The first large group of Western prisoners was captured in early July 1950. Among them were fifty-eight Western missionaries, including Rev. Larry Zellers, a Methodist missionary from Texas who had come to Korea fresh out of college to teach English at the Methodist Mission in Kaesŏng, and Bishop Patrick Byrne, an American who along with his secretary, Father William Booth, had willingly stayed in Korea when the war started. “Byrne’s only concern was with the question of where he could serve the Church best,” recalled Father Philip Crosbie, an Australian who was captured at Ch’unch’ŏn. “Since a Church overrun by communists would have more need of such aid as he could offer, he decided to remain in his headquarters in Seoul.”1 Father Byrne had a remarkable record of missionary work in Japan and Korea. He was the director of the Maryknoll Mission in Kyoto when World War II started in the Pacific, but he was not detained by the Japanese. When the war ended he was transferred to Korea to become the bishop.2

Commissioner Herbert Arthur Lord, a fluent Korean speaker, had come to Korea in 1909 at the age of twenty-one, on the eve of Japan’s annexation of Korea. In 1935, he was sent to British Malaya and then to Singapore, where he was taken prisoner by the Japanese in 1942 and interned until the end of the war. He returned to Korea in 1949, nearly sixty years old, to run the Salvation Army branch there. At the outbreak of the war, he remained in Seoul to continue his work. He, along with the French missionaries Father Paul Villemot, Mother Beatrix Edouard, and Mother Eugenie Demeusy, was taken into custody by the North Koreans in early July. Father Villemot was eighty-two years old and in poor health. Mother Beatrix was a frail woman of seventy-six who had spent most of her life in Korea looking after Korean orphans. Within days of the invasion, these Western missionaries found themselves in a school located on the outskirts of P’yŏngyang that had been transformed into a concentration camp for prisoners.

They were soon joined by over seven hundred American soldiers. Among them was Maj. John Dunn, who had been captured at Ch’ŏnan. At the camp, Dunn met Capt. Ambrose Nugent, who had been taken prisoner near Osan. Nugent had been beaten, starved, threatened, and marched on foot from Seoul. He was forced to take part in the first of many propaganda broadcasts that would later haunt him after the war. In early October, the prisoners were moved north to the city of Manp’o. They were aware that something dramatic had happened. News filtered in that UN forces had landed at Inch’ŏn and were moving north. Elated, they thought they would be freed any day, and excitedly prepared for liberation. “We took it for granted that our captors would keep us in Manp’o until the United Nations Forces could reach us,” recalled Father Crosbie. “It seemed that the only other way they could prevent our early liberation would be to take us across the Yalu to Chinese territory, and we reasoned that the Chinese would not want us on their hands.”3 Much to their surprise and disappointment, however, they were told that they would be going north with the retreating NKPA. The North Koreans, it seems, had use for them.

After P’yŏngyang was captured by UN forces in mid-October, the prisoners were marched to the Yalu River to go by boat to a village more than a hundred miles away. But the boats never arrived. “The organizing abilities of our captors were the subject of much bitter criticism as we plodded back with our loads to our old home,” recalled Father Crosbie.4 In Manp’o they met their new commandant, known simply as “The Tiger.” For the next nine days, the prisoners would endure a bitter ordeal that left few survivors. The Death March, as it later became known, began with a warning from the Tiger. On the evening of October 31, he told the prisoners that they had a long walk ahead of them and that they must proceed in military formation. Commissioner Lord voiced concerns for the entire group. “He pointed out that many of the party would find it impossible to march like soldiers, and at a military pace; that for some the attempt would surely be fatal.” The Tiger roared, “Then let them march till they die! That is a military order.”5 And so, at dusk, the prisoners—diplomats, soldiers, elderly missionaries, women, and seven children, all captured at the start of the war—set out on a march toward Chung’an-ni. No one was prepared or equipped to handle a long march or deal with the approaching winter. Nearly everyone was still wearing the same summer clothes they had worn when captured in July. Major Green, who had been captured with Nugent and Dunn near Osan, recalled that “a lot of the guys didn’t have clothing and a lot of them were barefooted, and a lot of people had dysentery.” “We began in the evening,” recalled Father Booth. “We camped in a cornfield not far outside of Manp’o. It was bitterly cold at the time and we slept, or tried to sleep, on the ground.” The next morning it began to snow. Chilled to the bone, the first of many prisoners began to fall out. Nugent recalled that “the merciless pressure was especially weakening for the many who were suffering from severe dysentery, which seemed to be rife among the GIs.” When the marching finally stopped for the day, the prisoners had to spend another night in the open, huddling against each other for warmth.6

Over the next few days, more prisoners, too weak to go on, were left by the side of the road. When the Tiger saw what was happening, he halted the march. The prisoners had been organized into five groups, with an American officer responsible for each. The Tiger ordered the group leaders to step forward and told the five men they would be executed for disobeying orders. Lord pleaded for their lives, explaining that the guards had given permission to leave behind those who could not keep up and that they would be picked up later by oxcarts. The Tiger scoffed and decided to execute one of the officers and singled out Lt. Cordus Thornton of Longview, Texas. As he stepped forward, Thornton whispered to Lord, “Save me if you can, sir.” In a scene burned into the memory of everyone on the Death March, the Tiger convened an impromptu court-martial, found him guilty, and pronounced death. One witness vividly recalled what happened:

“There, you have your trial,” The Tiger announced. “In Texas, sir, we would call that a lynching,” Lieutenant Thornton responded … The Tiger asked Thornton if he wished to be blindfolded. Hearing an affirmative answer, The Tiger handed a small towel to a guard. Another towel was used to tie the victim’s hands … The Tiger moved smartly to face the victim and ordered him to turn around. Pausing for a moment, The Tiger pushed up the back of Thornton’s fur hat. But like Father Crosbie, I had seen too much already; my eyes snapped shut just before The Tiger fired his pistol into the back of Thornton’s head. When I opened my eyes, I saw that the brave young man lay still without even a tremor. The Tiger knew his business well. Quickly putting away his pistol, The Tiger called for Commissioner Lord to come to his side and translate. “You have just witnessed the execution of a bad man. This move will help us work together better in peace and harmony.” In that brief speech, The Tiger managed to outrage both the living and the dead.7

Thornton’s death had a salutary effect on the prisoners. Perhaps it was the sheer bravery and dignity with which Thornton had faced his death that inspired them. During the long march many showed great acts of kindness. Monsignor Thomas Quinlan and someone else assisted Father Charles Hunt, a large Anglican priest with a foot problem who found it difficult to keep up with the march. “Monsignor and his partner were supporting Father Hunt’s upper body, while the lower lagged behind about three feet”8 Natalya Funderat, “a stout Polish woman who was having great difficulty keeping up, was helped for a time by Commissioner Lord, who tied a rope around her waist and pulled her along like a farmer with an ox.”9 Sagid, a seventeen-year-old Turkish boy, was lugging a large suitcase full of clothes for his youngest brother, Hamid. He was the oldest of six children of the Salahudtin family, who had come to Korea as traders. All of them walked except Hamid, who was just one year old. Father Byrne had come down with a serious cold. At night, the others tried their best to warm him with their bodies and protect him from the winter air. The French consul and his staff carried Mother Beatrix for a time. By the fourth day the old woman simply could not go on. When the Korean guards pushed the old woman to get up, Mother Eugenie pleaded with them. She told them the woman they were beating “was seventy-six years old and had spent nearly fifty of those years in caring for the sick and the poor orphans of their country.” Her appeals were in vain. She was executed for exhaustion.10

After nine days the group arrived at Chung’an-ni, later known as Camp 7, where they were quartered in an old school. By then, winter had arrived and temperatures dropped to below freezing. Surveying the sick and dying prisoners, the Tiger believed that exercise would cure their health problems, and ordered everyone outside the next morning. Lord and Quinlan vainly tried to reason with the Tiger that exercise under such conditions was madness. The Tiger responded by placing his pistol to Lord’s head. Father Villemot was carried out into the freezing cold even though he could barely stand. He weakly went through the motions but died three days later. The Combert brothers, both French priests, who had arrived in Korea at the turn of the century, died two days later. More deaths followed. Father Byrne died on November 25. Father Canavan told the others, “I’ll have my Christmas dinner in heaven” and passed away on December 6. Almost everyone was suffering from dysentery. The room that Major Green occupied was so crowded that when the guards wouldn’t let people out, they ended up defecating on themselves and on the people around them. Beatings were also a regular occurrence. Green recalled that “one of their favorite methods was to have a man kneel and kick him in his chin, and they took some of the guys that they got it in for and would make them kneel down against the building and butt their heads against the building till they gave out, fell over.”11 But more than the starvation diet, the illness, the continual beatings, and the deplorable sanitary conditions, it was the “merciless grinding down of men, the dehumanizing process that went on, the attempt to turn human beings into sheep” that Father Crosbie recalled most vividly.12 Many of the prisoners began to lose the will to live. Camp 7 was the first of many POW camps that sprang up along the Manchurian border during the winter of 1950–51. But unlike other camps, which would be administered by the Chinese or jointly by the North Koreans and the Chinese, Camp 7 was run solely by the North Koreans at least until October 1951. The death rate was appalling. Approximately two-thirds of the 750 men, women, and children who marched in October were dead by the following spring.13 At this rate, no prisoners would soon be left alive at Camp 7.

While Major Dunn, Captain Nugent, Father Booth, and other prisoners were out in the cold cornfields near Manp’o at the end of October, Maj. Harry Fleming, an American regimental advisor in the ROK Sixth Division, reached the Yalu. He was the only American during the war to look across the Yalu into China. Farther south, another advisor was fighting for his life. Major Paul Liles had only recently arrived in Korea and was assigned to advise a sister regiment to Fleming’s in the ROK Sixth Division. Liles reached his regiment while the unit was heavily engaged with the Chinese. “The first battle with the Chinese was already going on when I arrived,” he later recalled. “The battle went on all night … and the next morning it became obvious that we were cut off by a road block in the rear.” The ROK soldiers panicked at being surrounded, and the regiment soon fell apart. Liles was able to evade the Chinese for three days, but then was captured.14

Meanwhile, Fleming was contemplating victory as he stood on the banks of the Yalu. He firmly believed that the war was over. “I listened to the radio from Seoul,” he recalled later. “I heard speeches that were being made as to the tremendous victory by the United Nations in Korea, and our morale was pretty good.” That afternoon, however, Fleming received the disturbing message that “[someone] told me that the Second Regiment [Liles’s], which was my support regiment, had been completely decimated in battle, with great loss, and that my regiment was to return to a place called Unsan which was about 75 miles to our rear, and there, rejoin the Division.” As news of the disaster began to hit him, he realized how vulnerable he and the regiment really were: “We had extended our supplies and communications to the point where we just had no contact with the rear whatsoever except through radio.” For the next four days, the regiment fought their way south. Surrounded and out of supplies, Fleming and his party were overtaken by a Chinese patrol. “My interpreter, a Korean by the name of Quan, hit the ground with me,” Fleming recalled. Fleming had fainted temporarily but had come round just in time to see his assistant, Captain Roesch, struggling with a Chinese soldier. “He [the Chinese soldier] stood over Captain Roesch with this burp gun and opened it up into him, killed him.” Shortly thereafter, Fleming was captured.15

Fleming was taken to a collection point called Valley Camp. Located ten miles south of the Manchurian border, the compound, like so many other camps, was originally constructed by the Japanese as living quarters for Korean miners during the colonial period. Each of the mud-walled houses, with three small rooms and a kitchen, housed roughly sixty prisoners. “This meant that the width that each individual had on the floor was so narrow that everyone on one side of the room had to lie on the same side at the same time. You could not lie on your back and when you moved everyone had to move in unison.” There were about 750 men at Valley Camp. “At this time,” recalled Fleming, “I had marched quite a ways, and I hadn’t much to eat, and what I had had, I couldn’t eat, except on very rare occasions. Water was practically non-existent.” Food consisted of cracked corn twice a day and a few frozen turnips. The weather was bitterly cold. Fleming found Liles in the camp, but he was desperately ill. “At the time,” recalled Fleming, “Major Liles was more dead than alive from ulcers on his legs, and a general debilitated condition.” Both men agreed that while Liles was the senior officer, Fleming was physically better able to take command and organize the prisoners.16

The camp was jointly administered by the Chinese and the North Koreans, and the first thing Fleming did was to meet with them to seek permission to visit the entire camp. He did not get far with the North Korean commander, Maj. Kim Dong-suk. Kim insisted that the UN soldiers were not POWs, but war criminals, and should be treated as such. But the Chinese camp commander, Yuen, who was apparently the senior or at least had greater authority than his North Korean counterpart, was more pliable and agreed that Fleming could visit the various compounds within the camp to determine what was needed to improve living conditions. Fleming was shocked by his tour: “Actually the men were suffering from hunger such as we were at the time, [sic] were having hallucinations about food, and I actually got many requests, believe it or not, for things such as chocolate bars, or candy and other things.”17 Everything was filthy, and the men were covered in lice. All suffered from dysentery and many had pneumonia. There was also a serious discipline problem. The Chinese promoted this by causing dissent between the officers and the enlisted men. “The first statement the Chinese made to us,” recalled Liles, “was that ‘you are no longer members of your armed forces’ and to the enlisted men they told them that they wouldn’t have to follow the order of their officers.”18 In their desperate situation, however, the prisoners welcomed the strong leadership that Fleming provided.

One of the first things that Fleming did was to enforce sanitation. The soldiers were told to relieve themselves in a make-shift latrine instead of anywhere, as they had been doing. Water had to be boiled before drinking it. This was a difficult rule to enforce since boiling water was time-consuming and took more energy than most could muster on their starvation diet. A lice-picking routine was also enforced. Fleming’s measures soon began paying off. Of the approximately 750 prisoners at Valley Camp, only 22, or just 3 percent, died.19 Captain Sidney Esensten testified after the war that “the morale of this camp was pretty good and I think that is why our death rate was so low.”20 But there was a price to be paid. Liles recalled, “Major Kim offered to improve rations only if the officers would sign surrender leaflets. We refused.”21 They did, however, sign a leaflet announcing the entry of the Chinese into the war. Soon there were more demands to endorse a pro-communist propaganda. “Kim repeated his warning that all who refused to cooperate would perish,” Fleming later testified. “The younger, stronger officers believed that U.S. forces would arrive to rescue us in a few weeks, and we should tell Kim to go to hell.” But Liles was not so sure: “I had seen on the roads, on the mountainous terrain, the complete absence of U.S. aircraft after 1 December 1950. I predicted a long hard struggle for UN forces before they could again reach the Yalu. My fellow officers called me a traitor, saying I had lost my faith in my own troops. I was more concerned with keeping myself and my men alive, however, than in preserving my own honor and reputation, priceless though it had been, because I was the senior officer.”22 The price for better treatment was the acceptance of some sort of “accommodation” with the communist authorities.

After a two-month stay at Valley Camp, the prisoners marched six miles to Camp 5 at Pyŏkdong in mid-January 1951. It was much larger than Valley Camp, accommodating approximately three thousand men. In the following months, POWs from other temporary camps were transferred to Camp 5. The majority of them came from a temporary collection site called “Death Valley,” so named because of its high mortality rate. Many of the prisoners there had been captured at Kunu-ri at the end of November, where the Second U.S. Infantry Division was nearly destroyed. “The men were more or less down to an animal stage,” recalled Lieutenant Erwin. “They would sit and watch with a wolfish look and if a man was unable to eat, or anything like that, they would always grab it away from him.”23 Men died rapidly at Camp 5. “The camp held about 3,200 by the end of January 1951,” Liles later said. “At this time, the death rate at Pyŏkdong (Camp 5) was 7 per day average, and the corpses were collected by a Korean bullock cart, reminding me of stories of the Great Plague in London.”24

Unlike Valley Camp, Camp 5 was administered only by the Chinese. The conditions, however, were far worse, and once again Fleming began the task of organizing the men to care for themselves. Many compounds did not establish a common latrine. Starvation was making men unruly, hostile, and then passive. Captain Charles Howard, a survivor of Camp 5, recalled, “You don’t think as clearly as you would under normal conditions. A man’s instinct goes back to self-preservation and I know my own personal thoughts were devoted mostly to food. I didn’t think too much about home or my wife, family, because I was primarily interested in food.”25 Some men eventually had no desire for food or life and simply laid down and died. Despite the dire conditions, Fleming attempted to bring order and discipline to alleviate the situation. He organized details to make clean water available, sleeping arrangements so the men would have equitable sleeping space, and a kitchen to control rations so all would have their fair share.26

In late January, Major Kim, the former commandant of Valley Camp, made an unexpected visit. He told the Chinese commandant that he needed twenty prisoners to take with him to P’yŏngyang for ten days to make radio broadcasts. Although the prisoners had already guessed at Kim’s sinister motivations, he assured them that those selected for the trip would be able to broadcast letters to their families. He also promised that they could broadcast the names of the POWs in Camp 5. This was especially enticing to the prisoners, since the North Koreans had not yet released such a list to the ICRC. Ten officers and ten enlisted men, including Liles and Fleming, were selected. Among the other officers were Lieutenant Erwin and Captain Galing, both of whom had come to Camp 5 from Death Valley, and Capt. Clifford Allen, a black officer who had recently arrived at Camp 5 from Bean Camp, another notorious collection center where an estimated 280 of 900 prisoners had died. As dawn broke on the cold winter day of January 30, 1951, the twenty prisoners from Camp 5 set off by truck for the 110-mile ride to P’yŏngyang. They would not return to Pyŏkdong until nearly a year later.

While prisoners at Camp 5 and Camp 7 were slowly starving to death, another group of captured soldiers were in a comparatively better situation. In December 1950 about 250 prisoners captured at the Changjin Reservoir were brought to Kanggye, where they were housed in what once was a large village. There were no barbed wires or any enclosures around Camp 10, only a Chinese soldier who stood guard at each house. Camp 10 was administered solely by the Chinese. The prisoners were provided sufficient food, clothing, and medical attention to sustain a reasonably comfortable life. Only twelve prisoners at Kanggye died, most from battle wounds, between December 1950 and March 1951, a remarkable figure considering that nearly twice that many prisoners died every day at Death Valley and seven daily at Camp 5 during the same period. The reason for the high survival rate at Camp 10, however, had less to do with Chinese benevolence than with experimentation of new methods of thought and behavior modification. The Chinese wanted to know whether they could turn loyal UN soldiers into loyal communists. These experiments, later popularized in the Western press as “brainwashing,” attempted to control the prisoners’ minds through psychological pressure, social conditioning, and reward. The articles published in the camp newsletter, New Life, starting in January 1951, contained pro-communist and anti-American themes. The experiment seemed to be working. The newsletter featured articles like “Truman a Swindler,” “Truth about the Marshall Plan,” “We Were Paid Killers,” and “Capitalism and Its Aims,” and appeared to have been written by the prisoners voluntarily. With “proper” guidance and training, it seemed that UN soldiers could be transformed into pliant communists. At least, this is what the Chinese believed, and they diligently set about working with the prisoners at Camp 10 to accomplish this task.

Prisoners at Camp 10 were told that they were not prisoners but “students,” that “they were fools for being in Korea, for being duped into it, and had no business there.” The Chinese dangled the idea of early release, “the quicker you learn what we have to teach you, the sooner you will be released and sent back to your lines.”27 The men were organized into ten-man squads, each with a leader who was responsible for overseeing the group’s “education.” Private Theodore Hilburn of the First Marine Division later testified, “[The squad leaders] would give us these papers and books and they would mark off a column for us to read and study and he [Camp Commandant Pan] would have the squad leader read to us and then would have us discuss it. They called it going to school.”28 The prisoners were also required to attend larger meetings run by the Chinese. The first such meeting occurred on December 22 with a Christmas party for the prisoners. They were given hot white rice and pork, an expensive treat given that the Chinese soldiers on the front had far worse rations. “The party was held in a large warehouse,” recalled Marine Sgt. Leonard Maffioli. “They had a banner tacked up on all four walls with ‘Fight For Peace’ and such slogans as that. They had two Christmas trees with little candles burning on them.”29

The Chinese also distributed presents, a few pieces of candy, a handful of peanuts, and a pack of cigarettes. Music was played. Some of the prisoners even danced. After the festivities, the Chinese asked for volunteers to give a speech. Master Sergeant William Olson, a veteran of Omaha Beach in Normandy in 1944 who had served in the army for seventeen years, was the first to stand up. Olson told the assembled POWs that they were lucky to have been captured by the Chinese, who had given them food, warm clothing, and tobacco. Conditions at the camp were far better than what Allied POWs had experienced under the Nazis. He praised China’s lenient policy and thanked his captors. The speech was short, but it elicited considerable reactions among those who heard it. “I was shocked to tell the truth,” recalled Master Sgt. Chester Mathis, “that he would get up and talk like that in that short a period because we hadn’t received any indoctrinations or lectures to speak of, and I was really amazed.”30 Lieutenant Charles Harrison recounted, “There seemed to be a general feeling of anger, confusion and distrust amongst everybody.”31 The following week, parts of Olson’s speech, entitled “If the Millionaires Want War, Let Them Take up the Guns and Do the Fighting Themselves,” was published in New Life:

The Germans were Christians. But they did not allow us to spend our Christmas happily. The Chinese do not observe Christmas, but they have arranged this fine party for us. The Nazis beat their prisoners. They spat on us and forced us to stand for intolerably long hours at a time. Some of us who could not stand this torture would urinate in their trousers. BUT THE CHINESE HAVE GIVEN US WARM CLOTHES, BEDDING AND EVEN HAND TOWELS. THEY HAVE SHARED THEIR FOOD WITH US AND GIVEN US THE BEST THEY HAD. This has taught me a lot of things, I can tell you. When I get home this time, they would not get me in the army again. If the millionaires want war, let them take up guns and do the fighting themselves.32

Many prisoners wrote articles for New Life. The general approach to the indoctrination program was to do just enough to survive. “I think I could best explain this passive attitude in the little bits of advice that we were able to get from Major McLaughlin,” recalled Harrison. “He told us that to save lives he saw nothing wrong with going along with the program to a certain extent.”33 To McLaughlin, the senior officer at Camp 10, the articles appearing in New Life were merely a “parody of Communist ideology.” None of the prisoners were physically threatened. “There were no threats of violence,” recalled Joseph Hammond, “just subtle hints that if we learned and studied their so-called truth, we would be released to go home.”34 On March 1, after four months, Camp 10 was closed, and the remaining prisoners were transferred to other POW camps. The experiment appeared to be a success. Prisoners would cooperate with the right amount of pressure and incentives applied incrementally and persistently. Plans were made to expand the “reeducation” program to other camps.

American POWs at an unidentified camp, undated. (U.S. ARMY MILITARY HISTORY INSTITUTE)

Fleming, Liles, Allen, and the other seventeen prisoners from Camp 5 arrived in P’yŏngyang on February 1. Over the next several months, they were interned in various locations in and around the capital city and then settled at Camp 12. They had to attend “indoctrination” classes for three weeks and, as at Camp 10, conduct daily readings and discussions. But conditions were much worse than those at Camp 10. Fleming recalled, “It was through these conditions of life, these predatory conditions of life I should say, that the communists reduced us to a very, very servile state; where they almost got us to the point that we would do anything they wanted us to do, because we had nothing to fall back on, no strength left, and no source of strength. When a man is sick and starving and freezing, he loses his ability to rationalize.”35

After the indoctrination period the prisoners were asked to make propaganda radio broadcasts. Fleming stated that they were told “that anyone who refused would be marched back to Pyŏkdong [Camp 5], which was a distance of 160 miles. In our weakened condition, it was tantamount to death.” Everyone agreed to make the broadcasts, although only five, including Fleming, were selected to participate. The main theme was that “the United States foreign policy should return to that of the Roosevelt era of ‘good-will all over the world’.” Liles later testified that “the broadcast was cleverly written by Major Fleming and was purposely very vague and nebulous.”36 To the prisoners’ great disappointment, they were unable either to broadcast the names of POWs at Camp 5 as had been promised or to read letters to their families.

The prisoners at Camp 12 were the victims of the most intense indoctrination pressure endured by any POW in North Korea. Between February and December 1951, POWs at Camp 12 made over two hundred propaganda radio broadcasts. Some contained outright lies, such as Fleming’s statement that all POWs had received treatment that “[was] in strict accordance with the principles of humanity and democracy.” Other broadcasts were critical of the United States, accusing it of a “grave error in interfering in Korean internal affairs” and demanding that UN forces “should leave at once.” An appeal “inviting UN troops to surrender and promising kind treatment by the communists” was broadcast in late spring during the Chinese offensive. A broadcast in mid-December addressed an Eighth Army report (Hanley Report) that accused the Chinese of killing 2,513 American POWs and 250 other UN prisoners since November 1950 and the North Koreans of killing at least 25,000 South Korean POWs and 10,000 North Korean “reactionaries.” Outraged by the report, which later proved accurate, the Chinese forced the prisoners at Camp 12 to denounce it. Most, if not all, of the POWs later profoundly regretted what they had done. Major Clifford testified after the war, “I was ashamed of the whole recording. I was very pointedly, very, very pointedly, ashamed of any portion of the recording that referred to the Korean War. So far as my name and identity was concerned, I shouldn’t have even done that.”37

There was a constant fear of being purged. Nothing frightened the men at Camp 12 more than the threat of being sent to a camp known as “The Caves.”38 Lieutenant Bonnie Bowling described the Caves as a place of horror where prisoners were sent to die. “The conditions were such that I don’t know anyone who stayed there more than six months and survived,” recalled Capt. Lawrence Miller.39 Lieutenant Chester Van Orman remembered passing the camp on his way to get rations: “There were many Korean, South Korean, bodies that were frozen and laid up on the ground over the entrance of the caves.”40 Captain Allen remembered the Caves as nothing more than “holes in the ground with mounds of dirt piled on top.” The prisoners there “were skeletons, living skeletons or walking corpses … The Caves was a place where life absolutely could not be maintained.”41 Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockley of the Glosters was one of a handful who survived the Caves. After his capture during the battle at Imjin River, and several failed escape attempts that led to a stay at the notorious interrogation and torture center called Pak’s Palace, where two of his ribs were cracked under torture, the British officer was brought to the Caves. “Except when their two daily meals of boiled maize were handed through the opening,” wrote Farrar-Hockley later, “they [the prisoners] sat in almost total darkness. A subterranean stream ran through the cave to add to their discomfort, and, in these conditions, it was often difficult to distinguish the dead from the dying.”42 The exact number of men who died will never be known.

The beginning of the armistice talks in July 1951 brought significant changes in the treatment of the POWs. There was now concern over the number of POW deaths. The communists realized that if conditions were not changed, few, if any, prisoners would be alive by the time the armistice was signed. “The only time we started getting food,” recalled Lt. Col. John Dunn from Camp 7, “was after we were turned over to the Chinese, and that was after the peace talks had started. Up to that time, we were practically living on nothing.” He added, “When they were winning the war, they were a pack of raving animals. They had no respect for anything and would not hesitate a moment about killing a man … The period up until the time these negotiations started was characterized by mass starvation … After that period, they just started feeding people.”43 By the end of 1951, when POW rosters were exchanged, deaths at the camps had all but ceased. “Life at Camp 5 seemed pretty good,” according to Liles, who had returned after Camp 12 was disbanded in December. “Food was excellent (compared to what we had been eating). POWs got rice, steamed bread, pork and potato soup … POWs had blankets, warm winter clothes, were fat and healthy.”44 Beginning in 1952, the Chinese permitted the prisoners to write two censored letters home every month, their first communication with their families since their capture. Together with the better food, clothing, and medical care, the prisoners entered a new period of relative “normalcy” in which daily existence in the POW camps became tolerable.

As their physical conditions improved, the POWs faced a new challenge: the increasing attempt to attack their minds. The Chinese began to systematically apply lessons from Camp 10 at all camps. They pitted prisoners against each other, creating an insidious division between the so-called progressives (collaborators) and the reactionaries (recalcitrants). These divide-and-conquer tactics worked wonders for the communists, as they preyed on weaker prisoners to perform their propaganda work, which in turn exacerbated the social isolation they felt among their peers. But the most insidious aspect of the divide-and-conquer tactics was that whoever had collaborated with the enemy in the past now found themselves stuck in the role of the so-called progressives. This included the prisoners from Camp 12, all of whom had been captured during the fall and winter of 1950–51 and therefore had experienced firsthand the horrors of the POW camps before the conditions changed for the better. For prisoners captured later on, and especially those captured after the truce talks started, it was easy to overlook the intense physical and mental deprivations of the POWs captured earlier. Moreover, almost every POW had collaborated to some degree to survive, whether it was participating in study group sessions or signing unknown documents, but censoring others as “progressives” helped many of them cleanse their own sense of guilt. Some even found a new status. Major Harold Kaschko later recollected, “In late 1952 the food and camp conditions improved sufficiently that a number of prisoners became self-proclaimed heroes, brightening their own reputation by spattering on others.”45

This photo was taken by Wang Nai-qing, a former Chinese POW guard at Pyŏkdong (Camp 5). Although the picture is undated, it is clear that it was taken in late 1951 or sometime in 1952 when conditions in the camp had markedly improved. The prisoners are well dressed and look generally well fed and healthy. (COURTESY OF WANG NAI-QING)

Soon after Camp 12 prisoners were moved to Camp 5, Fleming, Allen, and other officers were transferred to an officer’s compound, Camp 2, located about ten miles northeast of Pyŏkdong at the village of Pingchŏng-ni. Camp 2 was the only POW camp for officers. The 350 officers there were quartered in a large school that also included a spacious yard. The compound was enclosed by barbed wire and guarded by two hundred Chinese soldiers. After arriving at Camp 2, the officers from Camp 12 immediately sensed that something was wrong. They were greeted by their fellow officers with hostile, stony stares. When one of the newcomers, Maj. David McGhee, went up to a group of Americans, he was asked, sarcastically, “So how’s everything in Traitors’ Row?” It was an indication that the prisoners from Camp 12 would be “treated as pariahs.”46 In the case of McGhee, the question seemed particularly unfair. McGhee was a survivor of both Pak’s Palace and the Caves. He had been sent to the Caves because he had refused to make broadcasts. Yet now he was labeled a collaborator and traitor simply because he had been at Camp 12. “The thing that the men held most against us,” McGhee later testified, “was that we had gone to that group voluntarily, or you might say, with our eyes open. Its announced purpose was propaganda, we had volunteered to go, and it was resented specifically, or most intensely, by the company grade officers [lieutenants and captains].”47

Also taken by Wang Nai-qing, this photo shows UN POWs attending a typical study lecture session at Pyŏkdong (Camp 5). (COURTESY OF WANG NAI-QING)

Major Nugent, whom Liles later described as a “physical and mental wreck” at the time, was similarly disdained. Captain Waldron Berry later testified about Nugent: “I do not recall ever having spoken to him,” he said contemptuously. “His reputation as a collaborator effectively precluded any conversation with him so far as I was concerned.”48 Captain John Bryant recollected that “collectively, [we] had a very low opinion of Nugent and perceived him with the same lack of trust and confidence as was reserved for other members of Traitors’ Row,” adding, “My personal opinion was that Nugent, or other officers who were members of Traitors’ Row … were unfit to be officers of the United States Armed Forces.”49 The prisoners from Traitors’ Row did their best to cope with the ostracization. Liles became withdrawn and depressed. Fleming also withdrew and spent most of his time in the camp “library,” rarely speaking to other prisoners. Captain Allen reacted with anger: “Camp 5 and Camp 2 were living much better than Camp 12 … We [at Camp 12] were the worst off bunch, and still, we were the ones who were called traitors, which is a nasty name. There were a lot of loud mouths there, a lot of self-professed patriots, waving the Flag and calling other people nasty names.”50

By early 1952, deep factional divisions within the camps had emerged. The result was a mini-war of suspicion among the prisoners that played havoc on their morale. “Throughout the thirty-two months that I was prisoner the things that we discussed or things we would plan would invariably get out to our captors,” recalled Lieutenant Chester Van Orman. “It resulted in people getting mighty suspicious of one another.”51 Many thought the Chinese planted rumors or provided special treatment to a particular prisoner to arouse suspicion, to keep the prisoners divided. Only the British officers appeared to be immune from the communists’ tactics. Lieutenant Sheldon Foss thought their “discipline was better than ours and they were, for the most part, a unit. I know some British officers who are still alive and to my knowledge never went along with them [the Chinese]. These included Colonel Carne, commanding officer of the Gloucestershire Regiment; Major Joseph Ryan who was with the Royal Ulster Rifles; and Major Sam Weller of the Gloucestershire Regiment.”52

Fleming, Nugent, and many other POWs emerged from their captivity emotionally shattered and with intense resentment against communism. Commander R. M. Bagwell later noted that “on many occasions in private conversation with Fleming, we discussed the communist menace, and he shared my feelings, he had an extreme dislike bordering on hatred for any part of that system.”53 Similarly, Nugent “was outspoken in his hatred [of the communists],” Maj. Filmore Wilson McAbee later testified. “He appeared to have an intense, almost pathological hatred for them.”54 Despite daily exposure to communist doctrine, very few UN prisoners emerged from their prison camp experience transformed into communists.

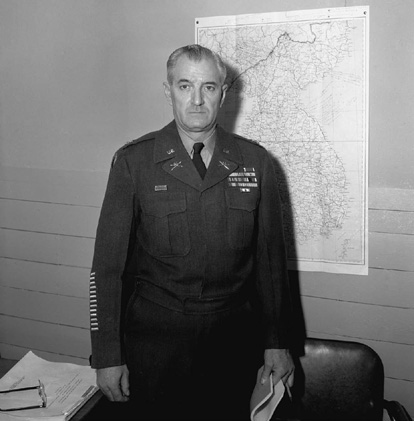

Major Ambrose Nugent, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, January 1955. Nugent was court-martialed in 1955 on charges that he collaborated with the enemy by making propaganda broadcasts and signing leaflets urging American soldiers to surrender. After the six-week trial ended, he was cleared of all charges and promoted to lieutenant colonel. Nugent retired from the Army in 1960 and died in 1988 at the age of seventy-eight. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Return of the Defeated (Toraon p’aeja), a unique and incisive personal account of a South Korean POW’s experience, was published in 2001. Its author, Pak Chin-hŭng, had been a soldier in the ROK Sixth Division in the very same regiment where Maj. Harry Fleming had served as its chief American advisor. It was the only UN unit to reach the Yalu River. Pak was nineteen years old when he voluntarily enlisted in the army. At the time of his enlistment he had been a first-year medical student at the Taegu medical school. Fifty years later, at the age of seventy, Pak published his memoir. It was one of a small handful of memoirs written by former South Korean POWs that began to be published in the wake of democratization in the 1990s.55 That Pak had waited so long to write had been as much due to political necessity as personal choice. South Korea until the early 1990s was authoritarian, virulently anticommunist, and inhospitable to former South Korean soldiers who had ended up as POWs in communist prison camps. They were suspected of being sympathetic to communism or worse: being closet communist spies. South Korea’s democratization allowed Pak to freely revisit his past, but he did not take much satisfaction from it. He is a man consumed by bitterness and regret at having been long rejected by the country he so loyally served.

Pak’s regiment was under a Chinese onslaught in late November 1950. After two days of grueling fighting, he faced the unpleasant realization that the officers in his unit had deserted. Pak was captured by the Chinese at Tŏkch’ŏn. After being interrogated, he was marched north to a former Japanese coal mine in Hwap’ung that was used by the NKPA as a temporary holding camp for prisoners. The Chinese forced Pak to carry wounded Chinese soldiers through the arduous mountain paths, but he did not mind. He was impressed by their commitment not to leave their wounded behind. Certainly, this contrasted sharply with his own experience when his officers simply got up and abandoned him and the hundreds of wounded at Tŏkch’ŏn.

At Hwap’ung, the Chinese handed the South Korean prisoners over to the North Koreans. Living conditions were deplorable, but the North Korean guards were hardly better off. Prisoners were given just 150 poorly cooked kernels of corn per day. They were bitterly cold, sick, and starving. Nevertheless, Pak was able to take comfort in the warm camaraderie among the prisoners. “There was no discrimination based on rank, age or authority or wealth,” he wrote. “We all shared equally.” One day, Pak unexpectedly found a pot of salt hidden in the ceiling. This was literally manna from heaven. All the prisoners had been suffering from salt and vitamin deficiency. He informed the others in his room and carefully divided the salt equally among them. “I could not believe how delicious the salt tasted,” Pak later recalled. “It was unbelievably delicious. Sweet, salty, just beyond words. I put a kernel of corn in my mouth, licked the tip of my finger and carefully picked up one grain of salt and put it in my mouth. We could hardly describe how delicious the corn tasted!”56

In January 1951, life at Hwap’ung came to an abrupt end and the prisoners made an arduous winter march north to Camp 5 in Pyŏkdong, the same camp to which the Americans from Camp 12 would be transferred. Pak recalled “the death march to Pyŏkdong as the most difficult time of my life. None of us had an overcoat and the cold wind swept down from the mountains and up the valley. We constantly fell. We had to shorten our stride to prevent from falling, but that meant jogging rather than walking.” When they arrived, the camp was already full of prisoners. South Korean prisoners were separated from other UN soldiers, but they all lived under the same deplorable conditions. They were given a starvation diet of two meals a day consisting of roughly seventy corn kernels. The death toll of South Korean prisoners was horrendous, twenty to fifty per day according to Pak. But their deaths were not wasted. “When someone died, all his clothes would be taken off and divided among the living. The dead were disposed completely naked,” Pak wrote. Even the lice-infested clothing from typhoid victims was prized among the prisoners. Since typhoid is transmitted by lice, wearing these clothes was a dangerous undertaking. Pak came up with a simple solution. Every night he would take off one pair of clothes to hang outside, and by the morning the lice were frozen to death. “They don’t fall off easily, so I have to beat the clothes with a stick. This is how I killed them. On very cold nights, even the eggs died. It was much more efficient and effective than catching them by hand.”57

In the midst of the misery, the North Korean guards still insisted on calling the prisoners “Liberated Soldiers,” liberated from American imperialism. Like other UN prisoners, South Korean prisoners were forced to undergo “ideological educational studies,” but they were meant to appeal more to the stomach than to the mind. “During these study sessions we expected propagandistic lectures with extravagant claims. But they weren’t … the gist of the sessions was: don’t stay here starving, volunteer for the People’s Army. Fight for the fatherland and eat rice and meat. They didn’t try to agitate or incite us. It wasn’t coercive like asking those to volunteer to step forward. They used persuasion.” In other words, the prisoners could risk dying of disease and starvation in the camps, or they could join the NKPA and risk dying on the battlefield for their nation and their people with glory and honor. In the meantime, they would also be better fed and clothed. Pak was conflicted about what to do. If he stayed in the camp, he thought he would certainly die if conditions did not improve. On the other hand, he thought about the future. If he joined up with the NKPA, he would never be able to see his family again. Moreover, what kind of life could he expect in North Korea? There was certainly no chance of him ever becoming an officer. How would he, a former South Korean soldier, expect to be treated in North Korea? Still, the offer was tempting as he was consumed by thoughts of food. “The only thing I wished for was to eat. I only thought about food. I could not stop thinking about rice no matter how hard I tried. I was unable to feel sadness or any other emotion. I was becoming an animal but so was everyone else.”58

Not surprisingly, many prisoners signed up. “Most argued that it would be better to volunteer and live rather than stay in the prison camps and die of starvation or typhoid,” Pak lamented. Pak did not volunteer. The painful choice was made all the more poignant when Pak learned that an old classmate from medical school in the same camp decided to join. Pak was shocked by the news. His classmate told him, “How can we survive here. Every day 20 to 50 of us die. How can I survive until the end? We don’t know when the war will end, and if we stay we will surely die. I want to join so I can live.”59 Pak tried to persuade his friend that the war would soon be over and reminded him about his family back home. What about his future in North Korea? But his friend’s mind was made up. As a last favor, he asked Pak to visit his family if Pak survived the war. He wanted his mother and father to know what had happened to him. Pak memorized his address.

After I was repatriated and returned home, the very first place I went to was his house. He hadn’t told us, but he was married and had a daughter. When I conveyed the news everyone broke down in tears. I left his house in a hurry … I felt horrible, as if I had committed a sin by surviving and returning home.60

Pak remembered a similarly tragic encounter just before he was repatriated. His train stopped at Sariwŏn on the way to P’anmunjŏm in August 1953. A North Korean private approached him and said, “I can’t return home even though I used to be a prisoner of the People’s Army like you, because I volunteered. Please tell my family that I am alive.”61 Pak couldn’t forget his tear-streaked face.

In the summer of 1951, South Korean prisoners were moved to another camp located near the town of Anbyŏn in the northern part of Kangwŏn province. The camp was an abandoned school, and unlike Camp 5 the floors were covered with wood. “It seemed like paradise compared to the hell of Pyŏkdong camp,” recalled Pak.62 The prisoners were issued unmarked North Korean uniforms and were fed boiled corn instead of the rock-hard uncooked kernels they had eaten before. They were put to work. Owing to the threat of UN air attacks during the day, they worked only at night. They loaded sacks of rice and corn on a rail car, which they then pushed across a wooden bridge. On the other side, other prisoners transferred the cargo onto freight cars. These were then pushed into a tunnel to avoid detection from the air. Before dawn the rails were disassembled for the same reason. At dusk, the rails were reassembled and the cycle was repeated. Through these laborious measures, supplies continued to get through to the front lines.

Given the stable situation and relatively good living conditions, Pak and a group of prisoners, calling themselves the “Resurrection Band” to signal their “rebirth” as free men, began planning an escape. They would live off the land. They had stolen bayonets and grenades and hid them under the roof tiles. A few days before the plan was to be executed, however, “lightning struck” when one of the men betrayed the group.63 The group was apprehended and interrogated, and Pak, as the alleged leader of the plot, was sent off to P’yŏngyang to be questioned further. In retrospect, it may have been a blessing for Pak that the plan had failed. Unlike American, British, and other non-ROK UN POWs whose chances of a successful escape were limited by their conspicuous appearance, Pak probably could have made it to UN lines. He spoke the language, blended into the surroundings, and otherwise could roam the countryside relatively anonymously. Yet, it was precisely this advantage that became a huge liability for South Korean POWs. Once captured, or recaptured, there was nothing he could do to actually prove his national loyalty. Tragically, many ROK POWs who had successfully made their escape to the South were again incarcerated, this time in UN POW camps, as suspected North Korean spies and infiltrators.

Pak told of one such story involving a Mr. Cho. Like Pak, Cho joined the ROK Army at Taegu and fought with the ROK Sixth Division. He was captured by the Chinese and then sent to a North Korean prison camp. To his surprise, the commandant of the camp turned out to be a close high school classmate. This classmate had fled to the North in 1948 following the suppression of the Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn Rebellion. He recognized Cho immediately. Deeply moved to see an old friend, the North Korean officer helped Cho escape. After an arduous trek south, Cho reached UN lines held by Americans. “But the Americans treated him as a North Korean soldier and took him prisoner,” wrote Pak. “He ultimately ended up classified as a North Korean and was sent to Kŏje Island!”64 Cho’s family tried everything they could to get him released, writing petitions to various agencies and producing his South Korean army serial number as evidence of his service in the ROK Army, but to no avail. Cho was identified as a North Korean POW. He was finally able to return home through the anticommunist prisoner release in July 1953 that had been secretly engineered by President Rhee to sabotage the armistice.

And then there were those who were forced to remain in North Korea as virtual slaves. Many of the ROK prisoners were unaware that an armistice had even been signed. “One day I found it rather strange that I could not hear the sound of airplanes overhead,” recalled Cho Ch’ang-ho, who was able to escape and return to South Korea in 1994 after nearly fifty years of detainment in a political camp in Manp’o and forced labor in various mines in North Korea. “Later, I found out the reason the skies had fallen silent: the war was over.”65 In his memoir, Return of a Dead Man (Toraon saja), published in 1995, Cho claimed that thousands of South Korean POWs were as oblivious to the war’s end as he was.66 Kim Kyuhwan, a POW who escaped to the South in 2003, testified that he had been forced to work in a mine for thirty-five years and had no idea when the war ended. “Six hundred and seventy South Korean POWs were confined to hard labor at the Aogi coal mine in 1953,” he wrote. “There are no more than 20 left now. Over the past five decades, many have died in working accidents, and others have died of old age.”67 According to former POWs who escaped, most South Korean prisoners were sent to work in mines in the hinterlands of the northeast along the Chinese border, the most remote part of North Korea. Since 1994, sixty-five former South Korean POWs have escaped to South Korea through China.68

At the end of the war, 11,559 UN POWs were repatriated, including 3,198 Americans and 7,142 ROK soldiers. According to official figures from the South Korean Ministry of National Defense, however, 41,971 South Korean soldiers remained unaccounted for.69 Assuming that the 41,971 had not been killed in action, what had happened to the missing soldiers? An intriguing Soviet embassy report dated December 3, 1953, was recently discovered in the Soviet archives by a Chinese scholar.70 The report stated that 42,262 ROK soldiers “voluntarily” joined the NKPA, while 13,940 were forced to stay in North Korea after the war as laborers, coal miners, and railway workers. According to a former South Korean POW who escaped to the South in 1994, 30,000 to 50,000 ROK POWs were forcibly held by North Korea and unrepatriated. Another source puts that number at 60,000.71 Thus the number of South Korean POWs who were forcibly held back and unrepatriated ranged from 13,940 to 60,000, depending on the source. These figures do not include the South Koreans who “voluntarily” joined the NKPA, which, as the Soviet report pointed out, were in the tens of thousands, even though one can hardly describe the choice made by starved and abused prisoners to survive by joining the NKPA as “voluntary.” Thus, the Soviet figure of 42,262 “voluntary” nonrepatriates seems rather meaningless. Nevertheless, if the figures are correct, the document does provide insight into the enormous number of South Koreans who were not repatriated after the war. If the December 1953 Soviet report is taken at face value, then a minimum of 56,202 South Korean POWS (42,262 + 13,940) were not repatriated, voluntarily or forcibly, and this is a far higher number of unaccounted South Koreans than the official Ministry of National Defense figure of 41,971. The individual and familial tragedies that lie behind these enormous numbers are staggering.

Considering the fate of many thousands of South Korean POWs, Pak was one of the lucky ones. He had survived and was repatriated in August 1953. At the time, however, he did not feel so lucky. He was elated to hear that he was going to Inch’ŏn when he boarded a bus at P’anmunjŏm. But when he was told that he and his fellow prisoners would continue their journey by ship, his joy suddenly turned to fear. The ship took him and others to Yongch’o Island off South Korea’s southern coast. Yongch’o had been a POW camp for North Korean prisoners. Pak’s fear turned into rage: “We couldn’t believe it!! How could we be placed in a camp for North Korean POWs!”72 Yongch’o served as a holding camp for the South Korean authorities to screen repatriated prisoners for their political “purity.” Over the next few months the “released” prisoners found themselves prisoners once again, this time by their own government. They felt lonely, anxious, and betrayed, having been given no information when they might return home. For all Pak knew, he would be waiting out the rest of his life on this small, rocky, isolated island. But the worst was his deep sense of betrayal. He had done nothing wrong. He had served his country loyally. What did all his suffering mean if his country did not even recognize his sacrifice?

Adding insult to injury and fueling the sense of betrayal was Pak’s back pay for the three years he was a prisoner. The amount came to a little more than a few dollars. Furious, Pak “wanted to throw on the ground the pittance I received as compensation for the thirty-three months of suffering.” Not wanting to handle the money himself, he asked a fellow prisoner to buy something with it. “I thought the money was unlucky and didn’t want to put it in my pocket, but when I saw what he came back with from the camp store, I could only sigh. He held one bottle of cheap liquor and a few cans of meat.”73 This was what three years in a North Korean prison camp was worth to his country, he thought. He and his friends drank the cheap wine “made with potato liquor and food coloring” and fell into a deep, troubled sleep. He had blown his three years of back pay in one night of drunken slumber.

Not long thereafter, prisoners began committing suicide. Rather than fling themselves off the cliffs of the island where their bodies would be swept away by the ocean, they chose the most gruesome method possible, hanging themselves in the latrine. “I saw an unbelievably shocking sight. How could this happen, I thought! I reopened my closed eyes and saw my fellow prison-mates hanging on ropes. Not just one or two, but 10 of them! I couldn’t tell who they were. Nobody moved but simply stared at the hanging figures. Another 7–8 prisoners hung themselves the next day and another 4–5 the following day.” The camp commandant prevented the suicides by increasing security and surveillance, but this only heightened the stress on the prisoners as they now had less freedom to move about: “All we did was eat and let time flow by.”74

Confined to barracks on this isolated island in the middle of nowhere, Pak slumped into a deep depression. One day he was informed of the screening process that the detainees would have to go through. The screening would determine whether they were ideologically “fit” to reenter South Korean society. “In the 1950s, everyone thought that if you had been exposed to communism, even for a few days, you could be turned into a communist,” complained Pak. “This is something we all had to go through.”75 The prisoners were uneasy. If the screening process determined that a prisoner was a communist, they would have no future in South Korea. Their fate hinged on the decision of the screener. To his relief, Pak passed the screening. He was determined to be “ideologically sound” and could leave Yongch’o Island and his life as a POW. He was given a two-week leave to visit his family in Taegu, and was to report to the recruiting office at Tongnae, near Pusan, where he would be given his new assignment. Despite his three-year service in the war, he would not be discharged from the army.

At home in Taegu, Pak realized the great gulf that now existed between himself and his former life. Some childhood friends invited him to a coffee shop to talk about old times. When he arrived, he felt out of place. His classmates were dressed in stylish clothes and wore their hair long. They laughed easily and freely. When Pak asked them how they had passed the war years, they told him that they had avoided military service so that they could continue their studies. How was it possible that he was the only one of the group who had volunteered? “I was the only fool here,” he thought to himself. To make matters worse, a policeman approached them and singled Pak out. Someone had reported him as a suspicious character, and the policeman wanted to see his identification papers. He said that he had left them at home. A commotion ensued. Pak was humiliated and indignant: “How dare they who didn’t serve in the army much less seen a battlefield, living safely in the rear, ask me, who had not only fought in the war but had suffered as a POW, for identification papers!” The next evening, still boiling with anger, he thought of his classmates. “I thought of their easy-going laughing faces. Some welcomed me while others secretly jeered. I also thought about the contemptuous looks of the young women at the coffee shop. I thought about the disabled veteran in shabby clothes with a crutch who came into the coffee shop. He didn’t even have a prosthetic leg so one of his pants legs flopped around. He had given one of his legs for his country but became a beggar. Compared to those who avoided military service, he was condemned to live in the shadows of society for the rest of his life. I could only pity him.”76

After his two-week leave, Pak reported for duty to his new unit and was sent to the DMZ. The cold and deprivation reminded him of his days in the prison camps. “I could barely contain my hunger,” he remembered. “I could barely put up with my misery and self-pity. How did I wind up like this, suffering like this in this mountain valley while others were studying.”77 He had given so much for his country, and yet others who had shirked their duty were living comfortably at home. How could this be? Pak was at last discharged from the army in March 1954. He decided that he would try to forget the past. He would resume his medical studies and become a doctor. He would not let the trauma of war and his bitterness ruin his life.

Then, one day in 1995, Pak read about a POW who had escaped from North Korea. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the death of Kim Il Sung in 1994, it appeared that North Korea was on the verge of collapse. Escapees and defectors trickling out of the country began to tell stories of famine and extreme hardship. South Korea, too, was undergoing a period of unprecedented transition. Kim Dae-jung was elected president in 1997, the first opposition leader to be elected in South Korean history. Kim initiated a new policy to engage North Korea (Sunshine Policy), ushering in a period of unprecedented cooperation between the two Koreas. Pak no longer had to suffer the stigma of silence that he felt imposed on him by South Korea’s former military dictatorships. Ironically, though, in the new age of North-South rapprochement, the South Korean government did not want to publicize any harsh criticisms of North Korea for fear that it might wreck the delicate negotiations between the two countries. And so Pak’s story remained “undesirable.”

Pak began writing about his experiences as a South Korean POW for an obscure daily, Yŏngnam Today, in 1999. He felt as if he and other POWs had been doubly forgotten, first by the anticommunist military regimes and then by a democratic South Korean government that was focused on establishing a close relationship with P’yŏngyang. The South Korean government was not interested in pursuing old wounds from the past. Pak’s anger was suddenly rekindled. Why wasn’t the government doing more to locate former South Korean POWs and demand their release from the North Korean regime? Why wasn’t more being done to obtain from the North Korean regime an accurate accounting of the tens of thousands of South Koreans who had disappeared after the war? Why were the South Korean people forgetting the war crimes committed by the North against their own citizens?

Pak read about a former POW, Yang Sun-yŏng, who had escaped to South Korea from the North in 1997. He was owed back pay for the time he was a POW, and the government offered him 2,200,000 won, or about $1,600, for the forty-four years and six months of imprisonment. “I could not suppress my anguish when I heard about this,” wrote Pak. “It amounted to 45,393 won [$33] per year or just 3,782 won [$2.78] per month. That was the pay for an enlisted soldier back then.” Couldn’t the government have found another way to compensate him adequately? “How was it,” he asked, “that the government could give hundreds of millions of won to prevent a bank from going under, but give Yang a mere pittance for his 44 years of hardship as a POW?”78 Pak could not understand. Did his and other former South Korean POWs’ service and suffering for their country mean so little?

Yang was furious too. He refused to accept the compensation money.