II

WHO’S WHO IN THE TWELVE CAESARS

‘It’s Caesar!’

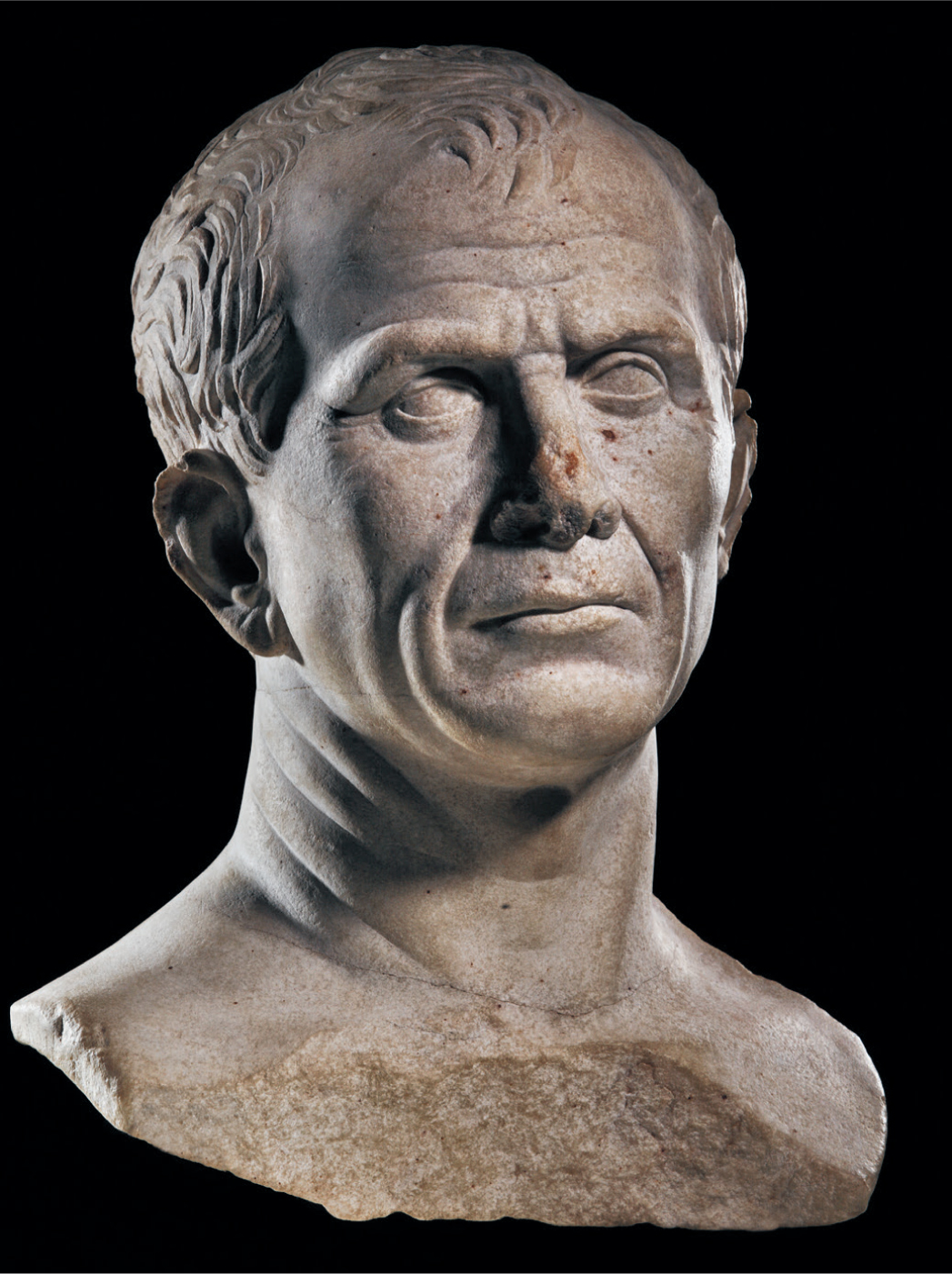

In October 2007, French archaeologists exploring the bed of the river Rhône at Arles dragged a marble head out of the water (Fig. 2.1). It was apparently still dripping when the director of the team shouted, ‘Putain, mais c’est César’ (‘Fuck, it’s Caesar’ probably captures his surprise better than any other, more polite, translation). Since then, this head has been the subject of dozens of newspaper articles and at least two television documentaries, it has been the star of an exhibition shown in Arles and at the Louvre, and in 2014 it even appeared on French postage stamps.1

Part of this attention has been sparked by one very special claim, that the head is not simply a portrait of Julius Caesar, but is one of the holy grails in the study of Roman portraiture: an image of Caesar sculpted in his lifetime by an artist who had studied him face to face. If so, it would be the only certain example to survive (though other candidates have over the years been proposed). The assumption is that the bust was originally set up in some prominent place in the Roman city of Arles, redeveloped by Caesar in 46 BCE as a settlement for his veteran soldiers; and that, after Caesar’s assassination in 44, fearing that their Caesarian connections might prove (to say the least) awkward, the locals decided to dispose of this potentially hot property in the river, where it lay for over two thousand years.

Modern archaeologists and art historians are still divided on the identity and significance of the find. Sceptics emphasise how different overall the head from the Rhône appears to be from Caesar’s portrait on contemporary coins—and different too from other, admittedly posthumous, portraits commonly identified as him. The supporters of the identification, by contrast, stress the specific points of similarity between this head and some individual features on the coin portraits, notably the lines in the neck and the prominent Adam’s apple (Fig. 2.3). A few come close to claiming that the fact that it does not in general look much like the other Caesars could actually be confirmation that it is an authentic and unique image carved from life, and not a run-of-the-mill replica piece—an ingenious ‘have it both ways’ style of argument (it’s Caesar whether it looks like him or not) that doesn’t inspire confidence.2

2.1 The ‘Arles Caesar’, a portrait bust dragged out of the river Rhône to a huge fanfare in 2007. Whether it is really an image of Julius Caesar himself is a matter of debate, but its supporters point to the prominent lines on the neck, one of Caesar’s characteristic features.

2.2 The Great [i.e., ‘big’] Cameo of France, roughly thirty by twenty-five centimetres, captures one view of Roman hierarchy: the emperor Augustus, at the top, looks down from his afterlife in heaven; in the centre, the emperor Tiberius holds court, next to his mother Livia; at the bottom huddle the conquered barbarians. Made around 50 CE, and on display in France since the Middle Ages (hence its title), it is certainly not a biblical scene as once thought. But who exactly all the minor members of the imperial family are remains a puzzle.

2.3 This coin (a silver denarius) minted in 44 BCE shortly before Caesar’s assassination has often been taken as the key to his appearance, with a prominent Adam’s apple, wrinkly neck and a wreath possibly carefully placed to cover up a bald patch. Caesar’s name and title run around the coin edge: ‘Caesar Dict[ator] Quart[o]’ (dictator for the fourth time). Behind his head is a symbol of one of his priesthoods.

Despite the scepticism (and I am one of the sceptics), it seems as if this is set to be the face of Julius Caesar for the twenty-first century—taking its place as the most recent in a series of favoured portraits of him that have held sway for a time in the popular and scholarly imagination, before being pushed aside by a rival contender. But, whatever the credentials of the piece, it opens up some big questions that will guide this chapter. What was the purpose, and the politics, of portraiture in the Roman world itself? How did its role change through the reign of Caesar and his successors? How (and how reliably) have ancient portraits of these rulers been identified, when almost none are named or carry any other identifying mark? Before we can start exploring modern re-creations of these imperial rulers, we need to consider how the original Roman versions of them have been pinned down, from the Caesar of the Rhône through the godlike serene images of the emperor Augustus to some strange outliers—such as the famous Grimani head of ‘Vitellius’ (Fig. 1.24) which, as we shall discover at the end of this chapter, was not only a favourite model for modern artists but has had a starring role in scientific debates, from the sixteenth century on, about the relationship of the shape of the skull to human character.

It turns out that we are not necessarily any better now at identifying emperors in ancient portraits than our predecessors were hundreds of years ago. True, a few very old errors, often going back to the Middle Ages, have been overturned, some spurious emperors have been dethroned, and those masquerading under entirely different identities have been conclusively revealed as rulers of the Roman world. The idea that the famous bronze statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius on horseback on the Capitoline hill in Rome actually represented a humble local strongman who had saved the city from an invading king has long been written off as a piece of garbled medieval folklore, or more generously as an ingenious reappropriation of the ancient past (Fig. 1.11).3 And the traditional notion that one particularly splendid ancient Roman cameo depicted the biblical scene of the triumph of Joseph at the court of the pharaoh was demolished by a learned friend of Peter Paul Rubens, who around 1620 correctly pointed out that it was instead a family group of the emperor Tiberius, complete with Augustus looking down from heaven and some benighted barbarians underneath (Fig. 2.2). The old reading was a tremendous tribute to the Christian talent for finding a religious message in the most unlikely places, and it may well help to explain why the cameo was preserved. It was also flagrantly wrong.4

But such cases are rare. Historians in the twenty-first century are still spotting emperors by much the same methods as those in the fifteenth or sixteenth, we are still debating the pros and cons of many of the same objects and we can on occasion be more gullible than the shrewd scholars of the past. In the eighteenth century, J. J. Winckelmann reported that Cardinal Albani, famous collector and connoisseur, was doubtful that any genuine heads of Julius Caesar had survived. Whatever exactly he meant by ‘genuine’, I suspect that Albani would have had his doubts about the specimen from the Rhône.5

Julius Caesar and His Statues

In Roman history, Julius Caesar stood on the boundary between the free Republic (that power-sharing regime so beloved of anti-monarchists from the Founding Fathers to the French revolutionaries) and the autocratic rule of the emperors. He marked the end of one political system and the beginning of another. Although its rights and wrongs have been debated ever since, his story in outline was simple. After a fairly conventional early career, winning election to a regular series of political, military and priestly offices, by the middle of the first century BCE, Caesar stood out above most of his political peers. He had been a massively successful conqueror even by Roman standards (so brutal that some of his own countrymen occasionally muttered about war crimes). And he had won enormous support from the ordinary people of Rome, thanks largely to a number of high-profile popular measures, such as land distribution and free grain rations, which he had either initiated or supported. By 49 BCE, he was unwilling any longer to toe the line within conventional politics, and in a civil war against the traditionalists (or ‘the uncompromising reactionaries’, depending on your point of view), he fought his way to what was in effect one-man rule. Within a few years he was made ‘dictator for life’, turning an old Roman emergency-powers office of dictator into dictatorship in the modern sense. His assassination was carried out under the slogan of ‘Liberty’, the watchword of the old republican regime. But if his assassins really wanted to undo the autocratic turn at Rome, they failed. Within less than fifteen years, after another civil war, Caesar’s great nephew Octavian (later to take the name ‘Augustus’) had established himself on the throne, and devised a form of autocracy that would last for the rest of Roman time.6

By starting his series of imperial biographies with Julius Caesar, Suetonius turned him into the first emperor of Rome. Few historians in recent years have followed this line. Although Caesar inevitably faces two ways, we now tend to see him more as the last chapter of the Republic, as the death blow to a political system that had been tottering for decades, unable to accommodate the ambition, wealth and power of a new generation of leaders (Caesar was not the only one moving in this direction). Being dictator was a long way from being emperor (or from being princeps, which is the closest Latin equivalent of that term). But Suetonius’s alternative view does alert us to the ways in which Caesar left his stamp on the system of one-man rule that was to follow him.7 Most obviously, he gave his personal name to all his successors. Every Roman emperor ever after took ‘Caesar’—which up to then had been no more than what we would call an ordinary surname—as part of his official title. And that remained the case right down to the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire into the nineteenth century (whether as ‘Caesar’ or ‘Kaiser’) or to other look-alikes, such as the ‘Czars’. When we talk about the Twelve Caesars, that is exactly what they were.

Julius Caesar also established a template for the future with an entirely new use of images. He was the first Roman to have his portrait systematically displayed on coinage. A few precedents for this had been set by the kings and queens who came after Alexander the Great in the Greek world, but in Rome itself only the imaginary portraits of long-dead heroes had ever featured on coin designs. It was Caesar who firmly set the tradition, lasting in many places until the present day, that the head of the living ruler belonged in the purses of his subjects.8 He was also the first to use multiple statues of himself to parade his image to the public in Rome and much further afield.

A tradition of portraiture at Rome went back long before Caesar, of course. It is now often seen as a distinctively Roman genre of art, embedded in the rituals and practices of Rome’s aristocracy and of Roman public life: images of ancestors were displayed at the funerals of the elite and were part of the furniture of their houses; statues of prominent individuals, bigwigs and benefactors, had for centuries stood in the public squares, temples and market places of the Roman world.9 In fact, in the Western tradition at least, the now common convention of allowing a marble head to stand for the whole body—‘a head the sculptor severs in one’s lifetime’ as Joseph Brodsky put it in his eerie poem on a bust of the emperor Tiberius—appears to have been a Roman innovation. In classical Greece, portraits had usually been full-length figures, and there were plenty of those in Rome too. But it was the Romans who made it seem (almost) natural that an image truncated at the neck or shoulders could stand for a person rather than a murder victim. In that sense, and others, our idea of the ‘portrait head’ goes back to Rome.10

Caesar was the first to go beyond this and to engineer the widespread replication of his image, hundreds of times over. Never before had portraits been used so concertedly to promote the visibility, omnipresence and power of a single person—in quantity and in strategic placing. One Roman historian, admittedly writing two hundred years later, reports a decree issued during his lifetime that there should be a statue of Caesar erected in every temple at Rome, and in every city of the Roman world; and Suetonius mentions that on particular occasions his image was carried in procession alongside those of the gods. Caesar’s head being placed on the shoulders of the statue of Alexander was only one loaded use of portraits among many.11

How, or by whom, all these images were produced is a mystery. I very much doubt that Caesar patiently posed for battalions of sculptors; maybe none of the portraits were done from life in the strictest sense of the term. And some of the claims about their vast numbers may well have been wishful thinking or scaremongering, or else reflected plans never carried out in the short time that he held power. Nonetheless it seems certain that portraits that were intended to be, and were generally taken as, ‘Julius Caesar’ spread across the Roman landscape as those of no single individual had ever done before. At least eighteen pedestals have been discovered in what is now Greece and Turkey, with inscriptions to show that they originally held a statue of Caesar put up while he was still alive; three more are known in the towns of Italy, and Arles and the other towns of Gaul may well have had their fair share too.12 And that tradition continued for centuries after his death. Across the Roman Empire, there were any number of attempts (sometimes much later) to commemorate in ‘portraits’ the man who gave his name to the long succession of Roman rulers. Perhaps those images of Caesar as conquering hero and proud ancestor of the imperial regime did something to assuage the grim precedent of his assassination that must have haunted many of the rulers who came after him.

There is no reason at all why some of these statues should not have survived to the present day—whether those sculpted during his lifetime (the ‘holy grails’), or the even more numerous later copies of them, or variations on the theme, that were created after his death. The tricky question is how we can recognise any such survival when we find it, and what would convince us that it was intended as a portrait of Caesar rather than of anyone else. Everything hangs on that.

Many of the obvious diagnostic clues that we might expect are now missing, or never existed. There are, to start with, no helpful labels. Not a single statue has ever been discovered still attached, or even adjacent, to a pedestal carrying his name (and if a bust has ‘Julius Caesar’ inscribed on its base, that is a strong indication that the bust—or the inscription—is modern). Nor do images of Roman rulers, unlike those of Christian saints, ever become associated with symbols that point to their identity. There was nothing like the keys of Saint Peter or the wheel of Saint Catherine for the Caesars. And their bodies never gave any hint of who they were. Whether the emperor concerned was thin or fat, tall or short, there was no reference to that in their full-length statues, which are more or less identical figures, clad in a toga, armour or heroic nudity. There are no portly Henry VIIIs, or hunched Richard IIIs. With Roman rulers everything comes down to the face.

From the moment antiquarians and artists half a millennium ago first started systematically to identify Roman portraits, to the moment the marble head was dragged out of the Rhône, all attempts in the modern world to pin down the face of Caesar have overwhelmingly relied on two key pieces of evidence. The first is Suetonius’s colourful and intimate description of the dictator’s appearance, complete with his ruses for disguising his baldness and his enthusiasm for depilation:

He is said to have been tall in stature, fair-skinned, with slender limbs, a rather full face, and sharp dark eyes.… He was particularly fastidious over his body image, so that not only was he carefully trimmed and shaved, but also, according to some critics, he used to pluck his body hair, while seeing his baldness as a terrible disfigurement, since he found it exposed him to the jibes of abusers. So, he used to comb forward his thinning hair from the crown of his head, and out of all the honours decreed to him by the senate and people, there was no other that he received and made use of more gladly than the right to wear a laurel wreath at all times.13

The second is the series of silver coins issued in early 44 BCE, showing him with that lined neck, Adam’s apple, a strategically placed wreath and his name spelled out around the edge (Fig. 2.3). The truth is that there are other coins with heads—not of Caesar at all, but of characters from Roman myth and history—that show similar distinguishing marks on neck and throat, not to mention coins depicting Caesar on which he looks decidedly different.14 But leaving such variants aside (as they are usually left, without an inconvenient second look), this memorable image has always claimed more authority than any other evidence as the baseline for identifying the bona fide face of Caesar.

To be fair, material of this kind puts us in a better position to identify Caesar and his successors than any other Roman characters ever; the faces of Cicero or the Scipios, or Virgil or Horace, are irretrievably lost to us in a way that the faces of the emperors are not entirely so; no Roman poets ended up on the coinage as British authors may, occasionally and controversially, end up on banknotes.15 Even so, there is no sophisticated modern technique that can precisely pinpoint an image of Caesar. If you want to claim a particular sculpted head as his portrait, all you can do is what has always been done: that is, try to match the candidate up to the canonical coin portraits and to the physical details highlighted by Suetonius. It is a subjective process of ‘compare and contrast’, relying as much on the rhetoric of persuasion (can you convince yourself, as much as anyone else, that you are right?) as on objective criteria. And it is much more difficult than any quick summary makes it seem.

Even supposing that Suetonius, who was writing a century and a half after Caesar’s death, actually knew what his subject had looked like, it is next to impossible to align any surviving image with Suetonius’s description. That is partly because the details he highlights—the colour, the texture, even the thinning hair—do not convert easily into marble. (It may be reassuring to know that men have been ‘combing over’ to conceal their baldness for two thousand years, but how exactly would you expect a sculptor to represent the trick?) But it is also because Suetonius’s Latin is in places ambiguous. The phrase that I have translated as ‘a rather full face’ (ore paulo pleniore) could equally well mean ‘a disproportionately large mouth’, which would send us on the hunt for a very different set of features.16 In any case, neither translation comfortably fits the portraits on the coins, where Caesar seems if anything rather gaunt, and has a perfectly ordinary sized mouth. And those coins present their own problems. As antiquarians already saw more than two hundred years ago, the process of comparison between a tiny two-dimensional head, not much more than a centimetre tall, and a life-size portrait in the round, is extremely tricky. Winckelmann (just before reporting Cardinal Albani’s general scepticism on portraits of Caesar) admitted that he could not find any sculptures that he thought were a close enough match for the coins. But at least one fellow connoisseur at the time went further: he more or less implied that it was not simply a question of finding a satisfying resemblance, but more fundamentally of deciding what exactly would count as a resemblance between these two very different media.17

So how does this work out in practice? Intriguing as these dilemmas about method are, they hardly prepare us for the ferocity of the debates over rival sculptures of ‘Caesar’, for the hyperbole of the claims made in their favour or for the impact of the discussion far beyond the world of professional archaeologists, artists and collectors. (Benito Mussolini is only one infamous ‘celebrity’ with a stake in these controversies, and there are unexpected Bonapartist connections too.) The story of two pieces, in particular, that were in turn the favourite candidates for the authentic face of Caesar from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, illustrate the surprising twists and turns of scholarly fashion and the sometimes learned, sometimes implausible arguments mounted on different sides. They help us to think harder about how modern viewers over the centuries have learned to see Caesar.

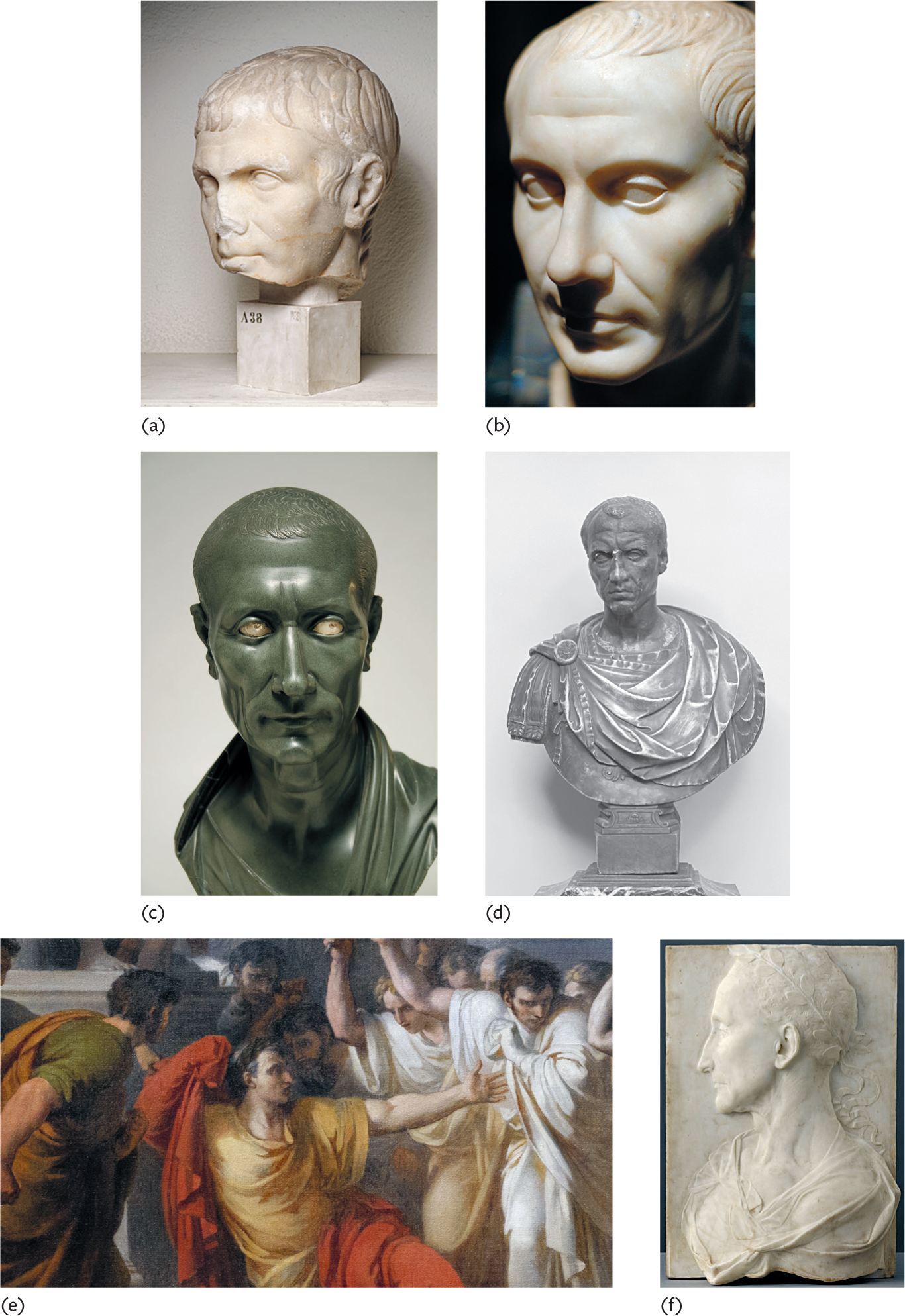

Pros and Cons

Apart from the coins, more than a hundred and fifty portraits have at one time or other been seriously claimed to be ancient Roman images of Julius Caesar (the number varying according to how stringently you take the word ‘seriously’). They are mostly in marble, but there are some candidates on gems too, and in ceramic.18 They are now found in collections across the Western world, from Sparta, Greece to Berkeley, California, and a few have emerged from improbable places. The head from the Rhône is not the only one to have been discovered in a river. Another specimen, whose current home is a museum outside Stockholm, was mysteriously dredged up in 1925 from three metres of mud in the bed of the Hudson, by 23rd Street in New York: it must somehow have been ‘lost’ overboard from a boat carrying a cargo from Europe (my inverted commas convey my puzzlement about the circumstances), rather than be stunning proof of all those claims that the Romans really had reached America (Fig. 2.4a).19 Out of this number, there are hardly any whose identification or authenticity has never been questioned. One such is a marble head found along with other recognisably imperial portraits in 2003 in excavations on the island of Pantelleria, between Sicily and North Africa, in what seems to have been a later dynastic group, including a retrospective ‘portrait’ of Caesar as its founding father (hence the greater than usual certainty about who it is); but in time this too may well find its challengers (Fig. 2.4b).20 Almost every single other piece has been periodically under fire: either on the grounds that, while it may be ancient, it is certainly not Caesar, or because, while there is little doubt that it is intended to be Caesar, it is certainly not ancient, but a modern replica, version or fake.21

The conflicting claims can be baffling in their variety. The head from the Hudson, for example, has also been thought to be Augustus or his right-hand man Agrippa, alternatively Sulla (the notoriously murderous despot of the early first century BCE) or now more often just another ‘unknown Roman’. Particularly hard to pin down has been the ‘Green Caesar’, once a prized possession of Frederick II of Prussia, now in Berlin, and named for the distinctive Egyptian green stone from which it is made. Where it was found is entirely unknown, but its Egyptian connections have proved hard to resist. Is it, as one writer has recently hoped on almost no evidence at all, the very statue that Cleopatra put up in honour of Caesar in Alexandria after his death? Is it perhaps no more than a portrait of ‘one of Caesar’s admirers from the Nile’, aping the style of his hero? Or is it actually an eighteenth-century fake, but intended to pass for Caesar all along? Who knows?22 (Fig. 2.4c)

Among all these Caesars, some have earned more fame than others, and at different periods. One early favourite was the ‘true portrait’ housed in the sixteenth century in the palazzo of the Casale family in Rome. According to a remarkable contemporary guidebook, written when its author, Ulisse Aldrovandi from Bologna, was detained in Rome under the Inquisition, this bust’s owner kept it under lock and key, but would show it to visitors ‘lovingly’. (If it is the same bust of Caesar still in the collection of the Casale descendants, it is now often reckoned that this prized possession was no antique at all, but only a century or so old at the time.)23 (Fig. 2.4d)

In the 1930s, Mussolini brought to prominence a full-length Caesar that used to stand in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline hill in Rome. This had once been much admired by travellers to the city and was one of only two Caesars accepted as incontrovertibly ‘Caesarian’ by another of those hard-headed critics in the late eighteenth century. It later fell from favour under the usual whiff of suspicion that it might be a modern, seventeenth-century pastiche: in this case, needlessly (true, there has been a lot of ‘work’ done to the arms and legs, but a sketch of it dated to 1550 knocks on the head the idea that it was a seventeenth-century creation). In any case, no such doubts prevented Mussolini from making it his own trademark image of Caesar, and the symbol of his ambitions to follow in the footsteps of the Roman dictator.24 ‘Il Duce’, as Mussolini was known, had the sculpture moved from its home in the Conservatori courtyard to give it pride of place in the Roman city council chamber in the next-door Palazzo Senatorio, where it still presides over discussions of planning regulations and parking fines. In a programme uncannily reminiscent of the replication of Caesar’s statues two thousand years earlier, he also had copies of it made to stand both in Rimini in northern Italy, from where Caesar had launched his final bid for power in Rome, and next to his brand new highway in the centre of Rome (via dell’Impero, or ‘Empire Street’, as it was then known; later renamed, after the adjacent archaeological remains, via dei Fori Imperiali, or ‘Street of the Imperial Fora’) (Fig. 2.5).25

2.4

(a) The ‘Caesar’ from the Hudson River

(b) Julius Caesar (mid-first century CE) from Pantelleria

(c) The Green Caesar, assumed to originate in Egypt

(d) The Julius Caesar now in the Casali Collection in Rome

(e) Head of Caesar from Vicenzo Camuccini, Death of Caesar (1806)

(f) Head often identified as Caesar, by Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1460)

2.5 Benito Mussolini announces the abolition of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, in March 1936. Appropriately enough he spoke directly in front of the statue of Julius Caesar, which he had ordered to be moved to this council chamber: one dictator in front of another.

But the clearest insight into what the modern world has been searching for (and sometimes inventing) in images of Caesar, and into the strange narratives that can lie behind mute sculptures on museum shelves, comes in two marble heads that one after the other became the defining images of Caesar: one in the British Museum in London, the other in the Archaeological Museum in Turin. Almost any surviving sculpture of ‘Caesar’ has some similar, if lower-key, story attached (a succession of authentication, de-authentication, admiration and disdain); but this pair illustrate better than any others some of the most vivid disputes that ‘Caesars’ can provoke.

The first was bought by the British Museum in 1818, among a group of objects acquired from James Millingen, a British collector and dealer in Italian antiquities (Fig. 2.6).26 Where, or how, it was discovered is not recorded, and it was not at first treated as anything special, being assumed cautiously to be an ‘unknown head’. But about 1846, according to the Museum’s hand-written catalogue, it was re-identified as a portrait of Julius Caesar.27 Who did this, and on what grounds, is a mystery (presumably the similarity to coin portraits came into the argument somewhere). But for decades this image held sway as the Caesar of modernity’s dreams. It illustrated biographies of the dictator, it appeared on any number of book jackets and it prompted what in hindsight seems embarrassingly extravagant prose.

In 1892, a particularly gushing encomium came from Sabine Baring-Gould, best-selling British author, Anglican clergyman and a man remembered more now as a hymn writer (‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ was his most famous anthem) than as a Roman historian. He conceded that the artist might have overlooked Caesar’s baldness, and that he probably did not sculpt the portrait from life (a disappointment that lurks in the background of many of these discussions). But it was certainly ‘done by a man who knew Julius Caesar well, who had seen him over and over again, and had been so deeply impressed by his personality that he has given us a better portrait of the man than if he had done it from life.… he caught and reproduced those peculiarities of his expression which Caesar’s face had when in repose, the sweet, sad, patient smile, the reserve of power in the lips, and that far-off look into the heavens, as of one searching the unseen, and trusting in the Providence that reigned there.’28 Soon after, Thomas Rice Holmes, another passionate Caesarian, followed a similar line at the start of his history of Caesar’s conquest of Gaul: ‘The bust represents, I venture to say, the strongest personality that has ever lived.… In the profile it is impossible to detect a flaw.… He has lived every day of his life, and he is beginning to weary of the strain, but every faculty retains its fullest vigour.… The man looks perfectly unscrupulous; or … he looks as if no scruple could make him falter in pursuit of his aim.’29 John Buchan too, classicist, diplomat and author of The Thirty-Nine Steps, writing in the 1930s called it ‘the noblest presentment of the human countenance known to me’ even if he struck a different chord from the others in admiring ‘the fine, almost feminine, moulding of the lips and chin’. ‘Caesar’, he insisted, ‘is the only great man of action, save Nelson, who has in his face something of a woman’s delicacy.’30

2.6 Acquired by the British Museum in 1818 as an ‘unknown Roman’, from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century, this life-size bust was the most famous, and most reproduced image of Caesar. It is now generally thought to be an eighteenth-century fake or pastiche.

It is now hard to take this kind of prose seriously. The special pleading (‘it wasn’t done from life, but it is even better than if it were’) grates, and the hyperbole seems out of all proportion to the portrait itself, especially for those of us who are not so convinced of Caesar’s unmitigated ‘greatness’. But it is, nevertheless, clear what lies behind it. The priority of these writers was to claim a face-to-face encounter with the human being captured in the marble—even if, in practice, they were doing little more than finding an appropriate image onto which they could project their various assumptions about ‘Caesar the man’, from visionary power through a hint of unscrupulousness to an uncannily female side. There is also a hint, as Rice Holmes almost admits, that the passion is partly compensating for the lack of a really hard argument behind the identification of this head with Caesar. And that indeed was to become the problem. For what if the British Museum’s bust was not really Caesar? Or was not even ancient Roman?

Doubts began to show very soon after 1846, when the statue was given the name of Caesar. A museum handbook published in 1861 took care to rebut a claim that this was not Caesar at all, but one of his contemporaries: ‘There have not been wanting critics who have strenuously maintained that it is really a pourtrait <sic> of Cicero. We cannot, however, acquiesce in this view’.31 But worse was to come. In 1899, the German art historian Adolf Furtwängler pronounced the head not ancient at all (‘a modern work with fabricated corrosion’) and, even though this had hardly been more than a passing swipe, the doubts had forever after to be acknowledged even by those who were keenest to dismiss them (along the lines of ‘The antiquity of the British Museum head has been called into question, but …’).32 By the mid 1930s, at roughly the same time as Buchan was penning his encomium, this ‘noblest presentment of the human countenance’ was being moved from pride of place in the Roman galleries to a still prominent, but less chronologically specific location, at the entrance to the Museum’s library. Its label left no room for doubt: ‘Julius Caesar. Ideal portrait of the eighteenth century. Rome, bought 1818.’ One regular visitor regretted this demotion, ruefully calling to mind Caesar’s famous quip on divorcing his second wife in 62 BCE, while pointing also to the gullibility of those who bought fakes in Italy. There was a terrible warning in this famous head: ‘he, who insisted that his wife must be above suspicion, now only serves to warn the unsuspicious Englishman against buying sham antiques abroad’.33

This Caesar has never been reinstated as a genuine ancient piece, and it has since passed from the care and control of the Museum’s Greek and Roman Department to the British and Medieval Department and back again, as if no one could quite decide where the awkwardly illegitimate specimen belonged (one thing is for certain: it is neither British nor medieval). It was only in 1961, however, that a detailed technical case was made against it: by Bernard Ashmole, who had been the Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum between 1939 and 1956. Ashmole emphasised the suspiciously brown colour of the whole piece. Had tobacco juice been applied to it, he wondered, as part of the forger’s armoury for producing an ‘antique’ patina? But the real give-away was the pitted texture of the skin. Its supporters had put this down to the (ancient) head having been cleaned with acid (which was certainly part of the eighteenth-century repertoire of ‘treatments’), though Furtwängler had already suggested it was ‘fabricated corrosion’. Ashmole argued more precisely that the cause was physical battering—‘distressing’ is the technical term—carried out with the fraudulent intention to make it appear old. Indeed, he pointed out, you could see patches of smooth marble remaining, where the distressing had stopped a little short of the hairline. This appeared to be the conclusive proof. The sculpture is no longer on show at all, though it does occasionally emerge from its basement exile to star in exhibitions of notorious fakes.34

At almost exactly the same moment, however, there was another portrait waiting in the wings to take this Caesar’s place. In the early years of the nineteenth century, Lucien Bonaparte—archaeologist, collector, sometime revolutionary and younger (partly estranged) brother of Napoleon—discovered a marble head in excavations near his house just south of Rome, on the site of the ancient town of Tusculum. It did not particularly stand out among the finds and, like the British Museum head, it was identified at first not as a Caesar but as a generic ‘old man’ or ‘old philosopher’. After Bonaparte hit hard times both politically and economically, it ended up in the hands of new owners in a castle at Aglié outside Turin, where it remained anonymously for a hundred years or so.35 It was only in 1940 (an auspicious moment for discovering Caesars in Italy, given Mussolini’s enthusiasm) that an Italian archaeologist, Maurizio Borda, argued that it was in fact Julius Caesar (Fig. 2.7).

This was on the usual grounds of the similarities to the coin portraits of 44 BCE, but Borda went further. Not only did he conclude that the similarities were so close that the portrait must have been made during Caesar’s lifetime, but he also felt able to use the sculpture to diagnose two deformations of the skull from which Caesar had obviously suffered. The slightly odd shape of the head was not caused by incompetence, or idiosyncrasy, on the part of the artist. It was an accurate reflection of two congenital cranial pathologies, clinocefalia (a slight depression at the top of the head) and plagiocefalia (a flattening on one side of the skull). This portrait has rivalled the British Museum Caesar in the hyperbole it has prompted. ‘The almost imperceptible movement of the slightly lifted head, and the momentary contraction of the forehead and the mouth, tell of a watchful and superior presence,’ wrote one art historian only recently, praising its ‘psychological realism’. ‘In the look of the eyes, slightly converging, one has the impression of discerning a certain aristocratic reserve or irony.’36 But, even more than its British Museum rival, the Tusculum head has been considered to be so close to life that it could support a clinical diagnosis: this is not just looking Caesar in the eye, it is taking his case notes.

2.7 The favourite Julius Caesar of the mid-twentieth century. Excavated in the early nineteenth century at the site of Tusculum in Italy, it was at first identified as an anonymous ‘old man’, but re-identified in 1940 as the authentic, life-size, face of Caesar. Beyond the lines on the neck, here the shape of the skull has been taken to indicate a cranial deformity (from which Caesar may, or may not, have suffered).

Here too views have begun to change. The Caesar from Tusculum still has its enthusiasts, and in 2018 it was used—with much international media attention—to produce a full-scale, ‘scientific’ reconstruction of the authentic face of the dictator.37 But even among its supporters, many no longer insist that it is a portrait taken from life (let alone the only such to have survived); still less that it is another of those holy grails of Roman portrait studies, an image made from the man’s death mask.38 They concede that it is much more likely a copy or version of an earlier sculpture in bronze that has been lost, and they group it together with four other ancient, though later, ‘Caesars’ (including the recent discovery at Pantelleria), in which there are arguably traces of similar oddities of the skull—as if they were all based on that same bronze original.39 Far from the high-flown praise for its artistic quality with which Borda had greeted the head, there are also those who now rate it as a rather rough, or at least very badly corroded, piece of work (‘a mediocre copy’). It may well be only a matter of time before it is relegated back to the status of ‘unknown old man’. Its return to anonymity will certainly be eased, or hastened, by the fact that the Caesar from the Rhône is already there to take its place, and being greeted with all the same acclamations. Museum visitors confronting it for the first time (and using social media as eighteenth-century travellers used their journals) have reported themselves ‘transfixed by the sheer presence emanating from it’, unable to tear themselves away from the sight of the great man. This is not so very far from John Buchan and friends.40

2.8 Behind the ear of the British Museum Caesar, evidence of unfinished work—in a series of drill holes, made in the process of separating the ear from the head, but never intended to remain in the final, finished piece.

But these certainties are always shifting and more surprises lie in store. There is even an outside chance that the British Museum Caesar may one day be rehabilitated as authentically ancient (even if not necessarily a Caesar, or not necessarily taken from life). For, almost unnoticed, behind both ears, on one side more clearly than the other, runs a line of drill holes (Fig. 2.8). These are signs of unfinished work. Following a pattern found on genuinely ancient sculptures, the sculptor has started the delicate business of freeing the ear from the head (delicate, because it is very easy to break the ear off as you do it). He has speeded up the process by drilling these holes, but he has not done the final work with the chisel to make a clean gap. How is that to be explained? Possibly this is an unfinished fake (late eighteenth-century sculptors could well have been using the same techniques as their ancient forebears and it is not only genuine articles that might be left incomplete). Possibly it is a double bluff by some modern craftsman, hoping to add an aura of authenticity to the work, through that sense of a slight flaw. But those who sell fakes do not usually trade in imperfection. Whatever the other signs of modernity, those little holes may eventually re-open the question of exactly where on the spectrum between ancient and modern this sculpture lies. Whether it will ever re-emerge from its basement exile, who knows?41

The ‘Look’ of Caesar

The story of the ancient face of Caesar can seem a frustrating series of about-turns, dead ends, identifications and re-identifications. For decades one particular portrait is treated as the most accurate and authentic image of the dictator; then, for reasons that are not obviously stronger than those that gave it the fame in the first place, it is sidelined as a fake, as not Caesar anyway or simply as a later second-rate hack copy of some original masterpiece, now lost to us entirely. It is as if, over the last couple of hundred years (and the pattern surely goes back earlier), every generation or so has homed in on its favourite Caesar, which holds sway for a while, offering the modern world that precious opportunity to look Caesar directly in the eye and to see through the marble image to the personality—even the clinical pathology—of the man behind it. In due course this is toppled by some new discovery, or rediscovery, and fades back into relative obscurity; while other members of the supporting cast, such as the ‘Green Caesar’ or Mussolini’s version, slip in and out of the limelight. For those relegated, the distinction they retain (rather like Jesse Elliott’s misidentified sarcophagi) is that they were once thought to be Caesar.

Yet despite these seemingly endless debates and disagreements, Julius Caesar is one of the most easily recognisable of all Roman rulers in the art of the modern world, in painting, sculpture and ceramics, cartoons and films, as well as in fakes and forgeries. Among any collection of Renaissance busts of the Twelve Caesars, he usually stands out as the slightly gaunt one with the aquiline features, though not necessarily the scraggy neck and Adam’s apple. That is how he is depicted too in almost every painting or drawing, from Mantegna’s slightly sinister figure in his triumphal chariot (Fig. 6.7), through Camuccini’s dying dictator (Fig. 2.4e) to the cartoon version of Astérix, complete with wreath and disconcertingly staring eyes (Fig. 1.18i). And it is exactly those features that have always made it tempting to imagine that Desiderio’s delicate marble sculpture, one of the high points of fifteenth-century craftsmanship, was intended as an image of Caesar, despite—as in all its ancient predecessors—the complete absence of a name (Fig. 2.4f).42 The ‘look’ of Caesar (and I choose my words carefully) is easy to spot.

That ‘look’ is, of course, a complicated, multi-layered and self-reinforcing stereotype, and one of the best examples of those entanglements between ancient and modern that I discussed in Chapter 1. Part of it certainly derives from the memorable heads on the coins of 44 BCE, part from full-sized sculptures believed to be ancient representations of Caesar (some of which were almost certainly not) and part from the words of Suetonius. But artists have also responded to the work of their modern peers and predecessors, who in the process of re-creating the image of Caesar—in painting, sculpture or even on the stage—helped to establish a touchstone by which his future representations would be judged.43

It is impossible to know how far this composite resembles the dictator’s appearance in flesh and blood. Most people would, I think, claim some overlap between them; but however large or small the overlap was, that set of features successfully signals ‘Caesar’ to us. My guess is that they would roughly have signalled ‘Caesar’ to Roman viewers too; it would not have been difficult for many of them to work out who was standing in Mantegna’s triumphal chariot, or ticking off the troublesome Gauls in the comic strip.

The Forward Plan

The portraits of none of Julius Caesar’s successors have attracted quite such lavish encomia and gushing hyperbole, or been so fiercely debated. But Augustus, Caligula, Nero and Vespasian have all recently starred in their own exhibitions, and over the last couple of hundred years there have been other ‘mais c’est César’ moments as images of later emperors came spectacularly to light; or so it was claimed. One of the most recent, and most unconvincing, examples is a headless, and partly body-less, seated marble figure, seized from ‘tomb raiders’ by the Italian police in 2011, and almost instantly hyped as the emperor Caligula—with plenty of juicy allusions to his madness, debauchery and promiscuity thrown in.44 Without a face to go on, unless a battered, more or less featureless, head discovered not far away actually belonged to the piece, the identification relied heavily on the statue’s elaborate sandal, which was taken to be one of the military boots or caligae the emperor wore as a toddler and was the source of the nickname ‘Caligula’ by which he is now usually known. Few people chose to ask why on earth, in this once rather grand sculpture, there should have been a visual reference to the childish nickname (‘Bootikins’ gets the flavour) that the emperor, officially known as ‘Gaius’, is said to have loathed. Such is our desire to rediscover the famous, and infamous, emperors.

By and large these later rulers have been tracked down by the methods very like those used in the hunt for Caesar. The same subjective procedure of compare and contrast—with Suetonius’s description or the tiny coin portraits—underlies most identifications and has long been so taken for granted that in the eighteenth century one trick of the ciceroni, or tour guides, was to carry round a pocketful of ancient coins to help their clients give a name to the statues they were looking at.45 There are similar arguments with Caesar’s successors too about how to distinguish an emperor made by a modern sculptor from one produced in the Roman world itself; and there are any number of hopeless examples of wishful thinking, changing identities and deeply disputed cases. A pair of statues found in a building off the Forum in Pompeii has kept archaeologists busy for decades, trying to decide (on no firm evidence at all) whether they are some lofty imperial couple or two ambitious local dignitaries aping the imperial style.46

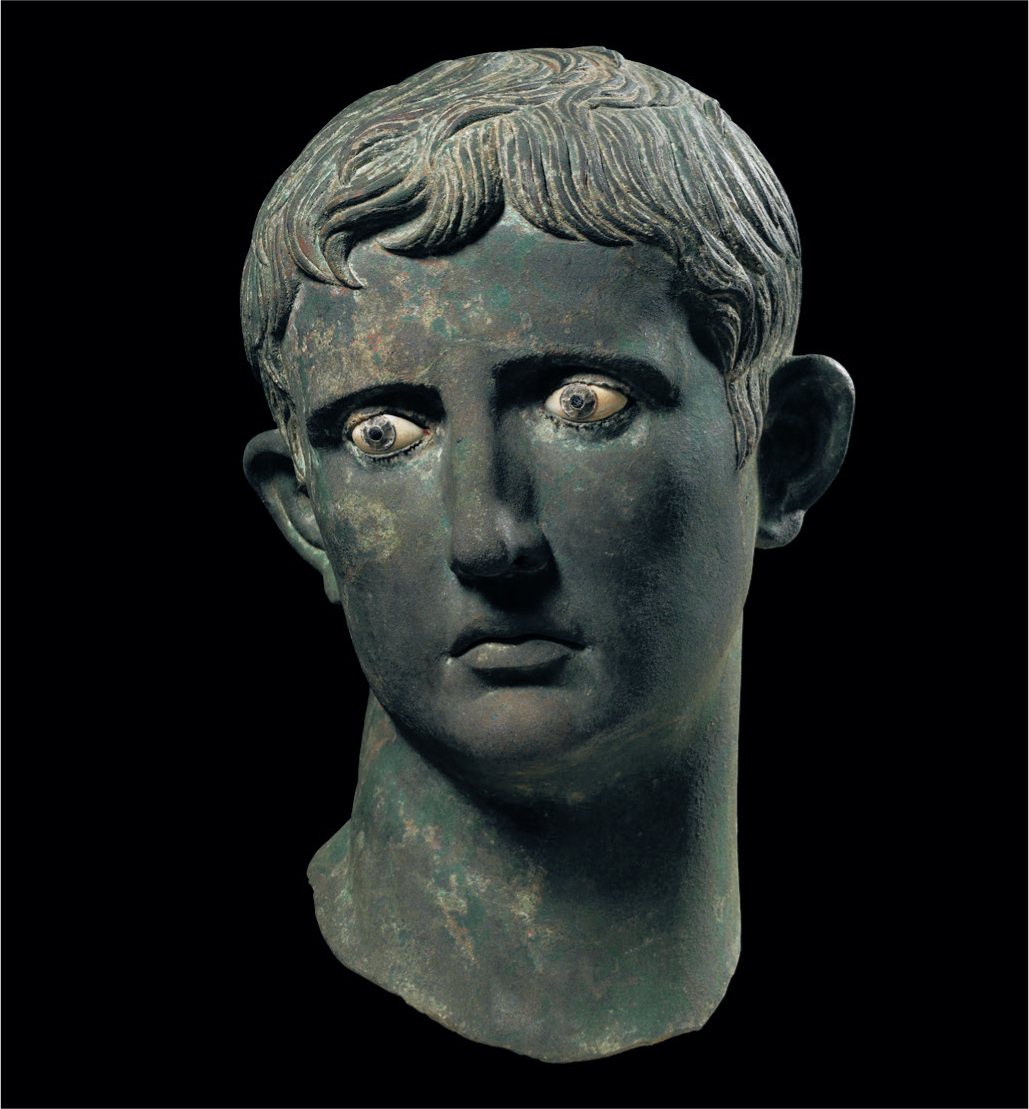

That said, there are some significant differences between images of Caesar and those of later emperors. Their identification has not always proved quite so difficult. A few sculptures have actually been found with names attached, and others in contexts, such as the dynastic group at Pantelleria, that drastically narrow down the options of who is who;47 and the far greater number and variety of surviving coin portraits offer a wider basis for comparison than anything before. There are also many more examples to work with overall. His successors often went far beyond Caesar in the mass dissemination of portraits. The guess that there were originally between twenty-five thousand and fifty thousand portraits of Augustus to be found across the Roman world may be too generous. But one reliable index of quantity comes from inscribed pedestals. Just over twenty survive that once held an image of Caesar; there are over two hundred that held an image of Augustus, at least a hundred and forty of them put up during his life (a long one, to be sure, but the underlying point remains).48

2.9 The ‘Meroe head’ of Augustus, so-called after the Kushite city of Meroe in modern Sudan where it was found. Complete with its original inlaid eyes, it almost certainly once belonged to an over-life-size bronze statue of the emperor, erected by the Romans in Egypt, raided by the Kushites and taken back as a trophy to Meroe. In the early twentieth century, it was excavated by British archaeologists and taken to the UK. The calm classical features of the portrait should not obscure the complicated stories of empire and violence that now lie behind it.

There are clear signs that, after Caesar, ‘getting the imperial image out’ became a highly centralised operation. Even when they are discovered hundreds or thousands of miles apart, some of the surviving imperial portraits are very closely similar to each other, right down to (or especially in) such tiny details as the precise arrangement of the locks of the hair (Figs 2.9 and 2.10b). For most modern art historians, the only way to explain the combination of such wide distribution and sometimes virtually identical portraits has been to imagine that models of the imperial face, probably in clay, wax or plaster, were sent out from the administration in Rome to the different parts of the empire, to be imitated by local artists and craftsmen, often in local stone. Some authorised prototype ensured that when Roman subjects, wherever they were, looked up at the statues in their distant hometowns, they all saw the same emperor.

2.10

(a) The head of Augustus from his statue at the villa of Livia at Prima Porta near Rome

(b) Diagram of the hair locks on an imperial portrait (based on the Prima Porta head, 2.10a)

(c) Head usually identified as Tiberius, Augustus’s successor

(d) Caligula depicted closely on the model of his predecessor Tiberius

(e) Head variously identified as Augustus, Caligula and two chosen heirs of Augustus, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, who died young

(f) Head variously identified as Augustus, Caligula, Gaius Caesar and Nero (and possibly re-cut to give it different identities)

There is actually not a shred of evidence for these prototypes, no trace in the Roman record of those who might have designed, made or dispatched them and no clue to the identity of the artists who used them to produce the finished sculptures. And they cannot possibly account for the wide variety of independent images, empire wide, that were intended to represent the emperor. Not everything was ‘top down’, or ‘centre out’. The moulds for imperial biscuits were surely not based directly on any template dispatched from Rome, nor were the splendid carvings of the emperor in the guise of an Egyptian pharaoh, nor all those rough-and-ready paintings that Fronto reported seeing (Fig. 2.11). Nonetheless, the logic that some such regulated process of copying lies behind some of the similarities in some sculptures is almost inescapable, and has obvious consequences for how imperial faces are recognised.

2.11 On the walls of the Egyptian temple at Dendur, built c. 15 BCE, Augustus several times appears in the guise of a pharaoh. Here, on the right, in an image that was once brightly painted, he offers wine to two Egyptian deities. In the cartouches (oval frames) next to his head he is named in hieroglyphs as ‘Autokrator’ (emperor) and ‘Caesar’—making this a much firmer identification than almost any of his Greco-Roman style portraits.

Over the last hundred years or so this has provided not so much a new method for identifying the portraits of emperors, but a new weapon in the traditional armoury of comparison. Many faces have been pinned down on the basis of tiny diagnostic details, which suggest that they derived from the same centrally produced model. At its most extreme, there can be something even more absurd about all this than the fuss over Caesar’s neck and his Adam’s apple: everything can rest on the tell-tale pincer formation of the curls above the statue’s right eye, for example, and almost nothing on what the sculpture actually looks like overall. But it means that, while barely a single head of Julius Caesar has gone unchallenged, combining the ‘absolutely certain’ identifications with the ‘very probable’, there are now a total of around two hundred surviving portraits of Augustus (who leads the count), and even twenty for young Alexander Severus.49

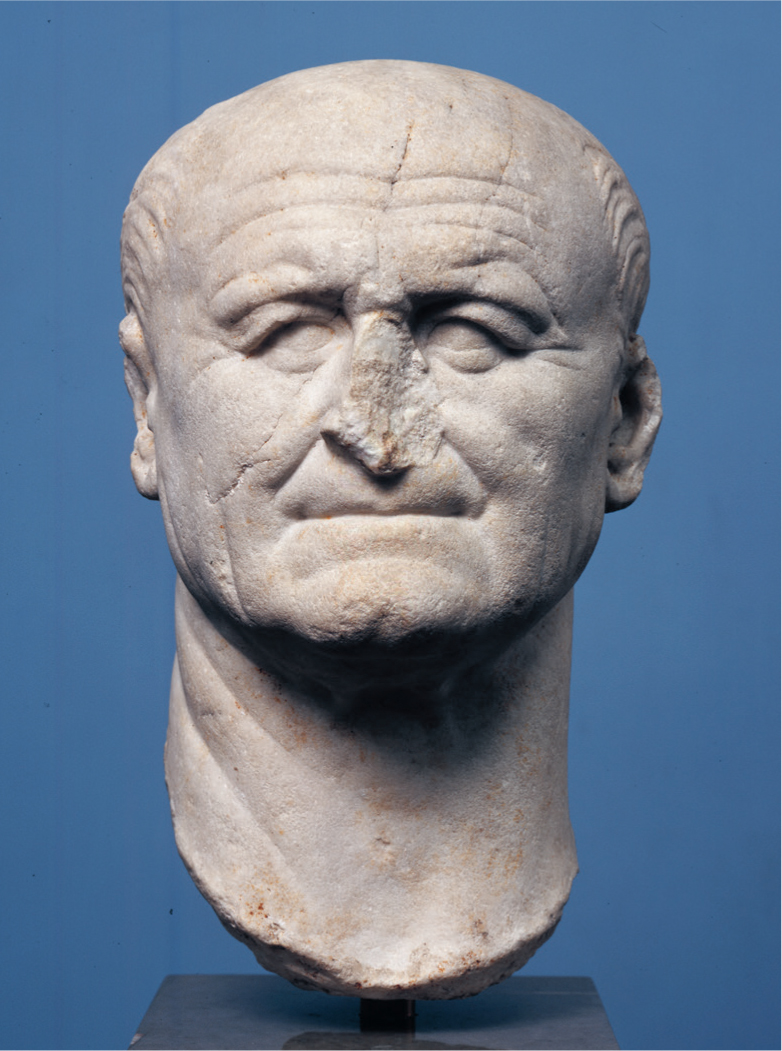

2.12 The down-to-earth style and decidedly middle-aged appearance of this head of Vespasian marks a—no doubt intentional—contrast with the youthful perfection of images of the previous, Julio-Claudian, dynasty.

This does not mean that all the Roman rulers following Caesar have an equally distinctive ‘look’ in ancient or modern art: far from it. Among Suetonius’s Twelve, Nero—with his characteristic double chin and sometimes the beginnings of a stubbly beard—regularly stands out in line-ups of marble busts almost as clearly as Julius Caesar; likewise, it is not hard to spot the almost impossibly perfect and youthful Augustus or the recognisably middle-aged, down-to-earth Vespasian (Fig. 2.12). But for modern viewers there are some frustrating mismatches between the emperors who are most memorably described in literature—Caligula, for example—and their rather bland representations in marble. Leaving aside the details of the hairstyle, some of Caesar’s immediate successors (especially if you include the penumbra of heirs and princes) really do look confusingly indistinguishable. To understand this, we must turn to other innovations at this period and to the politics behind them: a brand-new style of portraiture introduced with Augustus and a radically new sense of the function of the portraits within the imperial dynasty. Carefully constructed similarity (as well as occasional difference) could be the whole point.

Caesar Augustus and the Art of Dynasty

Julius Caesar’s plans for the future, whatever they might have been, were assassinated with him. It was Augustus who established the permanent system, though sometimes fragile continuity, of one-man rule at Rome. Under the name of Octavian, this young man had had a notorious record of brutality and treachery in the fifteen years of civil war that Caesar’s assassination had sparked. But in one of the most astonishing political transformations ever, after his victory over his rivals, he re-invented himself as a responsible statesman, coined a respectable new name (‘Augustus’ means not much more, or less, than ‘revered one’) and proceeded to rule as emperor for more than forty years. He nationalised the army under his own command, he ploughed enormous sums of money into redeveloping the city and supporting the people, and he cleverly managed to get most of the elite to acquiesce in his de facto control of the political process, while disposing of those who did not. Every emperor afterwards included not just the name ‘Caesar’ but ‘Caesar Augustus’ in his official titles: the assassinated dictator who stood at the origin of the Roman system of one-man rule was forever linked to the canny politician (‘the tricky old reptile’ as one of his much later successors called him) who devised the long-term plan.50

One major problem that the tricky old reptile never entirely solved, however, was the system of succession. It is clear enough that he intended his power to be hereditary, but he and his long-standing wife Livia had no children together, and a sequence of chosen heirs died at inconveniently early ages. Eventually Augustus was forced to fall back on Tiberius, Livia’s son by her first husband, who in 14 CE became emperor (hence the title ‘Julio-Claudian’ now given to this first Roman dynasty, reflecting its mixed descent from the ‘Julian’ family of Augustus and the ‘Claudian’ family of Tiberius’s father). Even when such practical difficulties were overcome, the principles of succession remained hazy. Roman law had no fixed rule of primogeniture; if you wanted to succeed to the throne, it certainly helped to be the eldest son of the ruling emperor, but it was not a guarantee. No natural son succeeded his father in the first hundred years of imperial rule, until Titus followed Vespasian onto the throne in 79 CE. It is hardly a coincidence that Vespasian was also the only emperor of the first twelve who is said, indisputably, to have died of natural causes. All the other assassinations, forced suicides or just the rumours of poisoning (unfounded though they may have been) point to the moment of succession as a moment of uncertainty, anxiety and crisis.

The ‘look’ of the new brand of imperial portraits is inseparable from this new political structure and had very little to do with the personal traits of Augustus himself. The description in Suetonius is one of the give-aways on that; the portraits at least do not have the irregular teeth, hook nose and knitted eyebrows that the biographer picks out as the emperor’s distinguishing features. Even more telling is the slightly icy perfection of the image, which was derived directly from statues of the classical age of fifth-century Greece, and the glaring fact that the portraits made through all forty-five years of the reign were close to identical, from his bronze head found in Sudan, the loot from a local raid on the Roman province of Egypt (Fig. 2.9) to his statue found on the site of Livia’s villa outside Rome (Fig. 2.10a). It is almost Dorian Gray turned upside down: in Oscar Wilde’s novel, the portrait ages while its subject remains youthful; in the case of Augustus, right up to his death in 14 CE in his late seventies he was still being depicted as a young man. To us, it may well seem rather blandly idealising, and we look in vain for any sign of that personal, dynamic relationship between sitter and subject sometimes taken, over-romantically perhaps, to be the touchstone of the greatest modern portraiture (in this case, the sculptors had probably never met their subject). But in the history of Roman self-display, where warts and wrinkles had previously been the common currency, this youthful, classicising image was shockingly innovative; a style unprecedented in Roman art was designed to embody the emperor’s unprecedented new deal, and his break with the Roman past. Far from being routinised, uninspired, government-issue work, this image of Augustus was one of portraiture’s most brilliantly original and successful creations ever. Intended to ‘stand in’ for him among the vast majority of the inhabitants of the Roman Empire who would never set eyes on him in person, it has ‘stood in’ for him ever since.51

TABLE 1

Table 1 Dynasties often trade on complexity; their multiple adoptions and remarriages are almost impossible to represent clearly on one page. This table is an intentionally simplified family tree of the Twelve Caesars, focussing on the main characters featured in the book.

It also set the standard for the portraits of his successors over the next centuries. Whatever the glimpses of individuality we may catch in Claudius’s slightly piggy eyes, Nero’s jowly double chin, or later in Trajan’s neat fringe, or Hadrian’s bushy beard, the emperors’ public portraits were about identity in the political, rather than the personal, sense. They were also about incorporating their subject into the genealogy of power and legitimating his place in the imperial succession. They provided a diagram of both the continuity and sometimes the ruptures in the right to rule. Through the tortuous family complexities of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (and later dynasties followed a similar pattern with a roster of bearded look-alikes in the second century CE), chosen successors were marked out by their sculptural similarity to the ruling emperor they were intended to replace—and by their similarity to the image of Augustus, back to whom the hereditary right to imperial power was traced.

It was not a series of absolutely identikit images: Tiberius can appear slightly more angular than Augustus (Fig. 2.10c), Caligula a little softer (Fig. 2.10d). But the general principle was that portraits were designed to make the emperor look the part, and for the first imperial dynasty looking the part meant looking like Augustus. Indeed, the biggest scholarly debates and disagreements around the identification of these Caesars have focussed not (as with the controversial pair in Pompeii) on whether a particular portrait is a member of the imperial family at all, but on which particular Julio-Claudian prince, princeling or short-term heir it is. Even the precise layout of the curls is not always up to producing a consistent answer. One delicate marble head in the British Museum, for example, has been identified as Augustus himself, as two of his short-lived heirs and as Caligula (Fig. 2.10e). An even more puzzling sculpture, in the Vatican, has been claimed for Augustus, Caligula, Nero and another of the would-be heirs (not to mention the possibility that it might be an Augustus later re-carved into a Nero, or even a Nero re-carved back into an Augustus) (Fig. 2.10f).52 It is hard to resist the conclusion that a perverse amount of scholarly energy has sometimes been devoted to drawing a fine line between subjects who were always intended to look the same.

That commitment to similarity inevitably alternated with a commitment to difference. After the fall of Nero and a year of civil war between 68 and 69 CE, the new dynasty of emperors—the ‘Flavians’, after its founder Flavius Vespasianus—was installed, and portraiture changed with the politics. Vespasian, as he is now usually known, adopted a ‘warts and all’ style, in contrast to the idealising perfection of the Julio-Claudian ‘look’. In general, the new emperor emphasised his down-to-earth approach to imperial power, his no-nonsense family background in a decidedly unfashionable part of Italy and his hard experience as a soldier. It was he, for example, who according to Suetonius put a tax on urine, a vital ingredient in the Roman laundry industry (hence the name ‘Vespasiennes’ for the old street urinals in Paris); and he cannily—if apocryphally—remarked that ‘money doesn’t smell’. His portraits too were obviously intended to play to assumptions of what down-to-earth realism looks like (Fig. 2.12). But there is no reason to suppose that they were any less a political construction than those of Augustus. In an attempt to exploit old-fashioned Roman tradition, he was carefully marking the visual distance between himself and the excesses of his predecessor Nero and the specious classicism shared by Augustus and his heirs. And that is how he has survived, been recreated and embellished, for two thousand years in the artistic imagination.53

What constitutes a ‘likeness’ has always been one of the big questions of art history and theory, from Plato to Ai Weiwei. There is always a debate about what exactly is (or should be) represented in a portrait: a person’s features, their character, their place in the world, their ‘essence’ or whatever.54 But our realisation that imperial portraits from Augustus on were largely focussed on political rather than personal identity was not shared by modern artists, historians and antiquarians before the twentieth century. They were aware of how disconcertingly youthful and idealising some of these images seemed (a feature that was sometimes explained away by the ‘vanity and the arrogance’ of the imperial subjects55). But their usual assumption was that not far behind all these ancient heads, the physical contours of real rulers, real persons and real personalities lay.

So indelibly real did they seem that, from the late sixteenth century on, imperial portraits were regularly used as accurate scientific specimens of people from the past, in a way that went far beyond the detection of the deformities of Caesar’s skull in the Tusculum head. There are some unexpected twists in this tale.

The Skull of Vitellius

Galba, Otho and Vitellius are three emperors who have not so far played a part in this chapter. This now half-forgotten trio ruled for just a few months each, before being assassinated or forced to suicide, during the civil wars in 68–69 CE that separated the Julio-Claudian dynasty from the Flavian. Suetonius’s picture of them is vivid, characterful but fairly one-dimensional: Galba, the elderly miser; Otho the libertine with a loyalty to Nero; Vitellius the glutton and sadist. Their ancient portraits have not recently claimed the kind of attention from art historians that those of Caesar or Augustus have attracted. In fact, despite several references—particularly in military contexts—to images of one contender for power being destroyed and replaced by those of another, it seems improbable that any of them during their brief moments of power, in the middle of civil war, would have had the time or resources to devote to circulating full-scale busts in marble or bronze; and they are not very likely candidates for posthumous commemoration. But earlier generations of scholars and artists (and even a few in recent years), wanting to complete a full line-up of Twelve Caesars, have looked for plausible heads to fill the gap between Nero and Vespasian.56

2.13 A portrait bust now in the ‘Room of the Emperors’ in the Capitoline Museums is identified as Otho, who ruled briefly in the civil wars of 69 CE, largely on the basis of what appears to be a wig (which Suetonius mentions that he wore). Otho was a friend and supporter of Nero, and—if he is correctly identified—a Neronian style may be reflected here, in contrast to Fig. 2.12.

The heads on coins and the descriptions in Suetonius again played the key part. Every Roman emperor, no matter how short his reign, issued coinage, because he needed ‘his’ cash to pay ‘his’ soldiers; and Suetonius picked out a useful detail or two here and there. Otho’s wig to cover his baldness (a throwback to Julius Caesar), or the elderly Galba’s hooked nose, were just about enough to recreate a plausible, if speciously convincing, ‘look’—and even to point (wrongly or not) to an ancient bust or two to fit the bill (Fig. 2.13).57 Vitellius was a special case—because of that distinctive head, the Grimani Vitellius (Fig. 1.24), discovered supposedly in excavations in Rome in the early sixteenth century, and apparently such an exact match for some of the images of the emperor on coins that it was taken to be a unique image of him ‘from the life’.

Perhaps the most recognisable and replicated of all imperial portraits, its fame went far beyond Veronese’s Last Supper and images of drawing lessons. As we shall see, this Vitellius has a cameo role in Thomas Couture’s vast reflection on Roman imperial vice and scarcely disguised allegory for contemporary French corruption, The Romans of the Decadence (Fig. 6.18); and it was the model for the corpulent, and rather wooden, emperor watching the gladiators in one of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s spectacular reconstructions of the amphitheatre, Ave Caesar! (Hail Caesar!). One copy of a copy of it, still on display in Genoa, is part of an extraordinary nineteenth-century pastiche, being embraced by the ‘Genius of Sculpture’ itself, as if it stood for the highest achievement of the sculptor’s art (Fig. 2.14).58

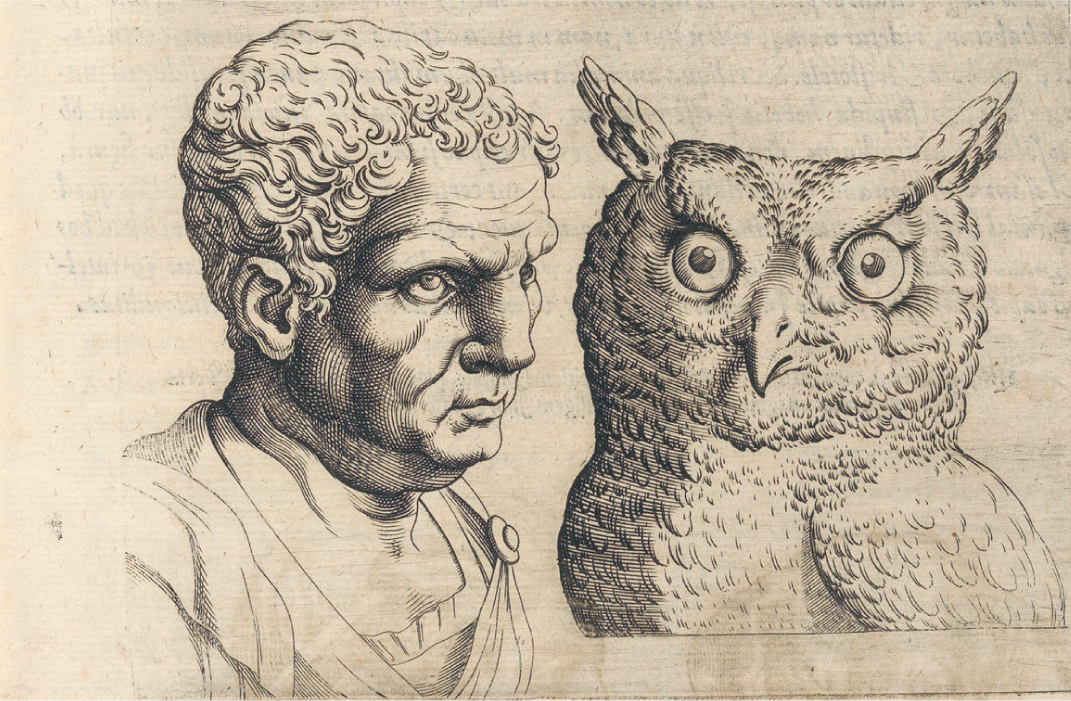

But, for many modern observers, there was more to this portrait than mere ‘art’. It was frequently used as a key example in those early scientific disciplines which read human character from external appearance: physiognomics, a discipline going back to antiquity itself, which claimed to be able to deduce temperament from facial features, often comparing humans to animal types; and phrenology, especially fashionable in the early nineteenth century, which claimed much the same from the shape of the skull (and so the shape of the brain within).59

In one of the most famous and detailed modern textbooks on this subject, by the Neapolitan scholar Giambattista della Porta, first published in the late sixteenth century, Roman emperors feature in the illustrations of historical characters: they include a Vitellius, not unlike the Grimani, whose features, and the size of whose head, are compared to an owl to demonstrate his ruditas (uncouthness) (Fig. 2.15).60 Phrenology was often a showier affair, with an established place on the popular lecture circuit in Victorian Britain. In one of his celebrity lectures in the 1840s, Benjamin Haydon—painter, art theorist, bankrupt and an enthusiast for reading skulls—featured a comparison between the head of Socrates, as it had been (imaginatively) re-created in ancient sculpture, and the head of the emperor Nero, predictably to the disadvantage of the latter.61 At roughly the same time, David George Goyder, a phrenological ideologue and eccentric enthusiast for a number of other lost causes (he was a minister of the Swedenborgian Church and staunch advocate of Pestalozzian education) went one better. According to a newspaper report of one of his lectures in Manchester, after an attack on the vested interests of establishment religion in their opposition to his new science (lining up Socrates and Galileo among others in its support), and an explanation of the basic system by which different parts of the brain were the seat of different talents and temperaments, the pièce de resistance involved a demonstration of his methods, complete with visual aids and, I imagine, all the razzmatazz he could muster. Among these was a ‘head of Vitellius’, whose skull, Goyder explained, was ‘round and narrow, not high’ indicating ‘an irascible, quarrelsome, and violent disposition’.62 He produced on stage a cast of the Grimani Vitellius.

2.14 The early nineteenth-century sculpture celebrating the ‘Genius of Sculpture’, by Nicolò Traverso in the Palazzo Reale in Genoa. The delicate, youthful figure of ‘Genius’ embraces a modern version of the Grimani Vitellius—originally a marble bust, but that was removed for display elsewhere and replaced with the plaster cast currently on display. The ‘Genius’, in other words, now embraces a copy of a copy of the Grimani Vitellius.

It will by now come as no surprise that this famous image, despite its (chance) resemblance to some of his portraits on coins, had nothing to do with the emperor at all. After decades of recent debate along predictable lines (is the head even ancient?), the standard modern view has demoted it to ‘unknown Roman’ and, thanks to some tiny technical details in the carving, has given it a date of the mid-second century CE, almost a hundred years after Vitellius’s assassination.63 There is a combination of irony and absurdity in this story. The idea that what was probably the single most reproduced head of any emperor in modern art was an ‘emperor’ in quotation marks all along can hardly fail to raise a wry, ironic smile. And the picture of a nineteenth-century visionary (or, depending on your point of view, crackpot) demonstrating the truth of a pseudo-science with the help of a head of a misidentified pseudo-emperor is more than a little absurd. But that absurdity is itself testament to the extraordinary power of the face-to-face encounter with the rulers of ancient Rome that these portraits seemed to offer.

2.15 In Giambattista della Porta’s sixteenth-century treatise on physiognomics, the head of Vitellius is likened to that of an owl, pointing to his uncouthness (the similarities constructively enhanced by the drawing). Other emperors featured include Galba (his hooked nose compared to an eagle’s beak) and Caligula (for his distinctive sunken forehead).

It is a face-to-face encounter that, even more surprisingly for us, imperial coins offered too, despite their tiny size. Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, especially, these miniature heads were far more than aids to the identification of large-scale portraits, important as that has always been. The next chapter will explore some of the earliest encounters between the modern world and the image of the Roman emperors—treated as almost living presences in miniature form, to be collected, displayed, carried round in your pocket, copied onto paper and re-created on your walls.