5 From #Ferguson to #FalconHeights: The Networked Case for Black Lives

The Black Lives Matter movement not only relies on new technological infrastructures and potentials, it was birthed in the public consciousness by them. In the tradition of Ida B. Wells’s The Red Record, a hundred-page pamphlet describing the horrors of lynching faced by Black American communities in 1895, those working to tell stories of extrajudicial anti-Black murder have turned wholeheartedly to using public platforms.

In an age of digital media, globalization, and smartphones, the power of the dogged journalism Wells inspires has moved beyond individual Black journalists and African American publications to everyday people. As we have detailed throughout this book, social media spaces, Twitter in particular, have given ordinary people the power to report stories as they unfold and to contextualize these stories within marginalized experience and knowledge. Yet it is not enough for stories to be told. They must also be heard, and to be heard they must cross online and offline boundaries and silences, reach new audiences, and move on old and new media platforms.

Alicia Garza’s first digital utterance of #BlackLivesMatter occurred on Facebook in 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman. Yet it was the extrajudicial murder of Black people, particularly at the hands of police officers, in the years following that ushered in the uprising that made #BlackLivesMatter activism an unavoidable issue for mainstream journalists and politicians.

#FergusonIsEverywhere: The Matter of Black Life Goes Mainstream

After he shot dead eighteen-year-old Michael Brown on August 9, 2014, officer Darren Wilson alleged that the teen, having been stopped for “walking in the street,” had reached through his car window and attempted to grab his gun and then charged him. Tiffany Mitchell, who saw the events unfold, said that Brown had his hands up and was begging Wilson not to shoot.1 Her account was supported by other eyewitnesses, making “Hands up, don’t shoot” a rallying cry and symbolic gesture that protesters later used to signal their outrage and resistance. Other accounts from neighbors and Brown’s friend Dorian Johnson also contradicted Wilson’s version of events, and community members quickly began to post live tweets and images from the scene. As Brown’s body was left by officials to lie in the street for over four hours, concerned community members moved in to monitor police and take stock of the horror occurring outside their front doors. Between the 2012 slaying of Trayvon Martin and that of Brown in 2014, Twitter had updated its display features, allowing pictures shared through the platform to be visible without viewers needing to click on a link.2 This practice increased the number of images shared on the site and directly contributed to the spread of pictures associated with the slaying of Brown. The second most tweeted image among those tagged with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was that of Brown lying dead in the street as Wilson stood over him.3

As an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice later confirmed, the Ferguson Police Department had a long history of misconduct in its treatment of the residents of the town. Brown’s death proved to be the last straw for a community laboring under pent-up discontent.4 Following a candlelight vigil the day after Brown’s death, a standoff between police in full riot gear and mourners boiled over, with police firing tear gas and discharging smoke bombs in an attempt to disperse the crowd. In the next days, a growing group took to the street in protest of Brown’s death and the police response to protesters. Officials attempted to create and enforce a curfew and limited the areas where protesters could gather, further agitating them. Over two weeks, the nation watched cell-phone videos and pictures shared on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites through the hashtag #Ferguson of a growing uprising and the draconian attempts to squelch it. Some journalists on the ground painted a sympathetic picture of the protests, calling into question the standard negative portrayals police used to frame the unrest.5 With time, major news outlets began to question the necessity of the militarized police force as mourners and members of the press were arrested and the now iconic images of young and old protesters facing down tanks and tear gas went viral.6

As Deen Freelon, Charlton D. McIlwain, and Meredith Clark documented in their work with the Center for Media and Social Impact, in June 2014, a year after Zimmerman’s acquittal for the murder of Trayvon Martin, there were only forty-eight posted #BlackLivesMatter tweets. In August of that year, following the killing of Michael Brown, use of the hashtag “skyrocketed to 52,288.”7 Analyzing nine time periods from 2014 to 2016, these researchers found six distinct groups of users engaging the hashtag: Black Lives Matter activists, the leftist hacktivist group Anonymous, conservative Twitter users, mainstream news outlets, Black celebrities, and young Black Twitter users, whom multiple works have shown to be an essential demographic.

According to Jelani Ince, Fabio Rojas, and Clayton A. Davis, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was used largely in five ways: to garner solidarity or approval of the movement, to reference police violence, to mention movement tactics, to talk about Ferguson specifically, and last, to express countermovement sentiments.8 They note the importance of “distributive framing” made possible by hashtags whereby evaluation of the problems and potential solutions discussed by way of the hashtags does not primarily originate with specific movement leaders. This ability of decentralized networks to eschew hierarchy is particularly helpful in spreading messages to diverse groups. Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa support this claim, reporting that #Ferguson allowed observers of the hashtag to see what “protesters were tweeting, what journalists were reporting, what the police was announcing, and how observers and analysts interpreted the unfolding events. You could also learn how thousands of users were reacting to the numerous posts.”9

As we find elsewhere, the story of what happened in Ferguson began to circulate on Twitter, first through personal accounts from Brown’s neighbors, whose tweets set the stage for how the larger activist narrative around the events of August 9 would evolved.10 The story was pushed along, and the network enlarged, by members of the local and national Black public sphere, including local alderman Antonio French, who was arrested while participating in the protests, and rapper Tef Poe, as well as MSNBC’s Goldie Taylor, a St. Louis native, and Johnetta Elzie and DeRay McKesson, who credit the events of Ferguson with turning them from concerned young citizens into activists. Together these Twitter users helped spread the story to a range of networks, documented on-the-ground efforts, and buoyed calls for aid from the general public as justice continued to be waylaid. Soon, increasing online attention to the events in Ferguson, and particularly the conflicts developing around unarmed protestors, journalists, and police, became unignorable even in the most mainstream of spaces.

#Ferguson also became more than a geographic descriptor of the town where Michael Brown was killed. It became a stand-in for Anytown, USA. Black Lives Matter activists across the country and the world were soon chanting, “Ferguson is everywhere” in demands for justice in the extrajudicial abuse and killing of Black people. The diverse conversations in, and uses of, the hashtag mirror what we have seen in both the intersectional hashtags created by Black feminists and the other hashtags that emerged after Ferguson. Ordinary people using #Ferguson and #BlackLivesMatter contributed issue framing, prescriptions, and analysis in the network that extended far beyond the digital realm to penetrate national and international discourse.

For example, in acts of solidarity, Palestinian activists used the hashtag #Ferguson to share with Ferguson activists remedies for tear gas exposure and the inhalation of smoke from smoke bombs, as well as strategies for countering police escalation tactics.11 Like the iconic images of Bull Connor’s police dogs attacking Black protestors in a segregated Birmingham, Alabama, the images and tweets from Ferguson allowed a counternarrative to emerge that exposed the racist underpinnings of responses to the protests. The most tweeted image during the August unrest signaled by #Ferguson was a side-by-side comparison of police officers in riot gear standing opposite 1960s civil rights protesters and a hauntingly similar image of police officers in riot gear facing Ferguson protestors.12

After #Ferguson, the names of more Black men, women, and children became hashtags, popularized in death because of the state-sanctioned violence that took their lives; the locations of their deaths hashtagged as a sort of geography of violence and resistance; their last words, their clothing, and their loved ones digitally documented by everyday people as part of a twenty-first-century citizen-driven Red Record. These hashtags also spurred others, such as #IfTheyGunnedMeDown and #CrimingWhileWhite (which we discuss in chapter 6), that were used to critique media representations of Black victims and to point out racial hypocrisies in police response and engagement.

We Can’t Breathe

Three weeks before Michael Brown was killed and the nation became forever familiar with Black Lives Matter activists and activism, forty-three-year-old father and grandfather Eric Garner died after being put in a chokehold by NYPD officers during an arrest for selling “loosies,” or single cigarettes. As Garner lost his ability to breathe, he pleaded with the officers, “I can’t breathe,” a phrase subsequently taken up by activists and hashtagged as they demanded justice for his death.

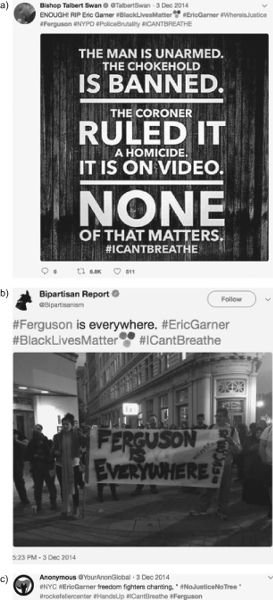

#EricGarner began trending on Twitter, with thousands of tweets containing his name appearing immediately after his death on July 17, 2014. In the days and weeks following, #EricGarner stayed visible, but modestly, as video of his death taken by his friend, Ora Ramsey, was released and Garner’s funeral was held. According to our data, the largest upticks in the use of #EricGarner began after the death of Michael Brown. In particular, #EricGarner trended in the week following Michael Brown’s death, a month after Garner’s, and #EricGarner trended most significantly after the nonindictment of the officer who choked him, which occurred simultaneously with the organized December 3, 2014, protests in response to Darren Wilson’s nonindictment for the death of Michael Brown one week earlier. In fact, most of the top tweets in the #ICantBreathe network were sent on the day of these protests, as indicated by the popular examples in figure 5.1 from Bishop Talbert Swan, the leftist news account Bipartisan Report, and Anonymous. Here we see #EricGarner and #ICantBreathe used alongside hashtags that specifically reference the events in Ferguson, such as #Ferguson and #HandsUp, along with broader movement hashtags, such as #BlackLivesMatter.

Thus, millions of #EricGarner tweets during the first week of December 2014 were in part enabled by the visibility of the Brown case, which helped activists in Long Island draw attention to the Garner case weeks and months after his July death. Together the multiplatform protest ecology whose foundations were laid in response to the killing of Oscar Grant, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, which coalesced for Trayvon Martin, and the response to the killing of Michael Brown made Eric Garner’s death not only more visible than it might have been otherwise but central to the movement. #EricGarner and his last words, #ICantBreathe, continue to trend in Twitter accounts of other high-profile cases of police brutality and with the ebb and flow of notable #BlackLivesMatter activism.

Through the use of hashtags, users link similar cases, illustrating how each is not an isolated incident but rather part of a system of violence enacted against Black people. Among the top fifteen hashtags most commonly co-occurring with Eric Garner’s name in our data were the names of other victims of police violence, including, in descending order, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, John Crawford, Freddie Gray, and Walter Scott. These connections are also rendered visible in the most frequently shared links in the hashtag networks. In #EricGarner tweets, the link that appeared most often was a 2016 Instagram post by actress/singer Zendaya that read, simply, “Another day … another hashtag. …”13 Posted nearly two years after Garner’s death, Zendaya’s caption on the image reads, “#EricGarner #SandraBland#OscarGrant #AltonSterling #WalterScott#PhilandoCastile to think … that’s not even the beginning of it, these are just the few we got on video … makes me sick.” Like others who digitally connected similar cases through hashtags that came before, we see Philando Castile, the most recent case on Zendaya’s list, linked to a hashtag narrative that begins with #EricGarner.

Figure 5.1

Examples of hashtag co-occurrence in #EricGarner and #ICantBreathe tweets.

After Ferguson: The Ongoing Evolution of Black Lives Matter Networks

Following the summer 2014 police killings of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, the news media began reporting regularly on similar cases. While some perceived an uptick in police brutality as a result of this coverage, similar events are old news in communities on the front lines of the militarization of local police forces and entrenched race and class biases. Yet new technologies used by activists, the increasing power of ordinary people to influence the news cycle, and the mainstream attention that has resulted from the cases of Oscar Grant and Trayvon Martin to those of Michael Brown and Eric Garner have created a renewed (or for some Americans, a brand-new) interest in instances of state-sanctioned anti-Black violence.

Among the most notable cases in the period from 2014 to 2017 in addition to Garner and Brown are those of twenty-two-year-old John Crawford III, who was killed by police in a Walmart store outside Dayton, Ohio, while holding a BB gun he had taken off the store’s shelf; twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, who was shot and killed by Cleveland police officers while playing with a toy gun on a playground; fifty-year-old Walter Scott, who was shot in the back and killed during a daytime traffic stop in South Carolina; twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray, who sustained life-ending injuries during an excessive force arrest and “rough ride” by Baltimore police; twenty-eight-year-old Sandra Bland, whose suspicious death in a Texas jail after a routine traffic stop we discussed in depth in chapter 2; thirty-seven-year-old Alton Sterling, who was shot at close range by Baton Rouge, Louisiana, officers responding to a complaint that he was selling CDs on the street; thirty-two-year-old Philando Castile, a beloved elementary school staffer who was shot by police in Minnesota during a traffic stop, with his girlfriend and her toddler in the car; twenty-three-year-old Korryn Gaines, who was shot while holding her five-year-old son by Baltimore police serving a traffic warrant; fifteen-year-old honor student Jordan Edwards, who was shot in the back by a Dallas, Texas, officer who opened fire on a car of unarmed teens; and thirty-year-old Charlena Lyles, who was pregnant when she was shot by Seattle police after calling them to respond to an attempted burglary at her home.

This macabre list is nowhere near the full number of African Americans killed by police during the period but only a sampling of the highest-profile cases Americans learned about, often first through Twitter and other social media outlets and then from the mainstream media. Below we examine the network and discourse trends of three of these cases in addition to the work we have previously discussed on #TrayvonMartin (chapter 4), #SandraBland and #SayHerName (chapter 2), and #Ferguson, #MikeBrown, #EricGarner and #ICantBreathe as part of the larger narrative and demands of the Black Lives Matter movement.

#TamirRice (2002–2014)

On November 22, 2014, the weekend before Thanksgiving, police in Cleveland received a concerned call about someone with a gun on a playground. “It’s probably fake,” the caller said. Two officers responded and, according to reports, shot twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, who was playing with a fake gun, within two seconds of arriving on the scene.14 He died the next day.15

The hashtag #TamirRice trended almost immediately, with thousands of tweets appearing November 23, 2014, and over a million tweets during our one-year data collection window (November 22, 2014–November 22, 2016). The top co-occurring hashtags in the #TamirRice network speak to the interconnectedness of the cases discussed here amid larger #BlackLivesMatter activism. In addition to #BlackLivesMatter and #Cleveland, the other most popular hashtags in the network are the names of victims of anti-Black violence, including #EricGarner, #MikeBrown, #SandraBland, #TrayvonMartin, #FreddieGray, and #JohnCrawford.

At the root of #TamirRice tweets are mournful, angry, and often desperate questions of innocence. Who, these tweets ask, has access to the benefit of presumed innocence if a child on a playground does not? What is justice, they proclaim, in the case of a child murdered by the state? These tweets offer specific critiques about the ways anti-Black racism denies childhood—both experientially through a lack of perceived innocence and literally through death—to Black children. These tweets tell a story about how familiar the African American community is with violence against innocents and the intergenerational grief and rage that exists in response to the state treating Black children’s lives as disposable rather than precious.

For example, one widely shared tweet in the network bemoaned, “A 12 y.o. With a toy gun. A child. With a toy. Killed. For no reason … other than the fear of Blackness. Even in childhood … #TamirRice.” Another observed, in response to a CNN story on the shooting, “White kids don’t have to worry about being killed at the playground because of a toy gun & I hope they never do. #TamirRice #Ferguson @CNN.” Activist Shaun King tweeted, “I don’t say this lightly but #TamirRice is the closest thing to #EmmettTill we’ve had in this generation”—a comparison that was also applied to Trayvon Martin. Filmmaker Ava DuVernay’s one-word, one-hashtag tweet, “Innocent. #TamirRice,” which was shared and liked almost 20,000 times, speaks to the resonance of discourses of innocence in the network.

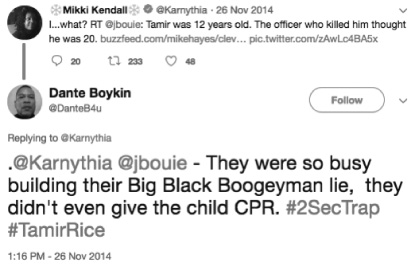

In an example of how influential members of the networks we have examined throughout this book overlap with journalists and ordinary people in the larger #BlackLivesMatter network, African American journalist Jamelle Bouie (@jbouie) shared a story about the officer who killed twelve-year-old Rice reporting that the child was twenty years old, to which Mikki Kendall (@Karnythia) of #FastTailedGirls expressed exasperation and various other Twitter users responded by noting the ways in which Black children’s lives are neglected because of racism. These kinds of exchanges are common throughout the #BlackLivesMatter networks, with both central and peripheral members of the Black public sphere playing varied roles in reporting on, reacting to, and organizing around anti-Black violence, all in the context of a sometimes unspoken indignation about the details of these cases.

#FreddieGray (1989–2015)

On April 12, 2015, Freddie Gray, like many young Black men who have reason to fear the police, ran when he encountered Baltimore officers. The officers chased him down for “flee[ing] unprovoked when noticing police presence,” though later would use Gray’s possession of a knife found after the chase as the reason for arresting him.16 Witnesses reported that officers aggressively forced Gray to the ground, bending his legs at an unnatural angle. Once loaded in the police wagon, Gray was subjected to what is infamously known in Baltimore as a “rough ride,” in which officers purposely stop short, drive erratically fast, and turn corners sharply to cause discomfort to the arrestee in the wagon. Because Gray was not secured with a seat belt and was handcuffed and could not steady himself, he sustained a serious spinal cord and brain injury that resulted in a coma and his death a week later.

Figure 5.2

Filmmaker Ava DuVernay’s tweet on Tamir Rice the day a grand jury declined to indict the officer who killed him.

Mikki Kendall’s reaction to Jamelle Bouie’s reporting spurred comment from less high-profile followers of the two online.

With Gray’s life slipping away on April 18, hundreds of protestors surrounded the Baltimore Police Department’s Western District precinct to demand information about the circumstances leading to his injuries. The protests continued for several days, even as the police department erected barriers to limit access to the precinct. On April 25, thousands of protestors marched from the Western District precinct to City Hall to demand justice for Gray’s death. Later that evening, a fight broke out between some attendees of the protest and patrons of a nearby bar. During that clash, several young men smashed the windows of a police car, resulting in a widely circulated photograph of protesters standing on a Baltimore police car, with the superimposed text, “All HighSchools Monday @3 We Are Going To Purge From Mondawmin To The Ave, Back To Downtown #Fdl” (sic), an apparent reference to the 2013 movie The Purge, in which lawlessness ensues following the legalization of all crime for a twelve-hour period in a fictionalized, dystopian United States. In response to what they claimed was a credible threat, on April 27, the day of Freddie Gray’s funeral, the Baltimore Police Department proactively shut down a shopping mall and metro station in the Mondawmin area, leaving nearby high school students stranded at the end of the school day. The details of events immediately following the students’ release from school are contested, with some reports suggesting police officers accosted students who were peaceably assembled and others suggesting students initiated a confrontation by throwing rocks and bricks at officers. In the hours and days that followed, unrest escalated and spread throughout the city, resulting in significant property damage and dozens of arrests as students and protesters were met with a violent police response. Local political leaders declared a state of emergency, called in the National Guard, and instituted a citywide curfew, effectively ending the protests on April 28.

The hashtags #BaltimoreUprising and #BaltimoreRiots alongside #FreddieGray make this network unique as they reveal the explicit awareness and debate by Twitter users of two competing narratives about the protests. While critiques of police violence and racism levied with hashtags like #Ferguson and #ICantBreathe were sometimes challenged by those seeking to justify police use of force or demonize victims of police violence, attempts at hijacking those hashtags for discourse that might undermine the Black Lives Matter movement was largely drowned out on Twitter by the popularity and frequency of tweets reinforcing the movement’s message.17 In contrast, #BaltimoreRiots and #BaltimoreUprising both trended during the protests and offered competing accounts of events as they unfolded.

While #BaltimoreRiots was the first to be adopted by the network, activists and community members soon observed that the hashtag was being used to frame protestors as violent, unreasonable, and uncivilized—popular tropes used to represent and undermine Black rage in the wake of oppression and neglect.18 For example, in the #BaltimoreRiots network, popular @FoxNews tweets overwhelmingly focused on “violent riots,” “looting and burning,” and the “state of emergency” in Baltimore, using sensational language like “totally insane” and “cops led into slaughter” to describe the conditions on the streets during the unrest. In this framing, Fox News described events in militaristic language that placed protestors in the position of powerful and dangerous enemy combatants, characterizing police as “outnumbered and outflanked.” In response to such narratives, many in the network shifted toward using the #BaltimoreUprising hashtag with which they reported from the ground in Baltimore about the protests. In the Gray case they offered narratives legitimizing Black rage and contextualizing urban uprisings. Popular members of the #BaltimoreUprising network framed the community’s eruption after the death of Freddie Gray as part of a righteous struggle. @Deray described the protests in Baltimore as “organized struggle” in his tweets and frequently commented on the “beautiful sense of community” in Baltimore, describing meetings between protestors and Baltimore clergy and the distribution of snack bags to protestors by volunteers. McKesson also highlighted the work and experience of “peaceful protestors.” Likewise, fellow activist Johnetta Elzie (@Nettaaaaaaaa), who became well known, like McKesson, for her work in Ferguson after the killing of Michael Brown, frequently tweeted about solidarity protests that were occurring around the country in response to events in Baltimore and tweeted photos of protestors holding signs reading, “It is civil disobedience that will give us civil rights” and “Not a riot a revolution.”

Users tweeting with hashtags #BaltimoreRiots and #BaltimoreUprising more commonly interacted with others using the same hashtag, creating a polarized network structure. But tweets incorporating both hashtags and conversations between those using different hashtags were not uncommon. Those who rose to prominence among people using both hashtags included stokers, who, in response to contested discourse signaled by the competing hashtags, held fast to the ideological polarization of their preferred hashtag and often shifted to more extreme versions of the messages represented on each side of the polarized network. For example, while #BaltimoreRiots was frequently attached to implicitly racist messages about rioting and looting, the #BaltimoreRiots stokers made explicitly racist comments about Black neighborhoods, Black families, and, tangentially, President Barack Obama.

In contrast, a second set of prominent users were brokers, who used both hashtags to engage with those who differed in their understandings of the Gray case and the resulting unrest. Brokers engaged in conversations across the polarized network, clarified misunderstandings, and provided informational content about the protests as they unfolded and the broader history and policy concerns that contextualize urban unrest as a symptom of racist structures and policies. Ultimately, thanks to these brokers it was the critical “uprising” frame that most helped the #FreddieGray network proliferate and that became most visible on Twitter as a mourning and angry community demanded answers and justice in the Gray case.19

#PhilandoCastile (1983–2016)

On July 6, 2016, Philando Castile was pulled over in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, in an apparent case of racial profiling following a bank robbery in the area. Castile, who worked at a nearby elementary school, was accompanied by his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, and her four-year-old daughter. After disclosing to the officer that he had a registered firearm in the car and explaining to the officer that he was reaching for his license, Castile was shot seven times. Reynolds began livestreaming on Facebook in the aftermath of the shooting, pleading with the blood-covered Castile to “stay with me,” and attempting to talk down the officer while comforting her four-year-old daughter. This video was viewed and shared on social media sites millions of times.

On Twitter, news of Castile’s death spread quickly, with more than a million tweets containing his name appearing on July 7, 2016, alone. In just one week, #PhilandoCastile was tweeted more than two million times. Many of these tweets either shared Reynolds’s shocking Facebook Live video or referenced it. For example, one user’s popular tweet sharing the link reported, “The original video was taken off of Facebook, so here it is. #PhilandoCastile #FalconHeightsShooting,” and included a now defunct hyperlink to an archived version of the video. Similarly, activist Shaun King tweeted, “#PhilandoCastile was the brother shot by police in the Facebook Live video. He died tonight,” with a link to the developing story on the local Minnesota CBS affiliate, and radio personality Alex Gervasi shared a link to the video, noting, “The video keeps getting taken down. Keep it spreading. #FalconHeightsShooting #PhilandoCastile.” Here we see how overlapping social media infrastructure and networks were used to draw attention to and build outrage around the case. While Twitter, at that time, had no live video streaming capabilities, linkages across Facebook and Twitter not only allowed Reynolds’s video to spread rapidly but also helped preserve it even as it was removed from one platform or the other. Seven years after the cell-phone video of Oscar Grant’s murder by police in Oakland was posted to YouTube and shared with news networks, the shifts in technological capabilities, and the overlapping uses of these technologies, are clear.

Other popular tweets about #PhilandoCastile openly pointed out the hypocrisy of gun rights advocates who insist on the right to conceal carry but who were silent on an innocent Black man being murdered by an officer who felt threatened after being informed that there was a permitted gun in the vehicle. For example, one popular tweet in the network offered, “I want @NRA to defend #PhilandoCastile and #AltonSterling. Let’s go, y’all. Second Amendment sanctity and the whole bit. Go. Now,” connecting Castile to another recent case in which police justified shooting Alton Sterling at close range because they believed he had a gun in his belt. The call on the National Rifle Association (NRA) to defend Black men who are ordinary citizens and gun owners as rigorously as they defend the Second Amendment is a rhetorical and ironic request, in light of the organization’s history.20 Likewise, @MamaBKrayy tweeted, “#PhilandoCastile told officers he had a permit to carry BEFORE they murdered him. Where is the #NRA to defend him and his rights??” These calls remained popular in the network over the course of our data collection, including after the June 2017 acquittal of the officer who killed Castile and larger public debates and events about guns, the NRA, and the Second Amendment. For example, the science fiction author Patrick S. Tomlinson tweeted in response to an NRA TV spot that denigrated the Black Lives Matter movement, “An @NRA that cared about the rights of gun owners would have raised hell over #PhilandoCastile’s murder.”

Users also mourned with, praised, and expressed concern for Diamond Reynolds and her child, who were in the car with Castile when he was shot. In particular, people remarked on the devastating cool with which Reynolds filmed the murder of her partner and efforts to manage an unimaginable situation. Some users noted the lifelong trauma Reynolds and her daughter will have and used the hashtag to discuss the impact of anti-Black state-sanctioned murder not only on those whose lives are ripped from them but also on the surviving family members and communities who experience such traumatic loss. These tweets focused particularly on the inhumane behavior of police to not only kill Castile but also to victimize his partner and her child. A popular user, for example, reported, “#PhilandoCastile bled to death. No cops tended to him. Instead they cuffed his girlfriend. #FalconHeightsShooting.”

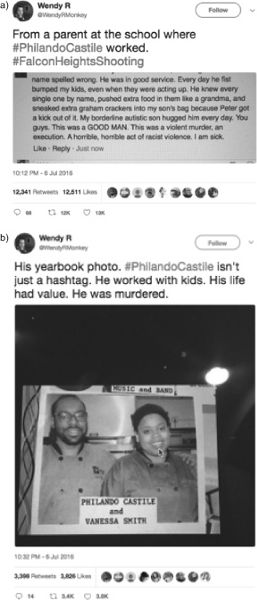

Finally, the hashtag was used to celebrate and commemorate Castile, particularly as a beloved educator and friend of children. For example, the tweets below from Minnesota resident @WendyRMonkey, who shared a screenshot of a mournful Facebook comment from a parent of a boy Castile worked with at the J. J. Hill Montessori Magnet School and a smiling photo of Castile with a colleague in the school’s yearbook, were shared thousands of times. While these commemorative tweets initially appeared on local accounts close to Castile’s community, as the network expanded and time passed, their tone was picked up by advocacy accounts and other national users. For example, an account that was started to promote and document the 2017 Women’s March protests in response to the inauguration of Donald Trump also regularly tweets about various social issues and advocacy concerns. In July 2017 the organization helped organize and promote an action called #NRA2DOJ, in which it pressured the NRA and the Department of Justice to speak out against and take more action on police profiling and gun violence against Black people. As part of this, @WomensMarch shared a commemorative hyperlapse video of artist Demont Pinder’s rendering of Castile, tweeting with it “A powerful tribute to #PhilandoCastile by @DemontPinder caught in hyperlapse at today’s #NRA2DOJ vigil.”

Shaping Change for Black Lives

In tracing these cases of anti-Black state-sanctioned violence, the Twitter networks they inspired, and the discourse that made them visible in mainstream America, we see important shifts in the visibility of racial justice issues in America. From the time of activism around the killing of Michael Brown in 2014 to the killing of Philando Castile in 2016, just two short years, our data reveal several important trends.

Figure 5.4

Commemorative #PhiladoCastile community tweets.

First, we see the birth of “celebrity activists.” Some Black activists, such as DeRay McKesson and Shaun King, became quite visible because of their on-the-ground or discursively compelling tweets during a particular protest. They continued to occupy central roles in subsequent protest networks as individual Twitter users and mainstream media outlets looked to them as sources. This centering of celebrity activists in online and offline spaces undoubtedly helped spread discussions of anti-Black state-sanctioned violence into the mainstream, but it is not uncontroversial. From within movement ranks, Black Lives Matter cofounders Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors and others in allied organizations have critiqued the importance and capital heaped on outside figures like McKesson and King by media-makers and politicians who do not understand the movement’s leadership or offline organizing practices. To further complicate matters, some celebrity activists fail to correct media-makers for misattributions of leadership, and others engage in actions that do not appear to fully align with the spirit of the movement. For example, King was accused of (and vehemently denied) embezzling funds he had helped raise in support of families of victims of police brutality, and New York activist Hawk Newsome drew the criticism of other Black Lives Matter organizers when he took the stage at a Trump rally to explain the Black Lives Matter platform.21 Many of the figures who have claimed or had bestowed on them the mantle of leadership in the movement are men, even though the founders and many organizers central to Black Lives Matter and the coalition Movement for Black Lives are women.

Of course, the widespread reach and distributed organizing of the various networks taking part in Black Lives Matter discussions online make it possible for many different voices to rise to prominence, which means that no single person or group of people is representative of the whole movement. Mainstream news outlets continue to appear confounded by this organic and diffuse leadership structure and often either appoint leaders and find spokespersons for the movement or deem it unorganized and leaderless. Movement historian Barbara Ransby, however, has noted that Black Lives Matter functions similarly to the vision of the Black Freedom Movement espoused by civil rights organizers like Ella Baker, whereby organizers “help everyday people channel and congeal their collective power to resist oppression and fight for sustainable, transformative change.”22 Likewise, Black Lives Matter cofounder Patrisse Cullors has described the movement as not leaderless but rather “leader-full.”

Other shifts in networked discussions of cases we have explored in this chapter reflect the changes in attention and newsworthiness with which stories of racialized police violence have been treated in recent years. In the two years that elapsed between the deaths of Michael Brown and Philando Castile, there was a marked shift in the type of news organizations appearing as influencers in each network, from the regional, alternative, and specialty news sources that first covered Ferguson to the larger mainstream outlets, such as CNN, that played a central role in conversations following Philando Castile’s death. Thus we see that the early frames, issues, and demands of Black Lives Matter activism moved from ordinary people and media connected to them to the moderation of mainstream news media. This mainstream attention is important as it draws more Americans into conversations about police profiling and racial violence. Yet it also poses a danger for activists as since 2012, and especially since 2014, law enforcement bodies have developed increasingly sophisticated ways of tracking Black activists organizing online—a continuation of the anti-Black surveillance documented by such scholars as Simone Browne.23

In the end, it is important for activists and ordinary people in these networks to read and give firsthand and community-specific accounts. As the #FreddieGray network reveals, mainstream newsmakers and representatives of the state continue to fall back on narrow and often stereotypical representations of African American communities, their issues, and their activism—something Twitter activism actively resists.

Relatedly, we see a shift in the range of users’ racial identities within these networks. From the Trayvon Martin case (discussed in chapter 4) and the Michael Brown case to more recent cases like that of Philando Castile, network influencers transitioned from being primarily African American—both ordinary people and celebrities—to including an increasing number of white people, both ordinary and celebrity. This suggests, just as the measurable shift of these stories into mainstream media does, that sustained and compelling #BlackLivesMatter activism around various cases succeeded in drawing in new supporters and communities. Those not directly affected by the issues appear, through social media networks, to become better versed in raising and discussing issues of racial inequality.

In a nod to how timely conversations about Black Lives Matter have become to media-makers, Time magazine used African American photographer Devin Allen’s 2016 photo of a Baltimore protestor running away from police to consider “What has changed. What hasn’t” since the 1968 uprising in the city following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.24 As if inspired by the comparative side-by-side photos from the two eras that ordinary people tweeted during protests in Ferguson, Baltimore, and other cities, the cover, on one of the most widely circulated news magazines in America, seemed to acknowledge that, despite claims by some that the United States had entered a “postracial” era, some things are very much the same.

Time magazine cover featuring photograph by Devin Allen.

In popular culture, Black Lives Matter cofounders Cullors, Garza, and Tometi were honored at the 2016 annual Black Girls Rock Award show broadcast on VH1, and Black and white celebrities have taken up Black Lives Matter issues on- and offline. NFL Quarterback Colin Kaepernick famously took a knee during the national anthem in a silent protest against police brutality, a move that led to his Blacklisting by the NFL but has since inspired countless other NFL players and professional athletes to do the same or to speak out on the issue despite public censure from President Donald Trump.25 White actor Matt McGorry, best known for his roles in Orange Is the New Black and How to Get Away with Murder, live-tweets from Black Lives Matter protests he attends. Women athletes from college basketball to professional soccer players have also been outspoken on the issue.26 With considerable team solidarity and eventual league support, WNBA players remain steadfast in their demonstrations for Black life.

In February 2016, the Fraternal Order of Police in Miami announced a national police boycott of Beyoncé tour dates because of the Black Lives Matter “themes” in her halftime performance at the 2016 Super Bowl and in the video for her song “Formation,” which features her atop a partially submerged New Orleans police car and a wall with the graffito “Stop shooting us.”27 Such examples illustrate the reach and impact of the movement on politics, popular culture, and everyday life in the United States.

In this chapter we have illustrated the profound ways hashtags emerging before and after Ferguson were infused with life because of connections, overlaps, and co-occurrence in the network that functioned both to build a timeline and context for anti-Black state-mediated violence and simultaneously to insist on justice in every case, even as time passes. In this regard, Ruha Benjamin (discussed in chapter 2) and Kashif Jerome Powell have made the case that not only do Black lives matter, so do Black afterlives, as evident by the reanimation of such hashtags as #EricGarner and #ICantBreathe long after the events to which they refer moved into the past, as well as the ability of these hashtags to incite protests that propel a movement forward. Powell has argued that the specters of these hashtagged Black lives have “transitioned from flesh to force,” compelling a search for justice by those who survive.28