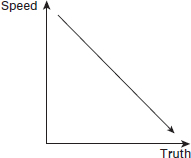

Figure 1.1 Speed against truth

Source: LEWIS Rise Academy

So, we can see an event that contains all the same basic facts but reported in very different ways. This gives us multiple versions of reality, depending on where the process is joined. We give priority to the first version of the truth we heard.

The algorithms make this worse

To make the provision of news more efficient, internet algorithms recognize what news we have consumed, then we’re automatically served more information about what we already have shown interest in. We end up unconsciously drilling down into a subject area because an algorithm has decided that’s what we want. Algorithms focus our vision on what we’ve already consumed. This denies us the capacity to look across the landscape. That means we are often protected from information that for whatever reason we don’t normally hear. It’s difficult to be tolerant of other opinions if you never hear them. Social media similarly create an echo chamber or a silo where the capacity to drill down is not matched by the ability to look across. Not only do we not hear about other opinions, but we don’t care or we discount them.

The constant interruptions also have another effect. They make us stressed. We feel constantly short of time. We are unable to complete tasks. We lose the thread of our thoughts. Every time we try to concentrate we get interrupted, which further undermines our ability to cope. It undermines our confidence in decision-making because there is always someone who is better informed.

News is about profits, too

Why do we want the news anyway? Is it because we want important facts? Well, without doubt transport, weather and local news can be helpful. Being informed in general can be useful to our careers. News providers know, however, that they can gain more attention if the news is entertaining. But let’s be clear: the purpose of news media is not to inform. It is to make a profit. That too influences what we get to see and how we see it.

Scandal, sensationalism and threat to the community have long provided a source of stories. A good story is never just a true story, it’s an entertaining one. Never let the facts get in the way of a good story. Why does this matter to leaders? Because leaders will always have stories told about them. Leaders should decide who tells that story and what it should be. If they don’t, then the story could be very different. What is beyond doubt, though, is that there will be one.

Of course, people want entertainment but they also want validation. They want to agree with opinions they hear. That’s why traditional outlets have been split along political, regional or gender lines. Now information is so intricate that, in theory, we need never listen to disagreeable or boring information again. We consume according to our tastes, but then wonder why the world makes no sense.

The implications of the above for all types of leadership are profound. Messages that are subtle, slow, dull, complex and sensitive are filtered out. So, if you’re in any type of leadership role, it’s difficult to get people’s attention unless you speak with passion, emotion and you use the primary colours.

Is the overload hurting our creativity?

In short, yes. The interruptions are having obvious effects on us. What about the not so obvious effects? Short-term distractions are without doubt a hindrance to our long-term, sustained creative thinking. The brain has inherent deep processing capability which continues even when we are unaware of it. Only when we stop do these thoughts have the chance to surface and come to the attention of the conscious mind. It is our innate ability to solve problems that dictates how much of our potential we’re able to attain.

It’s not that the smartphone isn’t a great utility for mankind. It makes us more connected, more productive and more aware.However, there is a cost of accessing these benefits. Despite its simplicity, the most difficult feature to use on the smartphone remains the off switch.

The sort of people we’re becoming

The filtering we talked about above is just like a sedimentary process: it gradually builds, layer upon layer, into a view of the world. We have become more:

- Frightened

- Angry

- Distracted

- Bored

- Intolerant

- Impatient

- Cynical

- Opinionated

- Informed (but not always helpfully).

Being constantly fed with news and information also creates a false sense of security that we know what’s happening. The problem is that we think we’re choosing the information we want without realizing that, in so many instances, it’s already been chosen for us.

To some extent, this is happening to all of us and narrowing our field of vision. Over this must be overlaid an increasing tendency to analyse.

In this increasingly complex and specialist world, we have experts everywhere. We have more graduates than ever before. People who like to analyse things. Analysis has become our default method of examining the world. As explored in Too Fast to Think, analysis is part of the left-brain process. It loves to compare, contrast and analyse. Most criticism comes from this source. Of course, we also have another – the right-brain process – which takes us in an opposite direction towards trust, purpose and belief. These are the irrational, but nonetheless vital, elements.

The siren call of the numbers

It is nigh on impossible to gain entry into the world of leadership unless one is comfortable conversing in numbers. Maths, models and algorithms are the language of a financial priesthood that values and measures everything numerically. Spreadsheets and balance sheets are the foundations of this religion.

As a result, boards the world over spend ever more time and money sharpening these analytical tools so that they can crunch more numbers and process data at an ever-faster pace. Fiduciaries have been seduced by the deeply alluring promise that technology will help them perform better. Anyone who suggests that the answer might not lie in the numbers risks being excommunicated, even though they know financial accounts are only as good as the numbers they are given. This applies across all industries and leadership teams. The phrase is that decision-making must be ‘data driven’, as if somehow qualitative data were inadmissible or that numbers were not nuanced.

Numeric skills alone do not automatically equate to better performance – witness what investors missed in the past decade alone despite their mathematical tools: the 2007 financial crisis, the Arab Spring, the US economic recovery, Brexit and the migrant crisis.

Why did they miss all this? It seems that the most important forces in the world economy today are not the ones that can be quantified or predicted. Leaders shy away from these areas for the very reason that they involve subjective data. If they need to enter these areas, they like to equate polls with facts. They like to believe that human inclinations can be systematically measured and valued. The real drivers in these areas have to do with the level of anger in society, the loss of community and the destruction of hope. The perception that wealth and power are distributed unfairly and the collective failure of leadership are some of the most powerful forces that leaders face.

How else do we explain the anger that has resulted in the anti-establishment movement which gave rise to nationalist movements such as the 2016 US presidential election result and Brexit? How do we put a number on the sense of loss that drives immigrants everywhere to endure deep physical and emotional trauma in their search for a better life somewhere else? How do we assign a number or measure the anti-immigration mentality that is gaining ground everywhere today?

Consider what the father of public opinion polls had to say about all this. Daniel Yankelovich founded the original New York Times/CBS poll. He said:

The first step is to measure what can be easily measured. This is okay as far as it goes. The second step is to disregard that which cannot be measured, or give it an arbitrary quantitative value. This is artificial and misleading. The third step is to presume that what cannot be measured is not very important. This is blindness. The fourth step is to say that what cannot be measured does not exist. This is suicide.

Perhaps leadership should spend more of its time looking at new methods to measure that which cannot be measured?

QUICK TIP Leaders should seek to assess data by value as well as volume. For instance, knowledge of a competitor’s move may mean more than spotting a trend in their own organization.

So, perhaps we need to add something new to the existing armoury of tools – things that precede movements in data, including stories, anecdotes, narratives and early signals. We need to suss the Zeitgeist/situational fluency and capture the mood before the data catch up. Leaders will recoil in horror at this suggestion. After all, these are all unreliable because they are subject to human judgement. They cannot be scientifically proved. They are not systematically observable because human opinions vary so much. But perhaps the industry will indulge in this notion given that performance has been so poor for so long.

The great problem with analysis is that, by its very nature, it focuses on historical data and logic. This means it concentrates on the past. It might provide insight for management, but it won’t help leadership.

Let’s take a simple example. If we analyse a car, we can conclude it is made up of systems such as steering, transmission, an engine and instrumentation. They work together to create a beneficial transportation device for humans. If we use parenthesis, we look at how the car’s systems interact with other systems. For instance, it takes unsustainable fossil fuels and turns them into carbon dioxide. It takes well human beings and injures them. It takes quiet countryside and turns it into noisy congestion. If we apply two similar intellectual processes, we arrive at two paradoxical conclusions. At once, the car is both a help and a hindrance.

QUICK TIP Leaders should use the telescope as well as the microscope. By all means analyse, but remember to parenthesize

Leaders may be inclined to fall back on number-based tools but they are, by definition, backward-looking – they rely on historic information. Data, maths, models and even algorithms are all backward-looking. They rely on events and information accumulated in the past. We like to think we can extrapolate this into the future. This seems especially odd and even ironic given that everyone in the fiduciary world knows that past returns are no guarantee of future performance.

As if it needed restating, leadership is not just a science; it’s an art, too.

There’s another problem here. Data and events, when analysed, tell you ‘what’ something did, but it doesn’t explain ‘why’ it did it.

We need business to start looking into the future and joining things up instead of rooting everything in the recent past. Of course, prediction is impossible, but a greater degree of ‘preparedness’ is possible. What is required to be better prepared for an uncertain future?

The facts do not always speak for themselves because imagination is more powerful than knowledge.10 There are many ways to be more imaginative, but business must engage in practices that it may find uncomfortable, such as case scenarios. No leader is inclined to use imagination when they could be using cold hard logic. Scenarios drive fund managers insane because they have less time to waste on speculation. The simple approach is therefore to take the opposite side of any sure bet. If the market consensus is that Clinton wins the Presidency, Britain stays in the EU, NATO and Russia never engage in military confrontation, then it’s always worth simply asking the opposite.

It’s been said before, but the difference between management and leadership is that the former learns how to do things right. The latter learns how to do the right things. They sound and look very similar words, but in fact they are very different. The latter tends to concentrate on the past, the former on the future.

In his book The Metaphoric Mind: A Celebration of Creative Consciousness,11 Bob Samples said:

The metaphoric mind is a maverick. It is as wild and unruly as a child. It follows us doggedly and plagues us with its presence as we wander the contrived corridors of rationality. It is a metaphoric link with the unknown called religion that causes us to build cathedrals – and the very cathedrals are built with rational, logical plans. When some personal crisis or the bewildering chaos of everyday life closes in on us, we often rush to worship the rationally planned cathedral and ignore the religion.

This was summarized later and often falsely attributed to Einstein as: ‘The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honours the servant and has forgotten the gift.’

Analysis versus parenthesis

What if we have become too dependent on our Western Reductionist left-brain process? Has it spawned knowledge acquisition that simply feeds us more about what we already know? How could this have happened when the internet has given us so many great things? Like all great advances of mankind, it’s not about what it does. It’s about how it’s used. The atom bomb may have been the most destructive weapon ever invented, but maybe that’s why the peace has been kept so long? The truth, as ever, is more complex. The internet has created equal and opposite effects. It is both good and bad. Its effects are paradoxical.

Let’s look more closely at the positive, as well as negative, effects of information. If we care to use it that way, information gives us visibility and then transparency. The more information we have, the more we can understand. This is a well-trodden path and perhaps the genius of the internet as a knowledge- and experience-sharing device.

The opposite effect, though, comes when we allow the internet to be our main source of communications and server of news. It interrupts us, narrows our parentheses and then causes us to shorten the time we spend speaking face-to-face.

Well, so what? Who cares if conversation dies? Well, when you lose the ability to converse, you also lose negotiating skills, the ability to solve emotional problems and the ability to listen to ordinary people. A factor in leadership popularity and respect is the time taken by leaders to say hello and chat to even the most junior people in an organization.

Worse still, when taken at the global level, the narrowed outlook then leads to gross levels of ignorance and, as we’ll see later, impatience and bigotry. The net result of this cocktail is a revolutionary fervour driven by half-digested news and a narrowing parenthesis caused by short-termism, ignorance and intolerance.

We have been here before several times in history. The Bourbon monarchy in France lasted for hundreds of years but was in part helped on its way by the social media equivalent of its day – pamphlets. These were scurrilous, cheap to produce, opinionated and widely circulated. When combined with the agrarian food crisis of 1789 and an ineffective monarch, the conditions for an uprising coalesced.

This is similar to the social media of today, but this alone is not enough to trigger a revolution. This requires a catalyst of a more existential nature. In 18th-century France, it was the failure of the agriculture that drove food prices up at a time of discontent. The social media of the time, though, made sure people were aware of the event by feeding them short, scurrilous material, sometimes in pictorial form.

We’re seeing the same phenomena today. People may be unable to read detail in depth, but it seems they’re also becoming more unwilling. Newspaper readership is in decline. Television consumption is becoming on demand and personal. The patterns are becoming harder to spot.

This should be no surprise. If we were analysing climate change, we would not look at the weather for data. The view is too close. The same is true of news. To understand it, we must ask through what lens we see it. If it’s through the daily deluge of news stories, it’s likely to make no sense at all. To make sense of it, we need to zoom out to a higher level so that we can look across to take into account everything that is happening in the world, from geopolitics to economics to sociological analysis and key cultural changes. Sometimes, the more we analyse a subject, the less sense it makes. This is why an opposite logic needs to be applied. This involves zooming out or reframing to a higher context. This way, we can join the dots to get a clearer view of the issues in context.

We need a new framework for understanding that permits us to see patterns, which in turn improves our ability to anticipate. Perhaps the one thing that machines will never be able to replicate is the subtle nuanced pattern recognition that humans are capable of. A human might be able to view Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, listen to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (the ‘Pastoral’), smell new-mown grass and think of ice cream and a happy time spent with friends. Computers cannot do this yet and if they ever could, it would be the last area they would conquer.

Humans are also good at contextualizing knowledge, particularly if they have a wide generalized knowledge. If knowledge begets knowledge, then we can say that what makes people understand is the ability to add more to an existing knowledge structure. To do this necessarily involves the perspective to see where the new knowledge fits. Different people will file different subjects into different parts of their structure. The earlier this starts, the easier the knowledge acquisition process becomes.

Our socio-economic perspective also dictates our understanding

The extent to which people understand depends heavily on what questions they ask. In Ian Leslie’s book Curious: The Desire to Know and Why Your Future Depends on It, he points out that children from lower socio-economic groups are far less likely to question authority than those from higher ones. This is not just about the extent to which the child is encouraged. It’s also about the child’s attitude towards authority figures.12 Middle-class kids begin life with more sense of entitlement and with that a willingness to challenge authority, ask questions and persist until they get answers. Adults who don’t ask questions to challenge authority learn this behaviour at an early stage.

Another key factor that inhibits questions is fear. This could be fear of criticism, not wanting to look stupid or being thought to be dissenting. This is important for leaders to understand. Dissent is not a sign of weakness. On the contrary, we need to encourage it to maximize the resources of the organization. The more lookouts the ship has, the less likely it is to collide with the iceberg. This means we need to listen to opinions even when we don’t like their provenance.

Invariably, the process of questioning is about how things join up at the bigger level. The questioning process starts with the silent dialogue that comes in contemplation. It is not easy to do this when faced with the cacophony of the overload. Yes, paradoxically, withdrawing from all the noise actually helps us achieve a greater understanding of it by contextualizing. The torrent of new information washes around our knowledge structures and many report the phenomenon of having learnt one thing only to have forgotten another. Our understanding of the world is limited if we try to make sense of it day by day. The overload thus has profound effects on our thinking. By swamping us with information, it’s removing the time and opportunity for asking questions, and this is the leader’s most important job.13

It’s difficult to escape an unpleasant conclusion here. Information may at once be enhancing our understanding while diminishing our presence and capabilities. It can help leaders understand, but it can also undermine their curiosity and prevent them from being effective leaders.

How this changes the leader’s mandate

Leaders have got to their position by making data their friend. In the same way, golfers get to a basic level of proficiency by trying hard. There comes a point, though, in all golfers’ path of progression when they need to stop trying and relax. They need to use another approach.

The same is true of leaders. Yes, data are important to get you to a certain level, but after that, there’s no point waterboarding yourself with data. You need to work out whom to talk to and whom to listen to. Yes, leadership is about conversation, not just communication. The former allows you to negotiate and resolve problems. The latter is just data.

What is true for the individual is also true of organizations that exist at a nexus of information. Managing communications has not only become a profession with many people who are responsible within an organization, it’s also become a large part of the leader’s role. Even at the very basic level, the increased transparency challenges the leader’s mandate and responsibility. The wider access to information encourages participation and democracy from shareholders, community members and voters. No wonder business leaders are behaving more like politicians. Like politicians, however, no business leader can provide a running commentary or consultation on every decision to everyone all the time.

So how much do they tell you and when? This is a constant problem of judgement of which issues to engage with and when. Sometimes, leaders choose to hide behind the waterfall of news, with the most dangerous times being when the flow dries up during holiday periods.

Never was this truer than in the world of politics, where some leaders have become so frustrated by threading their messages through the media that they decide to go direct. The best example of this is President Trump. In this case, Twitter has created an unfiltered and direct channel where everyone can hear the President talking in his own words – for good and bad.

Speaking with immediacy subjects the source to the inverse relationship between speed and truth (see Figure 1.1). If the input source of the data is faulty, then so will the output be, too.

Social media can also be dangerous in this respect when giving access to leadership. Let’s call this the ‘Wizard of Oz’ syndrome where the perception of the leader varies inversely with the access granted. Familiarity can breed contempt.

Spotting the signs of a waterboarded leader

The physical effects of overload are easy to spot. Leaders find it hard to concentrate. They’re easily distracted. They answer all e-mails all the time and pride themselves on fast turnaround. They vacillate and often request yet more information. They come to conclusions astonishingly quickly. They fail to converse and pick up anecdotes. Sometimes, this is accompanied by a display of supreme self-confidence. Ignorance can be very reassuring.

QUICK TIP Leaders should create ‘no zones’ of up to 45 minutes where they cannot be interrupted. This requires discipline, but it also pays dividends.

What are the leadership safeguards against a narrowing parenthesis brought about by overconfidence or over-reliance on analysis? First is to be able to recognize that logic and plans are very convincing, but as Marshal Suvarov said: ‘No plan survives contact with the enemy.’ Perhaps Professor Ian McGilchrist best sums up the power of the analytical mind14 this way: ‘the left hemisphere’s talk is very convincing because it shaved off everything that it doesn’t find fits with its model and cut it out. This model is entirely self-consistent largely because it’s made itself so. The right hemisphere (the imagination) doesn’t have a voice and it can’t make these arguments.’

In other words, we need to keep imagination and doubt alive in the boardroom. Most leaders do not attain office by displaying doubt. It’s usually the opposite. The doubting Thomas tends not to thrive. This is why the role of non-executive directors, even in privately held companies, is essential. Their job is to ask questions, not confirm assumptions. This ability to question constructively is an important and subtle skill.

College-educated people are taught to question and critique often in a direct, sometimes brutal way. But questions needn’t be so. Questions are a way of transmitting a concern or raising an issue without making a statement. ‘Are you concerned about?’ is not the same as ‘You should be concerned about’. The implication, though, is subtly different.

In Ian Leslie’s book, he points out that ‘The future belongs to people who are curious’.15 This is an important point. Questions such as ‘Why are we doing this in such a conventional way?’ or ‘What happens if this doesn’t go according to plan?’ need to be asked. Perhaps the biggest point he makes is that the smarter the internet gets, the dumber we become. We don’t need to know how to add up when we have a calculator. We don’t need to know facts when we have the internet. The smarter the search engine, the dumber the questions are allowed to be. Leaders need to ask intelligent questions.

Leslie describes this time as: ‘Rather than a great dumbing-down, it’s likely we are at the beginning of a cognitive polarization – a division into the curious and the incurious. People who are inclined to set off on intellectual adventures will have more opportunities to do so than ever before in human history; people who merely seek quick answers to someone else’s questions will fall out of the habit of asking their own or never ask them in the first place.’

There’s an important point here. The presence in volume of a commodity, eg data, is in no way a reflection of its likelihood to be used. Anything present in abundance is likely to have diminished values. This applies as much to data as it does to opinions.

So, at once, information can provide greater visibility and hence caution, but also the complete opposite. The more dependent on analytical data we become, the more convinced we are that the numbers alone are enough. Doubt is banished and we become ‘data driven’.

Conclusions

Since the turn of the century, we’ve seen a massive increase in information overload. This is having both good and bad effects, some of which are unforeseen and some are paradoxical. The data overload forces us to filter towards information we see as important or relevant. This means we hear a lot more about bad things and less about good. It also creates a binary approach as we summarize at speed to decide whether something is good or bad, relevant or not. This is changing behaviour, not always in a good way. The longer-term, more qualitative information is often missed, for two main reasons. The interruptions force us to move faster, thus prioritizing only what we need right now. It also forces us to an analytical mind set because when we are constantly interrupted we operate in ‘compare, contrast, analyse’ mode. This is the left-brain process which focuses on the short-term, quantitative and narrow goals. This narrowed focus means we can miss vital information which may be at the parenthesis of the framework. This can lead to overconfidence in the numbers and logic alone and an unshakeable belief in ‘rightness’ or a complete absence of doubt. This increases risk and marginalizes long-term qualitative thinking and ultimately diversity in leadership. This is because leadership becomes less qualitative and less focused on intangibles such as long-term community interests, gender, ethnicity and so on.

The implication is that of course information can be useful and a great boon for efficiency. Unfortunately, it also comes with side effects which have a negative impact on behaviour. The overwhelming amount of information leads to overload which narrows our attention into more analytical, short-term, tangible thinking at the expense of longer-term, softer, less measurable qualities. We may not be immediately aware of this, but over time the change is becoming clear.

Endnotes

1 Lewis, C (2016) Too Fast to Think: How to reclaim your creativity in a hyper-connected work culture, Kogan Page, London

2 https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/05/22/solve

3 http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Email-Statistics-Report-2014–2018-Executive-Summary.pdf

4 http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Email-Statistics-Report-2014–2018-Executive-Summary.pdf

5 http://fortune.com/2012/10/08/stop-checking-your-email-now

6 https://www.inc.com/john-brandon/science-says-this-is-the-reason-millennials-check-their-phones-150-times-per-day.html

7 http://www.businessinsider.com/the-messaging-app-report-2015–11

8 https://www.twilio.com/learn/commerce-communications/how-consumers-use-messaging

9 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2092432/MailOnline-worlds-number-Daily-Mail-biggest-newspaper-website-45–348-million-unique-users.html

10 https://manyworldstheory.com/2012/11/26/einsteins-imagination-is-more-important-than-knowledge

11 Samples, B (1976) The Metaphoric Mind: A celebration of creative consciousness, Addison Wesley Longman, Reading, MA

12 Leslie, I (2015) Curious: The desire to know and why your future depends on it, Basic Books, New York

13 https://hbr.org/2017/01/being-a-strategic-leader-is-about-asking-the-right-questions

14 https://www.ted.com/talks/iain_mcgilchrist_the_divided_brain

15 Leslie, I (2015) Curious: The desire to know and why your future depends on it, Basic Books, New York