By the end of February 1951, the Eighth Army was again on the offensive and advancing steadily. On March 15, Seoul, now a devastated city, was abandoned by the enemy without a fight, and changed hands for the fourth time in less than nine months. Unlike the festive mood that had surrounded the recapture of the city in September, there were no ceremonies and no grand speeches to mark the occasion. The ROK troops who first entered the city simply took down the North Korean flag and raised their own at the Capitol Building. The war-beaten residents appeared almost too weary to notice. Soon, the issue of whether to cross the 38th parallel once again became a matter of discussion. The political and military situation was entirely different from what it was in September 1950. The kind of sustained drive into North Korean territory after Inch’ŏn appeared unlikely against the still-formidable Chinese force. Nevertheless, MacArthur pressed for unifying the peninsula and taking the war to China. On February 15, he asked for the removal of military restrictions, to permit bombings to disrupt the supply line from the Soviet Union into North Korea. The JCS denied the request. On February 26, MacArthur asked for authorization to bomb the hydroelectrical power facilities along the Yalu. The JCS did not give it to him, for “political reasons.” A frustrated MacArthur issued a public statement on March 7, in direct violation of Truman’s gag order on public discussion of policy matters, predicting that the “savage slaughter” would continue and the war would evolve into one of attrition and indecisiveness unless Washington’s policies changed.

The first opportunity to bring an end to the war came in March when the exhausted Chinese forces abandoned Seoul and retreated north, allowing the UN forces back to the 38th parallel. With status quo ante bellum essentially restored, the UNC, as George Kennan had predicted, was finally in a position to negotiate a settlement from “something approaching an equality of strength.” On March 20, the Joint Chiefs informed MacArthur that the president was about to implement a peace initiative: “Strong UN feeling persists that further diplomatic efforts towards settlement should be made before any advance with major forces north of 38th parallel,” they wrote. “Time will be required to determine diplomatic reactions and permit new negotiations that may develop.” Rather than responding directly to the initiative, MacArthur simply reiterated his earlier position: “I recommend that no further military restrictions be imposed upon the United Nations Command in Korea … The military disadvantages arising from restrictions … coupled with the disparity between the size of our command and the enemy ground potential render it completely impracticable to attempt to clear North Korea or to make any appreciable effort to that end.” The JCS was puzzled by the cable. His “brilliant but brittle mind” seemed to have snapped, recalled Bradley, but no one in Washington was prepared for what MacArthur did next.1

On March 24, MacArthur issued a public statement that challenged the pride of China and the authority of his Washington superiors, sabotaging any chance for a peace settlement. MacArthur’s “communiqué” began by taunting China for its lack of industrial power and poor military showing against UN forces. More seriously, he raised the possibility of a widened war: “The enemy, therefore, must by now be painfully aware that a decision of the United Nations to depart from its tolerant effort to contain the war to the area of Korea, through an expansion of our military operations to his coastal areas and interior bases, would doom Red China to the risk of imminent military collapse.”2 He concluded with words that seemed calculated to upstage the president: he, MacArthur, personally “stood ready at any time” to meet with the Chinese commander for a settlement. The White House and the State Department were bombarded with queries by allied leaders and the press demanding to know whether there was now a new direction in U.S. policy in Korea. The French newspaper Le Figaro mocked MacArthur’s negotiation offer as “an olive branch with a bayonet hidden amongst the leaves.” London’s Daily Telegraph observed that “the U.N. General Assembly becomes embarrassed, resentful or merely incredulous when General MacArthur … speaks again of carrying the war to the Chinese mainland.” Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Vyshinsky probably best summed up the general reaction of the foreign press when he announced that MacArthur was “a maniac, the principal culprit, the evil genius” of the war.3

That evening, Deputy Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, Dean Rusk, and others gathered at Acheson’s home to discuss the uproar that MacArthur had created. Lovett, Acheson recalled, “was angrier than I had ever seen him.” The general, he said, “must be removed at once.” Acheson shared Lovett’s anger: “[MacArthur’s statement] can be described only as defiance of the JCS, sabotage of an operation of which he had been informed, and insubordination of the grossest sort to his Commander-in-Chief.” The following day, Lovett, Acheson, and Rusk met with Truman. “The President,” recalled Acheson, “although perfectly calm, appeared to be in a state of mind that combined disbelief with controlled fury.”4 In his memoirs, Truman confided that he decided that day to relieve MacArthur, although it was not yet clear to him when and how he would do it. “[MacArthur’s statement] was an act totally disregarding all directives to abstain from any declarations on foreign policy … By this act MacArthur left me no choice. I could no longer tolerate his insubordination.” Yet, despite the seething anger in the room, the president coolly asked the group to check his directive prohibiting comments on policy to see if there was any ambiguity. They told him it was crystal clear. Truman then instructed Lovett to send a priority message to MacArthur “that would remind him of his duty under the order.”5 Given the circumstances, Truman’s mild reprimand appeared to be yet another instance of Washington’s leaders caving in to MacArthur. The general had, after all, violated the December order repeatedly, including his statement earlier in March predicting a “savage slaughter” in Korea, and nothing much was said then. Despite his “controlled fury,” Truman appeared to be wavering again.

However, it was different this time. Truman’s outward restraint was due to not only his sense of caution, but also what others called “political guile.” As during other crises, Truman refused “to act impulsively or irresponsibly, whatever his own feelings.”6 His ability to remain cool, calm, and collected under fire was a trait that his staff had come to admire.7 On this occasion, there was an additional motive. For all his anger, Truman understood that MacArthur remained an enormously popular figure. The mood of the country favored the general, not the president. A mid-March Gallup poll showed the president’s public approval rating at an all-time low of just 26 percent. War casualty figures were appalling and further soured the national mood (the Defense Department reported that the United States had suffered a total of 57,120 casualties since June 1950).8 People were becoming fed up with the war, and MacArthur at least spoke of a way to victory and end. Patience was required to bring down MacArthur. Premature or rash action would hurt only Truman and his administration. Thus, far from being timid, Truman’s calm rebuke was actually a calculated response aimed, in Acheson’s words, at “laying the foundation for a court-martial.”9

Truman did not have to wait long. In early April, House Minority Leader Joe Martin took the floor with an explosive revelation. A longtime MacArthur admirer, Martin told the House that he had sent the general a copy of a speech he had made in February. Martin called for the use of Nationalist Chinese forces in Korea and accused the administration of a defeatist policy. He asked for MacArthur’s views “to make sure my views were not in conflict with what was best for America.”10 MacArthur’s response carried no stipulation of confidentiality, and Martin announced it dramatically in Congress: “It seems strangely difficult for some to realize that here in Asia is where the Communist conspirators have elected to make their play for global conquest, and that we have joined the issue thus raised on the battlefield … if we lose the war to communism in Asia the fall of Europe is inevitable, win it and Europe most probably would avoid war and yet preserve freedom.”11

The Martin letter and renewed doubts about MacArthur’s loyalty could not have come at a more inopportune time. The Joint Chiefs had just received alarming intelligence that the Soviet Union was preparing for a major military move. “One suggestion,” recalled Bradley, “taken with utmost seriousness, was that they would intervene in Korea. Another was that they might attempt to overrun Western Europe.”12 It appeared that the situation in Korea had reached a new crisis point. In conveying these reports to Truman, Bradley also provided the JCS’s recommendation that MacArthur be authorized to retaliate against air bases and aircraft in China in the event of a “major attack.”13 He convinced Truman that the Chinese and the Russians might be preparing to push the United States out of Korea and that the air force needed to be prepared to respond quickly. Deeply shaken, Truman called for the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Gordon Dean, who controlled all nuclear warheads, and told him that he had decided to deploy bombers and atomic warheads to the Pacific because of the serious situation in Korea.14 Dean recalled, “He [Truman] said that if I saw no objection, he would sign the order directing me to release to the custody of General Vandenberg, Chief of Staff, USAF, nine nuclear ****[sic].”15 Truman said that he was not giving the air force a green light to drop the nuclear bombs; he still hoped the need to use them would never arise. He was sending them as a contingency, and no decision would be made without consulting the National Security Council’s special committee on atomic energy. The next day, the 99th Medium Bomb Wing was ordered to pick up atomic bombs for trans-shipment to Guam. By this time, Truman and Acheson had approved a draft order to MacArthur authorizing him, in the event of a “major” air attack on UN forces originating outside of Korea, to retaliate against air bases in China, but not with nuclear weapons without Truman’s release.

MacArthur never received the order. Bradley later explained, “I was now so wary of MacArthur that I deliberately withheld the message and all knowledge of its existence from him, fearing that he might, as I wrote at the time, ‘make a premature decision in carrying it out.’”16 MacArthur had lost Bradley’s trust. By sending nuclear bombs and approving a directive that conditionally authorized their use, Truman strengthened the argument for MacArthur’s relief: if nuclear weapons were to be used in Korea, it was absolutely essential to have a trustworthy commander in the field. Furthermore, Truman had shown that although he disapproved of MacArthur’s public statements, he was willing to consider the strategic concepts underlying them.17 While Truman and the JCS were in agreement with MacArthur on what had to be done in case of an attack, they were also in agreement that MacArthur was the wrong person to be entrusted with such a difficult mission.18 It was this confluence of events—MacArthur’s letter to Martin, the crisis in Korea, and the decision to deploy nuclear weapons—that led to the conclusion to dismiss MacArthur. Acheson, Bradley, George Marshall, and Averell Harriman (the “Big Four”) unanimously agreed that MacArthur should be relieved of duty.19

Truman insisted that MacArthur be notified with courtesy and dignity. Secretary of the Army Frank Pace Jr. was en route to Japan and Korea, and Marshall decided to have him deliver the order of relief personally to MacArthur on the morning of April 12 (evening of April 11, Washington time) before it was publicly announced. But a chain of actions made the notification neither courteous nor dignified. On the evening of April 10, the information had leaked, and the Chicago Tribune, a staunch critic of the Truman administration, queried for confirmation and details. An emergency White House meeting considered whether to stick to the original plan or to make an immediate announcement. The fear was that the Tribune would notify MacArthur, and he might try to trump the president by dramatically resigning before the public announcement. The risk could not be taken. A special press conference was called at 1:00 am on April 11, Washington time, to tell the reporters, bleary-eyed and bewildered, of the extraordinary news. Although an attempt was made to inform MacArthur shortly before the press conference, radio broadcast of the order reached Tokyo first.20 MacArthur learned of his dismissal from his wife, Jean, after she was notified by a member of the personal staff who had heard the news on the radio. MacArthur was seventy-one years old and had been in Asia for fourteen years. Ridgway was chosen to replace him.

Ridgway did not know of his promotion until a reporter congratulated him. Flustered, the general shrugged it off. Not long thereafter, he received official word from Secretary Pace and the next day flew to Japan for his last meeting with MacArthur. Ridgway recollected, “He was entirely himself, composed, quiet, temperate, friendly, and helpful to the man who was to succeed him.”21 Nevertheless, MacArthur’s rancor against Truman was palpable. He told Ridgway that an “eminent medical man” had confided to him that “the President was suffering from malignant hypertension” and that “this affliction was characterized by bewilderment and confusion of thought.” Truman, MacArthur declared, “would be dead in six months.”22

MacArthur left Tokyo amid much emotional fanfare. The Japanese Diet passed a resolution praising him. Prime Minister Yoshida and other top officials publicly expressed their gratitude for his “outstanding” service to Japan. Throngs of Japanese densely lined the route from the embassy to the airport to offer their farewells. A nineteen-gun salute was rendered and a large formation of jet fighters flew in formation over the airport in his honor.23 “The farewells were an ordeal,” commented William Sebald, the American ambassador to Japan. “Many of the women were sobbing openly, and a number of the battle-hardened men had difficulty suppressing their tears.”24 MacArthur turned and waved to the crowd one last time before boarding his famed Bataan. “You’d think he was a conquering hero,” said one observer, “not at all a demeanor of a man who’d just been fired.”25

MacArthur received a tumultuous reception on his return to the United States. It was his first visit to the continental United States in fourteen years. He was greeted with one of the biggest ticker-tape parades ever staged in New York, and he delivered a stirring farewell speech to a joint session of Congress that Congressman Dewy Short of Missouri characterized as “the voice of God.”26 The reaction to MacArthur’s firing was stupendous. In San Gabriel, California, students hanged an effigy of Truman. In Ponca City, Oklahoma, a dummy representing Acheson was soaked in oil and then burned. At MacArthur’s birthplace in Little Rock, Arkansas, citizens lowered the flags to half mast. In Lafayette, Indiana, workers carrying signs “Impeach Truman” paraded in the rain. Senator Richard Nixon from California reported that he had received more than six hundred telegrams on the first day of the news of MacArthur’s recall, and most were in favor of impeachment of Truman. “It is the largest spontaneous reaction I’ve ever seen,” said Nixon, who demanded MacArthur’s immediate reinstatement. Before the day was over, the White House had received seventeen hundred telegrams about MacArthur, three to one against his removal.27 Republicans spoke threateningly of “impeaching” the president. Pro-administration voices, however, were heard in the two houses of Congress, both controlled by the Democrats, Truman’s party. House Speaker Sam Rayburn spoke for many of the president’s supporters when he declared, “We must never give up [the principle] that the military is subject to and under the control of the civilian administration.”28

Japanese crowds line the road to the airport to say good-bye to General MacArthur, April 16, 1951. (U.S. ARMY MILITARY HISTORY INSTITUTE)

“Bon Voyage” and “God Be with You” from Japanese well-wishers, April 16, 1951. (U.S. ARMY MILITARY HISTORY INSTITUTE)

Throughout Europe, MacArthur’s dismissal was greeted as welcome news, as the Europeans had long feared his mercurial ambition and desire to widen the war. “The removal of MacArthur will be received with dry eyes; yes with extraordinary relief,” reported the Danish newspaper Afterbladet, which described Truman’s decision as “the most daring during his career.” The French, reported Janet Flanner in The New Yorker, were “solidly with Truman.” Britain’s Conservative leader Winston Churchill expressed his approval, stating that “constitutional authority should control the action of military commanders.” Ironically, the Russians and the Chinese also approved. But the most impressive support for Truman’s decision was the weight of editorial opinion at home. The New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Atlanta Journal, Minneapolis Tribune, and Christian Science Monitor all endorsed his decision. Truman remained calm throughout the political storm because, as he later confided, “I knew that once all the hullabaloo died down, people would see what he was.” As he anticipated, the “hullabaloo” did subside. After Senate hearings investigating MacArthur’s dismissal had shown that Truman’s decision to relieve the general had been unanimously backed by Secretary of Defense Marshall and the JCS, public opinion turned in favor of the president. In mid-May, Democratic National Committee Chairman William Boyle pronounced that “the public ‘furor’ over MacArthur’s dismissal appeared to be subsiding,” and that the Senate hearings had “helped to blow away much of the fog and bring out the facts.”29

While the Truman administration settled on limiting the war, the Chinese decided to make one last effort to drive UN forces out of the peninsula. Although the defeats at Wŏnju and Chipyŏng-ni had demonstrated that a quick victory would be elusive, Mao believed that success was possible with sufficient forces. He thought a million men could do it. This was nearly three times the number of soldiers who had pushed back the UN forces the previous fall and winter.30 The spring offensive from mid-April to mid-May 1951 would be the last effort for a communist victory and the largest campaign of the Korean War. Peng had reservations about the logistical capacity to support such a massive offensive, but he agreed with the plan, believing that it was more favorable for the CPV to fight now than later, because “the enemy is tired, its troops have not been replenished, its reinforcements have yet to gather, and its military strength is relatively weak.”31 By launching the spring offensive, the CPV could “regain the initiative.”32

Lieutenant General James Van Fleet replaced Ridgway as the commander of the Eighth Army just before the spring offensive was launched. Only days after taking over, he would be in charge of defending against the massive communist assault. Van Fleet was coming off a highly successful assignment in Greece. In the post–World War II period, Greece had become fertile ground for communism. With Moscow’s support, Greek communists initiated an insurgency. At first, Britain provided military and economic assistance, but by early 1947 the British had run out of resources, bankrupted by World War II, the loss of colonies, and the crisis it supported in Europe. Britain asked the United States to accept responsibility for continuing the aid, and it did, thus establishing the Truman Doctrine in March 1947 that committed the United States to help fight communism around the globe. Van Fleet arrived in Greece in late February 1948 to revamp the Greek army, which, among other things, “lacked an offensive spirit” and was shot through with “incompetent older officers.”33 He did such a remarkable job that by August 1949 the Greek army was able to put the communist insurgents on the run. It was a great victory for the Truman Doctrine and a personal triumph for Van Fleet.

Truman and others saw the situations in Korea and Greece as similar, and so it was thought that Van Fleet’s success in Greece might be replicated in Korea. Both countries were poor, peninsular with mountainous terrain, and wracked by a brutal civil war with communists who were supported by border states (Soviet support for the Greek communists had been channeled through Yugoslavia, although Tito’s split from Stalin closed this route and was a major factor in the defeat of the insurgency). The long-term solution for Korea, like Greece, was thought to be the creation of reliable and effective indigenous security forces that could stand up to the communist threat. Bittman Barth, who served under Van Fleet in France in 1944, recalled that Van Fleet inspired his men with “quiet self-assurance” that transmitted “a feeling of confidence.” The Greeks “admired him tremendously,” as would the South Koreans, who later honored him with the epitaph “Father of the ROK Army.”34

Ridgway told Van Fleet, when he arrived on April 14, that although he would give Van Fleet “the latitude and high respect his ability merited,” he would keep a tight rein on operations in Korea: “I undertook to place reasonable restrictions on the advances of the Eighth and ROK Armies. Specifically, I charged Van Fleet to conduct no operations in force beyond the Wyoming Line [the farthest line of advance of UN forces, located slightly north of the 38th parallel] without prior approval of GHQ. I made my wishes unmistakably clear to General Van Fleet with respect to the tactical latitude within which he was to operate.”35 Ridgway’s decision to closely oversee Eighth Army operations was warranted because he was concerned that Van Fleet might share MacArthur’s view on the war and might, perhaps inadvertently, initiate actions that could widen it. One of Ridgway’s first official acts as the new head of Far East Command was to issue a “directive” to his senior commanders that succinctly laid out the basic principles on which the war was to be waged to support the UN and U.S. policy for limiting the war:

The grave and ever present danger that the conduct of our current operations may result in the extension of hostilities, and so lead to a worldwide conflagration, places a heavy responsibility upon all elements of this Command, but particularly upon those capable of offensive action. In accomplishing our assigned missions, this responsibility is ever present. It is a responsibility not only to superior authority in the direct command chain, but inescapably to the American people. It can be discharged ONLY if every Commander is fully alive to the possible consequences of his acts; if every Commander has imbued his Command with a like sense of responsibility for its acts; has set up, and by frequent tests, has satisfied himself of the effectiveness of his machinery for insuring his control of the offensive actions of his command and of its reactions to enemy action; and, in final analysis, is himself determined that no act of his Command shall bring about an extension of the present conflict … International tensions within and bearing upon this Theater have created acute danger of World War III. Instructions from higher authority reflect the intense determination of our people, and of all the free peoples of the world, to prevent this catastrophe, if that can be done without appeasement, or sacrifice of principle.36

Ridgway also issued a more specific “Letter of Instructions” to Van Fleet designed “to prevent expansion of the Korean conflict.” He instructed Van Fleet that “your mission is to repel aggression against so much of the territory (and the people therein) of the Republic of Korea, as you now occupy and, in collaboration with the Government of the Republic of Korea, to establish and maintain order in said territory … Acquisition of terrain in itself is of little or no value.”37 Bradley later wrote, “It was a great relief to finally have a man in Tokyo who was in agreement with the administration’s views on containing the war.”38

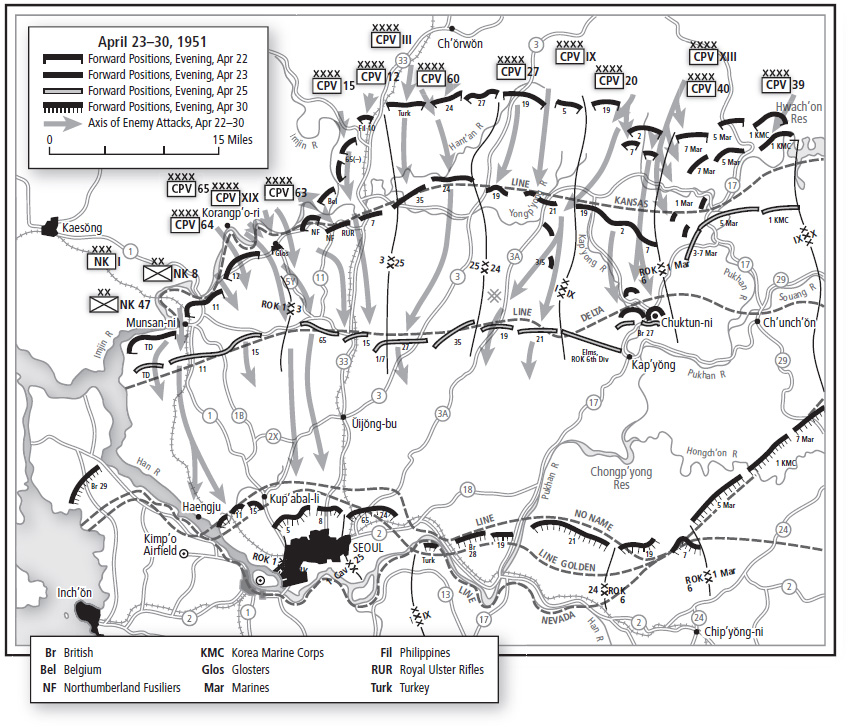

The spring offensive was launched on April 22, just eight days after Van Fleet’s arrival. The communist forces struck in two tremendous and simultaneous blows: a main effort in the west by Chinese troops and a supporting attack in the east, through rugged mountains, by the North Koreans. In the west, 250,000 Chinese attacked the I and IX Corps with the aim of capturing Seoul by May 1. Most of the units of the two corps were American, but I Corps also included the Twenty-Ninth British Brigade, and each corps had an ROK division, which, given its weaker strength, proved to be an Achilles’ heel. The ROK Sixth Division in the IX Corps was overwhelmed and collapsed, threatening the U.S. Twenty-Fourth Division to its west and the First Marine Division to its east with envelopment. The collapse of the ROK Sixth Division symbolized for many, then and since, the weakness of the ROK Army. Some blamed the inadequacy of the unit’s weaponry and training against overwhelming Chinese force, but many others blamed poor leadership and cowardice. It was an ignoble fate for a division whom some credited for having saved the nation by mounting an effective and stubborn defense in the Ch’unch’ŏn area in the opening days of the war, an action that threw off the North Korean schedule and bought time for UN forces to arrive.

The First Marine Division, with an exposed flank, was forced to fall back. The U.S. Twenty-Fourth Division’s exposed eastern flank posed an even more serious challenge. It appeared that the Chinese plan was a wide envelopment of Seoul from the east in concert with the main thrust from the north. Fortunately, the Twenty-Seventh Commonwealth Infantry Brigade, consisting of British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, and Indian units, made a heroic stand at Kapyŏng and checked the eastern arm of the offensive. In the west, the Chinese attack concentrated on the weakest part of the front line, the sector held by the ROK First Division occupying the westernmost end. To its eastern flank was the British 29th Infantry Brigade. These forces held the gates to Seoul, and if they collapsed, not only Seoul but the entire front would be in danger of being rolled up.

Chinese spring offensive, April 22–30, 1951. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

The capture of Seoul seemed to be the communists’ main objective. Though Ridgway had not changed his view about not holding real estate just for its own sake, he believed that for psychological and symbolic reasons, Seoul had become an overwhelming stake for Mao, especially after the defeats at Wŏnju and Chipyŏng-ni. Ridgway instructed Van Fleet to make a strong stand for Seoul: “I attach considerable importance to the retention of Seoul. Now that we have it, it is of considerable more value, psychologically, than its acquisition was when we were south of the Han.”39 Van Fleet agreed and thought that losing the capital would also have a deleterious effect on ROK forces. “Seoul had been given up twice before,” Van Fleet later recalled. “I felt that to give it up a third time would take the spirit out of a [Korean] nation. It would destroy morale completely to lose their capital.”40 The war devolved to a battle for Seoul. Given the CPV’s logistical shortcomings, Van Fleet estimated that holding them up for several days north of Seoul with delaying or blocking actions would be sufficient to exhaust their supplies and give the UN force enough time to establish a strong defensive line. This critical mission largely fell on the British 29th Brigade with its attached Belgian battalion. It was deployed widely along the Imjin River at the most traditional crossing point, where armies had swept north and south through the peninsula over the past centuries. It was no different this time, as the main thrust of the Chinese pointed at the heart of the brigade. Due to the wide front that the British and Belgians had to hold, the line was not continuous, islands of companies being separated by wide-open stretches. Holding back the Chinese main assault would be a difficult if not an impossible task.

The British 29th Brigade had arrived in Korea in early November 1950, just in time to be initiated into the war with the Chinese intervention and the UN retreat. As with all British formations, its units possessed long and proud martial histories, going back as far as the seventeenth century, and had served in some of the most storied and exotic corners of the British Empire. Many of the soldiers were reservists who had been in World War II, and at an average age of thirty, many were married with children when they were called back to duty. The Belgian battalion with its Luxembourg platoon was attached to the brigade on the eve of the battle at Imjin River.

The Chinese struck on the night of April 22. In the initial assault, the Belgian battalion was surrounded and cut off. For twenty-four hours the Belgians’ situation was precarious, but they held off the Chinese until they could be rescued and fall back. The next day, two British battalions, the Glosters (1st Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment) and the Royal Ulster Fusiliers, were besieged by Chinese forces. The incredible mobility of the Chinese on foot over the rough terrain enabled them to surround these units by infiltrating through the open stretches in the line. By mid-morning the battalions were forced to contract to hilltop perimeters. The Chinese also put terrific pressure on the ROK First Division, which was covering the British brigade’s western flank. While it did not collapse like the ROK Sixth Division, it was nevertheless driven back several miles, exposing the Glosters’ flank. The Glosters, anchoring the brigade’s western end, found themselves in considerable difficulty as the Chinese completed their encirclement. The battalion, having suffered many casualties, was tightly ensconced atop a single hill, Hill 235. Its commanding officer, Lt. Col. James Carne, inquired about a possible withdrawal before the noose became too tight. Brigadier Tom Brodie, the brigade commanding officer, told Carne to stay put and hold out for just a few more hours. “I understand the position quite clearly,” Carne replied. “What I must make clear to you is the fact that my command is no longer an effective fighting force. If it is required that we shall stay here, in spite of this, we shall continue to hold.”41

Brodie assured Carne that a rescue mission was on its way. By this time, however, the Chinese had penetrated so far behind the lines that a rescue mission was increasingly becoming unfeasible. Ammunition, food, water, and medical supplies were running dangerously short. The men were more thirsty than hungry. “The heat of the day and the loss of sweat in the march up to the night position made them thirsty, and there was no water,” recalled Capt. Anthony Farrar-Hockley, the battalion’s adjutant. Aerial resupply was attempted, but the perimeter was small and located atop a steep hill surrounded by the Chinese, making accurate air drops nearly impossible. One pilot asked if “there (was) any means of marking a dropping zone.” Farrar-Hockley said he felt like shouting over the radio, “Tell them to aim for a high rock with a lot of Chinese around it!” Many of the bundles rolled down the hillsides to the Chinese. Substantial air support was also committed, but it did not relieve the situation.42

Early on the morning of April 25, after nearly three days of intense fighting, the 29th Brigade received orders to withdraw. Carne explained the situation to his men and told them that the battalion could not carry on as a unit. He gave them the option of surrendering or fighting their way out as separate groups. All opted to make their way out. Three of the four companies along with the staff at battalion headquarters headed south directly toward the UN line. Very few made it through, and most of them were captured, including Carne. The fourth company’s commander, Capt. Mike Harvey, decided on a counterintuitive route and proceeded north. This took his men straight into the Chinese rear, where they were able to swing around to the west and then south toward the UN line. For the next few miles Harvey and his group did not encounter any Chinese. Adding to their good fortune, they were spotted by a UN aircraft, which began guiding them homeward through the hills. Suddenly, they came under heavy fire from the Chinese, but then they saw American tanks just ahead of them down the valley. As they raced toward the tanks, however, the Americans mistook them for Chinese and opened fire, killing six. Horrified, the aircraft pilot flew frantically over the tanks and dropped a note from the sky. Realizing their mistake, the Americans ceased their fire, and the Glosters rushed forward for cover behind the tanks. The Americans were heartsick over their mistake. The lieutenant in charge asked how many were killed. Captain Harvey did not want to make the Americans feel any worse than he had to, so he did not answer.43

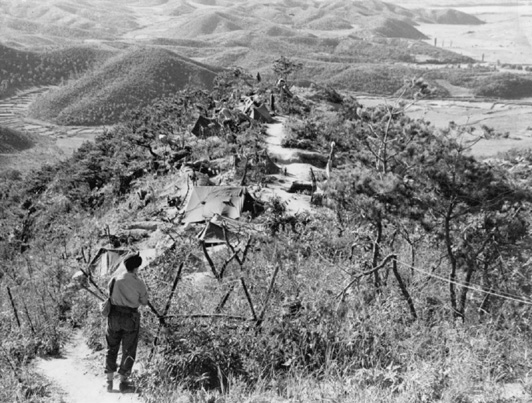

Top of Gloster Hill (Hill 235) shortly after the battle. (SOLDIERS OF GLOUCESTERSHIRE MUSEUM)

Of the original 699 men, only 77 made it out.44 A large number were captured and spent over two years in POW camps. Van Fleet described the Glosters’ action as “the most outstanding example of unit bravery in modern warfare.” Although there was much recrimination about who was responsible for the debacle—some blamed Brodie for not giving the withdrawal order earlier, while others blamed Carne for not communicating more clearly the dire situation—Van Fleet concluded that the loss of the Glosters had not been in vain: “This is one of those great occasions in combat which called for a determined stand,” he later wrote. “The loss of 622 officers and men saved many times that number.”45 The British 29th Brigade had held for sixty crucial hours, which had not only severely gutted the Chinese force but also seriously disrupted their schedule and momentum. It had also bought enough time to establish a firm defense line to protect Seoul. On the night of April 27–28, the Chinese made one final effort, but they were unable to overcome the defense line or sustain their attack. By April 29, there was a palpable diminution of the offensive. “After we had turned back the enemy’s first greatest onslaught by April 28,” recalled Van Fleet, “we dug in and waited for him to come. We waited and waited and he did not come.”46 Despite the huge losses, the Chinese had not yet given up hope. Turning their sights eastward, they planned a “second phase” of the spring offensive.

Glosters taken prisoner are on a break while on their way to a POW camp on the Yalu River. (SOLDIERS OF GLOUCESTERSHIRE MUSEUM)

Brigadier Tom Brodie, commander of the British 29th Brigade, unveiling a memorial to the men who lost their lives during the battle at Imjin River, July 5, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

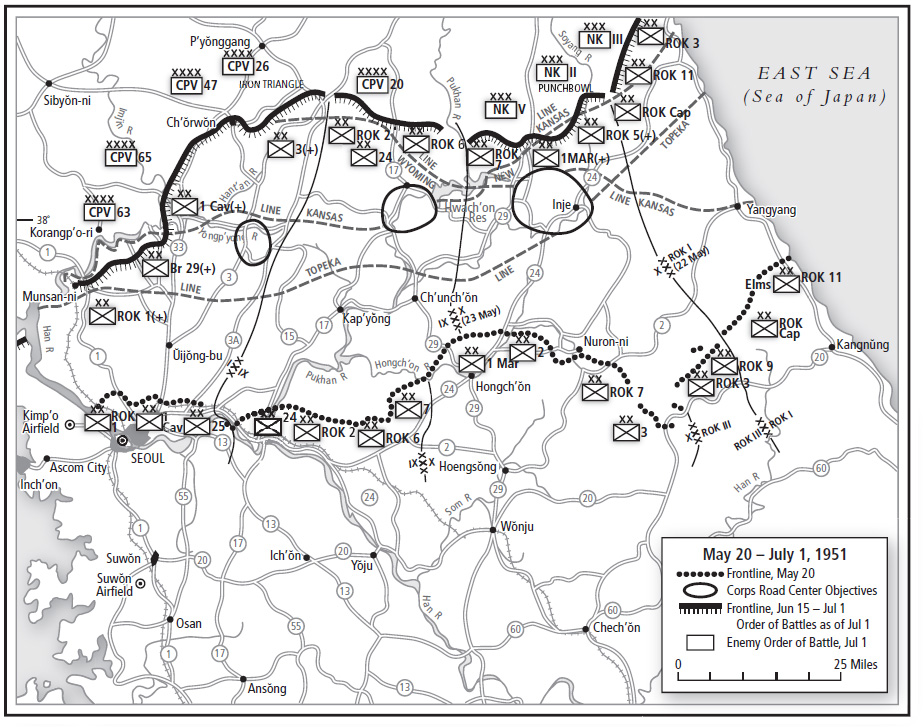

Detecting the CPV’s shift eastward, Van Fleet thought the Chinese were planning to attack down the Pukhan River valley to envelope Seoul from the southeast.47 Unexpectedly, the offensive was launched on May 16 much farther to the east than Van Fleet had estimated. Massive CPV and North Korean forces struck UN forces situated from the central region to the east coast. Van Fleet had placed his units mainly to defend Seoul and now faced an all-out attack on his weaker eastern sector. The main CPV effort was against X Corps and ROK III Corps, with a supporting attack against ROK I Corps deployed by the east coast. The four ROK divisions in X Corps and ROK III Corps rapidly collapsed. This exposed the U.S. Second Division’s right flank in a replay of the events of November 1950, when the collapse of the ROK Sixth Division placed the entire Second Division in a similar predicament that had led to its virtual destruction. The objective of the attack in the east was uncertain, but one possibility was to advance to Pusan. “This was a startling development,” recalled General Almond.48

The communist offensive met initial success, especially in the exploitation of the gap opened by the collapse of the ROK units. U.S. units to the west of the gap and ROK units from I Corps to the east were forced to fall back, creating a large bulge in the UN lines. But the shoulders held with rapid reinforcements and a shifting of forces from the western sector. Punishing artillery and air attacks exacted an enormous toll on the Chinese troops. By the third day, the offensive began to wane. Sensing the enemy’s exhaustion and with Ridgway’s urging, Van Fleet and Almond formed a counteroffensive plan that would, if successful, turn the game around and surround the bulk of the communist forces. IX Corps supported by I Corps would attack from the west and cut off lines of communication, supply, and, most importantly, reinforcement or withdrawal routes in the western half. X Corps, supported by ROK I Corps, would attack in the east to cut off similar lines in the eastern half. It was a bold plan nearly worthy of the Inch’ŏn operation in its ambition and objective. If successful, the entire eastern half of the front would be torn wide open, and a majority of the communist forces neutralized.

On May 20, merely four days after the communist offensive started, the western attack was initiated, joined by the eastern attack on May 23. Peng decided on May 21 to cut his horrendous losses and not only halt the offensive, but rapidly pull his forces back to a line about ten miles north of where they had started, because it was more defensible. The UN attacks were overly cautious and slow and allowed the bulk of the enemy to escape. By July 1, UN forces had pushed the communists back twenty-five to fifty miles north all across the front, establishing a line that more or less remained static for the next two years, until the armistice.

Despite the failure to completely destroy the attacking communist forces, the outcome was a triumph for the UN forces in general and the U.S. Army, and especially X Corps, in particular. During the opening days of the counteroffensive, wrote Van Fleet, UN forces “offered no resistance at all in the east or along the coast.” He concluded, “The Red soldier in that advance must have thought it was a very easy war.” However, on the third day, “we launched a counterattack in the main area of battle and instead of being outflanked by the Reds who had poured down the mountains and roads east for as much as 50 miles, we pinched them off and disposed of them at leisure.”49 Van Fleet had beaten the Chinese at their own game.

The success of the counteroffensive presented an opportunity to destroy the Chinese army and, by extension, a chance to win the war. Years later, Van Fleet would bitterly recall that the chance to end the war in May–June 1951 was squandered. This was not November 1950, when MacArthur had made his foolhardy plunge to the Yalu to face a fresh, strong, and eager Chinese army. After the huge casualties and deprivations suffered by the Chinese forces since the winter, Van Fleet believed they were tired, weak, and perhaps morally defeated. “The mission to which we had been assigned, to establish a defensive line across the peninsula, was accomplished,” recalled Van Fleet, “though we could have readily followed up our successes and defeated the enemy, but that was not the intention of Washington.”50 Sensing Van Fleet’s frustration, Ridgway wrote to him, “Because of this particularly sensitive period politically, I would like you and your most senior officers … meticulously to avoid all public statements about the Korean situation which pass beyond the purely military field.”51 Ridgway did not want another MacArthur-esque fiasco. Had the political will existed, a military victory might have been possible since the communist front lay wide open. “We met the attack and routed the enemy,” Van Fleet later wrote. “We had him beaten and could have destroyed his armies. Those days are the ones most vivid in my memory, great days when all of the Eighth Army, and we thought America too, were inspired to win.”52

Eighth Army advance, May 20–July 1, 1951. (MAP ADAPTED FROM MOSSMAN, EBB AND FLOW)

But Washington and its allies wanted only to bring the fighting to an end. No one could determine for sure what Mao would do if UN forces once again advanced to the Yalu. Surely, the Chinese forces would regroup and continue the fight. Then there was the issue of what Stalin might do if the war was extended to China. There was also little likelihood that North Korean communists would have simply accepted their defeat. Given the nature of the vicious civil war that preceded June 1950, disaffected Korean communists, northern and southern, would undoubtedly have taken up arms and continued the fight in an insurgency. With objectives to bring about “an end to the fighting, and a return to the status quo” achieved, Acheson told the Senate on June 7 that UN forces would accept an armistice. It was time to end the Korean War.