ormsby, Lincolnshire.19

Off today’s main road between Louth and Skegness, about 25 miles east of the cathedral city of Lincoln and 150 miles from London, South Ormsby is still in the rural heart of the Lincolnshire wolds. For city-born Susanna, this was a radical change of scene. In this setting, financial problems did not abate, and they were exacerbated by other woes, borne more directly, one imagines, by Susanna. As Samuel Wesley wrote to a friend in 1692

This [i.e., the expense of buying “all sorts of household stuff” together] with first fruits, Taxes, my wives lying in about last Christmass & threatening to do the same the next, & two children & as many servants to provide for (my wife being sickly, having had 3 or 4 touches of her Rheumatism again …) yet has and still does … Reduce Me to greater Extremitys.… 20

The two children spoken of would have been the young Samuel, whom they brought with them from London, and their first daughter, Susanna, born in South Ormsby but also buried there not long after her first birthday. The “threatened” child turned out to be Emilia, their oldest surviving daughter. And four more followed: twin boys, Annesley and Jedidiah, who lived a month and a year, respectively; and two girls, a second Susanna and Mary, both of whom survived into adulthood.

One other detail from the family’s sojourn at South Ormsby merits inclusion to show the young priest’s penchant for getting himself into trouble: the scrupulous rector lost his job by directly confronting the mistress of his patron. As John Wesley later recalled the family story, Samuel was incensed by the woman’s attempts to pay social calls on Susanna:

The Wesley Family of Epworth (1662-1796). Dates in italics are taken from contemporary parish registers or transcripts. From Frank Baker, “Investigating Wesley Family Traditions,” Methodist History 26.3 (April 1988): 162. Used with permission.

Coming in one day, and finding this intrusive visitant sitting with my mother, he went up to her, took her by the hand, and fairly handed her out. The nobleman resented the affront so outrageously as to make it necessary for my father to resign the living.21

A principled but perhaps ill-advised response to local custom, such behavior would bring continuing problems to the Wesley family in their new parish.

Epworth was in its own way more isolated than South Ormsby, situated some 30 miles north of Lincoln in the Isle of Axholme, fen country drained earlier in the century by Dutch engineers. The king presented Wesley to the living in 1695, but he and the family did not take up residence until 1697. They remained there with occasional sojourns in the nearby parish of Wroot, later also held by Wesley, until his death in 1735. Here were born the remaining Wesley children, Mehetabel, Anne, John, Martha, Charles and Kezia, all of whom survived, as well as four to six (such is the uncertainty of the details about a couple of these short-lived babies) who did not.22

Even given the Wesleys’ love for the written word (and subsequent Methodists’ attempts to preserve every scrap they produced),23 the texture of family life during the 39-year Epworth period is not fully recoverable. Nevertheless, certain patterns and certain particular incidents stand out. If they have been staples of Wesleyan legend in the past, they deserve continued attention when viewed from Susanna’s perspective; and, in fact, most of these are well represented in her writing, some even finding their original expression there.

The details of daily life occasionally gain expression in Susanna’s writing: managing a household, facing illness and other such “afflictions,” and raising and educating a large family. The perennial family debts, due in part to Samuel’s mismanagement and inattention, weigh heavily on her and sometimes find expression in her letters. It was a major concern, for instance, in the long letter to her brother Samuel Annesley Jr., a merchant in India, from whom the family expected some financial aid. In the process of outlining their needs (and defending Samuel Wesley’s ability to manage money wisely), she alludes to the time in 1705 when her husband was detained in debtor’s prison in Lincoln. She writes of the “testimony” she had given at the time to the Archbishop of York, whose aid she sought. In answer to his question about whether the family had “ever really wanted bread,” she had replied:

My lord … I will freely own to your grace, that strictly speaking, I never did want bread. But then I have had so much care to get it before ‘twas eat, and to pay for it after, as has often made it very unpleasant to me. And I think to have bread on such terms is the next degree of wretchedness to having none at all.24

While Archbishop Sharp had been touched and responded with“a handsome present,” her brother was unmoved by the implication that he should follow suit and barely mentioned the Wesleys in his will.25 As other of her letters (and those of her husband) bear witness, their finances were often in this straitened mode.26

As the one who ran the household, Susanna felt responsibility for their plight, and thus the topic occasionally intrudes even into her devotional life. Her journal recalls, for example, her bargain with God to worship more sincerely in return for an easing of financial pressures:

You did sometime since make this vow, that if God would in very deed give you food to eat and raiment to put on without exposing you to the temptation of anxious care or reducing you to the necessity of borrowing for the necessaries of life, that then the Lord should be your God.27

Next to money problems, ill health seems to have challenged her most on a continuing basis—-not surprising given the energy drain of her reproductive life and the “primitive physic” available from eighteenth-century medicine. Already noted above from their time at South Ormsby were the “three or four touches of rheumatism” that afflicted her even as a young woman.28 In her correspondence, there are at least a dozen mentions of her bouts of illness, though usually without any specific description. In an early letter to her son Samuel, she is “so ill.” In another she explains why she and her husband were sleeping in separate rooms the night of the rectory fire: “I having been very ill, we were obliged to lie asunder.” In early 1722 she writes her brother, perhaps exaggerating for sympathetic effect, “I am rarely in health.” In the autumn of 1724, she escapes the small pox that the rest of the family contracted but is “very ill, confined to my chamber” the following February. In summer 1727 she reports “very ill health,” the following year is laid low by fever and sickness, and the summer after that is “ill for want of tea” (and happy therefore to have a present of tea—and chocolate). Letters from the decade of the 1730s (her 60s) almost always assume ill health, only mentioning situations in which she feels somewhat better. Occasionally, as in a letter to her son Charles (well after her husband’s death and her departure from Epworth), her difficulties serve as apologies: “I should write oft’ner had I better health.”29 Health was for her, as for most people, a natural concern, heightened in her day no doubt by the relatively primitive state of sanitation, medicine, and birth control. It was also a subject for spiritual reflection, so that its preservation was a blessing to thank God for and its dissolution was an affliction, like poverty, to be improved “to our spiritual advantage.”30 The bottom line, both on fortune and on health, is probably accurately expressed in a letter to Samuel Jr. a few months after the rectory fire in 1709. “Truly my health and fortune is much alike,” she writes, “neither very good or extremely bad. I have constantly pain enough to mind me of mortality and trouble enough in my circumstances of fortune to exercise my patience.”31

By all odds the greatest concern of her day-to-day life was her role as educator of her children. Explicitly present in her famous child-rearing letter of 1732,32 as well as in her other “catechetical” essays and numerous journal entries, this focus is also implicit in virtually every letter to her children. Heir to the traditional Protestant concern for education as embodied both in her Puritan upbringing and in her adopted Anglicanism,33 Susanna also absorbed many of the newer intellectual assumptions of her own age, voraciously reading contemporary “practical divinity,” with its penchant for the “reasonableness” of “natural and revealed religion,” and keeping current with such intellectual pace-setters as John Locke.

Though her initial educational attempts with her first pupil Samuel Jr., must have taken place in South Ormsby—apparently something of a slow start34—the process began in earnest in the Epworth rectory. Here, in what John Newton describes as an atmosphere resembling “a small private boarding school,”35 she wasted no time putting her children into “a regular method of living” from birth and then taking them aside on their fifth birthday to teach them the alphabet and start them off on the first chapter of Genesis. The personal attention continued in necessarily methodical fashion: each pupil had her or his special day of the week for a one-on-one tutorial with the headmistress.36 As the letters to her grown sons and the essays prepared particularly with her daughters in mind indicate, she never forsook her pedagogical role, even when her children graduated from her classroom.37

The results of the Epworth experiment in home schooling were gratifying enough in their own day. Three boys were well prepared for a career track that led to actual boarding schools in the metropolis, to Oxford, and thence to ordination in the Church of England. And the seven sisters received equal preparation, well beyond the normal expectation of their gender and community. Susanna cannot be blamed if that was to their detriment when it came to finding suitable intellectual matches among the young men of the fens, marriage being the primary assumed “career” of a clergyman’s daughters.38 Beyond the immediate pedagogical success, however, many observers have additionally supposed that Susanna’s schoolroom and rectory life in general put the initial discipline, the original “method,” in John Wesley’s Methodism and ensured that a continuing ideal of the movement would be the joining of “knowledge” with “vital piety.”39

These general elements of family life provide a backdrop for several particular incidents, which leap from Susanna’s writing and give vivid testimony not only to “remarkable occurrences” in Wesley family history but also to the extraordinary character of its matriarch. Worth mentioning briefly are the rectory fire of 1709; two signal occasions of Susanna’s conscientious insubordination, to husband and governmental authority in one case and to husband and ecclesiastical authority in the other; and the saga of the notorious family poltergeist.

The rectory fire of 1709 is a key reference point in the Methodist story, giving John Wesley himself and thousands of the faithful thereafter an example of providential intervention. Given up for lost, he was snatched from a fiery upstairs room, “a brand plucked from the burning,” a person chosen for God’s future purposes.40 The event is also central to Susanna’s life and experience.

The fire exemplifies the difficulties that came too regularly to the rectory family to be described as merely bad luck. Rather, like their dismissal from South Ormsby and like the financial problems that plagued the family, the fire was probably attributable to the rector’s running afoul of disgruntled parishioners. Not that he should be held responsible for the extremes of rough justice that local men sought to impose on the aloof scholarly, stubborn outsider. Already, the attempts of local retribution had included threats of harm during the parliamentary election of 1705 and, indirectly, the death of a nameless newborn son; a trip to debtors’ jail in Lincoln; and the maiming of some of his animals.41 From this perspective, the flames that engulfed the rectory on the frosty night of February 9, 1709, were only the latest and most vicious assault on an unpopular parson.

The family, including the nearly lost young “Jacky,” survived the fire unscathed, but otherwise the losses were complete and devastating. House, furniture, clothing, money (just received for some crops), a “good quantity” of some additional crops, all their pewter and brass, all but “25 ounces of plate,” some hemp and corn, and a few sticks of lumber were gone, the makings of continuing financial disaster. Perhaps even more distressing was the loss of Samuel’s books and manuscripts, including one ready for the press (worth £50 to the family fortune), and the destruction of the letters and papers willed to Susanna by her late father. A further casualty was Susanna’s own manuscripts; everything we have of hers apart from a few letters preserved by their recipients thus dates after the fire.

Without minimizing the ruinous effects of the fire, Susanna Wesley nevertheless came away from it focused and reinvigorated for the rest of her life. She was on the verge of menopause, her last child, Kezia, being born either in 1709 or 1710. This impending change of life thus coincided with the fire and produced a renewed devotional life, the result of which may be seen in the journals I have collected in part two of this volume. The transition to a motherhood that no longer involved childbearing may have reinforced the conviction born out of her contemplation, and in practical response to the farming out of her children after the fire, that a revitalized sense of educational purpose was called for. In October 1709 she wrote Samuel Jr., still a pupil in Westminster:

There is nothing I now desire to live for, but to do some small service to my children, that, as I have brought ‘em. into the world, so that it might please God to make me (though unworthy) an instrument of doing good to their souls. I had been several years collecting from my little reading, but chiefly from my own experience, some things which I hoped would ha’ been useful to you all… ,42

Thus began the arduous project of sustained writing that makes up the bulk of part III of this volume: an exposition of the Creed, a partial exposition of the Decalogue, and a dialogue on natural and revealed religion. Here again. Susanna “improved” the affliction, in this important instance gaining a second wind and reviving her sense of vocation for the remainder of her life.

We have already noted Susanna’s independence of character when, as a well-read, strong-willed preadolescent, she forsook her father’s Nonconformity. Now we may follow the same trait as it was played out on two occasions, a decade apart, in her married life. The first instance took place when Susanna refused to add her “Amen” to Samuel’s prayer for the king one evening in late 1701 or early 1702. Though both were High Church and Tory, Samuel was favorably disposed toward William and Mary, who had been invited to rule by Parliament in 1688, while Susanna regarded them as usurpers. She believed James II continued to be king by divine right. It is somewhat unclear why she waited so long to register her protest—Mary, with Stuart blood in her veins, had died in 1694, leaving William to reign on his own in the eight intervening years. Perhaps it was the death of the exiled James II in 1701 that brought the whole issue to mind.43

In any case, the significant omission at family prayers was noted by the rector, who confronted her and, when she refused to recant, took a solemn oath not to touch her until she begged forgiveness. She remained obstinate, and they broke off marital relations for nearly half a year. John Wesley’s version of the story included his father’s memorable line, “You and I must part: for if we have two kings, we must have two beds.”44 Susanna’s version, much more complete and intriguing, may be read in her first four extant letters, in part I of this volume. She wrote for counsel to natural allies: a local noblewoman who had been a maid of honor in the Stuart court and one of the most prominent Nonjurors, that sect of divine-right Anglicans who conscientiously refused to swear allegiance to William and Mary.45 The issue for them in the wider political arena and for Susanna in her marriage was liberty of conscience. Ironically, a signal trait that had been instilled in her from the Dissenting side of the English religious spectrum was now employed for the sake of an ultra-High Church cause. With the support of Lady Yarborough and the Rev. George Hickes (he had written her, “stick to God and your conscience which are your best friends”),46 Susanna stood her ground. Only after some time in London and a fire in the rectory (not as destructive as the later one, though bad enough) had brought Samuel to his senses were the two finally reconciled. The fruit of their reconciliation arrived June 17, 1703, a baby boy, christened John.

The saga of Susanna standing up against Samuel’s (and conventional authority’s) sway was to recur a few years after the 1709 rectory fire. In the winter of 1711— 1712, the offended authority was not so much political as ecclesiastical convention. Samuel, in London as a delegate to the Church of England’s convocation, got word from his temporary curate that parishioners were absenting themselves from morning prayer in favor of an irregular Sunday evening service conducted by Mrs. Wesley in the rectory kitchen. Wesley wrote back rebuking his wife, and she replied with a strong letter that answered him point by point, claiming her right to exercise a kind of ministry in his absence. To his objection about a woman presiding at public worship, she replied:

As I am a woman, so I am also mistress of a large family. And though the superior charge of the souls contained in it lies upon you, as head of the family, and as their minister, yet in your absence I cannot but look upon every soul you leave under my care as a talent committed to me under a trust by the great Lord of all the families of heaven and earth.47

She further explained that she had been inspired by an account of Danish missionaries in India “to do somewhat more than I do,” beginning with her own children—thus the genesis of her scheme of individual meetings with each of them once a week. The inspiration also increased her zeal in the conduct of Sunday evening family prayers, and when the circle of attenders widened and servants’ families and then the general public sought to attend, she felt she could not turn them away. The limit, in fact, got to be the capacity of the rectory ground floor, something on the order of 200. The rector was still not convinced and wrote her again, asking her to stop. In due course she replied with a further account of the good her “society” was doing among the people and concluded with one of her more stunning rhetorical flourishes:

If you do after all think fit to dissolve this assembly, do not tell me any more that you desire me to do it, for that will not satisfy my conscience; but send me your positive command in such full and express terms as may absolve me from all guilt and punishment for neglecting this opportunity of doing good to souls, when you and I shall appear before the great and awful tribunal of our Lord Jesus Christ.48

The rector relented; Susanna’s conscience had once more withstood husbandly and churchly attempts at control, though this time her actions more closely paralleled her ancestral tradition of Nonconformity. Not believing she had contravened any law, she nevertheless had created a competing institution (an irregular “cov-enticle” according to her accusers) when the church could not provide for the needs of the parish as she perceived them. Years later, John Wesley, who had been present at the Sunday evening meetings as a boy of nine, read over the correspondence after his mother’s death, and concluded, “I cannot but farther observe that even she (as well as her father and grandfather, her husband, and her three sons) had been, in her measure and degree, a preacher of righteousness.” 49By then, Wesley himself had replicated the same model in his own Methodist societies and was here implicitly acknowledging another debt to his mother.

Any description of the Epworth years is incomplete without a mention of Old Jeffrey, the poltergeist that plagued the rectory during December 1716 and January 1717 and has bedeviled historians ever since. A variety of noises and apparitions immediately attracted the household’s attention, first the servants and the children, then Samuel and Susanna. Letters to Samuel Jr., by then teaching at Westminster School, quickly aroused his curiosity and that of his brother John, also in London, a pupil at Charterhouse School. The correspondence from Epworth and the informal depositions that John took in 1720 constitute what one writer on psychic phenomena called the “most fully documented case in the history of the subject.”50 This evidence fascinated others, as well; at the end of the century, it surfaced in the hands of the chemist and Unitarian minister Joseph Priestley, who published it to demonstrate John Wesley’s captivity to that bane of eighteenth-century rationalism, “enthusiasm.”51

John Wesley indeed was predisposed to believe in the existence of an invisible supernatural world and thus was ready to accept his family’s evidence at face value, another good argument against atheism, Deism, and materialism. Each member of the family, except daughter Hetty, reported his or her experiences in straightforward fashion, as did a hired man and a neighboring clergyman. There seems to have been no apparent hoax. Indeed, in years of wrestling with it, no obvious and satisfying explanation has emerged in bemused Methodist historiography, either.

More to the point of our discussion is what the poltergeist meant to the family, particularly Susanna, and what that says about the worldview of the Epworth rectory. Because one of the poltergeist’s favorite disturbances was to knock during the rector’s evening prayer for the king (by then George I), the family concluded that the ghostly being had Jacobite leanings. John went so far as to connect the hauntings to his father’s rash oath on the occasion of Susanna’s refusal to say amen to his prayers for King William IS years earlier. He wrote, “I fear his vow was not forgotten before God.”52 The eldest daughter, Emily, suggested that the commotions might have some link to an alleged outbreak of witchcraft in a nearby parish, which had moved Samuel to preach “warmly against consulting those that are called cunning men, which our people are given to.” As this occurred just before the onset of Old Jeffrey, she concluded that the supernatural visitant was acting to spite the rector, though it might also suggest another subset of flesh-and-blood parishioners with a motive to disrupt the pretentious inhabitants of the parsonage.53

Susanna herself was initially skeptical at the reports of the servants and children. On first hearing noises, she suspected rodents and called in someone to blow a horn to drive them away. Bat the tactic did not work, and matters deteriorated. Noises (groans and all matter of knockings, stampings, and clatterings) and appearances (Susanna thought she saw a badger-like creature scurrying across the floor) became too outrageous to deny. At length she decided the visitation portended the death of a close relative, either the rector or someone at a distance, such as Samuel Jr., en route to London, or her brother in India. Finally, at about the time the ghost gave up the rectory, she expressed exasperation at her son Samuel’s continuing curiosity about “our unwelcome guest.” She was “tired with hearing or speaking of it” and invited the young man to come home to Epworth and experience it for himself.54

The episode paints in bold, relief Susanna’s, her family’s, and perhaps the age’s continuing predisposition toward supernaturalism against the background of reasonableness and science. Priestley and other eighteenth-century commentators might accuse her of enthusiasm and credulity. We might more charitably contend that the irrational and the emotional imply another, not necessarily an inferior, worldview, an alternative discourse in which a woman could express and discover herself quite well—especially when held in tension with rational and experiential considerations. Pascal himself, another anomaly of the era, whom Susanna read and commented on in her journal, expresses an appropriate agnosticism for those rationalists who would too quickly foreclose on the “superstitious” side of eighteenth-century thought: “the heart has its reasons which reason cannot know.”55

The death of Samuel Wesley Sr. in 1735 signaled the beginning of a new life-phase for Susanna. In addition to the loss of her husband of some 46 years, it also meant her removal from the Epworth rectory (a place that for all the disruptions had been home for nearly as long). Now she would no longer be mistress of a household but would sojourn for a seven-year period as a guest, albeit a welcome one, with various of her children. She first stayed with Emily, now a schoolmistress in nearby Gainsborough. Then she moved southwest to live with Samuel Jr., a headmaster in Tiverton, Devon, leaving him two years before his unexpected death in 1739 to be with her daughter Martha (called Patty) and her clergyman husband, Westley Hall, in three locations (Wooton, Wiltshire, near Malborough; Fisherton near Salisbury; and London). From that last brief arrangement it was an easy step to finally take up residence with her son John at his London headquarters, the Foundery, within hailing distance of her birthplace.

Communication with friends loomed larger in her final years, as several of her letters attest.56 Staying with her children in various corners of the land allowed her to make new friends, as far as we can tell from letters, all female. One such was Alice Peard, a woman she met while staying with Samuel in Tiverton and wrote to at least once after joining Martha and Westley Hall in Wiltshire. Another was the countess of Huntingdon, an influential player in the evangelical revival, who had sent her a bottle of madeira and, apparently, a generous gift of financial support at the Foundery.57 Tf some of her new acquaintances were not up to that standard of affability and/or generosity58 that did not cause Susanna to pull back from social contacts in her advanced years.

Although friends could help her deal with the loss of husband and home and all the difficulties that came with widowhood and aging, they were no substitute for family. Thus, she began to rely on her children, not just for room, board, and financial support but also for their visits and, when that was not possible, their correspondence. For instance, the string of letters to Charles in 1738 and 1739 contain frequent references to the help, both temporal and spiritual, that he and John were providing her. She expresses her strong desire to be visited by Charles so they can talk over some of her problems. She would even like more time with John, whom she infrequently saw. She wrote of him:

My dear Son Wesley hath just been with me and much revived my spirits. Indeed I’ve often found that he never speaks in my hearing without my receiving some spiritual benefit; but his visits are seldom and short, for which I never blame him, because I know he is well employed, and, blessed be God, hath great success in his ministry.59

To this example of family support may be added one other episode, reported in a conversation with John. She spoke to him of the strong sense of forgiveness she felt while receiving the cup from her son-in-law Hall at Communion one Sunday in August 1739. Though John and Charles both made a bit too much of the incident, “assurance of pardon” being an expected mark of Methodist experience, and though she would have been scandalized had she known of Hall’s unfaithfulness to her daughter, which came out only later,60 Susanna was genuinely touched. She, who had spent most of her life serving others, could at this point in her life also gratefully receive service from those close to her.

This is not to say that she had become passive and had relinquished her maternal, intellectual, and theological authority. She still had an active mind and continued to advise and confront when occasion demanded. While fiercely proud of her sons’ evangelical work, she was not above puncturing some of their early enthusiastic pretensions, as when she accused Charles of falling into “an odd way of thinking” in saying he had “no spiritual life nor any justifying faith” before his conversion earlier that year.61 Her misgivings were not to be taken as disavowals of the Methodist movement, as some of John’s and Charles’s enemies tried to make it seem, but rather attempts to further the important work she saw them doing.62

Perhaps the best example of her continuing decisiveness involves her role in convincing John to adopt one of the most important innovations of the movement, the employment of unordained but spiritually gifted people in preaching. One Thomas Maxfield began the practice without permission during one of Wesley’s frequent absences. Before returning to take care of the situation, Wesley spoke to his mother, who replied, “My son, I charge you before God, beware what you do; for Thomas Maxfield is as much called to preach the Gospel as ever you were!”63 Taken aback by her blunt statement and perhaps remembering her own “irregular” preaching in the Epworth rectory years before, he saw her wisdom and adopted the new practice, which developed into a trademark of Methodism and one reason for its early success.

The culmination, in many ways, of her life’s work was the final document of this collection, her anonymous pamphlet of 1741 that defends her son John in his quarrel with George Whitefield. Some Remrirks on a Letter from the Reverend Mr. Whitefield to the Reverend Mr. Wesley, in a letter from a Gentlewoman to Her Friend brought together in a public way several important strands of her life. First, it called on her adversarial personality, nurtured in Puritanism, further cultivated in her Nonjuring phase, and continually reinforced in the struggles of her personal and devotional life. Second, it allowed her to demonstrate her intellectual acuity, to draw on her wide reading, and to employ the ready style she had developed in all her years as a closeted writer. Finally, public and private concerns coincided when she was able to identify her sons’ cause with God’s intention for the nation and defend them both. Though it might have been more gratifying to have her name on the pamphlet’s title page, her anonymity seems appropriate: she had the quiet satisfaction of seeing her work in print and yet could assure herself that she was not transcending the boundaries of female modesty. And perhaps there was, in addition, the canny realization that the work would be more effective if readers did not perceive it as a mother defending her son.

Susanna Wesley’s England, Susanna Wesley began and ended her life in London but spent most of it in the remote Lincolnshire parish of Epworth (and its yoked neighbor, Wroot). After leaving London and before moving to Epworth, she lived in South Ormsby, her husband Samuel’s first parish, also in Lincolnshire. Following her husband’s death, she sojourned briefly with various of her children—in nearby Gainsborough, Tiverton (in the southwest), Wooton, and Salisbury (in south-central England)—before she finally returned to London.

Susanna Wesley’s London. Susanna Annesley was born and raised in London, married Samuel Wesley there, and bore her first child there. After many years away, she returned as a widow and died there, under the care of her son John.

Susanna Wesley as a young woman. Late-nineteenth-century engraving, possibly from an autlientic early portrait. A copy of the engraving hangs in the Old Rectory in Epworth.

Susanna Wesley at age 68. John Williams, a pupil of Samuel Richardson, painted Susanna’s portrait in 1738, several years before her death. This engraving was made from the portrait a year or two after she died. The portrait has survived and is currently owned by Wesley College, Bristol, but it was inaccurately restored with a younger woman’s face in 1891. The engraving is therefore probably her most authentic likeness.

Susanna Wesley as an older woman. W H. Gibbs engraving, following the original John Williams oil painting of 1738. Taken from the frontispiece of John Kirk, The Mother of the Wesleys, 6th edition (London: Jarrold and Sons, 1876).

Susanna Wesley’s birthplace, Spital Yard, off Bishopsgate, London. Her father, the dissenting minister Samuel Annesley, and his family lived here at some point following his ejection from the living of St. Giles, Cripplegate, in 1662. Susanna probably also stayed here briefly as the young wife of Samuel Wesley during his brief chaplaincy on a man-of-war. During that period, her first son, Samuel Wesley Jr., was born in 1690. The building has survived— though just barely—the 1990s commercial development around Liverpool Street Station.

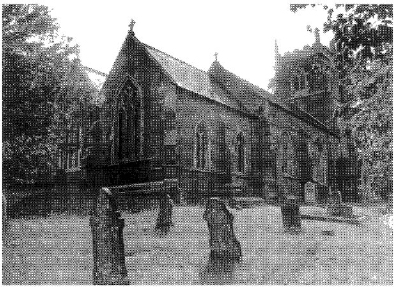

St. Leonard’s Church, South Ormsby, Lincolnshire, Samuel Wesley Sr.’s first ecclesiastical preferment. During the family’s time in this rural parish (1691–1697), Susanna Wesley bore six children, three of whom died in infancy.

St. Andrew’s Church, Wooten Rivers, Wiltshire. Susanna lived in the rectory of this agricultural parish with her daughter Martha and son-in-law, the Reverend Westley Hall, in 1737–1738, before moving with them to the Salisbury suburb of Fisherton in 1738 and finally to London in 1739.

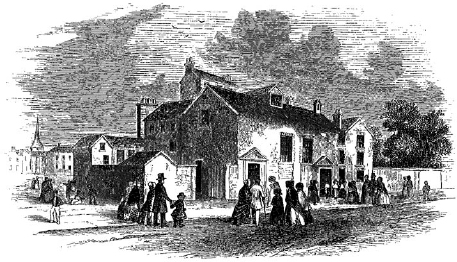

The Foundery, formerly a royal foundry for cannon, was renovated and used by John Wesley as his London headquarters from 1740 to 1778. In addition to a preaching house, a schoolroom, and his own apartments, the facility afforded space for traveling preachers and their families and for his mother, Susanna Wesley. Here, probably in the gabled section on the right, she lived the final two years of her life. Here she died on 30 July 1742.

Susanna Wesley’s grave, Bunhill Fields, London. After Susanna’s death in 1742, John Wesley buried his mother in this dissenters’ cemetery across City Road from the eventual site of his chapel (built in 1774). The stone, recently cleaned and restored, actually dates from 1828, when Methodist officials replaced the original, less-descriptive one put there by her son. Her neighbors in Bunhill Fields include John Bunyan, Isaac Watts, and William Blake.

Mother and son were together at the end, Friday, 30 July 1742, as were most of her surviving daughters. Before she lost her speech, she had addressed them, “Children, as soon as I am released, sing a psalm of praise to God,” and they afterward obliged her. “An innumerable company of people” gathered for her funeral, John preached the sermon, and she was buried (appropriately, given both her origins and her own dissenting style, even as an Anglican) in the Dissenters’ burial ground in Bunhill Fields just across from the future site of Wesley’s City Road Chapel. Commented Wesley in his Journal, “It was one of the most solemn assemblies I ever saw, or expect to see on this side eternity.”64

The basic hagiographical, not to say romantic, view of Susanna Wesley is well exemplified in Adam Clarke’s early-nineteenth-century assessment. Recounting her roles as wife, mistress of a large family, Christian, mother, and friend and the impact she had, especially on John Wesley, he exclaims, “If it were not unusual to apply such an epithet to a woman, I would not hesitate to say she was an able divine!” He confesses not having seen her like among all the pious females he has known, heard of, or read about, and he concludes by inserting her name into the famous description of a good woman in the book of Proverbs: “Many daughters have done virtuously: but SUSANNA WESLEY has excelled them all.”65

“Able divine” and “good woman” are not bad places to start in any overview of Susanna Wesley. Without capitulating to the hagiographic and romantic readings of the past, we may nevertheless contend that she deserves a place both in theological discussion and in the wider consideration of women’s history. Granted, Clarke’s first phrase sounds a bit quaint (and a bit obvious, now that women have long since filled ministerial roles); and early Methodists and late-twentieth-century feminists might disagree on the meaning of the second catchall expression, the proverbial good woman. But if “able divine” may be employed to suggest a particular vocational subculture (a language, a set of theological and devotional assumptions, a worldview) and “good women” can hint at the more generic sense of what it has meant for women to excel, these two descriptions may not be far from the mark. If so, Susanna Wesley may prove to be a fit subject for feminists and for those who study women, their history, and their literature, as well as for Christians and for those who study that tradition and its interaction with society and culture. Our age may not regard her as St. Susanna, mother of St. John, any longer, but it might justly discover her to be a competent, practical theologian-educator and a complex and extraordinary woman in her own historical context.

It will not be difficult to convince religionists to take a fresh look at Susanna, particularly those who stand in and/or study any of the same traditions that she inhabited: the Puritan, the Anglican, and the Methodist. For them, Susanna’s life and work provide clues to the links between and among these three important strands of English Protestantism. For instance, those searching for the origins of Methodist religious experience and emotionalism might usefully find in Susanna a connection to what Gordon Rupp has called a “devotion of rapture” among English Puritans.66 Students of John Wesley’s sometimes troublesome doctrine of Christian perfection, and for that matter Anglicans interested in the development of the “holy living” strand of their tradition, might notice Susanna’s own wrestlings with that subject as guided by the blind Welsh theologian Richard Lucas.67 In a waning ecumenical age, when communities are urged to celebrate their particularities, constructive attention might be paid to the tension between partisan identity and “catholic spirit” as it plays out in Susanna Wesley’s life. How could she read so widely (Puritans, continental Catholics, all stripes of Anglicans) but at times focus so narrowly (e.g., in her Nonjuring phase) and yet over the course of her life find some sort of continuity in three movements in early modern English religion?

An obvious special focus of current religious studies of Susanna Wesley is her femaleness. How did gender affect her participation in religious life? How did the religious traditions that she was part of condition, limit, and possibly liberate her? In two earlier studies I have attempted to discover some of the possibilities. I have argued, for instance, that certain elements of her spirituality (conscience, reason, and religious experience) did in fact act as solvents “against the patriarchal biases then prevailing.”68 I have further explored her intellectual life—her reading and the writing amply displayed in this volume—as a factor in the resistance she mustered against her father, her husband, her sons, and her pamphlet opponent George Whitefield, in effect, against the patriarchal authority of the Establishment.69 Among other discoveries or confirmations that emerged in her writing, “a conscience void of offense,” a God-given reason that is closely related to self-reverence and the “dignity of your nature,” and the experience of “loving and being beloved by [God],” all might offer a woman the eighteenth-century equivalent of empowerment.70 The premium put on education and literacy by Protestantism, particularly in its Enlightenment phase beginning in the late seventeenth century, could be applied with revolutionary effect to women as well as to men. This is not news to students of Western religion, though surprisingly few have paid attention to the period between the Civil War sects and the rise of Methodism.71 A thorough reconsideration of Susanna Wesley, based on the documents assembled here, should immensely enrich our understanding of that process.72

Though some literary historians have neglected women who wrote in a spiritual vein,73 others have recognized them, deferring to the number of women writers if not to their theological assumptions. As Patricia Crawford has noted, “Religious writing of various kinds was the most important area of publication for seventeenth-century women.” And the same would be true, if to a somewhat lesser extent, in the eighteenth century.74 Women like Susanna who wrote out of a religiously constructed worldview are beginning to gain the recognition of scholars in this field. And the day is not far off when Susanna herself will garner similar notice: she— along with her sometime black sheep daughter Hetty, that is, Mehetable Wright,75—has recently been certified as a “woman writer” in the spate of dictionaries and “companions” that are beginning to recover names and sources.76

In fact, feminist literary historians have already made helpful approaches. Opening up the literary canon to religious women writers has involved paying positive attention to previously ignored “women’s” genres such as the diary, autobiographical writing, the meditation, and the conversion narrative.77 Each of the three genres that we have identified in her writing and used as organizing principles in this collection—letters,78 diaries,79 and published essays80—have been illuminated in recent work.

Clearly, whether we read Susanna Wesley as an early “able [female] divine” or simply as a “good woman” who wrote and lived in a religious idiom, like many another in her day, we can no longer regard her only as John Wesley’s mother. She most assuredly is that, and that relationship brought her to public view and led to the preservation of the documents we can now proceed to explore. As we delve into these texts, though, her identity may begin to emerge in a richer form than ever before. Who is Susanna Wesley? Mediated by her own writings, a woman of her own time and place, she emerges in these pages as a complex and compelling personality who has much to teach.

I have organized Susanna Wesley’s work into three parts, corresponding to three discernible genres that she employed. Part I consists of her letters, which are the best-dated and most complete record of her connection to her family and the world around her. Part II offers her devotional diaries. They are rarely dated, probably from a relatively narrow slice of years early in the century, but they open up her spirituality and, more clearly than the other writings, reveal her deepest self in process. Finally, part III presents her longer theological and educational writings—not that these themes are absent from letter and journal, but they are more sustained here, written with self-consciousness and intended for either real or informal publication. This is Susanna boldly trying her hand at a “male” task, albeit for the best of female motives, the education of her children and the defense of her son.

In general I have sought to present the most accurate transcription of Susanna Wesley’s own writing consistent with easy comprehension by the modern reader. I wish to avoid her Victorian editors’ attempt to expunge, correct, dress up, and otherwise tamper with her work. At the same time, I have restrained the urge to reproduce a text so exactly that every archaism and quirk of handwriting becomes a stumbling block to the interested general reader.

In pursuit of this goal the following guidelines have been used.

Spelling has been corrected and usually modernized, using the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as standard. For instance, chuse becomes choose, but centre and Saviour remain as they are—Susanna should still be allowed to write with a British accent. Commonly occurring colloquial or shorthand spellings such as bin and som and coud are regularized to been and some and could.

Contractions and abbreviations are expanded unless they indicate speech patterns that would otherwise be lost. Thus ‘tis and I’ve and ‘em are maintained, but wn is expanded to when and yt becomes that.

Punctuation has been left alone unless alterations are required for sense or to avoid the distraction of excessive use, for example, of commas. Many of her sentences, particularly in letters and journal, tend to run on without adequate punctuation, in which case I have revised them according to modern convention and my own best judgment. Her sometimes excessive use of exclamation points is occasionally left as is to indicate her emotional state; when I have limited them a bit to preserve the flow of her sentences, I have so noted. Though she does occasionally employ quotation marks, I have frequently introduced them as part of my editorial attempt to track down her use of biblical and other material, and I so indicate in the notes.

I have tried to follow manuscript paragraphing, but given the excessive length of some of her paragraphs, I have from time to time introduced my own, and I have so indicated.

Notes, in addition to citing sources of quotations and allusions when available, also provide definitions of technical theological terms and archaic usage and give some more wide-ranging explanations if they have not already been covered in introductory material. Definitions have been taken, usually uncited, from the Oxford English Dictionary.

Thankfully, other textual apparatus has not often been necessary, but the following should be kept in mind:

[Brackets] are used for editorial insertions where the text is deficient but a fairly reliable guess may be made. Also, where noted in one or two instances, brackets are employed to indicate manuscript variations.

[?] precedes a probable reading of an illegible word.

Ellipses (…) indicate omissions in a manuscript, for example, when the only manuscript of a letter is the excerpted copy in John Wesley’s letter book.

A blank (———), occasionally employed by Susanna herself, indicates words, usually names, that she intentionally omitted on her page.

Italics in text indicate Susanna’s own underlining, unless otherwise noted. (Note, however, that such emphasis could have been added by any subsequent reader of the manuscript.)

1. Typical of the hagiographic tradition is John Kirk, The Mother of the Wesleys: A Biography, 6th ed. (London: Jarrold, 1876), first published in 1864. That S. W (I will employ her initials for brevity’s sake in the notes) was promoted as a saintly model is clear from the bookplate inside my second-hand copy of Kirk. In 1898 it had been awarded to a young woman, Myrtle Hodge, for winning the Circuit Prize (Middle Division), Examination in History of Methodism, by the Cornish Wesleyan Methodist Church Council. Elsie G. Harrison, Son to Susanna: The Private Life of John Wesley (London: Ivor Nicholson and Watson, 1937), argues John’s continuing emotional links to his mother. Writing of his most promising relationship with a woman, Harrison observes, “It was clear that neither Grace Murray nor anyone else ever really had a fair chance with John Wesley. S. W had seen to all that under the old thatched roof of Epworth Rectory …”(p. 323.)

2. All told there are at least a half dozen full-length biographies and a host of articles or parts of larger works that treat S. W’s life. John Wesley himself began the hagiographical tradition during the eighteenth century in the pages of his Journal and his Arminian Magazine, (AM) in which anecdotes, references, and some of her writings take their place with notices of other exemplary Christians. The beatification continued in 1823 with the English publication of Adam Clarke’s Memoirs of the Wesley Family; Collected Principally from Original Documents (New York: N. Bangs and T. Mason for the Methodist Episcopal Church, 1824). As the subtitle suggests, this volume is an anthology, as well as a biographical-hagiographical study. S. W is the focus of about a fifth of the book, which deals with the entire Wesley family except for John and Charles. See the Bibliography for a more complete listing of relevant works. And see also John Newton, the author of the best biography, Susanna Wesley and the Puritan Tradition in Methodism (London: Epworth, 1968), for his analysis of his predecessors in that endeavor, “Susanna Wesley (1669-1742): A Bibliographical Survey,” Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society [subsequently, PWHS]37 (1969-1970): 37–40. For an introduction to the subsequent mishandling of much of S. W.’s writing, see Elizabeth Hart, “Susanna and Her Editors” PWHS 48.6 (1992): 202–209; and 49.1 (1993): 1–10.

3. Now that we have a Foucauldian reading of John Wesley, Henry Abelove’s Evangelist of Desire (Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press, 1990), and given the plethora of feminist literary historical work, there are doubtless many critical approaches that might be applied to S. W’s texts. I have noted in an as yet unpublished paper that, for some, a devotional discipline might provide the private space Virginia Woolf advocated for a woman to write and think: “The Prayer Closet as ‘A Room of One’s Own’: Two Anglican Women Devotional Writers at the turn of the Eighteenth Century”; an earlier version was presented under a slightly different title at the American Society of Church History meetings, Washington, D.C., December 1992. See Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (London: Triad Grafton, 1977).

4. W Reginald Ward and Richard P. Heitzenrater, eds., The Works of John Wesley: Vol. 19. Journals and Diaries, II (1738–42) (Nashville: Abingdon, 1990), p. 283. For a discussion of this and other details of the Annesley family, see the authoritative study by Betty Young, “Sources for the Annesley Family,” PWHS 4S.2 (1985): 47–57.

5. Sometimes written 1668/69 to indicate that the Old Style calendar, still in official use until 1752, did not begin the new year until March 25.

6. John Dunton, The Life and Errors of John Dunton, 2 vols. (London: J. Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1818), 1:166.

7. Timothy Rogers, The Character of a Good Woman… Occasion’d by the Decease of Mrs. Elizabeth Dunton…(London: John Harris, 1697). Filtered through the lens of a Nonconformist minister, the sermon shows numerous parallels between Elizabeth and her younger sister Susanna. Like Susanna, she kept a diary, and in it she “made a great many Reflections, both on the State of her own Soul, and on other Things, that as far as could be judged by the Bulk, would have made a very considerable Folio” (sig. e5).

8. Young, “Sources for the Annesley Family,” pp. 55–56.

9. See John A. Newton, “Samuel Annesley (1620 1696),” PWHS 45.2 (1985): 29–45.

10. The house, a plain three-story brick structure with an attic garret just off Bishopsgate, is called “Susannah [sic] Wesley House” and most recently served as a solicitor’s office. It is dwarfed by the current spate of office-block developments above and around Liverpool Street Station, but the site is apparently noteworthy enough to have survived destruction and redevelopment. However, it has recently been flanked on the Bishopsgate side by an American-style “Fatboy’s Diner.” A plaque on the north side commemorates Susanna Annesley’s birth. For a sense of Samuel Annesley’s extensive library, see the sale catalogue prepared after his death, in Edward Millington, ed., Bibliolheca Annesleiana:… The Library of the Reverend Samuel Annesley, … (London, 1697). An original is in the British Library; Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, D.C., owns a microfiche copy.

11. The Character of the Late Dr. Samuel Annesley, by Way of Elegy … by One of His Hearers (London: E. Whitlock, 1697).

12. Newton, “Samuel Annesley,” p. 39.

13. See the letter to Samuel Wesley Jr., 11 October 1709.

14. The most authoritative, recent account of Samuel Wesley’s early years, based on newly discovered materials, is H. A. Beecham, “Samuel Wesley Senior: New Biographical Evidence,” Renaissance and Modern Studies 7 (1963): 78–109.

15. Ibid., pp. 85–87. See also Newton, Susanna Wesley, pp. 65–66.

16. For instance, discussions with her future husband seem to have persuaded her to pull back from a temporary inclination toward Socinianism (Unitarianism). See Newton, Susanna Wesley, p. 66.

17. Lawrence Stone, The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500–1800, abridged ed. (New York: Harper Colophon, 1979), pp. 217–253.

18. At the time a semirural suburb, Newington Butts is now inner city, a stone’s throw from Elephant and Castle underground station. The parish church is long since gone, and the only ecclesiastical edifice is Spurgeon’s London Tabernacle, relic of a later time, itself seeming out of place in the tangle of council flats, shopping centers, and speeding traffic.

19. See his long letter of 22 August 1692, in Beecham, “Samuel Wesley,” pp. 102–108.

20. Ibid., p. 108.

21. Clarke, Wesley Family, p. 61.

22. For details on the Wesley offspring, see Frank Baker, “Investigating Wesley Family Traditions,” Methodist History 26.3 (1988): 159–162.

23. See especially Clarke, Wesley Family.

24. Letter to Samuel Annesley Jr., 20 January 1721/22, in part I of this volume.

25. See Young, “Sources for the Annesley Family,” p. 52.

26. See, among others, her letter regarding the 1709 fire to Joseph Hoole, 24 August 1709. Even at the end of her life, she was not in good financial shape. See the letter to Charles Wesley, 19 October 1738. For Samuel Wesley’s perspective, see Clarke, Wesley Family, pp. 76–82, 86–96, and 128–133, and Beecham’s publication of a recently discovered letter from the South Ormsby period, in “Samuel Wesley,” pp. 102–108. A letter from Emilia to John, 7 April 1725, details the pinch she felt when called home from her boarding school job to keep her mother company (George Stevenson, Memorials of the Wesley Family … (London: S. W Partridge; New York: Nelson and Phillips, 1876), pp. 262–64.

27. See journal entry 119, dated 17 October 1715, in part II of this volume.

28. Beecham, “Samuel Wesley,” p. 108.

29. See the following letters: 27 November 1707; 14 February 1708/09; 20 January 1721/22; 10 September 1724; 23 February 1724/25; 26 July 1727; 12 August 1728; 11 August 1729; 21 February 1731/32; 5 August 1737; 6 December 1738.

30. See journal entries 105 and 13, respectively. See also entries 25, 160, and 253 and her letter to her son John, 26 July 1727.

31. Letter to Samuel Wesley Jr., 11 October 1709.

32. See “On Educating My Family,” the first essay in part III of this volume.

33. See the brief introduction to ibid.

34. The family story told to Adam Clarke by John Wesley was that Samuel Jr. did not speak at all until he was between four and five years old. One day when the family could not find him, S. W. combed the house, frantically calling his name. Suddenly, a small voice was heard speaking a complete sentence from under a table: “Here am I, mother!” Looking down they found “Sammy” and his favorite cat. “From this time,” says Wesley, “he spoke regularly, and without any kind of hesitation.” Clarke, Wesley Family, pp. 213–214.

35. Susanna Wesley, pp. 109–110.

36. See journal entry 79 and the letter to her husband, 6 February 1712.

37. Note the insistence of Richard Allestree’s influential The Whole Duty of Man …(Oxford: George Pawlet, 1684), p. 115, that after children are “past the age of education,” parents are still to observe them “and accordingly to exhort, incourage, or reprove, as they find occasion.”

38. S. W’s concern for her children’s marriages, particularly her daughters’, is visible in several letters to John, for example, 12 October 1726 (on Hetty’s problematic relationship), 1 January 1733/34 (her reservations on Molly’s marriage), and 31 January 1727 (some straight talk on what she regarded as an inappropriate, albeit platonic, relationship of his own). Her dissatisfaction with her daughter Suky’s choice is recorded in her letter to her brother Samuel Annesley Jr., 20 January 1721/22. The same letter indicates that at least one of the sisters tried for a while the only other option, that of governess or teacher. The bad luck of the Wesley daughters in later life is the subject of Frederick E. Maser, The Story of John Wesley’s Sisters, or Seven Sisters in Search of Love (Rutland, Vt.: Academy Books, 1988).

39. The Methodist nickname came later, one of several slung at the devotional group the Wesley brothers led at Oxford, but the way of life, in both its well-ordered and obsessive-compulsive aspects, clearly originated in the Epworth rectory. John Wesley understood the importance of his mother’s childrearing and educational methodology and gave wide circulation to her letter describing it. For its continuing influence, see the introduction to “On Educating My Family,” in part III of this volume.

40. Family letters started the legend, including S. W’s own to Samuel Jr., 14 February and 11 October 1709, and one to the Rev. Joseph Hoole, 24 August 1709.

41. See the convenient summary of these sad episodes in Maldwyn Edwards, Family Circle: A Study of the Epworth Household in Relation to John and Charles Wesley (London: Epworth, 1949), pp. 18–20. The baby was “overlaid” by the nurse to whom it was entrusted the night before the election. Noisy partisans had kept her awake by discharging pistols and making a general disturbance where she and the Wesleys were lodged for the night in Lincoln; when she finally fell into a deep sleep, she unknowingly rolled over on the infant and smothered him. See the account in Samuel Wesley’s letter to the archbishop of York in Clarke, Wesley Family, p. 90

42. To Samuel Wesley Jr., 11 October 1709. See also the various journal entries in which she wrestles with this issue, for example, 51, 52, and 56, and the opening lines of her letter to Suky on the Creed, in part III of this volume, as well as the journal entry 2, in part II, which alludes to the “misfortunes that have separated” the family.

43. Gordon Rupp, Religion in England, 1688–1791 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), p. 6, explains that there were “recurring problems of conscience” for some half a century for those who refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the new succession. Clearly the abortive attempts to return the Stuarts to power in 1715 and 1745 provoked such soul-searching; but so did the death of a monarch, whether the deposed James II or the actually reigning William, Anne, and George I.

44. This bit of family oral tradition was recorded by Clarke, Wesley Family, p. 83.

45. See Rupp’s helpful chapter on the phenomenon in Religion in England, pp. 5–28.

46. Quoted in Robert Walmsley “John Wesley’s Parents: Quarrel and Reconciliation,” PWHS 24.3 (1953): 55. Walmsley first discovered and published S. W’s letters to Lady Yarborough and Dean Hickes.

47. To Samuel Wesley Sr., 6 February 1711/12.

48. To Samuel Wesley Sr., 25 February 1711/12.

49. Ward and Heitzenrater, Journals and Diaries (30 July 1742), p. 284.

50. Harry Price, Poltergeist over England, quoted in Edwards, Family Circle, p. 95.

51. Joseph Priestley, Original Letters, by the Rev. John Wesley and his friends … (Birmingham: Thomas Pearson, 1791), p. iv.

52. Clarke, Wesley Family, p. 143.

53. Ibid., p. 154. Beliefs and practices of this sort were certainly part of the popular religious mix of the time. James Obelkevich has detailed their existence in nineteenth-century Lincolnsire (though in another part of the county) in Religion and Rural Society: South Lindsey, 1825–1875 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976): pp. 259–312. He finds belief in ghosts, witches, and wise men—who could in some ways be seen as rivals to the clergy—among village people (pp. 282–291) and accounts for it in part by the weaknesses of official Christianity, “the remoteness of its high God, the social elevation of its clergy,” and so on (p. 301). However, “wise men rushed in where Anglicans feared to tread …” (p. 304), dealing with everyday problems concerning weather, crops, animals, health, love, and death in immediate ways. In the Epworth case a century before, members of the Wesley family found themselves, against their natural Enlightened inclinations, pulled into the popular worldview. Their fascination is evident, but so is their discomfort; they were very much in Epworth but not of it, and that distinction may at some level help explain the whole episode.

54. See her letters to Samuel Jr.—12 January 1716/17; 25 or 27 January 1716/17; and 27 March 1717—and her “Account to Jack,” dated 27 August 1726, which I have included immediately thereafter, in part I. The fullest collection of all the material on Old Jeffrey is in Clarke, Wesley Family, pp. 136–167.

55. See entries 84, 131, 133–135, 138–139, and 207. The quotation is from the modern edition, Pascals Pensees, introducton by T. S. Eliot (New York: Dutton, 1958), p. 78.

56. Though we should not conclude that she lacked friends in earlier stages of her life just because few nonfamily letters survive from those periods.

57. To Alice Peard, 5 August 1737; to the countess of Huntingdon, 1 July 1741.

58. An objectionable woman seems to have attempted to cozy up to S. W at the Foundery, driving off other, more compatible companions. See the letter to Charles, 27 December 1739.

59. To Charles Wesley, 27 December 1739.

60. See Ward and Heitzenrater, Journals and Diaries, II. (3 September 1739), pp. 93–94. Hall later turned out to be, in Clarke’s words, “a Moravian and Quietist, an Antinomian, a Deist, if not an Atheist, and a Polygamist, which last he defended in his teaching, and illustrated by his practice” (Wesley Family, p. 421). Charles celebrated her newfound “assurance” in a poem composed for her tombstone, making it appear as if she had lived in darkness, evangelically speaking, for the previous 70 years. See Ward and Heitzenrater, Journals and Diaries, II (1 August 1742), pp. 283–284.

61. To Charles Wesley, 6 December 1738.

62. See Clarke, Wesley Family, pp. 275–286, refuting the claim made by Samuel Badcock in 1782 and afterward circulated for purposes of controversy that Mrs. Wesley “lived long enough to deplore the extravagances of her two sons John and Charles.…”

63. Ibid., p. 236.

64. Ward and Heitzenrater, Journals and Diaries, II, pp. 282–84. The original tombstone was notable for its lack of biographical information and its inclusion of a four-stanza hymn composed by Charles Wesley:

Here lies the body of Mrs. Susanna Wesley, the youngest and last surviving daughter of Dr. Samuel Annesley

In sure and steadfast hope to rise

And claim her mansion in the skies,

A Christian here her flesh laid down,

The cross exchanging for a crown.

True daughter of affliction she,

Inured to pain and misery,

Mourned a long night of grief and fears,

A legal night of seventy years.

The Father then revealed the Son,

Him in the broken bread made known.

She knew and felt her sins forgiven,

And found the earnest of her heaven.

Meet for the fellowship above,

She heard the call, “Arise, my love.”

“I come,” her dying looks replied,

And lamb-like, as her Lord, she died.

Having worn badly, this stone was replaced by a more descriptive one in 1828, maintained by Methodist pilgrims ever since. A larger monument was erected on the grounds of Wesley’s Chapel in 1870. See Stevenson, Memorials, pp. 228–229.

65. Clarke, Wesley Family, pp. 291–292; his emphasis. See Proverbs 31:29.

66. Gordon Rupp, “A Devotion of Rapture in English Puritanism,” in R. Buick Knox, ed., Reformation, Conformity and Dissent: Essays in Honour of Geoffrey Nuttall (London: Epworth, 1977), p. 119. I have enlarged on this in my article “Susanna Wesley’s Spirituality: The Freedom of a Christian Women,” Methodist History 22.3 (1984): 168.

67. See the host of journal entries that quote Lucas and/or discuss Christian perfection: 193–196, 202–203, 205, 208, 212–214, 219, 226, 228, 231–233, 237–238, 240–243, and 252.

68. Wallace, “Susanna Wesley’s Spirituality,” p. 160.

69. See Charles Wallace Jr., “‘Some Stated Employment of Your Mind’: Reading, Writing, and Religion in the Life of Susanna Wesley,” Church History 58 (1989): pp. 354–366.

70. See her journal entries 181 (following Bishop Beveridge’s sermon on conscience), 51, and 191. Patricia Crawford has recently sketched the wider landscape, even including S. W (and her conscientious refusal to say “amen” to the prayer for King William) as one of the details in the picture: “Public Duty, Conscience, and Women in Early Modern England,” in John Morrill, Paul Slack, and Daniel Woolf, eds., Public Duty and Private Conscience in Seventeenth-Century England: Essays Presented to G. E. Aylmer (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993): pp. 57–76. Her conclusion is that conscience “justified some women’s wifely disobedience and their participation in English social and political life” (p.76).

71. Checking some of the important anthologies on women and Christianity, I find significant gaps that further study of S. W could help fill. There is no chapter on women of her generation or on early female Methodists in Rosemary Ruether and Eleanor McLaughlin, eds., Women of Spirit: Female Leadership in the Jewish and Christian Traditions (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972). Elizabeth Clark and Herbert Richardson’s anthology, Women and Religion: A Feminist Sourcebook of Christian Thought (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), moves from John Milton to Ann Lee to Schleiermacher with not a look at anything Anglican or Methodist. Dale Johnson’s anthology, Women in English Religion, 1700–1925 (New York and Toronto: Edwin Mellen, 1983) is better, including in its narrower focus both Anglican and Methodist sources and referring to S. W as part of an introduction to the evangelical revival; but it includes nothing of her writing. Richard L. Greaves, ed., Triumph over Silence: Women in Protestant History (Westport, Conn., and London: Greenwood, 1985), skips directly from a chapter on sectarian women in late-seventeenth-century England to chapters on Puritanism and Methodism, respectively—in America. Barbara J. MacHaffie, Her Story: Women in Christian Tradition (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1986), moves directly from the Reformation to religion in the American colonies, giving only the briefest of details about any Englishwomen in the interim. The recent collection, Lynda L. Coon, Katherine J. Haldane, and Elisabeth W Sommer, eds., That Gentle Strength: Historical Perspectives on Women in Christianity (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1990): totally neglects English religion prior to the Victorian era. And W J. Sheils and Diana Wood, eds., Women in the Church: Papers Read at the 1989 Summer Meeting and the 1990 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990), provide no direct treatment of the Church of England between the Reformation and the Victorian era. As one might expect, Methodist denominational history has done better. Witness, for example, and just to mention book-length treatment, Earl Kent Brown, The Women of Mr. Wesley’s Methodism (New York and Toronto: Edwin Mellen, 1983); Paul W Chilcote, John Wesley and the Women Preachers of Early Methodism (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow, 1991); and of course, John Newton’s Susanna Wesley and Rebecca Lamar Harmon’s Susanna: Mother of the Weskys (Nashville and New York: Abingdon, 1986).