Immigration patterns in this decade were greatly affected by the 1929 stock market crash and the resulting Great Depression. In addition, quota-law restrictions, first enacted in 1921, finally took full effect. For immigrants in foreign countries seeking visas, this meant that immigration processing was now slowly shifted to US consulates abroad, thus turning them into mini–Ellis Islands. While the US population reached 125 million in 1930, for the remainder of the decade it would only see seven hundred thousand new immigrants arrive, the lowest number since the 1830s. Many of the immigrants who came were Jews fleeing the persecution of Nazi Germany and Hitler's mounting war machine. At home, Americans were hurting economically, as one in four workers were unemployed and many families went hungry. Deporting illegals now became a viable solution as a nation built on growth turned to subtraction to help solve its problems.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

|

Anti-immigrant campaign begins as the US government sponsors a Mexican repatriation program intended to encourage people to voluntarily move to Mexico, but thousands are deported against their will; more than four hundred thousand Mexicans, both illegal aliens and legal Mexican Americans, are pressured through raids and job denial to leave the United States, many of them children who were US citizens—a similar situation faced today by DREAM Act students (see chapter 12, page 329). |

1932: 1932: |

Hitler's antisemitic campaign begins, as Jewish refugees begin fleeing Nazi Germany to the United States and other nations. |

|

Hitler becomes German chancellor; Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany come to the United States, though barriers imposed by the quota system are not lifted. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) is formed by a merger of the Bureau of Immigration and the Bureau of Naturalization. |

|

The Tydings-McDuffie Act, also known as the Philippine Independence Act, is approved by Congress and strips Filipinos of their status as US nationals and restricts Filipino immigration to an annual quota of fifty. |

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1930s: 700,000

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Canada and Newfoundland (162,703), Germany (119,107), Italy (85,053), United Kingdom (61,813), Mexico (32,709), Ireland (28,195), Poland (25,555), Czechoslovakia (17,757), France (13,761), Cuba (10,641)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade (not all through Ellis Island), and who would later become famous, include:

Sidor Belarsky, Russia, 1930, singer/composer

Primo “The Ambling Alp” Carnera, Italy, 1930, heavyweight boxer

Lin Yutang, China, 1931, writer

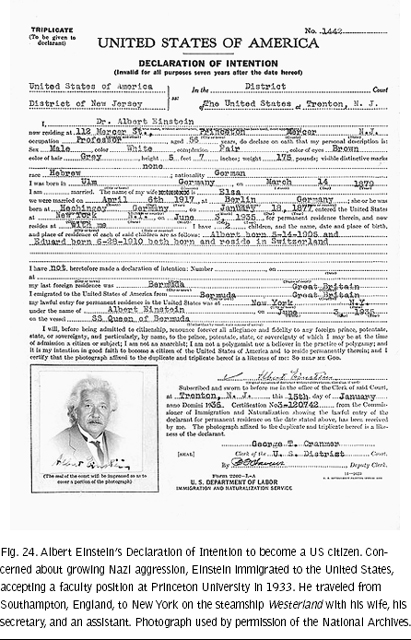

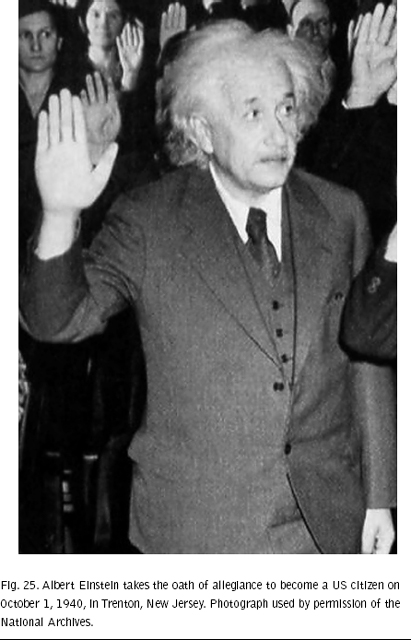

Albert Einstein, Germany, 1933, physicist

Billy Wilder, Austria, 1933, film director

Jack “The Gorgeous Gael” Doyle, Ireland, 1934, boxer/actor

Nigel Bruce, England, 1934, actor (“Dr. Watson”)

Ieoh Ming (I. M.) Pei, China, 1935, architect

Desi Arnaz, Cuba, 1935, bandleader

Hans Bethe, Germany, 1935, Nobel laureate in physics

Edward Teller, Hungary, 1935, nuclear physicist (“father of the hydrogen bomb”)

Wenceslao Moreno (“Senor Wences”), Spain, 1936, ventriloquist

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, India, 1937, astrophysicist

Dick Haymes, Argentina, 1937, singer

Pauline Trigére, France, 1937, fashion designer

Georg and Maria von Trapp and family, Austria, 1938, singers

Henry Kissinger, Germany, 1938, political scientist/diplomat

Enrico Fermi, Italy, 1938, nuclear physicist and Nobel laureate

Lucien Aigner, Hungary/France, 1939, photojournalist

Richard Krebs (“Jan Valtin”), Germany, 1939, spy

Elizabeth Taylor, England, 1939, actress

Mike Nichols, Germany, 1939, film director

Thomas Mann, Germany, 1939, writer

André Previn, Germany, 1939, pianist/conductor/composer

Anne Elisabeth Jane “Liz” Claiborne, Belgium, 1939, fashion designer

She came to America during the Depression from Renazzo, thirty miles north of Bologna. Her father was a stonemason who helped build the subways, highways, and bridges of New York City. Her family settled on Long Island. She had three children and five grandchildren and celebrated her fiftieth wedding anniversary with her husband, George, in Hawaii. “I'm very proud to be interviewed by you,” she said. “I would like to dedicate this in loving memory of my mother and father, Albano and Argia Ardizzoni Nieri, for the sacrifice they made to give us a better life in the United States.”

We lived in a courtyard on a farm. My father had come here in 1923. A friend of his had come to the United States and kept after my father to come here. He became a foreman in a brick-making factory. I remember when he left. My mother was very sad; we were all crying. She was left there, twenty-six years old with three small children: one at ten months old, I was four, and my other brother was three.

I couldn't quite grasp the reason. I knew that he was going to America. And although my grandparents on both sides of the family didn't live very far, we were still isolated. My grandparents were tenant farmers, and they couldn't take off any time they wanted. They had a horse and buggy, and once in a blue moon they'd come to visit. Fortunately, the other tenant family that lived in the same courtyard with us was very friendly with Mom, and they kept her company and so on because we just couldn't do any traveling.

So we lived on this farm, and you can imagine my mother being very sad because we had no money. Pop had to borrow the money from my mother's father to come here. It was October, just the beginning of the winter setting in. Fortunately, all the supplies had been already bought and provisions made for the winter. We had to do that because we had no form of transportation whatsoever. Mom had my father's bicycle. We had a lot of snow. Renazzo is about the same latitude as New York and Long Island, so we had very severe winters.

We went to school from eight in the morning till two in the afternoon, and then from two to five we'd go to the nuns, the Catholic school, to learn religion, and to learn our prayers, which were taught to us all in Latin, and the masses. During summer vacations, my mother kept us in the Catholic school. We lived right near the church. And the nuns would teach the girls mending, crocheting, knitting, a little cooking.

The boys were taught, besides religion, farming and a little carpentry, which came very handy later on in life. The nuns were very strict with us. There was a boy sitting behind me in class and he was pulling my hair, so I turned around to tell him to stop, and the nun came and she gave me a whack across the face. But it was OK because everybody else got treated the same way.

The first year I went to school, I had never been apart from my mother and my brothers, and I just didn't want to go to school. So I didn't pay any attention to the teacher, and I would be put in the corner. Every day I wanted to be home with my baby brother and my other brother. I was a little mommy to them because Mom used to work on the farm whenever she could to earn extra money. We raised corn, wheat, hemp.

Our house, I went to see it in 1973. It was still there, but now it was a little store because it sat on the main road that led into town. We had four rooms, the downstairs kitchen and fireplace—that was our heat—and a utility room with a dirt floor. The second floor had one big bedroom and a smaller one where we put our winter supplies, the corn and wheat and everything, because we had to get all that stuff in before winter set in.

We had no glass windows, just shutters, wooden shutters, and you could put your finger through the cracks in them. So upstairs Mom would have to put rags in the cracks so we wouldn't get snow or rain in. Downstairs, Mother used a certain kind of brown paper to glue on to the windows and then put oil on the paper so it would be somewhat translucent to let light in. And if we forgot to put up the paper before a rainstorm or a heavy wind, the glue—which was made with flour and water—would tear up and we'd have to do it all over again.

When it was really cold, the well would freeze in the courtyard. There was no pump. We'd drop a pail down and bring the water up. We had a water pail in the kitchen. So we used to melt snow and use that for cooking and for drinking. It wasn't polluted like it is today.

We had a little box which held about six chickens, but we kept them upstairs on the second floor so they wouldn't be stolen or the eggs stolen. We had no property, just this little house that we rented from the farmer. I remember the chickens would walk up the rickety stairs to the second floor. Little rickety stairs about six inches wide, and to train them to go up there, when we got a new batch of chickens, we would put corn feed upstairs and they'd learn. To make them come down, Mama would call them in the morning and put the corn on the ground, and they would come. After three or four days they did it automatically.

We had delicious brown watermelon, and sometimes that would be our supper. Our meals were very simple. We had our own eggs, so we ate eggs all the time. We'd take a sack of wheat and go down to the mill and have it ground into flour. We had cornmeal, from which we made polenta. And we made it in many different ways. Our staples for the winter were beans and rice. We never had any vegetables. Even in summertime, the only vegetables we raised were celery, lettuce, and peppers, which we dunked in olive oil. We had a nanny goat for milk. We drank very little milk. We didn't drink milk like we do here. I can remember when the nanny goat had babies they would jump on my mother's back, stomp on her back, while she was milking the goat.

For holidays, Mama's specialty was tortellini or cappelletti, little dumplings filled with meat. Now they make them with all kinds of fillings, but we made them with meat and then cooked them in chicken broth. It was a family affair. We'd all help Mom to make it. I remember standing on a little stool trying to make the homemade noodles and I couldn't reach the table.

My mother was a very loving but stern mother. If my baby brothers got into trouble, I got a spanking because it was up to me to keep them out of trouble. She was the oldest in her family, a family of seven. She had to help with her [mother's] children, so that's the way she brought me up. So I have nothing but praise for my mother. She never left us alone.

In the fall, there were a lot of festivals and feasts in honor of the patron saints. Fireworks at night, flea markets, games of chance, loads of food, and all the young ladies would have their dates. We had two of them living in the next-door tenant house with us. They used to come in and wait for their boyfriends, and they would meet at our house and then change into better shoes. They'd come with their old working shoes through the small streets all full of mud, and then change. They used to play with us children. I have very pleasant memories.

I can remember having these big racks with trays of silkworms. Hundreds of silkworms. And you think a worm is quiet? When they're feeding, what a humming sound they made! Mom would climb the mulberry trees early in the spring, when the leaves were nice and tender, to feed these worms. We would have them until they went into the cocoon stage. We would raise them in our homes. I presume my mother got paid for taking care of them. Then the farmer would take them and send them to be processed for silk.

We had no candy. When we wanted candy, Mom would say, “What do you want with candy? This is no good. When we get to America, Dad has a big bag of candy for you.” We were so disappointed when we got here. [She laughs.]

When my father left, he told my mother that as soon as he could, he would send for her. However, after he got here, the law was changed in 1924, and he had to become a citizen. So he went to night school and learned the history of the United States, and in 1929 he got his citizenship papers and he sent for us.

We came here August 13, 1929. From our little town, we had to go to the railroad station in Ferrara. We left about four o'clock in the morning. My grandfather came with his wagon where we put our trunks in. Pop had told Mom to bring her feather mattresses because here they only had mattresses with corn husks and they were uncomfortable.

We took the train to Genoa. That took eight or nine hours, and we were exhausted. We went to the hotel. We had a guide with us because Mom was afraid to go by herself. She'd never been away from Renazzo. So we had a tour guide from the travel agency accompany us to Genoa.

The next day we had our papers checked. A doctor examined us all, although we had been examined at home and we were all OK, and then we were reexamined [on the boat]. They told my mother that she'd have to bathe us. We fiddled with the faucets. We didn't know what the faucets were for, only that we saw this thing dripping. So we fiddled until the water came out. Mama says, “How am I going to give you a bath? The water keeps going down in the hole there!”

We were fourteen days on the boat. We were in a cabin, the four of us. At night, the steward, a woman, would come around with evaporated milk. “You must drink it,” she said. “This is good for you.” But we didn't drink it because we didn't like it. Mama was always so afraid that we would fall overboard. We always had to stay by her skirt. So we didn't explore the ship at all. We'd go up on deck, and she'd hang on to us for dear life.

The night before we arrived, they told us if we wanted to see the statue we'd have to get up early in the morning. We were up at four o'clock. We went up on deck, and everybody was up. And, oh, my God, when she came into sight I got gooseflesh, and to this day, I've been out there six or seven times. The last time was a year and a half ago. I took some cousins of mine who came from Italy. We went to Ellis Island, and I still get gooseflesh. I love that lady. She's beautiful.

When we came in, we saw my father down on the docks. We recognized him. Then we went into the big hall, and it was all brown and dreary, and everybody was crying. We were like sheep in there, all so crowded. My mother started to cry because she was sure my father wouldn't find us. We were examined again. I read where some people had terrible experiences. But they just looked in our hair, our teeth, our eyes, and that was it. It took about four or five hours before we got out of there.

My father tried to grab all of us. He was a big man, all right, and hugged us and kissed us. He was so happy we were here. Then he took us home.

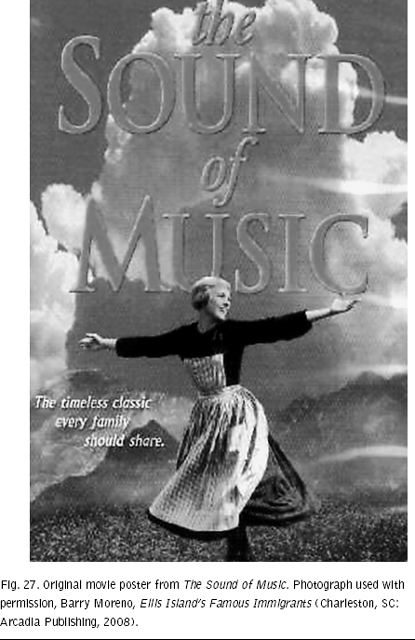

She was part of the world-renowned Trapp Family Singers, who inspired the 1959 hit Broadway musical and the 1965 Academy Award Best Picture winner The Sound of Music. She was the second-oldest daughter of Baron Georg von Trapp and Agathe Whitehead von Trapp, who had seven children. When Agathe died in 1922 from pneumonia, the forty-seven-year-old Baron (portrayed in the movie by Christopher Plummer) remarried in 1927 to twenty-two-year-old Maria Augusta von Trapp (portrayed in the movie by Julie Andrews). Maria Franziska sang second soprano in the choir but spent most of her adult life in Papua New Guinea as a missionary. Besides her elder sister Agathe, she is the last of the original seven von Trapp children. “In the movie, I was Louisa,” said Maria, who was ninety-six years old at the time. “I was the third one. I had brown hair.”

I had two mothers. My birth mother died of pneumonia in 1922. I was eight years old. My [birth] mother, she was not religious. I remember when she was very sick she asked my father, “Where will I go when I die?” She had no knowledge about eternity or anything.

My second mother, my stepmother, her name was also Maria—we were not close, sometimes maybe. [She makes a face and smiles.] She was a very strong, a difficult person. My second mother was religious. My father, Georg, was very kind. He was a Protestant. When he remarried to Maria, she wanted to raise the kids Catholic. So when we were growing up, we were told not to talk about religion with our father. So we're not really Catholic. Am I Protestant? I don't know what I am. [She laughs.] I'm a believer, I guess. I'm just a child of God….

In Austria growing up I remember the Nazis. They were scary—not a nice memory…. We didn't have Austrian passports. We had Italian passports, and so the Nazis couldn't do anything. They couldn't touch us. Hitler and Mussolini were aligned—but because we had Italian passports we could leave. We didn't have to sneak out of Austria and over the mountains like it showed in the movie. Also, we had a contract to sing here in America. They wanted us to come here for concerts for six months, and while we were away the Nazis came and took over our home. Many years later I went back to Austria, to the house, and it's still there. It's now a bed-and-breakfast hotel, very nice.

When we left Austria I remember we went by train to Italy and took the boat to America from Genoa. We came to this country on the boat, the American Farmer. Funny, in the end we became farmers, we became American farmers. [She laughs.] The boat sailed to New York. Upon arriving I remember being amazed at all the skyscrapers—they seemed to rise out of nothing. It was the first time for me. Seeing such a thing…. Later we went back to Europe, to Scandinavia. We toured, we sang.

Then the second time we came to America we waited for the boat from England, from Southampton, and we came back to New York. We were detained at Ellis Island for one or two days. I was 25 at the time. We went to the Big Hall [Registry Room]. They separated the men from the women. I remember babies crying…. Once in New York we stayed at the Wellington, Hotel Wellington. We came to do a concert north of New York, I don't remember where….

Then, in the 1960s, I went to Papua New Guinea as a missionary. Actually, I wanted to go to Africa, but we were in Australia at the time. There were missionaries there, and then we went to New Guinea. I went all by myself. I was all alone. I was a teacher. I taught [she gestures with her hands] everything! [Broad smile.] I taught elementary school students—but they knew more than me! [She laughs, then becomes serious.] I loved it there. I was there for thirty years! Very few visitors. I think my stepmother came once or twice in that time. I was very happy there.

Before I left New Guinea, I adopted a boy. He's from Africa. He's black. He lives here [in Vermont] with me. I adopted him several years ago. I met him in New Guinea. He had nothing to eat…. Our bond is our faith in God. I don't go to church. I'm too old. My church is here, my home. I pray with Kakooly, who I adopted [now in his fifties], my adopted son. We pray together. We pray at home…. I was never married. I never found anyone. God didn't bring me anybody—so I never had children, although I had plenty of nieces and nephews. More than enough! [She laughs.] But I'm happy with that. I'm not angry with God. Anyway, I feel uncomfortable about marriage. It's a risk, you know? My younger brother Werner, he was born after me. [She points to a picture of him on the wall.] We were very close. Then he got married and they went away, his wife took him away. I'm sure when I meet God he's not going to ask, “Why didn't you get married?” [She laughs.]

So why did I come back? [She pauses again.] The Lord called me back. That was about fifteen years ago I came back to America. I would have stayed in New Guinea. That was the happiest time of my life. I did not know what it was going to be like before I went, but [pauses] it was paradise! [She smiles with joy.] I had friends there. We had such wonderful times in Port Moresby [capital of Papua New Guinea and its largest city]. I don't know why the Lord called me back. I'm not sure why, but he did. I would still be there, even though the life in New Guinea can be very hard and it became very dangerous at the end of my time there. I would still go back there, but I'm too old now….

I'm surprised by the popularity of The Sound of Music. People still talk about it. They watch it in Russia and Japan. I think people love it because it's a good story, but mostly because the children are in it…. I met the actors in the movie, but Julie Andrews—she didn't want anything to do with us. I think she didn't like my [step]mother. They didn't get along. The children actors in the movie, they came here recently [2008] for a reunion. But Julie Andrews didn't come or Christopher Plummer. I never met them. They were both invited, but they didn't show up. [She pauses, looks straight away.] I'm glad we came here. I'm glad we came to the United States. But it would be nice to go back to New Guinea. I was happy there.

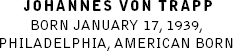

His mother, Baroness Maria Augusta von Trapp, was pregnant with Johannes when the von Trapp family came by boat to America for the second time in September 1938. They were detained at Ellis Island for several days after his mother exclaimed to an immigration inspector, “I'm so glad to be back, I never want to leave again!” Johannes was one of three children born to Maria, played by actress Julie Andrews in the movie The Sound of Music, and his father Georg, “The Captain,” played by actor Christopher Plummer. Georg had seven children from his previous marriage, ten in all. The family sang and toured extensively until they performed their last concert in New Hampshire in 1956. They settled in Vermont, opening a twenty-seven-room Austrian-style ski lodge on 2,400 acres in Stowe, run by their mother, in 1950. Although trained as a forest ecologist, Johannes found himself pressed into service to help his mother run the lodge. In December 1980, a tragic fire forced forty-five people, including his mother, to flee in their nightclothes, leaving behind the body of a thirty-year-old Illinois man, who was later found in the rubble. The Trapp Family Lodge was rebuilt. When his mother died in 1987, America's most famous immigrant family endured internal turmoil of their own involving lawsuits over stock, with Johannes eventually buying out thirty-two family members in 1994. Today, his son, Sam von Trapp, manages the lodge, with Johannes's goal to completely turn over the reins to him one day so he can travel and hunt and ranch, his passions. “As I get older, I realize that life is not a dress rehearsal,” said Johannes. “You've got to do it and enjoy it while it's happening, because we don't get to do it again.”

I was born January 17, 1939. We came over in September 1938 into New York Harbor. We came to New York by ship. The first time we came, we took the train from Salzburg to Genoa, Italy, and took the boat the American Farmer. For our first visit we were perfectly legal, and so there was no reason to send us to Ellis Island because we came as “visiting artists.” I was born a few months after we arrived. Then we traveled, performed, sang. We were living in Philadelphia. The following June, when I was five months old, our visas were not renewed, and we had to go back to Europe. So we spent the summer in Denmark and Sweden. We couldn't go back to Austria, obviously, because of the war, and Sweden had been very welcoming to my family earlier when they had a concert tour there. Sweden was officially neutral, but it had certain Nazi sympathies, and we were not all that welcome.

We finally got the visas straightened out, and we returned to the United States on the Bergensfjord, the Norwegian ship. We had spent the summer in Scandinavia and came to New York, but when my mother spoke to the immigration officer on board the boat in New York Harbor, he asked, “How long do you plan to stay?” and my mother said, “I'm so glad to be back, I never want to leave again!” which is not the right thing to say to an immigration inspector, so he sent us to Ellis Island, and we spent several days there.

My mother was a very strong-willed person. She was much more complex than her film portrayal in The Sound of Music. She had an unhappy childhood, and that kind of childhood either makes you very strong or you end up homeless somewhere. And she ended up very strong. She had a really fine mind. She had a gift for languages. She had incredible charm when she chose to exercise it. Great persuasive powers. She loved being outdoors. She loved to walk and exercise. After a childhood in which she was not at all religious, my mother underwent a conversion and became very religious, I would say to a fault, too much, but that's just my opinion. She wasn't a fundamentalist; she didn't claim that everything written in the Bible happened the way it was written. But her life was built around what she felt God wanted of her. [He smiles.] I once said as a kid in an argument with her, “Your will or God,” implying that it was her choice, not God's, and there was that element too, you know. But we got along very well. I was raised as a Catholic. Religion was an important part of her life, but it wasn't everything. I mean, she loved music, history, art, all sorts of things. She really had a great appreciation for Western culture and enjoyed life tremendously.

I was eight years old when my father died in 1948. He was a much warmer person than he was portrayed in the film. I have lots of good memories of him. He drove very fast, I remember that. He was just a really kind, strong figure. But he lost his fortune [inherited mostly from his first wife, Agathe Whitehead von Trapp] and got depressed over it. I think my father was not a businessman in any accepted sense. He was a leader. A natural leader. He fought in the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. The thought of sitting down and figuring margins was sort of foreign to him. But he was a fine leader, and I think the whole family really missed him when he died. There's a small cemetery on the grounds of the lodge, and he's buried here beside my mother, along with other family members. She died in 1987.

We were ten children. Agathe is the eldest. She's ninety-seven and lives in Baltimore. Maria [Franziska] will be ninety-six, and she lives here on the property in a little house about half a mile down the road. Then my sister Eleanor lives in Waitsfield, Vermont, twenty-seven miles south of here, my sister Rosemary lives in Stowe, and I live here.

Our estate in Austria was taken over by [Heinrich] Himmler [Hitler's right-hand man] after we left. It was his headquarters during the war. The estate was in the American occupation zone, so it was given back to us shortly after the war. And we decided—I say “we” even though I was very small at the time—we decided that we wanted to stay here [in America] and didn't want to go back to Austria, so it was sold by us to a religious order, and it became a seminary for many years, and now it's a bed and breakfast. I don't think Hitler had an office there, but he visited several times. There were bomb shelters built in the garden. There was a brick wall around the property with an electric fence on top.

We initially settled in Philadelphia because after one of our concerts a gentleman came backstage and introduced himself. He was a lover of baroque music and he said, “I have an empty house across the street from my own where my mother used to live and she recently passed away—would you like to live there?” He said, “It's a large enough house,” and my mother said, “Well, we probably can't afford the rent.” And he said, “No, no—the rent will be singing Bach with me once a week all day!” [He laughs.] His hobby was in translating the choral works of Bach, so we moved there and lived there, except Philadelphia in the summer is very hot, and in the fall, winter, and spring, we were traveling and performing—so it wasn't an ideal place for us.

We wound up here [Vermont] because we had been lent a house in Stowe for the summer, and while we were here, we found this hillside, and my family fell in love with the view and the feeling of space and openness. And I really think that this is one of the few places in the East where I could be happy. I feel really claustrophobic elsewhere. But here you can see twenty miles north and twenty miles south. There's a feeling of open space.

We bought this property in 1942 and moved up here and lived here and farmed the property, and my mother quickly realized that there was no way this was going to support a large family, even though we had bought two farms. The ground was too rocky and stony, and the growing season was too short, and the hills were too steep. At that time, the ski business was just getting started in Stowe. The lifts had been built, and skiing was becoming a popular activity, so when we were away singing, our rooms were rented to skiers. And that's how we got into the lodge business. We began renting rooms in 1950. It was after my father died in 1948. We hired a lady to be a caretaker. My mother was the guiding force but she didn't check people in and out. We also had a music camp down the hill.

I started singing when I was four years old. But then from seven years old on I was full-time with the family singers. Our last concert was in 1956 in New Hampshire. My brothers and sisters had gotten tired of traveling and singing. They just didn't want to do it commercially anymore. They were tired. My brother had six kids, and he didn't want to travel throughout the year. My mother would have happily gone on for another ten years, but my brothers and sisters had pretty well had it.

Most people don't know this, but I'm a forest ecologist. I studied forest ecology. I got my master's and then took two years off to straighten out the lodge business. [He sighs.] My mother, for all her tremendous energy and entrepreneurial ability, was a terrible manager and administrator, so that every person who spent thirty dollars here cost us thirty-five. And so I needed to get some things straightened out. I was going to hire a professional to run things and go back and finish my doctoral work and be a scientist, but that didn't work out. I got married, and we had children, and after a while I realized that this was going to be my career. But I was not into this at all. This is not what I wanted to do. My mother didn't want me to take over. We had a huge battle, although I sometimes wonder whether she staged all that, thinking that if I didn't fight for it I wouldn't care about it. She really had no idea how to run a business. When I took over, we had seventy-five employees, and I cut it to twenty-seven. This was 1969. There were just a lot of people here who weren't doing anything. They were here because they needed this place, not because we needed them. So I, for better or for worse, cleaned that up and we started making money! [He pauses.] It's been a challenge. It's a tough industry, and Vermont's a tough state to have a business because it has a low population base and we have to bring all our visitors up from the eastern megalopolis. But I've been able to do some fun things on the side as well. For instance, we've just launched a new line of draft lager beers with the name “Trapp Family Lodge, Stowe, Vermont.” Is the brand of the von Trapp name still strong? I think we'll find out with this beer.

It's been more than forty-five years, and people are still drawn to the movie. It's sort of a phenomenon. There are a whole bunch of different themes in it I think that resonate with people. It was, for example, not only popular in the English-speaking world—it was popular in Japan. It was extremely popular in China. Now, if you've ever expected a movie to be censored by the Chinese authorities, it would have been The Sound of Music because it highlights resistance to authority and all sorts of sensitive themes, but the film was tremendously popular in China. I think there are certain themes in it that are timeless, such as love of family, pursuing freedom, following your conscience, and doing what you like.

I met Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer. Christopher Plummer, interestingly, was here as a guest with his grandmother when he was a little boy. They came skiing and stayed in the old lodge, long before any film stuff. Actress Mary Martin and my mother had a very nice relationship. [The original Broadway production of The Sound of Music opened in November 1959, starring Mary Martin and Theodore Bikel.] They got along very well. Julie Andrews and my mother didn't get along quite as well. They respected each other, but Julie Andrews definitely wanted to do her thing and not what my mother wanted. But then, we didn't have creative control over the movie. My mother made a very bad deal a long time ago and sold our rights away. The Sound of Music company was generous enough to say, “Hey, you made a bad deal—we think you should have some participation in this,” and so they gave my mother some participation, both creatively and financially. They needn't have done that, which was very kind. I never met Robert Wise, the director, but my mother knew him quite well. My mother even went to Austria, and she was involved in the making of the film, but the rest of the family were not involved….

The greatest difference between the film and real life is first of all the time scale—my parents were married in 1927 and the film is set in 1938. So the children are all eleven years older. Another one is that the film downplays a very important personality, the priest who was our conductor, our musical director, Franz Wasner [portrayed by the character named Max Detweiler in the movie], and without him the family would have never had great success. He was a gifted conductor and arranger. He knew how to select music and arrange it so that it built on the family's strengths and minimized its weaknesses. [Arturo] Toscanini listened to one of our recordings and is supposed to have said, “They have a good conductor.” [He smiles broadly and chuckles.] Wasner returned to Austria and died there in 1992, I believe. He never became an American citizen. My family all became Americans, although my father did not. But my brothers were in the American army, and they fought their way up through Italy and drove into Salzburg three days after the war ended, wearing their American army uniforms in the jeep—it was quite an emotional feeling for them….

I'm a big-game hunter. I love to hunt. I've been to Africa a few times, traveled all over North America. I want to go to Asia. I've had ranches out west. One was in southwestern Montana, a beautiful property, about twenty-seven thousand deeded acres and another seventy-five thousand acres leased. It was a huge operation. We ran six thousand sheep and two thousand cows and it was hard work. I've never worked harder in my life. I was up at 5:30 every morning, and I hate getting up in the morning. I have trouble going to sleep in the evening. For me, the day should be thirty hours long rather than twenty-four. I had the ranch for three and a half years. But I had a property in Arizona for ten years before that and one up in British Columbia for three years before that. I'd love to get another ranch.

After my mother died in 1987, her stock in the business was widely distributed among nephews and nieces, etc., and people who had been bought out years earlier once again got stock—so suddenly we went from five stockholders before she died to thirty-two stockholders, and it just wasn't a workable thing. Everybody was pulling in different directions, and I ended up buying most of them out. Actually, I bought them all out. So I own it now with my kids, Sam and my daughter Kristina, who lives on the property in a house with her husband. But in the process, unfortunately, my ranch had to get sold, so I would like to buy another one out there….

Regrets? I was having breakfast with my son, Sam, the other morning and I thought, “This is something that I would have liked to have experienced with my father.” Just sitting there, talking about various things. That's something I didn't get to do because I was eight when he passed. But what I really miss is my family singing. That was a fabulous thing. If we were together working, doing something, one of us might start a song and the others would chime in, and we sang together so much, we were so rehearsed, we knew all the harmonies—and were immediately singing in four-, five-, or six-part harmony—and it was just huge fun.