The war in Korea was on everyone’s mind as Americans sat down to enjoy their Thanksgiving feast. Truman reminded the American people “in church, chapel and synagogue, in their homes and in the busy walks of life, every day and everywhere, to pray for peace.”1 Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York made a plea “for clothing, blankets and money for the destitute in Korea.”2 Americans, Commonwealth soldiers, and other UN allies in Korea, some of whom had never eaten turkey, were treated to a lavish Thanksgiving dinner. The logistics of transporting tens of thousands of frozen turkeys, then thawing, cooking, and serving them on the front lines was an immense undertaking. And just so the American people would know what would be served, newspapers published the menu. Many soldiers later said it was the best meal they had ever eaten.

ARMY’S HOLIDAY MENU3

Roast turkey

Cranberry sauce

Sage dressing and giblet gravy

Snowflake potatoes and candied sweet potatoes

Fresh green peas and whole kernel corn

Waldorf salad

Lettuce, Thousand Island dressing

Ice cream and pumpkin pie

Mincemeat pie. Fruitcake.

Parker house rolls

Bread

Butter

Coffee

Fruit punch

The lavishness of the meal enhanced the optimism of the moment. Everyone thought the war was just about over and the “boys” would be home for Christmas. MacArthur stated that “regardless of Chinese intervention, the war will be finished by the end of the year.”4 The meal was as much a victory feast as it was a tribute to the sacrifices of the UN forces. Few knew that for many of these soldiers it would be their last good meal for months and for some, their last Thanksgiving meal.

The Eighth Army and X Corps resumed their advance the next morning. With MacArthur’s reassurance that the war would be over by the end of the year, there was little else on anyone’s mind but the upcoming Christmas holidays that promised a trip home. Everything had been going remarkably well. MacArthur was certain that Stratemeyer’s bombing campaign had destroyed all significant targets between the UN front lines and the Yalu River. Stratemeyer recalled MacArthur’s visit to Korea on November 24: “[He] was thrilled with the entire operation as was everyone in his party.”5 When IX Corps commander Maj. Gen. John Coulter told him that his troops were eager to reach the Yalu, Earnest Hoberecht of the United Press overheard MacArthur’s reply: “You can tell them when they get up to the Yalu, Jack, they can all come home. I want to make good my statement that they will get a Christmas dinner at home.”6 No one suspected, least of all MacArthur, that at that very moment almost 400,000 Chinese troops were about to strike.

Inspecting Thanksgiving dinner preparations at a mess hall, November 23, 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

The battlefront, November 23, 1950. (MAP ADAPTED FROM BILLY C. MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW, U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, 1990)

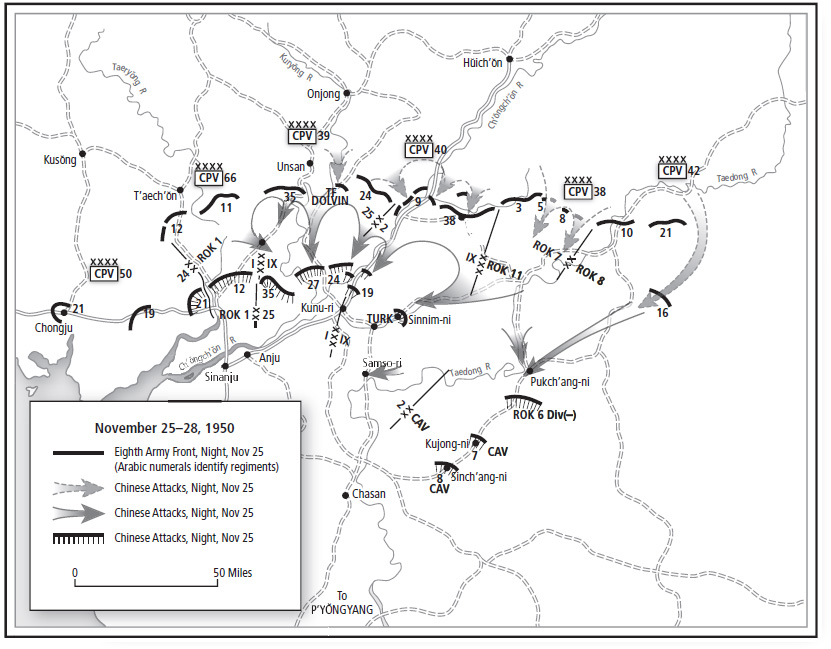

The CPV attacked ROK II Corps, again, on the evening of November 25. The gravity of the situation was not immediately apparent to General Walker. By nightfall, he received disquieting news from ROK II Corps that its divisions had encountered strong CPV “resistance.” Walker made no effort to reinforce the South Koreans.7 He soon realized that ROK II Corps was under a strong CPV attack that threatened to expose the army’s eastern flank. As ROK forces collapsed, the CPV began encircling the Eighth Army. In the face of the irresistible Chinese onslaught, Walker ordered the Eighth Army to break contact and retreat to more defensible terrains north of Seoul. Within ten days the Eighth Army had retreated 120 miles.

Battle of the Ch’ŏngch’ŏn, second Chinese offensive against the Eighth Army in North Korea, November 25–28, 1950. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

In the eastern sector, a large CPV force was planning to launch an attack against the X Corps, whose units were widely dispersed over hundreds of square miles of freezing barren mountains. The core of X Corps, the First Marine Division with elements of the Seventh Infantry Division, was scattered around the Changjin Reservoir. On November 27, the X Corps resumed its advance northward, unaware of the disaster that was unfolding against the Eighth Army. The winter of 1950–51 turned out to be one of the harshest on record. Temperatures were so cold that soldiers were routinely afflicted with frostbite, weapons did not function, vehicles and generators did not start, artillery shells failed to explode, and food always arrived frozen. Treating the wounded was particularly challenging. “Everything we had was frozen,” recalled Chester Lessenden, a medic. “Plasma froze and the bottles broke. We couldn’t use the plasma because it wouldn’t go into the solution and the tubes would clog up with particles. We couldn’t change dressings because we had to work with our gloves on to keep our hands from freezing.” The journalist Keyes Beech wrote that “it was so cold that men’s feet froze to the bottom of their socks and the skin peeled off when the socks were removed.”8 Two weeks earlier, Maj. Gen. O. P. Smith, the First Marine Division commander, had confided his deep concerns about the precariously exposed deployment of X Corps to the commandant of the Marine Corps. General Almond, he angrily vented, was pushing Smith to advance too fast and without taking the necessary precautions. This resulted in the division being strung out along a sixty-mile dirt road dominated by high grounds on both sides under harsh winter conditions, a situation Smith thought resulted from an unsound operational plan. “Time and again I have tried to tell the Corps Commander [Almond] that in a Marine division, he has a powerful instrument, but that it cannot help but lose its full effectiveness when dispersed,” Smith fumed.9

Disaster struck on the night of November 27, and thus began one of the greatest epic tales of tragedy and triumph in the annals of American military history.10 The CPV hit the widely dispersed X Corps everywhere simultaneously. Piecemeal destruction of the First Marine Division was prevented by Smith’s decision to concentrate the bulk of his division at three key villages around and near the Changjin Reservoir: Yudam-ni, on the northern side; Hagaru-ri, on the southern side about ten miles from Yudam-ni; and Kot’o-ri, a farther ten miles south of Hagaru-ri. It was another fifty miles from Hagaru-ri to Hŭngnam port, which was the X Corps’s main port for supply and evacuation, should it be necessary. Smith ordered the marines on the western side of the reservoir to fall in on Yudam-ni, and the task force from the Seventh Infantry Division, commanded by Col. Allan MacLean, on the eastern side to fall back to Hagaru-ri. On the morning of November 28, Almond made an impromptu visit to Hagaru-ri to confer with Smith and then visited the Seventh Division task force. Almond told MacLean to take the offensive. “The enemy who is delaying you for the moment is nothing more than remnants of Chinese divisions fleeing north,” Almond assured him. “We’re still attacking and we’re going all the way to the Yalu. Don’t let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen stop you.”11 However, with dire reports from the Eighth Army, MacArthur knew something was wrong and sent an alarmist cable to the JCS proclaiming that America now faced an “entirely new war.” It had finally dawned on him that the Chinese had come in with both feet. He ordered an immediate withdrawal.

The X Corps zone, North Korea. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

Battle of the Changjin Reservoir, North Korea, November 27–29, 1950. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

It was almost too late. During the night of November 28–29, the CPV besieged MacLean’s strung-out force. He ordered withdrawal at 2:00 a.m. “The snow was coming down in earnest,” recalled Maj. Hugh Robbins, “and the footing had become extremely slippery. Columns of foot soldiers had formed on the road on each side of the vehicles and had moved out in front … Many vehicles, which simply could not start because of the cold, had to be left behind, but none of the wounded was without transportation.” As the task force made its way south toward Hagaru-ri, MacLean was killed. Lieutenant Colonel Don Faith, a battalion commander under MacLean, took charge. The task force continued its treacherous march toward Hagaru-ri. Faith called for close air support to hold off the Chinese, and marine aircraft responded with napalm. But tragedy struck as some of the napalm hit the task force. “It hit and exploded in the middle of my squad,” recalled Pvt. James Ransone. “I don’t know how in the world the flames missed me … Men all around me burned.” Soon thereafter, Faith was killed and his command fell apart. “It was everyone for himself,” recalled Staff Sgt. Chester Bair. “The chain of command disappeared.” Over the next few days, survivors of the task force came limping, stumbling, and crawling across the great sweep of ice covering the reservoir to Hagaru-ri. The marines there used sleds to help them. A marine recalled, “Some of these men from Faith’s outfit were dragging themselves on the ice, others had gone crazy and were walking in circles.” “I was disoriented, exhausted, nearly frozen, hungry, and vomiting blood,” remembered Sergeant Bair. “The temperature at night was 20 or more degrees below zero. The wind was so strong it was hard to stand or walk on the ice.”12 The marines rescued about a thousand of the original twenty-five hundred troops of the task force. Of these, only four hundred were fit enough to continue to serve. The rest were evacuated to Japan.

As the disastrous drama unfolded on the eastern side of the reservoir, on the western side the marines successfully fell back to Yudam-ni. They were then ordered to withdraw farther south and join the marines at Hagaru-ri. Afterward, the whole force was to withdraw still farther south to Kot’o-ri to rejoin the rest of the First Marine Division and then move to Hŭngnam for evacuation. The marines from Yudam-ni broke through the Chinese forces and arrived at Hagaru-ri on December 4–5, creating a surge of confidence that they were going to survive the ordeal after all. Smith made headlines around the world when he refused to call the withdrawal a retreat. “Retreat hell!” he said. “We are not retreating. We’re just advancing in a different direction.”13 The truth of the matter was that there was no front or rear, and therefore nowhere to retreat to. What the marines were doing was attacking in another direction.14 The epic withdrawal of the marines at Changjin Reservoir became a cause for celebration. Headlines announced that calamity had been miraculously averted. “Marines Return Full of Fight after a Nightmare of Death,” announced the New York Times.15 “Marine Guts Turn Disaster into Day of Moral Triumph,” blazed the Washington Post. Jack Beth reported for the paper that “American Marines walked out of 12 days of freezing hell. These thousands of Leathernecks did it on guts. They turned their encirclement into one of the fightingest [sic] retreats in military history.”16 Time magazine wrote admiringly, “The running fight of the Marines and two battalions of the Army’s 7th Infantry Division from Hagaru … was a battle unparalleled in U.S. military history … It was an epic of great suffering and great valor.”17

The “triumph” might have been as much due to Chinese miscalculations as the bravery of the Americans. Had the Chinese hit Hagaru-ri on the night of November 27, they could have isolated the marines and soldiers to the north and thus destroyed in piecemeal most of the First Marine Division and the Seventh Division task force. Smith later told the New York Times, “They knew all about us all right, where we were and what we had, but I can’t understand their tactics. Instead of hitting us with everything at one place, they kept hitting us at different places. Had the Chinese decided to knock out the small Marine garrison at Hagaru-ri, the task of regrouping the forces into a full division would have been made immeasurably more difficult.”18 What Smith did not know is that the CPV had also taken a terrible beating from the cold, had suffered from lack of food, and had been tremendously hampered by UN air attacks. Tens of thousands of soldiers of the CPV Ninth Army Group died from freezing. The Chinese soldiers were supposed to have been issued winter uniforms, but many did not get them. They wrapped themselves in cotton scarves or covered themselves with “carpets.”19 Moreover, incessant UN air attacks limited movement to the nights. “We have no freedom of activities during the daytime,” General Peng complained to Mao. “Even though we have several times of the armed strength to surround them on four sides, fighting cannot end in a night.”20

Two weeks into the Chinese offensive, Mao worried about the adequacy of the CPV logistical network. “Are you entirely sure about supplying our army’s food and fodder by drawing on local resources?” an anxious Mao wrote to Peng. “Have the railroad lines from Sinŭiju and from Manp’o to P’yŏngyang been under rush construction? When will the construction be completed? Is it really possible for both railroads to transport all military supplies to the P’yŏngyang area?”21 The answers were apparent by the end of December, when the offensive began to run out of steam. Marshal Nie Rongzhen, who oversaw CPV logistics, described in his memoirs how he had stockpiled supplies, but that the “preparations had not been sufficient.”

During the Second Campaign, we had originally planned that two armies plus two divisions could handle campaign responsibilities in the western sector of the advance. But because we couldn’t transport the required amounts of rations up to the front, we were forced to cancel the two extra divisions … In the eastern sector, the troops which entered Korea had not made sufficient preparations and faced even greater difficulties. Not only did these troops not have enough to eat, their winter uniforms were too thin and could not protect their bodies from the cold. As a result, there occurred a large number of non-combat casualties. If we hadn’t had these logistical problems as well as certain other problems, the soldiers would have wiped out the U.S. First Marine Division at Changjin Reservoir.22

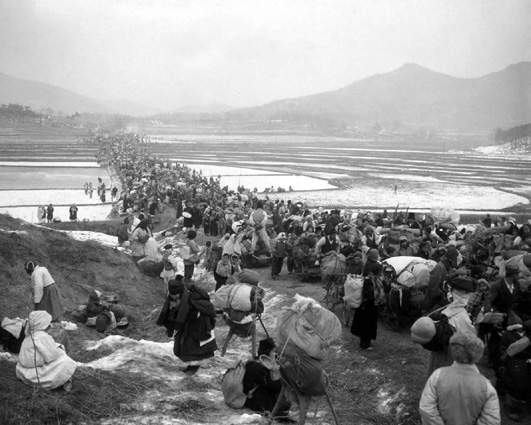

By late December, over a hundred thousand men in the X Corps, Americans and South Koreans, and, in a humanitarian triumph of the Changjin epic, more than ninety-eight thousand refugees were evacuated.23 After great pressure, Almond approved the evacuation of refugees despite concerns over the presence of communist infiltrators. One of the approximately two hundred ships assembled for the evacuation at Hŭngnam was the SS Meredith Victory, a merchant ship built during World War II. Commanded by Capt. Leonard LaRue, the vessel was later credited with “the greatest rescue operation by a single ship in the history of mankind.” As a cargo ship, the Meredith Victory was designed to accommodate fewer than sixty people, but Captain LaRue and his crew somehow managed to load fourteen thousand refugees on board. After a harsh three-day journey, the refugees, who had suffered cold, hunger, and lack of facilities, and grown by five newborns, were landed at Kŏje island on Christmas Day. There was not a single casualty, and the Meredith Victory became known as the “Ship of Miracles.”24

North Korean refugees attempting to board U.S. Navy ships at Hŭngnam, December 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

China’s intervention shocked the American public. “The nation received the fearful news from Korea with a strange-seeming calmness,” Time wrote. “It was the kind of fearful, half-disbelieving matter-of-factness with which many a man has reacted on learning that he has cancer or tuberculosis.” Unlike Pearl Harbor, which had “pealed out like a ball of fire,” the numbing facts of the defeat in Korea “seeped into the American consciousness slowly.” Days passed before it became apparent that UN forces had met a “crushing defeat.” The disaster and its implications became the subject of endless shocked conversations. “Some of them were almost monosyllabic, men meeting on the street sometimes simply stared at each other and then voiced the week’s oft-repeated phase, ‘It looks bad. Very bad.’”25

It did not take long for recriminations to follow. There were “peeved cracks” about MacArthur’s “home by Christmas” remarks, as well as criticism of the Truman administration. While most Americans accepted that war with China, perhaps even World War III, was now inevitable, it was MacArthur who had the greatest difficulty coming to terms with the disaster. Almost immediately, he launched a public attack on the administration. In late November he “cast discretion to the wind” and publicly expressed his frustration and resentment. He began with a written statement in the New York Times justifying his march north. “Every strategic and tactical movement made by the United Nations Command has been in complete accordance with United Nations resolutions and in compliance with the directives under which I operate,” MacArthur insisted. “It is historically inaccurate to attribute any degree of responsibility for the onslaught of the Chinese Communist armies to the strategic course of the campaign itself.” The next day, in an interview with U.S. News & World Report, MacArthur criticized the limitations the Truman administration had placed on “hot pursuit” and the bombing of Manchurian bases as “an enormous handicap, without precedent in history.” MacArthur also wrote to Hugh Baillie, president of United Press International, and came close to questioning the motives of allies, particularly the British, by suggesting that their “selfish” and “short-sighted” vision had been responsible for withholding support for his forces.26

Truman was predictably angry. Of this latest incident of MacArthur “shooting off his mouth,” Truman later wrote in his memoir that “he should have relieved General MacArthur then and there.” The reason he did not “was that I did not wish to have it appear as if he were being relieved because the offensive failed. I have never believed in going back on people when luck is against them and I did not intend to do it now.” Nevertheless, MacArthur “had to be told that the kinds of public statements he had been making were out of order.”27 On December 5, the president issued two directives that, though generally applicable to all “officials of the departments and agencies of the executive branch,” were really meant for MacArthur. The first required that “all public statements by U.S. government personnel, civilian and military, had to be cleared in advance by the State and Defense Departments.” The second ordered all officials and commanders to “exercise extreme caution in public statements … and to refrain from direct communication on military or foreign policy with newspapers, magazines, or other publicity media in the United States.”28 While Truman never directly blamed MacArthur for the failure of the UN forces, he did blame the general “for the manner in which he tried to excuse his failure.”29 Everyone in his administration had a share in the blame for the disaster, but MacArthur alone was unable to deal with the defeat with “dignity and good grace.” He had panicked, lashed out at the administration, and then lapsed into a profound depression.

The JCS met on December 3 to discuss the situation in Korea. MacArthur had written to the JCS that unless ground reinforcements “of the greatest magnitude” were promptly sent, hope for success “cannot be justified and steady attrition leading to final destruction can reasonably be contemplated.” For Bradley and the rest of the JCS, “this message and all it conveyed was profoundly dismaying. It seemed to be saying that MacArthur was throwing in the towel without the slightest effort to put up a fight.”30 The JCS seemed paralyzed about what to do and unable to leap beyond MacArthur’s doom and gloom.

In the end, it was the State Department that took control of the situation. It was thought that perhaps the United States should try to negotiate a cease-fire with the Russians. George Kennan, who was recalled from leave at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton to be an advisor to Secretary of State Acheson, counseled that engaging in negotiations with the Russians at such a time of weakness would do more harm than good, since “they would see no reason to spare us any of the humiliation of military disaster.” “The prerequisite to any satisfactory negotiation … is the demonstration that we have the capability to stabilize the front somewhere in the peninsula and to engage a large number of Communist forces for a long time.”31 UN forces had to stand firm to exert pressure on the enemy to force a cease-fire. Kennan, aware that Acheson was surrounded by “people who seemingly had no idea how to take defeat with dignity and good grace,” composed a note to raise the secretary’s spirits and strength to face what would no doubt be a trying period:

Dear Mr. Secretary:

There is one thing I would like to say in continuation of our discussion yesterday evening. In international, as in private, life what counts most is not really what happens to someone, but how he bears what happens to him. For this reason almost everything depends from here on out on the manner in which we Americans bear what is unquestionably a major failure and disaster to our national fortunes. If we accept it with candor, with dignity, with a resolve to absorb its lessons and to make it good by redoubled and determined effort—starting all over again, if necessary along the pattern of Pearl Harbor—we need lose neither our self-confidence nor our allies nor our power for bargaining, eventually, with the Russians. But if we try to conceal from our own people or from our allies the full measure of our misfortune, or permit ourselves to seek relief in any reactions of bluster or petulance or hysteria, we can easily find this crisis resolving itself into an irreparable deterioration of our world position—and of our confidence in ourselves.32

Acheson, moved, read the note to his staff. “We were being infected by a spirit of defeatism emanating from headquarters in Tokyo,” Acheson declared. The essential problem facing Washington’s political leaders was how to begin “to inspire a spirit of candor and redouble and determine our effort.” Acheson thought that the main issue was that “the Korea campaign had been cursed … by violent swings of exuberant optimism and the deepest depression and despair … what was needed was dogged determination to find a place to hold and fight the Chinese to a standstill.” This would be better than to consider withdrawal from Korea.33 Secretary of Defense George Marshall agreed. Acheson met with Truman and the matter was settled. Kennan recalled, “We lunched with Secretary Acheson. He had just been talking with the President. The President’s decision was, as always in great crises, clear, firm and unhesitating. He had no patience, Mr. Acheson told us, with the suggestion that we abandon Korea. We would stay and fight as long as possible.”34

Truman asked Army Chief of Staff J. Lawton Collins to go to Tokyo and Korea to assess the situation. Collins reported that although the military situation “remained serious, it was no longer critical.” The Eighth Army and X Corps were “calm and confident,” Collins recalled. “Throughout my visit, [Walker] seemed undismayed. While the situation was tight, I saw no signs of panic and left the next morning for the X Corps reassured that the Eighth Army could take care of itself.” Further, he anticipated “no serious trouble” in evacuating the X Corps from Hŭngnam. Collins concluded that the best solution was to evacuate the X Corps to Pusan, and the Eighth Army “should be gradually withdrawn toward Pusan,” where the united force could hold a defensive line “indefinitely.” Collins’s assessment was greeted “like a ray of sunshine.”35

While the crisis was unfolding, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee arrived in Washington on the afternoon of December 4 for urgent talks with Truman. The British were alarmed by Truman’s mention of the possible use of atomic weapons in Korea. If the prospect of a third world war in Korea was not enough to deal with, now came the unwelcome visit from “a Job’s comforter” in the form of Attlee. Ache-son found Attlee “persistently depressing,” whose thoughts resembled “a long withdrawing, melancholy sigh.” As soon as Attlee was reassured by Truman “that alarm over the safety of our troops would not drive us to some ill-considered use of atomic weapons,” the real purpose of his trip emerged. What Attlee wanted was to end the war in Korea so that the United States could “resume active participation in security for Europe.” He also wished that Britain be allowed “some participation … in any future decision to use nuclear weapons.” To end the fighting in Korea, Attlee urged Truman and Acheson to consider giving China UN membership and cutting Taiwan loose. Attlee argued that the UN position in Korea was so precarious that a price must be paid to extricate UN forces out of that conflict. Giving China a seat at the UN and withdrawing from both Korea and Taiwan would not be too high a price to pay, Attlee argued, for “there was nothing more important than retaining the good opinion of Asia.” Moreover, China was not a Soviet satellite, and if handled properly, “it might become an important counterpoise to Russia in Asia and the Far East.”36

Acheson vehemently disagreed. “To cut, run and abandon the whole enterprise was not acceptable conduct. There was a great difference between being forced out and getting out,” he responded.37 Furthermore, the security of the United States was more important than anyone’s “good opinion,” and the preservation of America’s defenses in the western Pacific and the Asian people’s confidence in America also provided “a path to securing their good opinion.” The only way to fight communism, he said, “was to eliminate it.” In the end, the British agreed to stay the course in Korea and accepted the United States’ refusal to rush to negotiations with China. In return, Truman implicitly agreed to keep the fighting limited and to abandon any plans for Korean unification. Truman also privately assured Attlee that he was not considering use of the atomic bomb and agreed to a broad pledge of close U.S-UK consultations on all global crises.38 Truman had, in effect, promised not to risk World War III without consulting the British. Talks with Attlee ended with a clear consensus, but they stirred up consternation in other circles. Republican Senator William Knowland from California, a severe critic of Truman and a strong supporter of Chiang Kai-shek who was known as the “Senator from Formosa,” said he saw “the making of a Far Eastern Munich.”39 Korean President Rhee stated he was “tremendously disappointed” that the Truman-Attlee conference ended “without a call for complete mobilization of the democratic world to fight against communism,” and thought that “it would have been better if the United Nations had not helped us at all if we are to be abandoned now.”40 But the furor eventually died down. UN forces would stay in Korea until a truce was negotiated. Once the front stabilized, a political basis for negotiations to end the conflict could begin. What no one could have guessed was just how long the negotiations would take.

Alarmed by rumors that the United States might use atomic weapons in Korea, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee (center) makes an urgent visit to Washington for talks with President Truman, December 4, 1950. (TRUMAN LIBRARY)

Meanwhile, as the X Corps was evacuating, the Eighth Army continued to fall back. General Walker ordered the evacuation of P’yŏngyang on December 3 and a “scorched earth policy” to destroy everything that might be of use to the enemy. Corporal Leonard Korgie, one of the last Americans to abandon the city, recalled the scene:

We went through P’yŏngyang at night and the whole city looked like it was burning. In one place, the engineers burned a rations dump about the size of a football field. God, it was a shame to see it in a land of hunger all the food going up in smoke. There was U.S. military equipment everywhere. I don’t know how much was destroyed … I believe we set on fire most of the villages we passed through. We weren’t going to give the Chinese too many places to shelter in during the rest of the winter.41

While the measure was to deny the enemy shelter and supply, the more immediate impact of the wholesale destruction of towns and villages was on the civilian population. North Korea was already a barren land with few resources, and the measure created an enormous refugee crisis in the middle of a harsh winter. When word spread that UN forces would not defend P’yŏngyang, three hundred thousand people living there fled. Barges and small boats ferried people across the Taedong River, but the UN forces destroyed many of these to prevent the refugees from crossing and clogging the roads the military needed for its own withdrawal. The civilians were also barred from crossing over bridges, so they sought alternative crossing routes. Some made their way over the ruins of the great steel bridge destroyed by American bombers earlier that summer. Others tried to wade across through freezing water. It was clear that nothing but inhumane suppression by force could deter the refugees.42 Captain Norman Allen recalled his torment about the refugees’ plight:

The refugees, awful moments there, deep memories. So pitiful, so desperate; they also hampered our movement by day and threatened our positions at night. Oh my God, what to do about them? The problem drove me wild. Once there were hundreds of them in one valley, maybe four hundred yards wide. We were tied in on the road with a company of another battalion. They came right up to our lines and we had to fire tracers over their heads to stop them from overrunning us … Shortly thereafter, both companies began receiving incoming mortar fire. The other company reported one of its platoons was overrun by the enemy who had mixed with refugees … When our road block reported that the refugees were pressing in on them and the pressure was growing, the men requested permission to fire. I asked who the refugees were, men, women, what? They replied: “Mostly women and children, but there are men dressed in white right behind them, men who look to us to be of military age.” I paused. The pause went on. The roadblock came on again, urgent, desperate, requesting permission to fire … I instructed the roadblock to fire full tracer along the final protective line, then to fall back to the high ground … I could not order firing on those thousands upon thousands of pitiful refugees.43

Fearing communist reprisals, refugees crawl perilously over the shattered girders of a bridge across the Taedong River in their desperate attempt to flee P’yŏngyang once it became clear that UN troops would not defend the city, December 4, 1950. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Some soldiers did open fire, and aircraft sometimes strafed the refugees. Hong Kyŏng-sŏn and his grandmother were among the refugees. Hong, a nineteen-year-old student and a Christian, had been part of the crowd that welcomed the UN liberation of the city in October. The news that the Americans had decided to abandon the city just three months later was an unbelievable shock. An even greater shock occurred when they were strafed by an aircraft with South Korean markings.44 At Chinnamp’o, a port thirty miles southwest of P’yŏngyang, UN forces were trying to evacuate the thousands of refugees who had streamed in. But of the fifty thousand refugees, only twenty thousand could be evacuated. On December 3, U.S. Navy Transport Squadron 1, which was en route to Japan from Inch’ŏn, was ordered to divert to Chinnamp’o to aid in the evacuation. The following morning, five ships reached the port and began loading the refugees. Lt. Jim Lampe, an officer in the squadron, had been born in Korea in a missionary family and had gone to school in P’yŏngyang as a child. His return to North Korea was a homecoming. Lampe was ordered to help evacuate those who had worked for the UN forces, as they would be the most likely targets for retribution. But, as Lampe wrote to his wife, this proved to be exceedingly difficult:

I had the police form a line of all those who worked for us, who hadn’t gotten out on the junks, to form a line, four abreast, with their families, along the pier area, to be taken to an LST by our small boats. It was morning now and that line was the most pathetic thing I had ever seen. We got into trouble when a group of several thousand who hadn’t worked for us, but wanted to get out, crashed through the guards and into the line … Each of these people had a pitiable small bundle with them [and] each thought that their life depended on their getting on one of those boats. Noon passed … all but twelve of our guards were pulled out and we backed down to the loading ramp. The crowd had absolutely no semblance of order now; it was just a solid mass of people, several thousand, all pushing … Women, the old ones, young girls and half naked babies in the cold, all crying, pleading … The last boat out. I felt like a monstrous murderer. A devil with a gun and pistol condemning these people to death … I was ashamed and embarrassed to be leaving and these helpless ones had to stay. I had to actually kick my foot free from a woman’s hand as I stepped in the boat. I felt like killing these people for making me feel like a murderer, and I wanted to blow my brains out for being the murderer. Big, warm, well-armed American! … I vowed never to go near Chinnamp’o again. How could I look at these people in the eyes!45

The refugees themselves also had to leave the more unfortunate behind. H. K. Shin remembered one tragic scene in which a small child, perhaps a year or two old, was crying at the side of the road next to her dead mother while a stream of refugees passed by. He recalled, “People passed by the child and dead mother shaking their heads as a desperate gesture of hopelessness and pity, but no one stopped to help the crying child. War had forced them to close their hearts and care for their own burdens.”46

The reaction in Seoul to the fall of P’yŏngyang was deadly. In the seemingly endless cycle of violence and retribution that characterized the war since it began, the South Korean government rounded up suspected “enemies” for summary execution. By the second week of December, mass executions of alleged communists by South Korean security forces took place on a large scale. An earlier period of retributive atrocities had taken place after the success of Inch’ŏn. The London Times on October 25, in a story titled “Seoul after Victory,” reported that “290 men and women and seven babies were detained … They squatted on the floors, unable to move or to lie down … (and) were beaten to insensibility” with rifle butts and bamboo sticks, and tortured “with the insertion of splinters under the finger nails.” The story concluded that while “the scene described has been, as is still being, repeated throughout Korea,” UN forces “feel either too helpless to intervene or believe attention drawn to the reprisals would be excellent material for Communist propaganda.”47 The daily executions after the fall of P’yŏngyang became too egregious to ignore. According to Western news sources, eight hundred persons described as convicted communists, collaborators, saboteurs, and murderers were executed during the second week of December alone. “A wave of disgust and anger erupted through American and British troops who either have witnessed or heard the firing squads in action in the Seoul area,” reported the Washington Post.48 A worried Muccio reported to Acheson that “17 persons had been killed, according to a British report, in a ‘brutal,’ and ‘criminal fashion’ raising concerns about the international backlash against the Rhee regime.”49

The British were also alarmed. A December 19 cable from the Foreign Office reported that “a massacre of 34 prisoners including women and children by South Korean police was witnessed by men of the Northumberland Fusiliers,” causing deep consternation among the British troops.50 Private Duncan, one of the witnesses, wrote to his member of Parliament.

Sir:

I wish to report an incident that occurred at a place three miles north of Seoul in Korea on December 12, 1950. Approximately forty emaciated and very subdued Koreans were taken about a mile from where I was stationed and shot while their hands were tied and also beaten by rifles … I myself saw the graves and also one of the bodies as they were very cruelly buried. The executioners were South Korean military police and the whole incident has caused a great stir and ill-feeling among the men of my unit … I write to tell you this as we are led to believe that we are fighting against such actions and I sincerely believe that our troops are wondering which side in Korea is right or wrong. Also my own feelings are so strong that I felt I must make known to someone of power this cruel incident.51

Other eyewitness accounts, like those of Fusilier William Hilder, were widely quoted by news organizations: “A truckload of prisoners was shot less than 150 feet from the camp where the British were eating their breakfast. The guards led them in groups of 10 into the trenches and then shot them in the back of the head. The women were screaming and the men wailing … Some of the guards went around with a machine gun firing bursts into those who didn’t die immediately. I walked away when the kiddies were shot. I didn’t like to see it.”52

President Rhee and other South Korean officials denied the killing of children, calling the reports “irresponsible and vicious slander,” but the on-site response was immediate and intense.53 Brigadier Tom Brodie, commander of the British Twenty-Ninth Infantry Brigade, was so incensed that he ordered his men to shoot any South Korean policemen attempting to carry out executions on the so-called Execution Hill, which was near his troops’ encampment. Brodie vehemently said that “he would not have people executed on my doorstep. My officers will stop executions in my area or within view of my troops.”54 Father Patrick O’Connor of the Catholic News Agency of Washington, D.C., and Father George Carroll, two priests in Seoul, sought to stop the executions by appealing directly to Rhee. Constantine Stavropoulos, principle secretary of the United Nations Commission for the Unification and Rehabilitation of Korea (UNCURK), demanded that Cho Pyŏng-ok, South Korea’s Home Minister, conduct an immediate investigation. UNCURK was created in October 1950 in anticipation of a reunified Korea as a result of UN operations. It was charged with overseeing the unification, reconstruction, and security of Korea as directed by the UN General Assembly. It arrived in Korea only days before the massive Chinese intervention at the end of November.55 The American mission requested that UNCURK itself conduct an investigation, which it did. The investigation largely confirmed the reports.56 Eventually, Rhee, who had initially ordered the executions speeded up, backed down and, conceding to international pressure, suspended the mass executions.57 Muccio reported, “Owing to public furor caused by second day’s executions and foreign correspondents cabling stories of mass executions without trial … government has suspended executions for time being.”58

Nevertheless, the credibility and legitimacy of the South Korean government, and by extension, the UN intervention, had already been badly damaged. Journalist René Cutforth reported on an Australian officer’s reaction to the inhumane and dire conditions of the Sŏdaemun (West Gate) Prison, which summed up the general mood: “This, my God, is a bloody fine set-up to waste good Australian lives over. I’m going to raise hell!”59 It was a sentiment shared by many who seriously questioned their country’s involvement in what was obviously a vicious civil war. The American public was angered and disgusted. Allen Neave of Highsville, Maryland, wrote to the Washington Post reflecting the prevalent feeling:

It has been said that the United Nations Troops are now fighting in Korea to preserve, among other things, decency. Are South Korean massacres more decent than others? Those same South Koreans are imploring the United Nations to hold off the bloody hordes from the North. Why? So that they can match, drop for drop, the quantity of mother’s and children’s blood spilled? Surely some of my buddies are not fighting for this!!60

International outrage forced Rhee to order an “inquiry into the conduct of the executions.” He also gave assurances to the British that “no further executions in the British area” would be carried out and that “the lieutenant in charge of the firing party is being held for court martial proceedings.” Rhee announced that he had accepted UNCURK’s recommendation for the mitigation of death sentences. He also announced amnesty for political prisoners.61 Finally, he assured the UN that “in the future, all executions will be carried out individually and not in groups of persons.”62

James Plimsoll, the Australian representative to UNCURK, was pleased by “the very satisfactory response” regarding the amnesty and future ROK policy on prisoners. Nevertheless, he could not help but wonder “to what extent this policy was actually being carried out.” In a February 1951 report to Canberra, Plimsoll admitted that “the Commission has no way of being sure that mass executions are not occurring; and the United States Embassy is equally in the dark.” Being in the dark, however, was exactly where the UN wanted to be. There were, after all, practical matters to consider in the conduct of the war. Although everyone deplored the mistreatment of prisoners, the UN was limited in what it could do to prevent it in the future because UN forces had come to depend on South Korean security forces to “check the infiltration of North Korean spies and agents, and in fighting guerillas in some regions.” Undermining their morale at such a critical time would make an already precarious situation worse. Internal reform of the security forces was needed, Plimsoll believed, not international censure. Plimsoll explained, “Some members of the Commission wanted a scathing report on the executions to be submitted to the General Assembly of the United Nations, but the majority opposed this.” He concluded, “No advantage can be gained by an act which might weaken the international support now being accorded the United Nations’ effort in Korea.” Plimsoll’s assessment was largely shared by MacArthur’s staff. Public condemnation of the executions could undermine the UN war effort and threaten the safety of UN troops. Humanitarian concerns had to give way to the military realities on the ground, which required cooperation with the South Koreans, who were responsible for the major share of the fighting. After the initial public outcry died down, MacArthur imposed censorship on all media dispatches of UN operations.63

Thousands of terror-stricken Koreans pack all the roads leading southward, fleeing the advance of the communists. In this picture, two families combine their efforts in a cart pulled by the fathers and pushed by the mothers and older children, January 5, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Confusion over the morality of the war, uncertainty over the reasons why American soldiers were fighting and dying, and fear of World War III with China’s intervention led to increasing alarm and skepticism in the American public that translated into an angry backlash against the Truman administration and against Acheson in particular. Truman’s approval rating plummeted to an all-time low, and his critics attacked him with increasing ferocity. In mid-December congressional Republicans overwhelmingly voted for the removal of Acheson from his office. Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin asserted that “the Korea deathtrap” could be laid squarely at “the doors of the Kremlin and those who sabotaged rearming, including Acheson and the President.”64 Even those who were disgusted by McCarthy’s anticommunist scare tactics questioned Acheson’s continued effectiveness. Walter Lippmann, whose liberal “Today and Tomorrow” column in the New York Herald Tribune was enormously influential, called on Acheson to resign, charging that the administration’s actions had led to “disaster abroad and disunity at home.”65 Nor did the revered George Marshall escape the barrage of attacks. Senator William Jenner, Republican from Indiana, accused him of playing the “role of a front man for traitors.” As a result, he said, the government had been turned into a “military dictatorship, run by communist-appeasing, communist-protecting, betrayer of America, Secretary of State Dean Acheson.”67 Acheson weathered the “shameful and nihilistic orgy” of abuse with humor. “Humor and contempt for the contemptible,” wrote Acheson, “proved as always, a shield and buckler against the ‘fiery darts of the wicked.’”68

Harry Truman (center) with Dean Acheson (left) and George Marshall, in good spirits despite an extremely difficult December. In one of his press conferences at the height of the attacks, Acheson was asked how the attacks were affecting him. He replied with a story of a poor fellow who had been wounded during the Indian wars in the West. “He was in bad shape,” said Acheson, “scalped, wounded with an arrow sticking into his back, and left for dead. As the surgeon prepared to extract the arrow, he asked the man, ‘Does it hurt very much?’ to which the wounded man replied, ‘Only when I laugh.’”66 (TRUMAN LIBRARY)

While humor enabled Acheson to endure what John Miller of the London Times had called “a revolt of the primitives against intelligence,” his only real protection against the vicious attacks was the complete confidence of Truman.69 On December 20, four days after he declared a state of emergency because the United States was in “great danger created by the Soviet Union,” Truman delivered an impassioned defense of his secretary of state. “How our position in the world would be improved by the retirement of Dean Acheson from public life is beyond me,” Truman declared. “If communism were to prevail in the world, as it shall not prevail, Dean Acheson would be one of the first, if not the first, to be shot by the enemies of liberty and Christianity.”70 Truman knew that Acheson’s departure would not be the end of “the revolt of the primitives,” but would merely become an invitation for further attacks against his administration, because the source of the anger was not Acheson or even the administration’s foreign policy, but the hysterical fear of communist subversion heightened by China’s unexpected entrance into an unpopular war.

The campaign against Acheson and Truman exacted a heavy toll. It tore at the fabric of American democracy and threatened to widen the war to mainland China. “[The McCarthyites] were operating on the principle that there can be no such thing as an honest difference of opinion, that whoever disagreed with them must be a traitor,” wrote Elmer Davis of Harper’s Magazine.71 Thus, while fighting a war against communism abroad, Americans were engaged in a “cold civil war” at home. The result, according to Acheson, was that “the government’s foreign and civil services, universities, and China-studies programs took a decade to recover from this sadistic pogrom.”72 The situation could have been far worse, however, had it not been for the new commander of the Eighth Army, Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, who was able to quickly reverse the situation in Korea. Ridgway’s leadership prevented a defeat in Korea that would surely have allowed anticommunist forces to paralyze America’s democratic institutions and give credence to MacArthur’s belligerent calls to expand the war to China and hence World War III. Ridgway could offer only the possibility of a limited victory, but the stabilization of the battlefield eventually led to the demise of the “revolt of the primitives.”

Ridgway’s appearance in Korea was the result of a traffic accident in which General Walker was killed on his way to Ŭijong-bu north of Seoul.73 Before his death, serious questions had been raised about Walker’s leadership. His decision to abandon P’yŏngyang without a fight was seen as “one of the most important tactical mistakes of the war.”74 With uncontested airpower and strong armor forces, the Eighth Army had a good chance of turning back the Chinese. Some correspondents thought the withdrawal was an “uncontrolled bug-out,” nothing like the measured, successful retreat and evacuation of the X Corps. Walker became despondent; his professional reputation was now stained by the disastrous retreat while his leadership during the desperate days of the Pusan perimeter seemed all but forgotten.75

Walker’s apprehension about his future was warranted. Only a few weeks earlier General Collins had had a discussion with MacArthur about replacing Walker with Ridgway. When news of the tragic traffic accident reached MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs, Collins was able to obtain almost immediate clearance for Ridgway’s assignment. Three days after Walker’s death, Ridgway was on his way to Tokyo. MacArthur and Ridgway had been acquaintances for years, but they were never particularly close. Ridgway had served under MacArthur at West Point in 1919 when the latter was the superintendent of the academy. Unlike his flamboyant boss, Ridgway was known for his no-nonsense, hands-on approach. His trademark habit of strapping a hand grenade to the webbing harness on his chest was interpreted as showmanship, but Ridgway explained that “[The grenades] were purely utilitarian … Many a time in Europe and Korea, men in tight spots blasted their way out with hand grenades.”76 If anything, the grenades symbolized his view of himself as both a leader and a common soldier.

MacArthur greeted Ridgway warmly at their first meeting, in Tokyo on the day after Christmas 1950. Ridgway asked whether he might go on the offensive should an opportunity present itself. MacArthur simply replied, “The Eighth Army is yours, Matt. Do what you like with it.”77 MacArthur’s latitude for Ridgway, something that he had not extended to either Walker or Almond, was not so much a reflection of special confidence as it was an indication of his troubled state of mind. MacArthur had become deeply despondent over the consequences of China’s intervention. He had staked his reputation on the Chinese not entering, or if they did, that he could easily deal with them. “The Red Chinese had made a fool of the infallible ‘military genius’,” Bradley later observed.78 Now the situation appeared close to hopeless. What else could MacArthur do but give Ridgway his full support? MacArthur was unsure that UN forces could hold the Chinese back, and he continued to urge expanding the war to mainland China. The Joint Chiefs, however, strongly disagreed. Their directive of December 29 stated that “Korea is not the place to fight a major war” and that MacArthur must continue to defend while “inflicting such damage to hostile forces in Korea as is possible.” Instead of following the directive, MacArthur challenged the Joint Chiefs, arguing that the Chinese war-making capacity should be crippled by air and by a naval blockade. He also urged acceptance of Chiang Kai-shek’s offer of Nationalist troops. MacArthur presented the JCS with two alternatives: expand the war to China or withdraw to Japan. In arguing for the former, he risked World War III, a risk the Truman administration was not willing to take.

While the JCS and MacArthur sparred, Ridgway was planning to go on the offensive. He thought the notion of withdrawing to Japan absurd. UN forces had complete control of the skies and the seas and had vastly superior weapons and logistical support at its disposal. There was no reason why the Eighth Army could not get back on its feet. “My morale was at the highest of all times,” he later confided. “I didn’t have the slightest doubt that we would take the offensive. It was just a question of giving us a little time.”79 Upon his arrival in Korea on December 27, Ridgway called on Ambassador Muccio and President Rhee. Muccio was deeply worried about the rumors that UN forces were preparing to evacuate to Japan. Ridgway reassured both men that he and the UN were staying. He told them that “he planned to go on the offensive again as soon as we could marshal our forces.”80 Ridgway then toured the front, in an open jeep in freezing weather, and within forty-eight hours had met every corps commander and all but one division commander. He did not like what he saw, later writing, “Every command post I visited gave me the same sense of lost confidence and lack of spirit. The leaders, from sergeants on up, seemed unresponsive, reluctant to answer my questions.”81 The challenge was infusing this demoralized force with renewed spirit. His first step was to take formal control of the X Corps and unify the UNC under him. As William McCaffrey, Almond’s deputy chief of staff, recalled, “Ridgway told him [Almond] how things were going to go in Eighth Army from now on. Almond got the point, and that’s how it went. There wasn’t any question as to who was the army commander. Ridgway straightened out that ridiculous situation the first day.”82

Ridgway made other major changes as well. Major General Coulter of the IX Corps, who had performed badly when the Chinese attacked, was promoted out of his position. Ridgway retained his friend Maj. Gen. Frank Milburn, commander of I Corps, who also did not do well, but kept him under close rein. Officers who did not perform up to standard or who were deemed wanting were sent packing. Once, Ridgway attended a briefing given by Colonel Jeter, the I Corps operations officer, who was briefing his plans for “defending in successive positions.” Ridgway interrupted him and asked what his attack plans were. Puzzled, Jeter said there were no attack plans since the Eighth Army was in retreat. Ridgway relieved him on the spot.83 News of Jeter’s fate spread quickly among the ranks. While some within I Corps staff resented Ridgway’s treatment of Jeter, it did have the kind of shock effect that the new commander had hoped for. Ridgway made it clear that he intended to move the Eighth Army forward, not backward. Thus was born a grudging nickname that, while originally intended as an insult, soon became a badge of honor: “Wrong Way Ridgway.”

While dramatic changes were made at the top, Ridgway also sought to inspire transformation from the bottom. He visited the troops, listened to their complaints, and shared in their hardships. “It is the little things that count,” he recalled of his efforts to uplift his soldiers. One soldier had complained to him that there was never enough stationery to write letters home, so the general “had somebody send up a supply of stationery.” Ridgway became known for passing out extra gloves. “Any soldier up there, you know, the temperature is down below or around zero and his hands are cold and raw, and sure would like to have a pair of gloves; a thousand and one little things like that.” Ridgway was strict about officers setting good examples. “I never would permit a senior officer to ride about in an automobile, I mean of any kind. He had to be in an open jeep with the top down for safety. That does the GI good too, to see his commander up there, as cold as hell.”84 Blessed with a phenomenal memory, Ridgway astonished his soldiers by remembering their names. According to one account, Ridgway could recall “without hesitation four or five thousand names, half of whom were enlisted men.”85 It was his acute attention to detail, and to the names and needs of his men, that made Ridgway’s leadership so effective, especially with soldiers who believed that they had been ill treated, betrayed, and forgotten. His aide-de-camp, Walter F. Winton Jr., recalled,

If you had been a betting man, you would not have bet an awful lot on the United Nations Forces at this juncture in history. A short summation of the situation: weather terrible, Chinese ferocious, and morale stinko. The Eighth Army Commander, General Ridgway, took hold of that thing like a magician taking hold of a bunch of handkerchiefs out of a hat, like so … He didn’t turn the Army around by being mean to people, by shooting people, by relieving people, by chopping people’s heads off, or by striking fear; quite the opposite. He breathed humanity into that operation … He effected gradual and orderly relief. He kept alive the old spirit of the offensive, the spirit of the bayonet; call it what you will. Talk about practicing what he preaches. During the time he was in command of the Eighth Army, in Korea, I can hardly think of half a dozen days when he was not under hostile fire. This impressed me. The troops knew it and once they got the idea that somebody was looking out for them, and not for himself, the miracle happened.86

As Ridgway was breathing new life into his army, the Chinese continued their long trek south. Rest halts were few. It was deathly cold. Almost everything had to be carried on men’s backs or by pack animals since they had little motorized transport. Each man carried rations for about a week consisting of soya flour, tea, rice, some sugar, and perhaps a small can of meat.87 The lengthening supply line meant that replenishing even these meager supplies became more difficult. Hunger became endemic. UN air raids disrupted the CPV’s march and supply lines, and the bombing of villages left few places for the soldiers to seek shelter. One Chinese soldier recalled, “One night it was reported to me that an entire squad’s post collapsed in the snowstorm. When I rushed to the squad’s post in the trench, I was dumbfounded by the scene, all nine unconscious and covered by layers of snow. As those bodies under the thin uniforms began to turn cold, I also realized that their food bags were empty. None of them survived to participate in the offensive attack.”88

Generals Matthew B. Ridgway (left) and Edward Almond, February 15, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

By January 1951, the Chinese army was badly in need of a rest. General Peng, cautious by nature, understood the limitations of his army and what he could achieve against a technologically superior force with near-total command of the skies. He was wary of underestimating the enemy. After the CPV’s victorious second campaign in late November, Peng requested permission to regroup his forces and rest over the winter. Logistical problems, hunger, cold, and exhaustion had made it almost impossible to continue. “Let [the troops] stop in areas dozens of lis north of the parallel, allowing the enemy to control the parallel, so that we will be able to destroy the enemy’s main force the next year,” Peng wrote to Mao. But Mao was impatient and wanted the third offensive to begin as soon as possible, by no later than early January, much earlier than what Peng thought wise or feasible. “Our army must cross the 38th parallel,” Mao wrote back to Peng in mid-December. “It will be most unfavorable in political terms if [our forces] don’t reach the 38th parallel and stop north of it.” Peng warned Mao of “a rise of unrealistic optimism for a quicker victory from various parts” and suggested a more prudent advance.89 Peng continued to press his case to Mao, laying bare the full horror of what his army was facing in Korea: “Most of the overcoats for the various corps have not yet arrived, nor have the cotton-padded shoes for the 42nd Army.” By this time, the shoes had been mostly worn out, and some of the soldiers had been forced to go barefoot. “Cooking oil, grain, and vegetables are either unavailable or late in arrival, and the physical strength of our army unit has weakened, with increasing numbers of sick soldiers.” The situation was going from bad to worse, Peng warned Mao. “If there is no remedy for quick relief, the war will be protracted.”90 But Mao could not be persuaded to postpone the offensive. Peng arrived at a compromise solution: he would scale down the size of the military operation and stop whenever it became necessary.91 The CPV would adopt a “gradual plan of advancement.”92 He knew that UN morale was low, but there were still a quarter of a million UN forces, and Peng worried that as they began to dig in, it would become increasingly costly to assault them and their wall of firepower. Mao finally agreed.

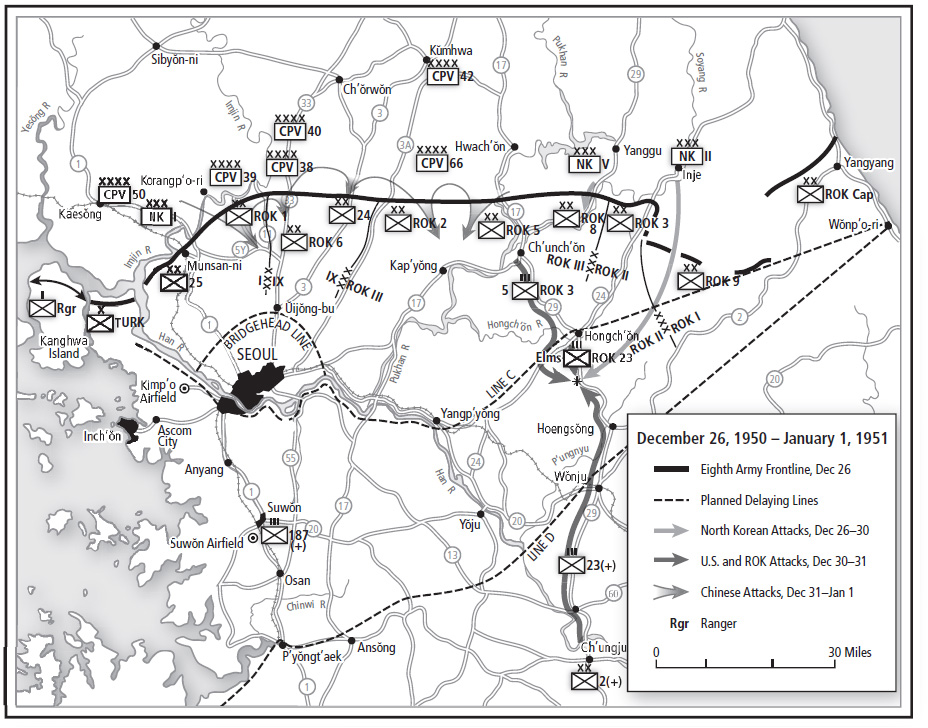

Chinese third offensive, December 1950–January 1951. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

The CPV attack pushed UN forces across the Han River.93 Seoul fell on January 4, the third time the city had changed hands since the war began. While the withdrawal was not without some disorder, Ridgway had by this time, less than ten days after his arrival, revived the Eighth Army’s spirits. Ridgway established a strong defensive line about sixty miles south of Seoul. After Seoul’s fall, Peng pushed south for a few more days and then ordered a general halt. His exhausted soldiers were simply in no condition to continue, and he feared that UN forces were trying to lure his army into vainly assaulting fortified positions. Peng’s forces, including the NKPA, withdrew several miles to rest and regroup. When the third offensive ended, China had “only 280,000 poorly supplied and very exhausted troops facing 230,000 well-equipped UN and ROK forces.”94 Peng’s forces had been reduced in half, and the winter months were making it difficult to get supplies through to those who remained.95 Zhang Da, who was only seventeen years old when he enlisted to fight in Korea, remembered that many soldiers continued to “suffer severe frostbite to their hands and their feet.” The food was also very poor, with the main staple being “baked dry flour with rice, sorghum or ship biscuits.”96 A captured diary written by a Chinese officer vividly recounted what Peng and his army were up against during that harsh winter:

Refugees again flee from Seoul, January 5, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Difficulties: 1) We have been troubled on the march due to icy roads. 2) we are exhausted from incessant night marches. To make matters worse, when we should be resting during the day, we cannot take a nap due to enemy air activity. 3) Due to a shortage of shoes, almost all the soldiers are suffering from frostbite. 4) We have had to cross rivers with our uniforms on during combat, which has resulted in severe frostbite. 5) The fighting is becoming critical due to lack of ammo and food. 6) Lack of lubrication causes untimely rifle jams when firing. 7) We have had to carry heavy equipment on our backs, we are always heavily burdened when marching. 8) The physical condition of the soldiers has been getting worse as they have to hide in shelters all day long, and fight only at night or during enemy air assaults. 9) When reconnoitering at night disguised in civilian clothing, it is very difficult to carry out the mission because of language difficulties.

Morale of the soldiers of our unit: Enemy air strikes frighten the soldiers most of all. The most unbearable labor they have to endure is to carry heavy equipment on their backs when climbing mountain ridges. Their conviction that they will win the war is wavering.97

On January 11, Mao instructed Peng to reorganize the CPV and defend Seoul, Inch’ŏn, and the areas north of the 38th parallel, while the NKPA was to be resupplied and continue their attack south. Kim Il Sung was delighted. Kim, Pak Hŏn-yŏng, and Peng met to discuss the new plan. Peng was wary. He thought Kim’s focus on expanding territory without destroying the enemy was pointless. Furthermore, sending the North Koreans ahead alone assumed that the communists held the advantage and that UN troops would eventually retreat from the peninsula, something Peng did not believe was likely to happen. He knew that the NKPA was not strong enough to destroy the UN forces on its own, and with the latter’s well-defended positions and superior firepower, the NKPA would surely fail. But Pak countered that the UN forces need not be annihilated, only pursued. Recent reports from Moscow indicated that the UN forces would soon withdraw from the peninsula. All they needed was a little prodding. Peng retorted that a few more American divisions would have to be destroyed before the UN forces withdrew. Kim responded by suggesting again his idea of sending NKPA forces south now and CPV forces to follow after resting for a month. Peng impatiently “raised his voice” and emphatically declared that “they [Kim and Pak] were wrong and that they were dreaming.” “In the past, you said that the US would never send troops,” he fumed. “You never thought about what you would do if they did send troops. Now you say that the American army will definitely withdraw from Korea, but you are not considering what to do if the American army doesn’t withdraw.” He scolded the Koreans for “hoping for a quick victory,” which was “only going to prolong the war” and “lead … to disaster.” Peng concluded that “to reorganize and re-supply, the Volunteer Army needs two months, not one day less, maybe even three [months]. Without considerable preparation, not one division can advance south. I resolutely oppose this mistake you are making in misunderstanding the enemy. If you think I am not doing my job well, you can fire me, court martial me, or even kill me.” When Stalin was informed of the heated exchange, he sensed a crack in the alliance and sided with Peng. “The leadership of the CVA [Chinese Volunteer Army] is correct. Undoubtedly the truth lies with commander Peng Dehuai.”98

While the Chinese halted, MacArthur continued his calls to widen the war with China. What disturbed the JCS most, however, was MacArthur’s “negative and defeatist tone about the Eighth Army,” painting the bleakest possible picture of the situation in Korea. This was all the more puzzling since it was in sharp contrast to the optimistic reports from Ridgway. “It indicated,” wrote Bradley, “that MacArthur might well be completely out of touch with the battlefield.” MacArthur reported that the UNC was not strong enough to hold Korea and protect Japan. He reported gloomily that his troops were “embittered” and tired and that “their morale will become a serious threat to their battlefield efficiency unless the political basis upon which they are asked to trade life for time is clearly delineated, fully understood, and so impelling that the hazards of battle are cheerfully accepted.”99

MacArthur’s message of potential doom was received grimly in Washington. Truman was deeply disturbed.100 Rusk later remarked that “when a general complains of the morale of his troops, the time has come to look at his own.” Acheson, unconvinced by the general’s ominous predictions, was also suspicious and privately concluded that MacArthur was “incurably recalcitrant and basically disloyal to the purposes of the Commander-in-Chief.”101 The JCS told MacArthur to hold out as long as possible and to withdraw to Japan if no other recourse was available, while the administration considers contingency military and nonmilitary courses of action against China. Generals Collins and Vandenberg then flew to Japan and Korea on a fact-finding mission. What they found surprised and heartened them. Ridgway was optimistic and confident. Both men were impressed with how Ridgway had revived the Eighth Army. There was no doubt in their minds that the UN forces could and would stay and fight in Korea. “Morale very satisfactory considering condition,” reported Collins to Washington. “On the whole, Eighth Army now in position and prepared to punish severely the enemy.”102 It was their opinion that, short of Soviet intervention, the Eighth Army could continue operations in Korea without endangering the security of either itself or Japan. From then on, there was no further discussion about blockading or bombing China. Ridgway had made that option moot.

But Ridgway’s success was also MacArthur’s failure, for it undercut his power to direct and influence events in Korea. The JCS distrusted MacArthur and sought information on Korea directly from Ridgway, as MacArthur was seen as untrustworthy. “There was a feeling,” wrote Bradley, “that MacArthur had been ‘kicked upstairs’ to chairman of the board and was, insofar as military operations were concerned, mainly a prima donna figurehead who had to be tolerated.”103 MacArthur had become what he feared most: ignored and irrelevant. He was stung by public criticisms characterizing his actions in Korea as “a momentous blunder,” a “gross miscalculation,” and a “great tragedy.”104 As the war in Korea stabilized in January 1951, MacArthur had probably already decided that he would challenge the president in order to regain the influence and power he had lost after the Inch’ŏn landing. He would gamble his career and reputation in a public spat with the increasingly unpopular Truman administration to redeem his honor and kick-start a new career in politics. It was a calculated risk and one that only MacArthur, courageous, flamboyant, brilliant, but supremely egotistical, could have taken.

On January 14, Mao cabled Peng his estimate on the future intentions of the UN forces: they could, under pressure from the CPV and NKPA, retreat from the peninsula after “symbolic” resistance; or they could retreat to Taegu and Pusan, wage a stubborn defense as in 1950, and then retreat. Either way, Mao thought, “they will finally retreat from Korea after we have exhausted their potential.”105 It was now Mao’s turn to underestimate the enemy. His drastic miscalculation about American tenacity and its ability to spring back from defeat cost the Chinese the opportunity to gain a greater victory at far less cost than what they would get later, after another two and a half years of war. The success of the third offensive, and especially the recapture of Seoul, had convinced Mao that China now held the upper hand. China’s victories, just like MacArthur’s success at Inch’ŏn, had made Mao hungry for total victory in Korea. This overconfidence led him to reject the UN Cease-Fire Commission’s peace plan, which included many of Beijing’s earlier demands. Presented to the UN on January 11, the plan proposed a five-step program: (1) cease-fire; (2) a political meeting for restoring peace; (3) a withdrawal by stages of all foreign forces; (4) arrangement for an immediate administration of all Korea; and (5) an establishment of an “appropriate body” composed of the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China to settle Far East problems, including the status of Taiwan and China’s representation in the UN.

This was a poor deal for Washington, for the “appropriate body” charged with settling affairs in Korea was clearly stacked against the United States. The United Kingdom was likely to support a motion to seat the PRC instead of Taiwan in China’s seat at the UN, as it had promoted such a shift since the founding of the PRC. China’s admission to the UN would lead to a complete loss of UN support for Taiwan. This would not play well domestically, since the Truman administration was already under fire for having “lost” China, and the “primitives” were getting louder in their calls for Acheson’s head. The cease-fire, proposed to take place at the 37th parallel, therefore farther south than the 38th, would also yield considerable new territory to North Korea, including Seoul. South Koreans would undoubtedly oppose it bitterly. Acheson recalled, “The choice whether to support or oppose this plan was a murderous one threatening, on the one side, the loss of the Koreans and the fury of Congress and press and, on the other, the loss of our majority and support in the United Nations.” Nevertheless, Acheson decided to gamble by recommending support, calculating that the Chinese would reject it. After painful deliberations, Truman supported the recommendation. Acheson later wrote, “The President—bless him—supported me even this anguishing decision.”106 As Acheson and Truman “held their breath,” the Chinese unequivocally rejected the UN cease-fire plan. Acheson’s gamble, which he admitted had almost brought the administration to “the verge of destruction domestically,” had paid off.107

With China’s rejection of the cease-fire, Washington could claim the moral high ground, for it was China’s decision to continue the war. On January 20, a resolution condemning China as an aggressor was introduced in the UN. Britain and other allies thought the condemnation of China was gratuitous, but Acheson, with an eye toward American public opinion, lobbied unapologetically for the resolution.108 It was a triumph of poker-player diplomacy and Acheson had played his cards beautifully. China was now thrust into a pariah status as an aggressor, while the Truman administration suffered little domestic political consequences. Getting the British to support the resolution had been a particularly hard sell, but with Acheson’s private assurances that the administration would not use the resolution as an excuse to widen the war, the British finally agreed. The UN General Assembly resolution condemning China passed on February 1.

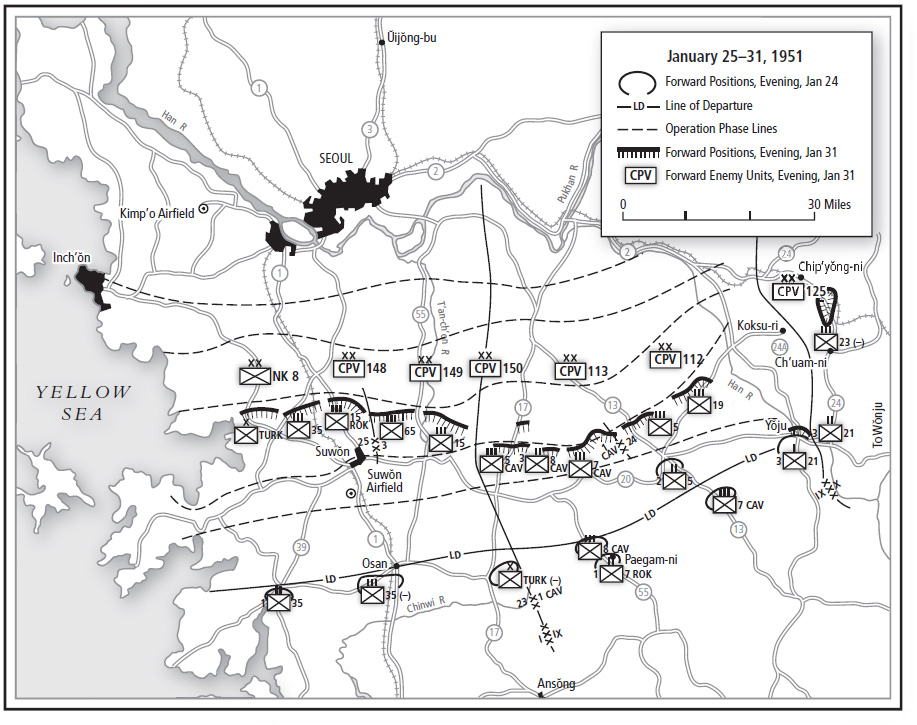

Meanwhile in Korea, Ridgway was taking his own great gamble. He launched a probe in mid-January to find the CPV, which seemed to have disappeared. He was wary of a possible trap and repeating the mistake of November, when MacArthur recklessly urged an advance to the Yalu. There were other concerns as well. The Russians had greatly built up the Chinese air force in recent weeks. By January 1951, some estimates gave the Chinese as many as 650 combat aircraft.109 The question on everyone’s mind was whether this new airpower would be used against UN forces. Ridgway considered two options: dig in and wait for the Chinese to make their next move, or take the initiative and go on the offensive. Unsurprisingly, Ridgway chose to go on the offensive, even though the Eighth Army was not completely recovered. Run right, his plan would have an incalculable psychological benefit. He needed to show his soldiers, and the badly mauled ROK forces, that the Eighth Army was no longer in retreat. He also desperately needed to know about the enemy: “There were supposed to be 174,000 Chinese in front of us at that time but where they were placed, in what state of mind, and even that they were there at all was something we could not determine. All our vigorous patrolling, all our constant air reconnaissance had failed to locate any trace of this enormous force.”110

Ridgway’s probe discovered the Chinese withdrawing. Furthermore, the feared Soviet-backed Chinese air force had failed to materialize. Ridgway’s actions made clear to Mao and Kim that Peng’s calculation had been correct: the UN forces were not defeated nor would they withdraw from the peninsula without a fight. Thus, by the end of January 1951, the communists’ euphoria about the war began to decline sharply. While tensions between America and its allies, and especially with Britain, had eased significantly by early 1951, relations between Stalin and Mao were strained. Mao realized that Stalin was doing his utmost to keep the Soviet Union out of direct participation in the war.111

On January 25, Ridgway launched a general offensive that caught Peng by surprise. Peng reported on February 4, “We are obliged to begin the 4th phase of operations. The battle begins under unfavorable conditions. Our period of rest is interrupted and now, when we are not yet ready to fight.”112 The fourth phase of the Chinese offensive might have been forced to be launched prematurely, but at least the UN forces did not know where the attack would come.

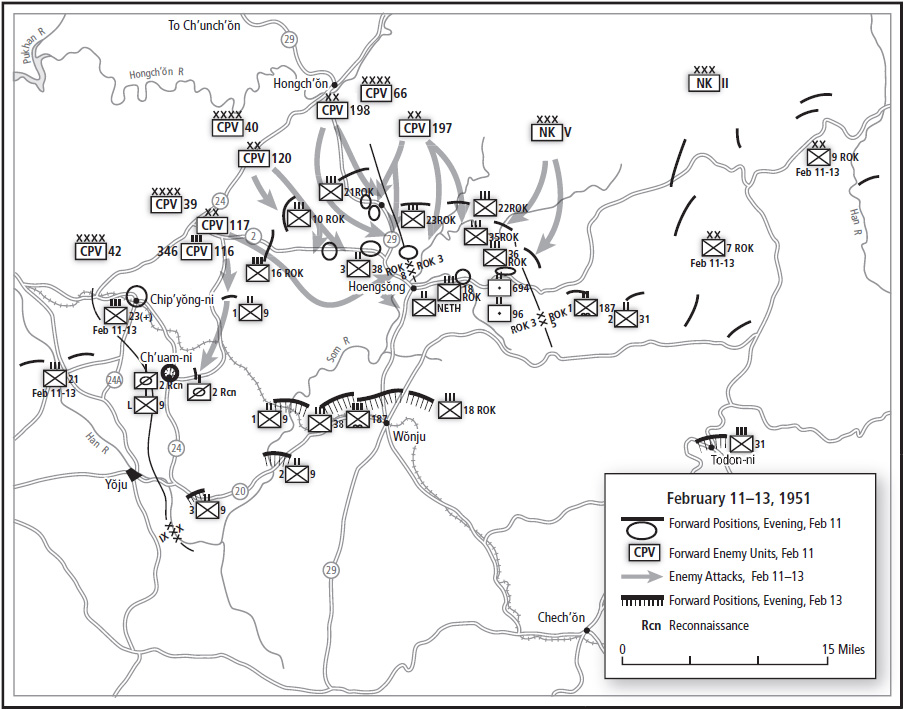

By early February, the Eighth Army had reestablished full contact with the CPV, but it did not know if the Chinese were establishing a defensive line or preparing a counteroffensive, and if so, where. Intelligence indicated that Chinese forces had shifted from the west to the mountainous central region. Ridgway could not be sure where the Chinese might strike along this central region, but the most likely path of enemy advance would be down the Han River valley toward Wŏnju. Chinese control of Wŏnju would allow them to be within striking distance of Taegu. And once Taegu was taken, the Chinese would be poised to take Pusan. Major action was anticipated for the X Corps, which was deployed in the central region.113 Ridgway was thus prepared to go to the defensive, taking advantage of the rugged terrain in the central region. His objective was “to advance and then hold along the general line Yangp’yŏng-Hoengsŏng-Kangŭng” from west to east. Ridgway intended to dig in behind this defensive line and slaughter Chinese forces during their attempt to cross it.114

First phase of the UN counteroffensive, January 25–February 11, 1951. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

On February 5, the X Corps launched its offensive. The attack plan was to move about thirteen miles north of Hoengsŏng to Hongch’ŏn to disrupt North Korean forces that could threaten the X Corps. Almond’s plan of advance placed the lightly armed and weaker ROK divisions of his command in the lead, followed by the heavier American units. The result of this disposition proved to be disastrous. On February 11, three CPV divisions hit the ROK Eighth Division in a frontal assault in broad daylight and destroyed it within hours. Its collapse imperiled the U.S. Second Infantry Division at Hoengsŏng. “Our people fought desperately to extricate themselves from certain destruction,” recalled one veteran. “On the afternoon of February 13, I received an order to proceed [south] to Wŏnju immediately. Upon my arrival late in the day, I was informed of the catastrophe suffered by our people and the expectation that the Chinese would resume their attack the next morning.”115 A tally of casualties a few days later revealed a disastrous outcome: over 1,500 Americans and Dutch (the Netherlands Battalion was attached to the Second Division) killed, wounded, and missing and nearly 8,000 casualties for the ROK Eighth Division.116 UN losses at Hoengsŏng were so appalling that MacArthur’s headquarters (Far East Command) tried to suppress the story. When the Seventh Marines passed through the same area later in March, they were shocked to discover corpses still littering the battlefield. It was, recalled Bill Merrick, “like an enormous graveyard.”117 More than 250 bodies of American and Dutch soldiers, including the Dutch battalion commander, Marinus den Ouden, were recovered. Many of the bodies had been looted of shoes and clothes, and several had been bound and shot in the back. Sickened by the sight, the marines erected this sign:

MASSACRE VALLEY.

SCENE OF HARRY TRUMAN’S POLICE ACTION.

NICE GOING, HARRY.