Shortly before noon on August 15, 1945, Kim Eun-kook turned on the radio. His grandfather told the young boy that an important announcement was to be broadcast at noon and that they would listen to it together. The day before, the police had come through his neighborhood in Hamhŭng city to remind everyone to listen to the radio because the emperor would be speaking. “The emperor was going to say something about a ‘fantastic weapon’ invented by Japan,” the old man told the boy. The weapon was supposed to “wipe out the Americans in no time” and win the war for Japan.

Eun-kook and his grandfather sat together on the veranda while they listened to the crackling notes of the Japanese national anthem. Although they had been reminded by the police to face the radio and touch the floor with their foreheads when the emperor spoke, they did no such thing. Both remained sitting upright and cross-legged. Then the emperor spoke. Eun-kook translated the speech for his grandfather because the old man could not understand Japanese. At first the young boy had a hard time making sense of the emperor’s words. Neither he nor his grandfather, or any of the emperor’s subjects for that matter, had ever heard the voice of the emperor before.

“Well, what is he saying?” asked the old man. “Has he said anything important yet?” The boy shook his head. The emperor spoke in a complex form of Japanese that few people could understand. Eun-kook turned up the volume. Suddenly, he straightened up, jolted by what he had just heard. He told his grandfather that the emperor had just announced that Japan had lost the war and would surrender unconditionally to the Allied Powers. The old man grasped the boy and began sobbing. Hearing the cries, the boy’s grandmother ran out to the veranda. She too began weeping openly when she learned the news. Before the emperor had finished speaking, Eun-kook abruptly turned off the radio. He ran outside and took down the Japanese flag that hung by the door. Showing it to his grandmother, he asked what he should do with it. “Burn it,” she said.1

For tens of millions of Koreans who listened to the Japanese emperor’s announcement that afternoon, August 15 was a day of joyous celebration, marking freedom from thirty-five years of colonial servitude. Despite the fervor of the moment, however, liberation carried a heavy price. Korea was not liberated by Koreans, and so Korea was subjugated to the will and wishes of its liberators. While thousands of Japanese flooded the trains and ferries to go back to Japan, the Americans and Soviets took control. American planners had only a vague notion of what would happen to Korea after Japan’s collapse. Korea had never been important to the United States. Forty years earlier, President Theodore Roosevelt had taken a cold-eyed, realistic view of the situation in northeast Asia. He had accepted Japan as the regional hegemon and praised Japan’s success and progress from a feudal state to world power in less than four decades. Roosevelt’s recognition of Japan’s “special interest” in Korea after it defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5), a war he helped end by negotiating a peace treaty, for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize, had facilitated Korea’s colonization. For this Japan had agreed to recognize America’s special interest in the Philippines.

Theodore Roosevelt’s complicity in Korea’s colonization would be rectified in 1945 by his cousin’s vision of a free and independent Korea. After World War II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) embraced a new world order that would fundamentally transform the status of Japanese and European colonies. He advocated the virtues of representative democracy, aid to the oppressed, free trade, and open markets. But before full independence could be granted to Korea and other former colonies, FDR envisioned a period of trusteeship by the Allied Powers to oversee internal affairs and prepare them for independence and self-rule. He was also careful to ensure that postcolonial nations would not orient themselves against American interests. Although at first opposed, Churchill agreed, because the Cairo Declaration did not specifically infringe on Britain’s own colonial holdings and named only Korea for trusteeship. The Declaration, published on December 1, 1943, contained the first Great Power pledge by the United States, Great Britain, and China to support Korean independence “in due course.” Stalin responded positively about the trusteeship idea when FDR told him about it at their meeting in Tehran shortly after the Cairo Conference, but Stalin thought the period of trusteeship should be as short as possible.2

The proposal, however, was ill defined and lacked specifics on how a joint trusteeship in Korea was supposed to work. In the end, it was not resolved through an agreement, but by military events on the ground. More than FDR’s grand design for a new world order, it was the sudden collapse of Japan that would determine Korea’s future, as well as the post–World War II order in Asia. At Yalta in February 1945, as the end of World War II approached, FDR and Stalin agreed that Soviet forces would liberate Korea while the Americans would invade the Japanese mainland.3 Stalin expected much in return for liberating Manchuria and Korea. American General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) for the Japanese occupation, warned, “They would want all of Manchuria, Korea, and possibly parts of North China. The seizure of territory was inevitable, but the United States must insist that Russia pay her way by invading Manchuria at the earliest possible date after the defeat of Germany.”4 Roosevelt tacitly agreed. Without consulting Churchill or the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi), FDR made a secret deal with Stalin conceding the Kurile Islands, the southern half of Sakhalin, and special privileges in Manchuria for Soviet entry into the war against Japan.5

By the time the Potsdam Conference was held in July following Germany’s surrender, the situation had changed dramatically, owing to the death of FDR in April and the success of the atomic bomb program. The main goal of the Potsdam Conference was to establish a vision for the postwar world order, but the bomb’s existence had complicated matters between the United States and the Soviet Union. American Secretary of War Henry Stimson told President Harry Truman at the conference that the atomic bomb would be ready in a matter of days for use against Japan. Truman then approached Churchill to discuss what they should tell Stalin. If they told him about the bomb, he might try to enter the war against Japan as soon as possible. The bomb provided the possibility of circumventing a costly invasion of Japan, and the need for Soviet help became far less pressing. Truman decided to tell Stalin as late as possible and to describe it in the vaguest terms, not as an atomic bomb but as “an entirely novel form of bomb.”6

Stalin, however, had already known of the bomb’s existence for some time.7 Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet ambassador to the United States at the time, recalled that Stalin was angry at the Americans’ apparent lack of trust. “Roosevelt clearly felt no need to put us in the picture,” Stalin later told Gromyko. “He could have done it at Yalta. He could simply have told me the atom bomb was going through its experimental stages. We were supposed to be allies.”8 Stalin told Truman that his forces would be ready for action by mid-August. With the atomic bomb on the table, however, Stalin secretly decided to advance the date of the attack by ten days, as Truman and Churchill had feared. He would outmaneuver the Americans, who had hoped to force Japan’s surrender without the Soviet Union’s entry into the war. At 11 p.m. on August 8, two days after “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. Soviet forces began crossing into Manchuria an hour later on August 9. For just a week’s worth of fighting, the Soviet Union reclaimed the territory lost in the Russo-Japanese War. Truman had lost the race to induce Japan’s surrender before Soviet tanks rolled into Manchuria.9

Japan’s sudden collapse caught everyone by surprise. The fate of the Korean peninsula suddenly became of interest to the Americans. The Soviet advance through Manchuria was so rapid that it would be able to occupy all of the Korean peninsula before the Americans could get there. It was one thing to give up Korea to save American lives and quite another to simply hand it over to the Soviets. The United States realized that talks of joint trusteeship would be moot if the Soviets occupied all of Korea. The Americans decided to approach the Soviets with a proposal to divide the peninsula into American and Soviet zones of occupation, with the ultimate goal of creating a unified Korea under joint American and Soviet tutelage. But before such a request could be offered, a decision on where to divide the peninsula had to be made. This task fell on two U.S. Army colonels from the War Department staff, Charles Bonesteel, future commander of U.S. and UN forces in Korea in the late 1960s, and Dean Rusk, future secretary of state under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Using a National Geographic map and working late into the night under great pressure, they chose the 38th parallel. Rusk later recalled that “we recommended the 38th Parallel even though it was further north than could realistically be reached … in the event of Soviet disagreement,” but to the surprise and relief of everyone, Stalin agreed.10

Why did he agree when Soviet forces could have easily occupied the entire peninsula? Rather than territorial gain, Stalin’s main concern was to eliminate Japanese political and economic influence in the region. “Japan must forever be excluded from Korea,” stated a June 1945 Soviet report on Korea, “since a Korea under Japanese rule would be a constant threat to the Far East of the USSR.”11 Stalin accepted a divided occupation in Korea because the Americans could help in neutralizing Japan. Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War had forced Russia to forfeit its interests in Korea and Manchuria for nearly half a century and to give up Russian territory in southern Sakhalin. Japan’s demise gave Stalin the chance to regain Russia’s pre-1905 position in the Far East. As Stalin triumphantly noted in a radio speech on September 2, the date of Japan’s formal surrender, “The defeat of the Russian troops in the period of the Russo-Japanese War left grave memories in the minds of our people. It fell as a dark stain on our country. Our people trusted and awaited the day when Japan would be routed and the stain wiped out. For forty years we, the men of the older generation, have waited for this day. And now this day has come.”12

The first weeks of Soviet occupation did not bode well for the Koreans. The soldiers were not the Red Army’s finest and lacked discipline. The initial wave of Russian troops behaved with widespread and indiscriminate violence toward the local population. Within days of their arrival, disturbing reports of rape and pillage filtered into the American zone from beleaguered Japanese and Korean refugees.13 Harold Isaacs of Newsweek described a harrowing visit to Sŏngdo city, about fifty miles north of Seoul and now known as Kaesŏng, which the Russians had mistakenly occupied and then retreated from as it lies south of the 38th parallel. During their ten-day stay, the Russians had thoroughly ransacked the city’s shops, wineries, and warehouses.14 Moscow claimed northern Korea’s economic resources as compensation for its week-long war against Japan. Industrial complexes in North and South Hamgyŏng provinces were particularly hard hit as Russian forces dismantled steel plants, textile mills, and dock facilities and shipped the parts back to the Soviet Union.15

Reports of the Soviet pillaging led many Americans to believe that support for the Russians in northern Korea would be short-lived. Remarkably, however, Korean resistance to Soviet occupation did not last long. Stalin ordered the commander of the Soviet occupation force to take control of the situation and “to explain to the local population … that the private and public property of the citizens of North Korea are under the protection of Soviet military power … [and] to give instruction to the troops in North Korea to strictly observe discipline, not offend the population, and conduct themselves properly.”16 By late September 1945, discipline markedly improved, and the harassment of the local population ended as the Soviet occupiers quickly began to establish control over their zone.17 Ethnic Koreans already in service with the Soviet government and others were mobilized to help with the administration of the Soviet zone. While the occupation of northern Korea found the Soviets almost as unprepared and untrained for the task as the Americans were in the south, the available pool of these Soviet Korean citizens who were committed communists, spoke both Korean and Russian, and understood the political and cultural nuances of Korean society made the transition to Soviet-occupied northern Korea a fairly easy one.

The history of the Soviet Korean community is intimately intertwined with the turbulent history of Russo-Japanese relations. Although Korean emigration to the Russian Far East goes back to the mid-nineteenth century, the flow increased significantly after the Russo-Japanese War and Japanese colonization of the peninsula. Tens of thousands of Koreans during this period fled the Japanese colony and sought refuge in Russia. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, many Korean communists joined the Bolsheviks in Russia’s civil war. Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 and Stalin’s pledge to aid Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces against the Japanese further consolidated Soviet Koreans behind the Soviet regime in their fight against Japan. In 1932, all Soviet Koreans were granted Soviet citizenship, but it did not spare them from Stalin’s Great Purge of the late 1930s. Japan’s invasion of China in 1937 was used as a pretext to forcibly relocate, at great human cost, the entire Korean community away from the Soviet Far East on the suspicion that they were instruments of the Japanese.18 Between September and November 1937, some 180,000 Koreans were involuntarily resettled in the Soviet interior in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.19 It was from these same communities that Stalin later recruited ethnic Koreans to help administer the Soviet zone.

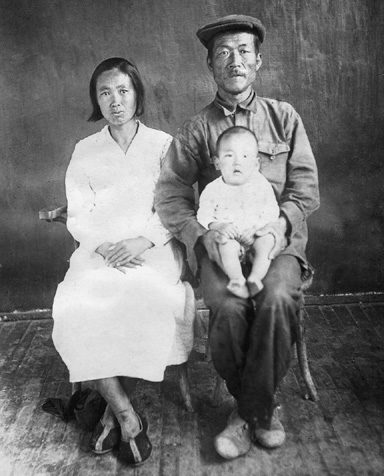

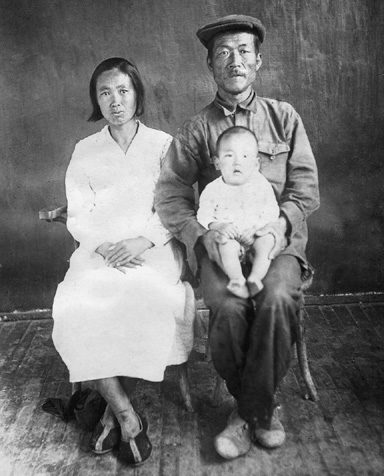

Ethnic Korean families living in the Soviet Far East, like Hum Bung-do and his wife (above), were the first among many ethnic minorities to be subjected to the hardships of deportation by the Soviet leadership in 1937. Their resettlement in Kazakhstan and Central Asia also offered a partial solution to depopulation in these areas. Forced collectivization, famine (1931–33), epidemics, and other hardships had killed some 1.7 million people in Kazakhstan alone. These losses created severe labor shortages, which were partly filled by the new Korean settlers. (COPYRIGHT KORYO SARAM: THE UNRELIABLE PEOPLE)

The first cohort of Soviet Koreans arrived in P’yŏngyang in September 1945 to help set up the Soviet Civil Administration (SCA), the Soviet military government for the northern zone. “We call this period the ‘Age of the Translators,’ “ wrote Lim Ŭn, a former North Korean official who defected to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. “The interpreters were powerful ambassadors of the Soviet Army Headquarters.”20 By quickly replacing top colonial Japanese and Korean officials and civil servants, the Soviets righteously claimed a sharp break from the colonial past. Marshal Aleksandr M. Vasilevsky, the commander in chief of the Soviet forces in the Far East, put Korean anti-Japanese sentiments to work on behalf of his troops. On August 9, the same day the Soviets invaded Manchuria, Vasilevsky issued an “Appeal by the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet troops in the Far East to the People of Korea” that linked Korea’s anti-Japanese colonial struggle to Russia’s struggle against Japan:

The dark night of slavery over the land of Korea lasted for long decades, and at last, THE HOUR OF LIBERATION HAS COME! The Red Army has, together with the troops of the allied armies, utterly destroyed the armies of Hitler’s Germany, the permanent ally of Japan … Now the turn of Japan has come. Koreans! Rise for a holy war against your oppressors … Remember, Koreans, that we have a common enemy, the Japanese! Know that we will help you as a friend in the struggle for your liberation from Japanese oppression!21

While the occupation was overseen by Soviet officers, law and order was maintained by a Soviet Korean bureaucracy that worked directly with the Korean population. Soon after liberation, several hundred self-governing People’s Committees sprang up throughout the country, in both the north and the south, to help secure law and order in the immediate aftermath of liberation, but they quickly evolved into local governing groups with their own peacekeeping duties. Rather than banning them as the Americans had done in their zone, the Soviets used them by turning them “into core institutions of the pro-Soviet regime.”22

Senior Soviet officers in Korea were not specialists in foreign affairs, let alone experts on Korea, but many of the key officers were, interestingly, veterans of the Russo-Finnish War of 1939–40, a fact that would later have consequences when the operational plan for the invasion of South Korea was formulated. Marshal Kirill Meretskov, who commanded the Soviet forces attacking Manchuria and Korea and then became chief of the SCA, was a senior commander in the Finnish War and was personally chosen by Stalin for his proven ability in that conflict. “The wily man of Iaroslavl [Meretskov’s headquarters in the Finnish War] would find a way of smashing the Japanese,” Stalin said.23 Another veteran of the Finnish War who played a key role in the occupation was Maj. Gen. Nikolai Lebedev. A political officer with limited military training, Lebedev participated in the liberation of Manchuria and northern Korea and became the head of the SCA in 1947. The most important personage was another Finnish War veteran, Col. Gen. Terentii Fomich Shtykov, head of the Soviet delegation to the United States–Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Joint Commission on Korea, the brainchild behind the creation of the SCA, and the first Soviet ambassador to North Korea. Khrushchev, future leader of the Soviet Union, described him as “brilliant.”24 Shtykov was known as Moscow’s “Mr. Korea.” He was, according to the historian Charles Armstrong, “instrumental in formulating Soviet policy toward Korea, had direct access to Stalin, and exercised close supervision of the political events in northern Korea.”25 Lebedev later said that “there was not an event in which Shtykov was not involved.”26

With the Soviet Koreans working directly with the populace, Soviet authorities were able to control their zone unobtrusively while promoting Soviet policies. Yet, despite their central role in running the Soviet zone, the Soviet Koreans’ influence over the Korean people was limited. Most of them had been born and raised in the Soviet Union and therefore had few if any close personal ties to the land or the people. Thus, there was an early recognition of the need for an indigenous Korean leader who had legitimacy in the Korean community while still being receptive to Soviet influence. The Soviets’ first choice was Cho Man-sik. A devout Christian and nationalist who commanded great respect for his refusal to adopt a Japanese name in the 1940s, Cho was perhaps the most admired political figure in all of Korea and thus could have been an effective Soviet proxy.27 Since the communist movement in northern Korea was virtually nonexistent, its main strength being in the south, there was no pool of Korean communists for the Soviets to choose from. The Soviets hoped to leverage Cho’s popularity and prestige to put together a broad coalition of leftists and nationalists as a base of support for their policies and plans to create a pro-Soviet regime.

It was soon apparent, however, that Cho was not amenable to such an arrangement. Yu Sŏng-ch’ŏl, a Soviet Korean who later became chief of the North Korean army’s Operations Bureau, recalled that Cho opposed Soviet policies and “refused to cooperate with the Soviet Occupation Forces.” Even after Cho’s refusal, “the Soviet Occupation Forces tried to recruit Cho through many different people. However, they were never successful in their attempts, and [because of] this the Soviets lost interest.”28

The other logical choice was Pak Hŏn-yŏng, one of the key leaders of the Korean Communist Party (KCP). But Pak was from Seoul and was neither well known nor completely trusted in the north. “The decisive cause of Pak’s failure,” wrote Lim Ŭn, “was that he was unable to get ‘a sign of wings’ [a check mark next to his name] from Stalin.” The Soviets also discounted Korean communists who had fought with the Chinese communists in the Chinese civil war, because they could not be trusted. Kim Mu-chŏng, more commonly known simply as Mu Chŏng, was perhaps the most prominent member of this faction. He participated in and survived the Long March with Mao Zedong in 1934–35 and was considered by his contemporaries as a “matchless star.” “He won popularity as he was an eloquent speaker of great resources,” observed Lim Ŭn. But it was precisely because of his strong ties to the Chinese communists “that the Soviets felt that they could not trust him.”29 This left one final group of Korean communists who might be tapped, the small band of former anti-Japanese guerillas in Manchuria who had found refuge in the Soviet Far East. Among them was a boyish thirty-three-year-old captain in the Soviet Army named Kim Il Sung. Yu Sŏng-ch’ŏl recalled that Kim had “considerable authority among the … partisans who, along with Kim, had risked their lives conducting anti-Japanese resistance operations … in Manchuria.”30

Compared to Cho Man-sik, Pak Hŏn-yŏng, and Mu Chŏng, Kim Il Sung had far less experience as either a political leader or a military commander. The 88th Brigade at Khabarovsk, to which Kim Il Sung had been assigned as a young Soviet captain, was a reconnaissance unit that infiltrated into Japanese areas to gather information.31 Yu, who met Kim in the 88th Brigade, recalled only one instance when Kim directly commanded a reconnaissance mission: “On June 4, 1937, Kim Il Sung led a group of some 200 partisans … across the border in an assault on the border village of Poch’ŏnbo killing several Japanese police and retreating after obtaining rations and funds from landlords there.” A month after the Japanese surrender, Kim Il Sung and Yu Sŏng-ch’ŏl arrived in Wŏnsan. “At the time,” recalled Yu, “I was not quite sure how the Soviets intended to use us in North Korea, but I believe there was no definite plan. Even at this time, none of us was thinking that Kim Il Sung would become the new leader of North Korea.”32 Still, visible interest in Kim Il Sung was shown when Col. Gen. Ivan Chistiakov, commander of the Soviet occupation army, personally greeted him. The first sign of Kim’s rising star came at a mass rally in mid-October to honor the Soviet Army. It was there that Kim was introduced to the citizens of P’yŏngyang. Cho Man-sik was also asked by the Russians to give his blessing to the event by appearing alongside Kim.

By all accounts the event was a flop. When Lebedev, chief of the SCA, opened the rally and presented Kim as a national hero and an “outstanding guerilla leader,” many were astonished and even angry. O Yŏng-jin, Cho Man-sik’s personal secretary, recalled the public’s reaction:

[The people had anticipated a gray-haired veteran patriot] but they saw a young man of about 30 with a manuscript approaching the microphone … His complexion was slightly dark and he had a haircut like a Chinese waiter … “He is a fake!” All of the people gathered upon the athletic field felt an electrifying sense of distrust, disappointment, discontent, and anger … There was the problem of age, but there was also the content of the speech, which was so much like that of the other communists whose monotonous repetitions had worn the people out.33

The Soviet authorities were alarmed and bewildered by the negative reaction, but they stuck with their choice and thereafter “placed enormous emphasis on improving Kim Il Sung’s image through propaganda activities.”34

In late 1945, Chistiakov announced that the People’s Committees would be allowed to participate in political affairs if they interacted with proper Russian authorities.35 This was followed by a requirement for all “anti-Japanese parties and democratic organizations” to register with the SCA and provide a roster of its members. The SCA was thus able to identify “activists” and control organizations that were deemed potentially subversive. Parties identified as anticommunist or sympathetic to the United States were banned.36 Many Koreans reacted with outrage. In addition, contrary to the hope that the People’s Committees would abolish the state purchase of grains, a policy the Japanese had forced on Korean farmers, no such reforms occurred. Instead, on August 20, the People’s Committees officially announced plans for the state to purchase grain. For the average North Korean farmer, very little had changed before and after liberation.37

On November 23, riots broke out in Sinŭiju, a northwestern city on the Yalu River. Secondary-school students demonstrated against “the provincial police headquarters, People’s Committee, and the provincial [communist] party headquarters calling for the removal of Communist and Soviet military rule.” One account stated that “the police and Soviet troops opened fire killing 23 students and wounding some 700.”38 Soon after the uprising, a stream of people began to flow to the south. From early December 1945, six thousand refugees a day poured into the American zone, straining the U.S. military command’s ability to handle them.39 Student riots in the port city of Hamhŭng on the east coast in March 1946 exacerbated the situation.40 By July 1947, the New York Times reported, nearly two million refugees had moved south from the Soviet zone.41

The Soviets welcomed this exodus, for it removed much of the anti-Soviet and anticommunist factions in their zone. Still, the uprisings in Sinŭiju and elsewhere were warnings to Kim Il Sung and his Soviet backers of the potential hazards from social unrest. Lebedev was particularly alarmed by reports of scattered violence. Political opponents shot and killed the chairman of a township People’s Committee in the county of Haeju, and an ex-landlord attempted to murder a peasant committee member in the same province. There were reports of water tanks being poisoned and a food depot set on fire.42 The Soviet response was to tighten control over political groups and activities. Kim Il Sung declared that social and political unrest had occurred because the Korean Communist Party (KCP) had weak ties to the masses. He called for the merging of “democratic forces” in northern Korea to create a united front. New members needed to be properly screened and trained, and old members vetted to purge reactionary elements. Local cells were brought under centralized party control. By December 1945, the contours of the future North Korean regime had already begun to take shape.43

The Americans faced greater difficulties in governing their zone despite the initial goodwill of the Koreans. Many Koreans were familiar with the American missionaries who had been in Korea since the mid-nineteenth century. Moreover, a large number of prominent Korean leaders in the south, as in the north, were devout Christians. Few believed that American soldiers would act like the Russians and expected, with tremendous excitement, the prospect of independence and freedom.

The goodwill quickly evaporated soon after Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge and his XXIV Corps arrived in September 1945. A capable and blunt-speaking field commander, Hodge went to Korea with the simple goal of disarming the Japanese and sending them back to Japan. With the trusteeship plan still not fully settled, American policy in East Asia was focused not on the occupation of Korea, but on the occupation of Japan. The focus on Japan would have lasting implications for Korea. General MacArthur adopted an “enlightened” policy, treating the Japanese not as America’s conquered foe, but as a new and liberated friend. Arriving in Tokyo at the end of August, MacArthur believed that the occupation should make maximum use of existing institutions to govern “from above” while seeking to induce radical changes “from below.” America, he said, would lead the Japanese by example. Setting out to reform the Japanese of their “backward” and “feudalistic” culture, MacArthur sought to reweave Japan’s political, social, cultural, and economic fabric and revise the very way the Japanese thought of themselves. It was a role he relished.44 But America’s occupation policy for Japan had confusing implications for Korea. If the Japanese were to be reformed and treated as friends, where did that leave the Koreans, victims of Japan’s brutal colonial regime?

Parade welcoming the Americans on September 16, 1945. Many of the welcoming parades also featured Soviet flags as the Korean people were not sure whom their liberators would be. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Hodge did not give much thought to the question since his primary concern was to disarm and repatriate the Japanese. He was also unsure of the reception he and his troops would receive when they arrived in Korea. Colonel Kenneth Strother of the XXIV Corps staff recalled Hodge’s uneasy reaction: “At the time and in the atmosphere which had been generated by four years of combat with the Japanese, the thought of trusting the lives of a small group of American soldiers to the Japanese Army [in Korea] was startling.” Moreover, there had also been some doubt as to whether the Japanese were in full control of the situation in Korea. “The Japanese government was having plenty of trouble between their surrender and the arrival of the American occupation forces,” observed Strother. “As we later learned, a conspiracy against the government to prevent national surrender developed on August 16 into an open revolt by the garrison troops of Tokyo. This was put down with bloodshed, leaving serious question as to the attitude we might expect in the Japanese troops stationed in Korea.”45 The precarious state of affairs in liberated Korea and the potential for violence led Hodge to decide that he would have to rely on incumbent Japanese officials to carry out the essential functions of governance. To his relief, Hodge and his men were received peacefully and courteously, dispelling fears that they might face a hostile or unstable situation in Korea. However, the Koreans reacted with outrage when Hodge announced that Japanese officials, including the hated Governor General Abe Nobuyuki, would continue to administer the American zone. Hoping to placate their anger, Hodge announced that “Abe’s position would be analogous to that of the Emperor of Japan,” meaning that he would “merely be a figurehead.” For a people who had been oppressed by this “figurehead” for the last thirty-five years, these were hardly reassuring words.46

On September 9, Hodge and Abe signed the formal surrender document. As Abe reached over to sign with the pen, he began to tremble. “His complexion suddenly took on an alarming green cast,” recalled Strother. Turning his head away, Abe “vomited quietly in his handkerchief before affixing his own signature.” Hodge was deeply affected. As a professional military man, Hodge respected the Japanese as loyal soldiers and empathized with the pain of their defeat. Earlier, Abe had requested that he and his family remain in the official residence for a few extra days because his wife was ill with pneumonia. Strother recalled that “Hodge, a stern-looking, tough talking man, replied with obvious compassion that the Abes could stay in residence as long as they wanted.”47 Such acts of compassion toward the Japanese, mostly because Japanese cooperation was essential, enraged the Koreans. They deeply resented the Americans treating the Koreans as a conquered people while conferring with the Japanese on the future of their country. They also questioned American motives. Just what kind of liberators would allow a defeated nation to remain in power? What kind of deal was being struck? The situation smacked of the Great Power jostling over Korea that had occurred at the end of the nineteenth century and had led to subjugation under Japan.

The Americans soon realized that retaining Japanese officials was harming their ability to govern. MacArthur wrote to Hodge, “For political reasons it is advisable that you should remove from office immediately: Governor-General Abe, Chiefs of all bureaus of the Government-General, provincial governors and provincial police chiefs.” He concluded, “You should furthermore proceed as rapidly as possible with the removal of other Japanese and collaborationist Korean administrators.” This was easier said than done. Could the Americans govern without the Japanese? H. Merrell Benninghoff, the State Department political advisor to Hodge, thought that the “removal of Japanese officials is desirable from the public opinion standpoint,” but they must be relieved “only in name [because] there are no qualified Koreans for other than the low-ranking positions, either in government or in public utilities and communications.” The question was how long Hodge and his staff would have to rely on the Japanese. Benninghoff pointed out a possible way out: “Seoul, and perhaps southern Korea as a whole, is at present politically divided into two distinct political groups. On the one hand there is the so-called democratic or conservative group, which numbers among its members many of the professional and educational leaders who were educated in the United States or in American missionary institutions in Korea. In their aims and policies they demonstrate a desire to follow the western democracies.” On the other hand, “there is the radical or communist group. This apparently is composed of several smaller groups ranging in thought from left of center to radical. The avowed communist group is the most vocal and seems to be supplying the leadership.” Benninghoff believed that the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) would be able to work with the so-called conservative group. He also optimistically concluded, “Although many of them have served with the Japanese, that stigma ought eventually to disappear.”48

Early in the occupation, USAMGIK had attempted to be neutral in its treatment of the various and often hastily organized Korean political groups. But this policy proved to be increasingly difficult. For practical purposes, the Americans needed Koreans who spoke English, but “it so happened that these persons and their friends came largely from the moneyed classes because English had been a luxury among Koreans.” They were therefore part of the privileged conservatives far removed from the masses.49 The Americans also needed Koreans who supported the occupation’s aims, which meant that these Koreans required American support to remain in power. The “radical” group identified by Benninghoff did not fit either of these categories.

Ironically, it was the Japanese who were largely responsible for the viability of the so-called “radical” group. On August 14, Abe met with Yŏ Un-hyŏng, a moderate leftist who was rumored to be a member of a Korean communist group in Shanghai. Abe said that the Japanese were planning to surrender the following day, and asked Yŏ to organize a group to help maintain order. Yŏ agreed. Within a few weeks, the organization that was meant to keep the Koreans in line during the transition period until the arrival of the Americans had transformed into a self-declared and de facto Korean government. Two days before the Americans’ arrival, Yŏ declared that his newly established organization was not only a political party but also the government of the Korean People’s Republic (KPR). The KPR group attracted many populist and left-leaning nationalists whose paramount concern was not ideology, but the establishment of an independent Korean state.50

On the morning of September 8, three leading members of the KPR group, including Yŏ, went to meet Hodge. Yŏ viewed the American occupation command as a transitional authority between the Japanese colonial government and the newly established KPR. The members had come to offer their services as a liaison between the American military command and the Korean people. They were also emphatic about removing the Japanese from Korea as quickly as possible. Hodge, ironically, refused to meet them because the KPR group was formed with Japanese support. He considered it “unwise to give even the slightest possible appearance of favoring any political group.”51 In a double irony, it also became apparent that the allegedly “pro-Japanese” KPR was not supported by the Japanese, who considered Yŏ to be a “political opportunist with communist leanings.” The Americans were warned that the KPR was “better organized and more vocal” than any other political group in Korea, and that “the nature and the extent of actual communist (Soviet Russia) infiltration cannot be stated with certainty, but may be considerable.”52

More alarming was the KPR’s unwillingness to cooperate with USAMGIK. By mid-September, the KPR began organizing numerous subsidiary groups throughout the country. The group released political prisoners, assumed responsibility for public safety, and organized food distributions. In addition, the KPR called for a national election as early as March 1946. Realizing that the authority of the occupation was being undermined by the KPR, Maj. Gen. Archibald Arnold, the military governor of Seoul, issued a strongly worded statement against the organization for “confusing and misleading” the Korean people. He declared that “there is only one Government in Korea south of the 38 degrees north latitude”; it is the government “created in accordance with the proclamations of General MacArthur, the General Orders of Lieutenant General Hodge and the Civil Administration order of the Military Governor.” Arnold also mocked the KPR’s “self-appointed ‘officials,’ ‘police,’ groups, big (or little) conferences,” which he said were “entirely without any authority, power or reality,” and warned the KPR leaders that the “puppet show” must end. “Let us have no more of this,” he declared. “For any man or group to call an election as proposed is the most serious interference with the Military Government, an act of open opposition to the Military Government and the lawful authority of the Government of Korea under the Military Government.”53

Arnold’s proclamation appalled the KPR leaders. While his statement was meant to show who was in charge, its demeaning tone and condescending language resulted in further alienating the KPR and ordinary Koreans from the Americans. In response, the KPR published The Traitors and the Patriots. The pamphlet began with an exposure of allegedly pro-Japanese officials who were advising USAMGIK. It attacked the notion that USAMGIK was the only legitimate government south of the 38th parallel. The KPR, the pamphlet asserted, “was the duly constituted organ of the people,” and Arnold’s statement was condemned as an “insult to the Korean people.”54

By mid-October 1945, Hodge understood that the KPR could have no future role under the American occupation. USAMGIK gave its support to the Korean Democratic Party (KDP), the group of conservatives first identified by Benninghoff. What the Americans needed most at this time was bilingual, educated, and above all, cooperative allies to deal with rising discontent and revolutionary sentiments. Hodge was less worried about the KPR’s leftist ideology than its deliberate attempts to subvert his authority. A crackdown on the KPR soon ensued. His willingness to accept leftist organizations as long as they did not challenge USAMGIK’s authority also reflected MacArthur’s tolerance of leftists and communists in Japan at the time.

Hodge miscalculated in thinking that disbanding the KPR would end the challenges to USAMGIK’s authority. Many Koreans were by now deeply disillusioned by the failed expectations of liberation. Especially critical was land reform and rice supply. USAMGIK seized Japanese-owned land but did not turn it over to Korean farmers. Theoretically, former Japanese land was to be held in escrow for redistribution as part of a land reform plan, but lack of planning led to rumors that the land would be given to wealthy landlords, those who had collaborated with the Japanese, and supporters of the American occupation. Many Koreans believed that the Americans were reestablishing the same system of land ownership and political dictatorship that had prevailed under the Japanese. Furthermore, in the fall of 1945, USAMGIK abolished the price controls on rice. The bumper crop in 1945 led many to expect that for the first time in decades, Koreans would have an ample supply of rice since no rice would be sent to Japan, as had been the practice during the colonial period. But just the opposite result occurred. With price controls gone, speculators bought up the rice they could find, driving up the price. Greedy farmers withheld rice in anticipation of greater profits. USAMGIK did little to stop the hoarding, while hungry Koreans demanded that price ceilings be reinstituted. In March 1946, the Americans were forced to issue directives for rationing, but these controls only reminded Korean farmers of the former Japanese system. To make matters worse, the average Korean received only half the amount of rice he or she had received under the Japanese.55 “As a result of its handling of the rice problem, the Koreans arrived at a complete loss of faith in the Military Government,” lamented an attorney who served in Korea during this period.56

General Hodge broadcasting to the United States about the conditions of American troops in Korea, April 18, 1948. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

The Americans also had a problem the Soviets did not: the repatriation of several hundred thousand Japanese soldiers and civilians.57 In October alone, more than eighty-eight thousand were evacuated, creating enormous administrative and logistical pressures on the relatively small American force. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Korean refugees from the Soviet zone and Manchuria added to the south’s economic plight. “The refugee crisis,” stated an embassy report, “is making living conditions increasingly hard. Three-quarters of the population of Korea is now in our hands and the Koreans are looking to us for a solution to their problem.”58 Inflation, black markets, scarcity of consumer goods, and an unbalanced wage scale added to the economic and political confusion in the American zone.

The rice shortage in Pusan came to a head on the evening of July 6, 1946, when a mob of hungry people attempted to break into a rice distribution center. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

The morale of the Americans was a problem as well. Charles Donnelly, an economic advisor to the U.S. Army Forces in Korea (USAFIK was the overall military command in Korea and oversaw USAMGIK), noted that “the shortage of typewriters, stencils, and chairs is scandalous.”59 Empty shelves in the post exchange glumly revealed the reality of being at the end of a long supply line from the United States. One reporter counted the following items for sale in early December: “ten cartons of cigarette, five bars of candy, six toothbrushes, several packages of razor blades, and a few pads of writing paper, all for 500 soldiers.” Americans, who “just a few weeks ago were selling cigarettes to the Koreans, are now buying them back at a high cost … grumbling soldiers and officers are complaining that folks at home don’t seem to care, now that the war is over, whether we are getting supplies or not.”60 Another chronic problem was theft. “Thievery here is rampant,” Donnelly complained. “My felt hat was stolen from my office. Miss Carol’s handbag with sixty dollars in it was taken from her desk while she was in the restroom. Simon lost his hat and top coat. A resident in the Bizenya [a hotel] awoke to find that his room was literally stripped of everything except the bed in which he was sleeping.” Relations between the Americans and the Koreans were increasingly strained. The Koreans resented the occupation while the Americans increasingly disliked the Koreans because they acted “like difficult spoiled children.” “The Koreans are unwilling to take the time to develop political and economic know-how,” wrote Donnelly. “All they want is for Americans to get out of their country so that they can run it by themselves.”61 By the end of 1945, the Americans were struggling to gain control over an increasingly chaotic and demoralizing situation. Something had to be done.