I am a child of Chatham.

I grew up in black segregated Chicago. Not in a neighborhood decimated by the 1968 riots, blight, poverty, white flight and boarded-up buildings. My South Side black cocoon was a solid black middle-class neighborhood. Judges, teachers, lawyers, doctors and city, postal and social workers live in Chatham. The neighborhood has an assorted housing stock: ranches, Georgians, sturdy bungalows, bi-level chic midcentury moderns. An unusual showstopper mansion, modeled after the White House and built with robin’s-egg blue bricks imported from Italy, stood on display around the corner where I grew up. Our family of five lived in a four-bedroom brick Cape Cod with an unfinished basement prone to flooding. The lower level had dark wood paneling, a bar and milk crates crammed with dusty records from my parents’ era—from a Redd Foxx comedy album to the Ohio Players to Malcolm X’s The Ballot or the Bullet.

When we were growing up, ice cream trucks jingled in the summertime. We girls jumped Double Dutch rope—despite my occasional double-handed turns—on the sidewalks in front of our homes. We rode our ten-speed bikes to buy Jays Salt ’n Vinegar potato chips, Now & Later candy and dill pickles at the nearby Amoco gas station. We rotated having crushes on David, who lived around the corner and rode his bike incessantly up and down the streets. Pajama parties meant Jason and Freddy horror flicks on loop. We avoided the loose Doberman pinschers that would escape the gate of that big blue mansion. We jumped through lawn sprinklers in our swimsuits in backyards while our parents barbecued. We played makeshift baseball in the alley with tennis racquets. We blew out candles on pound cakes at our birthday parties. We had the kind of dramatic childhood fights that resulted in the silent treatment or smack talking. Posters of Michael Jackson, decked out in his yellow “Human Nature” sweater, decorated our bedroom walls. We walked the track and swung on swings at Nat “King” Cole Park, named after the Chicago-born crooner. The park’s basketball courts hosted some of the city’s best street players in the 1970s and 1980s. Former Illinois U.S. senator Roland Burris lived around the corner from our house (in gospel powerhouse Mahalia Jackson’s former residence), and he exemplified the cliché “It takes a village” by cajoling my parents to let me attend his alma mater, Howard University.

In our backyard, before the term “organic” entered the mainstream culinary lexicon, my dad harvested vegetables. On Saturday mornings, my younger brother, sister and I pulled weeds to clear the way for him to plant cucumbers, zucchini, carrots, bell peppers, collard greens, eggplant, tomatoes and radishes. Every year he gently reminded me that Chicago weather wouldn’t allow him to grow my favorites—watermelon and strawberries. My mother drove a red Camaro for the better part of the 1980s. Not fire-engine or candy-apple red; more like the color of smeared red lipstick.

It would be years before I realized that I grew up in kind of a cozy racial cocoon of black middle-class vivacity in a city otherwise torn by racial division.

My parents, Joe and Yvonne, were first-generation college graduates and South Side natives. Joe, a Vietnam veteran who worked at Shell Oil Co., first as a marketing manager and later as an area diversity veep, represented the post–civil rights wave of African Americans hired by Corporate America. He never shaved his mustache and liked to say “It’s Nation Time, time for all black people to stand up and be counted,” in his version of middle-class militancy. Yvonne, with her pageboy hairstyle and freckles sprinkled across the bridge of her nose, taught special education/home economics at a public school two blocks from our home. It sometimes embarrassed me when her students recognized me walking with friends in the neighborhood. “Hey, are you Miz Moore’s daughter?” As a child I looked so much like her, she joked that I sprang from her forehead like Zeus’s daughter.

My grandparents—one who didn’t make it past third grade, another a Pullman Porter turned Playboy Mansion bartender—moved to the South Side during the Great Migration, which lured blacks from the South to the land o’ milk and honey up North. They worked hard, bought houses, two flats and later rental properties and sent their children to college.

My own immediate family mirrored The Cosby Show—to a degree. Sitcoms always sanitize life, right? And decades later, we know this television show was an artifact of the times, a fallacy constructed by the eponymous patriarch whose reported sexually predatory offstage life casts a shadow on his art. But our world brimmed with similar middle-class black families rooted in black identity. We were neither special nor an anomaly in Chicago. But the Cosby label stuck. In 1986, at the height of Huxtable fever, the Chicago Sun-Times did a feature story on local black and white families drawn to the transcendent television sitcom. A friend of a friend recommended our family, and a reporter and photographer came to watch the show at our house and afterward peppered us with questions. I was ten, my brother Joey, seven, and sister Megan, five. The article noted that my little sister bubbled like young Rudy Huxtable. But when she disobeyed my mother twice during the interview, Mommy quipped, “What would Clair Huxtable do?” Everyone laughed.

During the interview, my dad wore his corporate work uniform—crisp shirt and patterned, but not too flashy, with a tie. This was unusual; he always changed into sweats when he came home after his long suburban commute. Naturally, we children snickered and questioned him when he only removed the suit jacket that evening. He explained that he had to give a positive image of black people to the news media. The blanket Chicago South Side image in many white minds equals pathological ghetto. Reporters often enable that stereotype by only covering crime when they deign to venture to the South Side. Daddy was a man who went to work every day, provided for his family and wanted to project that image for readers of the newspaper. He was simultaneously routine and radical.

This existence embodied what being a child of Chatham was like. The ideals and values of the civil rights generation found a place to live. In the tradition of being a good, upstanding Negro, my dad wanted to present a positive image in the news media by showing how we lived accordingly in black middle-class-dom.

Blacks started moving into Chatham after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racially restrictive housing covenants in the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer decision. Once confined to the city’s “Black Belt,” African Americans finally could choose where they wanted to lay claim to the American Dream. Upwardly mobile blacks started moving into Chatham in the 1950s with their own aspirations after white families fled, faced with the specter of so-called outsiders.

The founders of the Luster hair care company lived in Chatham. The Johnson Products Company plant—makers of Afro Sheen—operated on the outskirts, as did the iconic Soft Sheen. The black-owned Baldwin Ice Cream had a shop near our house. Black-owned banks operated in the neighborhood. Catholic, Baptist, Presbyterian and A.M.E. churches boasted strong memberships. I didn’t know “Ay-rab” wasn’t a word until I attended college. Some Arab merchants, who lived outside of Chatham, owned stores in the neighborhood and had unsavory reputations of bad business practices and poor service. An Arab-owned, full-service grocery store that opened a few blocks from our house went out of business because the community refused to support it. Shoppers complained about the service and low-quality food. In my household, my father drilled into us not to shop at that store or patronize non-black-owned small businesses in Chatham. Honestly, it wasn’t that hard; we had black dry cleaners, hair salons, barbecue joints, barbershops and soul food restaurants.

Everyone on our block knew each other and looked out for one another. Mr. and Mrs. Strong’s granddaughter Aisha and I met at age seven. She lived in Philadelphia but spent every summer in Chicago. Aisha introduced me to Prince’s first album, For You, and told of the bombing of the black liberation group MOVE in her hometown. Each spring I counted on Mrs. Lee to order a box of Thin Mints to support my Girl Scout troop. Mr. Henderson’s family owned a popular shoe store. Mr. Montgomery retired from the Chicago Police Department. Mrs. Smith always kept her long silver hair knotted in a bun and tended to a sweet dog named Chug who rarely barked. Her son Brian went to school with actress Jennifer Beals. Three doors down, the Nolans owned an auto body shop, and every Fourth of July fireworks erupted during their backyard parties. Mrs. Peterson’s daughter Pam and her bestie, Zenobia, gave me and my friends makeup lessons. A few blocks over I met Brandi at a young age; our fathers attended college together. She and I devoured books and discussed the likes of Gloria Naylor and the insipid Sweet Valley High series around her kitchen table.

Lest I construct Chatham as a black urban Mayberry, my father also instilled in us his self-efficacy. He volunteered with the Chatham Avalon Park Community Council. At his behest, my siblings and I canvassed the neighborhood putting flyers for community meetings in mailboxes. This level of activity protected Chatham’s legacy. Residents attended block meetings and police community gatherings and knocked on the city council member’s door. The neighborhood endured its share of crimes: robberies, break-ins, muggings and assaults. When I was in high school, an ominous “Chatham rapist” haunted the neighborhood. On more than one occasion, thieves broke into our garage and stole the tires off of my dad’s 1984 brown Chevy Bonneville company car. In 1981, just days before Megan was born, my mother discovered our Great Dane, Caesar, dead in the basement laundry room. Blood dripped from his mouth as a result of rat poisoning. To this day, my father believes Chicago police officers did the deed in retaliation for him reporting them sleeping on the job nearby in a squad car. Daddy and his nephew loaded the dog’s body in a wheelbarrow to be picked up in an alley by whomever you call to dispose of animal carcasses. A thief stole the empty wheelbarrow.

Chicago boasts miles upon miles of black neighborhoods with high rates of home ownership. In South Shore, the Jackson Park Highlands district is a designated Chicago landmark, home to gorgeous architecture, the stately houses displayed on oversized grassy lots. Over in Pill Hill, the lawns are all so perfectly manicured it appears as if all the homeowners use the same landscaping company. Roseland may be one of the most troubled neighborhoods in the city, but a tiny affluent section has Tudor homes with Mercedes-Benzes in the driveways. Burnside, Avalon Park and Washington Heights are examples of uneventful, middle-class communities with single-family bungalows, ranches and frame homes.

Black middle-class neighborhoods are not immune from urban ills. As Chicago sociologist Mary Pattillo writes in Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril Among the Black Middle Class, the black middle class is not the same as the white middle class. Black middle-class neighborhoods are characterized by “more poverty, higher crime, worse schools and fewer services than white middle-class neighborhoods.”1

At a time when the number of annual murders in Chicago was notably high, my parents fretted that Joey would fall into the hands of gang recruiters. Parental love and opportunity don’t always protect black boys. A mile from our house, national high school basketball phenom and Chatham native Ben Wilson was gunned down across the street from his school in 1984; then age eight, that’s my first memory of violence.

Crack may not have choked Chatham, but one neighbor on our block became addicted. I learned my first street lesson bike riding solo on 83rd Street. I was 11 years old and about to roll past a group of unfamiliar teen boys. The worry rumpled my face like a piece of wrinkled clothing. I was scared of getting jumped. As my wheels squeaked by, one of the teens said to me, “If you look scared, you get jumped.”

Chatham may have been the beginning of my world, but it never confined me. On the heels of integration, a yellow school bus ferried Joey, Megan, and me to a public elementary school in another South Side neighborhood called Beverly. Little did we know we were part of desegregated busing. By age 11, my neighborhood friends Donna, Brandi, Aisha and I ignored the closest mall on 95th Street and ventured downtown or to swanky North Michigan Avenue via public transportation. In high school, we ambled about in North Side malls and eclectic pre-gentrified neighborhoods, such as Wicker Park, to browse clothing, book and record stores. I unconsciously knew that Chicago’s blacks, whites, Latinos and Asians generally didn’t live together. I certainly never saw any non-blacks living in Chatham. But growing up in segregation felt like air and water—a constant, but something I never pondered until a small incident upended my detachment.

* * *

It was a hot summer day in 1990. Donna, Brandi, Aisha and I boarded the Chicago Transit Authority “L” train from downtown and headed back to the South Side to get dressed for an evening of dreamboat loveliness. We were 14 years old with tickets to see R&B crooner and New Edition front man Johnny Gill at the New Regal Theatre on 79th Street. I seriously crushed on him and had made my own fan button.

An easy visual clue to Chicago’s segregation is watching who boards and exits the “L.” Back then white people emptied off by downtown. A few intrepid riders may have stayed on until the Chinatown stop at 22nd and Cermak. But on this particular day, the white folk stayed on and packed the train shoulder to shoulder past 22nd Street. Talk about baffling. Yes, the South Side is synonymous with blacks, and yes, whites and Latinos live in ethnic enclaves in the city’s largest geographic swath. But no way did this throng of white Chicagoans live off of my “L” line. Why was I so shocked? I felt my world pivot. I wasn’t scared or angry, just disoriented.

Then, at 35th Street, all of the white riders unloaded from the train cars: the stop for Comiskey Park, the White Sox baseball stadium. Crisis averted! Mystery solved. Absolute relief. My little world was pieced back together, but that’s when segregation became real to me.

* * *

I celebrate my upbringing. Chatham molded me. The environment nurtured me. A rhapsody in blackness. It’s such a delicious reversal of privilege and entitlement that caused me to feel territorial in a space like public transportation.

But I understood the racial lines and demarcations of Chicago. I knew something was amiss in my neighborhood. There were fewer places to shop, and crime and poverty were closer. In my adult years, I realized that for all of their uplift and efficacy, black middle-class neighborhoods are by nature precarious. They aren’t ghettos, but they exist because of segregationist housing policies designed to create ghettos. When housing opened up across the city and redlining wasn’t as prevalent, white flight ensued. Black middle-class neighborhoods do their best to thrive in impossible, ugly circumstances. But like black ghettos, the black middle class, too, complains about policing, city services, investment and amenities.

By definition, the black middle class equates to the white lower middle class in America. Many white Chicagoans have no idea that a place such as Chatham exists and couldn’t pinpoint it on a map. Everyday black middle-class life is invisible in America. People going to work, sending their children to school, living their lives, minding their business. When studying segregation, researchers typically concentrate on the urban black poor underclass. The black elite are more visible with the election of Barack Obama and his inner circle of friends coupled with familiar faces like Oprah. In a graduate school journalism policy class I took at Northwestern University, a professor rented a bus to give students a tour of different parts of the city. She let me narrate part of the South Side, and when we drove around Chatham my white peers gaped, remarking how the neighborhood looked better than some white areas. They were shocked and awed.

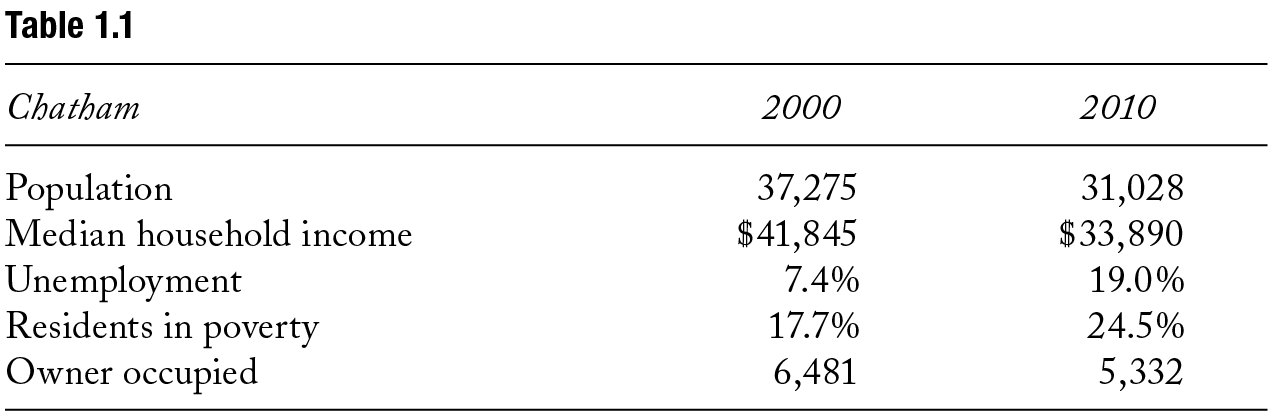

Chatham has long enjoyed an independent streak—namely by not voting for Mayor Richard M. Daley—and mightily protecting its black cocoon. The economic crisis and housing collapse that began in 2008 tested the limits of black efficacy and excellence, and Chatham continues to fight for its legacy. Although white flight is in the past, home values and investment reveal current fragilities. Research indicates that black wealth barely exists and black middle-class kids are downwardly mobile.2

The term “middle class” is hard to define in the United States. It’s aspirational and nebulous, and people in a range of incomes, from low to upper, consider themselves in that social stratum. Social scientists measure income, occupation, education and wealth. Northwestern University sociologist Mary Pattillo told me, “Given those somewhat objective measures, basically what we find is on any one of those measures, the black middle class is smaller and somewhat more disadvantaged than the white middle class.” For example, about 37 percent of whites have a college education, compared to 18 percent of blacks. Further, middle-class blacks are clustered in lower-class occupations, such as sales and administrative work, while whites are clustered more in higher-earning white-collar occupations.3 Meanwhile, the backbone of the black middle class has been in the public sector—teachers, social workers and municipal jobs.

“Black middle-class neighborhoods across the country and surely in Chicago have two faces to them,” Pattillo said. “I call this the privilege and the peril of the black middle class. The privilege comes with these being homeowners. Some of those perils are the result of racial segregation. We’re thinking about Chatham situated within the larger South Side.” That means higher crime and poverty rates and proximity to underperforming schools.

“I don’t want to say all people in general are bad influences or living next to poor people is a peril in of itself. But there’s no question that when you have higher poverty rates, you have fewer disposable resources, for example, for families to spend on businesses, for families to spend on institutions,” Pattillo explained.

In a ten-year span, from 2000 to 2010, Chatham coped with massive change. The economy, housing values, median incomes and cultural clashes with newly arrived public housing residents affected the neighborhood in stark ways. Those residents moved to Chatham on subsidized housing vouchers after the city demolished their buildings.

* * *

My parents bought the Cape Cod Chatham house in 1974, the year they got married. Their search for a home never strayed from the South Side since they were both natives. The pretty homes, postage-stamp lawns and stability drew them to Chatham. Instead of a big-production wedding, my parents exchanged vows at City Hall, my mother outfitted in a minidress, and they used their savings for a down payment on the house, which they bought for $30,000 from an older widow, a stranger who quickly became fond of my father. For a couple ready to start a family, the house was perfect: a basement, family room extension and two-car garage. Once settled in the house, they held a belated wedding reception to which my mother wore a three-piece ivory silk pantsuit.

“Chatham was a neighborhood of excellence. It was a no-brainer,” my father reflected about their decision.

“Chatham was just really the neighborhood of choice,” my mother chimed in. “It was the black neighborhood, very stable middle-class neighborhood. Professional blacks and working people lived there too.”4

They planted a metaphorical red-black-and-green flag. Immediately my father volunteered with the block club and greater neighborhood association. “If you wanted to live in a nice community, you had to be a part of maintaining that nice community. If you want good property values, you’ve got to have good people involved with the same values.”

By the time my parents moved to Chatham, there were about as many whites in the neighborhood as one would find at a Louis Farrakhan revival.

But Chatham’s origins actually go back to white immigrants—and it’s a story similar to other black South Side neighborhoods. Many of them started off white.

In the late 1800s, Italian stonemasons and Hungarian and Irish railroad workers inhabited Chatham, which is about ten miles from downtown. The population quadrupled when new Swedish and other immigrants moved in during the 1920s, firmly shifting the neighborhood from working to middle class. When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racially restrictive covenants in 1948, black families exited the hemmed-in borders of the Black Belt. Some went to Chatham, and whites quickly decamped. Some families moved in the middle of the night. In 1950, Chatham was 99 percent white. In 1960, its white population had dropped to 36 percent. By 1970, only 0.2 percent of the population was white.5 White families didn’t like the idea of living harmoniously next to black folk. Sometimes real estate agents ushered them out by playing on their fears that “the blacks” were coming. Racially motivated vandalism occurred; for example, in 1956 someone shot out the windows of gospel singer Mahalia Jackson’s home.

Chatham maintained its middle-class character as the population shifted from white to black. And in our household, as well as in others, one of the unofficial mantras was to “buy black.”

“We bought our gas in the community. We went to the cleaners in the community. We got our hair cut in the community. I would take the family on Sundays to dinner at restaurants like Army & Lou’s and Izola’s, and that’s where we used to see Mayor Harold Washington with his bodyguard eating dinner. We tried to support the black businesses in the community,” my dad said.

My parents never worried about a black cocoon limiting their children’s existence and experiences in the 1980s. All the while, several events shaped Black America, a time when the post–civil rights era was in full effect. The Reagan era stripped cities of sorely needed federal dollars. At the same time, crack flooded the streets, spiking urban violence and renewing the so-called War on Drugs. A conservative backlash blamed black people for problems in black neighborhoods—ignoring segregation and turning back the clock on civil rights, such as when President Reagan vetoed the 1988 Civil Rights Bill. Historically black colleges saw dips in enrollment as black students applied to other institutions. Black Entertainment Television (BET) launched. The Nation of Islam rebooted and tapped into racial pride. Hip-hop matured with protest messages. Michael Jackson enticed us to all sing together. In Chicago, voters elected the city’s first black mayor in 1983. Oprah brought her folksy talk show persona to the local ABC affiliate and syndicated it in 1986. Jesse Jackson Sr. pursued the White House twice.

“We did a lot of things outside of the neighborhood,” my mother said. “I remember I would take the three of you on the ‘L,’ and I had some friends that would say ‘You took public transportation?’ But it was a way to show you more of the city, and you were exposed to different things other than this black middle-class neighborhood. Sometimes parents don’t want to expose their kids to what they call ‘the element.’ And I never really felt that way. And I think with the attitude Joe and I had, we believed all people were equal and we didn’t make a whole lot of class distinctions—at least I hope I didn’t.”

It’s hard to make strong class distinctions in middle-class black communities because the definition is more elastic. In those areas, subsidized housing exists, as do multi-unit apartment rental buildings. And despite their higher incomes, black homeowners pay the cost of racial segregation.

“The black tax is more crime, and goods and services cost more. I remember grocery shopping in the neighborhood and when I wanted to pay by check I had to almost get out my birth certificate. I stopped going there,” my dad explained. He went to the same chain in a white area on another occasion and wrote a check. “I never even had to show my driver’s license. They didn’t ask me any of the other things I had to go through. And their prices were lower.”

Criminality loomed too.

“There was some crime [in Chatham], but nowhere near the kind of crime . . . as there was in other parts of the city. As the result of the solidarity in our community, we were not hit as hard with crime—and maybe because of the economics; the economics were a little better there,” he said.

My mother recalled a spate of robberies targeting older women in broad daylight as they walked from their garages into the house.

Black neighborhoods tend to be class heterogeneous, a mix of poor, working and middle class. The iconic, picturesque images and ideals of Chatham can’t always insulate the neighborhood from crime or lack of services/amenities. Compounding that experience is the fact that, plainly put, home ownership keeps black poorer than whites. The Chathams of this country suffer from good ol’ fashioned racism. When these neighborhoods turned black after whites left, resources fled too. Negative racial impressions strengthened because blacks “invaded” white space. It doesn’t matter if black neighborhoods score high marks on the typical things white middle-class families look for in their home search. According to Gregory Squires’s 2007 study for the American Academy of Political and Social Science:

Evidence indicates that it is the presence of blacks, and not just neighborhood conditions associated with black neighborhoods (e.g., bad schools, high crime) that accounts for white aversion to such areas. In one survey, whites reported that they would be unlikely to purchase a home that met their requirements in terms of price, number of rooms, and other housing characteristics in a neighborhood with good schools and low crime rates if there was a substantial representation of African Americans. The presence of Hispanics or Asians had no such effect.6

My father spoke of a “black tax.” It’s real. Public safety concerns and higher-priced goods in black neighborhoods equate to what’s dubbed a black homeowners’ “segregation tax.” According to the Brookings Institution, black homeowners receive 18 percent less value for their homes than white homeowners. Typically, black homeowners in metropolitan areas in the Midwest are subjected to a higher segregation tax than in other parts of the United States. Homeowners in black neighborhoods don’t actually pay the government in cash with this tax. “‘Tax’ in this context can be considered similar to the high domestic prices for sugar and steel that result from import quotas and tariff barriers—what are often characterized as a ‘tax’ paid by American consumers,” the 2001 Brookings report says.7

The reduced equity for homeowners in highly segregated neighborhoods reflects the impact of past and current public policies. Black isolation propagates the cycle of inequity. Conversely, home values in poor white neighborhoods are higher than in poor minority neighborhoods. Homes in black neighborhoods are poor long-term investments because it’s difficult to build equity in them since they are valued lower: the more segregated an area, the wider the black/white gap in home value per dollar of income; the less segregated an area, the narrower the gap. According to Brookings, the worst metropolitan areas for the segregation tax besides Chicago include Buffalo, New York; Milwaukee; Baltimore; Detroit; Philadelphia; Gary, Indiana; Ft. Lauderdale–Hollywood–Pompano Beach, Florida; and Toledo, Ohio. The best include Boston; Providence, Rhode Island; Honolulu; Tulsa and Oklahoma City; and Albuquerque, New Mexico.8 The antidote to better housing values is stable integrated neighborhoods.

We’re taught that home ownership is a requisite for accessing the American Dream. For black families, that idea can be a cruel joke.

Emory University professor of tax law Dorothy Brown knocks down this wealth-building American Dream premise. “Historically, this is how wealth has been built in the white community. This is not how wealth has been built in the black community,” Brown told me. The home ownership market works differently if you’re black. According to Brown, if a neighborhood is more than 10 percent black, the value of the home goes down. “Most whites want to live in homogenous white neighborhoods. They don’t want to live around lots of blacks. And I define lots of blacks as 10 percent.”9

People in all-black neighborhoods aren’t necessarily aware of the financial consequences associated with buying a home in a majority-black neighborhood. They may be first-time homeowners lost in a reverie of black picket fences.

“I would argue part of the reason we have this racial wealth gap is because most Americans have most of their net worth tied up in their homes, and if you’re white and you’re living in a predominantly white neighborhood, that’s actually not a bad financial thing to do. If you break it out to race, you’re going to see far less equity in black homes. It’s worked for whites; it hasn’t worked for blacks,” Brown told me.

Brown isn’t advocating that people shun diverse or even black neighborhoods when buying a home. Rather, she advises people not to put all their eggs in the home ownership basket but to invest in the stock market, mutual funds and retirement accounts. Her message is especially haunting, given that the housing collapse wiped out a generation of black wealth.

* * *

In academic parlance, Chatham qualifies as a middle-market neighborhood—stable, majority owner occupied. It’s also the kind of neighborhood where block clubs are visible before you step on a street. Black South Side neighborhoods are riddled with welcoming signs plopped on corners announcing their presence plus instructions for what not to do: for example, no loitering, no drugs, no car washing or loud music. These messages, perhaps even read as conservative, disrupt rampant stereotypes about blacks tolerating disorder in their communities.

The 1990s onward brought a flush of cash and capital to places like Chatham that had been starved for decades. Then, in 2008, all of that crashed. Hard.

“The foreclosure crisis cannot be underestimated, and the way it has been particularly concentrated in black neighborhoods is not at all random,” sociologist Mary Pattillo told me. “We shouldn’t . . . say that the housing crisis just happened to be black neighborhoods hardest hit. It didn’t happen that way at all.

“We have lots of data that show that black families making the same amount of money and the same amount of credit risk as white families were still disproportionately sold [more] subprime loans than white families. And that has devastated the black community in terms of wealth possession and in terms of now-vacant boarded-up homes. It’s opened up increased renters. In areas with high home ownership, that undermines the kind of block club mentality that many of these neighborhoods have fostered over the decades.”

In 2013, Illinois attorney general Lisa Madigan and the U.S. Department of Justice announced a $335 million settlement with Bank of America after suing its subsidiary Countrywide for abuses, discrimination and misconduct that led to discriminatory lending in African American communities and contributed to the financial crisis. From 2004 to 2008, approximately 15,000 black and Latino Illinoisans were steered into subprime loans and charged higher interest rates and fees on mortgages than their white counterparts.

University of Illinois at Chicago professor Phil Ashton examined the transformation of neighborhood housing markets and the challenges of recovery. Chatham was one of the three South Side neighborhoods studied that “are also ‘stuck’ with potentially long-term ramifications resulting from concentrated subprime lending.” Many homeowners were left underwater, meaning they owed more than the value of their houses. In the mid-1990s, the bulk of lenders in Chatham were Federal Housing Administration loan products and small savings banks. Conservative underwriting standards of the day kept home buying relatively steady. According to Ashton, however, from 2004 to 2007, large mortgage companies specializing in subprime lending were responsible for most of the Chatham loans.10

Another important element differentiates the black middle class from its white peers: The black middle class is newer and just starting to get into the second and third generation. A person new to the middle class may have grown up poor and as a result foots the financial obligations of their parents, who may not have money to keep up with bills. In addition, a person new to the middle class would not have had parents to help with a home down payment or a college education. The recency of the development of the black middle class compared to that of the white middle class contributes to the fragility of the former.

According to Gregory Squires, who wrote the 2007 American Academy of Political and Social Science report on racial discrimination, in housing markets, 28 percent of whites receive an inheritance averaging $52,430 compared to 7.7 percent of blacks with an average bequest of $21,796.11

Barack and Michelle Obama—pre-presidency—symbolize the fact that race trumps class even for this upper-middle-class family. Dorothy Brown, the Emory University professor, analyzed the Obamas’ tax returns from 2000 through 2004 in a paper titled “Lessons from Barack and Michelle Obama’s Tax Returns.” Their combined annual income fluctuated; the lowest was $207,647 on their 2004 tax return, and the highest was $272,759 on their 2001 tax return. With that level of income, the Obamas did not resemble their financial peers, who are disproportionately white. They more closely resembled their racial peers, who disproportionately have much lower incomes. And in their investments, the Obamas appeared more like households earning less than $100,000, because they didn’t diversify their portfolio in the stock market.

The South Side Obamas, who lived in Hyde Park, paid more in taxes than their financial peers. There are several explanations for this. The couple had lower itemized deductions than their higher-income financial peers. And there are two race-based explanations: the marriage penalty and stock ownership.

“As a result of their household income levels, the Obamas would have been subject to significant marriage penalties if either spouse contributed close to 50 percent of household income,” Brown wrote in her analysis, and continued:

Michelle [contributed] an ever-increasing amount of household income. For each year, however, the Obamas are subject to the greatest penalty because the lower-earning spouse contributes between 40 and 50 percent. In 2002 Michelle Obama contributed 43.67 percent of wage income to the household. In 2003 she contributed 48.63 percent to the household. In 2004 Michelle Obama contributed 58.80 percent to the household. Between 2002 and 2004, the median contribution to household income by wives was approximately 35 percent. . . .

Black wives have historically worked outside the home more than white wives. . . . Married black couples were more likely to pay a penalty than married white couples, largely because married black husbands and wives were the most likely to contribute roughly equal amounts to household income.

The second potential reason why the Obamas paid higher taxes than their financial peers is because of their lack of stock ownership and income eligible for capital gains treatment. During the examined tax years, the Obamas received no capital gains or dividend payments. According to Brown:

Tax Policy Center data for 2005 indicate that greater than 75 percent of all capital gains and dividend income flows to households with income above $200,000. According to IRS data from 2003, the percent [sic] of capital gains and dividend income as a share of all income is 1.4 percent for the average household making less than $100,000. For households making between $200,000 and $1 million, this income accounts for 12.2 percent of total income. Again, the Obamas do not resemble their financial peers—they appear more like those households making less than $100,000, which is less than half of their household income. . . .

While many may assume that once blacks earn more money, their stock ownership will mirror that of their equal-earning white peers because they believe stock ownership is a class issue, the Obamas’ tax return data proves that assumption to be false. Higher household income has not allowed the Obamas to transcend race.12

* * *

Chicagoans cling to neighborhood identity, and for many of its residents, Chatham is a state of mind. The foreclosures, subprime lending and recession weren’t the only influences threatening the collective efficacy for neighborhood stability. Crime has always been an issue in Chatham—even if traditionally it has been lower than in other black neighborhoods—but the media glare and perception of lack of safety have changed how the neighborhood is widely viewed.

“Unfortunately, predominately black neighborhoods in Chicago, whether poor, working class, or middle income, have always faced spatial vulnerability to crime to an extent that white neighborhoods of all kinds simply have not,” writes Robert Sampson in Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect.13

In recent years, there has been an uptick in robbery and aggravated battery in Chatham. The causes are drugs, fragmenting gangs, stores illegally selling loose cigarettes, muggings outside of bars.

In 2010, the murder of an Iraqi war veteran in front of his parents’ home shook the neighborhood, and the story reverberated around the city. Thirty-year-old Thomas Wortham IV—whom my brother and sister knew as children—was an off-duty police officer shot to death. He died on the street he grew up on. On the fatal night, he was about to leave his parents’ home on a motorcycle when two men tried to steal it.

Given the distress of crime, Sampson wonders whether Chatham will “become the newly truly disadvantaged as the black middle class flees, more houses are foreclosed, and poverty rises with the influx of families displaced by the city’s [public] housing authority?” The answer, he discovers, is no. “The data tell a story of resistance to crime, challenge-inspired collective efficacy, and a long-term stability to the area in its social character, despite underlying structural vulnerabilities.” Sampson defines “collective efficacy” as the process of activating or converting social ties among neighborhood residents to achieve goals. According to his research, Chatham ranked second in collective efficacy among black Chicago neighborhoods and ranks eighth in the entire city.14

Fighting for a legacy shouldn’t be so hard when the community is engaged. Chatham residents attend community policing meetings—when blocks are calm and when blocks are hot. Block clubs abound, as do local community groups. One example is the Chatham Avalon Park Community Council.

Council president Keith Tate’s family moved to predominantly white Chatham in 1955. His father loved the neighborhood so much that he convinced his sisters to buy nearby. Then his aunt and uncles on both sides of the family bought too. The tight-knit community led Keith Tate to return to the neighborhood to raise his own family.

“One of the biggest challenges is the lack of continuity and connectedness within the community,” Tate told me.15 He’s not harkening back to a mythical Mayberry existence of back-in-the-day stories. A real problem in Chatham is that it’s an aging community—not with vibrant senior citizens but with people in their 80s and 90s who either no longer can contribute to neighborhood efficacy or have moved to senior facilities and left their homes to children not as invested in the property.

Tate recognizes that fear cripples the neighborhood. “Now we have what is called a fear complex. Parents are afraid to let their kids come out and play, afraid to take them to the parks, afraid to let them cross the street—which is an ideology they brought to this community,” he said. “It’s a perception, and in some cases, your perception is your reality.”

Monthly community meetings, supporting small business owners and cultivating relationships with police officers are standard practices for Chatham. Tate told me that a marketing blitz must be done to attract families to the historic bungalows—and not just black families. Even though I believe that Chicago segregation can’t continue as it is, I was surprised to hear a dedicated Chatham leader take such a view on race when the identity of the neighborhood has been so wrapped up in blackness.

“We’re marketing to nonblacks because the nonblacks that come through the community, they look and say to me ‘Oh, these people don’t know what they have,’” Tate said, referring to cheaper housing prices compared to areas of the North Side. And economically, Tate said, the presence of other races could help retail development.

A New Form of Redlining

Bridget Gainer is a white North Side politician who grew up on the South Side. She’s a Cook County commissioner and chair of a local land bank formed to address the overwhelming inventory of vacant property.

When she talks about places like Chatham, Gainer puts into perspective the changing needs of residents in changing neighborhoods. It’s not a sexy, hip neighborhood on the edge of downtown but instead a silent victim of the financial crisis.

“There might be vacancies, but people are cutting their neighbor’s grass and they’re taking the papers off of the porch and making it so you can’t really tell that it’s vacant. The vacancies aren’t really driven by crime so much as it’s driven by an aging population. Those are the things I think about when I think about Chatham because to some degree, it’s a victim of its own success. It was such a stable place that produced so many successful people. But like lots of neighborhoods, you’re not getting the same kind of return, of people moving back there and still having some of those things that still bring people there in the first place,” Gainer told me.16

The land bank acquires some of that vacant housing, holds it, makes sure it’s safe and then finds developers to rehab it for a reasonable amount of money. The land bank clears the red tape on taxes and water bills, and it tries to find alternative lending products for buyers.

But the whole financial meltdown gave Gainer a different view on how the system isn’t working. “The whole appraisal system in my mind got totally upside down, and that’s a massive area for reform. You could argue there’s quasi redlining when it comes to appraisal,” she explained. For example, how can a suburban appraiser understand a black Chicago neighborhood when that person knows nothing about the community and may bring the baggage of stereotypes? You wouldn’t use an uninformed realtor so why use an uninformed appraiser?

“Everyone’s afraid of overestimating the value of homes; they’re lowballing their estimates. So you saw that appraisers started to overcompensate for mistakes they made in the past but because there was greater scrutiny on evaluations, you started to get this really wide and unconnected group of people doing appraisals who may not have a lot of community knowledge. And so the appraisal system I think was fatally flawed,” Gainer said.

This idea dovetails with the work of Dorothy Brown, the Emory University professor. She said racism could consciously or unconsciously be embedded in how appraisers value properties when they are in black neighborhoods. Brokers play a crucial role too. “Brokers decide what neighborhoods to send their clients to. If a broker thinks that showing black prospective homeowners a house in neighborhood X is going to annoy the neighbors, then the broker’s not going to do it. The broker works for the neighborhood and the broker wants more referrals.”

Brown laughed as she told me her radical idea for upending the way home ownership functions around race. “Let’s reconfigure the mortgage interest deduction. Let’s not allow it across the board. We know there’s this racial disparity and the impact of home ownership based on the percentage of black neighbors you have. We know it’s not a level playing field. Why don’t we use the tax deduction to disrupt it?

“Why don’t we say no one gets a mortgage interest deduction unless they live in an integrated neighborhood? We realize you’re taking a penalty in the market, and we want to compensate you by lowering your taxes.” If your neighborhood is 10 percent or more black, you get the deduction, Brown explained.

Brown thinks this plan could work because the Constitution says you can’t take account of race except when you can show intentional discrimination. For her, the government’s past policies on home ownership, such as the Federal Housing Administration’s redlining practices, should qualify as discrimination. The government allowed redlining to take place in black neighborhoods by not offering home loans and helped subsidize the growth of the suburbs in the mid-twentieth century.

* * *

In the fall of 1996, my junior year of college, I called home for a regular check-in. I asked my mother what she was doing. “Packing,” she replied. “Where are you going?” I asked, assuming she was taking a trip. “We’re moving,” Mommy answered.

Silence.

“Moving where?”

“To Beverly.”

Silence.

Tears.

Click.

Yes, I had a flair for the dramatic. I overreacted because I couldn’t say good-bye to the home I grew up in. Come Thanksgiving, I’d be in a new house. In my immaturity, I focused on waves of nostalgia and attachment to Chatham. I was silly and selfish. My siblings had their own reactions. Joey, then a senior in high school, was upset about leaving his friends. Megan, a sophomore, had more friends in the new neighborhood and could walk to high school, unlike my brother.

For years my parents had house hunted in Beverly, a family-friendly South Side integrated neighborhood with a gorgeous and bigger housing stock. It’s the area where we Moore children attended a public elementary school through a busing program. I figured house hunting was a hobby. Some couples play cards; others golf; mine spent several years dropping by open houses. I never took seriously their desire to move beyond what they referred to as a starter home. My father explained that it was a bigger house with a bigger backyard—although I still had to share a room with my sister when I visited.

“I miss Chatham. Chatham is my first love,” my mother admitted. “We just wanted a larger home.” It’s about one and a half times bigger, with two family rooms and many more bathrooms.

“We should’ve moved earlier. We had outgrown the house but we were so committed to the community,” my dad added.

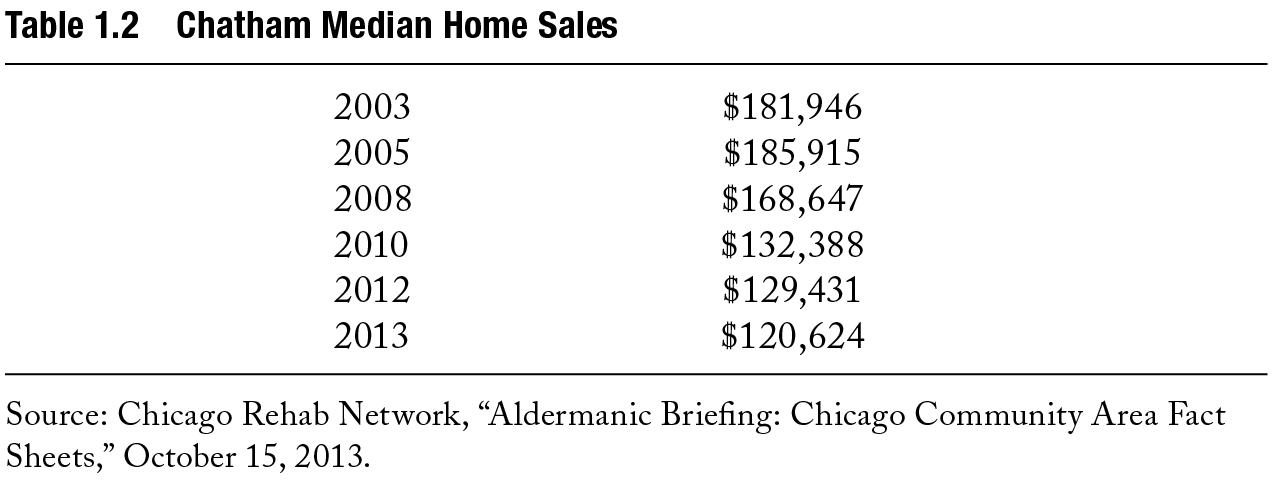

A decision based on square footage turned out to be a sage financial move. Moving to an integrated neighborhood provided my parents a long-term cushion, as the research of Emory professor Dorothy Brown indicates. In 1996, they sold the Chatham home for $130,000, clearing close to $100,000 in profit that they put into the new house, which was just shy of $300,000. Nearly 20 years later, the Chatham median home sale price is $129,000 as the neighborhood scales out of the postrecession haze. Of course, if my parents had stayed, the house would’ve been paid for, but the 2008 housing collapse would have undermined their investment and demolished their nest egg. They bought in the South Side Beverly/Morgan Park area, which is about 60 percent white. That house is now paid for. No obvious foreclosures or board-ups mar the neighborhood. The area is safe and residents take pride in its village feel.

According to Brown, homeowners pay a price for living in an area 10 percent or more black. There’s also an integration penalty. Edison Park is a neighborhood comparable to Beverly. It’s about as far north as Beverly is south. In 2010, 34 blacks out of more than 11,000 people lived there. Beverly’s median income is higher, but its median home sale price at the market’s peak was about $40,000 lower.17

My 20-year-old self moved on from the emotional attachment of Chatham, and I’m happy that, in quasi-retirement, my parents made prudent financial decisions. The home is a source of family joy for backyard July 4 barbecues, Christmas by the fireplace and weekend afternoons when my dad fires up the grill for cheese-stuffed hamburgers and roasted vegetables.

It took me years to realize how smart my parents were.

I am one of the people who didn’t return to Chatham. When it was time for me to buy in 2008, I wanted that hip, sexy new thing. I was single and didn’t want a house. I ended up buying in an area formerly known as the Black Belt, a move that turned out to be a financial bust for me.

I, too, am now part of the black ownership cautionary tale.