Epilogue

Refusing to Go Quietly

By 1970 Liberator had begun to show the signs of a declining publication. After ten years of publishing, the former pulse of the radical scene had all the markings of transition into an uncertain future. Internecine differences among the staff left only a small number of committed individuals in the magazine’s production ranks. Such struggles provide at least a partial explanation for the magazine’s decline. By this time, many of the central activists and writers who helped shape and define black radical politics and expressive culture had left the scene (and the magazine), either voluntarily or by force of circumstance. Yet characteristic of Watts, Liberator refused to leave the scene quietly. The January issue of 1970 listed four main editors and four staff workers. Editors were also listed as regional representatives: Bill Mahoney was assigned coverage of the South; Richard Price covered events on the West Coast; Richard Gibson, who managed to keep some semblance of integrity despite the controversy surrounding him, continued to supply the bulk of the international coverage; and Clayton Riley continued to document the local arts scene. Tom Feelings and James Malone were listed as illustrators, James Connor handled photography, and longtime secretary Evelyn Kalibala remained a reliable staffer. A thinning production staff would encounter difficulty carrying the full weight of the magazine.

A second reason for the publication’s decline was the variety of publishing opportunities that opened up to black writers in the latter end of the 1960s due to successful demands for social transformation. Watts knew, as he always had known, that with increasing popularity, black writers were beginning to receive critical acclaim in the white press, and it became more and more difficult to recruit and maintain a core staff of writers who could work on the cheap or for free, as they had done throughout much of the periodical’s career.

Occasionally, with its remaining days numbered, the magazine would receive a spark reminiscent of its peak run. Longtime radicals such as James Boggs published influential articles on radicalism and nationalism in Liberator even as the magazine slumped.1 And the emergence of newer voices, such as literary critic Addison Gayle and Toni Cade Bambara, alongside familiar writers, such as Riley, showed promise but would not be enough to keep the magazine alive. To a large extent, however, small, independent, radical black press outlets such as Liberator took a considerable hit in a climate dominated by ad revenue. The magazine’s meager budget could not compete in such an environment. The periodical, and other publications and workshop spaces that had served as intellectual training grounds, were still available to young writers, but the older mentors, such as John Henrik Clarke, John O. Killens, and Harold Cruse, had moved into later stages of their careers as educators and public intellectuals, though both Freedomways and the Harlem Writer’s Guild continued well into the 1980s. Although Watts needed as much community support as he could attract, he refused to place complete blame for the financial difficulties on publication costs alone. In addition, he had come to depend on the cadre of writers that, to his mind, he had helped popularize. No doubt envious of the white publishing world’s ability to attract (and pay) black talent, Watts left little to the imagination when he lamented that some “revolutionary” writers had seen fit to publish their works elsewhere.

A Jamaica, New York, reader shared with Watts a concern for where the new leadership of the black community would come from and what would be offered beyond invoking “the name of Brother Malcolm to cover up their own lack of direction or program.” The writer challenged Watts on the tone of an editorial, which questioned whether black revolutionary poets were offering a program toward liberation or simply spouting poetic obscenities to display their rage, ostensibly for white onlookers. The writer argued that Watts was disconnected from what was “happening in Black centers today,” since, as he saw it, “there are many programs,” although he did not identify any.2

Yet the radical content persisted despite the financial crunch and thinning staff. By the magazine’s end, Watts seemed to be taking a cue from Cruse, hurling fiery and often personal insults at movement activists. In his March 1968 lead editorial, Watts had criticized what he termed “verbal revolutionaries” who were moving “from community to community with their Afro hairdos, a copy of Fanon under one arm and ‘Quotations from Chairman Mao’ under the other arm … seeking to confuse and divide the Black communities in the name of Black Power or Black Nationalism.” This sentiment anticipated Gil Scott-Heron’s song, “Brother,” where a similar critique is made.3 Watts argued that not enough time was being spent on building or developing a program for black liberation, an issue that almost all self-styled radicals raised, but whose answers remained elusive. Instead, some individuals (he refused to name them at times) had turned the movement into an experiment in entrepreneurialism. While black nationalists were jockeying for public attention, he claimed alarmingly, “Whitey is taking care of business … he is cutting back the so-called anti-poverty programs, and city Police commissioners are issuing daily news releases to the effect that they are ready to ‘maintain law and order’ by shooting down Black people in the streets.”4 Hyperbole aside, Watts’s editorial effectively poked at the ways in which state power structures regrouped in response to urban rebellions rather than yield to assertive demands for political power, no matter how articulate, creative, or solidly based on clear evidence. Urban rebellions highlighted the search for new power arrangements in society. Yet by 1968, the rhetoric of law and order, and not the redistribution of political power and economic resources, ruled the day.

Dan Watts, who was proudly intransigent to his core, refused to belabor the fact that publication costs were far outpacing revenue. It didn’t matter. The magazine had served its purpose. However, in the last few issues of the magazine, he was forced to tell readers how financially strapped Liberator had become. In February 1970, Watts published a letter addressed to readers asking for subscriptions and reminding them of the importance of independent black outlets such as his. Just below the table of contents appeared the lament that printing costs would drive an increase in subscription costs. Reminding readers that Liberator was one of the first publications to introduce such writers as Amiri Baraka, Nathan Hare, Eldridge Cleaver, Ed Bullins, Harold Cruse, Addison Gayle Jr., Toni Cade, Clayton Riley, and Malcolm X, he encouraged readers to support black thought through their subscription to the magazine. “Liberator is the only independent, completely Black-owned magazine today which regularly offers strong political comment,” he urged. “Help us continue to print the inside truths on what’s going on today in our Afro-American communities, the country, and the world by giving us your financial support.”5

While Watts was still seeking to recruit new funding streams, he expressed bitterness toward the movement. Now that Black Power had stalled to a relative halt (although movement activities continued around the country), Watts took aim at leaders, as he had always done. However, as he had demonstrated with increasing velocity toward the end of the 1960s, the leadership class that found itself in Watts’s crosshairs was one produced by Black Power specifically, and the Black Radical Tradition generally. As his conflagrations with Baldwin and Ossie Davis earlier in the decade had shown, Watts was far from gun-shy. Now, at the end of the decade, Watts had begun to express disillusionment with the slogans that had seemed to at once stick to all forms of black organizing, and thereby stifle new ideas. By December 1970, Watts was no longer solely editorializing against the civil rights establishment. In this issue of Liberator, Watts revealed exasperation and deep frustration, perhaps with his own failed efforts to bring about a new political day for the struggling communities defended on the magazine’s pages each month. As the magazine’s tenth anniversary approached, Watts seemed to have little to celebrate. The magazine was thinning in size and revenue, although it could still attract talent, as seen in the writings of Toni Cade and Ron Welburn. It also kept ties to local community organizations based in New York City such as the Brownsville Community Council and the Young Black Political Action Committee.

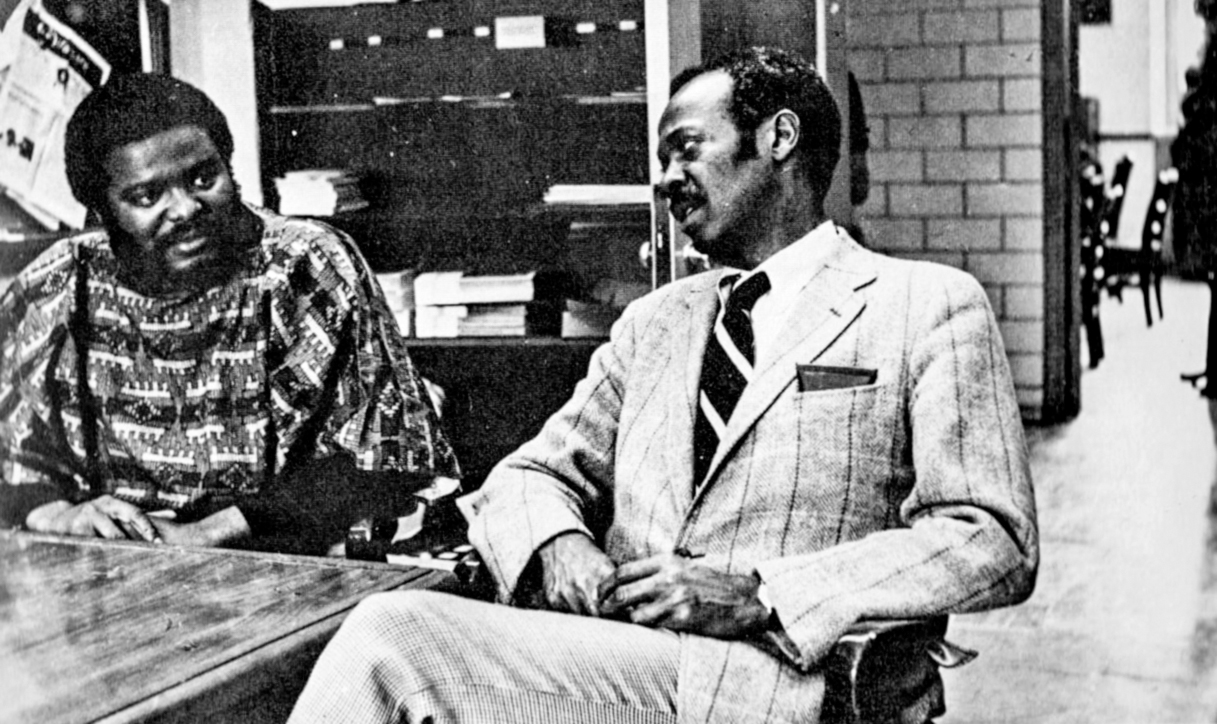

Dan Watts and student Quinton Wilkes, Fordham University, from the 1971 Yearbook. Watts taught at Fordham from 1969 to 1971, the last two years Liberator was in circulation. Maroon Yearbook 1971, courtesy of Fordham University Archives.

In Watts’s December editorial, which was blandly entitled “Big Brother,” his exasperation surfaced all too clearly. In his mind, grassroots mobilization, the defense of workers, and coalition building had given way to top-down only organizing and self-aggrandizement rather than material improvements. His style would not allow him to placate those who still found some political refuge in what was left of movement politics, even if only as a marker of evaporated possibilities. “Black elites, while espousing endless and program-less rhetoric of Black Power, are discarding (in the name of revolution) the fundamental humanistic values that allowed us to survive the long ordeal of slavery. They are straying away from the people,” he wrote. The people, in Watts’s view, were being lost in the maelstrom of conference planning, speech making, conventions, and lecture circuits, he bemoaned. “So much of our rich African heritage is being dissipated in orgies of Blackness without providing one vehicle for the transfer of power from those who hold it to the powerless mass of Afro-Americans.” Watts saw himself as part of this gap, but by calling attention to it in a manner reminiscent of the irascible Harold Cruse, he hoped he might also play some part in the solution. Watts had observed, and often stood at the center of, several divisions among black activists. He argued with many, and shared panels and press conferences with numerous others. As an editor of a decade-long radical publication, he knew, at least to his mind, exactly what he was talking about. Though one of Watts’s last editorials concluded on a rather defeatist note, he saw it as his self-appointed responsibility to lay the facts bare and, true to form, to grind an ax or two in the process: “Today in the name of ‘Power to the people’ lives are being ripped off, bodies are being broken, thousands of eager young Black minds are being poisoned with the irrelevant claim of ‘beauty and truth lie in conformity to the gospel of the self-anointed spokesmen of the moment.’ ” It is unclear if this was a veiled critique of Whitney Young, Amiri Baraka, or others. Though it appears that his attitude toward charismatic leadership had changed considerably from years prior, when he too was among those vying for the spotlight. Watts, now in his mid-forties, had grown disenchanted with the prospects of top-down leadership. Strikingly, Watts’s final point must have caught faithful readers off guard. Urging an embrace of “diversity” within blackness, Watts discarded the singular call of unity that had long been a hallmark of black political thought across the board. “We are a proud and diversified people,” he urged, adding, “Our survival lies in the very nature of our diversity and not in becoming slaves to an inhuman institution called oneness.” This was a far cry from the hard-charging collectivist mindset that Liberator readers expected. Watts’s editorial spoke volumes about Liberator’s future. If oneness or some semblance of unity within the race was an expired concept, then what would, or could, black solidarity mean? Perhaps this was the feeling of regret that was overwhelming Watts. Perhaps it was pragmatism tugging at his politically ambitious heart.6 Watts’s tone in this editorial suggests that he was looking ahead, and not necessarily back at the last ten years. In 1969, Watts had accepted a post at Fordham University as a lecturer in Black Studies (one of the first wave of such programs in the country) and director of the Higher Education Opportunities program, heading up a budget that included a grant of $684,000 from the New York State Department of Education to aid up to 700 economically challenged Fordham students.7 He taught courses on the History of the Afro-American Press and Propaganda in the Black Community from 1969 to 1971.8 Though it may have seemed odd that someone who had eschewed the corporate world of architecture would now take a position at a prestigious American university, Watts was in the same position of many former movement activists, in that they were looking to continue justice work when and where possible. For some this meant honing one’s craft and marketing oneself to the mainstream, and for others, this meant going into some form of work in the academy.

At its tenth year, Liberator was still reminding readers of its pivotal role, listing its top reasons why readers should obtain or renew a $4 yearly subscription. Among the reasons provided, it boasted that its “compelling approach to journalism has made it the only magazine of its kind today.” Proudly, Watts asserted, “We not only report the news, we help make news,” with “penetrating analysis of trends in Afro-American communities and in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.” Finally, Liberator was the place to turn to if readers wanted to “keep up with a changing world.” In many ways, the periodical lived up to its bold claims. However, as a publication it was merely a vehicle of movement ideas, and could only accompany and document action. Though it could not bring about revolutionary change, it could represent a key role in how people understood revolutionary activity in the United States and around the world. Black communities needed as many outlets as possible to think out loud, argue, revise, strategize, and most of all, fight.

Watts’s last editorial appeared in March 1971 and underscored the demise of Black Power rhetoric. Rather than lamenting the further misdirection of black leadership or bemoaning the lack of resources in the black community (or for his magazine), he simply reprinted a recent cartoon, in which a young man and woman who look like hippies are shown in front of a billboard advertisement for a gasoline company. The billboard features a man’s hand gripping a gas pump, and written boldly across the top portion of the sign are the words: “All Power to the People!” The words from the couple ruefully express the co-optation of the once-popular and controversial phrase: “I guess it was bound to happen … sooner or later.”9 Though the remaining contents of this issue were potentially fecund, including the work of six new poets, two short stories, and a few timely analyses, this would be the last issue to hit the stands.

______

Though Liberator made a critical impact on the period, it was by no means the only place one could find Black Arts and Black Power ideas being expressed and debated. Yet for its time, it recruited and disseminated some of the most cutting-edge radical black thought available. The periodical was an instrument of liberatory activist practitioners who were part of a larger global community of scholars, students, trade unionists, and everyday activists seeking to define, shape, and shake up the direction of black liberation. Publications such as Liberator, alongside peer-rival publications such as Freedomways, Muhammad Speaks, Soulbook, and Negro Digest/Black World, as well as lesser-known and short-lived journals, such as Onyx, were crucial to the creation and circulation of African American transnational ideas about culture, politics, economics, education, and religion and spirituality in the 1960s and 1970s.

These sites of radical thought are therefore of indispensable importance when evaluating this period. These periodicals were Black Studies departments before American universities and colleges were forced to embrace the Black Studies and Ethnic Studies movements. They were training grounds for numerous cohorts of activists, groups, and individuals. They were sites of strategy and planning. They were spaces of critical interrogation of governmental policies that anticipated the CNN network’s all-day political punditry and the age of contemporary public intellectualism. On this score, they also serve as a marker for how much African American and Afro-diasporic cultural and political thought in the public domain has deteriorated; how far African Americans have moved from the demands for change vividly and eloquently expressed by Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Houston Baker, who also published in Liberator just prior to its closing, has made a compelling argument that many public intellectuals—especially the wave of black conservative thinkers, but also so-called progressives who frequent the lecture circuit in our day—have betrayed the legacy of King and the entire period of heroic civil rights.10 Taking a cue from Baker’s critique, in some ways Radical Intellect asks what would Dan Watts, Larry Neal, Harold Cruse, Lorraine Hansberry, John Coltrane, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, and Malcolm X have to say about the election and reelection of the first African American president and our present cultural moment that marks a resurgence of white nationalist sentiment, xenophobia, and misogyny? What programs would they suggest African Americans follow? What would they have to say about the (limited) potential of electoral politics? What music would they create? What poems and plays would they write? What speeches would they give? In some ways we have recently witnessed the reincarnation of these voices in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as Moral Mondays in North Carolina, and courageous fights against the disruption of Native soil through the building of a gas pipeline. These efforts are reminders that the voices and hearts dedicated to struggles for justice have not disappeared, but are rather given new life through the subsequent generations of activists, writers, and artists.

Radical Intellect is about an orbit of writers, thinkers, and activists who celebrated and fought with and often alongside one another while engaged in a politics of liberation. It is about how these activists grappled with history, politics, and culture as they were making history. History is often unkind to the lesser-known figures, such as community activists, artists, agitators, skilled debaters, collectors, bibliophiles, educators, lay historians, curators, and dedicated strategists. Yet these figures, as much as those who are better known, help to fill out and accurately represent attitudes not accepted in the mainstream, especially concerning black politics. Liberator was one such site for an assembly of voices that made history by not being afraid to openly challenge the status quo and publicly disagree with the expectations of respectable leadership. As the Palestinian scholar Edward Said once put it, “Every intellectual whose métier is articulating and representing specific views, ideas, ideologies, logically aspires to making them work in a society. The intellectual who claims to write only for him or herself, or for the sake of pure learning, or abstract science is not to be, and must not be, believed.”11 Called into activism by the requirements of the day rather than by vocation, Liberator’s intellectuals stretched the political and artistic imagination. As self-styled activists, few were concerned with recognition from political elites if such proximity did not generate the influence to enact their visions. Publications such as Liberator and the range of voices that filled its pages contributed to the creation of transformative political and cultural spaces and practices. Liberator writers, artists, and activists would have to navigate a hostile world not of their making and wholly indifferent to black suffering. But they did not go quietly. As both witnesses and participants, African American activists and budding intellectuals critical of the mainstream could speak candidly and critically about the major issues of the day as they saw them. For this reason, publications such as Liberator must ever be remembered for the example they set in providing courageous, innovative, imaginative, and unapologetic truth telling, a practice as urgently needed now as then. As Curtis Mayfield once sang, we must “keep on pushin’.”