CHAPTER TWO

Understanding a New Type of Economics

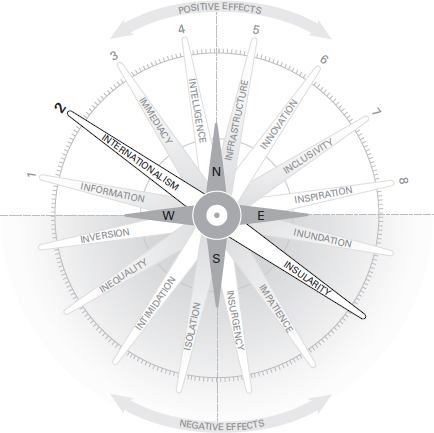

Internationalism and Insularity

This chapter will help leaders strengthen their awareness of the world economy as it actually is, not as it was, or as one hopes it might be. This is vital if employees, customers and even regulators are to trust them. Leaders who rely on out-of-date notions about the world economy are not only unlikely to inspire confidence, they’re also a danger to investors and employees alike.

The barrier to situational fluency is the ephemeral distraction. Often, we’re too busy dealing with the waves to see the tide, which is why we must find time for situational fluency – it’s the leader’s job to know where they are and where they’re going. Leaders are often too busy with their everyday business to notice the changes on the macroeconomic horizon. They may fall back on commonly accepted fallacies such as ‘all the manufacturing jobs are moving to China’ or ‘interest rate hikes cause stock markets to fall’. Like all of us, leaders are products of their past and under pressure revert to past behaviours.

This ‘avoidance of regression’ also applies to leaders’ thinking. They achieve success on their logic and drill-down ability. After that, they need a wider view to get the full context. For example, in theory, more connected global markets can make economies more efficient. In actuality, the increased trade links may create internationalism, which itself is the provenance of insularity as a backlash.

Too many leaders missed the so-called unpredictable events driven by populism such as the election of Donald Trump, the decision to Brexit, the result of the last General Election and so on. They missed the rise of social media and still hesitate to empower their teams to manoeuvre freely in that space.

QUICK TIP Data are not the only truth. Leaders need to walk the floor and talk to as many sources as possible. Communication and data are not enough. Conversations and opinions matter. Trust the mood, not just the maths. Leaders can pick this up by using social media as a listening tool.

The macroeconomic landscape is especially important for leaders because they need to understand into the future. They may work in organizations that are insular, but without an understanding of the world economy they will make mistakes, which are remembered, amplified and scrutinized more than ever. It’s OK to make mistakes. Everyone does, but too many mistakes create doubt, delay and damage.

Leaders trade on experience. They should also deal in hope.1 It’s what defines them. The past, though, is not a comprehensive guide to the future. For instance, many leaders grew up in a post-Berlin Wall world. That brings certain assumptions that may not still be valid. It’s always hard for any leader to recognize that much of what they know may no longer apply. The first task of enlightened leadership is, therefore, cultivated doubt. Opinionated certainty is the hallmark of mediocrity.

Of course, data still matter, but increasingly so does imagination, too. We live in a world economy where the data and the facts seem increasingly to contradict each other. For instance, we may think people are broadly better off after years of income growth. These data, viewed in isolation, don’t tell us the whole story if, for instance, inflation is running above income growth. People may believe the world economy is not serving them even as it has lifted more people out of poverty than at any other time in history. Leaders need to constantly re-examine assumptions and distinguish between what the data indicate and how people actually feel. In a similar way, government says there is no inflation but people see rents, healthcare costs and the general cost of living all rising. This creates suspicion and cynicism. It undermines confidence.

The nature of data is also changing. Countries, companies and communities currently rely on paper forms to find out how the economy is doing. That will increasingly be replaced by automated data collected from sensors. In the future, it will be uploaded into blockchain structures that are both immutable and independently verified, giving a high degree of confidence about the authenticity and reliability of the data. More about this later. Real-time sensors may reveal what the public already know – that governments and companies have not always been as honest or transparent as had been assumed. In other words, the freshness and accuracy of data will bring more questions about conduct.

How can leaders better manage a fast-changing macroeconomic environment? The LAB’s answer is that they should stop trying to predict the future and start preparing for it instead. There’s a difference between predicting and preparing. The former anticipates one outcome. The latter, however, plans for a range of outcomes. The traditional rational left-brain approach encourages leaders (and commentators) to engage in linear thinking and in predictions. The world, however, isn’t linear; it’s more likely to be cyclical, as William Strauss and Neil Howe pointed out in The Fourth Turning.2 This summer is more similar to last summer, as a season, than it is to spring, the season that preceded it.

In this chapter then, we’ll analyse data but also look at perceptions and feelings. We’ll discuss new ideas and destroy a few myths. This is what we will cover:

- Fear stalks the economic landscape

- Fear has no respect for data

- Offshore revelations

- Avoiders and evaders

- The wrong sort of data

- So don’t tell me there’s no inflation

- How inflation is hidden

- Hedonics

- The topography of inflation

- Meet the cause of inflation – debt, debt and more debt

- Bad leadership hides bad news

- Nothing new under the sun

- In office, but not in power

- Is the internet deflationary or inflationary?

- Time to get nerdy

- The ultimate solution to Inflation – smash it up

- Cryptocurrencies

- A booming stock market

- It’s the same the whole world over/It’s the poor what gets the blame/It’s the rich what gets the pleasure/Ain’t it all a bloomin’ shame?3

- Living in the present, but destroying the future

- Leadership implications of these economic changes

- Conclusions

Fear stalks the economic landscape

The persistent feature of the economic landscape is that it keeps changing. It is the one thing leaders can count on, but some leaders don’t see change because they don’t look for it. Perhaps there are good reasons. As the US writer of social protest novels, Upton Sinclair, pointed out, the problem with change is that: ‘It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.’4 Schumpeter called the process of economic change ‘creative destruction’.5 He assumed change would destroy some businesses and some jobs but it would also create new ones. Today, people are not so sure. Now we fear robotics, automation, new start-up competitors and more. We fear because the old ways are not working well, but the new ways are hard to understand. People wonder why everyone is so angry. It’s partly because everyone is so frightened.

When confronted by unexpected change, fear drives people towards one side of the Kythera – the side that involves insularity, nationalism and protectionism. Leaders have other options, though. They can, instead, understand the fear, face it down and inspire people towards the more positive side where we find internationalism, greater communication and trade. This is how they deal in hope. It’s hard, though, for leaders to inspire or guide if their understanding of the economic landscape is out of date. They may end up as surprised as everyone else.

Fear has no respect for data

So, what is the truth about the world economy? There is a palpable sense that some people feel the world economy is not delivering the desired outcome. Income inequality has been rising and the middle classes everywhere are squeezed by rising costs. Many no longer believe that they will become rich before they get old. In the industrialized world, the record levels of debt contribute to a sense of foreboding, guilt and fear, as everyone waits for a reckoning. It was said the debt would kill growth.6 The projections, however, have been proved consistently wrong. Yet we find that almost the entire world is growing better now than it has in years. The world economy has lifted more people out of poverty during the past 30 years than at any time in human history. That’s true globally, but not in the West, where people remain afraid that automation, robotics and artificial intelligence will leave them unemployed and unemployable. The culmination of 100 years of relentless automation, however, is near-record high levels employment. Interest hikes have made stock markets rise, not fall, so far. The paradoxes of heart and head contribute to uncertainty. This weakens confidence and trust in the global economic system and in the leaders who are running it. Irrational fear and fact live comfortably side by side.

Offshore revelations

For this reason, leaders must not only understand the economy better, they also need to understand how people feel. For instance, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the public and leaders alike were shocked to discover the size of the offshore financial market. Prior to this, people had not even registered that there was a shadow banking system. Then, later, with the release of the Panama Papers and revelations about The Appleby Affair,7 experts and the public alike began to realize that the onshore financial system was a fraction of the size of the offshore system (which is $21–32 trillion).

The public don’t understand the banking system, but it’s become clear to them that neither do the regulators and experts. Either they don’t know it as well as they should or, more likely, they just turn a blind eye. Writing in the Financial Times, Gillian Tett explained the rationale in ‘The Copernican Revolution’.8 She described the sudden realization that the financial universe is not as aligned as the public had thought: ‘They no longer know their bank manager personally. An algorithm decides everything now. They feel the financial system is unfairly rigged against them globally and locally, too.’

Avoiders and evaders

This is exacerbated by the realization that tax policy does not treat all participants equally. They see public services cut, while, somehow, big firms and wealthy people take advantage of loopholes in the tax system. The wealthy deposit their monies abroad while small businesses and the poor bear the brunt of higher taxation and compliance costs. Of course, it’s all perfectly legal. It’s a grand joke in taxation circles that tax avoidance is legal, whereas tax evasion isn’t. Such is the depth of accounting humour. Gaming the tax laws and the regulations may be perfectly legal, but it is resented because taxes, regulations and the law always weigh most heavily on those who are least capable of carrying them. Such policies feel unfair and untrustworthy. Even so, big businesses and the wealthy feel unfairly persecuted, while small businesses and the poor feel unfairly burdened. The offshore community complains that it’s too expensive to build the economy of tomorrow if they come back onshore. Onshore resents offshore and vice versa.

QUICK TIP The higher leaders rise, the more they need to understand the perception that somehow the system is rigged. Transparency does not, of itself, ensure trust, but it at least lessens the perception of unfairness.

The wrong sort of data

The revelations about the offshore economy illustrate an obvious truth. Governments are insular and national. The economy is international and global. Data about the economy are domestic but transaction flows are international. Policies in one country can affect economies abroad. International trends may overwhelm national policy. Surely, we have enough data to know what’s what? We are getting better at gathering data and analysing them every day, as we will see in Chapter 6 on technology, yet there remains a problem. Turning to nationalism as a credible response to these sorts of international problems illustrates perfectly that political leadership is seldom, if ever, about logic.

Twentieth-century leaders think in terms of data points. A modern leader needs to appreciate that data are more like a wave. The level of inflation, for example, might be described as, say, 2.3 per cent, but that’s an average across the entire economy. The wealthy may not feel any inflation at all. The poor may feel a very small amount of inflation because it hits them disproportionately hard. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) can be, say, below 2 per cent, but people may be finding it impossible to cover their rent. In other words, it is not as useful anymore to describe the economy with static data points. It is more useful to think about the waves rolling through it. These hit some harder and sooner and others less or later. Economists are happy to drill down into prices, but not to consider the wave of pain that price changes cause.

Consider the price of prescription drugs. The overall inflation rate in the United States in 2017 was 2.2 per cent9 yet the price of a 100 mg tablet of Viagra jumped by 39 per cent. The price of morphine rose by 93 per cent in 2017, when the cost went from $30 for a 25-pack of vials to $58. Another pain killer, Chantix, jumped by 29 per cent in 2017.10 Telling people that their inflation rate is only 2.2 per cent insults their intelligence and undermines their trust. The overall cost of healthcare is also rising. Evercore ISI estimates that the average US family spends some $4,000 per year on healthcare.11 This is expected to rise by 25 per cent in 2018 to $5,000. The problem is so severe that both President Obama and President Trump have made it a central political campaign issue, albeit from opposite perspectives. Three of the United States’ most respected business leaders, Warren Buffet, Jeff Bezos of Amazon and Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan, have jointly announced their intention to introduce a new healthcare system to lower the cost for their collective 500,000 employees.12 This is not a purely US phenomenon. The National Health Service in the United Kingdom is under constant price pressure. Increasingly, citizens are being asked to pay a bigger portion of the public budget on healthcare costs or to pay more for specific treatments.

So don’t tell me there’s no inflation

Housing costs are also rising. Rents across the United States are at a historic high of almost 29.1 per cent of income.13 In New York City, rents have risen 75 per cent since 2000.14 Nationwide, rents have risen by 2.4 per cent in 2017. But hikes in some cities are much greater. In 2017, rent in Portland, Oregon was up by 4.6 per cent, in San Diego 5.5 per cent, in Las Vegas 6.3 per cent and even in Odessa, Texas by 33 per cent.15 The Pew Research Center reported in July 2017 that more US households are renting than at any time in the past 50 years.16 In addition, 79 million US adults are sharing their living space to save on costs because millennial children cannot afford to rent or buy.17

Rents and property prices have been rising all over the world. In Beijing, one study estimated that property prices rose by 1,538 per cent from 2004 to 2016. Housing costs across China, but especially in the big cities, have risen enough to compel Xi Jinping, China’s leader, to take on the problem at the highest level: ‘Houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation. China will accelerate establishing a system with supply from multiple parties, affordability from different channels and make rental housing as important as home purchasing’,18 he said. Elsewhere in the world, it is hard to name a city that has not experienced significant rent increases in recent years. Rent in Sydney was up by 6.5 per cent in 2017. London may be falling slightly but it was still the most expensive city for rent in Europe for three years.19

Groceries and food prices are also important. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization says that food prices rose by 8.2 per cent in 2017.20 The price of every kind of food but sugar went up. Taken together, one can see why people are suspicious of the traditional data. Leaders must be suspicious too, for many reasons.

QUICK TIP Leaders should develop tools that measure the economic impacts on their teams, clients and constituents and not simply rely on or parrot government statistics. Confidence matters more than calculation.

How inflation is hidden

An open-eyed, open-minded leader looks for qualitative insights as well as quantitative data. Qualitative changes are perceptible but too often dismissed. For example, we have seen a clear rise in something called ‘shrinkflation’. A basket of products is measured for inflation by price, not by volume or weight. If the products shrink in size but the price stays the same, technically no price hike has occurred. But people aren’t stupid, they know what that means. You can see this in everything from the reduced amount of cereal in a box to smaller-sized chocolate bars. You can see it in the form of ever-larger apertures in toothpaste tubes21 and powders of various sorts. The purpose of these changes is to make the consumer use up the product faster and to pay more per weight. Toilet paper and paper towel rolls have ever-larger tube centres and ever-fewer sheets,22 while the price remains the same. There are fewer potato crisps in the bag and cookies in the box. Bottles of liquids such as perfumes have ever-larger dimples on the bottom that displace the product and create the illusion of more inside than there is. Shrinkflation is not restricted to retail products. Apartments are shrinking, too. Micro apartments are smaller than anything we lived in before but cost more per square foot. Shrinkflation is a signal that tells us that companies are facing higher costs. It is a signal that price pressures are starting to build. Attentive leaders cannot ignore these trends because they affect their followers. They must show they care about the quality of life. The data may say there is no inflation but your followers may be having a terrible time paying their rent.

Hedonics

Leaders should be aware of the methods used to calculate prices because the quantity of inflation is not the same as the quality. Central banks are the most trusted sources of information on inflation and deflation. They have long used hedonic methodology to adjust prices for quality changes. In practice, this means they tend to show that prices are falling. Each year the new Apple computer typically has vastly more computing power than before. This means that the quality has increased even though the price has not risen. Central bankers count this as a price decline. Car prices are similar. You get many more features in your car now for the same old price. Some people might prefer an Apple computer with less power at a lower price, but that is not on offer. They might prefer a car that has fewer features and a lower sticker price, but that is not on offer either. In these ways, inflation is hidden and built in. The buyers know this but are helpless to change it. Hedonics creates the image of a deflationary world while consumers still experience inflationary forces.

The topography of inflation

Inflation and deflation are unevenly distributed in the world economy. The rich don’t feel inflation because their wealth protects them from it. Economists (often not quite living in the real world) say that people can buy cheaper food if prices rise. If steak goes up, they can swap it for, say, tofu. The problem arises when the price of protein rises so much that the poor are forced into cheaper calories. This almost always means emptier calories. Inflation can push the poor into malnutrition or no nutrition at a time when the price pressure itself is not universally acknowledged. The economy touches a leader’s followers in many ways. Junior staff may be feeling inflation due to their rising rentals in big cities at the moment that senior staff are enjoying the mortgage relief from record low interest rates. One employee is working hard just to stay in the city and in the job despite having lost all hope of ever owning a home. Another employee in the same firm now owns a home outright and uses the proceeds from the rising stock market to decrease mortgage costs and to take more expensive vacations. Astute, alert leaders will not care just about the data points the economy sends them. They will also care about the quality of life they are providing. Good leaders feel for the ways in which the economy impacts their followers.

Meet the cause of inflation – debt, debt and more debt

There’s no two ways around it – debt destroys the social fabric and breaks the promises that hold us together. Debt is what causes governments to institute lower levels of social services and higher levels of tax. Debt burdens typically force governments to raise the retirement age and the cost of transportation, and to reduce public services in healthcare and schools. In this way, debt breaks the promises leaders make.

Global debt is now three times the level of global GDP. The debt stood at 318 per cent of global GDP or some $233 trillion as of the third quarter of 2017.23 The horrifying facts are constantly repeated in the press and by international organizations. The IMF says that China’s debt levels ballooned to 234 per cent of GDP in 2016.24 Local government debt continues to expand at what appears to be an unsustainable pace. In 2017, the increase doubled on the previous year.25 Forty-six per cent of US workers are so indebted that they don’t have $500 in savings to cover an emergency.26 A study by the Royal Society of Arts echoed this and showed that around 70 per cent of British workers are chronically broke, with some 32 per cent having less than £500 in savings.27 Being in debt and being broke give rise to anger. More and more the public turn this anger on leaders in the form of populism.

The debt problem is overwhelming most major economies in the world, from Japan to almost all European nations. The debt burden encompasses both public and private sectors, although the former dwarves the latter because governments were forced to buy private sector banking assets to bail them out. There are some who think the debt does not matter. Others think governments are spending far beyond their means. Figure 2.1 shows a chart of government debt as a percentage of GDP, which is the usual measure of government indebtedness.