VII

CAESAR’S WIFE … ABOVE SUSPICION?

Agrippina and the Ashes

In 1886, a year before he painted his first version of the undignified accession to the throne of the emperor Claudius, Alma-Tadema recreated another scene from the history of imperial Rome, also exposing the cruelty and corruption of Roman autocracy (Fig. 7.1). At first glance, you might take this to be one of his slightly dreamy re-creations of Roman domestic life. There are no soldiers in this painting, no men even—just a solitary lady reclining on a couch, gazing pensively at what might possibly be her jewel box.

A closer look shows that it is nothing of the sort. The lady is reclining in what can only be a large tomb: there are epitaphs fixed to the wall; clearly legible behind her is the abbreviation ‘DM’, short for ‘Dis Manibus’ (to the spirits of the departed)—a standard phrase on Roman memorials; and the stairway on the left hints that the scene is set underground; what might have been a jewel box is more likely a small funerary urn that she has taken down from the niche in the wall. The title of the painting identifies it precisely: Agrippina Visiting the Ashes of Germanicus. Alma-Tadema has, in other words, imagined a scene in the life of one of the Roman imperial family’s tragic heroines: Agrippina the Elder (as she is now called, to distinguish her from her daughter, ‘the Younger’).1

The story of her devotion to the memory of her husband Germanicus—whose statue surveyed the ‘decadence’ of Couture’s painting—was a favourite in ancient Rome.2 Writers lingered not only on the ghastly death of the dashing young man himself in Syria in 19 CE, widely believed to have been ordered by his uncle, the jealous emperor Tiberius; but also on the unswerving loyalty of Agrippina, who—as one of the very few direct natural descendants of the emperor Augustus—had an even better royal pedigree than her husband. She is supposed to have carried his ashes back to Rome, over almost two thousand miles, to a rapturous reception from the public (whose grief at Germanicus’s death has been compared to the modern outpouring of popular emotion at the death of Princess Diana3). Here Alma-Tadema pictures Agrippina alone on what must be a later visit to the family tomb; she has come to hold once more the ashes that had become her trademark or talisman. The name of ‘Germanicus’ can just be made out on the memorial plaque on the wall.

7.1 Agrippina, visiting the family tomb, cradles the box containing the ashes of her husband Germanicus, which she has taken down from the niche beside her. Alma- Tadema’s painting of 1886 captures an atmosphere of brooding domesticity at an intimate scale (it is less than forty by twenty-five centimetres).

Worse, however, was to come. In the standard story at least (the truth is another matter), Agrippina did not retreat into judicious, inconspicuous retirement. Instead, she stood up to Tiberius and to his apparatchiks in a series of displays of admirable principle, family loyalty or pointless stubbornness (depending on your point of view). Eventually, in 31 CE she was exiled to a tiny island off the coast of Italy, where she starved herself (or was starved) to death. It was only in the reign of her son Caligula—one of those imperial monsters devoted to their mothers—that her ashes were brought back to Rome. The large memorial stone in which these were then placed still survives, though with a twist in the tale. It was rediscovered and recycled for use as a grain measure in the Middle Ages, and only restored as an ancient monument in the seventeenth century and placed in the Capitoline Museums in Rome, where it still stands. (The Roman burghers in 1635 could not resist inscribing a tasteless joke on its new pedestal: there was a certain irony, they suggested, in constructing a measure for grain/sustenance (frumentum) out of the memorial of a woman who died by refusing frumentum.)4

Agrippina’s story and Alma-Tadema’s attempt to recapture the sorrowing widow in the tomb (not to mention the bluff ‘humour’ of the seventeenth-century Romans) raise some bigger questions about the role of women in the imperial family, and about their images ancient and modern. So far in this book, representations of the wives, mothers, daughters and sisters of the Roman emperor, have played only a minor part. There always have been, it is true, considerably fewer of them than of the emperors themselves, or of their brothers and sons. But some have gained celebrity status. A Roman bust of Faustina, the wife of the second-century emperor Antoninus Pius, for example, was the object of a famous early sixteenth-century tug-of-love between Andrea Mantegna and Isabella d’Este, who eventually managed to buy it from the cash-strapped painter for a knock-down price (though if this was the rather dreary bust Faustina still in the Ducal Palace at Mantua, it is hard to see what the fuss was all about (Fig. 7.2)).5 And Agrippina Visiting the Ashes of Germanicus is just one of many paintings where modern artists have used the figures of women to expose the corruption of the imperial court.

This chapter will explore the history of women in the imperial hierarchy, as part of the complex genealogy of the ruling house. There are some famous and not so famous names, from Augustus’s wife Livia (whose villainies gained new notoriety thanks to the actor Siân Phillips, who played her in the BBC/HBO series I, Claudius in the 1970s), to Messalina (Claudius’s third wife, rumoured in ancient Rome to have taken on a part-time job in a brothel) or Octavia (the virtuous first wife of Nero, whose fate was to watch her nearest and dearest drop down dead in front of her). But what did they really do? How important were they? And how were they depicted in visual images, ancient or modern? We have seen that the beginning of one-man rule went hand in hand with revolutionary changes in the representation of the new political leaders (emperors, princes and male heirs): was that the same for the women of the family? What do we gain by taking a female focus? We shall end by taking a closer look at Agrippina the Elder and the Younger: one an implacable martyr; the other, the wife of Claudius and mother of Nero who eventually becomes a gruesomely dissected corpse. And we shall be bringing yet another Agrippina to light in a famous, and controversial, painting by Rubens, which is my very last case of mistaken identity.

Women and Power?

There was no such thing as a ‘Roman empress’. It is almost impossible to avoid the term entirely (more than a few ‘empresses’ will, I confess, creep into the pages that follow). And various honours granted to the most important women at court, including the title ‘Augusta’, the female equivalent of ‘Augustus’, suggests some public prominence. Livia herself was the first of these: she was formally known as ‘Julia Augusta’ after her husband’s death (almost as confusingly, at the time, I imagine, as it is now), and she was earlier hyped in one ‘absurdly hyperbolic’ poem as ‘Romana princeps’ (which is not far short of ‘queen’).6 Nevertheless, poetic over-statement aside, there was no official position of imperial consort, and certainly no possibility of a woman occupying the throne herself. When we talk of the women of the imperial family we are referring to a motley, shifting crew of emperors’ wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, cousins and lovers, with varying degrees of influence and importance, but no formal position in the hierarchy.

That said, Roman writers treated these female members of the imperial family as much more powerful in practice than elite women had been in the earlier period of the Republic. How true that was is hard to determine. I strongly suspect that Livia, or any of the others, would have been amazed to learn of the influence attributed to them by writers ancient and modern, or the inconvenient rivals they are said to have liquidated (rumour, of course, flourished in a world where a deadly case of peritonitis was indistinguishable from a deadly case of poisoning). But true or not, that perception of female power goes back directly to the structure of one-man rule.

First, in any court culture like imperial Rome, influence is seen to lie with those close to the man at the top. It is the power of proximity, and it belongs to those who have the ear of the emperor, whether because they chat at dinner, shave his beard or (better still) share his bed. Up to a point, of course, there is power in proximity, and this is what drives the old cliché about women being ‘the power behind the throne’. But more than that, women are a wonderfully convenient explanatory device for the mysteries, inconsistencies and vagaries of the emperor’s decision-making; hence the exaggeration of their influence. The advent of autocracy meant that power moved away from the open discussion of the Republican forum or senate house, to the hidden corridors and secret cabals of the imperial palace. No one outside the palace walls really knew how—or by whom—decisions were made inside.7 Blaming the influence of wife, mother, daughter or lover was a convenient catch-all explanation (‘he did it to please Livia’, or Messalina, or Julia Mamaea, or whoever). Modern media sometimes resort to the same device when trying to explain the inner workings of the White House, 10 Downing Street or the British royal family (think Ivanka Trump, Cherie Blair or Meghan Markle).

7.2 This Roman bust, just under life-size, may (or may not) be the portrait of Faustina, wife of Antoninus Pius (emperor 138–61), over which Isabella d’Este and Mantegna fought in the early sixteenth century. Whether she is correctly identified or not, the hairstyle is one of the stylistic features that date the portrait to the mid-second century.

But in Rome this was also linked to the centrality of women in the strategies of dynastic succession. To put it at its simplest, their crucial role in producing legitimate heirs underlies the two dramatically different female types that dominate ancient writing and imagination. On the one hand, were those who acted correctly within the dynasty, bore children loyally and facilitated the transmission of power. On the other, and much more prominent in the modern imagination, were the likes of Messalina or Livia, with their deadly skills at poisoning (the traditional female crime: secret, stealthy and domestic, a fatally perverted form of cookery). Their behaviour threatened to disrupt orderly succession, whether through adultery or incest—or through a dangerous partiality for their own offspring within the pattern of succession, and the single-minded elimination of any rivals.

TABLE 2

What this means is that the accusation of gross sexual immorality often thrown at the women of the imperial family may reflect what they got up to, but not necessarily (most people at the time had no more reliable information on Messalina’s sex life than we do). It certainly does reflect one of the ideological pressure points in the Roman imperial dynasty, as in many similar patriarchal structures: namely, how to regulate the sexuality of those whose purpose it was to bear legitimate heirs, and the anxiety on the emperor’s part (in an era in which you could never know for sure) that ‘his’ children might not really be ‘his’. It was a pressure point given extra charge by the fact that no natural son did actually succeed his father, for more than a hundred years of Roman imperial rule. Vespasian was not only the first emperor universally agreed to have died a natural death, in 79 CE; he was also the first emperor to have his natural son succeed him.8

These anxieties underlie the famous quotation, now almost a proverb, which I have adapted for the title of this chapter, ‘Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion’.9 The origin of this lies in an incident early in Julius Caesar’s career, when he was still an ambitious young politician, a couple of decades away from being dictator at Rome. His then wife Pompeia was conducting a special religious ritual, rigidly restricted to women only, when a man was reported to have infiltrated the gathering. The rumours were that it was a lover’s prank, and that the man in question was having an affair with Pompeia. Caesar claimed that he himself did not suspect her, but he divorced her nonetheless, because Caesar’s wife must be ‘above suspicion’.10 Similar anxieties also underlie, in a more ambivalent way, the competing stories about the death of Augustus. One lurid version we have already seen was that Livia finished him off, by smearing poison on the emperor’s favourite figs as they grew on the trees (‘by the way, don’t touch the figs’, as the television Livia memorably warned her son Tiberius). The other, recounted by Suetonius, insisted just a little too hard perhaps, and almost parodically, on the conjugal devotion of the imperial couple: he dies while kissing his wife and simultaneously managing to say, ‘Live mindful of our marriage Livia, farewell …’.11

What really happened on the deathbed of Augustus is entirely lost to us (and there is no particular reason to believe either of these colourful tales). But the contradictory accounts of the scene in Roman writers point straight at the dilemmas about imperial death, succession and the potentially disruptive role of women within the structures of power. In some ways the representations of ‘empresses’ in official Roman art is in dialogue with those anxieties.

Sculptures, Great and Small

There are plenty of women from the imperial family in our galleries of Roman portrait statues, and plenty of evidence for more that we have lost (recorded, for example, on statue pedestals now minus their statues). But it is even harder than with their husbands, brothers and sons to pin down exactly who is who. These images are no less revolutionary than their male counterparts, indeed probably more so. The new politics of empire dramatically influenced the style of the portraits of men at the top. Autocracy and dynasty put women on display in the repertoire of public sculpture for the very first time, initially as part of the diagram of imperial power, and then more widely. Before the early years of one-man rule there was no established tradition in Rome itself of honouring real-life, mortal women with public statues (it was different with goddesses and in other parts of the wider Roman world).12 But identifying who was who, with any certainty, proves to be extremely hard.

The basic difficulty, as with the men, is that only a handful of these portraits come complete with a name; and there is no scientific method for establishing their identity. But that is only the start. Important as the statues of women were in spreading the image of the ruling family across the empire, there were always fewer of them than of the men. Certainly, fewer survive: some ninety portraits of Livia, for example, even on a generous count, versus the two hundred or so of Augustus. There is, in other words, less material to compare and contrast.

What is more, there are even fewer external criteria to provide any kind of benchmark. In identifying the men, matching up the portraits with the heads on coins or with the descriptions of the emperor’s features in Suetonius has proved treacherous (a miniature image is hard to align with a full-sized sculpture, a colourful description in Suetonius hard to square against white marble). But it is at least something—and in the case of the women we can hardly attempt even that. The heads of imperial women do appear on Roman coins, but much less frequently than the emperors themselves,13 and Suetonius does not systematically describe the appearance of the wives and daughters as he does of the men in power. Context and find-spot can help, particularly in the case of groups of imperial portraits. The representation of Livia, for example, a few steps behind Augustus, on the sculptured frieze of the famous ‘Altar of Peace’ in Rome, raises few doubts.14 But even in some of these groups, the women’s almost identical bland classical features can still prompt endless debates about who exactly they were intended to be. A trio of imperial ladies on public display at the town of Velleia in north Italy illustrates that point perfectly. We can be fairly certain, partly on the basis of inscribed plinths found on the same site, that we are dealing with a Livia and two Agrippinas, Elder and Younger; but to the average viewer (and I am not sure the specialist can really do any better) they might as well be identical triplets (Fig. 7.3).15

7.3 Three imperial women from a group of thirteen surviving imperial statues, slightly over life-size, that once stood in one of the public buildings of the small Roman town of Velleia in north Italy. There is some evidence, in the words inscribed on the surviving plinths, of how these statues are to be identified, but almost more important is how similar they look: (a) Livia; (b) Agrippina the Elder; (c) Agrippina the Younger.

For the most part, the women’s hairstyles give the surest guide, at least to the date of the sculpture, and so also to the possible pool of candidates. There is much less of the, sometimes spurious, precision in the exact layout of the locks of hair, which has played so large a role in identifying their male counterparts.16 It is more a question of the overall character of the coiffure, which changes over time, from the modestly flat hairdos of the early first century CE to the elaborate piles seventy years later, under the Flavian dynasty and later (Fig 7.2). But here another problem enters. The fact is that (unless some imperial context gives a clear steer) it can be impossible to know whether a particular portrait is one of the emperor’s female relatives, some rich private individual with the same fashionable hairstyle or someone consciously aping the appearance of the ‘empresses’.17

Similarity is the hallmark of the ‘empresses’. With the male members of the imperial dynasties, there was always a representational trade-off between similarity and difference. The look-alike Julio-Claudian princes were look-alike precisely in order to appear as indistinguishable as possible from the Augustus they were being marked out to succeed. Yet reigning emperors also needed recognisability, or in some cases—such as Vespasian—they needed to assert a strong form of difference from their predecessor. Hence, tenuous though ‘the look’ may sometimes be, there were, and continue to be, standard expectations of the appearance of a Julius Caesar, an Augustus or a Nero. Not so with the female members of the dynasty. Whatever the sharply drawn, colourful and conflicting stereotypes of the different characters in ancient literature, the official art of the Roman Empire (and any unofficial version of these women is lost to us) seems almost to have insisted on their bland homogeneity, even—hairdos apart—interchangeability.

This was not a failure of ancient sculpture or sculptors to distinguish between one woman and the other. Whoever the artists of the finished pieces were, the chances are that they never saw these women face to face anyway (no more than they would have seen the emperors and princes), but that they were working from some kind of model sent out from Rome. Once again, who—if anyone—controlled the process is a mystery. It would be implausible, given what else we know about how things were done in the imperial palace, to imagine that the emperor and his advisers sat down and took the decision that all the women of the family should henceforth be depicted alike (or, as sometimes seems to happen, especially in the later empire, that the women’s features should be made to match their husbands’18). Yet, however it was achieved, the similarity was the point. It acted as an antidote to the potentially disrupting effects of the demands, desires and disloyalties of the individual women in the political hierarchy that were such a prominent part of the Roman literary imagination. These repetitive images asserted their role not as individual agents, but instead as generic symbols of imperial virtues and dynastic continuity. That was backed up by other aspects of their portraits.

7.4 A miniature portrait of a woman, on an ancient cameo, just under seven centimetres tall (the frame is an addition of the seventeenth century). It was most likely made for, and depicts, a member of the ruling house, but there is debate about exactly who she is, and who the children are. Messalina with her son and daughter, Britannicus and Octavia, are very strong candidates.

One of those aspects is encapsulated in a miniature image on a Roman cameo, which ended up (complete with a new seventeenth-century frame) in the collection of the French kings, having once been owned by Rubens, who produced a drawing of it (Fig. 7.4). The preciousness and cost hint at a very close connection between cameos such as this and the ancient imperial court, whether they were palace décor or diplomatic presentation pieces (these are quintessentially royal objects). But the exquisite appearance and the extraordinary skill needed to create portraits of this type—involving an intricate process of cutting away the precious stone to reveal different colours for different parts of the design, on a tiny scale—can cloak some of the oddities and complexities of meaning.

For a start, we find the same old problems about the identity of the artists and the models they used (most are unknown) and the identity of the subjects (most are debated). Here the woman has been variously identified as Messalina, Agrippina the Younger, Caesonia the wife of Caligula and Drusilla his sister. It is, however, the logic of the design that counts most, whoever it was originally intended to be. For behind the woman, a cornucopia (horn of plenty) not only brims with fruit (a common symbol of richness and fecundity in ancient art) but out of the top, slightly incongruously, peeps a young child—probably a boy, though later re-cutting makes it hard to be absolutely certain, even with the help of Rubens’s, perhaps not wholly accurate, drawing. Another figure, traditionally seen as a girl, nestles at the woman’s other shoulder.19

Assuming the child in the cornucopia is male, this is an assertion of fecundity not in the sense of fruits of the field, but in the sense of producing an heir to the throne. It might seem unsurprising to herald the ‘empress’ as mother, and there are many other Roman examples, great and small, that parade exactly that role. But there is very likely more to it in this case. Let’s suppose that the woman is Messalina (which remains a standard view, though the identity of the mother partly depends on what sex we decide the children are, or whether the lower one is a child at all). If so, then this image is not only about as far from the satire of ‘empress-as-prostitute’ as you could imagine, but is almost an attempt to foreclose on any such idea, emphasising instead the image of the imperial woman as guarantor of male succession: no more and no less.

It is only with the benefit of hindsight that we realise that this particular succession would not turn out as well as it promises. For, if Messalina is the mother, then the little boy himself, emerging from the cornucopia as the hope of the dynasty, must be Britannicus, the emperor Claudius’s son, who conveniently dropped down dead at dinner in his early teens, so ensuring that he could offer no threat to his stepbrother Nero’s place on the throne. The Roman historian Tacitus implied that you might have thought that the death was from natural causes, except for the awkward fact that the funeral pyre had been prepared in advance.20

The presentation of ‘empresses’ in the guise of goddesses was another way of inoculating the visual realm against the supposed dangers of female power, agency and transgression. There were all kinds of overlaps in the Roman imagination between the power of the gods and the power of emperors; and, in one of the most puzzling elements of ancient religion for a modern audience (referenced in Charles I’s gallery of paintings and parodied on that staircase at Hampton Court), some emperors, as well as some of their female relatives, were officially recognised as divine, with temples, priests and worship, after their death.21 But during their lifetime, the male members of the family were more often represented in iconic human roles (as general, orator and so on). It was much commoner for ‘empresses’ to be given the appearance of goddesses—or, more accurately, their statues regularly combined the facial features associated with imperial women, and the clothing, attributes and stance of goddesses.

7.5 There was a fuzzy boundary between images of goddesses and images of the women of the imperial family. Here (a) a full-sized statue of (probably) Messalina with a child draws on (b) a famous classical Greek statue of the goddess ‘Peace’ holding her child ‘Wealth’ (seen in a later Roman version).

So, for example, a full-scale statue often identified, rightly or wrongly, as Messalina, again with the baby Britannicus (Fig. 7.5), actually apes the pose of a famous fourth-century Greek sculpture of the goddess Peace (Eirene) holding her child Wealth (Ploutos)—partly exploiting the same conceit as in the cameo, by substituting human prosperity, in the shape of a child, for material prosperity in the shape of cash or crops.22 Even more striking is one of the sculpted marble panels from the most important assemblage of Roman sculpture unearthed in the twentieth century. Hundreds of miles away from Rome, in the small town of Aphrodisias in what is now Turkey, these panels—dozens of them—once decorated a building, put up by a group of local bigwigs in the first century CE, in honour of the Roman emperor and his power. They celebrated a variety of successes and dynastic moments in the history of the Julio-Claudian family, and one is generally agreed to depict Agrippina the Younger crowning her son Nero as emperor (Fig. 7.6).23 Her face and hairstyle fit reasonably well with other so-called Agrippinas. But her pose, dress and that cornucopia again clearly blended with familiar ancient representations of the goddess Ceres, the goddess who—among other things—protected crops, harvests and productivity more generally.

7.6 On a first-century monument celebrating the Roman imperial family in the ancient city of Aphrodisias in modern Turkey, one of many sculptural panels (more than a metre and a half tall, but placed so high up that details would have been hard to make out from the ground) depicts Agrippina the Younger—or is it the goddess Ceres?—crowning the emperor Nero.

Many modern observers have taken this blending of mortal woman and immortal goddess for granted, with a disappointing lack of puzzlement. Museum labels and photo captions tend to read laconically, ‘Agrippina as Ceres’, or ‘Livia in the guise of Vesta’ or whatever, without facing the question of what that ‘as’ or ‘in the guise of’ really means. Are we meaning these empresses were dressed up as goddesses, adopting a convenient artistic template for the public display of a woman? Or is it that they were imagined as super-human figures, whether in a subtle metaphor of female power or in a strong and literal assertion of the empress’s divinity? Or is it the other way around? Was the audience meant to see ‘Ceres as Agrippina’, ‘Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, in the guise of Livia’?24 These are questions of sculptural identity with a new spin: not, ‘Is it Agrippina the Elder or the Younger’, but ‘Is it Agrippina or the goddess Ceres’?

There is no single right answer here. One observer’s clever visual metaphor may always be another’s plodding equivalence between empress and goddess. But this convention was another means of dulling the individuality of these women in the imperial family, and mitigating the risk of their prominence. The sculptural vignette of the coronation of Nero shows how this works. Whether or not you believed the lurid rumours of Agrippina engineering Nero’s path to the throne (including the famous poisoned mushroom trick to dispose of her then husband Claudius), it would be unthinkable in Roman terms to imagine a mortal woman publicly honoured for securing the imperial succession of her son. The figure of Ceres, by overlaying Agrippina, effectively conceals any hint of mortal agency in the dynamics of succession, transferring it to the level of the divine (even if a few cynics might still have shaken their heads). To put that more generally, blending the figures of empress and goddess was both a gesture of honour to the imperial woman concerned, and at the same time a strategy for effacing her individuality and worldly power.

Mothers, Matriarchs, Victims and Whores

These two very different images of imperial women—the carefully contrived lack of individuality in official visual arts on the one hand, and the colourful, sometimes counter-cultural literary tradition on the other—have left their mark on modern representations.25 For a start, it has proved next to impossible ever to create a convincing line-up of Twelve ‘Empresses’ to match the Twelve Caesars. It is true that a number of female relatives sit alongside the emperors in the Room of the Emperors in the Capitoline Museums, and in the overall design of the Camerino dei Cesari at Mantua some of the dynastic gaps between the generations were filled with small roundels of the emperors’ wives and mothers. But there is no Suetonius to define anything like an orthodox set of imperial women; even if you restrict the focus to the wives only, there are many more empresses than emperors (almost every emperor married several times); and, apart from those changing fashions in hairstyles, there is no ancient ‘look’ to distinguish one from another. The familiar modern groups of the Twelve Caesars, whatever their fuzzy edges, substitutions and misidentifications, are usually exactly that: Caesars only.

Occasionally an adventurous modern artist did attempt a series of empresses to parallel the men, whether out of a sense of symmetry, completeness or maybe a desire to introduce an erotic touch to the otherwise austere imperial landscape. But it was less easy than it must have seemed. The problems become clear in the most famous and influential such series to have survived, from the hand of the engraver Aegidius Sadeler in the early seventeenth century. For Sadeler did not stop with his twelve emperors, and their—part bitter, part cheeky—accompanying verses. He also produced twelve matching imperial women to make a complete set of twenty-four, in couples (Fig. 7.7).

Sadeler’s source of inspiration for this has long been a puzzle. There is no original artist named on the prints of the women (unlike the acknowledgement to Titian as ‘inventor’ on those of the men—including, wrongly, Domitian). So did Sadeler devise them himself, in order to get both sexes in? Or, if he copied them, where were, or are, the originals? There have been all kinds of suggestions. But finds in the archives at Mantua and elsewhere make it now virtually certain that these figures ultimately go back to a set of imperatrici (empresses) painted in the 1580s by a local artist, Theodore Ghisi, to complement Titian’s Caesars—and installed in their own room, the ‘Camera delle Imperatrici’, somewhere in the palace.26 How this was laid out, even where exactly it was, and what happened to the paintings (or to the versions of them, which might have been Sadeler’s immediate source) is largely a matter of guesswork. There is certainly no sign that they were ever part of the negotiations that brought the other ‘Mantua peeces’ to England. All we now know of them comes from the prints.

7.7 In the early seventeenth century, Aegidius Sadeler produced prints of twelve ‘empresses’ to match his emperors. Much less familiar as household names, they are in order of their twelve imperial husbands: (a) Pompeia; (b) Livia; (c) Vipsania Agrippina; (d) Caesonia; (e) Aelia Paetina; (f) Messalina; (g) Lepida; (h) Albia Terentia; (i) Petronia; (j) Domitilla; (k) Martia; (l) Domitia Longina.

In some ways, they were a close match with the emperors. The women were shown as the same distinctive three-quarter-length figures, and in Sadeler’s versions they too have verses beneath, albeit slightly less hostile in general than those attached to the Caesars themselves (some of the most renowned imperial ‘villainesses’ got off lightly, more tragic mothers than whores).27 They were also replicated, in several series of frankly undistinguished oil paintings that have turned up all over Europe, and more appealingly in other media too. Their faces were included among the tiny enamels on that elaborate binding of Suetonius’s Twelve Caesars (Fig. 5.14); and the image of Sadeler’s Augustus on the royal teacup was matched by his Livia in the centre of the saucer (modestly concealed, or firmly obliterated, when the cup was in its place) (Fig. 7.8). But there were some telling differences too.

All but one of these women in their flouncy frocks look more or less identical, with none of the individuality—either in features or dress—of the corresponding emperors; it would be very hard to tell, say, Petronia (wife of Vitellius), from Martia Fulvia (wife of Titus), just on appearance. The verses sometimes only add to the confusion. In one case the writer was hopelessly muddled about who the woman depicted was, apparently imagining (wrongly) that Pompeia, Julius Caesar’s second wife who was supposed to be ‘above suspicion’, was the daughter of Caesar’s enemy Pompey.28 The fact that there was usually more than one wife to choose from and other marital complications (to put it euphemistically) only added to the problems. These complications lie behind the one and only distinctive character in the line-up. For the emperor Otho had had just one wife, early in his life, Poppaea, who later married Nero. Presumably in order to avoid the difficulties that this might cause in his set, the artist chose to omit Poppaea altogether, to depict a later wife of Nero (a different, but related, Messalina), and in the case of Otho to substitute his mother for a wife. Her standout appearance is simply down to the fact that she is represented as much older than the others.

It is almost as if the project to construct a series of twelve ‘empresses’ ended up exposing the fact that it was impossible to do so on the same terms as the men. It foundered on the routine similarity between them, on simple confusions about who was who, and on the lack of any distinctive ancient ‘look’, for the later artists to discover, follow or adapt. And the Sadeler prints (or the paintings lying behind them) were not the only case of this. Similar dilemmas, in even starker form, are found a century earlier in Fulvio’s compendium Illustrium imagines, with its series of numismatic-style portraits accompanying a brief biography of each of his famous Romans, both men and women. In one entry, that of Cossutia (who may have been married to Julius Caesar in his youth, so nudging Pompeia to third place), her life history is covered in a single sentence, but there is no image. In two others—‘Plaudilla’, probably the wife of the third-century emperor Caracalla, and ‘Antonia’, possibly the emperor Augustus’s niece—there is an image, but no biography. Whether or not this is an advertisement of scholarly probity on the part of Fulvio, a guarantee that he would not fill any gaps for which he did not have proper evidence or a tease about completing the collection (above, p. 134), it can hardly be a coincidence that all these gaps concern women. It is indeed instructive that in a slightly later, bootleg version of Fulvio’s book, a portrait of ‘Cossutia’ has been found to take the place of the blank. But it has nothing to do with Cossutia at all; it is actually a rather effeminised portrait of the emperor Claudius that has simply been borrowed, knowingly or ignorantly, for the purpose. A man here quite literally stands in for a woman.29

7.8 The saucer to go with the royal teacup decorated with Sadeler’s Augustus (Fig. 5.3), featured his image of Augustus’s wife Livia (though, in a wry comment about female invisibility maybe, you would not see her when the cup was resting on the saucer).

It was impossible for these modern artists to re-create a systematic authentic line-up of the Twelve Caesars in female form. But, beyond the gaps, uncertainties and identikits (and perhaps partly liberated by them), as far back as the Middle Ages, Western artists have enjoyed re-imagining the colourful tales of these women’s power and powerlessness. Like Alma-Tadema in his painting of Agrippina and the ashes, they have used and embellished ancient anecdotes, satire and gossip about them to expose the corruption of empire and the tragedies of its innocent victims. They have produced some brilliant, if chilling, re-creations of the dynamics of Roman autocracy, through a female lens, although with more than the occasional hint of misogyny. Their empresses appear in different guises, from sexual predators to blameless heroines.

Aubrey Beardsley’s versions of Messalina-as-prostitute are memorable late nineteenth-century attempts to re-imagine imperial vice. In one of these, the empress steps out into the night, her black cloak merging with the darkness, our attention turned onto her vampish feathered hat, brazen pink skirt and naked breasts (echoing one Roman satirist who picked out her ‘gilded nipples’ (Fig. 7.9)30). It is a disconcerting and slightly puzzling image. Is Messalina setting out for a night at the brothel, that grim look—which is shared with her menacing companion—hinting at their single-minded determination for sex? Or is she returning home to the palace of the cuckolded Claudius, frustrated that she has still not had enough? Either way, it is a picture of a dangerous sexual omnivore in the highest places, simultaneously exposing to ridicule the pathetically insatiable woman and, by implication, the inadequate and humiliated husband.31

In this art-nouveau style, which brings its own peculiar engagement with ‘decadence’, Beardsley was playing with a long tradition of such rampant Messalinas. She was a particular favourite of British eighteenth-century caricaturists, James Gillray and others, for whom she conveniently symbolised the grotesqueness of unchecked female sexual desire. To be honest, you sometimes have to look hard for her. In one of Gillray’s nasty satirical prints, pillorying Lady Strathmore for adultery with the servants, drunkenness, child-neglect and desertion of her husband (there was, needless to say, another side to the story), a picture of Messalina is pinned to the wall in the background.32 But she plays an even more telling cameo role in a mocking cartoon of an even better-known adulteress: Lady Emma Hamilton, who is depicted in her nightdress, ‘comically’ obese, watching in despair through the bedroom window as Lord Nelson’s fleet sails for France, while her elderly husband sleeps oblivious in the bed behind her (Fig. 7.10).33 On the floor is a careful selection from Sir William Hamilton’s precious collection of antiquities—including the head of a so-called Messalina, positioned between a broken phallus (equipped with feet and tail) and a naked Venus, into whose crotch she apparently tries to peer. Again, there are tricky questions here about what exactly we are laughing at (who is the biggest fool: Emma Hamilton, her husband or Nelson her lover?). For those who knew the story of Messalina, her image (like that of Vitellius in Couture’s Decadence) offers reassurance that the licentious disorder she represents will come to an end. And that is what we witness, in a scene depicted with brutal clarity by an artist who made ancient celebrity deaths something of a speciality: she was shortly finished off by her husband’s henchmen, in his pleasure gardens—as one ancient writer put it, like a piece of ‘garden rubbish’ (Fig. 7.11).34

7.9 Aubrey Beardsley’s drawing of 1895 of Messalina and her companion (or servant or slave) on a night out. Less than thirty centimetres tall, the image fades the companion into the night while drawing all attention to the skirt—and breasts—of the empress.

7.10 In James Gillray’s cartoon of 1801 pillorying Emma Hamilton (the lover of Lord Nelson), she is pictured watching Nelson’s fleet depart. The head of Messalina from her husband’s collection of antiquities is on the floor, between a phallus and a Venus. The title adds to the (uncomfortable) joke: ‘Dido, in Despair!’ evokes the story of the queen of Carthage who, in the founding myth of Rome, killed herself when she was abandoned by the ‘hero’ Aeneas, who sailed away to his destiny.

‘For those who knew the story’ is of course crucial. Some of the tales lying behind these images may now be as unrecognised by most of us as the more arcane byways of the Old Testament (and they may never have been part of people’s ordinary everyday repertoire). But it takes only a little decoding to see how artists were using, and cleverly adapting, them to offer sharp reflections on the role of women in the hierarchy of power—and to open a window onto the corruption at the domestic heart of the empire. Carefully comparing different versions reveals how tiny changes of context, focus or personnel prompt significantly different reflections.

7.11 Georges Antoine Rochegrosse flaunts the Death of Messalina on this large canvas (almost two metres across) painted in 1916. Messalina herself, in the scarlet dress, is grabbed by a soldier, while on the left her mother (who had tried to persuade her daughter honourably to take her own life) cannot bear to look.

One of the most surprisingly influential stories in the repertoire brings the Roman poet Virgil face to face with Augustus and the emperor’s sister, Octavia. Taken from a rather uninspired biography of the poet, written in the fourth century CE long after his death, and on who-knows-what factual basis, it tells how Virgil went to the palace to read out selections from his epic poem the Aeneid, to give the emperor a sneak preview. But the recitation was suddenly interrupted. When he came to the part of his poem that mentioned Octavia’s son Marcellus, who had recently died, the mother was so overcome that she fainted and could hardly be revived35. It was an extremely popular theme for painters in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, partly because it hinged on the power of creative art to overwhelm its audience: the challenge was to capture in painting the impact of poetry. That is exactly what Angelica Kauffman (one of the few female artists I am able to put in the spotlight) shows in a nicely down-to-earth version of the incident painted in 1788, Virgil Reading the ‘Aeneid’ to Augustus and Octavia (Fig. 7.12). Here Octavia has passed out, Virgil is looking understandably unnerved at the effect he has had, Augustus seems shocked but uncertain what to do, while two capable woman servants—one of whom is shooting an accusing ‘look what you’ve done’ glance at the poet—take care of the casualty.36

7.12 In Angelica Kauffman’s painting of Virgil Reading the ‘Aeneid’ to Augustus and Octavia (1788), the women are the stars of the occasion. They are highlighted at the centre of the canvas (a metre and a half across); the two servants take Octavia (who has collapsed in distress at the mention of her dead son) in hand; the emperor and the poet are pushed aside.

Other artists, however, gave this a far more sinister spin—notably Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who over more than fifty years produced at least a hundred drawings of this scene, as well as three paintings. But he included an important addition to the cast of characters.37 For Roman rumour alleged that Livia had been implicated in Marcellus’s death, fearing the young man was a rival to her own son Tiberius in the competition to be made Augustus’s heir. In each of his paintings, starting in the early 1810s (Fig. 7.13), instead of Kauffman’s sensible servants, Ingres has introduced the elegant, mature and alarmingly steely figure of Livia, who is not mentioned in the ancient account of the incident. Her attitude betrays her guilt. She gestures only perfunctorily to Octavia’s plight, and in two of the versions she turns her gaze away into the distance, as if she had no emotional engagement with the events at all, or at least had more important things on her mind. In the final painting, completed in 1864 by colouring an earlier engraving, the group is dominated by a statue of Marcellus himself, and two elderly courtiers (also present in an earlier version) mutter to each other in a corner in a knowing huddle, while on the other side, half cut off by the edge of the canvas, a servant lifts up her hands in horror—as any innocent viewer, who read the scene correctly, might have done.

Ingres here cleverly plays off different versions of the stereotypes of imperial women: the innocent victim versus the deadly power behind the throne. But he does more than that. He points to a different version of the corruption of autocracy, which goes far beyond, or much deeper than, the crude debauchery of Couture’s Decadence. In Ingres’s re-creation of what at first glance might seem like an ordinary domestic scene (not far from ‘Victorians in togas’), there is a profoundly uncomfortable version of vice. This is a Roman imperial court in which the normal rules of humanity no longer apply: one in which the murderer coldly cradles the widow of her victim, and only the servant girl seems upset.

The Agrippinas

It is, however, in the visual re-creation of the Agrippinas, mother and daughter, that we find the most compelling and disturbing reflections on the Roman court and the imperial family. They were key figures in the transmission of imperial power, from the beginning of the first dynasty to its end. Agrippina the Elder, the natural granddaughter of Augustus by his second wife Scribonia, was the only one of his grandchildren not to be either dead or in exile when Augustus himself died in 14 CE. The Younger, her daughter, was the last wife of the emperor Claudius and the mother of the last Julio-Claudian emperor, Nero. As Madame Mère found to her cost, they have been perilously easy for modern viewers (and ancient viewers too, I would guess) to confuse. One Agrippina can seem much like another, the long-suffering widow of Germanicus always in danger of being mistaken for her scheming and murderous daughter.38

7.13 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres returned to the scene of Virgil reading his poem to the imperial family many times from the early nineteenth century to 1864, in different formats and at different scales; but the presence of Livia, who was said to have played a part in the death of Octavia’s son Marcellus, adds a sinister twist. Of these three: (a) the largest version, c. 1812, about three metres by three, in which Augustus cradles his sister, while Livia looks on; (b) a later version from 1819, cut down to about a metre and a half square from a larger painting, to focus only on the three protagonists; (c) a much smaller version (roughly sixty by fifty centimetres), painted in 1864 over an earlier engraving, which brings a statue of Marcellus himself into the centre—while the servant on the far left starts back in response to the scene.

Alma-Tadema was only one of many artists to immortalise the Elder. Since the eighteenth century, their prime theme has been her loyal journey home from Syria with her husband’s ashes. This meant statues of her, veiled, carrying the urn, dotted around the parks and galleries of Europe (though, as was recognised already in the eighteenth century, there was a tendency to see an Agrippina in every statue of a Roman woman39); and it meant narrative paintings with all kinds of different nuances. Benjamin West, for example, in the 1760s, just a few years before his Death of Wolfe, focussed on her landing in Italy—making it a highly ritualised, heroic moment, almost literally spotlighting the noble heroine holding the urn to her breast as if it were her child (Fig. 7.14).40 Half a century later, J.M.W. Turner re-created the same scene, but he made Agrippina and her children a diminutive group scarcely visible on the bank of the Tiber, completely overshadowed by the vast monuments of ancient Rome. This was originally designed as one of a pair with a painting of the modern ruins of the city—more than hinting that the tragedy of Agrippina was the beginning of Rome’s fall.41

7.14 Benjamin West’s monumental depiction (two and a half metres wide) of Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus (1768). Agrippina with the remains of her husband, and with her children and attendants, has just arrived at the port of Brundisium in Italy. Pale but brightly lit, this group is the centre of attention, and people have flocked to see, admire and grieve with them.

7.15 This late fifteenth-century woodcut from a German printed edition of Boccaccio’s On Famous Women depicts in medieval guise the punishment and torture of Agrippina. The emperor Tiberius directs proceedings on the right; the terrified Agrippina on the left is force-fed by two of his henchmen.

Other parts of her story have been captured too. In the seventeenth century, she was depicted by Nicholas Poussin grieving by the deathbed of Germanicus, with young Caligula, a threat as much as a hope for the future, by her side42—a subject later set for the young French artists competing in 1762 for the sculptural branch of the Prix de Rome to render into marble.43 There are even a series of uncomfortably matter-of-fact medieval images (not so far from the ‘humour’ of those seventeeth-century Romans who composed the inscription on the pedestal for her tombstone), which show the unfortunate woman in exile, being force-fed by Tiberius’s apparatchiks to prevent her martyrdom, all in contemporary medieval guise (Fig. 7.15).

But in general, whatever accusations of stubbornness there might have been against her, over the last three hundred years or so Agrippina the Elder has proved to be an easy fit with a variety of political positions. For moralists, or anti-monarchical radicals, who often valued wifely loyalty as much as they detested tyranny, she was the perfect combination. She had her uses among royalty too, however. West’s painting of Agrippina landing at Brundisium established his reputation in England. This was partly because it could be conveniently exploited in favour of George III’s widowed mother Augusta, who—almost foreshadowing the later dilemmas of Madame Mère—had been satirised as an Agrippina the Younger for her supposed controlling influence over her son.44 West’s painting played its part in retuning the image of the Dowager Augusta as the fiercely loyal widow, Agrippina the Elder.

For one of the problems with the younger Agrippina in the standard Roman historical narrative (accurate or not) was precisely that she was supposed to have wielded far too much power over her son Nero. It was not simply that, after her marriage to Claudius, she managed to fast-track him to the throne in 54 CE, aged sixteen, by-passing the unfortunate Britannicus, Claudius’s natural son by Messalina. The story was that at the beginning of Nero’s reign, she really was a major political force in the palace, underpinned by the incestuous relationship into which she had enticed the boy (pictured rather decorously in Fig. 7.16, in an otherwise raunchy eighteenth-century collection of the sexual exploits of the Twelve Caesars turned into soft porn). But it was not long before her son had had enough of her, and by the late 50s—so the story went—he had decided that the only way to free himself from Agrippina was by murder. The villain then turned victim.

7.16 One of the most notorious books of erotica of the late eighteenth century was by the ‘Baron d’Hancarville’ (as he liked to call himself), which focussed on the sex lives of the Twelve Caesars, and more especially their wives: Monumens de la vie privée des XII Césars (almost Evidence for the Private Life of the Twelve Caesars). In comparison with the others, this scene of Nero and Agrippina is rather delicately chaste.

Nero’s first attempt was an almost comical failure. He had a collapsible boat built, which self-destructed as planned when Agrippina was out to sea—but the plot was foiled, because it turned out that his mother could swim. So he fell back on more conventional means and sent in a hit squad. Roman writers dwelt on some of the most lurid, personal and very likely fantastical details of the killing. One claims that, in her last words, Agrippina told her assassins to strike her womb. Suetonius tells how Nero (a drink in hand) inspected his mother’s naked body after her death, praising some parts of it, criticising others.45

7.17 In this painting of 1878, more than one and a half metres across, John William Waterhouse focusses on The Remorse of Nero after the Murder of His Mother. The image of the young emperor is uncannily close to that of a moody modern teenager.

Modern images of Agrippina the Younger have been dominated by the story of her murder, from the moment when Nero takes a quick break during a grand dinner to order her assassination, to John William Waterhouse’s reflection on the aftermath of the crime (an attempt to penetrate the psychopathology of the young sadist, which picks up Suetonius’s claims that the emperor was plagued by guilt at what he had done) (Fig. 7.17).46 But it is the relationship of the emperor to his mother’s naked corpse that was the most popular subject. A series of unsettling voyeuristic images from the end of the seventeenth century on re-enact Nero’s inspection of the body: sometimes a clinical appraisal of her remains appears to be taking place; sometimes the emperor can barely bring himself to look at what he has done; sometimes he gets uncomfortably close to the woman who had been both his mother and lover. Whether it is the leopard skin rug on which the dead Agrippina sprawls in one painting or the almost pin-up breasts and languid poses of many, it is impossible to ignore the eroticism that combines with the violence here (Fig. 7.18).

But the ‘appeal’ of Agrippina’s body goes back to the Middle Ages, centuries earlier, when repeated images in manuscript illuminations and in woodcuts portray Nero not simply inspecting the body, but supervising (or in at least one case actually carrying out) its dissection. In a variety of gruesome scenes—the coloured ones are the worst—the woman’s abdomen is being slit open, to reveal the organs within. It is not always clear that the victim is dead, raising the question of whether this is an autopsy or vivisection (Fig. 7.19).

7.18 Arturo Montero y Calvo’s huge canvas of 1887, five metres across, displays Nero before the Corpse of His Mother. The emperor on the left gazes on the semi-naked body of Agrippina, while holding her hand. His advisers on the right scrutinise her with (for us) uncomfortable curiosity.

Although a number of elements in these pictures may go back to ancient accounts of the aftermath of the murder (Suetonius’s glass of wine, for example, appears in some images), the dissection and its details are not a Roman story. All these images are illustrations of a hugely popular medieval elaboration, which told how Nero had his mother cut open so that he could find her womb. It is found in, among other places, the thirteenth-century Roman de la Rose, the ‘Monk’s Tale’ in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales a century or so later (‘he hir wombe slitte, to biholde / Wher he conceived was’), and in that early fifteenth-century mystery play and box-office hit, Le mistère de la vengeance de la mort et passion Jesuchrist, in short, the Revenge of Jesus Christ). Popular in various manuscript and printed versions, in different European languages, this dramatised the punishment of the Jews for the crucifixion of Jesus culminating in the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by Vespasian and Titus, but with various subsidiary narratives leading up to it. The dissection of Agrippina is one of those. Whether this was actually performed on stage, or merely narrated, is not entirely certain. But one French printed version implies a performance, and gives the stage directions. Agrippina appears to be still alive, so she is ‘to be tied to a bench, her belly facing up’. Thankfully, it goes on to say that ‘a prop (fainte) is needed in order to open her up’. It was to be a clever piece of theatricals, not live surgery.47

7.19 A tiny image in a late fifteenth-century manuscript of the Roman de la Rose shows Nero clothed in red medieval dress watching the dissection of his mother (her ankles tied together) and the exposure of her womb: almost a scene of butchery.

This story has sometimes been seen as a flagrant case of the medieval enthusiasm for violence and extreme spectacle, the writers, artists and theatrical managers of the time taking the opportunity to add extra blood and guts to what was already a bloody incident. And the later images have also been related to contemporary debates about scientific dissection (how transgressive or justifiable was it? How was it to be represented?). But even more significant is the connection of the story with the issues of women’s role in imperial succession and the transmission of power. For the nub of it does preserve a connection with the ancient account that explained how Agrippina exposed her belly and asked her murderers to strike her womb. As Chaucer underlined (and it is a detail repeated in the other versions), Nero wants to find his mother’s organs of reproduction. That hints, of course, at the incestuous relationship between the two. But more than that, the story displays, makes explicit and ‘dissects’, both literally and metaphorically, the woman’s role in making and conceiving emperors.

That interpretation is supported by what happens next in some versions of the story, including the thirteenth-century collection of saints’ ‘Lives’ known as the Golden Legend. Here, in the ‘Life of Saint Peter’, Nero insists that the doctors who have been dissecting his mother make him pregnant. As they know that this is impossible, they give him a potion in which a tiny frog is concealed, which grows in Nero’s stomach, eventually causing him such pain that he has to give birth to it by vomiting—though he is then desolated to find that all he has produced is a messy, bloody frog. The doctors blame him (he had not, after all, gone the full nine months), while the frog is kept safe but locked away, until at the fall of the emperor the poor creature is burned alive.48

Where this story came from is unknown. It may, or may not, be indirectly related to one ancient account of Nero taking the theatrical role of a woman in childbirth, and to another ancient story that he would be reincarnated as a frog.49 Its message, however, is clear: not only are men incapable of producing children without women, but emperors on their own are incapable of transmitting the power they wield. What looks like a lurid medieval fantasy, with its dissection, phantom pregnancies and frogs, in the cruel aftermath of matricide, in fact points directly at the big issues surrounding the role of women in the Roman imperial and dynastic succession; it re-presents in a surprising form some of the key debates and anxieties embedded in the images of ‘empresses’ ancient and modern.

Agrippina the Third

Those medieval images of Agrippina sliced open could hardly be more different in style from an elegant and much-admired painting by Rubens that now hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, painted in the early seventeenth century, only a hundred years or so after those last dissections. Taking us back to Agrippina the Elder, who launched this chapter, this double portrait is now entitled Germanicus and Agrippina. It depicts the determined and devoted young couple, side by side, in profile—Agrippina in the front plane, partly concealing her husband. Another version of the same characters, by the same artist, is in the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, but here, though the arrangement is basically the same, it is reversed, with the man in front of the woman (Fig. 7.20). Art historians have argued about the relative quality of the two pieces (some preferring the Washington version, some the Chapel Hill), about the reasons for the different prominence of the man and the woman and about the micro-history of the panels (one suggestion is, on the basis of the construction of the wood backing, that ‘Germanicus’ was an afterthought in the Washington painting, originally intended as a portrait of ‘Agrippina’ alone). Yet, however those issues are resolved, there are even more intriguing questions of identity that have a major impact on our interpretation of the scene, and introduce another unexpected layer into the ‘Agrippinas problem’.50

7.20 Two early seventeenth-century versions of a double imperial portrait by Rubens (both over half a metre tall), now usually identified as Germanicus and his wife Agrippina the Elder: (a) the version now in the National Gallery in Washington, DC; (b) a similar version, though reversing the figures, now in the Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. But the earlier identification of these figures as the emperor Tiberius and his first wife, another Agrippina, was not necessarily wrong.

This double-profile form is a classic example of Rubens’s use of antique models; for ancient gems and coins, which the artist is known to have studied closely, regularly arranged heads in this way. One particular source of his inspiration, though clearly not the exact model, is often assumed to be the so-called ‘Gonzaga Cameo’ (Fig. 7.21), an ancient gem much admired by Rubens when he was working in Mantua between 1600 and 1608, and variously identified over its modern history, as depicting Augustus and Livia, Alexander the Great and his mother Olympias, Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, Nero and Agrippina the Younger, Ptolemy II of Egypt and his wife Arsinoe and almost any other famous ancient couple you could think of.51 There have even been some ambitious, though ultimately inconclusive, attempts to pin down particular features of Rubens’s ‘Germanicus’ to portraits then identified as the prince on ancient coins and gems that the artist knew, or might have known.52 But, although the overall design of these paintings clearly does reflect a characteristic ancient form, it is far from clear that Rubens intended his characters to be Germanicus and Agrippina.

7.21 The so-called ‘Gonzaga Cameo’, almost sixteen centimetres tall, may date back to the third century BCE (but that depends on who you think the figures represented are, and it could be from several centuries later). Its layout, with two adjacent profiles, found in other ancient cameos, lies behind Rubens’s design in Fig. 7.20.

In a way reminiscent of the shifting identities of so many Roman portraits themselves, different names have been applied over their history to the couples in each of these paintings. According to a 1791 sale catalogue compiled in Paris, the Ackland version was then believed to be a portrait of the eighth-century Byzantine emperor Constantine VI, and his mother and co-regent Irene; for most of its time in Chapel Hill, since 1959, it has been rather guardedly entitled Roman Imperial Couple.53 The Washington version was bought in the early 1960s from a collection in Vienna where it had been since 1710, known as Tiberius and Agrippina.54 But in Washington doubts were raised almost immediately, and by the end of the 1990s it had been officially renamed Germanicus and Agrippina; recently the Ackland Museum has followed suit, and their Roman Imperial Couple is also now Germanicus and Agrippina. Why?

TABLE 3

Apart from the usually treacherous attempts to match up the physiognomy of the male figure to other so-called Germanicuses (the ‘Agrippina’ has never been a major part of this game), one powerful impetus behind the change of identity is that, if you know a little of their story, Tiberius and Agrippina sounds such an unlikely pairing. Why, we cannot help but think, would Rubens have put the implacable Agrippina in a pair with her bitterest enemy Tiberius, who either killed her or forced her to suicide? It makes no sense at all.

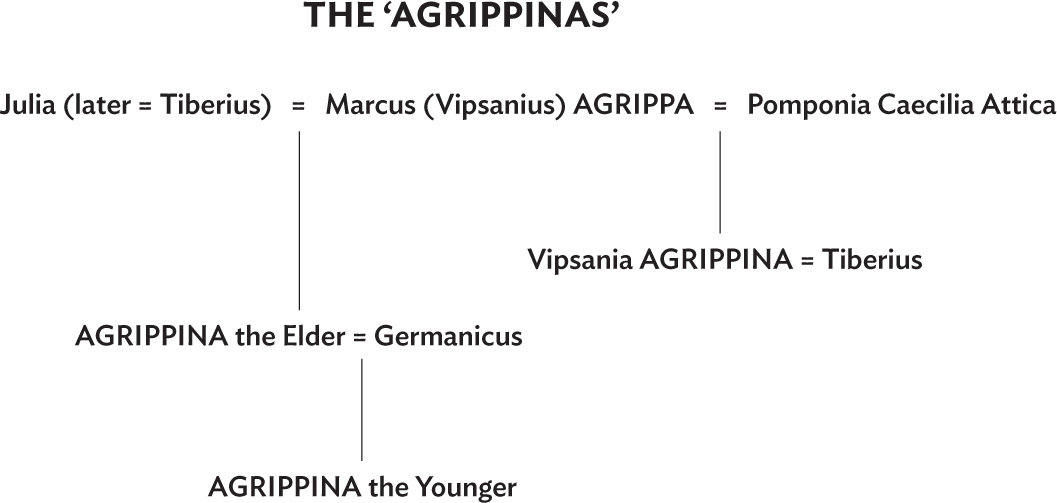

At this point, I have to introduce a new character. For there were not just two Agrippinas, but three. As the family tree shows (Table 3), Agrippina the Elder was the daughter of Augustus’s daughter Julia and her second husband Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, her full name being Vipsania Agrippina. But Agrippa had been married before, and there was a daughter of that marriage, who was also known as Vipsania Agrippina. We now call this Vipsania Agrippina just ‘Vipsania’, but that is largely to avoid the confusion of having too many Agrippinas around. In antiquity, and right up until at least the eighteenth century, she was usually referred to, like the others, as Agrippina. There were always three of them.

This third Agrippina was the first wife of the future emperor Tiberius. She is pictured as that (under the name ‘Agrippina’) in Sadeler’s line-up of empresses (Fig. 7.7c). The catalogue of the Vienna collection refers to her explicitly as the wife of Tiberius—and the expert curators in Washington, DC who ushered in the new identification were well aware that Tiberius had been married to an ‘Agrippina’. But, in the modern view of Roman history, it has always been hard to see them as a plausible imperial pairing (not to mention the unexpectedly idealising representation of ‘Tiberius’ in these paintings).55 That apparent incongruity meant that the emperor and his first wife, Vipsania Agrippina, were simply cast aside, and a new identity found. We are never likely to know for certain what Rubens had in mind, but there is no strong reason to suppose that the traditional title is wrong, and some reasons to think it was right.

For it does offer a particularly rich reading of the painting. Tiberius may have had a generally bad reputation in ancient and modern literature (if only as a morose hypocrite, who was Augustus’s last choice as heir, despite being Livia’s natural son), but according to Suetonius there was one woman to whom he was devoted, in true love. That was Vipsania Agrippina. But he was forced by his stepfather Augustus to divorce her, so that he could marry, for entirely dynastic reasons, Julia, Augustus’s own daughter (it only added to the marital intricacies that Julia had been the wife of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the father of Vipsania Agrippina). Tiberius was utterly opposed to the idea (and in the standard story, with its predictable dash of misogyny, Julia turned out to be a bundle of trouble), but he had no choice in the matter—and he never got over it. According to Suetonius, after this divorce, when Tiberius was still almost in mourning for Vipsania Agrippina, on one occasion he spotted her in the Roman street, and he followed her weeping. His minders ever after took great care that he should never catch a glimpse of her again.56

Maybe we have a hint of that in this image of two people staring in parallel, not looking at each other but held in the same canvas. Indeed, it is hard to think of a better way of capturing the relationship between Tiberius and his Agrippina. Rubens has, in other words, breathed life into what was almost a visual cliché of ancient cameo design, by blowing these figures up to almost life size and giving a new story, and a new significance, to the visual form.

We have learned again what a difference a name can make—even if in this case it is the same name.