CHAPTER 16

Etruscan Textiles in Context

Margarita Gleba

1. Introduction

Textiles represent a category of archaeological material little known to the general archaeological audience. Although textiles were recovered already in the first archaeological excavations and many of the pioneering publications date to the early twentieth century, only recently have they begun to be studied extensively as a part of the cultural record. Over the last few decades, textile studies have developed into an important new field of archaeology (Good 2001; Andersson Strand et al. 2010). The accumulation of data and the constant development of analytical techniques now permit more precise fiber and dye identifications. Meanwhile, the proliferation of technical studies finally allows a more synthetic approach to the history of textile technology. These not only demonstrate how much can be learned about the culture, society, technology, and economy of the ancient world through textiles but they also allow scholars to place them in their original context (Barber 1991; Gleba and Mannering 2012).

Because the environmental conditions in the Apennine peninsula are generally not conducive to the survival of organic material, the study of ancient textiles produced in this region has progressed more slowly in comparison to the situation in central and northern Europe. Etruscan textiles have been studied primarily through indirect evidence, with iconographic material being the most frequently cited source of information. Thus, Etruscan clothing, which is depicted on figurines, statues, and vases as well as in tomb paintings, has been studied extensively by Larissa Bonfante (2003). Meanwhile, various technical and social aspects of textile production in Etruria have been gleaned through a few important iconographic monuments. For example, the wooden cylindrical throne found in Tomb 89 at Verucchio, dated to c.700 BCE (see also Chapter 21), contains a scene related to textile production. While interpretations of the intricately carved images vary (Torelli 1997: 68–69; von Eles 2002), most scholars agree that spinning and weaving are among the depicted activities. Another important object is a bronze rattle or tintinnabulum found in Tomb 5 of the Arsenale Militare necropolis in Bologna, dated to around 600 BCE (Morigi Govi 1971; also Chapter 21). Each side of the tintinnabulum, which is decorated in the repoussé technique, is divided into two sections; four scenes of various stages of textile manufacture are depicted. The bottom scene on Side A depicts two women seated in throne-like chairs at the task of dressing distaffs with fiber. Above them, a woman spins with a drop-spindle. Side B of the tintinnabulum shows the weaving of the starting border necessary for the warp-weighted loom at the bottom, while the top scene provides a rendering of an unusual two-storied warp-weighted loom.

Scientific publications of actual Etruscan textiles started to appear only in the 1970s, and investigation of textile tools and textile production is an even more recent phenomenon. The catalogue of published, archaeologically excavated textiles has grown steadily since the publication of Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy (Gleba 2008) as has the study of textiles tools and their various contexts.

2. The Material Remains of Textiles and Textile Implements in Etruria

Etruscan textiles survive in either an original organic, charred or, most frequently, mineralized state. The largest groups of textile remains still in their organic state of preservation have been excavated at Verucchio (Stauffer 2002, 2003, 2004, 2012) and at Sasso di Furbara (Masurel 1982; Mamez and Masurel 1992). Other finds come from Casale Marittimo (Esposito 1999), Volterra (Fiumi 1976: 65) and Cogion-Coste di Manone (Gleba and Turfa 2007). Probably the most famous Etruscan textile is the Liber linteus, the linen book of Zagreb which survived thanks to its reuse as mummy wrappings in Egypt (Roncalli 1980; Flury-Lemberg 1988; van der Meer 2007; and Chapter 14 in this volume). The vast majority of archaeological textiles recovered in Etruria survive as mineralized traces on metal grave goods, such as bronze and iron weapons, personal accessories, and vessels. Mineralized textiles are formations in which metal corrosion products form casts around fibers retaining their external morphology and size almost unaltered either as positive or negative casts (Chen et al. 1998). Numerous textiles preserved in association with metal objects have been found in the burials of Bologna, Chiusi, Chianciano, Veii, Vulci, Tarquinia, Casale Marittimo, Murlo, and many other Etruscan sites (see catalogue in Gleba 2008: 50–56). In the past they were frequently removed as part of the conservation process, but more attention is being paid to these textile traces at present. Even when minute, they can provide a considerable amount of information about ancient textiles (see e.g., Bender Jørgensen 1986; 1992). Thus, when traces of different weave types are found on the same fibula, as for instance in some of the finds from Tarquinia Le Rose (Buranelli 1983: 129), a conjecture can be made that the deceased was wearing several layers of garments. If a number of textile traces are present in a burial, their distribution, position, and the direction of the weave in each fragment can help scholars reconstruct where the garments were located.

Even when textiles do not survive, their original presence may be indicated through other evidence, such as the location of fibulae and other decorative ornaments. In some cases, reconstructions of garments are possible based on the position of surviving decorative elements in relation to the skeleton, sarcophagus, or trench, as in the case of some female costumes for the burials at Verucchio (Bentini and Boiardi 2007: 135 figs. 13–14). Thus, a shroud with a border consisting of small bronze rings has also been hypothesised for an Early Iron Age female inhumation in Tarquinia (Trucco 2006: 100). Meanwhile, the discovery of various small decorative objects such as beads and fibulae on the outside of the top part of the cinerary urn likely indicates that the urn was wrapped with a cloth, which was decorated or fastened with them. Such, for example, is the case of several ninth century BCE cinerary urns at Tarquinia (Trucco 2006: 98–99).

Investigation of the surviving textiles has demonstrated that the inhabitants of Etruria utilized sophisticated technologies for textile production and that they were familiar with diverse fibers, dyes, and weaving techniques (Gleba 2008). Thus, a variety of fibers were used in textile production in ancient Italy. These include linen, hemp, esparto, various tree basts, sheep wool, goat hair and even mineral asbestos. This variety reflects not only the availability of raw materials – whether locally available or obtained through exchange – but also the knowledge of technologies to convert them from their raw state to usable fiber. Numerous techniques were used to create textiles, including loom weaving, tablet weaving, soumak, and a form of twining. The thread counts go up to 30–40 threads per centimeter, which reflects their quality. Already during the ninth century BCE, there is a clear tendency to combine yarns of opposite twists to create spin-patterned textiles. Examples such as those discovered in Verucchio and Sasso di Furbara indicate both the Etruscans’ knowledge of this technique and their appreciation of the subtlety of spin patterns.

Dyeing techniques appear in Italy from at least the Early Iron Age. Recent dye analyses of surviving textiles demonstrate the popularity of reds, blues, and purples. Thus, Verucchio Mantle 1 was dyed red with madder, while the fibers of its border were most likely treated with madder and woad, resulting in a purple hue (Stauffer 2012). Mantle 2, on the other hand, was dyed red-orange with madder and a yellow dye, while its border was also dyed with woad, creating a purple-red effect. Dye analyses thus demonstrate that several different dyes were used to add color to the Verucchio textiles, while their combination in some textiles shows an understanding of a complex, multiple-stage dyeing processes. The most expensive dye of antiquity – royal or shellfish purple – has recently been identified in textiles from the Hellenistic period burials at Strozzacapponi (Perugia) (Gleba and Vanden Berghe 2014).

In the absence of extant textiles, studies of the number, distribution, and morphology of textile tools – based on statistical analyses of their physical parameters of preservation, size, weight, and use wear – can provide valuable information about technology, scale of production, and the importance of textile manufacture for a particular site. Functional typologies of tools, combined with analysis of the contexts in which they were found and their distribution patterns, allow inferences about changes and development of textile production in and between different sites and regions. This makes it possible to address issues such as the spread and use of technology, the mobility of craftspeople, communication patterns, and chronological changes in production.

3. Case Study: Poggio Civitate and Poggio Aguzzo (Murlo)

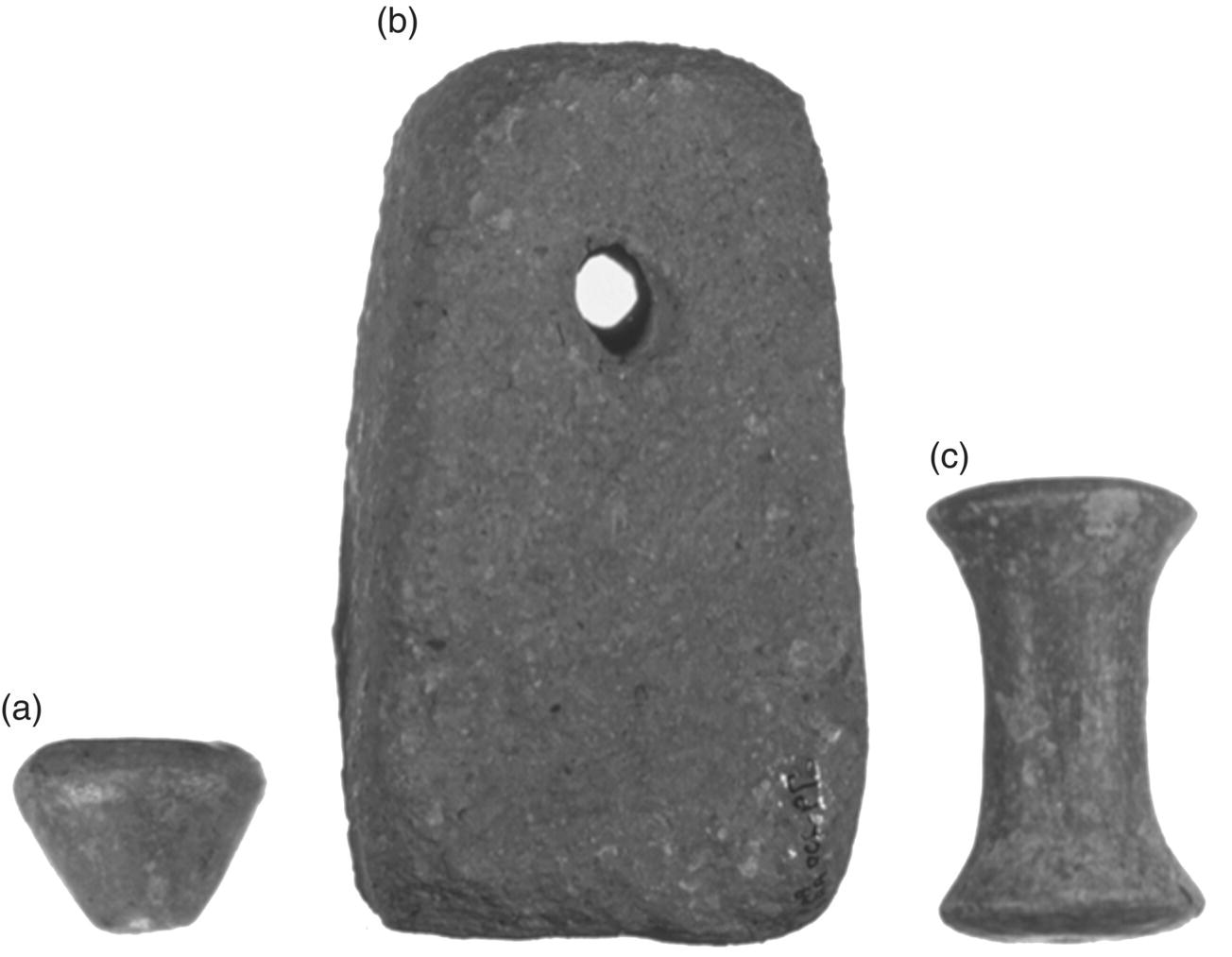

The site of Poggio Civitate (Murlo), located 25 kilometers south of Siena thrived between the early seventh and third quarter of the sixth centuries BCE (see further, Chapter 8 in this volume), and furnishes excellent material for a case study. The information that can be retrieved from analyses of the textile implements found throughout the site (Figure 16.1) can be compared to the technical data gained from the study of textile fragments found in the contemporary burials at the nearby Poggio Aguzzo (Figure 16.2). Judged solely by the number of spinning and weaving implements found, Poggio Civitate appears to have been a significant textile-producing center. In 1998, the catalogued and analyzed finds included 441 spindle whorls, 69 loom weights, 580 spools and 13 needles. The latest catalogue lists 568 spindle whorls, 94 loom weights, 849 spools (rocchetti), and 15 needles (see the Poggio Civitate Archaeological Archive database (http://www.poggiocivitate.org/) for the most up-to-date counts and additional information about the site’s finds; last accessed July 31, 2015).

Figure 16.1 Textile tools from Poggio Civitate, Murlo: a) spindle whorl; b) loom weight; c) spool.

Photo: Courtesy of the Poggio Civitate Archaeological Excavations.

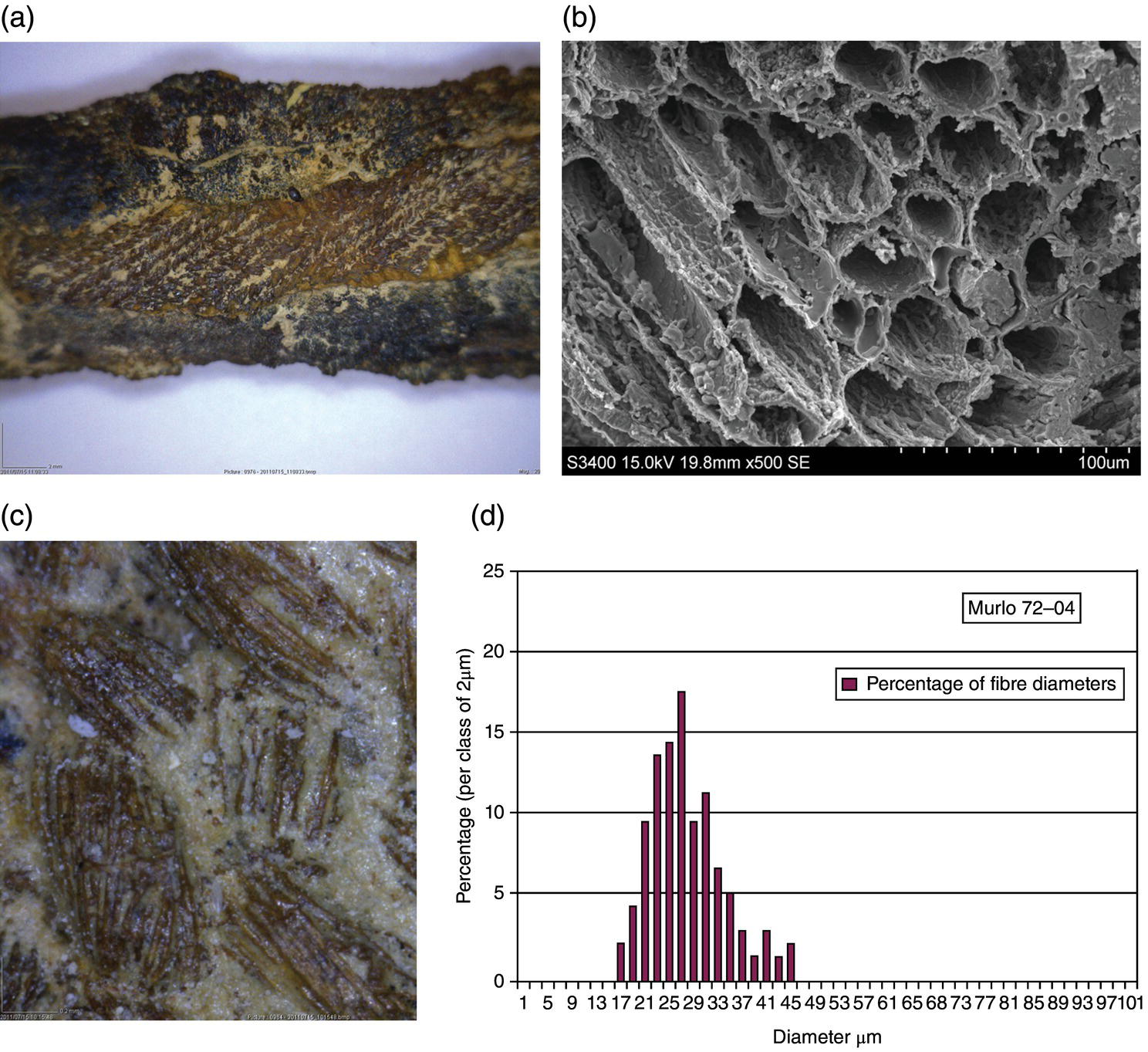

Figure 16.2 Textiles from Poggio Aguzzo, Murlo: a) tablet weave on an iron spear counterweight; b) Scanning Electron Microscope image of the negative casts of wool fibers of textile from Tomb 1; c) tabby textile preserved on the iron knife from Tomb 4 under high magnification with twist of the yarn and fibers clearly visible; d) histogram of wool quality measurements of textile from Tomb 1.

Photo: M. Gleba.

The great number of spindle whorls at Poggio Civitate, especially when compared to other contemporaneous sites for which similar information is available (e.g., Acquarossa and Lago d’Accesa), indicates that the scale of yarn production was large, well beyond the requirements of domestic needs. The mean weight of spindle whorls at Poggio Civitate is around 10 grams (range 2–48), which is appropriate for spinning short, fine fiber. This suggests that a large quantity of very fine yarn was produced at the site. Over 90 percent of the whorls are of a truncated conical shape, suitable for spinning yarn of medium twist. The very uniform proportions of the whorls also suggest that spinning was both organized and specialized. The concentration of the large number of very uniform implements in specific areas of the site, such as the so-called Southeast Building (also known as OC2/Workshop), suggests that spinning was one of the major crafts on the site.

The number of loom weights at Poggio Civitate seems to be small in comparison to the numbers of spindle whorls and spools. Their weight ranges from 34 to 795 grams. This is a very broad range in comparison to loom weight size at contemporary sites, which suggests that textiles of various qualities and complexities were produced at Poggio Civitate.

Although not all parts of the site have been excavated, the numbers of spindle whorls with respect to loom weights suggest that the amount of yarn spun significantly exceeded the quantity of fabric that was being produced at the site. This inconsistency may be explained by the extraordinary quantity of spools discovered on the site. Their number (over 840) is higher even than the quantity of spindle whorls and, if the hypothesis that they were used in tablet weaving is correct (see Raeder Knudsen 2012), it may indicate that the weaving workshop at Poggio Civitate specialized in the production of patterned tablet-woven bands, which could have been used to decorate garments and other textiles. This interpretation is suggested by the popularity of patterned borders on garments depicted in contemporary figurative representations (Bonfante 2003) and by the survival of actual borders found at Verucchio (Stauffer 2002), Sasso di Furbara (Mamez and Masurel 1992) and Poggio Aguzzo (see below). Such a situation would not be surprising, especially since, in addition to being decorative, these elements were also indicators of status (Stauffer 2012).

Finally, a number of needles have been found at Poggio Civitate. Not only do they indicate that sewing was practiced on the site, but they also suggest that several workers could have been sewing simultaneously, because in normal domestic contexts, needles are quite rare.

The distribution and style of decoration of the spinning and weaving implements at Poggio Civitate may be taken to indicate that most of them were probably associated with the Orientalizing phase, and hence, were manufactured and/or used over the period of about a quarter to a half of a century. Although scattered by the destruction and levelling of the site, the tools for textile production appear to be concentrated in two areas, both associated with structures dating to the late seventh century BCE. One is in the northern part of the Lower Building (also known as OC1/Residence) (see Figure 8.1). Another area in which implements are concentrated is around, and to the north of, the so-called Southeast Building (or OC2/Workshop) (see also Figure 8.1). This structure has been identified as an industrial center because of deposits of the debris of ivory, glass and bronze working, as well as the presence of unfired tiles (Nielsen 1998: 98–99). The distribution of spinning and weaving implements not only confirms the functional identification of this structure but also suggests that textile manufacture was as important as the production of other types of materials and goods, mostly luxury in nature.

From this brief summary it is clear that textiles were manufactured at Poggio Civitate on a scale significantly greater than what would be considered production for domestic consumption. In fact, the evidence of textile implements points towards Poggio Civitate having played an important role in the production and possibly even textile exchange during the Orientalizing period. Analysis of textile tools thus permits scholars to draw some conclusions about the role textiles played in the economy of an important settlement in inland Etruria.

In the meantime, recently analyzed mineralized textiles from the burials at the nearby Poggio Aguzzo, provide a more tangible idea of what these textiles may have looked like, what material they were made of and how they were used (see Figure 16.2). Textile traces survive on two iron spear counterweights from Tomb 1 and an iron knife from Tomb 4, all dated to the seventh century BCE, and hence contemporary with the majority of the textile tools recovered from Poggio Civitate (Tuck 2009). The knife blade preserves textile traces on both surfaces and going over the edges, indicating that it was deliberately wrapped in the textile. Wrapping metal grave goods is a common phenomenon in Etruria and pre-Roman Italy in general. Knives, weapons, strigils, spits, and mirrors are among the most common objects to have been wrapped (Gleba 2014). The deposition of such “enclothed” objects in funerary containers, in certain cases, excludes the possibility of accidental contact with textiles. It is unclear, however, whether this phenomenon has a ritual significance in the funerary environment or if it represents a regular practice tied to the safekeeping of precious metal objects. The textile weave appears to be a relatively balanced tabby woven in single-spun z-twisted yarn. The yarn measures ca. 0.4–0.5 millimeters in diameter in both systems. This quality of yarn corresponds well with the mean weight of the spindle whorls at Poggio Civitate, as light whorls (10–25 grams) are optimal for spinning yarn with diameters 0.3–0.6 millimeters (Grömer 2005). The thread count is about 18–20 threads/cm in both weave systems. Fibers (most likely sheep wool) appear quite uniform in terms of diameter under high magnification, and are positioned quite parallel to each other, suggesting that the wool may have been combed prior to spinning.

Likewise, one of the iron spear counterweights from Tomb 1 preserves textile traces in various areas on its surface, but it is unclear whether the textile was deliberately wrapped around the object or if it came in contact with it incidentally. The textile weave appears to be a twill. The thread measures about 0.4 millimeters in both systems and is single-spun, medium z-twisted. The thread count in both systems is about 20 threads per centimeter. Thus, in this case, the technical parameters of the textile also correspond well to those of the textile tools found at Poggio Civitate.

The second iron spear counterweight from Tomb 1 preserves clear traces of a tablet weave and possible traces of another textile. Here, too, it is unclear whether the textile was wrapped deliberately around the object or if it came in contact with it by accident. However, the fact that the preserved traces are of a tablet weave (and they only appear on one side of the object) suggest the latter, as tablet weaves are usually found on items of clothing and generally garments of special and/or ceremonial nature (see Chapter 21). It is also possible that a garment of the deceased may have been positioned in the burial in such a way that it covered the spear counterweight.

Tablet weaving involves passing threads through holes in the corners of (usually) square tablets which, when rotated forward or back, force the threads to form different sheds. By rotating cards in different combinations, it is possible to achieve numerous and quite complex patterns. This method is suitable for weaving narrow bands (such as for belts), heading bands for the warp of a warp-weighted loom, or decorative borders for the ground textile weave. Tablet weaving in Etruria is attested not only by the presence of such borders on textiles (e.g., the examples from Verucchio; cf. Raeder Knudsen 2012), but also by the finds of tablets, metal clasps, bone spacers with pegs and, particularly, terracotta spools. The latter were probably used as weights in tablet weaving. As noted above, extraordinarily large quantities of spools have been found at Poggio Civitate, documenting intensive tablet weaving activity at the site during the Orientalizing period.

The tablet weave on the second spear counterweight from Tomb 1 at Poggio Aguzzo is made up of at least 17 tablets alternating the direction of the tablet rotation in a pattern 3Z3S, with about 12 tablets per centimeter. The threads are single spun z-twisted and measure about 0.3 millimeters in diameter. The subtle pattern created by alternating S and Z direction of tablet rotation (which could have been enhanced by dyeing the alternating groups of threads different colors) would have been visible as stripes. This kind of pattern appears on some of the tablet borders found at Verucchio (Raeder Knudsen 2012). It is impossible to know how wide the tablet weave originally was or if it incorporated any other pattern, but a conjecture may be made that it was a border of a garment, traces of which are no longer clearly discernible on the spear counterweight. Some single threads seen on its surface are s-twisted, unlike the tablet weave yarn. Yet another area preserves what appears to be a textile with extremely tangled fibres on the surface and no discernible weave structure – indication of either hard wear or fulling of the surface. In either case, the textile would likely have been an item of outerwear.

Overall, the textiles from Poggio Aguzzo fit well within the corpus of Etruscan textiles studied thus far. They are typical in terms of their weave (tabby and twill are among the most common weaves during the seventh century BCE), twist direction (while many Etruscan textiles are spin patterned, the majority are woven in z-twisted yarn), and thread count (see Table 2b in Gleba 2008: 85). Tablet weaves are also not unusual and appear to be markers of status and ceremonial textiles in burials.

In addition to the technical aspects of the original textiles, mineralized traces also allow identifying their raw material. Using Scanning Electron Microscopy, the raw material of the textiles from Tomb 1 at Poggio Aguzzo was identified as sheep wool, based on the characteristic scales preserved as negative impressions on the metal salts. Measuring the diameter of the voids left by the fibers also permitted wool quality analysis. The quality of modern wool is determined by its fiber diameter, crimp, yield, color, and staple strength and length. Fiber diameter is the single most important wool characteristic determining quality and price. Analyses of wool fiber fineness have been used to determine the fleece type of prehistoric sheep, enabling comparisons with fleeces from modern sheep, particularly the so-called primitive or unimproved sheep breeds, and leading to conclusions about ancient breeds. A fleece consists of the outer coat containing coarse kemp (over 100 microns in diameter) and hair (over 60 microns in diameter), and the much finer underwool. Assessment of fiber quality is based on a technique used in the modern textile industry and consists of the diameter measurement of 100 fibers per thread or staple, and statistical analyses resulting in a distribution histogram.

The wool in the Poggio Aguzzo textiles has a rather wide distribution curve, generally skewed to fine, with the maximum diameter not exceeding 50 microns and with a mean diameter and mode above 20 microns. This type of wool appeared in Europe at least by the seventh century BCE. Similar distributions are found in wool samples from other contemporaneous and later Italian sites, such as Riesenferner, Este, Belmonte (Gleba 2012) and Monte Bibele (Moulhérat 2008), as well as from Greece (Metallinou et al. 2009), Switzerland (Rast-Eicher 2008) and Austria (Rast-Eicher and Bender Jørgensen 2013).

Detailed analysis of the textile fragments from Poggio Aguzzo therefore demonstrates the quantity and quality of the information which can be gleaned from even small and deteriorated textiles, allowing scholars to place them in their economic, social and cultural contexts.

4. Conclusions

Investigation of textiles and textile production in Etruria is still in its infancy and the field has much potential to develop further in the near future. Studies of the individual finds are constantly increasing the corpus of textile material. Statistical analysis of their technical data is finally permitting scholars to define chronologically and geographically specific characteristics of the textile material. Over the last 20 years, the field of textile archaeology has been enriched by a series of new scientific methods including isotopic tracing, radiocarbon dating, dye analysis, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray spectroscopy, CAT-scanning, DNA analysis, etc. (Good 2001; Andersson et al. 2010). Their systematic application to the archaeological textile finds of Italy is likely to generate valuable data on textile technology, chronology, provenance and preservation. Placing this information in its archaeological context will, in turn, help to clarify the larger picture.

Textile production was both a domestic and a commercial activity in Etruria. Spinning and weaving were carried out by the women of every household (Gleba 2008; see further, Chapter 21). Already at the end of the Bronze Age, the deposition of spindle whorls, distaffs and spools in female funerary assemblages testifies to women’s contributions to the communities as textile workers, and indicates that textile craft became a symbol of the female sphere (Gleba 2009; Lipkin 2012). While the regional significance of textile tools in burials is a matter of debate, most scholars agree that women, whether on their own or with the help of household slaves, produced not only most of the textiles needed by the household but also the fabric used for gifts and other exchange.

During the Orientalizing and Archaic periods, there is a significant increase in the scale of textile production, indicated by the large number and standardization of tools on settlement sites, as well as the standardization of certain textile types. In some cases, textile implements are concentrated in specific areas where other kinds of production, such as ceramic or metal, have been documented, suggesting a household or even workshop mode of manufacture and the existence of at least part-time specialist craftspeople. Cloth was likely produced for commercial purposes and textile trade has been tied to salt, amber, slaves, and other commodities (Gleba 2008: 195). Textile trade also seems to be indicated indirectly by the spread of fashion, for example from Etruria to central Europe (Hallstatt culture). Our understanding of the organizational aspects of the Etruscan textile production and trade, however, is far from complete and still requires detailed regional studies. Moreover, textiles produced by the women formed an important part of public rituals, as indicated by numerous textile tools found in the votive deposits of important Etruscan sanctuaries (Gleba 2009; Meyers 2013 and her Chapter 21). Because the presence of textile tools in sanctuaries is traditionally tied to votive activities, they need to be re-evaluated in the light of the possible existence of sanctuary textile workshops.

An understanding of the development of textile production in Etruria is crucial to any attempt to set this technology in its social and economic context and to provide a more comprehensive view of textile production as an important and integral part of the ancient Mediterranean economy, giving it equal weight to other crafts such as the manufacture of metal and ceramic goods. The issue of textile production is also important for the investigation of craft specialization, workshop production, division of labor and gender. Finally, geographical and chronological variations in textile work as evidenced by differences in textile implements can help explain how these technologies were transmitted between different geographical areas.

REFERENCES

- Alfaro, C. and L. Karali, eds. 2008. Purpureae Vestes II. Vestidos, Textiles y Tintes. València.

- Alfaro, C., M. Tellenbach, and J. Ortiz, eds. 2014. Purpureae Vestes IV. Production and Trade of Textiles and Dyes in the Roman Empire and Neighbouring Regions. València.

- Andersson Strand, E. B. et al. 2010. “Old Textiles–New Approaches.” European Journal of Archaeology 13: 149–173.

- Barber, E. J. W. 1991. Prehistoric Textiles. The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Princeton, NJ.

- Bender Jørgensen, L. 1986. Forhistoriske textiler i Skandinavien/ Prehistoric Scandinavian textiles. Copenhagen.

- Bender Jørgensen, L. 1992. North European Textiles until AD 1000. Aarhus.

- Bender Jørgensen, L., J. Banck-Burgess, and A. Rast-Eicher, eds. 2003. Textilien aus Archäologie und Geschichte. Festschrift für Klaus Tidow. Neumünster.

- Bentini, L., and A. Boiardi. 2007. “Le ore della bellezza.” In P. von Eles, ed., 127–138.

- Bichler, P., ed. 2005. Hallstatt Textiles: Technical Analysis, Scientific Investigation and Experiment on Iron Age Textiles. Oxford.

- Bonfante, L. 2003. Etruscan Dress. 2nd edn. Baltimore.

- Buranelli, F. 1983. La necropoli villanoviana “Le Rose” di Tarquinia. Rome.

- Chen, H. L., K. A. Jakes and D. W. Foreman. 1998. “Preservation of Archaeological Textiles through Fibre Mineralization.” Journal of Archaeological Science 25: 1015–1021.

- Esposito, A. M. 1999. I principi guerrieri. La necropoli etrusca di Casale Marittimo. Milan.

- Fiumi, E. 1976. Volterra Etrusca e Romana. Pisa.

- Flury-Lemberg, M. 1988. Textile Research and Conservation. Bern.

- Gleba, M. 2008. Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy. Oxford.

- Gleba, M. 2009. “Textile Tools and Specialisation in the Early Iron Age Female Burials.” In E. Herring and K. Lomas, eds., 69–78.

- Gleba, M. 2014. “Wrapped Up for Safe Keeping: ‘Wrapping’ Customs in Early Iron Age Europe.” In S. Harris and L. Douny, eds.

- Gleba, M. and J. M. Turfa. 2007. “Digging for Archaeological Textiles in Museums: ‘New’ Finds in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.” In A. Rast-Eicher and R. Windler, eds., 35–40.

- Gleba, M. and U. Mannering, eds. 2012. Textiles and Textile Production in Europe from Prehistory to AD 400. Oxford.

- Gleba, M. and I. Vanden Berghe. 2014. “Textiles from Strozzacapponi (Perugia/Corciano), Italy: New Evidence of Purple Production in Pre-Roman Italy.” In C. Alfaro et al., eds., 167–174.

- Good, I. 2001. “Archaeological Textiles: A Review of Current Research.” Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 209–226.

- Grömer, K. 2005. “Efficiency and Technique: Experiments with Original Spindle Whorls.” In P. Bichler, ed., 81–90.

- Harris, S. and L. Douny, eds. 2014. Wrapping and Unwrapping Material Culture: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives. Walton Creek, CA.

- Herring, E. and K. Lomas, eds. 2009. Gender Identities in Italy in the First Millennium BC. Oxford.

- Lipkin, S. 2012. Textile-Making in Central Tyrrhenian Italy from the Final Bronze Age to the Republican Period. Oxford.

- Mamez, L. and H. Masurel. 1992. “Étude complémentaire des vestiges textiles trouvés dans l’embarcation de la nécropole du Caolino à Sasso di Furbara. ” Origini 16: 295–310.

- Masurel, H. 1982. “Les vestiges textiles retrouvés dans l’embarcation. ” Origini 11: 381–414.

- Metallinou, G., C. Moulhérat, and G. Spantidaki. 2009. “Archaeological Textiles from Kerkyra.” Arachne 3: 30–51.

- Meyers, G. 2013. “Women and the Production of Ceremonial Textiles: A Reevaluation of Ceramic Textile Tools in Etrusco-Italic Sanctuaries.” American Journal of Archaeology 117: 247–274.

- Morigi Govi, C. 1971. “Il tintinnabulo della ‘Tomba degli Ori’ dell’Arsenale Militare di Bologna.” Archeologia Classica 23: 211–235.

- Moulhérat, C. 2008. “Les vestiges textiles de la Nécropole Celto-Etruscque de Monte Tamburino à Monte Bibele (Monterenzio – Bologne).” In C. Alfaro and L. Karali, eds., 89–99.

- Nielsen, E. 1998. “Bronze Production at Poggio Civitate (Murlo).” Etruscan Studies 5: 95–107.

- Raeder Knudsen, L. 2012. “The Tablet-woven Borders of Verucchio.” In M. Gleba and U. Mannering, eds., 254–265.

- Rast-Eicher, A. 2008. Textilien, Wolle, Schaffe der Eisenzeit in der Schweiz. (Antiqua 44.) Basel.

- Rast-Eicher, A. and R. Windler, eds. 2007. Archäologische Textilfunde – Archaeological Textiles. NESAT IX, Braunwald, 18.–21. Mai 2005. Ennenda.

- Rast-Eicher, A., and L. Bender Jørgensen. 2013. “Sheep Wool in Bronze Age and Iron Age Europe.” Journal of Archaeological Science 40: 1224–1241.

- Roncalli, F. 1980. “‘Carbasinis Volubinibus Implicati Libri.’ Osservazioni sul Liber Linteus di Zagabria.” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 96: 227–264.

- Stauffer, A. 2002. “I tessuti.” In P. von Eles, ed., 192–219.

- Stauffer, A. 2003. “Ein Gewebe mit Schnurapplikation aus der ‘Tomba del Trono’ in Verucchio (700 v. Chr.).” In L. Bender Jørgensen et al., eds., 205–208.

- Stauffer, A. 2004. “Early Etruscan Garments from Verucchio.” Bulletin du CIETA 81: 14–20.

- Stauffer, A. 2012. “Case Study: The Textiles from Verucchio, Italy.” In M. Gleba and U. Mannering, eds., 242–253.

- Torelli, M. 1997. “‘Domiseda, lanifica, univira’. Il trono di Verucchio e il ruolo e l’imagine della donna tra arcaismo e repubblica.” In M. Torelli, ed., 52–85.

- Torelli, M., ed. 1997. Il rango, il rito e l’immagine. Alle origini della rapresentazione storica romana. Milan.

- Trucco, F. 2006. “Considerazioni sul rituale funerario in Etruria meridionale all’inizio dell’età del Ferro alla luce delle nuove ricerche a Tarquinia.” In P. von Eles, ed., 95–102.

- Tuck, A. 2009. The Necropolis of Poggio Civitate (Murlo): Burials from Poggio Aguzzo. (Archeologica 153. Poggio Civitate Archeological Excavations 3.) Rome.

- Van der Meer, B. 2007. The Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis. The Linen Book of Zagreb. A Comment on the Longest Etruscan Text. Leiden.

- Von Eles, P. ed. 2002. Guerriero e sacerdote. Autorità e comunità nell’età del ferro a Verucchio. La Tomba del Trono. Florence.

- Von Eles, P., ed. 2006. La ritualità funeraria tra età del Ferro e Orientalizzante in Italia, Atti del convegno, Verucchio, 26–27 giugno 2002. Pisa and Rome.

- Von Eles, P. ed. 2007. Le ore e i giorni delle donne. Dalla quotidianità alla sacralità tra VIII e VII secolo a.C. (Catalogo della mostra.) Verucchio.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

Since its first edition in 1975, Larissa Bonfante’s Etruscan Dress (new edition 2003) remains the unsurpassed reference to Etruscan dress and its development. The most comprehensive work to date on the subject of textile production in ancient Italy in general and Etruria in particular is M. Gleba’s Textile production in Pre-Roman Italy (2008), which provides a summary of the archaeological, written and iconographic evidence for textile production in Etruria and Italy from 1000–300 BCE. For more information on ancient textiles and textile production in general, see Elizabeth Barber’s Prehistoric Textiles. The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages (1991), which remains a sine qua non, while Textiles and Textile Production in Europe from Prehistory to AD 400 (Gleba and Mannering 2012) is the most recent sourcebook on European textiles. Both provide exhaustive bibliographies on the subject.