When the armistice talks stalled over the POW issue in the fall of 1951, incendiary raids reminiscent of those during World War II were carried out against the North with such effectiveness that Air Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt Vandenberg complained, “We have reached the point where there are not enough targets left in North Korea to keep the air force busy.”1 Charles Joy, chief of the Korean mission of CARE (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere) and witness to World Wars I and II, wrote, “In twelve successive years of relief work in different parts of the world, I have never seen such destitution and such widespread misery as I have seen here.”2 Similar observations were made by the Hungarian chargé d’affaires, Mária Balog, who reported in February 1951,

Korea has become a pile of ruins. There are no houses or buildings left [presumably in P’yŏngyang]. Cities and villages have been blown up, or destroyed by bombings, or burned down. The population lives in dugouts in the ground. The people are literally without clothes or shoes. They cannot even be sent to work, at least until the weather starts warming up. There is no food. Cholera, which the Soviet physicians managed to eradicate in the last five years, may emerge, since it occurred in a district of P’yŏngyang as late as last summer … They are not prepared against these epidemics; there is no medicine and there are not enough medical personnel. There is no soap.3

The rapid descent into the hell of an all-out war left many Americans stunned. Freda Kirchwey, senior editor of The Nation, angrily observed, “Someday soon the American mind, mercurial and impulsive, tough and tender, is going to react against the horrors of mechanized warfare in Korea … liberation through total destruction cannot be the answer to the world’s dilemma.”4 An appalled Harold Ickes of the New Republic wrote, “They [Koreans] had welcomed us to South Korea with shouts of joy. We were deliverers, bringing aid and comfort and unity. Apparently we were bringing other things, wounds and dismemberment and death. Bombs falling from the air or bullets from machine guns being fired into a hurrying or huddled mass, cannot distinguish between the sexes, or between the ages and infants.”5 Upton Sinclair, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author and social activist, worried that devastation by bombing was counterproductive because it fomented a “hatred of Americans in Asia.”6 In Britain, prominent clergymen protested the use of napalm. Emrys Hughes, a renowned Welsh Labour politician, requested permission to exhibit photographs of the P’yŏngyang bombings in the House of Commons, where a similar exhibition of the “Mau Mau atrocities” in Kenya had been allowed in the past, but the request was denied.7

In the end, what determined the debate on the bombing was not the moral argument, but the acceptance by both American and European leaders that the destruction of North Korea was necessary to prevent a greater evil, the possibility of another world war. “Korea is merely one engagement in the global contest,” ran an editorial in the Washington Post. “If we can punish the Chinese severely enough in Korea, a settlement can be achieved … This sober analysis carries little of the glitter or glib promises of the MacArthur formula. But it shows a lot more regard for military risks and realities.”9 With the war at a stalemate by the fall of 1951, Western leaders were of the opinion that bombing campaigns were necessary to punish the communists and force them to the negotiating table. Despite the destruction of North Korean cities, towns, and villages, the success of the bombing was measured by its utility in forcing a settlement and thus preventing a larger war.10

Napalm victims, February 4, 1951. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

P’yŏngyang, 1953. By the end of the war, only three major buildings remained standing. “The gleaming-white building of the bank stands out grotesquely in the center of the city, one of the few buildings that can still be restored. It was used as a hospital by the [UN] interventionists who had evacuated in too great a hurry to blow it up. But beyond it, all the way to the railway station, there is nothing but ruins, a forest of semi-demolished walls and blackened chimneys.”8 (COURTESY OF THE HUNGARIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM).

To a certain extent, the air campaigns were effective in achieving that goal. UN strategic bombing had added to the communist difficulty in sustaining the war. Coping with relentless attacks from the air, Chinese logistical problems multiplied as battle lines moved southward. The UN air interdiction campaign against North Korean rail and road networks was particularly devastating to the Chinese forces.11 General Hong Xuezhi, deputy commander of the CPV force in Korea and also its chief of logistics, recalled that “on 8 April 1951, American napalm bombing runs set 84 rail cars afire, destroying 1,500 tons of grain, 408,000 uniforms, and 190,000 pairs of boots.” As much as 40 percent of all supplies had been destroyed in the bombing raids, and CPV troops were going hungry.12 During the fifth campaign (April 22–June 10), Marshal Nie Rongzhen, who oversaw CPV logistics at the Central Military Commission headquarters in Beijing, described the Chinese troops as “unable to break through enemy lines in the Xianli Sector because they didn’t have food or bullets and they stopped the attack for three days and lost the initiative.”13 With all railways virtually gone, the CPV was forced to resort to trucks, donkeys, and corvée labor to transport supplies from the Yalu to the front, facing great hazards. The countryside had become a moonscape of huge craters filled with water. Trucks operating at night without lights for fear of detection or being attacked by night bombers often drove into the craters, wrecking the vehicle and sometimes killing the driver. General Hong complained, “Even with a hundred men it took forever to fill in a crater.”14

With the front virtually static and under constant air attack, the Chinese were forced to go underground. Tunnels, bunkers, and trenches became the backbone of China’s defensive strategy. Each soldier “had a rifle in one hand and a shovel in the other,” wrote General Hong. The tunnels were constantly expanded under arduous conditions. “The big ‘orchestra’ composed of our soldiers and commanders played a new ‘movement’ in constructing tunnel fortifications,” recalled Yang Dezhi, an army group commander. “This approach meant operating inside the mountains, dealing with rocks, sandy grit, and cave-ins. Lacking technology or advanced tools, we were depending largely on our hands. Pickaxes were worn down so that they ended up looking like rounded iron blocks about the size of a hammer … broken glass and metal plaques were also used at tunnel entrances to reflect sunshine inside during the daytime … They worked so hard that their palms blistered, then became thick and badly calloused.” By August 1952 the Chinese had dug 125 miles of tunnels and 400 miles of trenches. By the end of the war the Chinese had built an astonishing 780 miles of tunnels that formed underground cities. On August 4, 1952, almost two years after China entered the war, Mao optimistically reported, “The problem of food, that is, how to guarantee the provision lines, had been for a long time a real question. We did not know, until last year, that digging up grottos for storing food was the solution. Now we are aware of it. Each of our divisions has enough food for three months. All have their storage and ceremonial halls. They are well off.”15

Despite satisfaction with the underground facilities (“one could find all kinds of facilities, such as dorms, canteens, and latrines … There was also what our soldiers called the underground mansion ‘our club hall’”), life was difficult and stressful.16 Under constant air attack, soldiers spent weeks underground. Coping with the darkness was a challenge. Meager light was provided by oil lamps made from tin cans and shell casings, and keeping the lamps lit used up precious cooking oil. Smoke from the lamps caused headaches and dizziness in the congested and poorly ventilated space. Moreover, the lack of sunlight and poor diet led to nutrient deficiencies with serious effects such as night blindness and diarrhea. Urgent calls were made for shipments of proper food, but “because the shipments were small in quantity, the troops vast in numbers, these shipments were a drop in the bucket and the problem was not solved.” A solution was found through a local Korean folk remedy. Korean peasants showed that night blindness could be cured by drinking bitter “pine needle tea.” The already denuded Korean landscape became ravaged even more by marauding Chinese soldiers searching for the proper nourishment. Tadpoles became a favorite dietary supplement as they were a rich source of vitamins and also helped cure night blindness. General Hong recalled “taking a handful of the little tadpoles from a crater, pop them into a tea pot with some water, best with some sugar but okay without, and gulp them down alive three times a day, and in two days you begin to see results. We got every unit mobilized to play with this clever beverage … once again, the night returned to us.”17

Although the constant bombardment from the air had slowed the communist advance, and thus stalemated the war, it did little to force the communist leadership to a settlement. Despite the destruction, there was little evidence of a collapse of will. As in World War II, intensive strategic bombing could inflict catastrophic damage on a society without defeating it.18 The Chinese and the North Koreans had simply adapted. It soon became clear that the stalemate war could not be won on the battlefield. Rather, it would have to be waged in the court of world opinion. For the communists, this would entail an all-out effort to win condemnation of the United States by discrediting the integrity of the UN war effort in Korea as well as undermining the legitimacy of the principle of nonforcible repatriation.

In early 1951, intelligence reports describing a devastating epidemic sweeping across North Korea reached General MacArthur’s desk. The reports recounted many cases of communist soldiers and civilians dying from a mysterious disease whose symptoms appeared to resemble the bubonic plague. As the Eighth Army advanced northward to recapture Seoul, verification of these reports became a priority. The bubonic plague can sweep though a population like wildfire, blazing a path of death that is difficult to extinguish. A bubonic plague north of Seoul would obviously impact on potential future UNC operations. MacArthur directed Brig. Gen. Crawford Sams, his chief of public health and welfare, to find the truth. It would be a difficult and hazardous task since the allegedly infected area was in enemy territory. Moreover, no one, including Sams, had firsthand experience with the plague. “Not too many of our doctors in America have seen the bubonic plague, and so far as I knew there were none in the Far East at the time,” Sams later wrote. Several reports stated that hospitals in the Wŏnsan area were filled with plague patients. Sams “felt that he should go to Wŏnsan in an attempt to investigate these cases for himself.” Thus began one of the most astonishing episodes of the war.19

The journey posed seemingly insurmountable challenges. Sams decided to enter behind enemy lines by sea. He would travel to near Wŏnsan by ship at night and then get ashore on a row boat. Once he was on land, the journey to find a patient would become more perilous, since he was “an Occidental among Orientals in the dead of winter” and thus without vegetation for cover. He would have to kidnap the patient, take him to the coast, put him on a rubber raft, and then transport him to a waiting ship. “We could then … make our laboratory determination.”20 The operation had to be done quickly and surreptitiously. It seemed like an impossible task, but given the importance of the mission, Sams decided that he had to take the risk. For twelve days in March, Sams tried various ways of getting ashore. Ten teams of Korean agents had been sent in advance to support the operation from ashore, but nothing had been heard from them for several days, and apparently all of them had been captured or killed and the mission compromised. Sams recollected, “Unfortunately, in the torturing which preceded death or execution of these agents, apparently some yielded to such fantastic pressure as the oriental mind can devise in torture, and the communists were aware of the fact that I was trying to get into Korea from that location.” The odds of success appeared nil, and any sane mind would have canceled the operation. But providence struck as the last team of agents, apparently safe, made contact, and Sams decided to proceed.

Sams and Yun, a Korean commando, approached the shore south of Wŏnsan by a little village called Chilso-ni. Yun made contact with the advance team. Over the next few days, Sams hid in a cave while Yun and the other agents scouted nearby villages for victims of the plague. Although unable to capture a patient, Sams was nevertheless able to determine, through the agents who had actually seen many sick people, that there was indeed an epidemic, but it was not the plague. Rather, it appeared to be “a particularly virulent form of smallpox, known as hemorrhagic smallpox.” The “Black Death,” as the epidemic was called, “was as fatal as the bubonic plague except that it was a different disease” and could be more easily controlled through immunization inoculations and medical treatment.21

Sams returned safely with the good news. The communists were furious that Sams had avoided capture. “They executed some twenty-five people in the little village of Chil-So-Ri whom they suspected of having collaborated with us and our agents,” Sams later wrote. But more significantly for the course of the war, Sams’s mission incited a new but still largely uncoordinated charge by the communists that would later erupt into one of the most explosive issues of the Korean War: the accusation that UN forces were engaged in biological warfare. On May 4, 1951, the People’s Daily reported that Sams’s mission was “to spread the plague” and that the ship that had taken him to Wŏnsan was a biological warfare vessel designed to “carry out inhuman bacteriological experiments on Chinese People’s Volunteers.”22

Biological or germ warfare was not a new issue in China. During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) the Japanese established a number of units in occupied China where they worked on developing biological weapons using Chinese prisoners and internees as subjects for gruesome experiments. The most important activity took place at Unit 731 in Harbin commanded by Lt. Gen. Ishii Shirō. The Americans granted Ishii, his subordinates, and members of other Japanese biological warfare units immunity from prosecution for war crimes in exchange for the technical information they had gathered. In the emerging cold war environment, a calculated determination was made that rebuilding Japan, rather than punishing Japanese war criminals, would better serve the long-term security interests of the United States and the free world. In one of the most blatant cases of injustice, Ishii’s men, their past hidden, became ostensibly respectable members of Japanese society as deans of medical schools, senior science professors, university presidents, and key technicians in industries.23 The Soviets put to trial in Khabarovsk the few members of Unit 731 they had captured. The biological warfare methods that the Chinese alleged that the Americans used were precisely the same as those described in evidence and testimonies that came out at the trials.24

After raising the issue of bacteriological warfare in early 1951 following General Sams’s extraordinary mission to North Korea, the communists backpedaled. By mid-May 1951, charges of bacteriological warfare almost disappeared from the communist press. With the prospect of a truce, continuing the accusations seemed unwise. By July 1951, when the armistice talks began, they were dropped completely. It was not until early 1952, after truce talks became deadlocked, that the communists once again raised the charges of bacteriological warfare. In February 1952, North Korean Foreign Minister Pak Hŏn-yŏng accused the United States of repeatedly dropping large numbers of insects carrying cholera and other diseases. The Chinese followed up with charges of their own. In a front-page editorial, the People’s Daily condemned “the appalling crimes of the American aggressors in Korea in using bacteriological warfare.” The accusations gained worldwide publicity with Premier Zhou’s statement on February 24 that called on all nations to condemn the “U.S. Imperialists War Crimes of germ warfare.”25 The communists claimed that one thousand biological warfare sorties were flown by UN aircraft between January and March 1952 in northeast China.

In early April the People’s Daily began publishing eyewitness accounts of germ warfare attacks. An account by a Chinese journalist described how a twin-engine plane had sprayed germ-carrying “poisonous insects” near Xipuli, China, on March 23. Another report relayed how a British reporter witnessed insects being released from an American plane on April 2 in the same area.26 Between mid-March and mid-April, germ warfare allegations with descriptions of strange insects and mysterious airborne voles filled China’s media as the country went on a nationwide insect and rat extermination campaign. The communists also implemented a national inoculation campaign. By October, 420 million people had been inoculated against smallpox. “In our large towns and seaports,” wrote Fan Shih-shan, general secretary of the Chinese Medical Association, “small pox has been completely wiped out … Constant measures taken to destroy rodents and fleas, mass vaccination of local populations, early diagnosis, efficient isolation and energetic treatment have succeeded in controlling the disease.”27

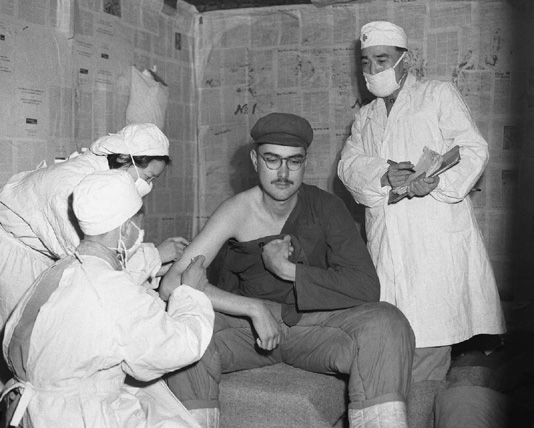

Lieutenant Ralph R. Dixon, prisoner of war, gets inoculated at a POW camp, April 3, 1952. Facing a long and protracted war, Mao inaugurated the Patriotic Hygienic Campaign in 1952 to mobilize thousands of students, housewives, and workers to reduce the incidence of disease and to “crush the enemy’s germ warfare.” In addition, hundreds of thousands of Chinese citizens, including UN POWs, were inoculated against the dreaded disease. Mao also instigated a widespread purge of counterrevolutionaries during this same period. Those who were not immediately executed were systematically “cleansed” of their bourgeois ideology and their “disease-laden” Western inclinations in reeducation camps that began to spring up throughout the country. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

During his captivity in North Korea, Gen. William Dean experienced firsthand the effects of this national campaign when he too was vaccinated. “Everybody, soldiers, civilians, adults and children, received four separate inoculations and revaccination,” recalled Dean. “They were monster shots and all of North Korea had fever and sore arms.”28 American POWs languishing in prison camps along the Yalu were also informed of the germ warfare. William Banghart at Camp 5 recalled that “the bacteriological warfare orientation given to us by the Chinese” consisted of “an elaborate display of pictures, photostatic copies of confessions or statements made by [air force pilots] Lieutenants Quinn and Enoch, and a great quantity of printed matter … One thing I remember clearly is the report I read on the pictorials supplied to the company libraries by the Chinese concerning a Japanese war criminal called Shirō Ishii, who had been released from military prison in Japan and flown to the U.S. where he was supposed to have conferred with President Truman and MacArthur. Every man in the company was given a written test on his feelings on Bacteriological Warfare.”29 One popular slogan was, “One fly, one American soldier; the enemy drops them, we will eliminate them!”30 Political cartoons depicting U.S. imperialism as the Grim Reaper riding the back of a housefly reinforced the notion that the American enemy, and anyone associated with him, was an enemy of China.31 Slogans such as “Resist Germ Warfare and American Imperialism” were calculated to stir hatred for the Americans as disease-laden pests.

The innumerable eyewitness accounts of germ attacks, the lure of war memory, the power of rumor, the fear of epidemic diseases, and the reality of a frustrating war transformed charges of germ warfare into a belief that gripped the Chinese public in terror. Whipped into frenzy, Chinese farmers, housewives, students, and factory workers became citizen-soldiers ready to battle against the unseen and disease-bearing American enemy. This enemy came in many forms. As early as 1949 the CCP leadership had begun launching a campaign to rid the new nation of its counterrevolutionary forces in the guise of the “Suppress Counterrevolutionary Campaign.” The CCP arrested thousands of religious sect leaders, alleged Nationalist spies, and gang leaders, and executed many hundreds. A wide-scale program was launched to crack down on beggars, prostitutes, and criminals. The war in Korea (“Resist America, Aid Korea”) merely intensified the CCP dread of these “internal” enemies. The germ warfare charges arose simultaneously with several new campaigns launched in 1952 that were aimed at the professional classes. The “Three-Anti campaign” and “Five-Anti campaign,” which began at the end of 1951 and in January 1952, respectively, were designed to undermine the authority of China’s capitalists and business managers as well as the rural landlords.32 In February 1952, the CCP also inaugurated the “Patriotic Hygiene Campaign,” which mobilized housewives, students, and workers, equipped with gauze masks, cotton sacks, and gloves, to fight against the American-delivered germs. “Let us get mobilized,” Mao wrote in a memorial to the National Heath Conference in Beijing. “Let us attend to hygiene, reduce the incidence of disease, raise the standards of health, and crush the enemy’s germ warfare.”33

At the same time, the “Thought Reform Campaign” began penetrating institutions of higher learning and professional services. Intellectuals, who had previously thought of themselves as benignly apolitical, or even progressive, were now forced to publicly announce their allegiance. Thought reform classes included not only instructions in proper work ethic, but also the abandonment of “Western influenced elitism.”34 Between February and July 1952, germ warfare was transformed from a regional military-related issue in northeast China into a national mobilization campaign aimed to rid China of all “foreign” influences. Foreign jazz was banned in early 1952. The teaching of English ceased.35 In the hunt for American germs, anyone remotely associated with America—the Nationalists, capitalists, religious leaders, Western-trained intellectuals, businessmen, or managers—was considered a menace to the national body-politic and caught in the same net as insects and rats. In radio broadcasts, mass meetings, and daily newspapers, the Chinese state called on its citizens to expose evildoers, confess crimes, and eliminate poisonous germs from their homes and workplaces.36

The publication of confessions by captured American pilots intensified the popular hysteria. Some wondered why the POWs were even kept alive. In a widely distributed brochure prepared by the China Medical General Association entitled “General Knowledge for Defense against Bacteriological Warfare,” the linkage between the war against germs at home and the war against enemies abroad was made explicit. In both cases, the best defense was vigilance and the eradication of “impure” elements within Chinese society in order to maintain the nation’s health. “It is possible to defend against bacteriological warfare,” the brochure stated. “Under the leadership of Chairman Mao and the Communist Party, we can overcome any kind of weapon, because it is the men holding the weapons, and not the weapons [themselves], that can decide the victory and defeat of the war.”37 By linking American germ attacks with a disease prevention movement aimed to rid China of both its biological and its political impurities, the CCP leadership was able to transform popular dread of American germs into fear of China’s internal enemies that would eventually lead to the persecution of hundreds of thousands of Chinese businessmen, intellectuals, and landowners.38

The hallmark of Mao’s design to purge counterrevolutionaries was his decree on February 21, 1951, which extended the death penalty or life imprisonment to virtually any kind of antigovernment activity. What exactly constituted that activity, however, was never clearly defined. Arrests and purges soon became routine occurrences. The Hong Kong newspaper Wah Kiu Yat Po reported that more than “20,000 persons had been killed in the southeastern districts of Kwangsi [Guangxi], a troublesome southern province,” in March 1951 alone.39 The same newspaper reported the arrests of thousands of people in northeast China. “Mao said that in the struggle against counterrevolution 650,000 persons were executed in the country,” recounted V. V. Kuznetsov, Soviet ambassador to the DPRK, noting as an aside that “some number of innocent people apparently suffered.”40 The goal of the “purification” campaigns was to eliminate entire groups of people from the fabric of Chinese society, and the fear of American bugs provided the perfect pretext to do it.

While Chinese and North Korean officials had little trouble persuading their people that biological warfare was real, persuading the international community was a far more difficult task. The Soviet Union leveled charges of biological warfare through the UN and took the lead in this task. The first official U.S. denial came on March 4, 1952. Secretary of State Dean Acheson angrily stated, “We have heard this nonsense about germ warfare in Korea before [in 1951],” and denied the charges “categorically and unequivocally.” He said he welcomed “an impartial investigation by an international agency such as the Red Cross.”41 General Matthew Ridgway told Congress on May 22 that the allegations “should stand as a monumental warning to the American people and the Free World about the extent to which the communist leaders will go in fabricating, disseminating and persistently pursuing these false charges.”42 A week after calling for an investigation, Acheson sent a request to the ICRC requesting an on-site investigation, under the auspices of the UN, of the allegedly affected areas as soon as possible. Neither China nor North Korea responded to the ICRC’s request for such an inspection. Three additional requests were made, and when they were all ignored, the ICRC considered their request rejected. The only acknowledgment made of the requests was at the UN, where Soviet delegate Yakov Malik formally rejected them on behalf of China and North Korea. Malik charged that a UN-sponsored ICRC investigation would be biased in favor of the United States and the West, and therefore an impartial investigation could not be guaranteed. The UN Political Committee, however, approved the ICRC investigation in early April. It was only on the verge of this expected approval that the Soviet Union offered to withdraw the charge of biological warfare “as proof of its sincere striving for peace.”43

Although the Soviets dropped the charges, the drama was not over. The allegations by the communists had stirred anger among many of America’s leading scientists. Unable to conduct on-site investigations, they examined whatever evidence was available, in this case nine photographs published by the People’s Daily of the alleged insects and voles dropped by the Americans as disease vectors. Scientific experts discredited the photographs as fakes.44 Under pressure of widespread skepticism in the noncommunist press, CCP leaders were unable to let the allegations simply drop because they had staked their regime’s reputation and the basis for national “purification” campaigns on the charges. The ICRC and the UN’s World Health Organization were deemed untrustworthy, but an investigation by neutral outsiders with Chinese oversight would be acceptable. For such an investigation to be legitimate, however, the Chinese government needed a credible group of Western scientists to verify its claims.

To lead the international group, the Chinese invited Joseph Needham, a Cambridge University don from the United Kingdom. Needham was a polymath, one of those exceptionally rare individuals who could rightly be called a Renaissance man. Needham’s scientific credentials were impeccable. He was at the time one of the world’s leading scientists, a pioneering biochemist who had written leading works on biochemistry and embryology. But he also possessed special qualifications in dealing with Chinese matters and especially Mao’s Communist China. He was an avowed leftist and rejoiced in Mao’s victory and the establishment of the PRC, believing that a communist utopia would follow. This view would be tempered later, especially after the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s to early 1970s, but in 1952 no such suspicion entered Needham’s mind. In 1942, the British government posted Needham to wartime China to head a new office in Chongqing, the Sino-British Science Cooperation Office, as a sort of cultural attaché to help spread British goodwill and material assistance among the Chinese academic community. He had never been to China, but had developed a lifelong passion for the country in the late 1930s, even learning the language fluently enough to read classical texts. He stayed for four years and during that time traveled the country widely, amassing a huge amount of material on the history of science and technology in China and establishing a wide network of contacts in the Chinese scientific community. The material he collected formed the basis for a monumental project on the study of scientific and technological developments in China that would prove not only the vastness of China’s achievements but also the indebtedness of the world to China’s genius. It would put to rest the prevailing view that China was backward and had contributed little to the development of mankind. The first volume of his work, Science and Civilization in China, was published in 1954. It is arguably the most important study of China’s scientific history ever undertaken and from a man who was trained neither as a historian nor as a Sinologist.

When Mao invited Needham to investigate the biological warfare allegations, he was in the midst of writing the first volume of his work, and he enthusiastically accepted the chance to return to China and to meet his old acquaintances, including Zhou Enlai.45 Needham was intrigued about the allegations since he had been convinced earlier that the Japanese had used fleas to spread plague in China. He also had to wonder about the connection between the alleged outbreak of “inexplicable” illness in 1951 and the American decision to grant amnesty to Japanese scientists involved in biological warfare in exchange for their experimental data. Needham looked forward to employing his scientific and language skills in the service of the struggling new regime.

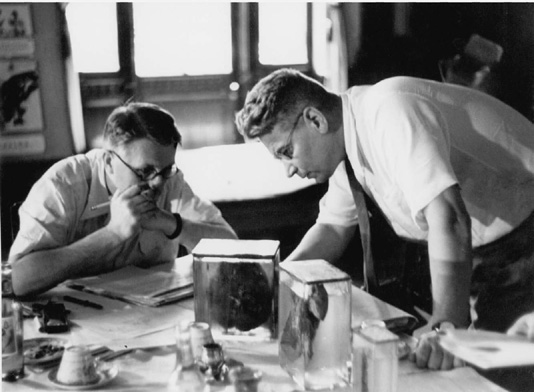

Joseph Needham (seated) and N. N. Zhukov-Verezhnikov examining specimens, 1952. (NEEDHAM RESEARCH INSTITUTE)

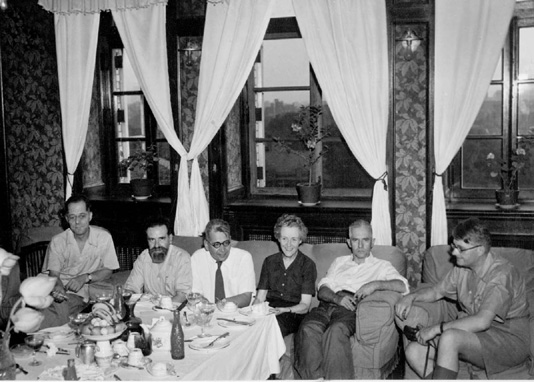

Another key expert invited by the Chinese was N. N. Zhukov-Verezhnikov, a bacteriologist and vice president of the Soviet Academy of Medicine who was also intimately familiar with Ishii’s Unit 731 program. Zhukov-Verezhnikov had served as a medical expert in the Khabarovsk trials of members of Unit 731. Needham and Zhukov-Verezhnikov, along with four other left-leaning Western scientists from Italy, France, Brazil, and Sweden, constituted the International Scientific Commission, formed by the Soviet-bloc World Peace Organization in the spring of 1952, to investigate allegations of germ warfare. The team arrived in June and worked tirelessly over the summer. Their report presenting the findings of Chinese scientists, with commentaries and final conclusions by the commission, was issued on September 15, 1952.

It confirmed everything China had claimed: “These [biological weapons] have been employed by units of the U.S.A. Armed Forces, using a great variety of different methods for the purpose, some of which seem to be developments of those applied by the Japanese army during the Second World War.”46 Curiously, although commission members had significant scientific credentials and were responsible for writing, organizing, translating, and editing the final report, they themselves conducted no direct scientific investigations. Instead they heard testimonies and viewed a vast array of evidence presented to them by Chinese scientists, including an amazing variety of supposed vectors—voles, spiders, nonbiting flies, and other insects.47

Members of the International Scientific Commission (left to right): Olivo Oliviero (Italy), Jean Malterre (France), N. N. Zhukov-Verezhnikov (USSR), Andrea Andreen (Sweden), Samuel Pessoa (Brazil), and Joseph Needham (UK). (NEEDHAM RESEARCH INSTITUTE)

Needham appeared to put particular stake in the reputation of the dozens of Chinese scientists who had participated in the investigations and submitted the evidence, writing later that “they were first rate bacteriologists … and of whom I know well personally and can vouch for.”48 At the same time, he appeared blissfully unaware that the germ warfare investigations were taking place in the midst of a tense climate of political repression, “Thought Reform,” reeducation, and the execution of hundreds of thousands of counterrevolutionaries.49 Neither Needham nor the other Western scientists considered how politics might have compromised scientific truth. Nor did they seem aware that Chinese bacteriologists and entomologists were under intense pressure to cook the evidence and back the government’s claims of American germ warfare. Needham simply could not believe that profound political changes might have influenced the conclusions of the scientists with whom he had become and remained close. He told Dr. Alfred Fisk, an American scientist and colleague, “If anyone insists on maintaining that a large number of scientists or scholars who were excellent men before automatically becoming scoundrels on the same day that a government such as that of Mr. Mao Tse-tung [Mao Zedong] comes into power (a government which, by the way, I am convinced has the support of the overwhelming majority of the people), I do not argue with him.”50

Plague lab, 1952. After spending the summer of 1952 investigating claims of bacteriological warfare presented by Chinese scientists, the International Scientific Commission published a 665-page report on September 15. Archibald Vivian Hill, the 1922 Nobel laureate in physiology and medicine, summed up the Western reaction to the report by proclaiming it to be “a prostitution of science for the purposes of propaganda.” As for Needham, he was proclaimed a persona non grata by the British academic establishment. Needham was also blacklisted by the U.S. State Department and banned from travel to the U.S. until the mid-1970s. (NEEDHAM RESEARCH INSTITUTE)

Joseph Needham examining an alleged biological warfare canister dropped from American bombers. (NEEDHAM RESEARCH INSTITUTE)

In his field notes, however, Needham hinted that many of these exhibitions might have been staged for his benefit. He was uncertain of what he might find when he visited Gannan county, the site of the first reports of purported droppings of germs. After he was invited to observe a technician in full protective gear examining microscopic slides that had been set up in a mobile bacteriological laboratory, he later wrote to his wife, “I have the feeling that this may have been a mise-en-scene for one person.”51 Nevertheless, he gave the Chinese the benefit of the doubt.52 At a press conference following his return home, Needham was asked “what proof he had that samples of plague bacillus actually came from an unusual swarm of voles as the Chinese had claimed.” “None,” he answered. “We accepted the word of the Chinese scientists. It is possible to maintain that the whole thing was a kind of patriotic conspiracy. I prefer to believe the Chinese were not acting parts.”53

Curiously, there were no epidemics in China or North Korea in 1952. The head of the UN World Health Organization, Dr. Brock Chisholm, noted that “North Korean and Chinese reports of epidemics in enemy territory … did not indicate the use of germ warfare because bacteriological weapons would bring far heavier casualties than indicated by the accounts of epidemics.” He concluded that if germ warfare had been waged, “millions of people would die suddenly” and there would be “no mystery as to whether bacteriological weapons had been used.”54 Alternatively, one could also conclude that the hygienic measures put in place were done quickly and widely enough to have prevented epidemics from biological weapons. However, the Western public dismissed the whole episode as a hoax, yet another example of the dangers of communism and how a communist regime promoted lies over truths by subordinating science to politics. It was not simply the cynicism of the untruths that was unsettling, but the darker power of what those untruths revealed about the enemy. “The alarming thing,” the New York Times wrote, “is the demonstration that the power we are fighting is not simply a great, militant and aggressive empire on the make, it is the power of evil. It could be said of the ruling mind in Russia that it has lost the sense of truth. To this mind anything it desires is good, and any lie is truth that serves its end.”55

Members of the International Scientific Commission with Korean and Chinese officials. Needham, with glasses, is seventh from the left. Kim Il Sung is seventh from the right, summer 1952. (NEEDHAM RESEARCH INSTITUTE)

In January 1998 the Japanese newspaper Sankei shinbun uncovered twelve Soviet-era documents. They provided the first evidence that the biological warfare allegations had been fabricated. The documents describe how the North Koreans and the Chinese, with Soviet help, created false evidence.56 One document described how the hoax was carried out. General Razuvaev, the Soviet ambassador to the DPRK, reported, “With the cooperation of Soviet advisers a plan was worked out for action by the Ministry of Health … False plague regions were created, burials of bodies of those who died and their disclosure were organized, measures were taken to receive the plague and cholera bacillus. The adviser of MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs] DPRK proposed to infect with the cholera and plague bacilli persons sentenced to execution, in order to prepare the corresponding [pharmaceutical] preparations after their death.”57

What was the reason for the elaborate hoax? Chinese commanders in the field made the initial charges. Mao ordered scientific investigations to confirm the reports before making them public, but the North Koreans prematurely made their charges before the tests were completed. Mao realized that the charges were false, but he decided to take advantage of the opportunity to discredit and embarrass the United States, to maintain China’s revolutionary momentum while purging its internal enemies.58 This happened while the armistice talks were deadlocked over the issue of voluntary repatriation of POWs, and thus allegations of germ warfare could also be exploited for their propaganda value to gain an edge at the talks. Domestically, it came at an opportune moment for Mao. Fear of political impurity and invisible enemies could help mobilize the nation under Mao’s leadership to be prepared for a protracted war. Mao exhorted the people to report pro-American attitudes in the intellectual and business communities. The germ warfare campaign would make the link between American biological warfare and spiritual contamination of the Chinese body-politic direct and tangible. Internationally, the charges would expose the hypocrisy of the UN policy of voluntary repatriation. While such heinous war crimes are being committed, the insistence that POWs freely choose where they wanted to be repatriated after the war would appear calculated and shallow.

The Soviet Union went along with the hoax until the spring of 1953, when the Soviet delegation at the UN was ordered to “no longer show interest in discussing this question.” Even more strikingly, Moscow told Beijing and P’yŏngyang that the Soviet government was now aware that the allegations claiming that the United Sates had used biological weapons were false. A May 1953 resolution of the presidium of the USSR Council of Ministers (which ran the Soviet Communist Party immediately after Stalin’s death in March 1953) noted that “the Soviet Government and the Central Committee of the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] were misled” and concluded that “the accusations against the Americans were fictitious.” In order to remedy the situation, the resolution recommended that “publication in the press of materials accusing the Americans of using bacteriological weapons in Korea and China” cease and that “the question of bacteriological warfare in China (Korea) be removed from discussion in international organizations and organs of the UN.”59 Apparently, the Soviets had resolved to distance themselves from the hoax because it “damaged Soviet prestige.”60

Regardless of the decisions made by the Soviet Union’s new leadership to abruptly end the propaganda campaign, the allegations had already begun to die down by the summer of 1952. This is because another scandal, tragically of Washington’s own making, did far more damage to America’s image abroad and UN credibility on the POW repatriation issue than communist allegations of bacteriological weapons ever did.

On May 7, 1952, the new UN commander in chief, Gen. Mark Clark, landed at Haneda Airport in Tokyo. General Ridgway was glad to see him. After a year as commander of both the UNC and the Far East Command, Ridgway was relieved to be leaving. “The negotiations with the communists were my major concern throughout most of my remaining tenure in the Far East Command,” Ridgway later wrote. “They were tedious, exasperating, dreary, repetitious and frustrating.”61 Ridgway was going to Paris to be the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), replacing General Dwight Eisenhower, who had decided to try for the Republican nomination in the 1952 presidential election.

Clark had become well known as commander of the Fifth Army in the Italian Campaign during World War II. He had also gained a reputation for being vainglorious. A former superior, Gen. Jacob Devers, described Clark as a “cold, distinguished, conceited, selfish, clever, intellectual, resourceful officer.”62 Clark would have to rely on all of those traits in dealing with the communists at P’anmunjŏm. He had no illusions about the difficulty he faced: “I had been in on much of the Korean planning in Washington and knew that this would be the toughest job of my career.”63 What Clark did not know was that on the very day of his arrival, he would be confronted with one of the biggest crises of the Korean War. On Kŏje Island (Kŏje-do), some thirty miles off the southeast coast of Korea and the site of the main UNC POW camp, Brig. Gen. Francis Dodd, the camp commandant, was taken hostage by North Korean prisoners. They threatened to kill him if their demands were not met.

By December 1951, there had been indications of serious problems in the camp. The first problem was overcrowding. Between September and November, over 130,000 prisoners had been taken, owing to the success of the Inch’ŏn operation. The UNC had not anticipated nor was it prepared to hold such a large number of prisoners. In January 1951, with the number of POWs reaching 140,000, the prisoners were consolidated into one complex of compounds on Kŏje-do to ease the task of holding them and to reduce the number of guards needed. The camp was originally designed to hold 5,000.64 The prisoners were literally packed in with minimal fencing, which permitted them to communicate freely among themselves as well as with local villagers. Through sympathetic villagers and refugees, the Chinese and North Korean authorities were able to pass messages back and forth to the POWs. As a result, the communist prisoners received instructions from and coordinated with P’yŏngyang and Beijing to instigate mass demonstrations, riots, and other disturbances. The inadequate guard force was another major problem. There were simply not enough guards nor were they of a quality “to insure the alertness needed to detect prisoners’ plots or to identify and isolate the ringleaders.”65 As a virtual civil war raged between the prisoners, with former Chinese Nationalist and anticommunist Koreans (many of whom had been forcibly enlisted in the NKPA) clashing with their pro-communist opponents, beatings, mock trials, and murders became a daily occurrence. The UN guards, especially the Americans charged with administering the camp, were intimidated or indifferent and did not take actions to prevent the incidents.

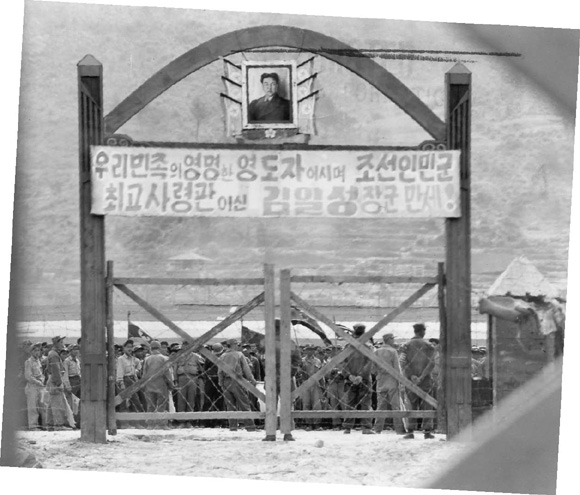

Pro–North Korean compound, May 31, 1952. The banner says, “Long live General Kim Il Sung, the acclaimed leader of our people and the supreme commander of the Korean People’s Army.” (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

In mid-February, a large riot broke out when thousands of staunch North Korean communists refused to allow UN personnel to enter their compound to conduct preliminary prisoner screening. “There were approximately 3,000 civilian Korean internees in Compound no. 62,” wrote Sir Esler Dening, the first British ambassador to Japan after World War II, who was then serving as political advisor to the UNC. “Amongst them were a fairly high proportion of fanatical communists, and the Americans had reasons to believe that these latter were using strong arm tactics to coerce ‘deviationists’ (e.g. anti-communists) amongst the internees into line.” The result was a clash between UN guards and the prisoners that resulted in the death of dozens of prisoners. The incident was the first real indication that something was terribly wrong at Kŏje-do. “Unfortunately, the episode is a very disagreeable one and I fear, brings the United Nations Command nothing but discredit,” concluded Dening.66 R. J. Stratton, chief of the China and Korea Department in the British Foreign Office, was sufficiently alarmed to ask Sir Oliver Franks, the British ambassador to the United States, to raise the issue with the U.S. secretary of state: “If you see no objection, it might be well to draw Mr. Acheson’s attention informally to the possibility of repercussions in the House of Commons, which, as he knows, has a long tradition of humanitarian interest in cases of alleged brutality.”67 The implied “repercussion” pertained to continued British participation in the war.

Camp conditions deteriorated rapidly. P. W. Manhard from the American embassy reported that leaders in the pro-Nationalist Chinese compounds “exercise[d] discriminatory control over food, clothing, fuel, and access to medical treatment,” and pro-Nationalist prisoners controlled former CPV soldiers by means of “beatings, torture, and threats of punishment.” He feared that “mounting resentment among the Chinese POWs [against the pro-Nationalist leaders] constituted an increased threat to the security within the UN POW camp.”68 A detailed public report by UNCURK after the commission’s visit in mid-March described a situation that was clearly out of control. G. E. Van Ittersum, the Dutch representative, wrote that “no American ever enters the compounds … In many compounds there is no sewage. Dead and seriously wounded people are hardly ever extricated.”69 Pro-communist compounds were strewn “with banners and placards with such slogans as ‘Down with American Imperialism.’” General Dodd told the commission that “he did not have enough guards to have these signs removed.” In another pro-communist compound the commission “found about 5,000 communist prisoners formed round a square beating drums and shouting communist songs.” Dodd, “fearing a hostile incident,” requested that commission members quickly withdraw. The commission was barred from entering a third pro-communist compound. The prisoners, he said, “had not allowed any American to enter the camp on the two previous days.” Moreover, during the commission’s visit, “this compound was being bombarded with stones thrown across the road from a non-communist compound.” Unmistakenly shocked, UNCURK concluded, “The visit to Koje-do made clear to the commission members the possibility of further political disturbances.” As for Dodd, “he is living on the edge of a volcano and on any day there might be fresh outbreaks of violence and more deaths.”70

On the evening of May 6, members of Compound 76 asked for a meeting with Dodd to discuss their complaint over beatings by Korean guards and poor living conditions. Compound 76 contained some 6,400 North Korean prisoners who were categorized as “zealous communists” and had violently refused to be screened by UN personnel in April. In exchange for a meeting they agreed to be rostered and fingerprinted. UN personnel had not been able to enter the camp for many weeks, and Dodd was directed to complete a roster of the remaining POWs. Dodd agreed and arrived on the afternoon of May 7 with five guards. He spoke to the prisoners through the fence. Shortly after the meeting began, a work detail of forty prisoners was permitted to pass through the gate under the supervision of two guards. The gate was opened, allowing some of the prisoners talking with Dodd from the inside to step outside. The last few men of the detail suddenly rushed Dodd as they were about to pass the gate and dragged him inside. Bewildered, some of the American guards swung their weapons to their shoulders, but Dodd shouted, “I’ll court-martial the first man who shoots.” The prisoners closed the gates and then raised a sign painted on ponchos, about twenty-five feet in length, which read, in stilted English:

WE CAPTURE DODD AS LONG AS OUR DEMAND WILL BE SOLVED,

HIS SAFETY IS SECURED. IF THERE HAPPEN BRUTAL ACT

SUCH AS SHOOTING, HIS LIFE IS DANGER71

News of Dodd’s kidnapping quickly reached Ridgway. Ridgway informed the Joint Chiefs that the prisoners were capable of a mass breakout, which might result in the capture of the island itself. An American infantry battalion and a company of tanks were immediately dispatched to the island. General Van Fleet appointed Brig. Gen. Charles Colson to take charge of the camp and to negotiate Dodd’s release.

Soon after his capture, Dodd sent a message that he was unharmed but that he would be killed if force was used to try to rescue him. He passed on the prisoners’ demand that two delegates from each of the other compounds be brought to Compound 76, “where a conference would be held to discuss grievances and settle the terms on which he would be released.” The next morning, May 8, Dodd was confronted by representatives from all compounds, Chinese and North Koreans. One by one they spoke, “each having prepared a good deal of evidence” for their accusations of violence and abuse allegedly suffered. It was an extraordinary account of “concentrated and unvarnished tale of murder, torture, and thuggery, rape (for there were delegates from the women’s compound) and of the unrelieved brutality of the men under his [Dodd’s] command.”72 One described how some prisoners had been beaten by other prisoners because they wanted to return to North Korea. Others displayed evidence of torture, claiming that the scars on their bodies had been inflicted by the South Korean guards. “The warehouse bookkeepers explained how the camp supplies were sold by ROK soldiers to the black market. Two female prisoners told their stories about frequent rapes and gang rapes by both guards and prisoners.” The prisoners drew up a list of nineteen counts of death and injury caused by the South Korean guards. One Chinese prisoner recalled that “[Dodd] became nervous and sometimes seemed touched by the stories. He just said: ‘I can’t believe it. I can’t believe it.’”73 On May 10, three days after Dodd’s capture, Colson received a statement written in Korean, with a poor but comprehensible English translation, that the prisoners said he must sign to secure Dodd’s release.

1. Immediate ceasing the barbarous behavior, insults, torture, forcible protest with blood writing, threatening, confinement, mass murdering, gun and machine gun shooting, using poison gas, germ weapons, experiment object of A-bomb, by your command. You should guarantee PW’s human rights and individual life with the base on the International Law.

2. Immediate stopping the so-called illegal and unreasonable volunteer repatriation of NKPA and CPVA [Chinese People’s Volunteer Army] PW’s.

3. Immediate ceasing the forcible investigation (Screening) which thousands of PW’s of NKPA and CPVA be rearmed and falled in slavery, permanently and illegally.

4. Immediate recognition of the PW Representative Group (Commission) consisted of NKPA and CPVA PW’s and close cooperation to it by your command. This Representative Group will turn in Brig. Gen Dodd, USA, on your hand after we receive the satisfactory declaration to resolve the above items by your command. We will wait for your warm and sincere answer.74

Colson was appalled. He could not sign such a document. He responded with a revised version. Dodd offered to modify Colson’s draft so that it was acceptable to both sides. Over the next few hours, Dodd, Colson, and Senior Col. Lee Hak-ku, the POW spokesman, engaged in furious back-and-forth exchanges until a final statement was agreed upon.75 That evening, Colson signed the document and Dodd was released.

It was now up to General Clark to clean up the Kŏje-do mess and make sure that it never happened again. “As Ridgway waved good-bye,” remembered Clark, “I visualized him throwing me a blazing forward pass.” Clark was unsure whether he was ready to catch the ball. Earlier that morning, Clark had written a public statement denouncing the text of the POW demands and of Colson’s agreement. Clark was upset not only that Dodd and Colson had accommodated the prisoners’ demands but also that Colson signed a letter containing incriminating language that could be used against the UN negotiators in P’anmunjŏm:

I do admit that there have been instances of bloodshed where many PW have been killed and wounded by UN Forces. I can assure that in the future that PW can expect humane treatment in this camp according to the principles of International Law. I will do all within my power to eliminate further violence and bloodshed. If such incidents happen in the future, I will be responsible.76

Clark stated that “the allegations set forth in the first paragraph are wholly without foundation,” and that “any violence that has occurred at Kŏje-do has been the result of the deliberate machinations of unprincipled communist leaders whose avowed intent has been to disrupt the orderly operation of the camp and to embarrass the UNC in every way possible.”77 Dodd also released a statement including an account of his capture. He ended it with a justification of sorts: “The demands made by the PWs are inconsequential and the concessions granted by the camp authorities were of minor importance.”78 Clark could not have disagreed more. Colson’s statement and the entire Dodd affair had greatly damaged the UN position. Ridgway agreed: “The United Nations Command was asked to plead guilty to every wild and utterly baseless charge the Red radio had ever laid against us.”79 By admitting that there had been “instances of bloodshed” and that “prisoners of war had been killed or wounded by UN Forces,” Colson had undermined the moral foundation of the UN, and in particular, the principle of voluntary repatriation, which was based on the assumption of fair and equal treatment. Dodd and Colson were punished by being demoted to colonel.80

Clearly changes had to be made at Kŏje-do. Clark sent Brig. Gen. Hayden Boatner, the “tough, stocky and cocky” assistant commander of the Second Infantry Division, to replace Colson. The compounds were broken up, and some prisoners and all civilian internees were moved to other camps. Routine inspections were enforced, and anti-UN or pro-communist banners and signs were forbidden. But the UNC had suffered a severe blow to its credibility. “At the time of the Secretary of State’s statement in the House on the repatriation question on May 7, we had no reason to doubt the validity of the screening process,” wrote Charles Johnston from the China and Korea Department of the British Foreign Office. “The revelations which we now have of the conditions in the camps must give us serious misgivings on the fairness and accuracy of the census.” He concluded, “We still stand firmly on the principle of voluntary repatriation; but we must be sure that the factual foundation on which that principle rests is sound.”81

Acheson told Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden in late May that “the incident on Kŏje Island had greatly weakened the moral position of the United Nations Command,” and that it was “urgently necessary to restore this.”82 Johnston lamented that Britain’s image had been tarnished by the whole affair. He was angry that the British had been kept out of the loop on the Kŏje-do incident. The Foreign Office, however, had been well aware of the troubling conditions on Kŏje-do for quite some time. In December 1951 it had raised concerns about the camp but had been rebuffed. “Is U.S. State Department now in a position to supply the authoritative statement on recent events on Kŏje requested in our telegram No. 2039 of 16 May?” Johnston demanded. “It would be regrettable and embarrassing if the results of the United Nations Command’s enquiry into these recent disturbances on Kŏje were withheld from us, as were those on the 18 February and the 13 March riots.”83 From then on the Foreign Office insisted on being kept directly informed about the POW situation. Some members of the British House of Commons even began whispering that “the troubles of Kŏje-do would probably never have happened if the prison camps had been under British control.” Many British officials were privately “scathing on the subject,” although they did their best to hide their disdain publicly.84

It was only months later that Clark realized the full extent of the “civil war” and general lawless conditions that had existed at Kŏje-do. There were whisperings that Dodd and Colson had been unfairly scapegoated and that Ridgway and Van Fleet deserved much of the blame. But the anticipation of an imminent truce meant that the POW problem was largely soft-pedaled in the hope that a quick armistice would resolve all the problems. Any public revelation of the conditions at Kŏje-do, it was thought, would give the communists another excuse to delay the talks. The irony is that the armistice did not resolve the problems at Kŏje-do. Rather, the situation at Kŏje-do complicated the problem of reaching an armistice. The Dodd affair and everything that it revealed about the conditions of the camp had seriously compromised the principle of non-forcible repatriation. It gave the communists fodder for refusal based on claims that the screening process had been unfair. By May 1952, the war seemed to have reached a moral and physical stalemate. It would take a new American president to move the struggle forward, even at the risk of a nuclear war.