At the end of August 1950, UN ground forces began to arrive in Korea, starting with the first contingent of British troops. The passage of UN Security Council Resolution 83 on June 27, 1950, obligated UN member states to consider sending assistance “to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.” Fifty-one member states were part of the United Nations upon its founding in 1945, and by the time of the Korean War, only eight more had joined. Out of these fifty-nine nations, forty-eight offered or sent forces or aid to South Korea. Seven non–UN member states also sent aid, bringing the total to fifty-five nations. Japan was under Allied occupation when the war started, but it was a critical support base for the war and was thus a member of the coalition. Germany was also under occupation but provided nonmilitary aid. Adding South Korea brought the final count of the coalition to fifty-eight. Of these, twenty-two nations, including one non–UN member, with “boots on the ground” in Korea formed the core of the coalition. Never before in modern history had so many nations committed themselves to a common political and military endeavor as they did during the Korean War (see appendix).1

There was a fundamental difference in the way the coalition in Korea was organized and operated compared to coalitions in other wars, such as the two world wars and the more recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Coalitions formed in wars before and after the Korean War normally consisted of discrete national units under national command, with coalitional integration or command and control achieved only at the highest level of command. For example, in World War II, the major Allied forces in the European theater of operations did not mix different nationalities below the corps level, except for very minor exceptions for specialized operations. In Korea, necessity, expedience, improvisation, and politics demanded a wholly different kind of coalition.

The unique character of the Korean coalition arose from a number of factors. First, the South Korean military was placed under UN/U.S. control because of its severely depleted and disorganized state after the first two weeks of fighting.2 Second, as an extension of the first, two pools of manpower were provided to UN/U.S. forces. One comprised the tens of thousands of Korean men known as KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to the United States Army) soldiers assigned to U.S. units, an arrangement that was later expanded to include British, Australian, Canadian, French, Dutch, and Belgian units. Most of the KATUSA soldiers were integrated down to the lowest level, the squad of some dozen men. The other pool of manpower was the Korean Service Corps (KSC), civilian laborers who were organized and led by ROK Army leaders to provide dedicated support to all UN/U.S. units. The ratio of laborers to soldiers was roughly one to two. Finally, non-U.S./Korean UN ground forces were sent not as large units or with a complete support structure and thus could not operate independently. Britain, Turkey, and Canada sent brigades (3,000–5,000 men), but most non-U.S./Korean UN ground forces were battalion size (about 1,000 men). All units were integrated into American divisions and corps. By 1952, every American division and corps had KATUSA soldiers and at least one UN battalion or brigade. The British Commonwealth ground forces (United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and India) did combine into a single division in the summer of 1951, an arrangement unprecedented for the Commonwealth, but it was subordinated to a U.S. corps and relied on American logistical support. The flow of campaigns and battles from late 1950 to mid-1951, under constant reorganization and re-subordination, led to complex mixes of nationalities.3

By the end of 1950, ten nations (in the order of arrival: the United Kingdom, the Philippines, Australia, Turkey, Thailand, the Netherlands, France, Greece, Canada, and New Zealand) had sent ground combat forces to join the Koreans and the Americans. Four more nations (Belgium, Luxembourg, Ethiopia, and Colombia) sent combat forces by the middle of 1951. Medical units from five other nations (Sweden, India, Denmark, Italy, and Norway) arrived by the end of 1951, while the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand significantly increased their contingents. By the end of 1951, the total strength of the non-U.S./ROK force was 35,000. This would grow to nearly 40,000 by July 1953.4

The British Commonwealth forces formed the majority of the coalition forces, about 60 percent (21,000–24,000). These forces went through several stages of reorganization, from the Commonwealth Brigade of British, Australian, Canadian, and Indian units in 1950 to, with reinforcements in 1951, the unique First Commonwealth Division formed in the summer of 1951. The unprecedented formation of the Commonwealth Brigade and the Commonwealth Division created political and high-level military difficulties, but at the lower level it was a relatively smooth process done efficiently and effectively, owing to a shared military heritage and culture and the use of English as a common language. The assignment of the Norwegian mobile army surgical hospital (NORMASH) also was done without significant problems. The Commonwealth units were the only forces besides the U.S. military that established a separate logistical system, easing the burden of support from the Eighth U.S. Army, which still had to provide fuel and fresh food.

The arrival of the 5,000 men of the Turkish Brigade in October 1950, however, posed far greater challenges. As soon as the situation stabilized after the victory at Inch’ŏn, a centralized transition and training center, the United Nations Reception Center (UNRC), was established near Taegu to help “clothe, equip, and provide familiarization training with US Army weapons and equipment to UN troops.” As the first UN troops to be processed, the Turks, during their three-week stay, provided the UNRC a much clearer picture of the kinds of problems the American commanders would be facing in commanding an international coalition. For example, bathing proved to be an unexpected challenge. “When showers were set up, it was found out that only one Turkish soldier at a time would bathe, until the problem of their unexpected modesty was solved by the soldiers themselves. Each man formed an individual cubicle by wrapping shelter halves around himself.”5

Language differences also posed a formidable barrier. Greek, Turkish, Thai, French, Flemish, Spanish, and Dutch as well as a number of other dialects “were among the tongues used in the UN ground [combat] units.” Added to these difficulties were the “Swedish, Norwegian, Italian, and several regional languages used by medical units supporting the combat forces.” Although the language barriers were never completely overcome, English was the lingua franca, and the burden of translation was left to UN units that “provided English-speaking personnel to translate training materials, operational orders and supply instructions into their own languages.”6

South Korean children present flowers to a Turkish officer (center) in charge of the first contingent of Turkish troops on their arrival in Pusan, October 18, 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Feeding the Turks was a special challenge, for most of them were Muslims and forbidden to eat pork. The Eighth Army devised a porkless diet manufactured by a Japanese fish cannery. The Turks also procured their “own stronger brand of coffee.” Since the staple of the Turkish diet was bread, they were given “three times the amount of bread issued to a US regiment as well as greater quantities of vegetable oil, olives, vinegar, dehydrated onions, and salt.”7

As with the Turks, culinary differences with the units from other countries initially posed great problems and stressed the U.S. ration system. It was difficult, for example, to get the Thai to eat “any sort of food except rice and pots of boiled vegetables, thick with peppers and hot sauces.” The Greeks did not eat corn, carrots, and asparagus and required olive oil for cooking. The Indians were mostly vegetarians. The Filipinos required additional rice, while the Belgians, French, and Dutch consumed greater quantities of bread and potatoes than the Americans did. The Greeks required special meals for religious days: “On Good Friday, they desired no meat in their rations, whereas for Greek Orthodox Easter, they required fifteen live lambs for their traditional feasts.”8

Troops in the Greek army prepare for a pork barbecue behind UN lines in Korea. Like other nationalities, the Greeks had their own unique dietary requirements, such as olive oil, raisins, and special flour, which were provided in sufficient quantities through their own channels. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

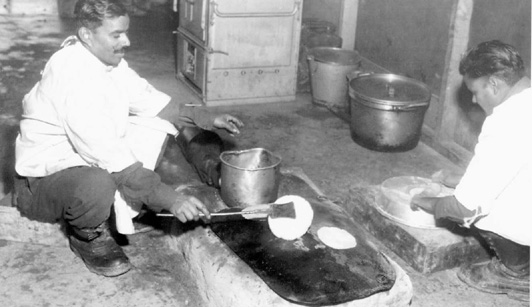

Indian cooks prepare traditional “chapati” flat bread. Unlike troops from Asian and European nations, which required large quantities of rice and potatoes, respectively, Indian troops required large quantities of wheat. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Clothing also produced its share of difficulties. The Thai, Filipino, and Greek soldiers required smaller clothing. A major challenge was combat boots. “It must be remembered that some of these troops were accustomed to wearing sandals, and therefore their feet were wide at the ball and narrow at the heel,” noted an American officer. Ethiopians were generally taller than Americans and their feet longer and narrower.9

The most critical area, weapons and ammunition, was not a major issue. Most UN troops, except for the Commonwealth units, were given American arms. Some contingents arrived already familiar with the U.S. Army, its procedures, and weapons. The Philippine army had been trained by the United States for many years, while the Greek army had recently undergone intense American training and equipping under Lt. Gen. James Van Fleet, to fight its communist insurgency. Van Fleet’s assumption of command of the Eighth Army a few months after the Greek battalion’s arrival no doubt provided an additional level of comfort to the Greeks.

The greatest challenge of the coalition, however, was integrating the ROK Army with the Eighth U.S. Army. Until the breakout from the Pusan perimeter in September 1950, ROK Army units were kept together at their own part of the front and controlled through the ROK Army headquarters. When the Eighth Army was reorganized for the breakout, the ROK First Division was assigned to an American corps, thus beginning the process of integrating ROK units with American forces.10

The need for men was so great in the summer of 1950 that the KATUSA program expanded rapidly, and by September over 19,000 KATUSA soldiers were assigned to the Eighth Army and X Corps.11 Integration of these Korean soldiers presented major difficulties at all levels of command. The success of the Inch’ŏn landing demonstrated the surprising efficiency of UN operations even at this early phase in the war. While most accounts of the operation have focused on the epic battles of the U.S. X Corps and its two American divisions, the First Marine Division and the U.S. Army Seventh Infantry Division, what is rarely noted is the role that the Korean soldiers and marines in the two divisions played in the events. The simpler arrangement was the attachment of the ROK Marine Corps Regiment to the U.S. First Marine Division.12 Such an attachment was routine and natural, and the regiment fought as a unit. However, the situation in the Seventh Division was quite different, because fully one-third of the division was composed of KATUSA soldiers.

American and KATUSA soldiers of the 27th Infantry Regiment advance toward Chinese forces at Kyŏngan-ri February 17, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

The Seventh Division had been on occupation duty in Japan at reduced strength. It became further depleted when men were transferred to the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry Divisions as they deployed to Korea in July 1950, thereby reducing the Seventh to less than half strength by late July. Essentially the division was not combat ready.13 Two measures were taken to bring it up to strength after it was selected for the Inch’ŏn operation. First, a large portion of the replacement flow from the United States was sent to the division. Second, MacArthur requested that the South Korean government provide Korean recruits to make up for the remaining shortfall. In mid-August nearly 9,000 Koreans arrived at Yokohama, Japan, “stunned, confused, and exhausted.”14 General “Johnnie” Walker reported to MacArthur, “They are right out of the rice paddies, and have nothing but shorts and straw hats.”15 Many had literally been dragged off the streets and arrived in Japan “in their native civilian clothes, white baggy cotton pants, small white jackets, [and] rubber shoes,” according to Maj. Spencer Edwards, the Seventh Division’s replacement officer.16 They had less than a month to become soldiers and get ready for an amphibious landing, one of the most complex and riskiest of military operations. In three weeks, 8,600 Koreans were clothed, equipped, and trained, however minimally, to join the 16,000 Americans of the Seventh Division embarking for Inch’ŏn.17 The challenges and obstacles were huge. Few, if any, spoke English. They had no military background or experience. Stocks of small-size uniform items were quickly exhausted. For many, the standard American rifle (the M1) was too long. Instead of forming all-Korean units, they were apportioned throughout the division at the rate of a hundred men per company or battery and integrated to the lowest echelon. Given that a standard company or battery may have about two hundred men, this was an enormous challenge. A buddy system of pairing individual Koreans with an American was used for assimilation, training, and control.18 The operational risks of the Inch’ŏn plan were magnified by the huge tactical risk of employing a division composed of the greenest troops, American and Korean, in which a third of the fighting force did not understand English.19

Fortunately, the First Marine Division, which landed first, was able to quickly secure a beachhead, allowing the Seventh Division to land without fighting for one. The Seventh Division soon entered combat to cut off the North Korean army’s retreat and to liberate Seoul. Their actions on the battlefield were predictably mixed. Major Edwards recalled that “some of the ROKs participated heroically and some of them disappeared at the first sign of danger. The great majority behaved just as any other troops with less than three weeks’ training would have—they just didn’t know what was going on.” Korean civilians watched in amazement as thousands of Koreans marched through the streets wearing the patch of an American unit that had been part of the occupation force in South Korea between 1945 and 1949. By the end of the Inch’ŏn-Seoul operations on October 3, the Seventh Division had suffered 572 casualties, of which 166 were KATUSA soldiers. By this time, thousands of other KATUSA soldiers had been assigned to and were fighting in all U.S. Army divisions.20

Korean Service Corps (KSC) laborers, near Suwŏn, February 5, 1951. In addition to the KATUSAs serving in U.S. units, the other pool of manpower was the KSC. Affectionately referred to as the “A-Frame Army” by American soldiers because of their wooden backpacks, at its peak the KSC had over 130,000 Koreans who were organized to provide direct support to non-Korean soldiers. The unarmed members of the KSC moved ammunition, supplies, and food to the front lines, traversing steep and rugged terrain that was otherwise inaccessible by vehicles. They also helped in the evacuation of wounded and deceased soldiers and the construction of defensive positions. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

KSC laborer, near Suwŏn, February 5, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Japanese nationals also played an important role in these operations. The majority of the landing ship tanks (LSTs) that the First Marine Division used at Inch’ŏn, thirty-seven of forty-seven, were, in fact, manned by Japanese crews.21 Furthermore, twenty Japanese minesweepers were contracted to help clear mines along the coastal areas. One was sunk during mine-clearing operations in Wŏnsan Harbor.22 Japanese nationals thus participated directly in combat operations. One Japanese national was even listed as an exchanged POW after the armistice.23 In addition to providing LST crews and minesweepers, Japan was literally the unsinkable base of support for the fighting. Nearly all military forces and supplies to Korea came from or transited through Japan. It also provided bases for air and naval operations.24 Troops were trained there before deployment, were treated there after being wounded, and played there during R&R leave. Japanese firms provisioned the UN forces and repaired their equipment.

Calling the Eighth Army a “U.S. Army” was thus a significant misnomer by the summer of 1951. More appropriate would have been the “UN Army in Korea” since less than half of its half-million men were Americans. Indeed, more than 50 percent of the fighting force were Koreans, of whom 20,000 were integrated into U.S., French, Dutch, and Belgian units. Some 28,000 soldiers from nineteen other nations joined them. The Eighth Army’s strength increased to nearly one million men by the time of the armistice, with 300,000 Americans, 590,000 Koreans, and 39,000 soldiers from other nations.25 No U.S. division since August 1950 was purely American, as KATUSA soldiers filled the ranks through all echelons.26 The U.S. divisions also had at least one UN battalion or brigade attached. Every U.S. corps had at least one ROK division. I Corps was probably the most diverse, composed of U.S. Army, ROK, and British Commonwealth divisions, which also included Turkish, Greek, and Norwegian contingents. Furthermore, since the summer of 1950 all non-Korean UN ground units were supported by the ROK Army’s KSC. At its height the Eighth Army’s KSC had 130,000 men to support 300,000 non-Korean soldiers.27

So why had all these nations come together under the UN flag to fight in Korea? Although each nation had its own reason to participate in the war, there was a broad commonality of factors, especially for the nations that sent combat forces. First and foremost, the war was seen as a test for the young United Nations and the concept of collective security it was supposed to uphold. Invoking the UN also invoked its most important member, the United States, and support to the UN also implied support for the Americans. Demonstrating this support became critical in the aftermath of World War II, for the United States emerged from the war as the most powerful and prosperous nation in the world, a world devastated by the destruction of that war and the ensuing strife and unrest of postcolonial struggles for independence, many involving indigenous communist movements. Communist insurgencies in Malaya for the United Kingdom and Indochina for France were particularly troubling. The United States had also been helping the Philippines battle its growing communist threat. In 1949, the Dutch pulled out of Indonesia, conceding defeat in the Indonesian War of Independence. Its new president, Sukarno, was sympathetic to communism. Most noncommunist member states of the United Nations thus felt an obligation to uphold the UN Charter and its principle of collective security. No member state felt this obligation more keenly than the three Western permanent members of the Security Council: the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Anticommunism and collective security were major shared ideologies of the nations that sent aid to Korea, especially those that deployed combat forces. The line was to be drawn against communism in general and against the Soviet Union in particular.

But idealistic ideology alone could not produce the kind of assistance the war called for, as most nations lacked the resources to provide it. Furthermore, many nations either were dependent on or wanted American assistance or commitment for economic development and security. Britain was particularly keen to maintain a “special relationship” with the United States and to secure an American commitment for Western European security. France, already deeply embroiled in a protracted war with Ho Chi Minh’s forces in Indochina, was eager to obtain American assistance for its own “cold war struggle” in Asia. France had convinced the Americans that, far from fighting a selfish colonial war, it was in fact defending the principles of freedom against communist world dictatorship. For its efforts in Korea and in Indochina, President Truman believed that France was entitled to a generous measure of American military and financial assistance since “these were two fronts in the same struggle.”28 Many nations reasoned that providing a contribution, especially combat forces, would serve not only their idealism but also, by getting in America’s good graces, their national interests. Largely because of their participation in the Korean War, Greece and Turkey, for example, were admitted to NATO in 1952. This was a triumph especially for Turkey, which had struggled to be accepted as part of Europe. Its large contribution in Korea, the legendary Turkish brigade, served to prove Turkey’s commitment to the West and its willingness to make sacrifices to uphold it.29

Soldiers of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders arrive in Pusan. Originally, the British government had decided to mobilize and deploy the Twenty-Ninth Infantry Brigade, a unit in the British strategic reserve force, but the brigade would not be ready on time. As a result, the Twenty-Seventh Brigade from Hong Kong was sent to Pusan as a quick stop measure until the Twenty-Ninth Brigade could be deployed. Only two of the brigade’s three battalions, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the Middlesex battalions, were sent, however. In order not to deplete the Hong Kong garrison completely, the Leicesters were left behind. Arriving on August 29 to bolster the Pusan perimeter, the Twenty-Seventh Brigade was the first non-U.S. UN ground force to enter the war. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

On November 20, 1950, the 60th Indian (Parachute) Field Ambulance, a mobile army surgical hospital, arrived and became part of the Twenty-Seventh Brigade. Britain pressured India for a large combat force, but Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to position India, which had only recently won its independence in 1947, as a leader of the underdeveloped countries in the UN and nonaligned with any major power. Nehru decided to contribute a medical unit as a commitment to the UN rather than to the Commonwealth, a symbol of its noncombatant status. The 60th Field Ambulance was an elite regular unit with personnel who were veterans of the Burma campaign during World War II serving in the British army. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

For Thailand, participation in the war helped to solve the special problem it had faced following the Second World War. Thailand had been a member of the Axis after signing an armistice with Japan in December 1941. Fighting in Korea largely “rehabilitated” the Thai in the eyes of the free world. Japan’s role in the Korean War was not so much as a willing participant, since it was still under American occupation in 1950, as it was of an unsuspecting bystander of a conflict from which it reaped tremendous benefit. The war was, as Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru once famously proclaimed, “a gift from the gods.” A war boom, stimulated by U.S. procurements for the war, put Japan’s economy back on track. Japanese industrial production during the conflict also laid the technological foundation for the subsequent development of the country’s industry.30 Japan’s central role in enabling the support of the UN forces created a paradox regarding the ending of the Allied occupation and the restoration of sovereignty. At first, military necessity made it preferable to delay any plans for Japanese independence until the Korean War was over. The Americans needed Japan’s full compliance for their war efforts in Korea. However, as the level of occupation forces dwindled and Japanese civil society became crucial in maintaining military support for the Korean War, the logic of denying the Japanese their independence was turned on its head as the Americans began to realize the necessity for placating, and even appeasing, the Japanese people as a prolonged occupation could degrade their cooperation and support. Nothing could have done this more powerfully than the end of the occupation, which occurred in April 1952. At the same time, even though the Japanese postwar constitution, drafted by the Americans, specifically forbade the maintenance of a military, the Korean War convinced both the Americans and the Japanese that Japan needed to be rearmed to defend itself against the communist and Soviet threat. Japan regained not only sovereignty, but a military as well. 31

A group of smiling Turkish officers pose with Korean Boy Scouts who welcomed their arrival at Pusan, October 19, 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

India, too, provided an interesting case. Although it sent a military medical unit that served with the Commonwealth forces, its motive was not to strengthen ties with Britain or the United States. Rather, India wanted to demonstrate its nonaligned and nonbelligerent policy. In line with this position, India agreed to chair the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission, which later oversaw the repatriation of POWs from both sides and provided a brigade-size custodial force to supervise the POW exchange after the armistice was signed. It also accepted a significant number of POWs from both sides who did not want to be repatriated to their countries. India’s record in Korea helped to validate its nonalignment policy and its position as a leader of the Nonaligned Movement (NAM) during the height of the cold war. 32

Ultimately, the most important outcome of the Korean War for all these nations was the legitimization of the United Nations. The failure of the League of Nations to confront Japan after it invaded Manchuria in 1931 had loomed large for many UN members. The successful coalition that fought in Korea erased doubts that the UN might be an equally empty promise; it had become a credible and effective international organization for peace and cooperation. For most countries that sent military forces to Korea, it was the first time in their history to participate in a war in a foreign land not for conquest, occupation, or defense of colonial territory. MacArthur’s spectacular victory at Inch’ŏn, however, would test the promise of that noble endeavor when UN forces were ordered to cross the 38th parallel into North Korea.