On a March morning in 1962, Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley dedicated a spanking new public housing high-rise development on the South Side. The Robert Taylor Homes shined—clean buildings, polished elevators. In a lobby ceremony, Daley presented keys and flowers to tenant James Weston, a 32-year-old married glass inspector and father of two.

“This project represents the future of a great city,” the powerful mayor intoned. “It represents vision. It represents what all of us feel America should be—and that is a decent home for every family in every safe community.”1

Indeed, the Robert Taylor Homes contrasted with the previous housing in the Black Belt. Families up from the Great Migration often lived in slummy, overcrowded one-room kitchenettes—cut-up, run-down, fire-gutted structures.

Taylor replaced those slums and became the world’s largest public housing development with 28 buildings and 4,300 units, stretching nearly two miles. On that winter morning in 1962, the high-rises symbolized new opportunities for black families yearning for suitable affordable housing.2

Decades later, jackhammers flattened the last Taylor tower to a pile of rubble. Over the years, the high-rises had morphed from housing two-parent working families to housing unemployed single mothers and became a playground for vicious gangs and open-air drug markets. Government and housing officials branded Taylor a national failure, emblematic of mammoth social problems. Unemployment soared, public assistance provided income for the majority of families and the poorly managed buildings decayed.

In time, policy makers engineered a second slum clearance. In 1999, the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) devised the ambitious and controversial $1.5 billion Plan for Transformation, a blueprint to deconcentrate poverty by rehabbing or developing 25,000 units across the city. The man responsible for the biggest public housing redevelopment program in the country happened to be Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley, the son of Richard J. Daley.

The latter Daley received special permission from Washington, D.C., to tear down the high-rises and construct new mixed-income communities that assembled poor, affordable and higher-end households under a banner of unity on the very footprint of the former projects. In 2008, the mayor stood in front of Parkside of Old Town—a North Side development that replaced Cabrini-Green public housing—flanked by public officials, cameras and residents. “When I said I was going to do this, most people thought that I lost my mind. Someone said ‘why are you going to do this—it’s the federal government, nothing’s going to change. People don’t want change there.’ But I said to myself when you drove through the city and public housing was on one side of the street, the other housing on the other . . . why is it that we always look to the other side and never look to public housing?” Daley stated.3

The Daleys, father and son, have a public housing legacy wrapped in symbolism. One built the high-rises. The other tore them down. Both ceded to political pressures of how and where to house poor black people, and by so doing affected tens of thousands of public housing families. But essentially both men perpetuated the ruthless cycle of segregation. The Plan for Transformation allowed only a small percentage of families to move back to their original communities in those new mixed-income neighborhoods. Thousands of families were relocated with subsidized housing vouchers to live in poor, underresourced black neighborhoods—the antithesis of the plan’s expressed goal.

The vertical segregation of the high-rises mutated to horizontal segregation.

* * *

Lobeta Holt was one of the last residents to leave one of the remaining Robert Taylor buildings in 2002.

She moved in at age 18 and left at age 30.

“I loved it. It was like a home to me. People respected me. You could knock on the door and ask for sugar and bread, and it was like a family,” Holt, 41, told me wistfully.4

Holt had a rough childhood in which she was bounced around homes. She struck out on her own at 14, when she had her first child. As much as she laments about the good ol’ days at Taylor, life demanded a lot of negotiation, including convincing drug dealers and gangbangers to leave her sons alone.

In the 12 years since her Taylor building closed and our interview, the mother of seven lived in five apartments on her subsidized housing choice voucher—commonly known as Section 8—around the South Side.

At first CHA denied Holt a voucher under a one-strike rule because of a drug charge against her then-14-year-old son. Authorities dropped the charges, and Holt says CHA tried moving her into two other CHA properties. Holt rejected those choices because one was too far, isolated at the city’s southern edge, and the other wouldn’t have been safe for teenage boys vulnerable to street gangs. Under pressure and a looming deadline, Holt says she regretfully selected the voucher as her final CHA housing choice.

“I let them [the CHA service provider] really convince me. I am real weak when it comes to talking to somebody,” Holt said.

Each apartment in which she used a voucher presented a barrage of problems: failed inspections, red ants biting her children, malfunctioning appliances. One of her more recent homes flooded, and she lost everything.

“Who wants to move every year or two—especially when you don’t have the money?” Holt said. She can’t remember all the schools her children attended. “They did very poor because they were so used to that school then they have to transfer. They started dropping out.”

None of her children finished high school. All but one has a criminal record.

When I visited her at her new apartment in a South Side neighborhood near the closed steel mills, Holt surveyed her sparse current living quarters. “I heard it’s a bad area to live in. They shoot. I haven’t seen it yet because I’m fresh in the hood. I don’t socialize at all. I keep to myself,” she told me. Almost a third of the residents in the neighborhood live in poverty. She moved in two weeks earlier with two of her children, ages 7 and 21.

Holt has severe asthma and is disabled. At times she’s had to breathe through a tube in her neck connected to an oxygen tank. Holt admits to psychological problems, and in 2001, she was shot at a bus stop when visiting family on the West Side.

“I drink now. I drink too much, and I’m on psych meds. I have depression, anxiety. This ain’t how I wanna live. I want a beautiful home. And a job. That’s my goal,” Holt said. “I wish I could find my dream home. I wish I could find a home where I could stay for years. I want a house with [a] big pretty yard. A home with a washer and dryer.

“I’m way over Section 8,” Holt said of the subsidized housing voucher she uses to rent.

* * *

Chicago’s public housing developments have inspired pop culture and incensed policy makers. The Near North Side’s Cabrini-Green is arguably the best known. The 1970s television sitcom Good Times portrayed a black family living there and keeping their heads above water. The acclaimed documentary Hoop Dreams followed a high school star basketball player from Cabrini. A serial killer haunted residents in the horror flick Candyman. Students from the movie Cooley High lived there too. On the West Side, journalist Alex Kotlowitz’s 1991 nonfiction There Are No Children Here heartbreakingly captured the childhoods of two brothers coming of age in the Henry Horner Homes living in the “other America.” (Oprah Winfrey turned it into a TV movie.)

Before the city’s public housing stock gained the “notorious” epithet, lofty goals gave hope to struggling families. Decades of mismanagement, bad policies and state-sanctioned segregation, however, made it a case study in how not to treat the black urban underclass.

At its inception, the CHA represented a new era of affordable housing to supplant blight. Formed in 1937 under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, CHA provided shelter for war-industry workers during World War II. Subsequently, developments served as transitional postwar housing, and by the 1950s, the agency was the biggest landlord in the city, with more than 40,000 units.

In the backdrop, other dynamics shaped the racial composition of housing around Chicago. As mentioned, some black families exited the Black Belt for some white South Side neighborhoods that opened up after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racially restrictive housing covenants in 1948. White flight began promptly, and the chance of integrated neighborhoods on the South Side greatly diminished. Public housing ended up as just one casualty of anti-integration forces.

CHA built its initial housing developments—Jane Addams, Julia C. Lathrop and Trumbull Park Homes—in white neighborhoods. Cabrini’s first buildings opened in the 1940s, replacing an Italian slum dubbed “Little Hell.” The task of integrating CHA developments met stern resistance. Angry white mobs rioted in 1948 when eight black families moved into Fernwood Homes in the South Side Roseland neighborhood.5 White Southwest Side neighborhoods protested that the mayor had the nerve to suggest that public housing welcome blacks in their community. City Hall killed any proposals to build public housing for black tenants in white wards (and to build any senior public housing, because old blacks might show up). Council members elbowed out the progressive CHA head, Elizabeth Wood, who pressed for racially mixed housing, and fired her in 1954.

A new adversary to progressive housing policy emerged when voters elected Richard J. Daley mayor the following year. He sneered at integration and famously said that Chicago had no ghettos or segregation. Daley made sure the Robert Taylor Homes were built in a black ward.

Robert Taylor himself would have been irate that the infamous high-rises would bear his name. As the first black CHA commissioner, and later chair, he served from 1943 to 1950. Taylor grew up in Tuskegee, Alabama, and earned a banking and finance degree from the University of Illinois–Champaign. He worked for black-owned banks and dedicated his career to securing home loans for blacks. Although his family lived comfortably in the Black Belt, Taylor understood the surrounding inferior housing. After joining the CHA board, he traveled throughout Europe to study public housing and subscribed to the theory that low-rises accompanied by grassy space were the best housing for poor families. Like Wood, he championed integrated housing.

However, Chicago aldermen refused to support racially mixed housing, so Taylor, feeling politically deflated, resigned from CHA’s board in 1950. He died of a heart attack in 1957. The Taylor family considered the high-rises a mockery, not a salute, to his legacy.6 (Taylor’s granddaughter is Valerie Jarrett, close friend and adviser to President Barack Obama.)

The honeymoon at the Robert Taylor Homes was short-lived, and families like that of James Weston, who received flowers and keys from Daley at the 1962 grand opening, didn’t stay long. Many scholars say the 1969 Brooke Amendment, while good intentioned, crippled public housing and pushed out families like the Westons by mandating that public housing authorities rent to the very poor, thus replacing working-class families. The law required families to pay no more than 25 percent of their income for housing; as a result, 8,000 CHA families received rent reductions in 1970.7 CHA collected less rent income, impacting operations and property maintenance.

Every decade reflected a shift in family status and income at CHA properties.

- In 1963, 51 percent of residents had two parents in the home. By 1983–1984, that number had fallen to 6 percent.

- In 1972, 54 percent of families received some sort of public assistance. By 1992, just 10 percent of families had employment. At Taylor, the rate was only 4.3 percent.8

The underground drug economy flourished in the 1970s as a substitute for the formal economy. Neglected residents watched the red-and-beige Taylor buildings deteriorate. The high-rises built in the mid-twentieth century to replace Black Belt slums had become their own slums.

Decades earlier, Elizabeth Wood had argued against high-rise housing, saying that families wanted low-rises with yards for their children. A good chunk of CHA high-rises were gallery style, meaning their exterior hallways were partially exposed to the outside, dubbed “sidewalks in the sky.” The design politics invited piercing criticism about warehousing poor families on top of one another. But high-rises aren’t inherently deleterious. Chicago’s lakefront bursts with high-rises on the North Side, and pockets of high-rises dot the South Side. The New York City Housing Authority had built high-rises for low-income families that were successful. So why did Chicago’s towers evoke anguish and surrender to a bureaucratic mess? Roosevelt University professor D. Bradford Hunt suggests that one of the misguided strategies that tripped up CHA was a seemingly innocuous one: housing too many children.

Hunt says the decision to develop projects with high proportions of apartments with multiple bedrooms to accommodate large families was a fatal error. The high-rises had higher youth–adult ratios than other public housing developments—and than other Chicago neighborhoods, for that matter—leading to social and fiscal disorder. By 1965, Taylor already had 2.86 youths for every 1 adult; in the city as a whole, the number was less than 1 youth to 1 adult. It’s not about blaming families for having too many children, Hunt explains. But the number of children living in high-rises hampered the ability of adults to mind the children, resulting in higher crime and vandalism. Pragmatically speaking, too many youths caused elevator breakdowns.9

Black children and adults in public housing lived out of the mainstream. Greater Chicago blamed them for their condition: Anonymous poor high-rise dwellers. Trifling black folk mooching off the government. Politicians and policy makers asked themselves: Where do we put poor people? Local and national pressure to solve the problem surged.

By the 1990s, Washington tired of CHA, which often was declared the worst public housing agency in the nation. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development took over CHA in 1995, citing dangerous conditions, dysfunctional management and an aging housing stock that concentrated the very poor in high-rise ghettos. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) secretary Henry Cisneros testified before a House committee that nearly half of CHA’s residents were children. “The problems in Chicago have accumulated over decades. Discrimination was part of the problem. Low-income African-American families were segregated in huge projects and deliberately isolated from white neighborhoods,” Cisneros said.10 “The architectural designs of the past, dense high-rises, contributed to the isolation. . . . Of the 15 poorest communities in the nation, 11 are in CHA public housing communities.” He vowed to turn CHA around. A year later, CHA apartments failed a national viability test, and the agency lost more than $100 million.

Richard M. Daley waged a political gamble and wrested back control of CHA in 1999. Ethan Michaeli, publisher of the Residents’ Journal, the award-winning publication produced by CHA residents, succinctly described Daley’s political quagmire. “He had half of the people in the city wanting to tear the buildings down because they thought the residents were welfare queens living in high-rise palaces, and other half of the city wanting to tear the buildings down because they felt residents were incarcerated victims oppressed by a cruel government bureaucracy,” Michaeli said in a 2012 televised interview.11

The solution: Tear down the high- and mid-rises.

Demolition began erasing the city’s second skyline in the late 1990s, and the Plan for Transformation began.

The Overhaul

The plan rolled out before it had an official name. A first grader’s 1992 death became known as the shot that brought down the projects.12

Dantrell Davis held his mother’s hand one fall morning as she walked him to Jenner Elementary, a Cabrini-Green neighborhood school. From a vacant tenth-floor Cabrini apartment, a sniper fired at rival gang members but struck seven-year-old Dantrell. The little boy with apple cheeks was the third Cabrini resident from Jenner Elementary shot to death that year.

Outrage exploded internationally. The city’s establishment rallied around Dantrell’s murder, and conversations about overhauling public housing hit a fever pitch. Then–CHA chief executive Vincent Lane used the bully pulpit to advocate for a mix of poor, working and professional families at CHA properties. Lane had already flirted with promoting economic diversity in some South Side lakefront buildings.

Now, against a backdrop of tragedy, his idea gained traction and financing.

In 1994, the federal government awarded a $50 million HOPE VI grant to facilitate redevelopment of the Cabrini Extension North site, which included Dantrell’s building. The Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere program aimed to break up racial and economic segregation in public housing developments around the country. More federal money flowed to Chicago under President Bill Clinton after Daley received approval to expand this strategy of redevelopment, now formally known as the $1.5 billion Plan for Transformation, which officials submitted for HUD approval in 2000.

In CHA’s own words: “The guiding principle behind the Plan is the comprehensive integration of low-income families into the larger physical, social and economic fabric of the city.”13

The crux of the plan involved razing the high-rises for happily-ever-after mixed-income communities where a third of the apartments rented or sold at market rate, a third were affordable for working-class families and a third were public housing. No social science research informed CHA’s mix of housing. Officials argued that higher-income families could be good role models for poor families. CHA also wanted to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty; families shouldn’t feel that signing a lease to an apartment guaranteed they’d have it for life. Global powerhouse advertising firm Leo Burnett created a slick pro bono campaign called CHAnge to spread messaging among the public, philanthropists and civic leaders.

Most public housing residents refused to embrace the Plan for Transformation and argued that CHA spurned their input. They skeptically viewed the demolitions as land grabs and unequivocal gentrification designed to push them off of prime land. North Side Cabrini—minutes away from the city’s tony Gold Coast and in the shadow of the most affluent Chicago communities—tested the waters of CHA’s newfound direction. From 2000 to 2007, nearly $1 billion in residential property had been sold near Cabrini. Grocery stores and other amenities didn’t open in the neighborhood until monied white residents moved in. Although CHA buildings publicly had failed national standards, vocal residents accused the agency of purposely letting the high-rises decline so demolition became the only option. For example, in 1991–1992, Taylor had a 21 percent vacancy rate. In 1999, CHA owned 38,000 units and promised to demolish thousands of obsolete units so it could concentrate on rehabbing/redeveloping 25,000 units. That added up to a net loss of 13,000 apartments. The CHA believed there was no other option.14

The number of units is important because it determined how many leaseholders at the start of the Plan for Transformation had the “right to return.” CHA borrowed refugee-style language to describe lease-compliant residents who dwelled in a unit on October 1, 1999 and were thus eligible to move back into the refurbished homes. These residents were classified as 10/1/99 residents, and there were 16,846 10/1/99 families when the plan began.

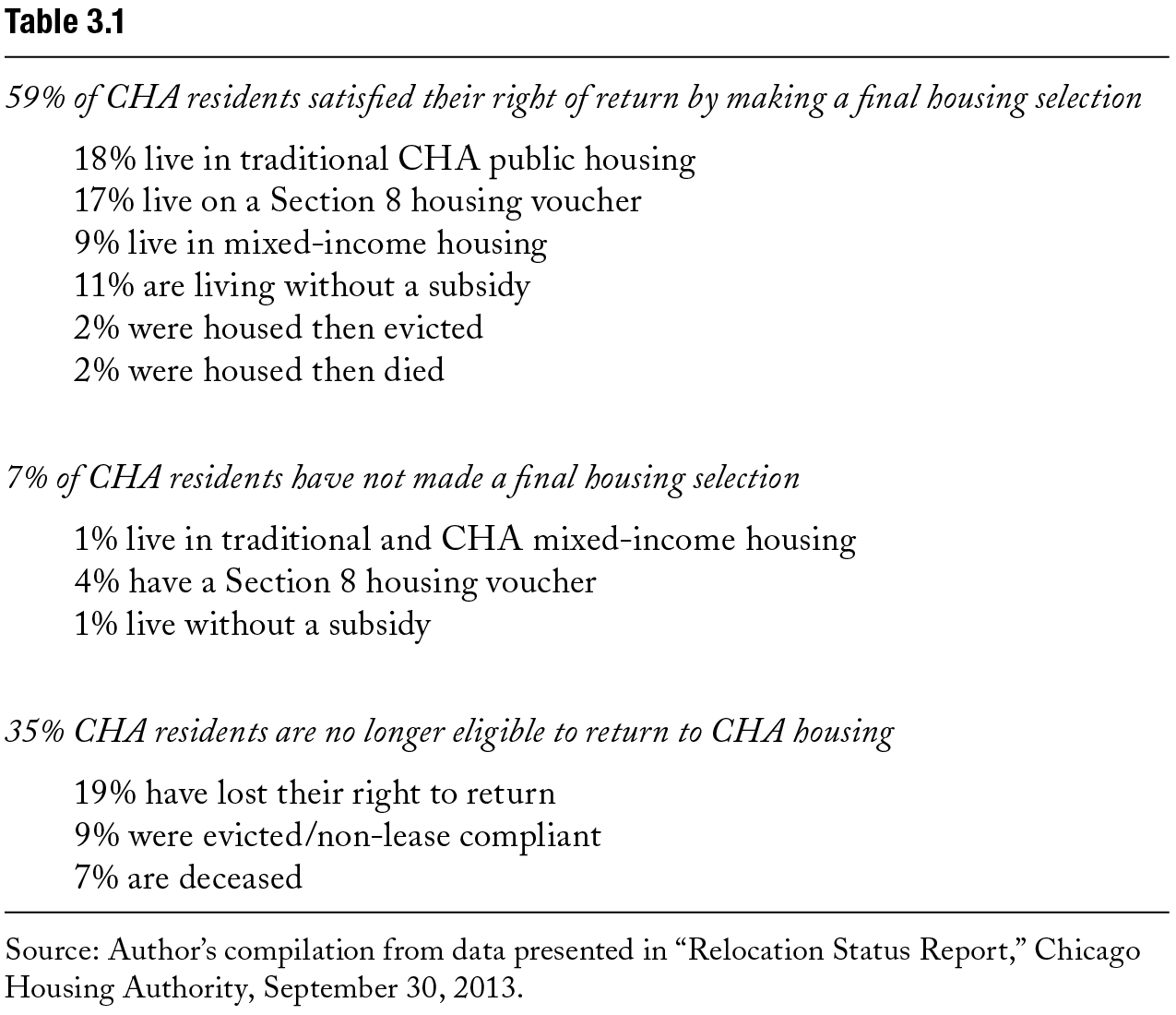

Originally, the Plan for Transformation had a 2010 date of completion. That date was extended to 2015. CHA missed that deadline too. Table 3.1 gives a snapshot of where those families are living—or not living—in 2013.

Based on CHA’s articulated mission of deconcentrating poverty and incorporating residents into the larger physical landscape of Chicago, the agency did not live up to its promises. Out of 16,000-plus families, only 1,468 permanently live in mixed-income communities with names like Legends (Taylor replacement), Oakwood Shores (Ida B. Wells replacement) and Park Boulevard (Stateway Gardens replacement).

* * *

Geographically, I didn’t grow up too far away from the Robert Taylor Homes, but the mental gulf stretched far beyond those miles. I observed the cinder-block wall along the Dan Ryan Expressway, those anonymous ashen towers occupied by people locked out of society. My segregated world never intersected with that hypersegregated island. By the time I enrolled in graduate school at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in 1998, I used the beat of urban affairs in one of my classes to explore public housing within the beginning of the Cabrini teardowns. When I moved back to Chicago in 2006 to be an urban affairs reporter, I observed the rapid dismantlement of traditional public housing.

The Chicago Reporter, a local investigative magazine on race and poverty, assigned me a cover story on the history of the Robert Taylor Homes months before the 2007 demolition of the very last tower. I set up an interview with one of the last handful of families at the building. Initially my middle-class assumptions guided me. As I walked toward the infamous project, the ugly, faded-beige building begged to be torn down. Graffiti-strewn hallways led to a rickety elevator. I just knew the people longed to exit the dank place and move to greener pastures.

Sixty-five-year-old Barbara Moore (no relation) disabused me of that perception. She moved to Taylor in 1967 from one of those despicable Black Belt kitchenettes with her two young sons, basking in her beautiful apartment equipped with new appliances. Moore said as the years passed, management ignored work orders and the buildings fell into disrepair while she bounced from one low-wage job to the next.

She fully understood how society viewed her and her neighbors.

“Women have been degraded,” she told me. “It seems as if people on the outside believe all of us are whores, bitches, dropouts, have babies. Like we smell, don’t take baths.”15

Moore’s observations about how society views public housing residents are spot on. Implicit in her statement is that she’s seen as nothing more than a Reagan-era welfare queen gaming the government in her high-rise ghetto palace. A recurring theme I’ve witnessed in my reporting of low-income communities is this: People don’t like poor people. They don’t deserve public assistance. They don’t deserve our sympathy.

Despite the dilapidation of Taylor, Moore clung to the cliché there’s no place like home. The ache of home knows no income or class limitations. I walked into that interview thinking that Taylor residents surely wanted to leave. I walked out curbing my own biases to appreciate that the cliché of home is real. I thought about how it would feel if an outsider unsentimentally ordered me and my family out of our home. No one wants to be told that where they live is fucked up. Home isn’t where the hatred is. For public housing residents, bouts of pain or institutional neglect may have colored their experience. But so many of them wanted to return home, to their new-and-improved address.

Over the course of the Plan for Transformation, CHA residents fought and sued to stay. Sometimes they achieved victories. Federal judges ruled that a detailed plan for residents had to be in place before CHA demolished buildings at Cabrini and Henry Horner. On the South Side, less litigious Taylor and Stateway Gardens residents moved out more quickly because of an aggressive demolition schedule; therefore, more empty tracts of land dotted the corridor.

Public housing residents have floundered under this massive plan. Those thrust into the private housing market struggled with new bills for heat and electricity, which previously were covered by public housing. Children shuffled from school to school during multiple moves. Between 1999 and 2015, CHA had eight different chief executives. Even CHA admits it underestimated the breadth of executing the now billion-dollar Plan for Transformation. Although leaders may have wanted families to go forth and thrive in a brave new Chicago world, that wasn’t easy. The resident population included people with substance abuse problems, spotty work histories and little education. CHA housing is often the housing of last resort for such families.

But some residents have literally been left behind. CHA couldn’t keep up with all of the 10/1/99 residents and hired a private firm in 2008 to the tune of $900,000 in a quest to track down residents.16

CHA could not have predicted one of the biggest blows to the Plan for Transformation: the housing crash of 2008, which slowed down the pace of private developers building the mixed-income communities. Market-rate housing sales slumped, and private foundations invested in CHA’s success offered down payment assistance to jump-start home buying. A number of for-sale units switched to rentals.

Resistance among public housing residents sometimes boiled down to a reluctance to change. Mothers in Taylor had learned how to survive. Families relied on each other. Neighbors built close communities in tough circumstances. A lack of a formal economy produced a thriving underground economy through the bartering of food, services or child care. To this day Facebook groups wax nostalgic on what it was like to live in those fallen buildings. (“Remember Mrs. Walks who ran the laundromat?” “When you on punishment and your friends live one floor up or down on the same side as you and you still get to talk to them hanging out the window!!” “Mrs. Mattie King baking everything . . . her cupcakes were better than hostess lol I loved that lady & so did my mom.”) Former residents post family pictures and use the social media site as a bulletin board to find friends. YouTube videos lament Taylor’s demise with grainy footage of demolitions. I’ve heard over and over again people say they wept when the moving vans pulled up. Many people who lived in high-rises didn’t consider them an inner-city prison. Life was more than a ghetto.

In one conversation, Alaine Jefferson, 40, told me half a dozen times that she wished CHA would rebuild Stateway Gardens the way it was. “There was a lot of love in Stateway,” Jefferson said. “You know how they say it takes a village to raise a child? Stateway was that village.”17

The young mother raised her three school-age children in Stateway from 1993 to 1999 and shared memories with me. If her daughter got in trouble, Jefferson said neighbors flooded her with phone calls. Jefferson volunteered at the local park district and coached the Stateway girls in jump rope competitions. Her children took gymnastics and hockey and did art projects that turned juice boxes into checker pieces. In the summer, Jefferson helped monitor a free summer breakfast and lunch program for youths. One day every week, neighbors collectively cleaned their gallery-style porches. On hot days, Jefferson and friends sat under the building in the breezeways to cool off.

“My favorite time was just the togetherness of the building,” Jefferson said. She attended early Plan for Transformation meetings and said no one ever asked residents what they wanted. When I asked if she wanted to live in Park Boulevard, the mixed-income development that replaced Stateway, Jefferson shook her head no. “It looks terrible. You have a lot of empty space.”

To some critics, the Plan for Transformation is sarcastically judged a success if the standard is based on demolition. The State Street corridor is more bare than settled. Miles of vacant land make it look like an urban prairie. In fact, in 2012 CHA said it controlled 400 acres, an area bigger than Chicago’s downtown showpiece Grant Park.

Subsidized Housing in the Private Market

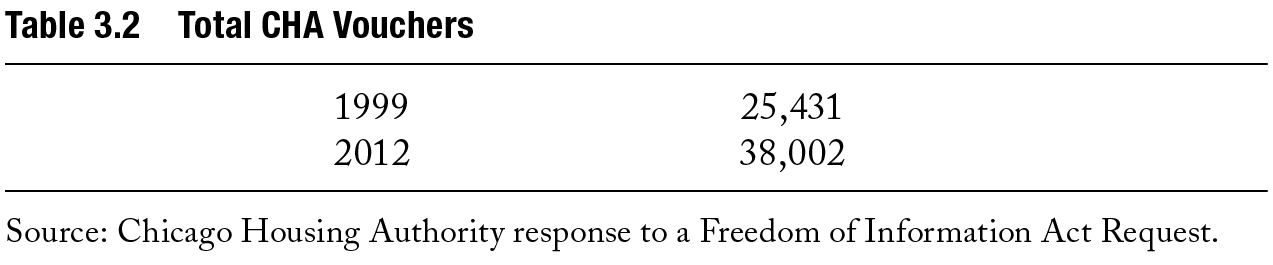

Most 10/1/99 residents rent in the private market with a Housing Choice Voucher, the program that replaced Section 8. This move dovetails with a national trend of more voucher management by public housing authorities. Underscoring the need for affordable housing in the city is the fact that CHA has a ridiculously long wait list of tens of thousands of people.

MIT professor Lawrence J. Vale writes in Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities: “Of even greater concern, in comparison to others in the CHA system, those who relocated with vouchers between 1999 and 2008 exhibited stagnating employment rates, lower earnings, higher rates of need for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and food stamps, marking them as more vulnerable than those who remained in conventional public housing or moved to mixed-income communities.”18

In March 2005, CHA settled a class-action lawsuit in which CHA relocates claimed they had been resegregated in the private market with vouchers in violation of fair housing laws. The agency modified its programs to encourage former CHA residents to move to economically and racially integrated communities. Families received access to social services. The public housing agency implemented a resident service program in 2007 to address the trauma of poverty. The Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank, found that residents who received wraparound services and intensive case management had increased family stability.

CHA likes to boast that vouchered-out public housing residents are not the majority in any of Chicago’s 77 community areas. Of course not. That would be impossible in a city of almost 3 million. But numbers reveal that the largest cluster of voucher holders live in segregated black neighborhoods. Those neighborhoods have a good number of residents living below the poverty level and have 1,000 or more voucher holders living within their borders.19 Meanwhile, the whitest, and some of the most affluent, neighborhoods in the city have the fewest number of voucher holders.

Kimberley McAfee, 42, is satisfied with her Woodlawn duplex, for which she currently uses a voucher. A Chicago Public Schools lunchroom attendant and mother of five, McAfee grew up in Stateway Gardens and got her own apartment when she turned 18. In 2001, at the beginning of the Plan for Transformation, she reluctantly left. Over the years, she’s had a long journey with multiple moves.

The first was to South Shore, a black lakefront neighborhood where pockets of affluence abut poor, multi-unit apartment buildings. South Shore is home to the largest number of voucher holders in Chicago.

“We was trapped in four different kinds of gangs,” McAfee recalled. “[The apartment] balcony was kind of weak and the kids couldn’t play on it. They were playing out front and we heard gunshots. Two of my daughters hid under a car.” The girls were 10 and 11 years old. Fortunately, no one was hurt during the daytime shooting.20

After a year, the family moved to Englewood. “That block was kind of decent,” McAfee told me. “No, let me take that back.” She recalled that a group of young boys shot at her neighbor. No one was hurt. She lived there for two years. “The reason I moved from there was the apartment was in foreclosure in 2003. The landlord had told us we had to move because he couldn’t take care of the building.”

Move number three led the family to a house in Roseland on the South Side.

“It was all right,” McAfee said. “My girls kept getting into it with the grown people on the block because the boyfriends of grown people were trying to holler at my daughters who were in high school.” They lived there two years. The bathroom ceiling caved in, and the house went into foreclosure.

Then the family moved back to Englewood, which didn’t work out either.

“They just stayed in shoot-outs over there. Some boy got shot with an Uzi in front of our house. I didn’t know him. My kids were there.” After two years, the family left and moved to the Woodlawn duplex in 2010.

Unsurprisingly, McAfee loved Stateway. I asked her about the difference between the violence there and the violence she’d experienced in the voucher world.

“I was more protected in the projects than anywhere else out here,” she explained. “When they [the Gangster Disciples gang] were at war, they let everyone know so all your kids would be in the house. I always felt safe in Stateway.”

McAfee brushed off violence as if it were lint on her pants. In a cruel twist, she got shot in the leg in 2007 while attending a Robert Taylor Homes reunion on State Street, in an empty field a mile south from the former development. “I was an innocent bystander,” she said. The bullet is still lodged in her buttocks, and there’s a rod in her leg. During that shooting, a boy was killed.

When the Plan for Transformation was in draft form, resident activists from the Coalition to Protect Public Housing predicted voucher mayhem. “The coalition also thought that the plan’s reliance on having public housing residents take Section 8 vouchers to find housing in the private rental market was unrealistic. The criticism was based on the regional rental market study’s documentation of the tight rental market. Consequently, many relocated CHA families were using the vouchers to move to areas that were as segregated as the CHA communities they were leaving,” writes Patricia A. Wright in a chapter in Where Are Poor People to Live? Transforming Public Housing Communities.21

CHA is not solely responsible for families’ individual housing choices. Families with vouchers seek welcoming areas or ones near their social/familial/job networks. Landlords discriminate against voucher holders. HUD says it wants families to live in better neighborhoods, but what the federal government is willing to pay is, by and large, insufficient for market rental rates in low-poverty areas. Finding a two-bedroom apartment for $800 in, say, the North Side’s yuppie Lincoln Park area is virtually impossible. CHA did experiment with “super vouchers,” putting people in apartments where rents can start at $2,300, but political pressure quashed that policy.

Meanwhile, several other black South Side neighborhoods have absorbed more than 1,000 voucher holders each. These are not poor communities, but 20 percent or more of the population lives in poverty. Homeowners make up Chatham, Greater Grand Crossing and Auburn Gresham, but the proximity of these areas to lower-income black neighborhoods renders them vulnerable to outside forces, such as crime. These black middle-class and working-class areas thrive with strong block clubs and efficacy, but they also teeter and could use more city and private resources. Certainly, the dispersal of public housing families rocked these communities, and the timing of the Plan for Transformation inflamed instability. Every single community that received a large number of voucher holders declined in tangible ways between the 2000 and 2010 census. Median household incomes and home sales plummeted. Poverty markedly increased. Whenever spikes in crime occur on the South Side, mutters about the “project people” can be heard. There’s a nugget of truth in those complaints.

The drug trade has relocated, and the criminal spillover has distressed Chatham and Auburn Gresham. Open-air drug markets prospered at public housing developments, but it’s important to note that drug dealers weren’t necessarily CHA residents. Dealers plied their trade in a vibrant criminal setting at neglected high-rises. If an open-air drug market collapses because of closed buildings, displaced dealers relocate in new areas, and turf wars break out. Freelance drug crews seek corners to continue their illegal enterprises. A police commander in Auburn Gresham told me in 2009 that half of the drug dealer offenders arrested in his district had arrest histories around public housing.22

CHA persistently and rightfully defends the majority of its residents as law-abiding citizens. To shed light on the impact of relocations on neighborhood crime, the Urban Institute released a study in 2012. Researchers found that crime was worse from 2000 to 2008 in neighborhoods where former CHA residents used vouchers. Violent crime was 21 percent higher in neighborhoods with high concentrations of voucher holders than in neighborhoods with no relocated households. Violent crime dropped about 26 percent across the city during this same time period. According to the Urban Institute, areas inhabited by voucher holders experienced less of a decrease of crime than occurred in areas without clusters of voucher holders.23

Relocation might affect crime for three reasons: a disruption in social networks, which puts residents at risk of committing crimes or becoming victims; new residents disrupting the communities’ sense of mutual trust and social cohesion; or residents and their associates engaging in criminal or drug activity when they lived in public housing and bringing similar activity when they relocated.

However, stereotypes allow voucher holders to be scapegoated and stigmatized. Just about anything that goes wrong in black Chicago neighborhoods gets blamed on “those people from the projects tearing up our neighborhoods.” Intracultural conflict is real but can be less about violent crime and more about quality of life. Former high-rise residents occupied public space at their developments because there was no backyard to fire up a grill, no back porch to set out lawn chairs, no patio for entertaining. When voucher holders move to a neat block with bungalows and two-flat apartment buildings, putting a weight bench on front lawns, selling potato chips on corners, playing cards on the street or barbecuing on the sidewalk fails to endear them to neighbors.

“They had to get educated to us and we had to get educated to them,” Keith Tate, president of the Chatham Avalon Park Community Council, told me. Tate said that, over the years, Section 8 administrators from CHA have come to community meetings at the request of homeowners. “Initially, we said we will embrace people coming from Section 8 but we need them to understand we have a community with standards and values.”24

When problems surfaced on blocks, homeowners checked to see if problem renters had vouchers.

“Unfortunately, [CHA] would saturate a particular block by bringing in a number of voucher individuals, and they all knew each other. One block we had seven houses that were all identified [as being rented to voucher holders] and they all destroyed the block. We got all of them moved. That connectivity gave them control of the block. When you have that kind of scenario, it becomes chaotic,” Tate explained.

In response to the chaos, neighbors formed phone trees to let an absentee Section 8 landlord know of trouble brewing. One home housed four mothers with 12 children among them. “It was off the chain,” Tate said. “Every weekend a party. Kids were everywhere. We had to bring it to the owner of the house, and he was like it couldn’t be a problem. Every time there was a problem, we called. We didn’t care if it was one, two, three a.m.” Eventually the landlord tired of the barrage of calls from multiple neighbors and got new tenants.

At a monthly Chatham community meeting in 2015, a CHA representative answered questions from residents and ended up busting assumptions. He told the homeowners that if they suspected a troubled property was Section 8, they should call CHA. In his experience, 70 percent of complaints do not pertain to Section 8 properties. Within the communities, however, bad behavior, criminality, prostitution, barbecuing on front lawns and pit bulls fighting are what people associate with Section 8.

The Urban Institute’s Sue Popkin has studied CHA for more than two decades. She says that, for the most part, people are living in better housing in safer neighborhoods. But she notes that relocation has been extremely hard on children and CHA hasn’t given them enough support. Youths struggle academically and exhibit the effects of growing up around violence. “I worry a lot about the kids,” Popkin once told me. “The services that helped the adults do better don’t seem to have helped the kids. It’s an urgent issue. These are kids who have grown up in families who’ve lived in chronic disadvantage for generations, and it’s going to take more than just moving to slightly safer places to help them on a better trajectory.”25 Other research shows that public housing residents say their stress level is down since moving into mixed-income neighborhoods.26 Larger structural issues in Chicago around employment, discrimination and access to opportunity must be addressed in tandem with putting families on a path to self-sufficiency.

The lives of many CHA residents did improve. Although Alaine Jefferson missed her tight-knit Stateway community terribly, she was climbing the economic mobility ladder. When I interviewed Jefferson, she was a Chicago Public Schools part-time bus aide while she worked on a master’s degree in accounting at Robert Morris University. In 2013, she earned a degree in human services from the University of Phoenix. Jefferson told me that Stateway was a stepping-stone. “I didn’t have direction. I was all over the place. I didn’t know what I wanted to do [at] that time. I knew I wanted to graduate from college and get a good job. I gained a lot of experience in Stateway with the park district,” she said. “If I hadn’t gone through Stateway, I wouldn’t be as strong as I am today. I’ve been encouraged and been blessed.”27

At the time of our interview, Jefferson used a voucher to live in a rehabbed apartment in Washington Park on the South Side and was taking advantage of CHA self-sufficiency programs, where she was learning financial literacy and job-interviewing skills. Next, Jefferson wanted to go through the home ownership program at CHA.

“I don’t want to pay rent; I want to pay a mortgage. I’m building up money to be financially stable. I couldn’t pay for a furnace if it went out. That’s my reason for staying in the voucher program at this time.” Jefferson’s goal was to move to the western suburbs, where there are an abundance of jobs and more resources, opportunities and amenities.

Those who live in mixed-income apartments experience less crime and less stress in prettier surroundings. But just 9 percent of 10/1/99 families are afforded that opportunity. To qualify, residents go through a rigorous background check, counseling, rules orientation, social services assessment and training before they move in. Not everyone qualifies to get to or makes it beyond that point. Housing counselors bark like drill sergeants when they lecture on social behavior, such as how often to dust and do chores.

Race and class flare-ups pose complications at these properties. Condo owners have blamed building wrongdoings on CHA residents only to find out a fellow owner put the trash in the wrong place. All mixed-income renters—CHA, affordable and market rate—are required to take yearly drug tests.

Cultural clashes run the gamut.

Cabrini public housing residents have told stories about holding a postfuneral repast (reception) in an apartment. White homeowners who now live on the former Cabrini footprint called the police, not knowing this is a common black ritual. One public housing renter received an eviction notice when an annual inspection turned up a cluttered closet. Lawyers intervened and the woman got to stay.

Westhaven Park Tower is a building with mostly white condo owners and black CHA renters on the footprint of the former Henry Horner Homes. Owners wanted CHA to provide 24-hour security to prevent their public housing neighbors from having unwanted guests. They complained about late-night noise and that thorny issue of loitering in the lobby, going so far as to remove standard apartment building lobby furniture, which later was put back.

In demonizing the so-called undeserving poor, mixed-income homeowners forget that they too benefit from subsidized housing. The new communities are built on federal land, which CHA received for free and allowed developers to construct properties and sell units more cheaply than if they had to purchase the land. One Westhaven resident said he expected “everybody to live in the building like I live in the building.”28

These incidents touching on the cultural polarity in mixed-income developments are simply how people live. Upper-middle-class condo owners enjoy socializing in their units. Public housing residents see benefit in communal living that’s more indicative of true city dwelling. One person’s loitering is another’s hanging out.

* * *

Accusations of purposeful segregation are nothing new to CHA.

In 1966, black residents accused CHA of violating their rights by building public housing exclusively in black neighborhoods and creating racial quotas to limit the number of black families in white public housing when there were white developments. In 1969, in the landmark Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority case, a federal judge found that CHA had deliberately engaged in discriminatory housing practices.29 One of the many outcomes was that new public housing was to be located in nonblack neighborhoods. It was a very slow process to build, for example, three units (hence, scattered-site housing) in white census tracts. The other major initiative was to use the Section 8 program to place 7,100 families in predominantly white suburbs. The results were mostly positive for the families.

Today it is impossible to desegregate family CHA public housing because the overwhelming number of CHA residents and applicants are black. The federal court can’t order minority families to white public housing sites because there are none. Due to high costs and political opposition, CHA no longer builds scattered-site housing, though it could be a solution. Faced with those problems, CHA relied on vouchers and the mixed-income model when the Plan for Transformation began.

I don’t regret that the city knocked down the public housing high-rises. Nor am I unsympathetic to the fervent pull of home residents continue to feel. Love, family and community flourished at public housing dwellings despite the realities of crime, disorder and disinvestment.

But the disappearance of those structures from the city’s skyline has also erased the visibility of public housing families in Chicago, and the Plan for Transformation’s public policy has benefited and also failed thousands of families.

CHA’s Plan for Transformation is woefully behind schedule due to broken promises, a housing collapse and bureaucratic paralysis. CHA has been operating outside the sphere of real political accountability to speed things along or rethink how to house residents. The use of subsidized housing vouchers in the segregated private market has failed the expressed plan of breaking of concentrated poverty.

When I learned about a small program dubbed “super vouchers,” I thought CHA had figured out a way to reverse the Section 8 paradigm of putting families in neighborhoods with high segregation and poverty. The mobility program allowed families to live in areas with fewer than 20 percent in poverty and low subsidized housing saturation. CHA spends extra federal money to make up the difference in higher rents in those areas. Only 10 percent of the voucher holders were in this program.

In 2014, I interviewed a black working woman who lived downtown on a super voucher, which allowed her to receive up to 300 percent of fair market rent. She wanted better schools for her two children. Finding an apartment wasn’t easy; at first she faced discrimination from landlords who didn’t want to take her voucher. She filed a complaint against the city.

As word spread about super vouchers, criticism heated. Landlords hated the federal program. The public didn’t understand why even just a few low-income people got the chance to live in some of the most exclusive buildings in the city at taxpayer expense. Then Aaron Schock, a white Republican congressman from a small Illinois town who later resigned from his seat as a result of other controversies, stepped in with outrage. And poof, CHA altered the program to exclude luxury high-rises, a change that was perfectly legal. CHA changed the policy from 300 percent to 150 percent of fair market rent; 260 families were affected, a mere fraction of the tens of thousands of people on vouchers.

I was stunned by CHA’s swift policy change. This was one of the rare times when a politician exerted pressure on CHA, and officials jumped like circus animals. Although this congressman had no ties to Chicago or CHA, the agency acquiesced anyway.

Clearly, race and stereotypes about voucher holders informed the public outcry. Most of the people in the opportunity areas didn’t live in a building with a doorman. Yet the public didn’t think the few families that had been moved to such buildings belonged in any luxury high-rise in Chicago. They didn’t deserve a “high-rise palace” that didn’t mirror something like the Robert Taylor Homes. They didn’t belong in a place that wasn’t a segregated black ghetto.

This incident recalls Barbara Moore, one of the last Taylor residents, and her observations about poor black women being degraded for living in public housing. A simplistic notion often guides us: Society doesn’t like poor people.