“Do you know what segregation is?”

“Yes—separation.”

—All-black Mollison eighth-grade boys’ class discussion after reading “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King Jr.

My foray into integrated education was launched out of pure convenience.

Neither our Chatham neighborhood nor surrounding black areas had all-day public school kindergarten, according to my parents. Only half day.

“That was a real issue for me and your mother,” my father recalled. For dual-working parents, the Chicago public school two blocks away was not an option.

The year was 1981. My parents heard about a new magnet-style program at a public school in the South Side Beverly neighborhood, a fledgling integrated community that didn’t succumb to white flight.

A yellow school bus ferried me and a load of black children—all from South Side black working- and middle-class neighborhoods—to Sutherland Elementary, a beautiful redbrick colonial-style school with double-hung, oversize bay windows. It took us about an hour to get to school each day.

“At the time, they had the ‘deseg’ program in the city of Chicago, and a lot of black families looked at it as an opportunity to go to diverse schools outside of their neighborhood,” my mother recalled.1 Sutherland students scored high in reading and math.

I attended Sutherland as a result of a last-ditch integration effort by Chicago Public Schools (CPS). Decades of other so-called reforms never achieved true integration, culminating in white students fleeing CPS beginning in the 1960s.

In 1980, the U.S. Justice Department filed a lawsuit against the Chicago Board of Education, alleging a dual school system that segregated students on the basis of race and ethnic origin was in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Back then the percentage of white students in the district was 18.6. The decree required CPS to implement a voluntary desegregation plan to create as many racially integrated schools as possible.

The consent decree is what helped allow my voluntary transfer to Sutherland.

“I loved the teachers there,” said my mother, a retired special education teacher and administrator in CPS. “You had an excellent education. I couldn’t really ask for too much more than what you had.”

My voluntary busing experience belies what’s burned in popular imagination. This wasn’t 1974 Boston. No screaming white parents hurled epithets at black students as we rolled up to the school in a yellow school bus. White students didn’t taunt us on the school steps. Law enforcement didn’t arrive at the scene to escort us into the building. A decade earlier, white parents resisted integration in CPS, but by 1981, the percentage of whites in the district had dropped precipitously. Meanwhile the Beverly neighborhood was grappling with nascent integration, and white resident leaders promoted integration as an asset.

When they got old enough for school, my brother and sister joined me on the bus.

“All of you seemed very happy there,” my mother said. “Teachers cared about you and they were very easy to talk to if there were any problems, and the administration was great.”

I recognized differences, although it didn’t register until college that I had participated in something weighty called “desegregated busing.” Growing up, my father delivered the typical black parent lecture about being “twice as good” as white peers, but he never prepped us about our role in helping integrate a school. Our parents didn’t treat us like pioneers or mini Ruby Bridges.

Normalcy ruled our school lives. White friends invited me over for sleepovers. Black and white students mimicked Star Wars on the playground with imaginary light sabers. Love and disdain for certain teachers transcended racial lines. We all agreed the Polish gym teacher sucked. But I observed many white students walking home for lunch. Bused black kids lived too far for that. And our moms worked. White stay-at-home moms dropped in for Friday pizza days and volunteered at PTA book fairs. On a more childlike wonderment note, my seven-year-old self observed that black kids ate wheat bread and white kids ate white bread during lunch. Imagine my surprise when a white classmate unpacked a wheat sandwich. The only racial incident I recall involved a white nemesis who snickered that she didn’t know black people could afford to go to Disney World after I told her about a family vacation. I likely rolled my nine-year-old eyes at her; white and black girls alike found her as affable as a Garbage Pail Kid.

I loved Sutherland. We adored our avuncular white principal, Mr. Frantz, who occasionally stopped by our house for family barbecues. He also would pop into my classroom to scope my lunchbox. He knew my mother packed me leftover dinner since I disliked sandwiches without bacon. Once he lucked out and scored a bite of lobster.

Black and white teachers helped mold me. Ms. Traback introduced me to I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in sixth grade. Ms. Becic fostered a love for language arts. Ms. Turner treated us like her children. I loved school and reflect positively on Sutherland without racial scars. Sutherland complemented my black Chatham life.

Yet in first grade, my parents transferred me out of Sutherland for Beasley, a high-performing, mostly black elementary school that required an admissions test across the street from the Robert Taylor Homes public housing development, because the school earned the reputation as one of the 1980s it Chicago schools. Beasley schooled a bevy of black middle-class youth from outside the neighborhood. After a month, I transferred back to Sutherland.

When people asked why I returned, I parroted my dad without fully understanding what he meant. “My father says he wants me to have an integrated education.”

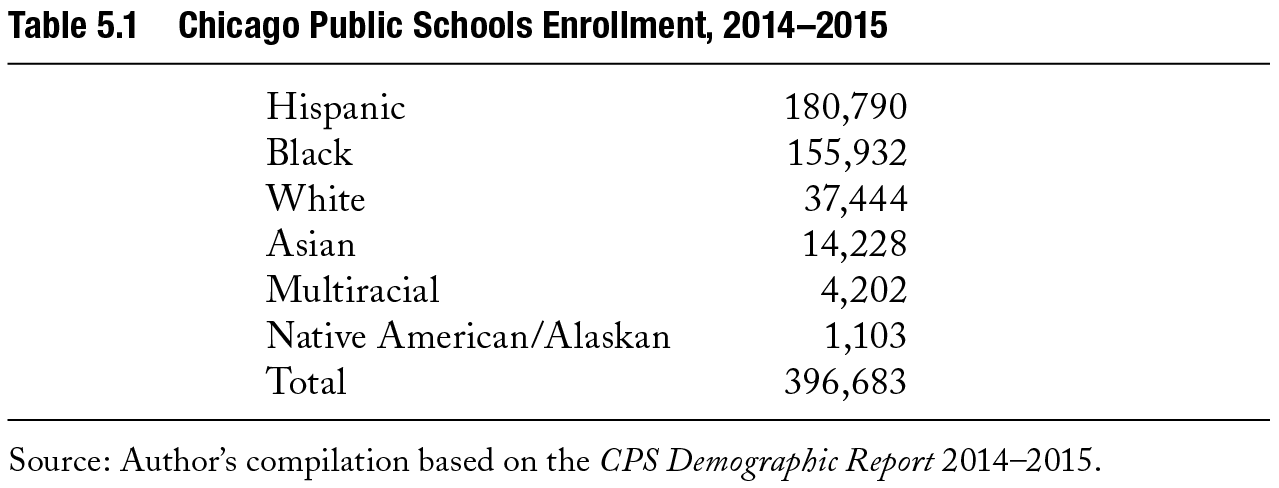

Today, no one talks about integration in CPS. In school reform debates, the topic isn’t in vogue. Integration has been replaced by charter schools and yearly standardized testing as the nation’s go-to strategies for improving education for black children. Soon I realized: Why would anyone talk about integration? Over the course of 50 years, the white population in CPS dropped from 50 percent in the early 1960s to 9 percent in 2014.

While city demographic changes occur in many neighborhoods, Chicago remains diverse. White people live here but don’t send their children to public schools.

“In terms of dealing with overall patterns of segregation in Chicago, it was pretty much an abject failure. In terms of creating a few interracial magnet schools, it was better than nothing. But it was never seriously developed to figure out what actually could be done,” Gary Orfield, a school desegregation expert and codirector of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California–Los Angeles, told me.2

Decades after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education and 35 years after Chicago’s consent decree that allowed me and my siblings to attend Sutherland, the city’s children still don’t go to public school together. Why did Chicago fail to integrate public schools?

In short, the answer is court failure and lack of political will. Scared white families left the city and/or district. White people didn’t want to give up their privilege or segregated education for blacks. On the federal level, changes in presidential administrations hurt CPS because priorities had changed. Historical and legal wrangling over public education foiled any chance of remarkable change. Now black leaders and organizations don’t take up integration as a goal.

But after Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled separate public schools for black and white students as unconstitutional, Chicago seemed poised to change. The landmark 1954 decision strengthened Chicago black parents’ resolve toward ending segregation, but the case meant little on the ground. Civil rights laws prohibiting discrimination served school districts in the South but fell victim to Chicago’s powerful and well-oiled political machine. Mayor Richard J. Daley resisted desegregation up until his death in 1976.

“Most places were forced to change by some degree of civil rights enforcement, but Chicago was able to exercise enough political power to protect its singularity,” Orfield explained.

In “Desegregating Chicago’s Public Schools: Policy Implementation, Politics, and Protest, 1965–1985,” Dionne Danns writes that the city is distinctive when compared to other major cities because no major court ruling came from Chicago. In other northern cities, federal and Supreme Court rulings were the sources of desegregation policy. Chicago policy came directly from the federal and state governments.3

CPS squandered the opportunity in the 1960s and 1970s when a substantial number of white students attended public schools by routinely ignoring desegregation mandates without suffering financial repercussions. Danns writes that as federal and state officials pursued desegregation, Chicago school officials “dragged their feet and continually issued voluntary plans calculated to stymie rather than promote desegregation.”4 The result over five decades has been fewer white students and increased clustering of those students in fewer and fewer schools. But with integration out of the limelight, even limited gains are beginning to disappear, and the word “resegregation” has become part of the conversation.

But not in the suburbs.

Surprisingly, from 1990 to 2010, white students in suburban Chicago attended more diverse schools. However, in Chicago, the number of highly segregated black and Latino schools jumped. The number of Chicago public schools 90 percent or more black increased from 276 to 287 while the number of racially isolated Hispanic schools increased from 26 to 84. Meanwhile, the number of integrated schools—where no one race comprises more than 50 percent of the student body—plummeted from 106 to 66.5

On the surface, the city’s demographics don’t suggest those figures. Chicago is not exclusively black and/or Latino because, unlike many other midwestern cities, Chicago has maintained a white population. The city is almost equal parts black, Latino and white. But while roughly a third of Chicago’s total population is white, there aren’t that many white school-age children living in the city. Here is CPS student racial data that I received from the district.

In 2012, there were 65,259 white children living in the city of Chicago, grades K–12.6 Even if all of them enrolled in CPS, they’d still be far outnumbered by students who are black and brown. Many whites treat the city of Chicago as a revolving door. They bolt, presumably to the suburbs, once they have school-age families. They are replaced with single or childless whites, and the cycle resumes.

Despite the bleak numbers, experts say the city can find creative, innovative ways to curb the number of racially isolated schools in poor black and brown communities. Integrating schools isn’t about getting black and white children to sit next to each other just for the sake of kumbaya harmony. Diversity is worthy, and segregation needs to be broken up because it perpetuates a system of inequity. Black children don’t need their desks to be next to white children because whites are better. Integration is about the proximity of power and resources. Chicago lost potential and lost the chance to understand what the real benefits have been.

But integration could be regained.

* * *

During the month of January 1962, black parents and students staged a sit-in at Burnside Elementary in the West Chesterfield neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. As the community transitioned from white to black, the public school suffered from overcrowding. Children attended school on double shifts to accommodate overflowing classrooms. Some students started at 7:45 a.m.; others arrived at 9 a.m. Some students left early afternoon; some stayed late. Some classroom instruction took place in the teacher’s lounge and the school auditorium.

Parents had a solution: They demanded that some seventh- and eighth-grade children transfer to nearby Perry Elementary. But rather than integrate that school, the Chicago Board of Education ordered the upper graders farther away to black Gillespie Elementary.

“But we didn’t go, which is why we had the sit-in,” recalled Tony Burroughs, one of the eighth-grade protesters in 1962. “Perry was closer and the black kids that lived closer to Perry school were not allowed to go to Perry. So our parents’ stance was—if you integrate Perry, then those students that live closer to Perry would go, which would relieve the overcrowding in Burnside. We would still only have to walk three or four blocks to school, instead of 16, 17 blocks.”7

His mother, Mary Burroughs, Burnside PTA president, led the demonstration.

“My mom wasn’t really a civil rights worker, but she was very active in the community. She explained everything to us every day. Why we were having the sit-in, what would happen when we’d go every day. Why we were going, this whole thing about racism,” Burroughs told me.

The Burroughs family had moved to the Burnside neighborhood in the late 1950s after neighborhoods outside of the Black Belt opened up to blacks. Tony Burroughs understood that segregation didn’t uplift the race because a childhood accident had taught him society viewed him as a second-class citizen.

Ten-year-old Burroughs slid on a piece of glass while playing baseball with his brother in the alley. His parents took him to a hospital two blocks away.

“The hospital said, ‘We don’t serve niggers.’ So we had to leave,” Burroughs remembered.

The family drove to another hospital.

“We walked into the emergency room there and they wrapped gauze around my hand three times and said, ‘We don’t serve niggers.’”

A third hospital finally accepted him.

“I was in emergency surgery for three hours. The tetanus had crawled up my arm and the physician had to make this incision and bring the attendants to tie my arm up. My mom explained why, since I was a black person, I couldn’t get service at these hospitals. So I knew what racism was about. Or at least I knew something about what it was about. So when my parents explained what was going on [at Burnside], it wasn’t anything foreign to me.”

Young Tony grasped the concept of racism, and the hospital incident solidified the importance of the Burnside protest. As the sit-in pressed on, the white principal removed the chairs and relocated protesters from the hallway to the basement. Officials threatened students with truancy. Police arrested mothers, including Mary Burroughs. She was fingerprinted, and Jet magazine captured the image.

Burnside parents filed a class-action lawsuit—in Tony Burroughs’s name—against the Chicago Board of Education. They asked for a restraining order to halt the transfer of students to Gillespie and $500,000 in damages.8

A judge dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that litigants had not pursued all state-level remedies against the defendant Board of Education before filing in federal court. Eventually the sit-in ended, and Tony Burroughs reluctantly transferred to Gillespie.

But the loss didn’t deter Chicago parents. They had been fighting before that case and would continue to fight for integration with invigorated activists all over the city. Fed-up parents took to the streets, City Hall, the courts and school grounds in the 1960s.

In 1961, parents of 160 black children requested transfers from overcrowded black schools to nearby white schools that had open classrooms.9 Request denied. That same year Webb v. the Chicago Board of Education alleged deliberate school segregation in violation of equal protection under the law. The U.S. Supreme Court found that plaintiffs didn’t exhaust the state’s administrative procedures before filing in federal court. In an out-of-court settlement, the Board of Education agreed to form a panel to analyze the school system “in particular regard to schools attended entirely or predominately by Negroes, define any problems that result therefrom and formulate and report to this Board as soon as may be conveniently possible a plan by which any education, psychological, and emotional problems or inequities in the school system that prevail may be best eliminated.”10 At the time, CPS was about 51 percent white.

Community groups refused to back down, and civil rights groups demonstrated. In Freedom Day boycotts, hundreds of thousands of students stayed out of school on various days during the 1963–1964 school year. Protests ratcheted up with a focus on Superintendent Benjamin Willis. Some compared Willis to Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace, who declared “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” and ordered state police to prevent integrated public schools from opening.

Willis presided over the district from 1953 to 1966—through the critical period of time nationally of Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He became one of the most controversial school figures in the nation for keeping black students in segregated, overcrowded schools, even though there were seats available in white schools.

The racist solution Willis applied to ease overcrowding was building mobile classroom units in front of black schools. Parents derided the units as “Willis Wagons.”

Willis resigned in 1963 when the Illinois State Court ordered him to implement a student transfer plan to bring a small number of black students to white Bogan High School. The board refused to accept his resignation.

My parents attended Chicago Public Schools during this time. For one academic year, my mother attended elementary school on a half-day schedule in Woodlawn because of overcrowding. At the time she didn’t grasp why. My father attended Burnside Elementary ahead of Tony Burroughs when whites still lived and attended school in the neighborhood. Fenger High School in Roseland was my father’s neighborhood high school. Because a new neighborhood high school in his newly black South Side neighborhood wasn’t built yet, he took the city bus to Fenger, where just a handful of blacks attended. Roseland was a few years off from full-fledged white flight. My dad hated Fenger. One day someone painted “nigger go home” on the school. He attended summer school so he could graduate early and escape prejudiced teachers. (Decades later, Fenger became a low-performing high school and made national news in 2009 when the beating death of Derrion Albert, a Fenger student walking home from school, was caught on camera.)

Meanwhile, the 1964 report tied to the Webb case—known as the Hauser Report—documented school segregation as a by-product of segregated housing patterns. “The intense dissatisfaction of Negroes with the prevalent pattern of de facto segregated public schools and with the quality of education in those schools in the City of Chicago must be understood as an expression of their rebellion against their general status in American society,” the report said.11 It noted that there were more Negro pupils than whites in classrooms and overcrowded facilities; Negro teachers with less education than white teachers; higher Negro dropout rates and lower test scores; and inferior Negro school facilities. Among the panel recommendations: changes in school boundaries to foster integration, faculty integration and free transportation for transfer programs.

True to form, the board did little with the report, and a coalition of civil rights, civic and religious groups grew tired of constant inaction. This trail of setbacks and frustrations show the deep-seated segregation permeating Chicago. It also helps us understand why the city continues to be so segregated. We’d have a much different public school system if the city had implemented recommendations in the early 1960s.

Black parents kept trying and kept losing, but they never gave up. In 1965, a coalition filed a formal complaint of discrimination with the U.S. Office of Education. It was the first major challenge to a northern school district under the newly passed Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its Title VI provision, which prohibited discrimination in programs that receive federal assistance. This covered education. Two years later, a report identified violations, and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) sought voluntary compliance.12 But because of blowback from Mayor Richard J. Daley and his powerful Democratic machine, the feds didn’t give Chicago a plan and trusted the Board of Education to do the right thing. HEW had planned to defer $32 million in federal funds for the city with the expectation that CPS would cooperate on desegregation, but Daley threatened that the Chicago congressional delegation and Senate GOP leader Everett Dirksen, of Illinois, would end support for all federal education. HEW backed down.

In 1966, Willis retired. His successor, James Redmond, unveiled a desegregation plan, which included limited busing of blacks to white schools. This prompted white parents to picket, and voluntary busing failed. Redmond’s plan also called for the creation of magnet schools. Blacks felt the plan wasn’t enough. Ultimately, the federal government never pressed for formal compliance. Redmond—joined by politicians and white residents—seemed more focused on appeasing whites who were leaving the city.

In 1971, the Illinois State Superintendent of Public Instruction filed binding rules mandating that no school may deviate more than 15 percent in its racial composition from the school district as a whole. Again, this was never implemented in CPS.

Then in 1973, the governor of Illinois signed a bill that prohibited mandatory busing as a remedy for school segregation. Time and again in the 1970s, the Chicago Board of Education was told to come up with a desegregation plan, but every plan was found to be faulty.

With President Jimmy Carter in office and Richard J. Daley gone, in the late 1970s the feds finally found some money to withhold.

According to a 1979 report by the Illinois Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights documenting Chicago’s failings:

The Chicago Public School officials often mention the impossibility of desegregating a school system with too few white pupils. They continue to attach responsibility for segregated schooling to residential patterns and housing preferences, occurring supposedly independent of government action. The Office for Civil Rights, HEW, has however documented . . . a long history of actions and/or omissions by the Chicago Board of Education over the years that contributed to or caused segregation.13

“There was never a doubt that Chicago was violating the Constitution, but every time you’d come up to do something serious, massive political power was used to protect segregation,” civil rights expert Gary Orfield explained.

In 1980, the U.S. Justice Department filed a lawsuit against the Chicago Board of Education, alleging a segregated dual school system.14 Allegations included drawing/altering attendance boundary areas that created segregation, segregated schools within segregating public housing and failure to relieve student overcrowding that maintained segregation. CPS implemented a transfer policy that allowed white students to avoid attending schools where they’d be the minority in favor of schools where they were the majority.

Creating magnet schools was a key piece of the decree. One rule those schools had to follow was that enrollment could be no more than 35 percent white. Eventually, this decree would fade into the abyss of empty desegregation plans when it ended two decades later.

* * *

On a snowy January morning in 2015, students trickle in with their backpacks before the 8:45 a.m. bell rings at Irvin C. Mollison Elementary. En route to homeroom, they swing by the lunchroom to pick up a free breakfast. Just about every student is eligible for free/reduced lunch.

Staff and teachers call out “good morning” to students in the hallway before ushering them along to homeroom. After slurping their milk, students stand for the Pledge of Allegiance and then recite Mollison’s creed—developed by staff with student input—about being black children ready to learn.

Mollison sits along a quiet stretch of Bronzeville greystones. The public school’s name comes from Irvin C. Mollison, the nation’s first black federal judge, appointed by President Harry Truman in 1945. The University of Chicago–trained lawyer was part of the team that represented Lorraine Hansberry’s family in the racially restrictive housing case of Hansberry v. Lee that was decided by the Supreme Court in 1940.

Mollison Elementary is familiar with the limelight, not because of its nod to black history but because of a contentious school policy. Chicago generated national furor when in 2013 the district closed 50 schools on the South and West Sides, a move that disproportionately affected poor black students. CPS vacillated on the reasons for the mass closings—from budget woes to school utilization. The 2010 census revealed that 200,000 African Americans had left the city, but officials underestimated how resistant and angry people would be about closings and the sting they felt in already underresourced schools and communities.

The aftermath is a plethora of empty school buildings in neighborhoods already stressed with foreclosures and vacancies—visible vestiges of communities. Teachers and principals still complain that the district’s promises of more resources to schools that absorbed the displaced students didn’t pan out. Accusations of CPS wanting to privatize the school system prove to be far from conspiratorial, given the steady increase of free charter schools sometimes opening in the very neighborhoods where public schools closed.

One of the closed elementary schools, Overton, was less than a block away from my Bronzeville condo. Each closed school sent its students to what the district dubbed a “receiving school.” Overton students could attend Mollison. On a purely personal, selfish level, the 2013 closing made me more depressed about the real estate market. Foreclosures and short sales had already rocked my block and Bronzeville as a whole. How would a vacant school affect property values? How would the district repurpose a closed school?

School closings captured the attention of educators, parents, activists and community residents, but a more permanent problem persists. Segregation in CPS, as well as in public school districts around the country, is double: race and class. Black professionals don’t send their children to Mollison. The school is 99.6 percent black and 91.6 percent low income. Test scores are below average. There’s no PTA. Parental engagement isn’t where it should be. Behavior issues bubble in some classrooms. This is what a typical black neighborhood school, a product of segregation, looks like in Chicago.

Mollison’s challenges go beyond the statistics. On another January morning, an eighth-grade girl who hadn’t been to school since November showed up. The school called child protective services amid rumors she lived with an older man.

For decades, Mollison students have struggled academically and come from high-poverty homes.15 In 1991, a Mollison eighth grader approached her principal about poverty and crime anxieties in the neighborhood. Fewer than two weeks later, police found the girl’s body in a nearby abandoned garage. She’d been stabbed six times.16

Kimberly Henderson, a black woman in her mid-40s with a pixie haircut and direct approach, is now the principal of Mollison and led the school during its rocky transition as a receiving school after Overton closed. In one year she moved the school from a Level 3—the lowest—to a Level 2. Her goal is Level 1, the highest. Mollison is no longer on probation, but it is far from being a top school. It’s about making leaps in student growth, which is one of the ways CPS measures success, even if the achievement of the school’s students remains below grade level.

Mollison’s walls brim with appropriate school-age platitudes—“You can change the world” and “Spread your wings.” African cloth, black art and college banners decorate the hallways. The school offers a Spanish-language class, and the teacher has taped vocabulary words all over the school for language reinforcement. International flags wave inside and outside the building. Bookcases are in nooks of the corridor. Every Friday teachers and administrators don their alumni paraphernalia for “college day.”

Inside classrooms, signs remind students to be respectful and watch their noise levels. Wide-eyed preschoolers hug new people who enter their classrooms. Third-grade teacher Ms. Love rings a bell on her desk when it’s time for students to move to the next unit. Ms. Thomas’s kindergarten/first-grade students put their hands up if a word she says rhymes. Hands down if the word doesn’t. Each Mollison classroom door displays weekly attendance achievement. Ms. Longmire plays jazz as the day commences to settle students down, and a Nelson Mandela education quote is plastered prominently above a row of computers. Most classrooms are equipped with technology—iPads, computerized smartboards instead of chalkboards. Students wear uniforms of either navy or khaki. Upper-grade boys and girls learn in separate classrooms.

Mollison is applying for authorization to institute an International Baccalaureate college-prep program for its middle schoolers. The Spanish and an upper-grade math teacher are researching a grant to travel to China to learn some best education practices.

Principal Henderson looks for student growth, demands it from the teachers, shows them how to interpret test data. When she arrived at Mollison, she implemented the additional structure she says was sorely needed. Every Friday she and Assistant Principal Janelle Thompson spend all day meeting with teachers about their lesson plans. During testing season, she emphasizes action plans to move test scores up. The duo marked their third year as a team during the 2014–2015 school year. They routinely meet about reading interventions because only 25 to 30 percent of students read at grade level. In a climate of school testing, Henderson personally tells eighth graders about the importance of testing to graduate eighth grade and to help determine the high school they will attend. She tells them: “You are smart. You need to be reading.”

“I really think that goes a long way in empowering the kids and making sure they understand the way we do what we do, and better yet, what the data tells us. That was a huge missing piece and I think that’s [true] at most schools. Kids do not understand why we’re taking the test, what the results mean; they think it’s just a number. Once they start to take pride in their own work and how they’re accomplishing things, I think you see more of an effort from them,” Henderson told me.17

She takes a no-excuses approach to the difficulties facing Mollison.

“When a school’s low achieving, it’s the adults in the building [who are the problem]. If you don’t have the right leadership, the right teachers in place who believe these kids can do it—because they can. There are some people who believe that because they’re poor, they can’t excel. So you have to confront that mind-set when you find it, and it is here. It’s in every school,” Henderson said. “I believe it’s what you do between these four walls more than what happens to kids outside. Now, when kids’ attendance is an issue—that’s something we can’t necessarily control. So I will start off by saying if a child has a serious attendance issue, that’s something that’s a little out of our control; that makes it difficult for us to move kids. I guess if a child has some kind of severe diagnosed mental or behavioral problems, then maybe [that presents a challenge]. When a kid’s misbehaving in school, it’s just generally because of something we’re not doing here in school.”

Henderson spent more than a decade teaching in Englewood, a low-income black South Side neighborhood. She firmly believes that what goes on in a classroom can trump what’s going on at home. So what if a student didn’t get homework help, guided reading or academic discipline at home? Henderson allotted time for homework at school. Doing it was more important than where it was done.

“I did not think about where my kids came from, where they were going when they left me. If Dad was at home, if he was in jail, if Mom was on drugs. None of that mattered to me. You have to believe that your instruction—while they’re here for seven hours a day—has more of an impact and it does. We use excuses. And because we use excuses, when kids don’t perform well, we think that’s acceptable? Or to be expected? And I’m not sure I buy into that. There’s very little aside from a kid not coming to school that I think we can’t overcome.”

When I ask her whether segregation is a problem in CPS and for her, Henderson referred to her own—and my—separate experiences at the historically black Howard University.

“I don’t know about the integration part. Heck, I went to an all-black college, just like you. I don’t necessarily have a problem with how the neighborhood is set up. I don’t think there’s necessarily anything wrong with that. I think it’s wrong when we don’t have the same resources. I don’t have a problem with the fact that 99.9 percent of my students are black. As long as when we look across at a school that has an opposite reality, we all have the same resources,” she explained.

She does see the grander picture of haves and have-nots in CPS. The district puts money toward selective-enrollment high schools, which get brand-new buildings downtown and on the North Side.

Public school funding in Illinois, as in other states, is a huge issue. Every CPS student—whether South Side or North Side—gets the same per-pupil dollar amount, and the debate about reforming property taxes to deal with affluent suburbs versus the struggling city is decades old. But some of the best public schools don’t rely just on CPS allocations. PTAs, fundraisers and businesses contribute to the well-being of a school. Mollison doesn’t have a PTA, which doesn’t surprise Henderson. She’s never taught at a low-performing poor black school that had one. But Mollison does have a Parent Advisory Council, which focuses on empowering the parents. Those parents have a presence inside the school, as by hosting a family game night.

Nonetheless, neighborhood schools in poor black neighborhoods can’t compete with just a per-pupil allowance. A different set of well-resourced parents makes the difference in schools.

Researchers at the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research say schools in more advantaged areas of the city serving more economically advantaged students are much more likely to improve than schools located in areas that serve high numbers of students living in poverty because neighborhoods possessing “social capital,” collective economic benefits and networks, fare better. Scholars and public educators around the country view social capital as social glue that holds schools together.

Social capital “is based on the connections and resources that families and people in the community have that they can actually use to support the schools. So if you look at the schools in the poorest areas of the city, in general, there’re very few strong institutions so you don’t have the strong community organizations. You don’t have a lot of religious participation. You don’t have churches, strong churches that can support the communities. I’m not talking about storefront churches,” Elaine Allensworth, of the Consortium on Chicago School Research, told me.18 “When you look at the very poorest neighborhoods in the city, they are really struggling to maintain strong institutions. You don’t have a lot of economic opportunity. You don’t have jobs for families or for kids. You also have problems with crime. That’s antisocial capital. Not all communities have equal resources. If you’re in a community with strong community organizations and people have the time and the connections that they can bring to bear to support the schools, it’s going to be easier to have a strong school.”

Principal Henderson sees another imbalance. She says: “When you zoom out, you’ll also see that those poor black schools also don’t have the best teachers. Also [they] don’t necessarily have administrators that can deal with that reality. There’s been research showing that the kids in the worst neighborhoods also have the worst teachers. I don’t know that you can put one over the other and say that it’s because of the community. Though poverty affects attendance in a lot of ways—that I cannot control. But again, if you’ve got the right teacher in the classroom, you can get around that. And I’ve just seen too many cases where teachers have been able to get past those inequities.”

As principal, she does her best to go to bat for her teachers—who are black and white—and make them feel appreciated in tougher circumstances so they don’t leave for higher-performing schools.

According to Gary Orfield, schools with concentrated poverty rarely compete with middle-class schools. “What really matters in schools are what is the quality and experience of your teachers, what is the level and delivery of the curriculum and what’s the peer group like and the families of the peer group. You put kids who are very well prepared together in a competitive classroom with a teacher who knows what to do and who has a curriculum that’s going to challenge those kids, and good things happen. In a high-poverty school, they face multiple problems, and one of them is there’s not even basic stability. Neither the teachers nor students stay there for very long.”

Schools need to be understood as rivers, not islands, Orfield explained. “People who live in poor neighborhoods basically don’t stay there because they want to; they stay because they don’t have other choices. And teachers who teach in them don’t want to stay either. They leave as soon as they get choices. That means there is no long-term school community that really has the essentials for creating a good educational outcome.”

Black middle-class parents have long worked within constructs of CPS to get their kids in better schools if they didn’t go the private or Catholic route. For some of my friends, the transition to school out of their neighborhood wasn’t always easy. Traveling from a less affluent black neighborhood to a more affluent white one made them feel like they lived two different lives. One friend who grew up in a rougher part of Morgan Park told me that by the time she reached eighth grade she had stopped going outside entirely and only went to the houses of school friends in Beverly. The boys she grew up with and their older brothers had become gangsters, wearing colors, twisted hats, with multiple visits to juvenile detention/group homes. “Things became increasingly sexualized, replete with all of the disrespect common in the music at the time, and all of my girlfriends started to become very sexual at an early age and had developed a penchant for stealing from the local stores. Me and my sister had lost our place, and, frankly, we didn’t care. We had moved on as well.”

My parents never considered sending me to our black neighborhood high school, which severely underperformed. Enrolling would have been as likely as me moving to the Soviet Union for boarding school. And I don’t speak Russian. Same for my Chatham friends. Everyone I knew applied for and got accepted into public schools outside of our neighborhood boundaries, which extended well beyond Chatham into rougher sections of communities.

I tested into the seventh- and eighth-grade academic center at Morgan Park High School. Back then just two other high schools offered that accelerated, competitive junior high program. By eighth grade, my course load consisted mostly of freshman classes. Morgan Park surely wasn’t the best high school in the city, but its college prep program, great counselors, respected international language program, Advanced Placement courses, sports teams and extracurricular activities made it a well-rounded experience. Hispanics from outside neighborhoods were bused in, promoting a different racial balance.

My love for school continued at Morgan Park. True to the 1990s era, boys looked like they walked off music video sets from either Boyz II Men or Jodeci. Girls rocked asymmetrical haircuts. We wore Girbauds, Champion T-shirts, carried Eddie Bauer portfolios and slung Coach bags over our shoulders. Michel’le’s “Something in My Heart” and Art of Noise’s “Moments in Love” were the slow-dance soundtracks at homecoming. Though our parents carefully curated our lives, we attended funerals and baby showers of peers and locker partners. A memorable school play written by a student took on teenage pregnancy, STDs, interracial dating and high schoolers having a good time dancing to Digital Underground. Mae Jemison, the first black female astronaut, had advanced through Morgan Park’s widely acclaimed physics program, and our school newspaper—arguably the best student paper in the city and among the top in the state—eagerly covered her visit back. Morgan Park exhibited intraracial class diversity, and I take a lot of pride in being a CPS product. All of my peers from Morgan Park attended fine colleges and universities: Spelman, Northwestern, Penn, Princeton, Tennessee State and the University of Illinois.

Still, racial transitions in the student body and administration drew citywide attention and raised questions about how far black and white parents would go to participate in school integration.

In 1990, Morgan Park’s local school council didn’t renew the contract of the white principal. The vote split along racial lines—whites for, blacks against. White students walked out in support of Principal Walter Pilditch. Angry confrontations spiraled, leading to police clashes with students. The melee made the front page of the Chicago Sun-Times.19 Several students, blacks included, were treated at nearby hospitals because they say police hit them with nightsticks. I don’t remember much about that day except being herded into the school auditorium away from the drama and buckets of tears. At the time Morgan Park was roughly 70 percent black, 20 percent white and 10 percent Hispanic. Allegations of racism were hurled at Pilditch, himself a Morgan Park graduate, and local school council members. Some black students said Pilditch ignored racism complaints. Pilditch argued that test scores were up and that he disciplined two teachers for racial or derogatory remarks. He filed a lawsuit shortly after his firing in federal court and eventually won in 1992, in part because the court ruled those district-wide local school councils had too much power in firing principals.

Morgan Park’s racial transition accelerated after Pilditch’s departure and a series of black principals arrived.

In addition to its enhanced academic offerings, Morgan Park is a neighborhood high school for the integrated Beverly area, and the attendance boundaries extended to black parts of Morgan Park. In 2014, the school was 97 percent black and 87 percent low income, hardly reflective of the integrated neighborhood’s demographic. Total student enrollment hovers around 1,300. In my day during the early 1990s, 2,000 students attended. Many white Beverly parents send their children to the local Catholic schools.

* * *

In 2009, Chicago asked for relief from desegregation efforts.

The federal court terminated the desegregation consent decree and monitoring, which required no school to be more than 35 percent white, stating that CPS demonstrated substantial good-faith compliance. “For more than 20 years the Board was dutiful in its commitment. The board filed annual reports with the Court detailing the Board’s desegregation actions, integration of school-based faculty and the remediation of other practices necessary to satisfying its commitment. The United States never challenged or complained about the Board’s efforts to bring about change, the efficacy of actions or the good faith with which it was operating,” Judge Charles P. Kocoras wrote. His opinion said that the board “eliminated all vestiges of segregation ‘to the extent practicable.’”20

The ruling meant that even CPS’s limited and feeble efforts toward desegregation would no longer be legally mandated. Indeed, over the life of Chicago’s consent decree, federal law had changed such that many believed CPS could not even use race as an admission criterion for vaunted magnet and selective-enrollment schools. District officials pretty much threw in the towel about integration, arguing it was impossible with only 8 percent white enrollment.

CPS created new socioeconomic tiers as a proxy for race:

- Median family income

- Percentage of single-parent households

- Percentage of households where English is not the first language

- Percentage of homes occupied by the homeowner

- Level of adult education attainment

- The performance of neighborhood schools in the area

It was only a matter of time before Chicago would take race out of the equation. A 2007 U.S. Supreme Court decision paved the way for the period we’re in today on race and public schools. It invalidated voluntary school desegregation plans that used race as an admission criterion; the case stemmed from school districts in Seattle, Washington and Louisville, Kentucky: Parents Involved In Community Schools v. Seattle School District, No. 1 and Meredith v. Jefferson County School Board.

“Class isn’t race and race isn’t class. They’re related but they’re different, and if you give preference on the basis of class alone, you’re going to reward new immigrants who have high human capital but low current income,” Gary Orfield told me. “Class is very poorly defined in our data systems.” People recently divorced or sick may qualify as poor, but that’s not the same as lifetime poverty.

Orfield’s national research shows that segregation is typically by race and poverty. Black and Latino students tend to be in schools with a substantial majority of poor children while whites and Asians typically are in middle-class schools.

CPS sidesteps commenting on integration. When I’ve asked, officials provide hackneyed empty rhetoric and say they want good schools for all students. Steve Bogira of the Chicago Reader regularly writes about poverty and segregation. A top CPS official called racial integration laudable but told Bogira that the district’s focus is quality for all students.

Bogira doesn’t buy that philosophy. “Given what a thorny issue desegregation is, and how difficult it would be to achieve in Chicago’s schools, it’s understandable that education activists and officials, black and white, have resigned themselves instead to trying to make separate equal. But that’s not working, either,” he writes.21 Race gaps in student achievement are most acute in black racially isolated schools.

Today CPS offers parents more high-performing high school choices for their children than it did 20 years ago. Chicago has both the best and the worst public schools in Illinois—which foments jockeying for coveted spots in the best-performing schools, especially among middle-class families. Overwrought parents of all races freak out over testing when their children are barely out of the womb. The result? White enrollment is increasing in elite public schools.

A 2014 Chicago Sun-Times investigation found more white students at selective-enrollment high schools on the city’s North Side—some as high as 41 percent. The white population in those schools climbed after the consent decree was struck down.

The increase fulfilled predictions that minority students would be edged out of the city’s top schools as a result of the judge lifting the consent decree. One parent characterized the new makeup of schools as “gated communities for children of privilege.”22

Even though CPS is only 9 percent white, at myriad magnet, selective-enrollment, gifted and classical elementary schools, that percentage is more than double. (Conversely, white students are dramatically underrepresented in charter schools, where they make up only 1.7 percent of the overall population.) Some Chicago white parents shun outstanding schools that have a significant black population. McDade (92 percent black) and Poe (91 percent black) are public schools with selective enrollment and require testing for admission. They are among the top elementary schools in the entire state and happen to be on the South Side in black neighborhoods. These are just two examples; others exist on the high school level.23

White parents may decide not to vie for slots in these high-performance schools because of the distance from their homes and housing segregation patterns in the city. These outstanding schools invalidate ideas that black children are deficient and culturally incapable of high achievement. Separate but equal doesn’t work, but that doesn’t mean black children cannot thrive in school. Even though I emphasize that segregation doesn’t work, I am not suggesting that there is something wrong with black children or black institutions. Racialized inequities are the problem.

Meanwhile, racism produces outrageous theater. Lenart is another top Illinois elementary school. In 2002, the school moved from a white South Side neighborhood to West Chatham. White parents used a code word—crime—to express their dismay about the school moving into a stable middle-class black community. Since the school moved, the white student population has decreased by more than half while the black student population continues to rise. Nevertheless, the elementary school remains a top one.

Diverse environments provide students with soft skills to succeed in an ever-evolving global society. Integration helps students of all races—including whites. Interracial contact can also reduce racial prejudice among students, and that exposure can help them later in life, in college and at work. Clearly, for some white CPS parents, diversity begins and ends when whites are the majority. Due to the city’s hypersegregation, white parents equate the South Side with danger and dysfunction. In 2013, a baseball game between two selective-enrollment high schools was canceled when some North Side parents refused to let their children travel to the South Side for the game.24 They were worried about safety. It’s infuriating to witness the prejudices of people who swear they aren’t prejudiced.

Kimberly Henderson, the Mollison principal, lives in Beverly and sends two of her children to high-performing elementary schools that require testing for entry. She grew up on the South Side, and her mother enrolled her in Catholic school instead of the neighborhood school.

“And I remember distinctly getting in trouble at school. The nun told them that I was bored, and the reason I was getting in trouble was because I was done with all my work and that they should test me,” Henderson recalls. She tested into Poe, one of the top-performing elementary schools then and now. In seventh grade, Henderson tested into one of the academic center programs.

When Henderson had children, her view shifted from that of a CPS teacher to a parent who wanted to provide the same educational path. Her son attends one of the best high schools in the state, Lane Tech High School (44 percent Hispanic, 33 percent white, 10 percent Asian and 9 percent black). Her daughters tested into Lenart and McDade. They all test extremely high and love to read.

“It was just a foregone conclusion for me—that everybody would test to get into selective-enrollment schools.”

Her fourth-grade son is the only one who attends an integrated neighborhood school—Sutherland, my alma mater, in Beverly. He has ADHD, and Henderson thinks the school can provide him with organization. Sutherland no longer has the busing program I was a part of, but it’s a strong school that’s naturally integrated because of the neighborhood.

All of those different schools make for hectic mornings in the Henderson house. Combing hair, cooking waffles, reminders of book bags and the day’s schedule. The eldest, a senior in high school, is out the door by 5:30 a.m. to take public transportation. Henderson takes her two daughters—in third and sixth grades—to the exact same bus stop in two trips because of different pickup times. Selective-enrollment schools offer busing. Finally, she drops off her youngest son at Sutherland, just a few blocks away.

“I was still kind of bummed out because we didn’t have anybody in the same school. But everybody’s school, I feel, is perfect for them,” Henderson told me.

She’s had a jam-packed half day before she pulls into the parking lot at Mollison.

Henderson doesn’t complain and is thinking ahead. She’s prepping the younger three for academic centers, which are accelerated seventh- and eighth-grade programs embedded in a high school, similar to what I did for Morgan Park.

“I knew from my own experience that being in a regular grade elementary school, there was only so much we could do in terms of the rigor. Like we can never re-create what they do in the academic center,” Henderson told me.

The family hasn’t always lived in neighborhoods with great schools, but that never factored into how she planned to map out her children’s education. When I asked her about the school choices she and her husband made, they sound a lot like what I hear from many black parents. Henderson doesn’t focus on race. All of the children attend great schools that happen to be diverse or rooted in black excellence.

A recurrent argument is how schools can even begin to think about much less fix the problems of segregation if housing isn’t addressed. Public schools merely reflect housing patterns. As long as segregation persists where people live, schools will by default be segregated. Indeed, housing plays a big factor because structural racism affects everything—housing, poverty, education, employment and so on. Our housing segregation patterns aren’t by accident, and neither are our public schools. I take to heart Principal Henderson’s no-excuses approach and her not having a problem running an all-black school. But I also see the uphill battles Mollison faces. I argue that the system purposefully leaves behind black neighborhood schools. “People basically look at the problem of segregation and say ‘It is so big; there’s no way we could solve it all so let’s do nothing.’ That’s like saying cancer or heart disease is incurable. But for some people it really can be cured. So should we say if we can’t really cure segregation, we don’t do anything about it? That’s basically the logic of Chicago and a number of big cities,” Gary Orfield told me. “Imagination has completely failed in Chicago.”

Chicago is a multiracial city where people aren’t learning together or about each other. Despite hypersegregation, the city’s diversity conceivably could open the door for interracial, interclass schools. New magnet schools across regional school boundary lines could be opened, Orfield explained.

No one solution can reverse decades of institutionalized racism. “You could take a major institution in Chicago—the Field Museum [of Natural History] or something—and create a regional magnet school together with one of the universities. How many people would want to go to that?” he asked.

Orfield suggests that nascent gentrification in some neighborhoods opens the door to support integrated neighborhoods. Changing attendance boundaries, building regional relationships for new schools or compelling the suburbs to play along by offering seats in their public schools are ideas that could work. None of these ideas is groundbreaking. Magnet schools have long promoted academic excellence while mitigating racial isolation. Connecticut, for example, has spent $2.5 billion to open new magnet schools in the Hartford region to encourage integration. Suburban districts have voluntarily offered students seats in public schools.25 In late 2014, the state of New York education chief announced grants for a voluntary integration program to foster diversity in high-poverty school districts.26

A University of Minnesota Law School report in 2013 argues that magnet schools provide a number of models for enhancing education for urban students. “A survey of results for racially diverse magnets in the Twin Cities clearly suggests that students do best in stably integrated schools—schools that do not make the transition to predominantly non-white that is so common for racially diverse schools. Further, results in several other states also suggest that there are potential benefits for the region in pursuing magnet school-University partnerships.”27

Another report by the University of Minnesota Law School—written by Myron Orfield, Gary Orfield’s brother—argues for a regional integration district. It would create a variety of magnet schools and pro-integration affordable housing programs in high-opportunity neighborhoods.28

The imagination Gary Orfield touched on is not seen in Chicago.

To be sure, CPS has money for new schools. In 2014 the city announced a new selective-enrollment high school on the North Side near the former Cabrini-Green public housing development and right around the corner from another selective-enrollment high school. The announcement hints of pandering to white middle-class parents to not leave the city and promising that their children won’t have to travel to the South Side. None of the elite testing high schools on the South Side has a significant white population.

When the controversy first raged over CPS shuttering 50 schools, I thought about the arguments in favor of closings: half-empty schools and depopulation in battered neighborhoods. Promises for better resources rang hollow. Underperforming schools closed, and students from them were transferred to equally underperforming schools a wee bit farther away. Again, this signifies no imagination. What a radical idea if CPS brought back widespread busing (currently it’s for students attending selective-enrollment elementary schools) and dispersed those students to some of the top neighborhood or at least middling schools. CPS could have used the school closings to address segregation and promote integration. After all, the schools that closed were poor and racially isolated.

Sure, the circumstances were different for me and my family and our Chatham neighborhood, but I ruminate over the integrated elementary school experience of myself and my siblings—a magnet-like program and busing that worked. Educators and politicians commemorate Brown v. Board of Education for striking down separate but equal, but half a century later, we don’t value its legacy. Instead of truly fixing school poverty and segregation in Chicago, district officials and political leaders avoid the problem and fail to provide meaningful discourse. To them, the problem is too big; that inaction implies tacit approval of separate yet unequal. And right now Chicago isn’t even exploring ideas.