The opening shots of the attack in the predawn hours of Sunday, June 25, 1950, surprised few, and yet all were caught unprepared. Localized skirmishes and even major actions along the parallel had occurred with regularity over the previous year, and nothing in the way the North Korean attack began gave any indication that it was different this time. Almost nightly, the North Koreans infiltrated patrols to probe, ambush, or take prisoners. The South Koreans retaliated with their own patrols. These actions sometimes involved hundreds of men. Not infrequently, artillery duels were waged. A year earlier, North Korean shelling near Kaesŏng, located just south of the parallel, was of such ferocity that the American Methodist Mission there was forced to stay in a shelter for three days.1 Border skirmishes had continued unabated since January, but in May, border incidents suddenly dropped off sharply, making Capt. Joseph Darrigo of KMAG suspect that something was afoot. North Korean farmers were evacuated from the border zone. Captain Darrigo reported his concerns to his superior, Lt. Col. Lloyd H. Rockwell, but it was lost in the cacophony of similar warnings that had become almost routine in Seoul and Washington.2

The five hundred U.S. military advisors of KMAG were under the leadership of Brig. Gen. William Roberts, who was nearing his mandatory retirement in July. KMAG’s mission was to train and build functioning ROK security forces, especially the army. It was a daunting challenge requiring patience and skill. But Roberts was an optimist. The ROK Army had, after all, been battle-tested in the Yŏsu-Such’ŏn uprisings and in the numerous clashes along the border. It had proved its loyalty and its mettle. Roberts reported to Washington that the ROK Army could meet any test the North Korean army might impose on it.3 The optimistic assessments were also voiced by the ambassador to South Korea, John Muccio, who confirmed that progress in military training had been “heartening,” and the ROK Army “had kept pace” with the North Koreans.4 The official view from Washington was summed up by Republican Senator H. Alexander Smith (New Jersey), a recent guest of Ambassador Muccio, who reported that the ROK forces were “thoroughly capable of taking care of South Korea in any possible conflict with the North.”5

President Syngman Rhee disagreed. He interpreted the stream of positive assessments of the fledgling army, which had no tanks, no heavy artillery, and no fighter aircraft, as a deceptive ploy to deny him military aid and equipment. He complained to Muccio and Roberts that the ROK Army was woefully underequipped to repel a North Korean attack. In Washington, however, denial of Rhee’s repeated requests for more arms was thought to be prudent and justified. There was legitimate concern that the difficult and fiercely patriotic Rhee might start a war of reunification on his own if he were given the tanks, artillery, and aircraft he demanded. A week before the outbreak of war, Muccio wrote to Ache-son, “The Korean Army has made enormous progress during the past year. The systems and institutions set up through the instrumentality of KMAG are now such that reductions in advisory personnel can well be made,” and he recommended a 50 percent reduction by the end of 1950.6 More important was a definitive shift in reducing South Korea’s strategic value to the United States. Democratic Senator Tom Connally (Texas), chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, told a reporter that “I am afraid it [the United States abandoning South Korea] is going to be seriously considered because I’m afraid it is going to happen, whether we want it to or not.”7 The praises heaped on the ROK military provided political cover for drawing down American commitments. Rhee had reasons to be concerned.

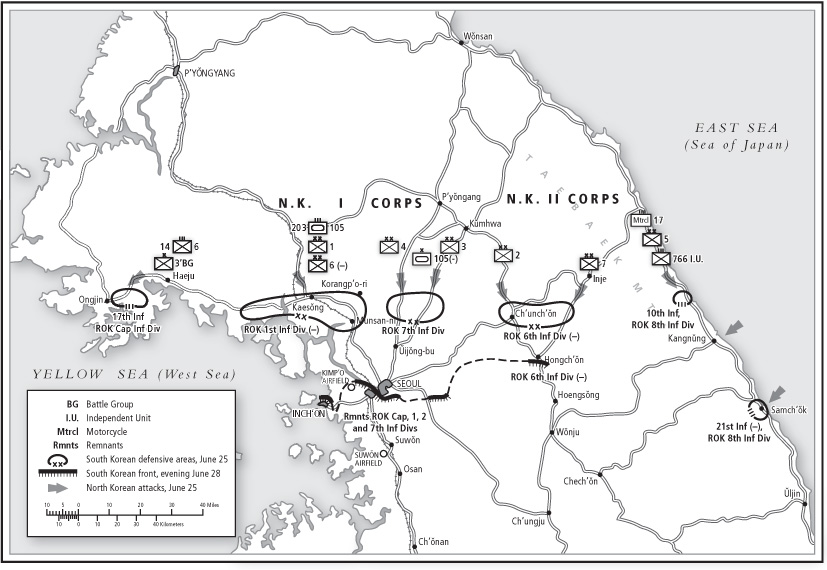

North Korean Invasion, June 25–28, 1950. (MAP ADAPTED FROM ROY B. APPLEMAN, SOUTH TO THE NAKTONG, NORTH TO THE YALU [U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, 1960])

Captain Darrigo was the only American officer at the 38th parallel on the morning of June 25. He was the KMAG advisor to a regiment of the ROK First Division, and he lived in Kaesŏng. Darrigo jumped out of bed when he heard artillery shells land nearby, ran to his jeep, and sped away, reaching the division’s headquarters in Munsan, about twenty miles to the south, to sound the alarm. Unfortunately, the very capable division commander, Col. Paek Sŏn-yŏp, perhaps the best officer in the ROK Army who later became its first four-star general, was absent. Lieutenant Colonel Rockwell, chief KMAG advisor to the ROK First Division, was also absent. He had gone to Seoul for the weekend to visit family and friends. By the time they were notified later that morning and hurriedly made their way back, Kaesŏng had fallen and NKPA tanks were rolling toward Seoul.

The NKPA conducted six sequenced thrusts across the 38th parallel, beginning in the Ongjin Peninsula on the west and then rolling eastward. KMAG advisors with the ROK 17th Regiment on Ongjin had also been jolted from their beds by artillery. Without heavy weapons, the regiment had little chance. At first, many ROK soldiers fought bravely. “Acting without orders from their officers,” recalled Paek, “a number of them broke into suicide teams and charged the T-34s clutching explosives and grenades. They clambered up onto the monsters before touching off the charges.”8 But the futility of the “human bomb” attacks soon led to “T-34 fear,” and the troops began to run away. “The symptoms of the disease were straightforward,” Paek later wrote. “As soon as the men even heard the word ‘tank’ they fell into a state of terror.”9

When news of the North Korean invasion reached Washington in the early evening of Saturday, June 24, many officials, including Truman and Acheson, were away for the weekend. Truman was at his home in Independence, Missouri. Acheson called from his country house in Maryland to inform the president of the news. He also told Truman that he had requested an emergency session of the UN Security Council.10 While Truman returned to Washington, the UN Security Council met and unanimously adopted an American resolution calling for the immediate cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of North Korean troops. There was no Soviet vote, and hence no veto, because the Soviet representative had walked out earlier that year to protest the UN’s refusal to seat the PRC in the council instead of Taiwan. Truman gathered his principal advisors for a crisis meeting. All agreed that the Soviet Union was involved. Acheson recommended that MacArthur be instructed to airdrop supplies, food, ammunition, and weapons to strengthen the South Korean forces. No direct U.S. military involvement was discussed, as it was still widely believed that the ROK Army was capable of handling the NKPA. This belief was reinforced by the first of many cables from Ambassador Muccio: “The Korean defense forces are taking up prepared positions to resist northern aggression. There is no reason for alarm.”11

Muccio’s reports became more ominous the following day: “I earnestly appeal to Department to back up to such extent as may be necessary KMAG’s appeal for additional ammunition. Without early receipt of such ammunition and assuming hostilities continue at present level, is feared most stocks in Korean hands will be exhausted within ten days time.”12 Faced with bleaker reports about the situation on the front, and with rumors running wild that the NKPA was about to take Seoul, Muccio ordered the evacuation of American civilians. On the morning of Tuesday, June 27, nearly seven hundred American women and children boarded a Norwegian ship at Inch’ŏn and sailed for Japan. More Americans were evacuated the following day, and Muccio went to Suwŏn, twenty-five miles south of Seoul. Rhee and the ROK government had departed earlier that morning and were on their way farther south to the city of Taegu. Ordinary Koreans were on their own. Some stayed, but many left, becoming faceless actors in innumerable tragedies on the refugee trail. In just two days, Seoul was in chaos and its residents in full flight.

Not everyone was eager to leave the city, however. Four American journalists, Keyes Beech of the Chicago Daily News, Frank Gibney of Time, Marguerite Higgins of the New York Herald Tribune, and Burton Crane of the New York Times, arrived on one of the last evacuation planes from Tokyo on June 27 to cover the fall of Seoul.13 They were greeted at ROK Army headquarters by Col. W. H. Sterling Wright, KMAG’s acting chief, and a skeleton crew of KMAG officers. KMAG’s chief Brig. Gen. Roberts had departed just days before to retire and his replacement had not yet arrived. Despite the bleak situation, Wright was hopeful. He and others had been bolstered by MacArthur’s message earlier that day that “momentous events are in the making.”14 It was after midnight when the group finally decided to turn in. Colonel Wright suggested that Marguerite Higgins, together with a group of other KMAG officers, accompany him to his quarters in the KMAG housing area. Meanwhile, Beech, Gibney, and Crane went with Maj. Walter Greenwood, who offered the men a place on the sofa and floor to sleep. But no sooner had they closed their eyes when they were awakened by the phone. Beech heard Green shout, “They are in the city! Head for Suwŏn!” It was raining hard that night as Gibney, Beech, and Crane jumped into their jeep. “The whole city was on the move,” recalled Beech. “It was toward the Han River Bridge.”

The pitiful human mass, wet and trudging through the dark, created an eery scene. Caught in the streaming mobs of people, oxcarts, trucks, and bicycles, the three reporters saw Capt. James H. Hausman ahead of them as they approached the bridge. Suddenly everything came to a halt. “We sat in the jeep waiting,” Beech recalled. “Then it seemed that the whole world exploded in front of us. I remember a burst of orange flame; silhouetted against the flame was a truckload of Korean soldiers. The truck lifted into the air. I felt our own jeep in motion, backwards.”15 Crane and Gibney were wounded by flying glass and bled from their heads, but they were conscious and able to walk. Beech noticed the truckload of soldiers whose vehicle had shielded them from the blast. All of the soldiers were dead, their bodies strewn haphazardly in heaps on the ground. And so were hundreds of other innocent people who had died in the explosion or who had simply drowned in the dark river waters below. Someone had blown up the Han River Bridge with people still on it.

Hausman’s group had been luckier. They were safely across the river when the bridge blew. “It was a tremendous explosion,” he recalled, “Our jeep actually left the road, vertically.”16 Meanwhile, Wright and Higgins, who had not yet crossed the bridge, were unharmed although they now found themselves, like Gibney, Crane, and Beech, trapped on the wrong side of the Han River. Fortunately they were able to make it safely across on makeshift rafts. The KMAG party, including the four American journalists, had come through the ordeal miraculously, without loss of life.

The premature destruction of the bridge was not only a humanitarian disaster but a military one as well. Seoul was still in ROK hands at the time, and trapped on the northern side of the Han River were over thirty thousand ROK soldiers. Colonel Paek, whose men had fought heroically to hold back the attack, was devastated: “I cried tears of blood on that day. I saw no way to rescue the men of the proud ROK 1st Division, scattered as they were over miles of threatening terrain.”17 Brigadier General Yu Chae-hŭng, commander of the ROK Seventh Division, led just over one thousand men to safety. The other two ROK divisions that were still relatively intact, the ROK Sixth Division in Ch’unch’ŏn to the east and the Eighth at Samch’ŏk on the East Sea, were now isolated and utterly helpless.

On June 28, three days after the attack, the ROK Army could account for only twenty-two thousand men of the nearly hundred thousand that had made up its rolls on the twenty-fifth. Most of its heavy weapons, transport, and supplies were lost. General Roberts’s “best doggone shooting army outside of the United States” was not just defeated, it was destroyed.18

MacArthur’s survey team, sent to assess the situation and led by Brig. Gen. John Church, landed in Suwŏn on June 27, just hours before the fall of Seoul. Church was shocked by the utter chaos. Hausman, who had just arrived in Suwŏn, related the horrific story of the Han River bridge explosion and the ROK Army’s dire predicament. Church notified Tokyo that “it will be necessary to employ American ground forces” to reestablish ROK positions at the 38th parallel and to recapture Seoul.19 That evening, MacArthur radioed Church that a senior officer would be arriving the next morning. That senior officer turned out to be MacArthur himself. A distraught Rhee greeted MacArthur. Church and Wright briefed them on the deteriorating situation. Returning to Tokyo that evening, MacArthur cabled Washington: “The only assurance for holding the present line and the ability to regain later the lost ground is through the introduction of United States ground combat forces into the Korean battle area. Unless provision is made for the full utilization of the Army-Navy air team in this shattered area, our mission will at best be needlessly costly in life, money and prestige. At worst, it might even be doomed.”20 But Truman had already decided to intervene. Later, he said that committing American troops to combat in Korea was the most difficult decision of his presidency, more so than the decision to use the atomic bomb against Japan in 1945. He did not want to get into a war, but he thought that failure to act in Korea could lead to another world war, this time with the Soviet Union.

On June 27, congressional leaders, the secretary of state, the secretary of defense, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) joined Truman for a meeting. He informed them that that morning he had authorized the use of air and sea forces. The congressional leaders approved that the crisis be managed on the basis of presidential authority alone, without calling on Congress for a declaration of war. That evening, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 83 authorizing the use of force to halt North Korean aggression, testing for the first time the UN principle of collective security. In the days leading to the UN resolution, the American people’s anxiety and doubt over what to do about Russia’s “testing” of America’s resolve in Korea had suddenly given way to a new clarity and sense of purpose. Three days later, on June 30, Truman authorized the deployment of American ground forces.

The response of the American people, the media, and Congress was overwhelmingly positive. The press unanimously praised Truman for his “decisiveness” and his “bold and courageous decision.” The Christian Science Monitor’s Washington Bureau chief, Joseph Harsh, gushed, “Never before have I felt such a sense of relief and unity pass through the city.”21 Truman had drawn the line, and the American public firmly backed him. Yet, there was still confusion concerning exactly what the crisis was all about. At a June 29 press conference, Truman was asked whether the United States was at war. “We are not at war,” Truman replied. A reporter asked, “Would it be correct … to call this a police action under the United Nations?” “Yes,” replied Truman, “that is exactly what it amounts to.”22 Calling Korea a “police action” would later haunt Truman when the bloody and brutal reality of a full-blown war became apparent. Throughout the hot months of July and August 1950, American soldiers were stunned and humiliated as they were repeatedly thrown back by the North Korean “bandits.” For the time being, however, Truman’s euphemism served to downplay the seriousness of the crisis and provided the illusion that the “police action” would be a relatively quick and simple affair.23

Less than six days after the North Korean attack, American soldiers were committed to the fighting. The former Japanese colony that few had ever heard of and had been on the periphery of America’s post-war interests suddenly became the epicenter of America’s first armed confrontation against communism. Truman had drawn the line in Korea between freedom and slavery. Haphazardly and fatefully, Korea’s localized civil war morphed into a war between the centers of power in the post–World War II order.

The first American troops arrived in Korea confident that the North Koreans could be stopped quickly. Virtually nothing was known about the enemy, but everyone thought that once the North Koreans saw that they were fighting Americans, they would retreat in panic. Overconfidence and arrogance ruled the day. “We thought they’d back off as soon as they saw American uniforms,” Lieutenant Philip Day recalled. Lieutenant John Doody echoed the sentiment: “I regarded the episode as an adventure that would probably last only a few days.”24 Their first encounter with the NKPA abruptly exploded their illusions. More important, the confrontation between the world’s most powerful nation and a nation of “bandits” was a brutal wake-up call to Washington, for it showed just how much American military readiness had deteriorated. America’s precipitous demobilization and slashed defense budgets after World War II, the peace dividend, and the “soft” occupation in Japan exacted an unforgiving outcome in the violence of combat. It was glaringly apparent that despite its vaunted nuclear supremacy, America was unprepared to fight a conventional war.

MacArthur selected the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division as the first unit to deploy. The division and its commanding general, Maj. Gen. William Dean, seemed well suited for the job. Dean was the only one of the four division commanders in the Eighth U.S. Army, the American occupation force in Japan, to have commanded troops in combat. He had also served as commanding general of the Seventh Infantry Division and as military governor of South Korea under Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge from 1947 to 1948. Dean took command of the Twenty-Fourth Division after the dissolution of USAMGIK following the elections in May 1948. MacArthur instructed Dean to send a battalion task force, as quickly as possible, to be followed by the remainder of the division. Dean chose the 1st Battalion of the 21st Infantry Regiment commanded by Lt. Col. Charles Smith as the core of the task force. Smith had fought in the Pacific in World War II and was considered the most experienced and competent of the battalion commanders in the division. But the unit was only at two-thirds strength and most of the soldiers had no combat experience, having joined after World War II. The unit also lacked training, owing to the “soft” occupation duty in Japan. The equipment was in poor shape, and antitank weapons were inadequate against the tanks of the NKPA. Task Force (TF) Smith was the best that MacArthur could send, a unit of ill-trained, undermanned, underequipped, and underexperienced men.25 Dean’s instructions to Smith were simple: “Contact Brig. Gen. John Church and if you can’t locate him, go to Taejŏn and beyond if you can … Good luck to you and God bless you and your men.”26

Brigadier General Church greeted TF Smith at Taejŏn on the morning of July 2. Brimming with confidence, Church assured Lieutenant Colonel Smith that all that was required to stop the NKPA was a few Americans who would not run from tanks. Smith was ordered to block the enemy north of the village of Osan. The NKPA’s primary avenue of attack was along the main road from Seoul, which ran through Osan and farther south through Taejŏn and Taegu to Pusan. It was the only avenue of attack from the Chinese border to the southern coast that was free from the mountains dominating most of the peninsula. To this day, this corridor is the key line of communication and transportation and therefore the backbone of South Korea’s bustling economy. It was also the traditional invasion path through the peninsula whether coming from the north or from the south. The Mongols in the thirteenth century and the Manchus in the seventeenth century followed it going south; the Japanese followed it north during their invasion in the sixteenth century. The NKPA, in other words, was using a well-worn path. As TF Smith deployed north of Osan, the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division’s 34th Infantry Regiment, led by Col. Jay Lovless, arrived in P’yŏngtaek south of Osan. Dean deployed the regiment around P’yŏngtaek to block any enemy that got through TF Smith.

Smith and his men caught sight of the North Korean soldiers on the morning of July 5. Over thirty tanks rolled toward their positions. The Americans fired recoilless rifles and bazookas at point-blank range, but to their surprise, even direct hits had no effect. The artillery battery attached to TF Smith destroyed four of the tanks, but still nearly thirty had gotten through and headed south toward the 34th Infantry Regiment digging in at P’yŏngtaek. By early afternoon, Smith ordered a withdrawal. Soon thereafter, “things slowly began to go to pieces,” Lt. Philip Day recalled. “All crew served weapons were abandoned, as well as all the dead and some 30 wounded. Confusion rapidly became rampant.”27 A quarter of the unit, 150 men, was lost at Osan.28

Reports that TF Smith was overrun reached Lovless the next morning. Fearful that the understrength battalion at P’yŏngtaek might not be able to hold, Lovless ordered it to fall back to Ch’ŏnan, about eight miles farther south. Meanwhile, a battalion at Ansŏng to the east fell apart. Dean was furious that P’yŏngtaek was abandoned without a fight, and he ordered Lovless to go back, but it was too late because P’yŏngtaek had already been taken by the NKPA. By this time, Ch’ŏnan’s defenses rapidly fell apart, and the hasty withdrawal from P’yŏngtaek and Ansŏng now turned into a frantic flight. The men abandoned equipment, weapons, and comrades who had been killed or wounded. “I was thoroughly disgusted with this exhibition,” recalled John Dunn. “It was more than a lack of aggressiveness and initiative, it bordered on cowardice.”29 Dunn, who was taken prisoner at Ch’ŏnan, spent the rest of the war in a POW camp. It took just a few days for the cocky and confident American soldiers to become a disoriented mob of terrified men.

As bewildered American and ROK troops were flung back, MacArthur decided to commit the whole of the Eighth U.S. Army. Lieutenant General Walton “Johnnie” Walker, its commander, was known as a “GI’s general.” A modest and unpretentious man who “smiled infrequently and rarely voiced a remark worthy of being remembered,” Walker made a personal assessment of the situation by visiting Dean at Taejŏn in early July.30 His assessment was crucial in MacArthur’s decision to use all of the Eighth Army. Walker’s operational control included the remnants of the ROK Army, conceded by President Rhee on July 14.31 The unified U.S.-ROK forces gave hope of establishing a coherent defense.

Delaying actions, 34th Infantry Regiment, July 5–8, 1950. (MAP ADAPTED FROM ROY B. APPLE-MAN, SOUTH TO THE NAKTONG, NORTH TO THE YALU [U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, 1961])

Much has been made of the ROK Army’s poor performance, but this ignores the heroic efforts made to successfully rebuild the ROK Army on the run.32 The South Koreans were able, against great odds, to piece their shattered forces back together while fighting a delaying action without collapsing, despite their inferiority in men, arms, equipment, and training. “We started greatly under-strength and bereft of heavy weapons and equipment and were obliged to reorganize, replenish and even re-arm while keeping ahead of a pursuing enemy,” recalled Paek Sŏn-yŏp. “In what I regard as one of the minor miracles of the war, some four or five thousand of the men we lost crossing the Han rejoined the division during our withdrawal to the Naktong [River].”33 ROK forces reached their prewar strength by the end of August.34 Kim Il Sung later acknowledged that “our greatest mistake was failing to encircle and completely annihilate the enemy, and giving them enough time to reorganize and reinforce their units while withdrawing.”35

Walker’s immediate task was to delay the enemy advance. In the west, location of the NKPA’s main effort, Walker established a defensive line along the south bank of the Kŭm River. In the east, Walker used the mountains and the narrow coastal corridor to delay the North Korean advance. The purpose of the delay was to buy time for reinforcements, not only from the United States, but also from over a dozen other UN nations, to arrive and set the conditions for a counteroffensive. The Kŭm River was the first defensible river line south of the Han along the path of North Korea’s advance. Less than fifteen miles beyond it was Taejŏn, the first major city after Seoul along the invasion route. Walker wanted Dean’s Twenty-Fourth Division to hold the Kŭm River line to protect Taejŏn, a key nexus of road and rail networks. But Dean’s forces could not hold, and the North Koreans easily penetrated the Kŭm River line and then began assaulting Taejŏn on July 20. Whereas Dean’s tactical sense called for withdrawing from Taejŏn as it was being surrounded, he was ordered to hold on to gain time for reinforcements to arrive from Pusan. It was a fateful delay. Dean became trapped as NKPA forces closed in from all sides. Escaping the city on foot, he survived in the mountains for thirty-six days before being captured, and spent the rest of the war as a POW. Dean was the highest-ranking POW, and in January 1951, Truman, not knowing whether he was alive, awarded him the Medal of Honor.

By the end of July, the Twenty-Fourth Division was in very bad shape. It had lost more than half of its men.36 It had been a desperate, agonizing, and bitter month. Many soldiers felt that their leaders, from Truman on down, had failed them. They had been told that their sojourn in Korea would be an easy affair, a mere “break” from the boredom of the occupation in Japan. Moreover, the difficulty of identifying friend from foe, because some NKPA troops infiltrated UN lines by disguising themselves in the same white-cotton clothes that refugees wore, led American troops to commit appalling deeds, including shooting at women and children, because they did not know what else to do.

Near the village of Nogŭn-ri, about a hundred miles southeast of Seoul, several hundred refugees were killed in late July by soldiers of the 7th Cavalry Regiment from the First Cavalry Division and by American aircraft. The American soldiers, who believed North Korean soldiers were hiding among the villagers, had told the villagers to gather by the railroad tracks. There are contradictory accounts of what happened next. One Korean witness recalled spotting an American plane that suddenly swooped down and strafed the area. An American soldier recalled receiving fire from the refugee group.37 Whatever triggered the mayhem, the terrified villagers ended up in a nearby tunnel, where they sought cover and ended up trapped.38 Yang Hae-chan, nine at the time, recalled that they were “fired upon by American soldiers, bullets rained down on the crowd.”39 Another eyewitness said they were “packed tightly inside with little or no room to move,” and recalled having to “drink bloody water from the stream that flowed through one of the tunnels.” The killing lasted several days, and “dead bodies were piled up on the tunnel entrance” to protect those inside from the oncoming fire. Two hundred and forty-eight people, including many women and children, are alleged to have been killed in the incident.40

Early August brought more despair but also new hope. American and ROK forces set up a defense line behind the Naktong River. It was a thinly held front and the last line of defense. On the map, the Pusan perimeter looked like a tiny toehold at the southeastern corner of the peninsula. Walker dramatically declared, “There will be no Dunkirk, there will be no Bataan … We must fight until the end … I want everybody to understand that we are going to hold this line. We are going to win.”41 The soldiers were exhausted, bitter, and dispirited. The monsoon season had just ended, but it was abnormally hot and dry. Lack of water forced the soldiers to drink from paddies and ditches, causing severe cases of dysentery. Yet, despite the exhaustion, the heat, and the sickness, Walker’s line held.

One key to this success was the delaying action of the ROK Sixth Division, which had put up a tenacious fight in Ch’unch’ŏn thirty miles east of Seoul against overwhelming odds.42 A KMAG advisor recollected that the Sixth Division was driven from the city but “counterattacked and recaptured Ch’unch’ŏn and then held it for five days until ordered to withdraw because of failure along the rest of the front.”43 Shtykov reported on June 26 to Gen. Matveyev Zakharov, head of a special mission from the Soviet General Staff to oversee the operations, that “the invasion ran into trouble from the beginning especially because the Soviet plan did not take into account the severe terrain that slowed down mechanized units and especially the unexpectedly courageous defense of the ROK 6th Division at Ch’unch’ŏn.”44 The ROK Sixth Division’s delaying actions threw off the NKPA’s timeline and probably bought time for the establishment of the Pusan perimeter and the arrival of UN reinforcements.45

Shtykov was worried. He wrote to General Zakharov that NKPA units were operating on an ad hoc basis without direction from senior staff. The quality of staff work was poor, “[the command staff] does not have battle experience,” he complained, and “after the withdrawal of Soviet military advisers they organized the battle command poorly, they use artillery and tanks in battle badly and lose communications.”46 On June 28, Shtykov reported to Stalin that without more Soviet advisors on the ground, “it would be difficult for the NKPA to conduct smooth operations.”47 On July 8, Shtykov cabled Stalin to convey Kim Il Sung’s personal appeal for more Soviet advisors for frontline units: “Being confident of your desire to help the Korean people rid themselves of the American imperialists,” Kim pleaded, “I am obliged to appeal to you with a request to allow the use of 25–35 Soviet military advisers in the staff of the Front of the Korean Army and the staffs of the 2nd Army Group, since the national military cadres have not yet sufficiently mastered the art of commanding modern troops.”48 Kim confided to Shtykov that without the advisors, “the invasion would fail.” Shtykov wrote to Stalin “that he had never seen Kim Il Sung so dejected and hopeless.”49 Stalin acquiesced. That Stalin would have allowed Soviet advisors to serve in the front lines and risk a direct confrontation with Americans revealed how critical the situation had become.50 By mid-July, the NKPA had largely lost its momentum.

The next Eighth Army unit to arrive was the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division, which included the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment. Following the Twenty-Fifth was the First Cavalry Division in mid-July and the 5th Regimental Combat Team from Hawaii, which arrived on July 25. The Second Infantry Division followed in early August and then a provisional U.S. Marine brigade. With these reinforcements, a defensive line was established along the Naktong River in southeastern Korea. The Eighth Army was responsible for the seventy-mile western flank of the Pusan perimeter, while the ROK Army was responsible for the fifty-five miles of the front on the northern boundary. With overextended supply lines and increasing UN strength, North Korea estimated that it had about a month at most to break the Pusan line and bring the war to a conclusion in its favor. Throughout August and early September, the NKPA maintained unrelenting pressure, but the perimeter held.

As the situation in Korea stabilized, Truman sent W. Averell Harriman, a senior White House advisor, to Japan. Truman had been disturbed by MacArthur’s highly publicized trip at the end of July to Taiwan, where he had met Chiang Kai-shek and publicly praised the generalissimo’s “indomitable determination to resist communist domination.”51 Secretary of State Acheson was upset, but he put MacArthur’s trip down to politics. “Before 1950 General MacArthur had neither shown nor expressed any interest in Formosa,” wrote Acheson. “But the General was not deaf to political reports coming to him from the United States, particularly those emanating from the Republican right wing, which found our Far Eastern policy repulsive and occasionally mentioned the General as the charismatic leader who might occasionally end the obnoxious Democratic hold on the White House.”52 It was well known that MacArthur had looked favorably on Chiang’s offer of Nationalist troops for Korea, but Truman rejected the offer for fear of drawing China into the war. Truman told Harriman to tell MacArthur to stay clear of Chiang Kai-shek and to find out MacArthur’s future plans for Korea.53 Harriman returned with an encouraging report. Concerning Chiang Kai-shek, MacArthur would do as the president ordered. For the war, Harriman reported on MacArthur’s plan for victory with a bold amphibious landing at Inch’ŏn, behind enemy lines, to surround and destroy the North Korean forces.

MacArthur’s audacious plan carried great risks. The greatest were Inch’ŏn’s tremendous tides of thirty feet or more and the lack of suitable landing beaches. The landing could take place only at high tide, which lasted just two hours. General Omar Bradley, chairman of the JCS, thought it was the riskiest plan he had ever seen. General Joseph “Lightning Joe” Lawton Collins, army chief of staff, thought the plan should be modified by making the landing site at Kŭnsan instead of at Inch’ŏn. Kŭnsan was located 130 miles south of Inch’ŏn. Geographically, it was more hospitable and accommodated more easily the amphibious landing MacArthur proposed. But it was precisely the “impracticalities” of the operation that could ensure Inch’ŏn’s success, MacArthur argued, “for the enemy commander will reason that no one would be so brash as to make such an attempt.”54 The Joint Chiefs were not convinced. Secretary of the Army Frank Pace Jr. noted that “the almost universal feeling of the Joint Chiefs was that General MacArthur’s move was very risky and had very little chance of success.”55 Whether MacArthur was angered by the reluctance of the Joint Chiefs or simply frustrated by the events in Korea, he almost lost all support for the Inch’ŏn plan when he challenged Truman’s Far East policy in late August. In response to an invitation by the Veterans of Foreign Wars to send a message to its annual convention, MacArthur chose to address the thorny issue of Taiwan. As he did during his trip to the island a few weeks earlier, MacArthur argued for Taiwan’s strategic value and attacked those who opposed supporting Chiang Kai-shek. “Nothing could be more fallacious than the threadbare argument by those who advocate appeasement and defeatism in the Pacific that if we defend Formosa, we alienate continental Asia,” he declared. Drawing on his claim of intimate knowledge of the “Oriental mind,” he concluded, “Those who speak thus do not understand the Orient. They do not grant that it is in the pattern of Oriental psychology to respect and follow aggressive, resolute and dynamic leadership, to quickly turn on a leadership characterized by timidity or vacillation.”56 Widely covered by the media, MacArthur’s message represented exactly the kind of dabbling in politics that Truman had warned MacArthur against. Truman, however, appeared swayed in favor of the Inch’ŏn plan by a strong memorandum of support from Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, the U.S. Army’s deputy chief of staff for operations and administration and a World War II hero, who had gone to Japan with Harriman.57

MacArthur chose his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Edward Almond, to command the landing force, X Corps, for Inch’ŏn. Almond had a relatively undistinguished record as a division commander in World War II, and the appointment surprised many, including Almond himself. Almond was concerned about his ability to execute two jobs, as MacArthur’s chief of staff and as commander of X Corps. “Well, we’ll all be home by Christmas,” MacArthur reassured him. “It is only a short operation. You’ll continue as my Chief of Staff and you can get any assistance you like.”58 Almond was a fiercely driven and competitive man with an all “consuming impatience with incompetence,”59 but he inspired little affection from his peers or subordinates. The mutual dislike between Almond and Maj. Gen. O. P. Smith, the commanding general of the First Marine Division assigned to X Corps, was well known. Smith, a cautious commander who believed that “you do it slow, but you should do it right,” was deeply suspicious of Almond. He later told the commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. Clifton Cates, that he had “little confidence in the tactical judgment of [Almond’s] X Corps or in the realism of their planning.”60 Their poor relations would have tragic consequences later in the war.

Despite the doubts and worries, the landing was a great success. At high tide early on September 15, the marines easily seized the small island of Wŏlmi-do, which controlled access to Inch’ŏn. The main force from the First Marine Division landed that afternoon in the next high-tide cycle. The landing caught the North Koreans by surprise; only a token force of two thousand North Korean soldiers defended the Inch’ŏn area. Within three days nearly seventy thousand men were put ashore.61

The Joint Chiefs and General Walker assumed that X Corps would be placed under the Eighth U.S. Army, but MacArthur kept it directly under his own control. MacArthur’s decision to divide the command surprised many. “When MacArthur insisted on keeping the X Corps under his own control, the feeling was that the Eighth Army was being slighted in favor of MacArthur’s ‘pets,’ “ recalled Ridgway. “While there was never any open expression of jealousy or unwillingness to cooperate, there was no mistaking the fact that the atmosphere of mutual trust so necessary to smooth cooperation was lacking.”62 The arrangement had lasting consequences. “The relationship between Almond and Walker was horrible,” recalled Col. John Michaelis. “I used to be in Walker’s office, briefing him or something, and the phone would ring. ‘Walker this is Almond.’ This is a two-star general talking to a three-star general. ‘I want you to do so and so.’ And Walker would ask, ‘Is this Almond speaking or Almond speaking for MacArthur?’ They just couldn’t get along.”63 Walker resented Almond’s special access to MacArthur. “Walker was very suspicious of Almond,” remembered Maj. Gen. John Chiles, Almond’s operations officer. “He thought Almond was putting words in MacArthur’s mouth because he was close to MacArthur and Walker wasn’t.”64 Almond’s position was an unenviable one. William McCaffrey, a regimental commander in X Corps, recalled that “Almond’s complete mystical faith in General MacArthur and his duties to his troops placed him in an extraordinary position of inner conflict.”65 This inner conflict became notably manifest in Almond’s relationship with his subordinate commanders, who felt that he was unresponsive to their needs and fighting conditions, because his greater goal was always to please the “big man” in Tokyo.

By September 25, the marines had entered Seoul. MacArthur declared it retaken even though less than half of the city was in UN hands. MacArthur’s gamble had paid off. The North Korean army, faced with encirclement and annihilation, rapidly retreated and disappeared “like wraiths into the hills.”66 For MacArthur, success of the Inch’ŏn plan and the liberation of Seoul were both a vindication and a professional triumph. Doubts expressed by General Omar Bradley, Collins, and other members of the JCS had fed into MacArthur’s paranoia that Washington was conspiring against him. But everything had gone just as MacArthur said it would. His honor and reputation had been strengthened to epic proportions. He saved South Korea. It was his brilliant plan that would bring victory. MacArthur was indignant when the Joint Chiefs questioned his authority to restore Syngman Rhee’s government, which, they said, “must have the approval of a higher authority.” “Your message is not understood,” replied MacArthur. “The existing government of the Republic has never ceased to function.”67 The Joint Chiefs simply allowed the matter to rest. It was the first of a series of MacArthur’s actions in Korea that the JCS failed to directly challenge. Ridgway later remarked, “A more subtle result of the Inch’ŏn triumph was the development of an almost superstitious regard for General MacArthur’s infallibility. Even his superiors, it seemed, began to doubt if they should question any of MacArthur’s decisions.”68 The more troubling result of Inch’ŏn, however, was that MacArthur ceased to have any doubts about himself.

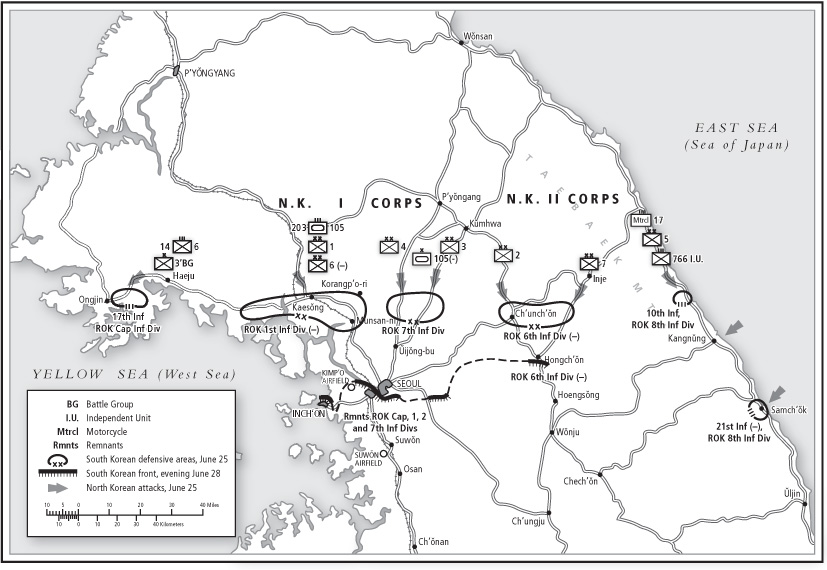

General MacArthur addresses guests at a ceremony held at the Capitol Building in Seoul to restore the capital of the Republic of Korea to its president, Syngman Rhee (in the background with glasses). (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

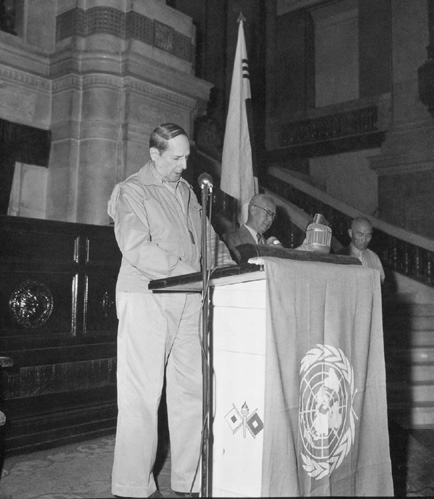

South Korean prisoners shot by retreating North Korean troops, October 6, 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Soon after Seoul’s liberation, disturbing reports of North Korean atrocities began to surface. “Everywhere the advancing columns found evidence of atrocities as the North Koreans hurried to liquidate political and military prisoners held in jails before they themselves retreated in the face of the U.N. advance,” stated the official U.S. Army history.69 The Associated Press reported that “mass graves, large and small, are being found daily in South Korean communities.”70 The Washington Post called a massacre site at Yangyŏng, thirty-five miles south of Seoul, “Red Buchenwald,” reporting that “in this Korean Red murder camp, 700 Korean civilians including children were executed.”71 The New York Times conveyed that at “Chunghŭng, near Kunsan, Communist soldiers armed with bamboo spears last Monday impaled eighty-two men, women and children after they took the village food supply.”72

The Jefferson City Post reported that “seeing the massacre stung the imagination.” It was a “coldly calculated massacre. Each man had been shot individually. Many apparently were clubbed to make sure they were dead. One man had a hatchet sticking to his head.”73 An American survivor of a massacre in Chinju related how the North Koreans had first made them dig their own graves before mowing them down with machine guns. “They tied us all together and shot us,” said Pvt. Carey Weinald. “I played dead.”74 North Korean soldiers and local leftists wantonly killed thousands. Women, the elderly, and children were not spared. In one especially brutal incident at Muan county on October 3, families selected for execution were bound and taken to the shore, where the adults were killed with knives, clubs, bamboo spears, and farm implements and then thrown into the sea. Children under ten were thrown into a deep well. The majority of those killed were women and children.75

Captured North Korean soldiers guarded by ROK Military Police remove the bodies of sixty-five political prisoners of the North Korean army that had been dumped into wells in the city of Hamhŭng, North Korea, October 19, 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

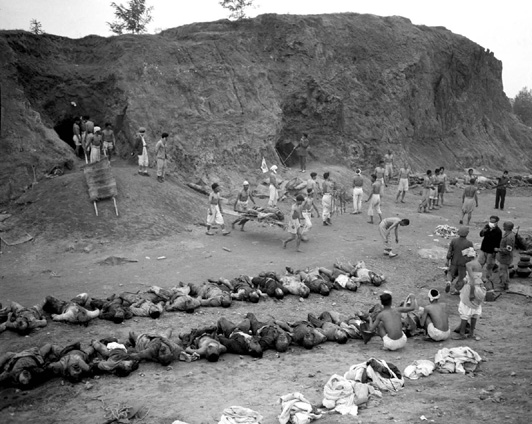

UN forces make another grim discovery of a North Korean massacre near Hamhŭng, where roughly three hundred bodies were taken out of a tunnel, October 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

In the courtyard of the Taejŏn central police station, a film crew records the oral testimony of a survivor of the Taejŏn massacre, October 31, 1950. These on-site recordings by survivors played an important role in creating the Taejŏn massacre as an iconic symbol of Red terror in both American and South Korean memories of the war. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

The North Korean massacres at Taejŏn prison became endowed with particularly powerful symbolic significance. The official U.S. history of the war described what had happened in Taejŏn as “one of the greatest mass killings of the entire Korean War,” estimating that five to seven thousand civilians and soldiers had been slaughtered.76 Private Herman Nelson described the horror of what he saw when he entered the prison: “After a GI thought he saw a body in an open well in the prison camp, an American officer ordered the well searched. A total of twenty-nine dead American soldiers were fished out of the well.” Over the next few days, more gruesome discoveries were made: “We discovered a church basement full of women slaughtered by the North Koreans. It was the same sickening sight we had witnessed a few days earlier.”77 Yi Chun-yŏng, who had been a South Korean prison guard at Taejŏn prison before the North Koreans came, vividly recalled the scene when he returned to the prison in early October:

I entered the prison and walked around and discovered the corpses. They were black and covered with flies. I was speechless. I couldn’t believe how cruelly these civilians were killed … Some had been shot and others seemed to have been killed by a blunt force that had cracked open their skull. I went to wells and found them full of bodies. We considered what to do … We obtained seven suspected communist prisoners and told them to line up the bodies. But the bodies were so decomposed that when we tried to pick them up, the flesh just slipped off. If they were clothed we could have picked them up by their clothing, but most were naked. The communist prisoners asked to be killed rather than handle these bodies, so we returned them to jail. I went to the Taejŏn City Hall to ask for help … By the next day, they had mobilized 300–400 people to clear up the bodies. I had them dig holes in the hill behind the prison to bury them … It took 2–3 days to do it. At first I thought of burying them individually, but there were just too many bodies, so we buried them in groups in larger holes. I don’t have an exact count, but it was between 400–500 people.78

The discovery of mass murder solidified in the minds of Americans and others that they were dealing with an “unnatural” enemy, one who had “no regard for human life” or who observed “no rules of war or humanity.” Like the “Mongolian hordes” of Asia’s past, this enemy “fights with a blend of Asiatic fatalism and Communist fanaticism.” “We are facing an army of barbarians in Korea,” wrote Hanson Baldwin of the New York Times, “but they are barbarians as trained, as relentless, as reckless of life, and as skilled in the tactics of the kind of war they fight as the hordes of Genghis Khan.” The North Korean “hordes,” like their Russian masters, inherited the particular “Mongolian penchant for cruelty” and used “weapons of fear and terror.”79

If the horrors of Taejŏn were a glimpse of an enemy not bound by laws of warfare, it was also apparent that the South Koreans were just as brutal. “[The South Korean security forces] murder to save themselves the trouble of escorting prisoners to the rear,” wrote an appalled John Osborne of Time and Life. “They murder civilians simply to get them out of the way or to avoid the trouble of searching and cross examining them. And they extort information … by means so brutal that they cannot be described.”80 The New York Times reported on July 13 that twelve hundred suspected communists had been executed by the South Korean police since the outbreak of hostilities, an estimate that was woefully inadequate. In the early days of the war, little effort was made by North or South Koreans to hide their atrocities. Telford Taylor, the former chief counsel for prosecution at Nuremberg, incensed by what he was reading in the newspapers, wrote to the New York Times that “it seems apparent, if we may take the press accounts at face value, that the atrocities have not all been the work of the North Koreans. The laws of war and war crimes trials are not weapons like bazookas and hand grenades to be used only against the enemy. The laws of war can be ‘law’ in the true sense only if they are of general application and applied to all sides.” He concluded, “We will make ourselves appear ridiculous and hypocritical if we condemn the conduct of the enemy when at the same time troops allied with us are with impunity executing prisoners by means of rifle butts applied to backbones.”81

The commission of atrocities by South Koreans was not the only issue that would make the Americans appear “ridiculous and hypocritical” to the world. From the beginning, the Americans faced a moral dilemma over what to do with the thousands of Korean refugees. It was a different kind of war from World War II, where the enemy was clearly identifiable on the battlefield. North Korean soldiers easily mixed with the refugees by disguising themselves in the ubiquitous white-cotton peasant clothing. “Time after time an American soldier would pass an innocent-looking bearded Korean farmer hoeing a rice paddy only to be confronted with the same figure throwing grenades at him in a dawn attack,” wrote Marguerite Higgins.82 In late July, the Associated Press reported an announcement by the South Korean government that civilians found making “enemy-like actions” would be executed.83 “The enemy has used the refugees to his advantage in many ways,” reported Ambassador Muccio on July 26, “by forcing [the refugees] south and so clogging the roads as to interfere with military movements, by using them as a channel for infiltration of agents, and most dangerous of all, by disguising their own troops as refugees, who after passing through our lines proceed, after dark, to produce hidden weapons, and then attack our units from the rear. Too often such attacks have been devastatingly successful.” Muccio also described a meeting at the South Korean Home Ministry on July 26 between American and South Korean officials where they concluded that leaflets warning people not to proceed south, and that if they did, they risked being fired upon, would be dropped north of the U.S. lines. “If refugees do appear from north of US lines they will receive warning shots, and if they then persist in advancing they will be shot.”84 These instructions were consistent with eyewitness accounts. No one willingly wanted to shoot innocent civilians, particularly women and children, but the nature of the war often forced American soldiers to do so. Colonel Paul Freeman, a regimental commander, admitted in an interview twenty years later, “This was the first time we had really encountered Communist cruelty … When we first met some of these North Korean attacks, they were driving civilians, elderly people, in front of them as shields. We had a very difficult time making our men fire into them. But if we didn’t fire into them, we were dead. I mean our people were dead. This was a very hard thing to do.”85

Another measure involved air strikes. “We heard numerous stories about American planes strafing civilians,” recalled H. K. Shin, who was just sixteen when he joined the ROK Military Police.86 One observer recalled that the First Cavalry Division’s commanding general, Maj. Gen. Hobart Gay, ordered a “scorched earth” policy: “In any withdrawal, all rural structures would be leveled, burned to the ground. No cover would be left for the enemy. Further, after a posted period, any Koreans found in the area between UN lines and the enemy would be considered hostile and shot on sight.”87 Distinctions between civilians and soldiers were blurred, and the brutality of the violence disturbed even the most seasoned soldier. “Much of this war is alien to the American tradition and shocking to the American mind,” observed John Osborne. “The attempt to win it is to force our men in the field to commit acts and attitudes of the utmost savagery.” This was not, he thought, “the inevitable savagery of combat in the field, but savagery in detail, the blotting out of villages where the enemy may be hiding, the shooting and shelling of refugees who may include North Koreans … or who may be screening an enemy march upon our positions.”88

Some of the worst atrocities were committed by South Koreans against South Koreans. In July 1950, the South Korean military and police conducted mass executions of suspected leftists before the arrival of the North Korean army.89 At Chŏngwŏn in central South Korea, the police killed hundreds of suspected communists. Pak Chŏng-gil, a young boy at the time, remembered the “perfidious” activities of the fleeing South Korean police: “I think they killed several thousand people there. Every day for seven straight days I saw four trucks in the morning and three trucks in the afternoon loaded with people.” The trucks, he said, all came back empty at night. At Nanju, in the southwest, police officers disguised as North Koreans stormed the village. When the people welcomed them, they were rounded up, taken to a field, and summarily executed.90 These and other massacres throughout South Korea in 1949 and 1950 demonstrated that the end of the Cheju and Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn Rebellions had not stopped the fratricidal bloodshed. South Korean security forces purged the army of leftists and communists and did their ruthless best to rid the countryside of communist guerilla groups formed by the remnants of the Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn rebels who had escaped into the mountains. Caught in the roundup of suspected leftists and communists were innocent civilians, including women and children who were summarily executed in the thousands in the name of fighting the communists. It is estimated that at least a hundred thousand South Koreans were killed in the summer of 1950. Most were members of the Bodo League (kungmin podo yŏnmaeng, National Guidance League), ostensibly created by the Rhee government in the summer of 1949 to rehabilitate leftists, but in reality it was a form of totalitarian state control of the people. Its logic required hapless and often illiterate farmers and fishermen to be enticed to join the league with promises of jobs, food, and other benefits to meet the quota imposed from Seoul. When North Korea invaded, the South Korean regime hastily took measures to eliminate those who might help the communists, and Bodo League members, mostly innocent of leftist leanings, were arbitrarily and summarily executed all over the country. Indeed, the hundred thousand estimate might be on the conservative side, as there were three hundred thousand members on the rolls of the league on the eve of the North Korean invasion.91

Remains of 114 Bodo League victims executed in July 1950 at Chŏngwŏn, Ch’ungbuk province, excavated by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2007. Remains of the victims reveal that they had been shot to death. (ROK TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION)

In an interview in November 2007, Chŏng Kwang-im recounted how her young farmer husband, who had joined the Bodo League in 1949, was summarily arrested and executed at Taejŏn:

One day the police came and asked where my husband, Pak Man-ho, was and I told them that he went away to make some money. They then arrested me. I spent the night in the jail. The next morning my husband came to the police station with our two children who had been crying for me all night. After he arrived they called for me. They gave me the children and took my husband without any chance for us to talk. At the urging of other people I awaited outside the prison. Around five in the morning a siren rang and trucks came. They loaded the trucks with prisoners, one at a time. We didn’t know where they were being taken to. I heard later they were taken to Sannae village.

Pak was executed in a remote valley near Sannae village. Chŏng later went to recover his remains, but she could not find him because the bodies had rapidly decomposed in the July heat. She never remarried and lived a life of suffering with her two sons, ostracized by her husband’s past as an alleged communist sympathizer.92

The remains of twenty-nine bodies were unearthed at the third site of the Kolryŏnggol, Sannae, Taejŏn in 2007. They were found face down with their knees bent, which suggests that the victims were killed execution-style. (ROK TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION)

Many American advisors, concerned and revolted by what they saw, filed reports with photographs. But the senior-level American response was decidedly ambivalent. Lieutenant Colonel Rollins Emmerich reported on the situation in Pusan, which had never fallen into enemy hands. He discovered that the local ROK Army commander, Col. Kim Chŏng-wŏn, planned “to execute some 3,500 suspected Communists.” He told Colonel Kim that the enemy would not reach Pusan soon and that “atrocities could not be condoned.” But “Colonel Kim was told that if the enemy did arrive to the outskirts of Pusan he would be permitted to open the gates of the prison and shoot the prisoners with machine guns.” Emmerich faced a similar situation in Taegu, where he managed to persuade South Korean authorities not to execute forty-five hundred prisoners. Taegu soon was threatened by the presence of North Koreans on its outskirts, and hundreds of the prisoners were executed. Donald Nichols, an air force intelligence officer, witnessed, photographed, and reported on the execution of eighteen hundred prisoners in Suwŏn, just south of Seoul. A North Korean press report that a thousand prisoners were executed in Inch’ŏn in late June 1950 was corroborated by an Eighth Army report on the execution of “400 Communists” there. Attempts were made to restrain the South Koreans, but the authorities receiving these reports, including MacArthur, were ambivalent. He had received numerous reports of the killings and atrocities committed by South Korean forces under his command, but he deferred to Ambassador Muccio, who merely asked the South Korean government to execute humanely and only after due process. MacArthur considered the situation a Korean “internal matter” and took no action.93

Ironically, one of the most egregious massacres by the South Koreans took place in the very vicinity where the North Koreans were accused of committing their most heinous war crimes. In early July, three weeks before Taejŏn fell to the NKPA, South Korean security forces executed thousands of suspected communists and leftists. Details of this incident have only recently been reported in South Korea. “After receiving news of the North Korean attack on Taejŏn,” reported the Wŏlgan chosŏn, a prominent South Korean monthly, in June 2000, “high ranking government and prisoner officials were too busy retreating to worry about the prisoners at Taejŏn prison.” As a result, “the responsibility ultimately fell on lower-ranking prison officials who did not want their men butchered alone by the revolting prisoners.”94 Yi Chun-yŏng, the Taejŏn prison guard who saw victims of North Korean killings in October, recalled the chaotic events in the days before the city fell. “We received a phone call from the Chief Prosecutor of the Justice Ministry and were ordered to execute all the leaders and officials of the Communist Party.” Seeking confirmation, Yi found the justice minister at the train station getting ready to evacuate south. The minister coolly told Yi “to tell the Commandant in charge to take action based on his own judgment.” Yi was furious. “If there hadn’t been others around, I would have shot him then and there,” Yi recalled indignantly. “The nation was in peril because people like him didn’t take any responsibility for any decision.”95 Minutes later, the minister was gone, taking one of the last trains out of Taejŏn.

There were only twenty-two men to guard and control the thousands of prisoners. Most were political prisoners charged with communist and leftist leanings. The local military police unit, led by Lt. Sim Yŏng-hyŏn, had arrived. Sim directed the prison guards to identify for execution any prisoners who had violated the Special Security Law, who had been involved in the 1948 Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn Uprising or the 1948–49 Cheju-do Rebellion, or who had been indicted for spying, and anyone else who had received a sentence of ten years or more. But time was short and they could not complete the sorting. In the end, all prisoners were executed. “The Commandant said that [executing all the prisoners] may become a political problem in the future, but there was nothing that could be done about the situation as there was no time to sort through all their backgrounds.”96 The prisoners, men and women, with their hands tied behind their backs, were loaded onto trucks. “Men from nearby villages were mobilized to dig trenches.” The prisoners were driven to various sites in the outskirts of the city and “taken to the trenches in groups of about ten. They were forced to kneel at the trench and bow their heads. The firing team was composed of military and civilian policemen. They put the barrel against the back of the head and fired.”97 “Even at point blank range, some were not killed outright,” Yi recalled. “Lt. Sim ordered me to confirm the executions and finish off those who were not dead. I was carrying a 45 caliber pistol unlike other guards who had smaller caliber pistols. I shot those who were still alive and squirming as I walked by them. I did as I was ordered.” There was one moment, however, that Yi will never forget:

As I walked by I heard behind me, “Sir, sir, I am not dead yet, please, sir, shoot me.” I turned around and saw a man who had worked in the mess hall. He had been imprisoned for theft and had one year left to serve out his ten year term … Why didn’t he say, “Hey you bastard, I am not dead. Shoot me, you bastard.” Why did he call me “sir” instead? He had no hostility towards me, and I suddenly felt a rush of anguish and respect for this man. He asked me to shoot him because he was suffering and I did.98

Yi later blamed higher authorities for what happened: “I don’t regret the death of communists who were convicted and sentenced to death, but the others … I wonder what kind of people led our nation who allowed them to be executed as well.”99 Although scattered reports about the mass executions managed to find their way into the foreign media, few stories ever reached the mainstream press because they were dismissed as communist propaganda. Alan Winnington, a British journalist for the communist Daily Worker, wrote what he had witnessed in Taejŏn when he arrived there with the NKPA:

Civilians about to be executed by South Korean security forces, Taejŏn, July 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Try to imagine Rangwul Valley, about five miles south-east of Taejon on the Yongdong road. Hills rise sharply from a level floor of 100 yards across and a quarter of a mile long. In the middle you can walk safely, though your shoes may roll on American cartridge cases, but at the sides you must be careful for the rest of the valley is thin crust of earth covering corpses of more than 7,000 men and women. One of the party with me stepped through nearly to his hip in rotting human tissue. Every few feet there is a fissure in the topsoil through which you can see into a gradually sinking mass of flesh and bone. The smell is something tangible and seeps into your throat. For days after I could taste the smell. All along the great death pits, waxy dead hands and feet, knees, elbows, twisted faces and heads burst open by bullets, stick through the soil … All six of the death pits are six feet deep and from six to twelve feet wide. The biggest is 200 yards long. Local peasants were forced at the rifle point to dig them, and it was from these that I got the facts. On July 4, 5 and 6, all prisoners from the jails and concentration camps around Taejon were taken in trucks to the valley, after first being bound with wire, knocked unconscious and packed like sardines on top of each other. So truckloads were driven to the valley and flung into pits. Peasants were made to cover the filled sections of the pits with soil.100

Few believed him at the time. When the city was retaken, victims of the earlier massacre perpetrated by the ROK forces were conflated with victims of the North Korean killings. Buried beneath the story of the North Korean slaughter, literally, was the forgotten story of the South Korean carnage. The raw brutality of a civil war wracked by deep and polarized ideological divide and decades of pent-up personal animosities exploded in the first few months of the war, causing a wound in Korean society, North and South, that remains raw to this day. The tides of cruelty continued with the tides of war as North and South Koreans tried to outdo each other in eliminating suspected collaborators and sympathizers of the other side as the front line moved north and south. In the context of the cold war, where clear lines between the “free world” and the “slave world,” and “civilization” and “barbarism,” needed to be starkly drawn, the messy civil war in Korea, with its moral ambiguities and vengeful deeds, had to be simplified. Historical forgetting, selective reporting, propagandistic self-deception, and a truly savage war and war crimes played major roles in the demonization of the other side. While the Western press continued to report on North Korean atrocities, particularly the merciless treatment of American POWs, critical coverage of South Korean brutality and U.S. operational excesses largely disappeared. Already, in the opening weeks of the war, a subtle yet distinct process of “forgetting” was beginning to take place.