Secretary of State Dean Acheson was cautious but receptive to the overture for a cease-fire and an armistice from the Soviet ambassador to the UN, Yakov Malik, on June 23, 1951. There were doubts about the Soviets’ sincerity, but Acheson nonetheless responded quickly to seize an opportunity to end the fighting.1 General Ridgway was more skeptical. Although he found the prospect of a cease-fire “not unwelcomed,” he deeply distrusted the communists. He sent a message to “all commanders” in the field lest they began to let down their guards. “Two things should be recalled” about the Soviets, he warned: “One is the well-earned reputation for duplicity and dishonesty,” and “the other is the slowness with which deliberative bodies such as the [UN] Security Council produce positive action.” He cautioned General Van Fleet to “personally assure yourself that all elements of your command are made aware of the danger of such a relaxation of effort and that you insist on an intensification rather than a diminution of the United Nations’ action in this theater.”2

Ridgway was right to be cautious. In light of recent evidence, the Soviet proposal appears to have been disingenuous. In a cable to Mao in early June, Stalin stated that the best strategy to pursue was “a long and drawn out war in Korea.” By then, the Eighth Army’s successful counteroffensive had seriously disrupted the communist forces. A ceasefire would have been advantageous to the communists, as it would have allowed the Chinese and the North Koreans to rest and regroup. “The war in Korea should not be speeded up,” Stalin advised Mao, “a drawn out war, in the first place, gives the possibility to Chinese troops to study contemporary warfare on the field of battle and in the second place, shakes up the Truman regime in America and harms the military prestige of the Anglo-American troops.”3 Given the fighting and casualties suffered since October, the Chinese leadership probably thought they had learned enough. But Mao’s exchanges with Stalin indicate that he was willing to continue the war. His reaction to a potential end of hostilities appeared ambivalent.4 Although Mao responded favorably to an offer made by Ridgway, as the UNC commander, on June 29 to discuss an armistice, Mao’s message to Stalin two weeks earlier gave no indication that Mao was thinking about an armistice at all. “The position at the front in June will be such that our forces will be comparatively weaker than those of the enemy,” he wrote. “In July we will be stronger than in June, and in August we will be even stronger. We will be ready in August to make a stronger blow to the enemy.”5

In June, Mao’s intention was to use the operational pause during armistice negotiations to rebuild his forces and eventually resume the offensive, but his communications in July and August indicated that he was willing to conclude an armistice if it was accomplished in a manner that would not undermine China’s prestige.6 Mao was anxious to avoid unfavorable armistice terms that would threaten not only his leadership position, but the revolution itself. The Chinese regime was careful in how it presented the new strategy of ending the war to the Chinese people. On July 3, the Central Committee issued “Instructions on the Propaganda Affairs Concerning the Peace Negotiations in Korea,” which began with the point that “peace has been the very purpose of the CPV’s participation in the anti-aggression war in Korea.”7 The United States was to be portrayed as the weaker party, “that it was the American leadership who had solicited negotiations and an armistice” and not China.8 Mao already viewed the war as a victory for China: it had fought the world’s greatest superpower to a standstill, and he was not about to sabotage this perception. The British reporter and communist sympathizer Alan Winnington noted, “This is the first time Oriental Communists have ever sat down at a conference table on terms of equality with Americans, and they intend to make the most of it.”9

Ridgway had no interest in enhancing China’s or Mao’s prestige. He identified several points that he did not like in Beijing’s response accepting his June 29 proposal for a meeting to discuss an armistice. The most important clause was: “We agree to suspend military activities and to hold peace negotiations,” meaning, first stop fighting and then talk.10 In passing Beijing’s message to the JCS, Ridgway wrote that a suspension of military activities would “gravely prejudice the safety and security of UN forces” and would be “wholly unacceptable.” For their part, Chinese leaders believed that the fighting thus far had taught the Americans that neither side could achieve military victory, and therefore assumed that suspension of fighting and restoration of the 38th parallel as the border would be acceptable.11

Both sides had valid concerns. But whereas Mao was seeking ways to preserve and enhance China’s and his prestige, using the armistice negotiations with the world’s most powerful nation for domestic propaganda purposes, Ridgway had no intention of compromising on anything. Why should he yield anything to the Chinese when the UN forces were strong and had the advantage? When armistice negotiations started in July, Ridgway told the UN team’s chief delegate, Vice Adm. C. Turner Joy, that the basic UN position was an “implacable opposition to communism.” In his “Guidance Memo,” Ridgway instructed the delegates that they were “to lead from strength not weakness.” Ridgway concluded that if UN negotiators could “cap the military defeat of the Communists in Korea” with skillful handling of the armistice talks, “history may record that communist military aggression reached its high water mark in Korea, and that thereafter, communism itself began its recession in Asia.”12

Each side’s negotiating team consisted of five principal military delegates. Admiral Joy, commander of U.S. Naval Forces Far East, led the UN team, which included Maj. Gen. Paek Sŏn-yŏp, the commanding general of the ROK I Corps, who represented the ROK but only as an observer. On the communist side, the senior delegate was Lt. Gen. Nam Il, the NKPA’s chief of staff and a veteran of the Soviet Army in World War II, where he participated in some of the greatest battles including Stalingrad. The Chinese, however, took control of all major policy decisions at the talks, but only after coordination with Moscow. The initial meeting was held on July 10 at Kaesŏng. The UN team soon realized that it had been a mistake to agree to meet in this ancient capital city. The supposed “neutral zone” was a facade as it was full of Chinese and North Korean soldiers. The situation was particularly galling for Ridgway, because UN forces had held Kaesŏng before the talks and withdrew to make it “neutral.” He also appeared to be unaware of Kaesŏng’s symbolic importance to the North Koreans until after the talks began. Over a thousand years earlier, Kaesŏng had been the capital of the ancient kingdom of Koguryŏ, whose territory encompassed all of North Korea as well as a large part of Northeast China. Koguryŏ was conquered by a southern kingdom, Silla, in the unification wars of the seventh century. Silla’s ancient territory was now part of South Korea. For North Korea, seeing itself as part reincarnation of Koguryŏ and engaged in another war of unification, Kaesŏng symbolized, if not the possibility of a reversal of that ancient defeat, at least the continued preservation of the northern “kingdom.”

The UN delegation arrives at the negotiation site in Kaesŏng, July 10, 1951. (U.S. ARMY MILITARY HISTORY INSTITUTE)

It was soon apparent that the Kaesŏng arrangement was a propaganda stage rather than a sincere venue for talks. The UN delegation was required to arrive bearing a white flag as if in surrender and to be escorted by communist troops, journalists, and photographers. The UN press corps, much less soldiers, were prevented from entering the area. The UN, or more specifically, the Americans, were portrayed as coming to Kaesŏng to plead for peace. The talks got off to a predictably rocky start. “At the first meeting of the delegates,” recalled Admiral Joy, “I seated myself at the conference table and almost sank out of sight. The communists had provided a chair for me which was considerably shorter than a standard chair.” Meanwhile, “across the table, the senior Communist delegate, General Nam Il, protruded a good foot above my cagily diminished stature. This had been accomplished by providing stumpy Nam Il with a chair about four inches higher than usual.” Other indignities followed. During a recess, Joy was threatened by a communist guard “who pointed a burp gun at me and growled menacingly.” Joy’s courier, who had been instructed to carry an interim report to Ridgway, was halted and forcibly turned back. A guard posted “conspicuously besides the access doorway wore a gaudy medal which he proudly related to Col. Andrew J. Kinney was for ‘killing forty Americans.’” Joy had had enough. On July 12, the UN delegation walked out. The talks resumed three days later after the armed communist personnel were withdrawn.13

After much haggling over the physical arrangement of the negotiation room, the discussion finally turned to the agenda. The UN delegation presented three main items: establishment of a truce line, exchange of POWs, and an enforcement mechanism for the armistice. The communists agreed to these but added one more: the withdrawal of all foreign armed forces from Korea. Joy rejected this item as a political matter, which it was, and not appropriate to the armistice talks, which were limited to military matters. A few days later the communist side agreed to drop the withdrawal issue after the UN team stood uncompromisingly firm against its inclusion. The communists then raised the stakes by proposing that the 38th parallel be the line of truce and that a cease-fire be declared during the negotiations. When the talks started, UN forces were in possession of a significant amount of territory in good defensible terrain north of the 38th, especially in the eastern and the central regions. Using the 38th as the truce line would be highly disadvantageous to the UN. Mao confided to Stalin that “it is possible there will be some divergence,” but “our proposal is extremely just and it will be difficult for the enemy to refute.”14 Since the 38th had been recognized as the boundary before the war, the communists advocated that it be simply restored. The UNC rejected the proposal outright, stating that the 38th parallel “has no significance to the existing military situation.”15 A proposed cease-fire was also rejected as it was seen as a ruse to build up and strengthen the communist forces.

The communists were angered by the UN response. General Nam described the UN position as “incredible,” “naïve and illogical,” and “absurd and arrogant.” Nam then proposed the 38th parallel as the truce line with a twelve-mile-wide demilitarized zone, in contrast to the UN’s proposal for a twenty-mile-wide zone. The talks deadlocked. A perturbed Mao wrote to Stalin for advice. A month had passed, and no progress had been made. The truce line was, thus far, the only issue discussed. Mao had come to believe that “from the entire course of the conference and the general situation outside the conference, it is apparent that it is not possible to force the enemy to accept the proposal about the 38th parallel.” He concluded, “We think that it is better to think over the question of cessation of military operations at the present front line than to carry on the struggle for the 38th Parallel and bring the conference to a breakdown.”16 Under pressure from Washington, the UN team made a concession: to accept the communist proposal for a twelve-mile-wide demilitarized zone. The communists stated that they were considering the line of military contact, as proposed by the UN, for the truce line.17

The communists abruptly broke off the talks on August 23, alleging that an American aircraft had bombed a neutral area near Kaesŏng. They also alleged that a few days earlier “enemy troops, dressed in civilian clothes, made a raid on our security forces in the neutral zone in Kaesŏng,” killing a Chinese soldier and wounding another.18 The UN delegation refuted the allegations after its own investigations.19 Yet, given Mao’s earlier message to Stalin that he wanted to avoid a breakdown in the negotiations “at all costs,” it is difficult to understand why such incidents would have been staged. It is likely that the ground raid was the work of South Korean partisans conducted without coordination or permission from the UNC. The ROK Army and partisan operations had been responsible for a number of previous violations in the area, and it is possible that President Rhee, who vociferously opposed the talks, ordered them to disrupt the negotiations. Mao wrote to Stalin in late August that “the enemy, in justifying himself, stated that this was [committed by] partisans from the South Korean partisan detachment active in our region, and therefore he does not take any responsibility for it … The negotiations will not be resumed until we receive a satisfactory answer.”20

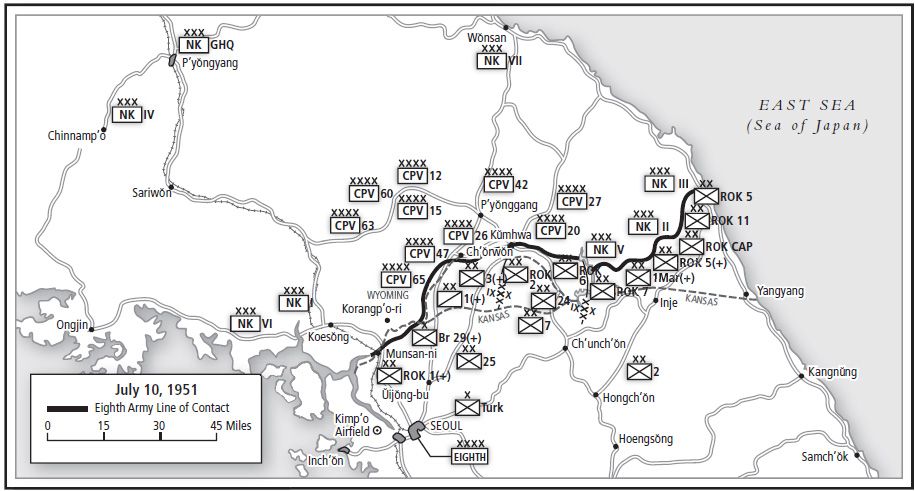

The front line in early July 1951. (ADAPTED FROM WALTER G. HERMES, TRUCE TENT AND FIGHTING FRONT, U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, 1996)

The talks remained suspended for the next two months, during which time the UNC conducted a series of limited-objective attacks that pushed the front line north an average of fifteen miles. In the meantime, Ridgway had been fighting a less visible, but no less hotly contested battle with Rhee. The old patriot was adamantly opposed to a truce of any kind. In mid-July, Rhee pressed Ridgway to continue the war to victory. Van Fleet alerted Ridgway to “rumors to the effect that the ROK Army was prepared in the event of any settlement along the 38th parallel, to continue the fighting regardless of the consequences.” Ridgway then reminded Rhee that “if the UN troops were withdrawn from Korea, the country would be united in slavery.”21 Truman warned Rhee that “it is of the utmost importance that your Government takes no unilateral action which would jeopardize the armistice discussions.”22 Truman implied that should Rhee continue to oppose the talks or threaten unilateral action, the U.S. and other UN forces were prepared to withdraw from Korea. Temporarily chastised, Rhee nevertheless continued to disrupt the armistice talks in other ways, hoping that the UN team’s mounting frustration with the communists would eventually lead to the end of the negotiations and a resumption of an all-out effort to “win” the war.

Meanwhile, other nations, especially the British, were pulling Washington in the opposite direction, urging a more flexible stance to get the talks moving and an armistice signed.23 India proposed that the foreign ministers of the major powers meet to get the talks back on track.24 While the Truman administration had no intention of broadening the number of participants in the negotiations, Washington was also aware that the longer the talks dragged on, the greater the pressure of “world opinion” to resolve matters quickly. To make matters even more complicated, Ridgway insisted that the site of negotiations be moved from Kaesŏng to a neutral zone. The communists refused, accusing the Americans of “creating a pretext for breaking off negotiations.” The impasse finally ended in early October when the Chinese agreed to move the venue to P’anmunjŏm, south of Kaesŏng, in no-man’s land between the two sides. The talks resumed later in October, with the truce-line issue at the top of the agenda. Despite pressure from the allies, Ridgway showed no flexibility in terms that now included the return of Kaesŏng to UN control in exchange for territory on the east coast.25

Facing another deadlock, the communists made a surprising offer. In what many rightly viewed as a breakthrough and a major concession, they offered to accept the battle line, instead of the 38th parallel, as the truce line, provided the UN agreed to its implementation immediately. In effect, they proposed that the fighting stop before other issues are resolved and an armistice is put into effect. The UN team rejected the offer. Suspending all military operations would mean a de facto ceasefire, which would end any leverage the UN might have to influence the communists’ behavior. “The agreement to this proposal,” argued Ridgway, “would provide an insurance policy under which the communists would be insured against the effects of the UNC military operation during the discussions of other items on the agenda.”26 If the proposal was accepted, the communists could indefinitely drag on negotiations on the remaining agenda items without fear of UN military reprisal.

Washington was upset at Ridgway’s rejection. The UN team’s rigid position threatened to drag the war on unnecessarily and was affecting public support for it. An opinion poll in October 1951 revealed that 67 percent agreed with the proposition that the war in Korea was “utterly useless.” Senator Robert Taft (Ohio), a Republican presidential candidate for 1952, attacked the administration: “Stalemated peace is better than a stalemated war … we had better curtail our losses of 2,000 casualties a week in a war that can’t accomplish anything.”27 The British, America’s most important ally, in particular, were concerned by what they perceived as “American intransigence.”

With public and official opinion in the United States and abroad swinging in support of the communist proposal, the State–Defense committee that oversaw the negotiations in Washington informed Ridgway, through the JCS, of the following: “Throughout we have taken as basic principle that the demarcation line should be generally along the battle line. Communists now appear to have accepted this principle. We feel that in general this adequately meets our minimum position re DMZ [demilitarized zone].” Regarding Ridgway’s concern that the communists would drag on the negotiations indefinitely while a de facto ceasefire was in effect, the message proposed provisional acceptance “qualified by a time limitation for completion of all agenda items.”28 This meant that the truce line would become void if an armistice was not completed within the deadline.

But Ridgway was still not amenable. He was convinced that without the leverage of constant UN military pressure, the communists would lose a sense of urgency and incentive to make progress in the talks and would continue to strengthen their forces during the respite. The service chiefs disagreed. They felt that the provisional truce was not a de facto cease-fire and certainly did not affect air and naval actions. The truce-line agreement was finalized on November 27 over Ridgway’s strong objections. It would expire if other issues were not finalized by December 27. After nearly six months of frustrating negotiations, the first significant agreement had finally been reached. The talks now turned to the remaining agenda items: an armistice enforcement mechanism and the exchange of POWs.

Admiral Joy requested an exchange of POW rosters and immediate admission of representatives from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to the communist POW camps. Neither side knew the names or precise number of prisoners held by the other side. Ridgway was initially instructed to seek a POW exchange on a one-for-one basis until all UN prisoners had been returned, and then repatriate the remaining communist prisoners. But there were problems with this scheme. Dean Rusk pointed out that the UNC held about 150,000 prisoners, mostly North Koreans, compared to “less than 10,000 United Nations personnel in enemy hands,” and thus the repatriation of all communist POWs “would virtually restore intact to North Korean forces equivalent to the number it possessed at the time of the aggression.”29 This was a moot point under the Geneva Convention, which required repatriation of all POWs by the detaining powers. Although the United States had yet to ratify the 1949 convention, it felt bound to abide by its provisions. However, there was undoubtedly a desire to find a way to limit or delay the reconstitution of the NKPA. Ambassador Muccio raised a related point to Acheson: the long-standing ROK claim that forty thousand of the POWs were South Koreans who had been forced to serve in the NKPA.30 But how could one distinguish between a genuine and committed North Korean soldier, an anticommunist North Korean conscript, an impressed South Korean civilian, a North Korean who may pretend to be an impressed South Korean, and a pro-North South Korean who had willingly joined the NKPA but claimed otherwise? The situation was further complicated, because at least half of the Chinese prisoners appeared to have been former Nationalist soldiers who were impressed into the CPV.

Brigadier General Robert McClure, the U.S. Army chief of psychological warfare, suggested that prisoners be repatriated voluntarily. Citing moral and humanitarian considerations, McClure was concerned that Koreans and Chinese who had been impressed into the NKPA and the CPV would be “sentenced to slave labor, or executed” upon their return. He pointed out the propaganda value of allowing prisoners to choose where they wanted to be repatriated. A significant number of Chinese prisoners seeking repatriation to Taiwan instead of China “would be a formidable boon to Washington’s Asian policies.”31 Furthermore, “if word of it got around, it might encourage other disaffected Chinese soldiers to surrender.”32

The plan was forwarded to the National Security Council. Acheson vigorously objected to it. While he recognized “the possible psychological warfare advantages of the proposed policy,” it was “difficult to see how such a policy could be carried out without conflict with the provisions of the 1949 Geneva Convention which the United States and the Unified Command has expressed its intention of observing in the Korean conflict.”33 The Geneva article pertaining to the treatment of POWs required that all “prisoners of war shall be released and repatriated without delay after the cessation of hostilities.”34 There the matter would probably have died had it not been for Truman’s strong interest in the issue. Truman opposed an all-for-all exchange since it was “not on an equitable basis.” Nor did he want to send back prisoners who had surrendered or cooperated with the United Nations, “because he believed they [would] be immediately done away with.” Truman’s position was strongly supported by a State Department counselor, Charles Bohlen, who “personally witnessed the anguish of Russian prisoners forcibly returned home from German prison camps at the end of World War II, many of whom committed suicide rather than reencounter Stalinism.”35 Truman’s position, tinged with emotionalism and humanitarianism as well as cold war ideology, violated the Geneva Convention, which had no provisions for either the need for equity in the number of POWs exchanged or exceptions to the all-for-all arrangement. In retrospect, the Geneva code was too black and white, a reaction to the huge numbers of unrepatriated and abused German and Japanese POWs held by the Soviet Union after the end of World War II and the forcible repatriation of Soviet prisoners who did not want to go back and wound up executed. It did not consider the possibility that some POWs did not want or could not be repatriated for legitimate reasons.36

But many had reservations about voluntary repatriation. The JCS pointed out that the enemy POWs had been captured while they fought against UN forces, and thus “we had no obligation to let them express their wishes, much less give the other side any pretext for retaining UN troops.”37 General Bradley favored returning all prisoners, “including, even if necessary, the 44,000 ROK personnel [forcibly impressed into the NKPA].”38 Ridgway was also against voluntary repatriation: “We [the UN team] believe that if we insist on the principle of voluntary repatriation, we may establish a dangerous precedent that may be to our disadvantage in later wars with communist powers,” he argued. “Should they ever hold a preponderance of POWs, and then adhere to their adamant stand against any form of neutral visit to their POW camps, we would have no recourse if they said none of our POWs wanted to be repatriated.”39 In early December it was agreed that, at least initially, the UN maintain its position on one-for-one exchange, which would allow the UNC to retain certain classes of prisoners who did not wish repatriation.

The POW rosters were exchanged in mid-December, and each side had cause to complain. North Korea had boasted of capturing over 65,000 ROK prisoners in the early months of the war, and by the end of 1951 the ROK Army identified over 88,000 missing, and yet the North Korean roster contained the names of a little over 7,000 ROK POWs. Part of the discrepancy could be accounted for by the thousands of former ROK Army soldiers who were classified as North Koreans and were therefore among the NKPA POWs. Still, there were tens of thousands who remained unaccounted for. Furthermore, the 4,400 UN POWs listed by the Communists contrasted sharply with the nearly 12,000 Americans and several thousand other UN soldiers identified as missing.40 Likewise, the communists protested that over 40,000 of their soldiers were missing from the UN list. They claimed 188,000 missing while the UN roster listed only 132,000 (95,000 North Koreans, 21,000 Chinese, and 16,000 South Koreans who joined the NKPA). The UNC claimed that 37,000 were determined to be South Korean civilians impressed into the NKPA and were reclassified as civilian internees and thus not included on the roster. The communists protested “that it was not the place of residence but the army in which a man served that determined whether he should be repatriated or not.”41 While both sides cried foul, the striking disparity in the number of POWs made one thing clear: the communists were unlikely to accept the proposal for an initial one-for-one exchange, followed by repatriation of the remaining prisoners. A decision was therefore made to put the voluntary repatriation principle on the table.

The proposal was introduced in early January 1952, with a predictably explosive reaction from the other side. Maj. Gen. Yi Sang-ch’o, a member of the communist delegation, branded the proposal as “a barbarous formula and a shameful design,” which they “absolutely cannot accept.”42 The communists accused the UNC of forcibly holding prisoners and “bluntly violat[ing] the regulations of the Geneva Joint Pledge on POWs’ Rights.”43 After weeks of acrimonious exchange, Joy gloomily concluded that “the commies will never give up in their determination to bring about the unconditional release and repatriation of all of their POWs.”44 The thirty-day time limit on the truce line expired on December 27. As Ridgway had feared, the communists had rested and strengthened their forces during the month-long respite. It appeared that the continuation of a stalemated war was inevitable.

With another deadlock, voluntary repatriation faced, according to U. Alexis Johnson, a “serious rearguard defection in the Pentagon.”45 Robert Lovett, who had become secretary of defense in September 1951 after Marshall retired, searched for another solution. Admiral William Fechteler, chief of Naval Operations, and General Hoyt Vandenberg, air force chief of staff, were now firmly opposed to voluntary repatriation. Joy also expressed doubts, believing that the communists would never concede on the issue. He raised the ethical issue of a policy that would prolong the suffering of American POWs instead of seeking their immediate release: “Voluntary repatriation placed the welfare of ex-communist soldiers above that of our own United Nations Command personnel in communist prison camps”46 However, with Truman still adamantly in favor with the support of the State Department, Lovett agreed not to oppose the idea when discussing it with the president.47 Prime Minister Churchill, who replaced Attlee in October, also agreed with voluntary repatriation for the same reasons Truman wanted it, and played a key role in building a consensus for the policy in the international community. Other European leaders were concerned about the legality and practical implementation of voluntary repatriation, but key allies from the British Commonwealth, Canada and Australia in particular, were assuaged in their doubts by Churchill’s strong support. Doubters also included British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, who reminded Churchill that humanitarianism worked both ways and that British prisoners should not be forgotten. How could the British government back a policy that would seek to put the welfare of communist prisoners before that of their own citizens languishing in enemy camps? Churchill, however, was undeterred. In time, Eden came around. “I did not know that our legal grounds were so poor,” he wrote at the time, “but this doesn’t make me like the idea of sending these poor devils back to death any worse.”48

The crucial challenge was selling it to the communists. The first task was to find out how many communist POWs would opt for repatriation. U. Alexis Johnson, who was visiting Ridgway in early February, wrote, “Hints dropped by communist correspondents at Panmunjom, and other data led us to believe that, as Ridgway put it, numbers and nationalities of the POWs returned, rather than the principles involved, appears to be the controlling issue.”49 If the number of those wanting repatriation was high enough, the communists might be amenable. Ridgway’s staff estimated that about 16,000 would choose not to be repatriated, leaving about 116,000 who would.50 When the communists were given these figures in early April, they did not balk and instead proposed that the issue be deferred until both sides determined the exact number of prisoners to be exchanged. The UNC had reached a point of no return. By agreeing to carry out the screening process, the UNC was now fully committed to the principle of voluntary repatriation and would henceforth be honor-bound not to return those who had identified themselves as anticommunists.

North Korean prisoners who wanted to remain in the South, June 25, 1952. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

The results of the UN screening were as unexpected as they were astonishing. “Our procedures,” recalled Johnson, “were actually designed to favor repatriation. Within the camps, we publicized a command offer of amnesty to all POWs who chose repatriation, stressing that refusing to go home might open their relatives to reprisals, made clear that those refusing repatriation might have to stay on Kŏje Island [UNC POW camp] long after others had gone home, and promised nothing about what eventually would become of them.” The screening revealed that only 70,000, a little over half, wanted to return home, rather than the estimated 116,000. The communists angrily denounced the result when informed of it in late April. With the number of non-repatriates so large, even Johnson admitted, “The possibility of their ever accepting voluntary repatriation seemed remote.”51 Eager to keep the talks going, the UN team responded that they were prepared to return all 70,000 immediately in exchange for the 12,000 UN POWs in an all-for-all arrangement. As for those who did not want repatriation, it was proposed that they be screened again by a neutral international organization.

The communists refused, recessing the talks indefinitely. “We believed that world opinion needed to follow closely what was going on at the negotiations,” wrote Chai Chengwen, a staff member of the communist delegation. “The people who wanted an early end to the war should know where the obstacles really lay.” On May 9, 1952, the People’s Daily published a prominent editorial where “voluntary repatriation” was interpreted as “forced repatriation” against the communist side. “They said that releasing all the prisoners would mean enhancement of our military manpower,” observed Chai. “Our answer was that the Americans’ argument showed that what they really were concerned with was not prisoners’ rights and happiness, but competition in combat forces and military power.”52 The situation seemed insoluble. Sending back those who did not want to be repatriated would mean certain death or imprisonment. The impasse meant either an indefinite prolongation of the existing stalemate or renewed attempts to end the war quickly through drastic action. “So there we sit,” wrote a sullen Walter Lippmann, “or rather, there sit the unhappy prisoners of war, waiting.”53