{ FOUR }

Ownership Societies: The Case of France

In the previous chapter we looked at the French Revolution as a moment of emblematic rupture in the history of inegalitarian regimes. Within the space of a few years, revolutionary lawmakers tried to redefine the relations of power and property they inherited from the trifunctional scheme and to introduce a strict separation between regalian powers (henceforth to be a monopoly of the state) and property rights (ostensibly open to all). We were able to gain a sense of the magnitude of the task and of the contradictions they encountered and specifically of the way complex political and legal processes and events ultimately collided with the question of inequality and redistribution of wealth. As a result, the new proprietarian language often enshrined rights that stemmed from old trifunctional relations of domination, such as corvées and lods.

We will now look at how the distribution of property evolved in nineteenth-century France. The French Revolution opened up several possible ways forward, but the one ultimately chosen led to the development of an extremely inegalitarian form of ownership regime that endured from 1800 to 1914. This outcome was strongly assisted by the fiscal system established by the Revolution, which persisted without much change until World War I for reasons we will try to understand. Comparison with the course followed by other European countries such as the United Kingdom and Sweden (Chapter 5) will help us to understand both the similarity and diversity of European ownership regimes in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The French Revolution and the Development of an Ownership Society

What can we say about the evolution of property ownership and concentration in the century following the French Revolution? For this we are able to call on an abundance of sources. For although the Revolution of 1789 did not succeed in establishing social justice here below, it did leave us an incomparable resource for the study of wealth: namely, inheritance archives, which recorded property of many kinds, using a system of classification which itself is a reflection of proprietarian ideology. Thanks to the digitization of hundreds of thousands of inheritance records from these incomparably rich archives, it has been possible to study in detail the evolving distribution of wealth of all kinds (land, buildings, tools and equipment, stocks, bonds, shares of partnerships, and other financial investments) from the time of the Revolution to the present. The results presented here are the product of a large joint research effort, which drew extensively on the Paris archives in particular. National tax records from different periods were also used, along with records from département archives from the beginning of the nineteenth century on.1

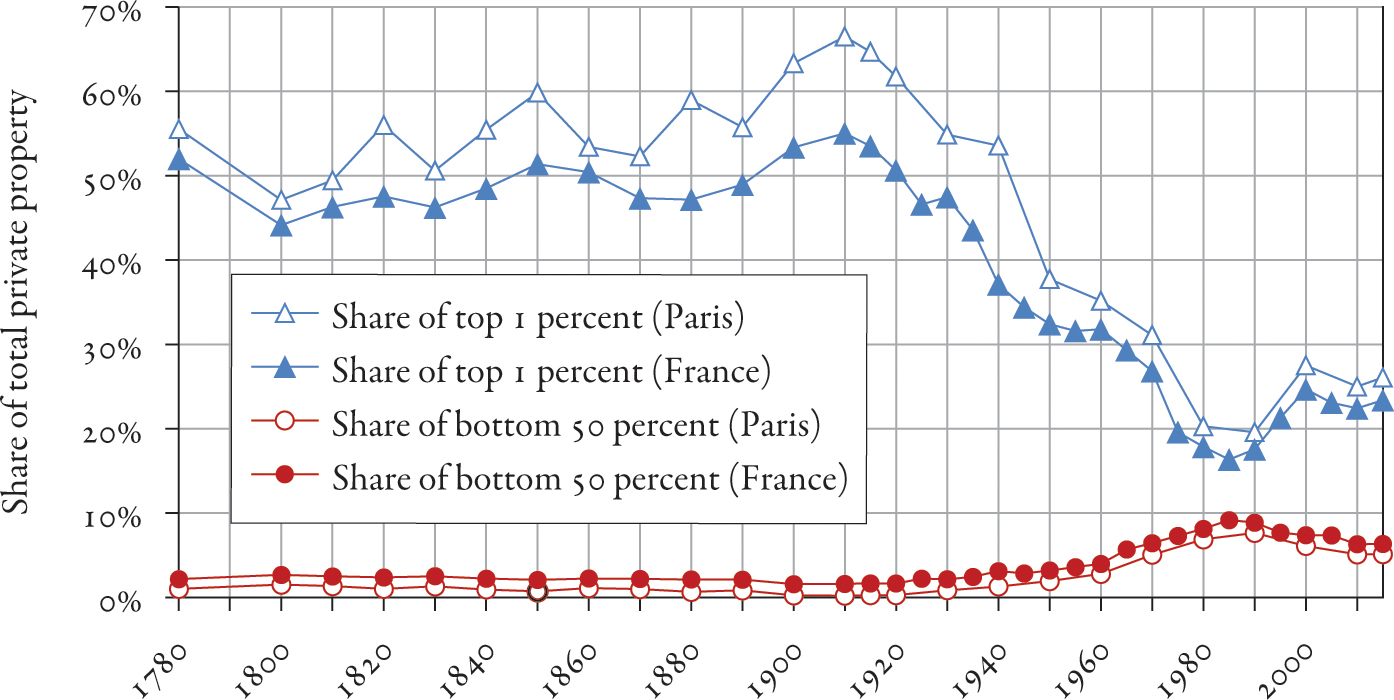

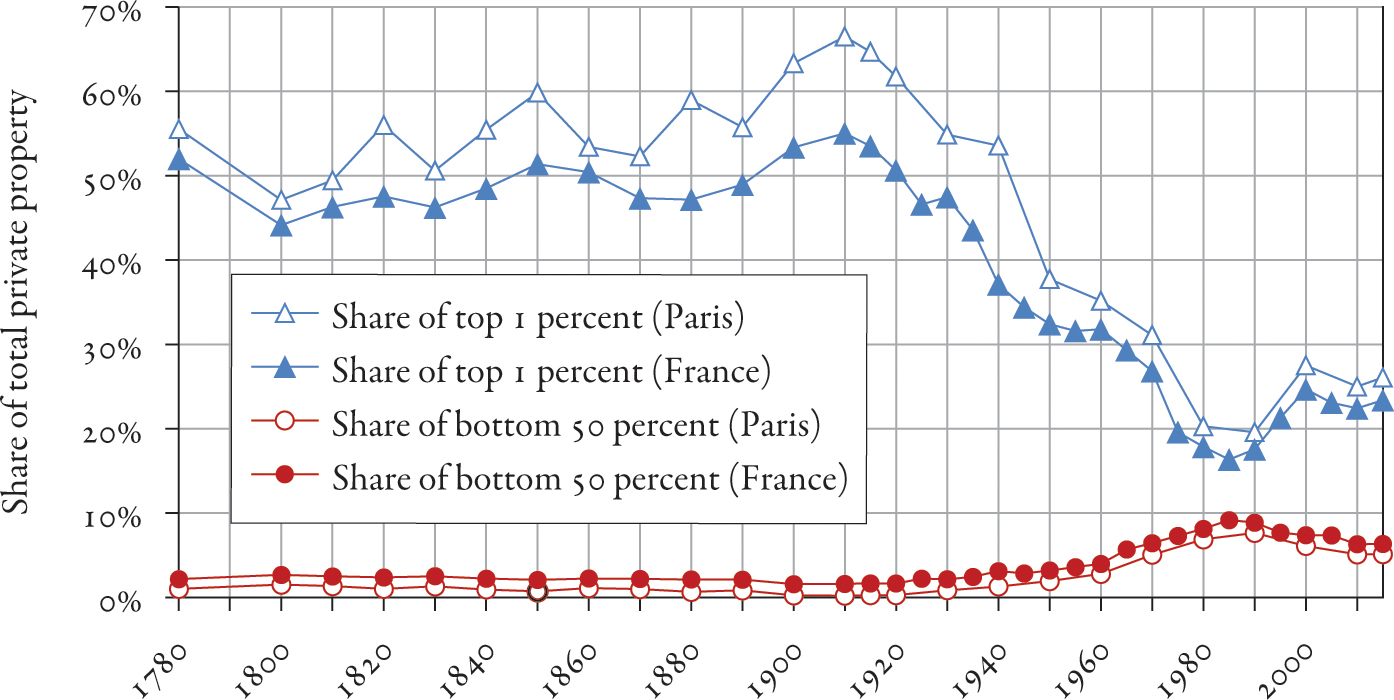

The most striking conclusion is this: the concentration of private property, which was already extremely high in 1800–1810, only slightly lower than on the eve of the Revolution, steadily increased throughout the nineteenth century and up to the eve of World War I. Concretely, looking at France as a whole, we find that the top centile of the wealth distribution (that is, the wealthiest 1 percent) owned roughly 45 percent of private property of all kinds in the period 1800–1810; by 1900–1910 this figure had risen to almost 55 percent. The case of Paris is especially noteworthy: there, the wealthiest 1 percent owned nearly 50 percent of all property in 1800–1810 and more than 65 percent on the eve of World War I (Fig. 4.1).

Indeed, wealth inequality rose even more rapidly in the Belle Époque (1880–1914). In the decades prior to World War I, there seemed to be no limit to the concentration of fortunes. Looking at these curves, one cannot help wondering how high the concentration of private property might have risen had the two world wars and the violent political cataclysms of the twentieth century not occurred. There is also good reason to wonder whether those cataclysms and wars were not themselves consequences, at least in part, of the extreme social tensions due to rising inequality. I will have more to say about this in Part Three.

Several points deserve emphasis. First, it is important to bear in mind that the concentration of wealth has always been extremely high in countries like France, not only in the nineteenth century but also in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Although the top centile share decreased considerably over the course of the twentieth century (from 55–65 percent of total wealth in France and Paris on the eve of 1914 to 20–30 percent after 1980), the share owned by the poorest 50 percent has always been extremely low: roughly 2 percent in the nineteenth century and a little over 5 percent today (Fig. 4.1). Thus the poorest half of the population—a vast social group fifty times larger than the top centile, by definition—owned something on the order of one-thirtieth the wealth of the top 1 percent in the nineteenth century. This means that the average wealth of the top centile was roughly 1,500 times the average wealth of the bottom 50 percent. Similarly, the poorest half owned roughly one-fifth the wealth of the top centile in the late twentieth century, as it does today (which implies that the average wealth of a 1 percenter is “only” 250 times that of a person in the bottom half of the distribution). Note, moreover, that in both periods we find the same extreme inequality within each age cohort, from youngest to oldest.2 These orders of magnitude are important, because they tell us that we should not overestimate the extent of the diffusion of ownership that has taken place over the past two centuries: the egalitarian ownership society—or even, more modestly, a society in which the poorest half of the population owns more than a token share of the wealth—has yet to be invented.

FIG. 4.1. The failure of the French Revolution: The rise of proprietarian inequality in nineteenth-century France

Interpretation: In Paris, the wealthiest 1 percent held roughly 67 percent of all private property in 1910, compared with 49 percent in 1810 and 55 percent in 1780. After a slight decrease during the French Revolution, the concentration of wealth increased in France (and even more in Paris) during the nineteenth century to the eve of World War I. Over the long run, inequality fell after the two world wars (1914–1945) but not after the French Revolution. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Reducing Inequality: The Invention of a “Patrimonial Middle Class”

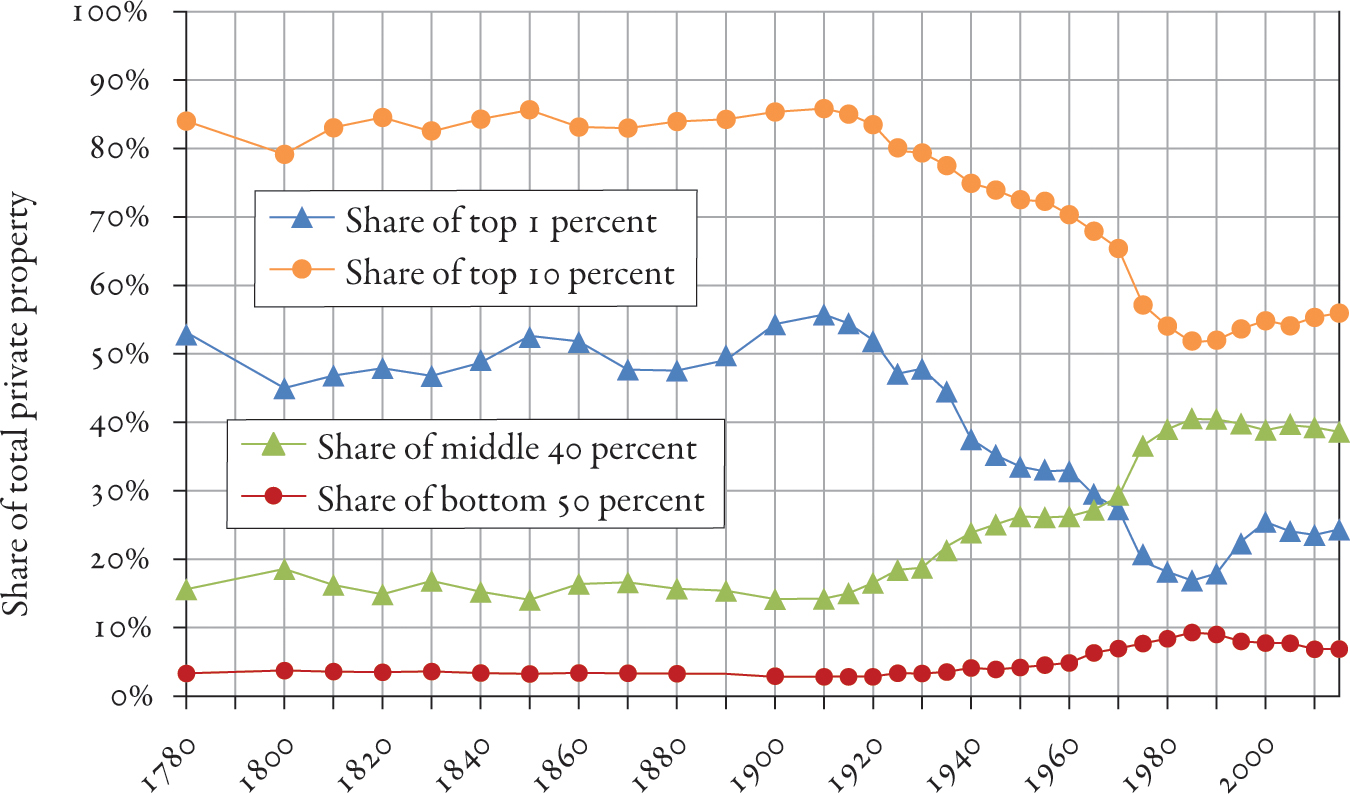

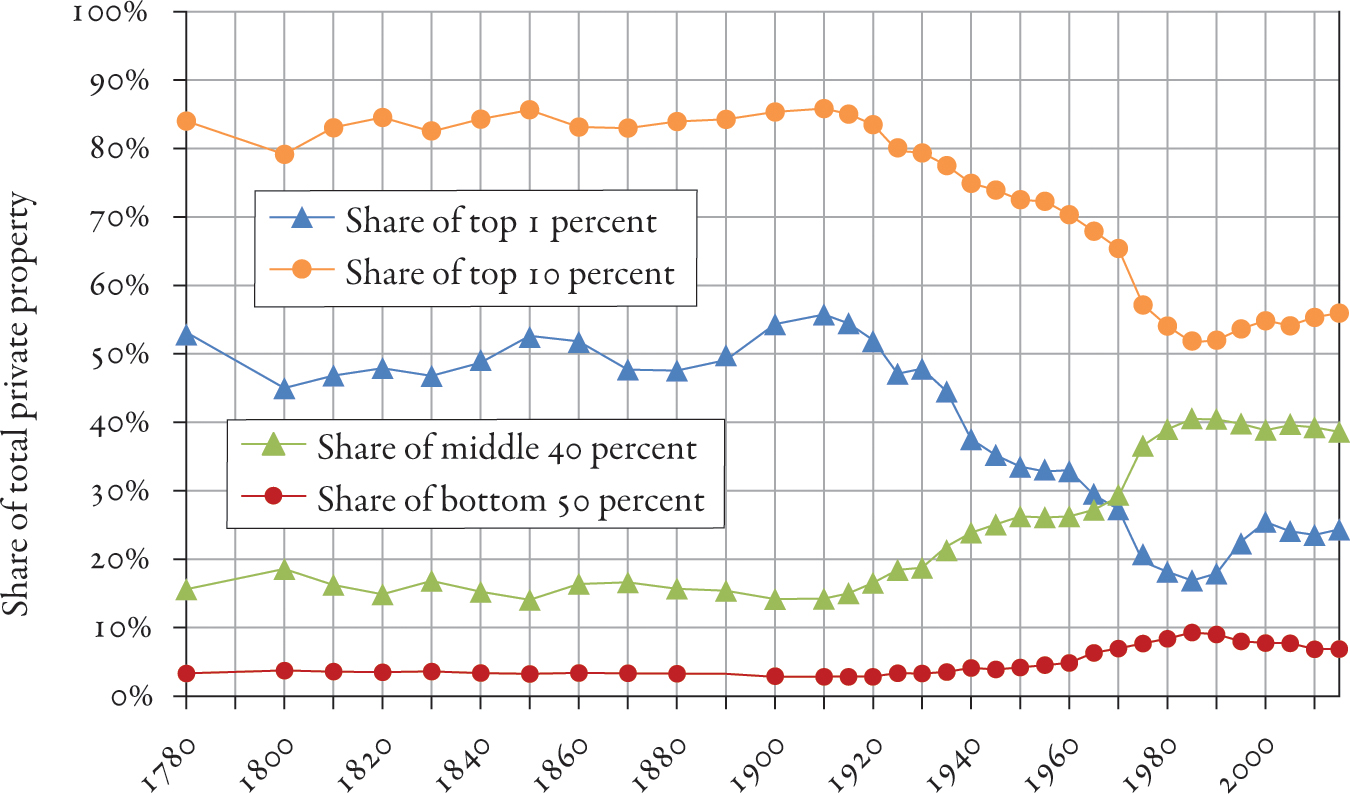

When we look at the evolution of the distribution of wealth in France, it is striking to find that in the nineteenth century, the “upper classes” (that is, the wealthiest 10 percent) owned between 80 and 90 percent of the wealth, while today they own between 50 and 60 percent—still a significant share (Fig. 4.2). For comparison, the concentration of income, including both income from capital (which is as concentrated as ownership of capital, indeed slightly higher) and income from labor (which is significantly less unequally distributed), has always been less extreme: the top 10 percent of the income distribution claimed about 50 percent of total income in the nineteenth century, compared with 30–35 percent today (Fig. 4.3).

Nevertheless, it is a fact that wealth inequality has decreased over the long run. However, this profound transformation has not benefited the “lower classes” (the bottom 50 percent), whose share remains quite limited. The benefits have gone almost exclusively to what I have called the “patrimonial (or property-owning) middle class,”* by which I mean the 40 percent in the middle of the distribution, between the poorest 50 percent and the wealthiest 10 percent, whose share of total wealth was less than 15 percent in the nineteenth century and stands at about 40 percent today (Fig. 4.2). The emergence of this “middle class” of owners, who individually are not very rich but collectively over the course of the twentieth century acquired wealth greater than that owned by the top centile (with a concomitant decrease in the top centile’s share), was a social, economic, and political transformation of fundamental importance. As we will see, it explains most of the reduction of wealth inequality over the long run in France and most other European countries. Furthermore, this deconcentration of ownership does not seem to have impaired innovation or economic growth—quite the opposite: the emergence of the “middle class” went hand in hand with greater social mobility, and growth since the middle of the twentieth century has been stronger than ever before, in particular stronger than it was before 1914. I will come back to this, but for now the key point to notice is that this deconcentration of wealth did not begin until after World War I. Until 1914, wealth inequality seemed to be growing without limit in France, and especially in Paris.

FIG. 4.2. The distribution of property in France, 1780–2015

Interpretation: The share of the wealthiest 10 percent of all private property (real estate, professional equipment, and financial assets, net of debt) varied from 80 to 90 percent in France between 1780 and 1910. Deconcentration of wealth began after World War I and ended in the early 1980s. The principal beneficiary was the “patrimonial middle class” (the 40 percent in the middle of the distribution), here defined as the group between the “lower class” (bottom 50 percent) and the “upper class” (wealthiest 10 percent). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Paris, Capital of Inequality: From Literature to Inheritance Archives

The evolution that took place in Paris between 1800 and 1914 is particularly emblematic, because the capital was both the seat of the largest fortunes and the site of the most extreme inequalities. This reality stands out clearly in literature, especially the classic novels of the nineteenth century, as well as in the inheritance archives (Fig. 4.1).

FIG. 4.3. The distribution of income in France, 1780–2015

Interpretation: The share of the top 10 percent of earners in total income from both capital (rent, dividends, interest, and profits) and labor (wages, nonwage income, pensions, and unemployment insurance) was about 50 percent in France from 1780 to 1910. Deconcentration began after World War I, with the “lower class” (bottom 50 percent) and “middle class” (middle 40 percent) as the main beneficiaries at the expense of the “upper class” (top 10 percent). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

At the end of the nineteenth century, about 5 percent of the population of France lived in Paris (2 million people out of a total population of about 40 million), but residents of the capital owned about 25 percent of the country’s private wealth. Put differently, the average Parisian was five times wealthier than the average citizen of France. Paris was also the place where the gap between the poorest and the wealthiest citizens was the largest. In the nineteenth century, half of the people who died in France had no property to pass on. In Paris, the percentage who died propertyless varied from 69 to 74 percent over the period 1800–1914, with a slight upward trend. In practice, this group included people whose personal effects (furniture, clothing, dinnerware) had such little market value that the authorities saw no reason to record the amount. When meager belongings went entirely to cover the costs of burial or repay debts, heirs might choose to renounce the inheritance and file no declaration. Still, it is striking that among the estates recorded in the archives, we find many that are extremely small. The law required both the authorities and the heirs to register even very small estates, failing which the heirs’ property rights might not be recognized. This could have serious consequences: specifically, the police could not be called if unregistered property was pilfered. If a person inherited a building or business or financial assets, it was essential to file an estate declaration.

Among the 70 percent of Parisians who died propertyless in the nineteenth century was Balzac’s memorable fictional character Père Goriot, who, according to the novelist, died in 1821, abandoned by his daughters, Delphine and Anastasie, in the most abject poverty. His landlord, Madame Vauquer, dunned Rastignac for Goriot’s unpaid room and board, and he also had to pay the cost of burial, which by itself exceeded the value of the old man’s personal effects. Yet Goriot had amassed a fortune in the pasta and grain trade during the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars before spending it all to ensure that his two daughters would marry into good Parisian society. Unlike him, many who died with nothing had never owned anything and died as poor as they had lived. Strikingly, the percentage of Parisians who died with nothing to pass on to their heirs was just as high a century later in 1914, on the eve of the war, despite the considerable growth of France’s wealth and industrial development since the era of Balzac and Père Goriot.3

At the other end of the scale, Belle Époque Paris was also the place where the greatest wealth was concentrated: the wealthiest 1 percent of decedents alone accounted for half the value of all bequests in the 1810s as well as almost two-thirds a century later.4 The share of the wealthiest 10 percent was 80–90 percent of the total in the period 1800–1914 and more than 90 percent in Paris, in both cases with an upward trend.

To sum up, nearly all property was concentrated in the top decile and most of it in the top centile, while the vast majority of the population owned nothing. For a more concrete sense of inequality in Paris at the time, note that, according to the cadastre, almost no one in Paris owned an individual apartment before World War I. In other words, one normally owned an entire building (or several buildings), or else one owned nothing and paid rent to a landlord.

It was this hyperconcentration of wealth that led the sinister Vautrin to explain to young Rastignac that he had best not count on the study of law if he wished to succeed in life. The only way to achieve a comfortable position was to lay hands on a fortune by whatever means were available. Vautrin’s lecture, replete with comments on the income of lawyers, judges, and landlords, reflected more than just Balzac’s obsession with money and wealth (he himself was heavily in debt after a series of bad investments and wrote constantly in the hope of climbing out of his hole). The evidence collected from the archives suggests that Balzac was painting a fairly accurate picture of the distribution of income and wealth in 1820 and, more broadly, in the period 1800–1914. Vautrin’s lecture perfectly captured the ownership society—that is, a society in which access to comfort, high society, status, and political influence was almost entirely determined by the size of one’s fortune.5

Portfolio Diversification and Forms of Property

It is important to note that this extreme concentration of wealth, which grew more extreme over the long nineteenth century, took place in a context of modernization and extensive transformation of the very forms in which wealth was held; economic and financial institutions were reshaped as portfolios became increasingly international. The very detailed inheritance records we have gathered show that Parisian fortunes had become increasingly diversified by the end of the period. In 1912, 35 percent of Parisians’ wealth consisted of real estate (24 percent in Paris and 11 percent in the provinces); 62 percent financial assets; and barely 3 percent furniture, precious objects, and other personal effects (Table 4.1). The preponderance of financial assets reflects the growth of industry and the importance of the stock market, with investment not only in manufacturing (where textiles were on the brink of being overtaken by steel and coal at the end of the nineteenth century and then by chemistry and automobiles in the twentieth) but also in food processing, railroads, and banking—and it was the banking sector that was doing particularly well.

|

TABLE 4.1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Composition of Parisian wealth in the period 1872–1912 (in percent) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Real estate (buildings, houses, agricultural land, etc.) |

Paris real estate |

Provincial real estate |

Financial assets (equity, bonds, etc.) |

French equity (stocks) |

Foreign equity (stocks) |

French private bonds |

Foreign private bonds |

French government bonds |

Foreign government bonds |

Other financial assets (deposits, cash, etc.) |

Total foreign financial assets |

Furniture, precious objects, etc. |

||||||||||||||

|

Composition of total wealth |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1872 |

41 |

28 |

13 |

56 |

14 |

1 |

17 |

2 |

10 |

3 |

9 |

6 |

3 |

|||||||||||||

|

1912 |

35 |

24 |

11 |

62 |

13 |

7 |

14 |

5 |

5 |

9 |

9 |

21 |

3 |

|||||||||||||

|

Composition of the largest 1 percent of estates |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1872 |

43 |

30 |

13 |

55 |

15 |

1 |

14 |

2 |

9 |

4 |

10 |

7 |

2 |

|||||||||||||

|

1912 |

32 |

22 |

10 |

66 |

15 |

10 |

14 |

5 |

4 |

10 |

8 |

25 |

2 |

|||||||||||||

|

Composition of the next-largest 9 percent |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1872 |

42 |

27 |

15 |

56 |

13 |

1 |

21 |

2 |

10 |

2 |

7 |

5 |

2 |

|||||||||||||

|

1912 |

42 |

30 |

12 |

55 |

11 |

2 |

14 |

4 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

14 |

3 |

|||||||||||||

|

Composition of the next-largest 40 percent |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1872 |

27 |

1 |

26 |

62 |

12 |

1 |

23 |

1 |

14 |

2 |

9 |

4 |

11 |

|||||||||||||

|

1912 |

31 |

7 |

24 |

59 |

12 |

1 |

20 |

2 |

10 |

4 |

10 |

7 |

10 |

|||||||||||||

|

Interpretation: In 1912, real estate accounted for 35 percent of total Parisian wealth, financial assets for 62 percent (including 21 percent for foreign financial assets), and for furniture and precious objects, 3 percent. Of the largest 1 percent of fortunes, the share of financial assets rose to 66 percent (of which 25 percent were foreign). Sources: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 62 percent of wealth held in the form of financial assets was itself quite varied: 20 percent consisted of shares in firms (whether listed on the stock exchange or not), of which 13 percent was invested in French firms and 7 percent foreign firms; 19 percent consisted of private debt instruments (including notes, bonds, and other commercial paper; 14 percent French and 5 percent foreign); 14 percent was public debt (that is, government bonds; 5 percent French and 9 percent foreign); and 9 percent consisted of other financial assets (deposits, cash, miscellaneous shares, and so on). This looks like the sort of well-diversified portfolio one might find in a modern finance textbook, except that this was reality as reflected in Paris inheritance records in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For each deceased person one can identify exactly which stocks and bonds were held in which firms and which sectors.

Two additional results are worth noting. First, the largest fortunes had an even larger share of financial assets than the others. In 1912, the top 1 percent of fortunes consisted of 66 percent financial assets, compared with 55 percent for the next 9 percent. Among the wealthiest 1 percent of Parisians, who alone owned more than two-thirds of all wealth in 1912, real estate accounted for barely 22 percent of their assets and provincial real estate just 10 percent, whereas stocks alone accounted for 25 percent, private-sector bonds for 19 percent, and public-sector bonds and other financial assets for 22 percent.6 The preponderance of stocks, bonds, bank deposits, and other monetary assets over real estate reflects a profound reality: the ownership elite of the Belle Époque was primarily a financial, capitalist, and industrial elite.

Second, foreign financial investments grew enormously between 1872 and 1912. Their share of Parisian wealth rose from 6 to 21 percent. This evolution is particularly noticeable in the largest 1 percent of fortunes, where most international assets were held: the share of foreign investment among their assets rose from 7 percent in 1872 to 25 percent in 1912, compared with just 14 percent for the 90th–99th percentile of wealth and barely 5 percent for the 50th–90th percentile (Table 4.1). In other words, only the largest portfolios contained substantial shares of foreign assets; domestic assets accounted for a larger proportion of smaller fortunes.

The spectacular growth of foreign investment, whose share more than tripled in forty years, involved all types of instruments, including foreign public debt, whose share in the largest 1 percent of fortunes rose from 4 to 10 percent in the period 1872–1912. Of particular interest are the famous Russian loans, which expanded rapidly after the French Republic signed a military and economic treaty with the czarist empire in 1892. But many other foreign bonds also figured in French portfolios (especially those of European states and also Argentina, the Ottoman Empire, China, Morocco, and so on, sometimes in connection with colonial appropriation strategies). French investors earned solid returns on their foreign lending, often with government guarantees (which were thought to be golden prior to the shocks of World War I and the Russian revolution). The share of foreign private-sector stocks and bonds increased even more rapidly, from 3 to 15 percent of total assets in the richest 1 percent of portfolios between 1872 and 1912. There were investments in the Suez and Panama Canals; Russian, Argentine, and American railroads; Indochinese rubber; and countless other companies around the world.

The Belle Époque (1880–1914): A Proprietarian and Inegalitarian Modernity

These results are essential, because they show that the upward trend in the concentration of wealth in France and Paris over the long nineteenth century, and especially the Belle Époque (1880–1914), was a phenomenon of “modernity.”

If we look at this period from a distance, through the distorting lens of the early twenty-first century—the age of the digital economy, of start-ups and boundless innovation—we might be tempted to view the hyper-inegalitarian society of the eve of World War I as the culmination of a bygone era, a static world of quiet estates of little relevance to today’s supposedly more dynamic and meritocratic societies. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the wealth of the Belle Époque had little in common with that of the Ancien Régime or even the era of Père Goriot, César Birotteau, or the Parisian bankers of the 1820s, whom Balzac describes so well (and who in any case had a dynamism of their own).

In reality, capital is never quiet and was not quiet in the eighteenth century, a time of rapid demographic, agricultural, and commercial development and large-scale renewal of elites. Balzac’s world was not tranquil either—quite the opposite. If Goriot was able to make a fortune in pasta and grain, it was because he had no peer when it came to identifying the best wheat, perfecting production technologies, and setting up warehouses and distribution networks so that his merchandise could be delivered to the right place at the right time. While lying on his deathbed in 1821, he was still thinking up juicy strategies for investing in Odessa on the shores of the Black Sea. Whether property took the form of factories and warehouses in 1800 or heavy industry and high finance in 1900, the crucial fact is that it was always in perpetual motion even as it was becoming ever more concentrated.

César Birotteau, another Balzac character emblematic of the ownership society of his day, was a brilliant inventor of perfumes and cosmetics, which Balzac tells us were all the rage in Paris in 1818. The novelist had no way of knowing that nearly a century later, in 1907, another Parisian, the chemist Eugène Schueller, was about to perfect a very useful hair dye (initially named “L’Auréale,” after a female hair style of the time that was reminiscent of an aureole). Schueller’s line of products inevitably calls to mind that of Birotteau. In any case, in 1936 Schueller founded a company known as L’Oréal, which in 2019 is still the world leader in cosmetics. Birotteau took a different route. His wife tried to persuade him to reinvest the profits from his perfume factory in placid country estates and solid government bonds, as Goriot did when he sold his business and set about marrying off his daughters. But Birotteau wouldn’t hear of it: instead, he set out to triple his fortune by investing in real estate in the Madeleine district, which was just taking off in the 1820s. He ended up bankrupt, which reminds us that there is nothing particularly tranquil about investing in real estate. Other audacious promoters have been more successful, including Donald Trump, who after plastering his name on skyscrapers in New York and Chicago worked his way up to occupying the White House in 2016.

Between 1880 and 1914 the world was in perpetual flux. The automobile, the electric light, the trans-Atlantic steamship, the telegraph, and radio—all were invented in the space of a few decades. The economic and social consequences of those inventions were surely as important as those of Facebook, Amazon, and Uber. The point is crucial, because it shows that the hyper-inegalitarianism of the prewar era was not a consequence of a bygone era with little or no similarity to today’s world. In fact, the Belle Époque resembles today’s world in many ways, even if essential differences remain. It was also “modern” in its financial infrastructure and forms of ownership. Not until the very end of the twentieth century do we find levels of stock-market capitalization as high as those seen in Paris and London in 1914 (relative to national output or income). Foreign investments by French and British property owners of the day have never been equaled (again relative to a year of output or income, which is the least preposterous way of making this type of historical comparison). The Belle Époque, especially in Paris, embodies the modernity of the first great financial and commercial globalization the world had ever seen—a century before the globalization of the late twentieth century.

Yet this was also an intensely inegalitarian society, in which 70 percent of the population owned nothing at death and 1 percent of the deceased owned nearly 70 percent of all there was to own. The concentration of property was considerably greater in Paris in 1900–1914 than it was in 1810–1820, the era of Père Goriot and César Birotteau, and even more extreme than it was in the 1780s, on the eve of the Revolution. Recall that it is difficult to estimate accurately how wealth was distributed before 1789, partly because we do not have comparable inheritance records and partly because the very idea of property had changed (jurisdictional privileges disappeared and the distinction between regalian rights and property rights sharpened). By using available estimates of the redistribution carried out during the Revolution, we can, however, state that the share of property of all kinds held by the top centile on the eve of the Revolution was just slightly above that of 1800–1810 and considerably lower than in the Belle Époque (Fig. 4.1). In any case, in view of the extreme concentration of wealth observed in 1900–1914 when the top decile in Paris held more than 90 percent and the top centile nearly 70 percent, it is hard to imagine a higher level in the Ancien Régime, despite the limitations of the sources.

The fact that the concentration of wealth could rise so rapidly and to such a high level in the period 1880–1914, a century after the abolition of privileges in 1789, is an arresting result. It raises questions for the future and for the analysis of what took place from 1980 until today. It is a discovery that made a deep impression on me both as a researcher and as a citizen. My colleagues and I did not expect to find such a large and rapid increase when we began our work on the inheritance archives, particularly since many contemporaries did not describe Belle Époque society in these terms. Indeed, the political and economic elites of the Third Republic liked to describe France as a country of “smallholders,” which the French Revolution had made profoundly egalitarian once and for all. The fiscal and jurisdictional privileges of the nobility and clergy had in fact been abolished by the Revolution and were never restored (not even during the Restoration of 1815, which continued to rely on the tax system it inherited from the Revolution, with the same rules for all). But that did not prevent the concentration of property and economic power from attaining a level at the beginning of the twentieth century even higher than under the Ancien Régime—not at all what a certain Enlightenment optimism had led people to expect. Think, for example, of the words of Condorcet, who asserted in 1794 that “fortunes tend naturally toward equality” once one eliminates “artificial means of perpetuating them” and establishes “freedom of commerce and industry.” Between 1880 and 1914, even though numerous signs suggested that the forward march toward greater equality had long since been halted, republican elites largely continued to believe in progress.

The Tax System in France from 1880 to 1914: Tranquil Accumulation

How do we explain the inegalitarian turn in the period 1880–1914 and then the reduction of inequality over the course of the twentieth century? Now that another inegalitarian turn has taken place in the 1980s, what can history teach us about how to deal with it? We will be returning to these questions again and again, especially when we study the crisis of ownership society following the shocks of 1914–1945 and the challenges of communism and social democracy.

For now, I simply want to insist on the fact that the inegalitarian turn of 1800–1914 was greatly facilitated by the tax system established during the French Revolution. In broad outline this remained in use without major changes until 1901 and, to a great extent, until World War I. The system adopted in the 1790s rested on two main components: first, a system of droits de mutation (sales tax on property and duties on inheritance and gifts), and second, a set of four direct taxes, which came to be called les quatre vieilles (the four old ladies) on account of their exceptional longevity.

The droits de mutation, which belonged to the larger category of droits d’enregistrement (registration fees), were fees charged for recording property transfers, that is, changes in the identity of the owners of a property. They were established by the Constitution of Year VIII (1799). Revolutionary legislators took care to distinguish between mutations à titre onéreux (that is, transfers of property in exchange for cash or other consideration—in other words, sales) and mutations à titre gratuit (that is, transfers without payment, a category that included inheritances, called mutations par décès, as well as gifts inter vivos). The droits de mutations à titre onéreux replaced the seigneurial lods of the Ancien Régime and, as noted earlier, continue to be applied to real estate transactions to this day.

The tax on direct-line bequests—that is, between parents and children—was set at the very low rate of 1 percent in 1799. Furthermore, it was an entirely proportional tax: every inheritance was taxed at the same 1 percent rate, regardless of its size, and no portion was exempt. The proportional rate did vary with degree of kinship: the tax on nondirect heirs, such as brothers, sisters, cousins, and so on, as well as on bequests to nonrelatives, was slightly higher than on direct bequests; but it never varied with the size of the inheritance. The possibility of introducing a progressive rate schedule or a higher tax on direct bequests was debated many times, especially after the revolution of 1848 and then again in the 1870s after the advent of the Third Republic, but nothing was ever done.7

In 1872, an attempt was made to increase the tax on the largest bequests from parents to children to 1.5 percent. The reform was modest, but both the legislative committee and the entire assembly flatly rejected it, invoking the natural right of direct descendants: “When a son succeeds his father, it is not strictly speaking a transmission of property that takes place; it is merely continued enjoyment of the property,” said the authors of the Code Civil (or Napoleonic Code). “If applied in an absolute sense, this doctrine would exclude any tax on direct bequests; at the very least it requires extreme moderation in setting the rate.”8 In this instance, a majority of deputies felt that a rate of 1 percent satisfied the requirement of “extreme moderation” but that a rate of 1.5 percent would have violated it. For many deputies, a hike in the rate risked unleashing a dangerous escalation in the demand for redistribution. If they were not careful, this might ultimately undermine private property and its natural transmission.

In hindsight, it is easy to make fun of this conservatism. Inheritance tax rates on the largest fortunes reached much higher levels in most Western countries in the twentieth century (at least 30–40 percent, and sometimes as high as 70–80 percent, for decades). This did not lead to social disintegration or undermine property rights, nor did it reduce economic dynamism and growth—quite the opposite. Certainly, these political positions reflected interests, but more than that they reflected a plausible proprietarian ideology or at any rate an ideology with a sufficiently powerful appearance of plausibility. The point that emerges clearly from these debates is the risk of escalation. At the time, for a majority of deputies the purpose of the inheritance tax was to record ownership and protect property rights; it was in no way intended to redistribute wealth or reduce inequality. Once one moved outside this framework and began to tax the largest direct bequests at substantial rates, there was a danger that the Pandora’s box of progressive taxation would never be closed. Unduly progressive taxes would lead to political chaos that would ultimately harm the most modest members of society, if not society itself. That, at least, was one of the propositions by which fiscal conservatism was justified.

Note, too, that the establishment of droits de mutation in the 1790s went hand in hand with the development of an impressive cadastral system: a register in which all property and all changes of ownership could be listed. The scope of the task was immense, especially since the property law was supposed to apply to everyone, independent of social origins, in a country of nearly 30 million people (by far the most populous in Europe) that covered a vast territory in a time when means of transport were limited. This ambitious project rested on a theory of power and property that was just as immense: it was hoped that state protection of property rights would lead to economic prosperity, social harmony, and equality for all. There was no reason to take the risk of spoiling everything by indulging egalitarian fantasies when the country had never been as prosperous and its power extended throughout the world.

Growing numbers of other political actors nevertheless favored other options, such as a voluntary system for limiting wealth inequality and enabling large numbers of people to acquire property. As early as the late eighteenth century, people like Graslin, Lacoste, and Paine were proposing specific and ambitious tax reforms. During the nineteenth century, new inequalities became visible as industry expanded in the 1830s, and these lent legitimacy to calls for redistribution. Yet it was no easy task to put together a majority coalition around issues of redistribution and progressive taxation. In the early decades of the Third Republic and universal suffrage, the main issues were the republican regime itself and the place of the Church in it. In addition, peasants and other rural dwellers, including some who were not very rich, were wary of the ultimate designs of socialists and urban proletarians, whom they suspected of wanting to do away with private property altogether. Indeed, their fears were not totally unfounded, and the wealthy did not shrink from stoking them to frighten the less well-off. Progressive taxation has never been and will never be as uncontroversial as some people believe. Even with universal suffrage, a majority coalition in favor of progressive taxation does not come magically into existence. Because political conflict is multidimensional and the issues are complex, coalitions cannot be assumed and must be built; the ability to do so depends on mobilizing shared historical and intellectual experience.

Not until 1901 was the sacrosanct principle of proportionality in taxation finally undone. The law of February 25, 1901, established a progressive tax on inheritances, the first progressive tax adopted in France. A progressive tax on income followed with the law of July 15, 1914. Both taxes occasioned lengthy parliamentary debates, and it was the French Senate—the more conservative of the two chambers, because rural areas and notables were overrepresented in it—that delayed adoption of the progressive inheritance tax, which the Chamber of Deputies had passed as early as 1895. Note in passing that it was not until the advent of the Fourth Republic in 1946 that the Senate lost its veto power, leaving the last word to deputies elected by direct universal suffrage, which made it possible to move forward in several areas of social and fiscal legislation.

The fact remains that the tax rates established by the law of 1901 were extremely modest: the rate on direct-line bequests was 1 percent in the majority of cases, as it had been under the proportional regime; it rose to a maximum of 2.5 percent on the portion of an estate above 1 million francs per heir (which applied to just 0.1 percent of all estates). The highest rate was raised to 5 percent in 1902 and then to 6.5 percent in 1910 to contribute to the financing of another law providing for “worker and peasant retirements” adopted that same year. Although it was not until after World War I that the rates applicable to the largest fortunes attained more substantial levels (several tens of percent) and “modern” fiscal progressivity was put in place, a decisive step was taken in 1901, and perhaps an even more decisive one in 1910, because the decision to establish an explicit relationship between a more progressive inheritance tax and paying for worker pensions expressed a clear desire to reduce social inequality generally.

To sum up, the inheritance tax had only a marginal effect on the accumulation and transmission of large fortunes in the period 1800–1914. The law of 1901 nevertheless marked an important change in fiscal philosophy regarding inheritances by introducing progressivity, whose effects began to be fully felt in the interwar years.

The “Quatre Vieilles,” the Tax on Capital, and the Income Tax

Let us turn now to the progressive income tax introduced in 1914. Recall that the four direct taxes created by revolutionary legislators in 1790–1791 (the quatre vieilles) did not depend directly on the income of the taxpayer; this was their essential characteristic.9 Bluntly rejecting the inquisitorial procedures associated with the Ancien Régime, revolutionary legislators, who probably also wished to spare the burgeoning bourgeoisie from paying too much in taxes, opted for what was called an “indicial” tax system because each tax was based not on income but on “indices” intended to measure the capacity of each taxpayer to pay; income never had to be declared.10

For instance, the contribution sur les portes et fenêtres, or “doors and windows tax,” was based on the number of doors and windows in the taxpayer’s principal residence, an index of wealth that, from the taxpayer’s point of view, had the great merit of allowing the tax collector to determine the amount due without entering the taxpayer’s home, much less peering into his account books. The contribution personnelle-mobilière (corresponding to today’s residential tax) was based on the rental value of each taxpayer’s principal residence. Like the other direct taxes (apart from the doors and windows tax, which was finally eliminated in 1925), it became a local tax when the national income tax system was established in 1914–1917, and to this day it continues to finance local and regional governments.11 The contribution des patentes (today’s local business tax) was paid by artisans, merchants, and manufacturers, with different schedules for each profession based on the size of the enterprise and the equipment employed; it was not directly linked to actual profits, which did not have to be declared.

Finally, the contribution foncière, corresponding to today’s land tax (taxe foncière), was levied on the owners of real estate, including homes and buildings as well as land, forests, and so on, based on the rental value (equivalent annual rental income) of the property, regardless of its use (whether personal, rental, or professional). The rental value, like that used in the calculation of the contribution personnelle-mobilière, did not have to be declared by the taxpayer. It was set on the basis of surveys conducted every ten to fifteen years by the tax authorities, who catalogued the country’s real estate, taking note of new construction, recent sales, and various other additions to the cadastre. Since there was virtually no inflation in the period 1815–1914 and prices evolved very slowly, it was felt that periodic adjustments were sufficient, especially since this spared taxpayers the trouble of filing declarations.

The land or real estate tax was by far the most important of the quatre vieilles, since it alone accounted for more than two-thirds of total receipts at the beginning of the nineteenth century and still for nearly half at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was in fact a tax on capital, except that only capital in the form of real estate was counted. Stocks, bonds, shares of partnerships, and other financial assets were excluded or, rather, were taxed only indirectly, to the extent that the associated businesses owned real estate, such as offices or warehouses, in which case they had to pay the corresponding contribution foncière. But in the case of industrial and financial firms whose principal assets were immaterial (such as patents, know-how, networks, reputation, organizational capacity, etc.) or in the form of foreign investments or other assets not covered by the real estate tax or other direct taxes (such as machinery and other equipment in theory subject to the patente but in practice taxed at well below their actual profitability), the capital in question was in actuality exempt from taxation or taxed at a very low rate. In the late eighteenth century such assets no doubt seemed relatively unimportant compared with real assets (such as houses, land, buildings, factories, and warehouses), but the fact is that they played an increasingly central role in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In any case, the important point is that the real estate tax, like the inheritance tax until 1901, was a strictly proportional tax on capital. In no way was the goal to redistribute property or reduce inequality; it was rather to tax property at a low and painless rate. In practice, the annual rate of taxation throughout the long nineteenth century was 3–4 percent of the rental value of the property, that is, less than 0.2 percent of the market value (since annual rents generally ran about 4–5 percent of a property’s market value).12

It is important to note that a tax on capital that is strictly proportional and assessed at such a low rate serves the owners of capital well. Indeed, during the French Revolution and throughout the period 1800–1914, capitalists saw this as the ideal tax system. By paying barely 0.2 percent a year on the value of capital and an additional 1 percent when “son succeeded father,” every capitalist obtained the right to enrich himself and accumulate ever more capital in peace, to derive the maximum profit from his property without having to declare the income or profits it generated, with the guarantee that any taxes due would not depend on the profits or rents actually realized. Because a low proportional tax on capital is not very intrusive and gives every advantage to the owners of capital, it has often been the preference of the wealthy. This was the case not only at the time of the French Revolution and throughout the nineteenth century but also throughout the twentieth century, and it continues to this day.13 In contrast, a tax on capital in the form of a truly progressive tax on wealth tends to frighten property owners, as we will see when we study the debates that erupted in the course of the twentieth century.

The real estate tax, which taxed capital at a low rate, was also the institutional tool with which political power was placed in the hands of property owners in the era of censitary monarchy (1815–1848). “Censitary” means that there was a property qualification for voting, which one met by paying above a certain amount in tax. During the Restoration, the right to vote was reserved to men over the age of 30 who paid at least 300 francs in direct taxes (which in practice granted eligibility to vote to about 100,000 people, or roughly 1 percent of adult males). In practice, since the contribution foncière accounted for the bulk of the receipts from the quatre vieilles, this meant as a first approximation that only the wealthiest 1 percent of real estate owners enjoyed the right to vote. In other words, the fiscal rules favored tranquil accumulation of capital while at the same allowing those who benefited from that system to formulate the political rules that ensured they would continue to do so. It would be difficult to imagine a clearer illustration of the inegalitarian proprietarian regime: the ownership society that flourished in France from 1815 to 1848 explicitly and openly relied on a property regime together with a political regime which guaranteed that that property regime would continue. In Chapter 5 we will see similar mechanisms at work in other European countries (such as the United Kingdom and Sweden).

Universal Suffrage, New Knowledge, War

After the revolution of 1848, in the brief interval of universal suffrage under the Second Republic, and then again with the advent of the Third Republic and the return of universal suffrage in 1871, debate on progressive taxation and the income tax resumed.14 In a context of rapid industrial and financial expansion, when it was plain to everyone that industrialists and bankers were reaping handsome profits while wages stagnated, plunging the new urban proletariat into misery, it seemed increasingly unthinkable that the new sources of wealth should not somehow be taxed. Although the idea of progressive taxation still frightened people, something had to be done. It was in this context that the law of June 28, 1872, was adopted, instituting a tax on income from securities (valeurs mobilières) known as the impôt sur le revenu des valeurs mobilières, or IRVM.

This tax was seen as a complement to the quatre vieilles, since it was levied on forms of income largely forgotten by the system of direct taxes established in 1790–1791. Indeed, for its time, the IRVM was a paragon of fiscal modernity, especially since its base was very large: it was levied not only on dividends from stocks and interest from bonds but also on “income of all kinds” that an owner of securities might receive in addition to any reimbursement of the capital invested, regardless of the precise legal category of the remuneration (including reserve distributions, bonuses, capital gains realized on the dissolution of a company, etc.). The data that emerged from the collection of the IRVM were also used to measure for the first time the rapid growth of this type of income between 1872 and 1914. What is more, the tax was collected at the source: in other words, it was paid directly by the issuer of the securities (banks, investment partnerships, insurance companies, and so on).

In terms of rates, however, the IRVM conformed to the pattern of the existing tax regime: the new tax was strictly proportional, with a single rate of 3 percent on income from all securities, from the tiny interest payments collected by a person who had purchased a few small bonds for his retirement to the enormous dividends, amounting to hundreds of years of the average man’s income, paid to wealthy stockholders with diversified portfolios. The rate was increased to 4 percent in 1890 and remained there until World War I. It would have been technically easy to raise rates quite a bit more and to make them progressive. But no government was prepared to assume the responsibility, so the IRVM ultimately had virtually no effect on the accumulation and perpetuation of large fortunes in the period 1872–1914.

Debate continued, and after many twists and turns the Chamber of Deputies in 1909 passed a law creating a general income tax (impôt général sur le revenu, or IGR). This was a progressive tax on all income (including wages, profits, rents, dividends, interest, and so on). In keeping with the bill filed in 1907 by the Radical Party’s minister of finance Joseph Caillaux, the system also included a package of so-called impôts cédulaires (levied separately on each cédule, or type of income). This was aimed at a larger number of individuals than the IGR, which was designed to tap only a minority of wealthy individuals, who were to be taxed progressively so as to achieve some degree of redistribution.

Caillaux’s bill was relatively modest, however: the rate on the highest incomes under the IGR was only 5 percent. Opponents nevertheless denounced it as an “infernal machine,” which, once set in motion, could never be stopped. This was the same argument that had been invoked against the inheritance tax, but it was advanced with even greater vehemence because the requirement for individuals to declare their income was considered intolerably intrusive. The Senate, which was as hostile to the progressive income tax as it had been to the progressive inheritance tax, refused to vote on the bill and blocked application of the new system until 1914. Caillaux and other proponents of the income tax used all the arguments at their disposal. In particular, they pointed out to those of their adversaries who predicted that top rates would quickly rise to astronomical levels that the rates of the progressive inheritance tax had actually changed relatively little since 1901–1902.15

Among the factors that played an important role in the evolution of ideas, it is particularly interesting to note that the publication of statistics derived from inheritance tax declarations, which began shortly after the creation of the progressive inheritance tax on February 25, 1901, helped to undermine the idea of an “egalitarian” France, which was often invoked by adversaries of progressive taxation. In parliamentary debates in 1907–1908, proponents of the income tax frequently alluded to this new knowledge to show that France was not the country of “smallholders” that their adversaries liked to describe. Joseph Caillaux himself read to the deputies from these statistics, and after showing that the number and size of very large estates declared in France every year had attained astronomical levels, he concluded: “We have been led to believe and to say that France was a country of small fortunes, of capital fragmented and dispersed ad infinitum. The statistics that the new inheritance regime has provided us force us to back away from that idea.… Gentlemen, I cannot hide from you the fact that these figures have forced me to modify in my own mind some of the preconceived ideas to which I alluded earlier, and have led me to certain reflections. The fact is that a very small number of individuals hold most of the country’s fortune.”16

Here we see how a major institutional innovation—in this case the introduction of a progressive inheritance tax—can lead, beyond its direct effect on inequality, to the production of new knowledge and categories, which in turn influence evolving political ideas and ideologies. Caillaux did not go so far as to calculate the share of different deciles and centiles in the annual estate figures of the time; the raw numbers spoke eloquently enough that everyone could see that France bore no resemblance to the “country of smallholders” described by the adversaries of progressivity. These arguments were not without influence on the chamber, which decided to make the inheritance tax more progressive in 1910, but they proved insufficient to persuade the Senate to accept a progressive income tax.

It is hard to say how much longer the Senate would have continued to resist had World War I not broken out, but there is no doubt that the international tensions of 1913–1914 and especially the new financial burdens created by the law mandating three years of military service and the “imperatives of national defense” played a decisive role in eliminating the roadblock and probably a greater role than the good results achieved by the Radicals and Socialists in the May 1914 elections. The debate took many turns, the most spectacular of which was no doubt the Calmette affair.17 In any case, the Senate agreed at the last minute to include the IGR passed by the Chamber of Deputies in 1909 in an emergency finance bill that was adopted on July 15, 1914, two weeks after the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo and a little more than two weeks before the declaration of war. In exchange, the senators obtained a further reduction in the progressivity of the tax (the top rate was reduced from 5 to 2 percent).18 This was the progressive income tax that was applied for the first time in France in 1915, in the midst of war, and that has continued to be applied ever since, not without numerous reforms and revisions. As with the inheritance tax, it was not until the interwar years that the top rates attained modern levels (several tens of percent).

To sum up, from the French Revolution to World War I, the French tax system offered ideal conditions for the accumulation and concentration of wealth, with tax rates on the highest incomes and largest fortunes that were never more than a few percent—hence purely symbolic, without real impact on the conditions of accumulation and transmission. Thanks to new political coalitions and deep changes in political thinking and ideologies, a new tax system began to be put in place before the war, most notably with the adoption of a progressive inheritance tax in 1901. The full effects of this new system were not felt until the interwar years, however, and even more under the new social, fiscal, and political pact that was achieved in 1945, at the end of World War II.

The Revolution, France, and Equality

Ever since the Revolution of 1789, France has presented itself to the world as the land of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The promise of equality at the heart of this great national narrative does have some tangible support, such as the abolition of the fiscal privileges of the nobility and clergy on the Night of August 4, 1789, as well as the attempt to establish a republican regime based on universal suffrage in 1792–1794, a bold undertaking for the time. All this took place in a country with a much larger population than other Western monarchies. Indeed, the constitution of a central government capable of ending seigneurial jurisdictional privileges and working toward greater equality was no mean achievement.

As for achieving real equality, however, the great promise of the Revolution went unfulfilled. The fact that the concentration of ownership steadily increased throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, so that it stood higher on the eve of World War I than at the time of the Revolution, shows how wide the gap was between the promise of the Revolution and the reality. And when a progressive income tax was finally adopted on July 15, 1914, it was not to finance schools or public services but to pay for war with Germany.

It is particularly striking to note that France, the self-proclaimed land of equality, was actually one of the last of the wealthy countries to adopt a progressive income tax. Denmark did so in 1870, Japan in 1887, Prussia in 1891, Sweden in 1903, the United Kingdom in 1909, and the United States in 1913.19 To be sure, it was only a few years before the war that this emblematic fiscal reform was adopted in the United States and United Kingdom, and in both cases it came only after epic political battles and major constitutional reforms. But at least these were peacetime reforms intended to finance civil expenditures and reduce inequality rather than responses to nationalist and military pressures as in France’s case. No doubt the income tax would have been adopted in the absence of the war, to judge by the experience of other countries; or it might have come in response to other financial or military crises. Yet the fact remains that France was the last country in the list to adopt a progressive income tax.

It is also important to note that the reason why France lagged behind other countries and displayed such hypocrisy about equality had a great deal to do with its intellectual nationalism and historical self-satisfaction. From 1871 to 1914, the political and economic elites of the Third Republic used and abused the argument that the Revolution had made France an egalitarian country so that it had no need for confiscatory, inquisitorial taxes, unlike its aristocratic and authoritarian neighbors (starting with the United Kingdom and Germany, which were well advised to adopt progressive taxes in order to have a chance to come closer to the French egalitarian ideal). Unfortunately, this French egalitarian exceptionalism had no basis in fact. The inheritance archives show that nineteenth-century France was hugely inegalitarian and that concentration of wealth continued to increase right up to the eve of World War I. Joseph Caillaux invoked these very statistics in a debate in 1907–1908, but the prejudices and interests of senators were so strong that Senate approval proved impossible to obtain in the ideological and political climate of the time.

Third Republic elites did cite potentially relevant comparisons, such as the fact that land ownership was considerably more fragmented in France than in the United Kingdom (in part because the Revolution had redistributed land to a limited degree but mostly because land holdings were exceptionally concentrated on the other side of the English Channel). They also noted that the Code Civil (1804) had introduced the principle of equal partition of estates among siblings. Equipartition, which in practice applied only to brothers (because sisters, once married, forfeited most of their rights to their husbands under the highly patriarchal proprietarian regime in force in the nineteenth century) was attacked throughout the nineteenth century by counterrevolutionary and anti-egalitarian thinkers, who held it responsible for harmful fragmentation of parcels and above all for fathers’ loss of authority over their sons, who could no longer be disinherited.20 In fact, the legal, fiscal, and monetary regime in force until 1914 strongly favored extreme concentration of wealth, and this played a far more important role than the equipartition of estates among brothers instituted by the Revolution.

Reading about these episodes today, at some distance from the Belle Époque, one is struck by the hypocrisy of much of the French elite, including many economists, who did not hesitate to deny against all evidence that inequality posed any problem whatsoever.21 One can of course read this as a sign of panic that a harmful wave of redistribution might be unleashed. At the time, no one had any direct experience with large-scale progressive taxation, so it was not unreasonable to think that it might threaten the country’s prosperity. Still, reading about these exaggerated warnings should put us on our guard against such wildly pessimistic counsel in the future.

As we will see, such short-sighted use of grand national narratives is unfortunately quite common in the history of inegalitarian regimes. In France, the myth of the country’s egalitarian exceptionalism and moral superiority has often served to disguise self-interest and national failure, whether as an excuse for colonial rule in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries or for the glaring inequalities in the French educational system today. We will find similar intellectual nationalism in the United States, where the ideology of American exceptionalism has often served as a cover for the country’s inequalities and plutocratic excesses, especially in the period 1990–2020. It is equally plausible that a similar form of historical self-satisfaction will develop soon in China, if it hasn’t done so already. Before turning to these matters, we need to continue our study of the transformation of European societies of orders into ownership societies to gain a better understanding of the many possible trajectories and switch points.

Capitalism: A Proprietarianism for the Industrial Age

Before continuing, I also want to clarify the connection between proprietarianism and capitalism as I see it for the purposes of this study. In this book I have chosen to stress the ideas of proprietarian ideology and the ownership society. I propose to think of capitalism as the particular form that proprietarianism assumed in the era of heavy industry and international financial investment, that is, primarily in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Generally speaking, whether we are talking about the capitalism of the first industrial and financial globalization (in the Belle Époque, 1880–1914) or the globalized digital hypercapitalism that began around 1990 and continues to this day, capitalism can be seen as a historical movement that seeks constantly to expand the limits of private property and asset accumulation beyond traditional forms of ownership and existing state boundaries. It is a movement that depends on advances in transport and communication, which enable it to increase global trade, output, and accumulation. At a still more fundamental level, it depends on the development of an increasingly sophisticated and globalized legal system, which “codifies” different forms of material and immaterial property so as to protect ownership claims as long as possible while concealing its activities from those who might wish to challenge those claims (starting with people who own nothing) as well as from states and national courts.22

In this respect, capitalism is closely related to proprietarianism, which I define in this study as a political ideology whose fundamental purpose is to provide absolute protection to private property (conceived as a universal right, open to everyone regardless of old status inequalities). The classic capitalism of the Belle Époque is an outgrowth of the proprietarianism of the age of heavy industry and international finance, just as today’s hypercapitalism is an outgrowth of the era of the digital revolution and tax havens. In both cases, new forms of holding and protecting property were put in place to protect and extend accumulated wealth. There is nevertheless a benefit to distinguishing between proprietarianism and capitalism, because the proprietarian ideology developed in the eighteenth century, well before heavy industry and international finance. It emerged in societies that were still largely preindustrial as a way of transcending the logic of trifunctionalism in a context of new possibilities offered by the formation of a centralized state with a new capacity to discharge regalian functions and protect property rights in general.

As an ideology, proprietarianism might in theory be applied in primarily rural communities with relatively strict and traditional forms of property holding, in order to preserve them. In practice, the logic of accumulation tends to drive proprietarianism to extend the frontiers and forms of property to the maximum possible extent, unless other ideologies or institutions intervene to establish limits. In the case that concerns us here, the capitalism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries coincided with a hardening of proprietarianism in the era of heavy industry that witnessed growing tensions between stockholders on the one hand and the new urban proletariat, concentrated in huge production units and united against capital, on the other.

This hardening was reflected, moreover, in the nineteenth-century novel’s depiction of property relations. The ownership society of 1810–1830 that Balzac describes is a world in which property has become a universal equivalent, yielding reliable annual incomes and structuring the social order; yet direct confrontation with those who work to produce those incomes is largely absent. The Balzacian universe is profoundly proprietarian, as is that of Jane Austen, whose novels are set in England in the period 1790–1810. In both cases we are a long way from the world of heavy industry.

In contrast, when Émile Zola published Germinal in 1885, social tensions in the mining and industrial regions of northern France were at an all-time high. When the workers exhaust the meager funds they have collected to support their very bitter strike against the Compagnie des Mines, the grocer Maigrat refuses to extend credit. He ends up emasculated by the town’s women, who, disgusted by the sexual favors this vile agent of capital has so long demanded of them and their daughters, are exhausted and out for blood after weeks of struggle. What is left of his body is publicly exposed and dragged through the streets. We are a long way from Balzac’s Paris salons and Jane Austen’s elegant balls. Proprietarianism has become capitalism; the end is near.

1. The Paris work was conducted by G. Postel-Vinay and J.-L. Rosenthal. The départemental work was organized primarily by J. Bourdieu, L. Kesztenbaum, and A. Suwa-Eisenman. See esp. T. Piketty, G. Postel-Vinay, and J. L. Rosenthal, “Wealth Concentration in a Developing Economy: Paris and France, 1807–1994,” American Economic Review, 2006. See online appendix for a full bibliography.

2. See B. Garbinti, J. Goupille-Lebret, and T. Piketty, “Accounting for Wealth Inequality Dynamics: Methods and Estimates for France (1800–2014),” WID.world, 2017. In Part Three I will return to the current structure of wealth inequality. See esp. Chap. 11, Fig. 11.17.

3. Between 1800 and 1914, average wealth at death was multiplied by more than six in Paris (from 20,000 to roughly 130,000 francs, counting those who died with nothing) and by nearly five in all of France (from 5,000 to 25,000 francs). This increase was real, not just nominal, because the purchasing power of the franc did not very much in this period. See T. Piketty, G. Postel-Vinay, and J.-L. Rosenthal, “Wealth Concentration in a Developing Economy: Paris and France, 1807–1994.” See also J. Bourdieu, G. Postel-Vinay, and A. Suwa-Eisenmann, “Pourquoi la richesse ne s’est-elle pas diffusée avec la croissance? Le degré zéro de l’inégalité en France et son évolution en France 1800–1940,” Histoire et mesure, 2003.

4. The graphs in Figs. 4.1 and 4.2 reflect inequality of wealth among living adults at each date. We started with wealth at time of death and then reweighted each observation according to the number of living individuals in each age cohort, taking into account different mortality rates at different levels of wealth. In practice, this did not make much difference. Concentration of wealth among the living is barely a few percentage points greater than inequality of wealth at death, and all temporal evolutions are more or less the same. See the online appendix.

5. On Vautrin’s lesson, see T. Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. A. Goldhammer (Harvard University Press, 2014), pp. 228–232.

6. Note that the percentage of Paris real estate is highest in the 90th–99th percentiles and drops in the 50th–90th percentiles. This is because the latter group was far too poor to own Paris real estate, and their real estate holdings consisted mainly of provincial (and especially rural) properties. Note, too, that I did not include debts in Table 4.1 (on average barely 2 percent of gross assets in 1872 and 5 percent in 1912). See the online appendix for complete results.

7. On the evolution of inheritance tax law over the long nineteenth century, see T. Piketty, Top Incomes in France in the Twentieth Century, trans. S. Ackerman (Harvard University Press, 2018), pp. 301–304, 991–1012.

8. See Impressions parlementaires, vol. 4, no. 482. On these debates see also A. Daumard, Les fortunes françaises au 19e siècle. Enquête sur la répartition et la composition des capitaux privés d’après l’enregistrement des déclarations de successions (Mouton, 1973), pp. 15–23.

9. On the quatre vieilles and the transition to an income tax, see Piketty, Top Incomes in France, pp. 234–242. See also C. Allix and M. Lecerclé, L’impôt sur le revenu (impôts cédulaires et impôt général). Traité théorique et pratique (1926).

10. The monarchy had attempted to introduce limited forms of fiscal progressivity in the eighteenth century, especially in the form of the taille tarifée, which distinguished several classes of taxpayer on the basis of the approximate level of their resources while maintaining exemptions for the nobility and the clergy in other parts of the tax system, which was hardly consistent. In some ways, the Revolution simplified things by imposing proportionality for everyone on an indicial basis and eliminating any direct reference to income. On the taille tarifée, see M. Touzery, L’invention de l’impôt sur le revenu. La taille tarifée (1715–1789) (CHEFF, 1994).

11. The contribution personnelle-mobilière was no doubt the most complex of the quatre vieilles, since it initially included not just the tax based on the rental value of the principal residence, which was its main component, but also a tax on servants, a tax equal to the value of three days of work, and a tax on horses, mules, etc. This was the tax that Condorcet proposed to reform in 1792 by introducing a schedule of progressive rates on rental values as a correction to the tax’s inherent regressivity. The residential tax, the direct descendant of this tax, is to be gradually eliminated between 2017 and 2019, and it is not yet known what local tax will replace it.

12. In other words, a property valued at 1,000 francs produced a rent on the order of 50 francs per year (5 percent of 1,000 francs), which called for a payment of just 2 francs in taxes (4 percent of 50 francs), equivalent to a rate of 0.2 percent on the capital of 1,000 francs. See Piketty, Top Incomes in France, pp. 238–239.

13. For example, it was in this spirit, and in the name of economic efficiency, that Maurice Allais proposed in the 1970s to eliminate the income tax and replace it with a low-rate tax on real capital, very similar in principle to the contribution foncière. See M. Allais, L’impôt sur le capital et la réforme monétaire (Hermann, 1977).

14. The Second Republic (1848–1852) ended when the Second Empire was proclaimed by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who had been elected president by universal suffrage in December 1848. His uncle Napoleon had ended the First Republic (1792–1804) when he, too, decided to have himself crowned as emperor.

15. In the Chamber of Deputies on January 20, 1908, Caillaux put this argument clearly: “Since we have had a progressive tax on the books for six years with a change of rates, do not tell us that a progressive system must necessarily lead in a short period of time to higher rates.” See J. Caillaux, L’impôt sur le revenu (Berger-Levrault, 1910), p. 115.

16. Caillaux, L’impôt sur le revenu, pp. 530–532.

17. Named for the editor of Le Figaro, who was murdered in his office on March 16, 1914, by Joseph Caillaux’s wife in the wake of the newspaper’s unremitting attacks on her husband, climaxing with the publication on March 13, 1914, of a letter from Caillaux to his mistress. The letter, signed “Ton Jo,” had been written in 1901, following the failure of the first Caillaux bill, of which Caillaux wrote that he had “crushed the income tax while appearing to defend it.” This letter was supposed to show that the promoters of the income tax were only opportunists who were using the wretched bill solely to advance their political careers.

18. The law of July 15, 1914, instituting the IGR was completed by the law of July 31, 1917, which created the impôts cédulaires envisioned in the Caillaux reform. For details, see Piketty, Top Incomes in France, pp. 246–262.

19. In the United Kingdom a separate proportional tax on each of several categories of income (interest, rent, profits, wages, etc.) was established in 1842, but it was not until 1909 that a progressive tax on total income was adopted.

20. Under the “available quota” (quotité disponible) system instituted in 1804 and still in force today, parents could freely dispose of half their property if they had one child (the other half went automatically to the child, even if all relations had been broken off); this fell to one-third if they had two children (with equal division of the remaining two-thirds between the siblings); and one-quarter if they had three or more children (with equipartition of the remaining three-quarters). Denunciation of the supposedly harmful effects of this system was a major conservative and counterrevolutionary theme in the nineteenth century, especially in the work of Frédéric Le Play. This criticism largely disappeared in the twentieth century.

21. Take Paul Leroy-Beaulieu, one of the most influential liberal economists of his time as well as an enthusiastic spokesman for colonization, and his famous Essai sur la répartition des richesses et sur la tendance à une moindre inégalité des conditions, published in 1881 and regularly reprinted for the next thirty years. Although all the available statistical sources suggested the opposite, he defended the idea that the tendency is for inequality to fall, even if he had to invent implausible arguments to do so. For instance, he noted with satisfaction that the number of indigents needing assistance grew by 40 percent in France between 1837 and 1860, even as the number of charity offices almost doubled. One had to be very optimistic indeed to deduce from these figures that the actual number of indigents had fallen (which he did without hesitation), but beyond that, even a decrease in the absolute number of poor in a growth context would obviously tell us nothing about the size or evolution of the gap between rich and poor. See Piketty, Top Incomes in France, pp. 522–531.

22. See Pistor, The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality (Princeton University Press, 2019).