CHAPTER ONE

Understanding the Effects of Overload

There’s more information around us than ever before. E-mail, 24-hour news and social media are an almost constant source of distraction. We know more about our world than any previous generation. We also measure everything. We measure our weight, steps, heart rate, the time we take for activities, our sleep, our calorie intake – and that’s just the personal information. In the workplace, the compulsion to measure and analyse is even greater. But what if all this information that we rely upon so much for our logical, analytical approach had become so abundant that it was inundating us and our understanding?

In this chapter, we look at how the volume and type of information are changing leadership culture. We’ll see how it is undermining our ability to make sense of the world by constantly interrupting and changing our thought processes. We’ll also see how our own filtering and that of others can narrow our field of vision. We’ll look at the technological changes of the past decade and show how, in many instances, they have created paradoxical effects. This is creating polarities that demand a new type of thinking away from just analysis towards parenthesis. Analysis focuses leadership goals on the short-term, quantitative (often financial), tangible goals. It marginalizes those of little economic value and ignores wider community goals such as caring and compassion. Leaders need more balance between the two kinds of thinking and more fluidity to shift between them.

In this chapter, this is what we will cover:

- Left-brain process

- Right-brain process

- The overload

- How it changes us

- The algorithms make this worse

- News is about profits, too

- Is the overload hurting our creativity?

- The sort of people we’re becoming

- The siren call of the numbers

- Analysis versus parenthesis

- Our socio-economic perspective also dictates our understanding

- A mixed reality environment

- How this changes the leader’s mandate

- Spotting the signs of a waterboarded leader

- Conclusions

Before we explore this further, we must review how we process information using the two main techniques that we have at our disposal.

Left-brain process

These are the logical, rational processes at the core of Western Reductionism. Although it has its roots in antiquity, in the work of Aristotle and Plato, its modern application really dates from the age of Enlightenment. This was an intellectual and philosophical movement of the 18th century that saw the flourishing of science and the pushing back of theology in Europe.

At its core, reductionism or the left-brain process allows us to compare, contrast, analyse and measure. It provides us with our convergent or analytic capability. By its nature, this process separates and atomizes because it focuses attention on that which is different. Computers are excellent assistants when it comes to processing and breaking down data because they are founded on logic. They allow us to calculate answers and build complex models which can be run and re-run to test hypotheses and assumptions.

Analysis allows us to reach the correct answer with certainty. It allows us to develop scientific thinking and has been the single most productive philosophy mankind has embraced. This is why it has been adopted by all of the most industrially advanced nations, in schools, universities, government, the military and commerce. The most skilled intellects (as defined by their ability to use logic and rational thinking) are the most highly prized and sought after in all walks of life.

When first meeting someone or when we’re interrupted, alerted or distracted, it is to the left-brain process that we turn. The process helps us assess a situation, tells us what the information is, what we need to do with it and how and when to respond. This analytic, logical and reductionist ability is so powerful and all-encompassing as to almost completely eclipse the other major process which we know is there, but is harder to spot.

Right-brain process

These processes don’t just deal with the opposite of reductionism, they also deal with synthesizing, contextualization and broader vision. These are termed divergent processes, because they seek to join things up rather than separate them. They are slower and rely heavily on what we might call offline processing. How do we know this? Well, it’s difficult to prove scientifically. In Too Fast to Think1 a survey of leaders from many different backgrounds was undertaken. All the leaders were experts in the Western Reductionist tradition. They all had one degree, some even had two, with further professional qualifications on top of that. They were asked where they were when got their epiphanies or best ideas.

The results were fascinating. More often than not, they reported their best ideas came when they were away from their workplace, not doing something work related and, most importantly, not trying. These leaders all reported their greatest ideas when they were in the shower, the gym, driving, walking the dog, about to fall asleep, listening to music, in conversation, sitting on a train or plane, in fact almost everywhere except the office. Can this be mere coincidence?

It was Einstein who said: ‘Creativity is the residue of time wasted.’ The implication here is quite clear. When we’re doing nothing, we’re really doing quite a bit. Einstein also added: ‘If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.’2 It’s unlikely he would have made much progress on his problem had he been constantly interrupted by e-mail and social media notifications.

This points to the power of the right-brain process, which is slower and constantly churning whether we’re aware of it or not. It comes forward when the left-brain process recedes for whatever reason. By its very nature, it is difficult to prove logically, but we know it’s happening because so many report it. We don’t just use this process for painting or writing; our right-brain creative ability is an important part of how we solve problems and reach potential. Right-brain process accounts for beliefs such as faith, trust and hope, which are all as important as logic, if not as ostensibly credible.

The overload

We see our world from under an ocean of information and interruption. The scale of the information overload and disruption is enormous. If we just take e-mail, for instance, according to Radicati Group the average business user sent and received 121 e-mails a day in 2014, and this is expected to grow to 140 e-mails a day by 2018.3 If we assume a 10-hour day at work, even at today’s levels, that’s twelve an hour or one every six minutes, often with an alert attached to it.

The number of worldwide e-mail accounts is expected to grow from over 4.1 billion in 2014 to over 5.2 billion by the end of 2018. The total number of worldwide e-mail users, including both business and consumer users, will increase from over 2.5 billion in 2014 to over 2.8 billion in 2018.4

So, on average, we check our e-mails at least 20 times a day.5 In a normal working day, that’s an interruption at least every 20 minutes. Once you add social media notifications from Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram and so on, we’re being interrupted every few minutes. This makes us the most distracted audience ever. We’ve stopped paying attention to anything other than basic headlines and what’s front and centre. One survey showed that millennials were checking their phone 150 times a day.6

QUICK TIP Leaders should use aggregators like Hootsuite to ensure they can see all social media in one place. This also allows multiple channels, eg Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, to be updated simultaneously.

It’s hard enough just to keep up with the information we’re being given. Worse still, the information is in many formats and locations, so we can’t escape it. People send us messages on so many different platforms that we can’t remember where to find it – WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, LinkedIn, WeChat, Instagram messaging – the list goes on. The current affairs news media are the same – too many channels with too much stuff. Social media have become like drinking from a fire hose.

Users of the top messaging apps have now accelerated past those on the social networks. Monthly active users on the big four messaging apps, WhatsApp, Messenger, WeChat and Viber, outnumber those on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.7 People already use these channels to interact with each other and expect brands to do the same. Brands are now struggling to answer all those messages because of the sheer volume. Sixty-six per cent of consumers prefer to interact with brands through messaging apps.8 This is where so-called chatbots can add value to close that gap (more on this in Chapter 6).

How it changes us

In responding to overload, our behaviour changes in many ways. Some people are overwhelmed by the relentlessness of it and opt out. Some create windows of time when they can deal with it. Most of us just start to filter:

- We filter in news about the family. We now know more than ever about what our cousin is doing than we did before. People we only ever heard about previously once every few years are now updating in real-time.

- We filter in news about friends. Now we don’t wait for a postcard or until they return from holiday, we get the detail in real-time.

- We filter in stories about violence. We hear about shootings, murders, sexual violence, thefts and muggings. We hear about events that people think were acts of terrorism but turn out not to be. We hear about terror unfolding in real-time. We even hear victims’ last words.

QUICK TIP Leaders need to actively pull in good stories and avoid being sucked in to negative stories and thinking. They need to remind their teams that the world is not always as terrifying as it’s reported to be.

- We filter in news from sources that agree with us. This has always been the case. Most consumers of media have always subscribed to channels that support and reflect their views.

- We filter in stories about celebrities. According to London’s Daily Mail it is now the largest online site in the world having overtaken The New York Times.9 This is largely down to its coverage of celebrity gossip.

- We filter in stories about cats that look like Hitler (‘Kitlers’, if you’re wondering).

Our information is also layered as if to create multiple realities. Take a tennis match for instance. We can see it first hand in immediacy. We can see it shortly after on social media. We can then view it on TV a little bit later. Then we can read about it in the press even later and maybe in history books long after the match.

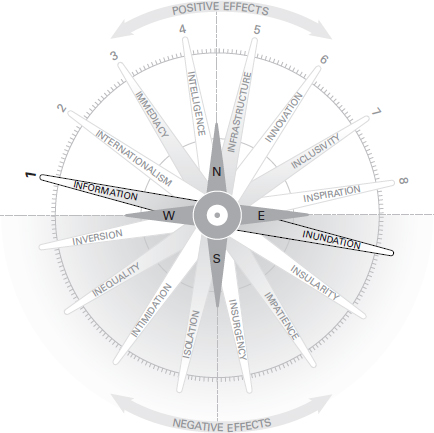

For business performance, it’s very similar. We can produce a set of business results, then wait for social media, read the minutes, see mainstream media, with accountants and then lawyers commenting. At every stage, we understand more about the truth, but frequently we don’t have time for anything other than the headlines. This is because everyone can see everything as it happens all the time, in real-time. At each stage, though, different detail is released. This is because speed is inverse to truth (Figure 1.1).