Space is a fundamental aspect of Varda’s cinema, and one that both critics and the director herself have underlined very early on. Alison Smith, for example, devotes a whole chapter to ‘People and Places’ (1998: 60–91) and Kelley Conway more recently identifies geography and emotion among Varda’s perennial preoccupations (2009: 212). Varda has always been fascinated by space and writes that her work consists in capturing the light on inhabited landscapes to offer it up to the spectators of her films. ‘Entre […] dans mes films, c’est ouvert, il y a de la lumière, du moins celle des paysages avec figures que j’ai filmés’ (‘Come into my films, the door is open, there is light, the light captured on the inhabited landscapes that I have filmed’) (Varda 1994: 6). This tripartite emphasis draws our attention to the landscapes and their inhabitants, the uncertain capture of light onto film, and the director’s inner desire to offer these to us, the audience.

In each film or artistic project undertaken by Varda, there is a specific modus operandi which is determined by the location she focuses on. Her filmography shows that she enjoys working in a variety of places, maybe because Varda’s youth was characterised by geographical movement. Scholars have often privileged her Parisian films (see, for instance, Mouton 2001, Forbes 2002 and Morissey 2008) even though recently her peripatetic, provincial and expatriate works have been the focus of more intense scrutiny (for more details see Bénézet 2009, Powrie 2011 and Boyle 2012). In this chapter, I will straddle this divide and discuss an apparently eclectic corpus of films to see how Varda understands space and how she uses it in her cinema. In her work, space is neither objective nor topographic. It is not a blank canvas or a tabula rasa on which the filmmaker can build anything that she wants. As I have written elsewhere (Bénézet 2009: 87), Varda’s perspective is close to that of cultural geographers who argue that space is socially constituted through the interaction of boundaries, representations and practices (see Davilà 2004: 75). Varda attended some of Gaston Bachelard’s lectures in Paris and although she claims she did not understand much, her practice seems to be steeped into a phenomenological and relational understanding of space that I will examine through a set of particular cases. In Poetics of Space, Bachelard distinguishes between abstract space and lived space and recognises that in the second half of his career he moved from a rationalist to a phenomenological approach (1969: xi–xii). Like her professor, Varda believes that lived or inhabited space is known phenomenologically through participation in or inhabitation of the world. How Varda renders this experience of space on screen is what I examine in this chapter. How is Varda approaching space when she films or sets up installations? What is she looking for in a particular space? And are there common elements that she focuses on in her otherwise disparate filmography? These questions form the core of this chapter. To cover as much ground as possible, this chapter will be organised around two main sections discussing, first, the notion of emotional geography and, second, the relational modus operandi of Varda’s work.

1: Emotional Geography

In Varda’s films, as soon as space is observed or physically experienced (by being walked through, for example), it becomes invested by someone’s presence and by his or her embodied subjectivity. This space may remain mysterious and uncontrollable to the subject but its depiction changes drastically. In L’Opéra Mouffe discussed in chapter one, the many experiences of the pregnant woman of the title influence the cascade of free associations that the spectator is exposed to. While we cannot be sure how many subjectivities invest the film (is it just that of the pregnant woman or a collection of female experiences including those of the lover?), this work illustrates that Varda will not, even in a short film portraying la Mouffe in 1958, separate her documentary images from the visual notes and impressions of an individual, whether it is herself, an alter ego, or more simply a set of characters. The term ‘subjective documentary’ that she coined to talk of L’Opéra Mouffe demonstrates how in this particular case La Mouffe cannot be separated from the woman of the title and the director.

This is also true of Varda’s fictional works. Cléo de 5 à 7 chronicles ninety minutes of the life of a rising pop singer who is waiting to hear the results of a biopsy. The progress of Varda’s Parisian heroine has been analysed by many scholars in terms of space, most following in the footsteps of Flitterman-Lewis’s analysis (1996) interpreting the protagonist’s journey as one of self-discovery. Varda’s exploration of the connections between a specific environment, here the city, and a character is an obsession that she openly acknowledges but she also emphasises that it is the dialectic between an embodied subject and a specific space that she is interested in: ‘This question of space and people on film concerns the body in film because it is also made by people’s bodies. I don’t think we can talk about Cléo without remembering, all the time, that she’s a beautiful, tall, blond woman who is in danger, who is attacked by fear and by illness. We cannot forget either that Mona is a woman, maybe hidden under these strange leather rotten clothes that she is wearing’ (Varda et al. 2011: 190). In Cléo de 5 à 7, the spectator is taken in an array of places, from Cléo’s hyperfeminine boudoir where she performs for her lover and composer to the café Le Dôme where she observes and listens to the people around her.1 Her itinerary is not a fixed one as she is mobile and able to change her mind whenever she wants to. She is, for instance, taking a taxi with her assistant Angèle at the start of the film and then using public transport with Antoine, a soldier on leave from the Algerian war that she meets in Parc Montsouris.2 The incoherence and unpredictability of the city are here inspirational and celebrated.3 When Cléo leaves her flat upset and starts the unaccompanied walk that will ultimately take her to the hospital to hear that she does have cancer, she ‘ceases to be an object, constructed by the looks of men, and assumes the power of vision, a subjective vision of her own’ (Flitterman-Lewis 1996: 269). She is finally by herself and in charge, willingly soaking up the changing and fleeting sights of the city and opened to chance encounters. The idea of movement and change is essential in this section of the film as suggested by Özgen Tuncer: ‘The female protagonists who are on the move not only constantly elude fixating and sedentarising powers, but also trigger a transformation in the territories they travel through’ (2012: 114). Cléo is literally on the move but as she leaves her flat, she is also escaping the diva and starlet stereotypes that her entourage seems keen to associate with her. She is making the choice to leave and go wherever chance will take her, whether it is the sculptor’s studio where her friend Dorothée is posing, or the local theatre for a cinematographic interlude. The changing interaction between Cléo and her environment and the discussions (open or veiled) about time and death can be regarded as the two founding principles of the film. Thus looking at the dialectic between the varied landscapes and Cléo’s evolution provides the audience with a better understanding of the emotional landscapes that Varda’s films construct.

Another eloquent film literally built on this dialectic between space and characters is Plaisirs d’Amour en Iran, which was meant to be screened before L’une chante, l’autre pas. Varda made this six-minute film with two usual suspects, Nurith Aviv and Sabine Mamou, in Teheran, Ispahan and Cairo during the summer of 1976 and used the characters of L’une chante, l’autre pas played by Valérie Mairesse and Ali Raffi. The film is unapologetically presented like a fiction when it opens with the off-screen voice of a woman saying: ‘Il était une fois un homme et une femme qui étaient amoureux à Ispahan en Iran’ (‘Once upon a time there was a man and a woman who were in love in Hispahan in Iran’). As she speaks, the spectator sees a series of long shots of a beautiful mosque visited by tourists and locals including a young couple. The narrator explains that the couple is astounded by so much beauty and amazed to see and feel for the first time the effects of the total harmony between architecture and nature as well as between their environment and their body (‘l’harmonie entre nature et architecture, entre corps et décor’). Two conversations between the lovers follow this establishing scene, the first begins with a medium close-up of the two protagonists but continues off camera while we see images of the contours and details of the surrounding building. The second is different because its setting is more private as the couple sits on the edge of a fountain in a little shady courtyard (maybe their hotel). The subject of their exchange shifts slightly from the description of their erotic sensations, when they are off screen, to the declamation in the courtyard, on screen, of two love poems, the first learnt by heart by the man, the second audacious and improvised by her in response to his ceremonious declaration. The scene closes on their embrace even if he jokingly proffers that she does not understand men at all while she answers that the feeling is mutual (‘Him: Tu ne comprends rien aux hommes; Her: Et si c’était réciproque?’). The film then shifts to a series of close ups on Persian miniatures representing a couple embracing followed by groups of men and women who are described and linked to the story of the couple by the female narrator’s voice-over. The last miniature by Behzād (1488) showing the couple Yusuf and Zulaikha in a huge and sumptuous palace provides a link back to the royal mosque’s architecture in Ispahan. The narrator carries on explaining how this space where nature and culture and profane and sacred art meet is a truly sensational place for lovers even if they are fictional characters (‘C’est un lieu troublant entre tous pour des amoureux même s’ils sont les personnages d’un film’).

The two lovers of Plaisir d’Amour en Iran embracing in the private courtyard

Behzād’s version of the lovers Yusuf and Zulaikha

Although made over thirty years ago, this film exemplifies many of the elements that Varda requires from the places that she incorporates in her work. What she seems to be looking for above all is an evocative space which will be able to trigger and generate associations and new images in the spectator’s mind. In a statement published for one of her recent exhibitions, Varda explains that she aims to make images with the potential to surprise, provoke and trigger thoughts and rêverie in her audience: ‘Je voudrais que ces images, fixes ou animées, créent des surprises, éveillent des pensées et suscitent des rêveries’.4 Plaisirs d’Amour en Iran achieves this by meshing the couple’s thoughts with the ornate details of the mosque as well as the miniatures and by establishing connections between three different love poems with very different tones. The film is permeated by their joyful celebration of sensual love, but it also translates a sense of admiration for art, whether it is architecture, poetry or visual art. The domes of the mosque take on a surreal existence when she compares them to pairs of breasts, and we start to realise that things may not always be what they seem. From then on, the audience will be more likely to look for risqué hints both in the couple’s dialogue and in the images that they see. The landscape is not a simple exotic background; it literally takes on a life of its own and changes according to the content and intonations of the couple’s intimate conversations. Interior and exterior worlds become bound through the combinations of the images and dialogues on screen. We know, for instance, that the lovers listen to their drives when they say that they are hungry or thirsty, and in so doing they explain how this particular space has an impact on them.

From the moment we hear them talk, lightness and sensuality seem to pervade the sacred place of the mosque. The lavish motifs and shapes on the mosaic walls evoke a garden where love flourishes. From the shady courtyard with its small trees and flowers to the ornate designs of the miniatures, gardens are an important element of the film connecting the lovers with their environment, the miniatures and poetry. In the first poem that he recites to her in Arabic and then translates, the poet compares his lover’s body to a garden. The quote from Paul Éluard’s poem ‘Je ne suis pas seul’ (‘I am not alone’) read by the voice-over narrator synchronised with the miniature of a poet alone in a garden, is also significant.5 In the final lines of his poem – ‘Je parle d’un jardin, je rêve, mais j’aime justement’ – Éluard makes it clear that he is not just describing an imaginary garden but that he is alluding to the woman he loves. The garden’s flowers, the fruits, the sun and the rain summon her beauty and her material presence. They enable the poet to feel as if she was here by his side. The space he is in becomes entangled with his memory of her and his proclamation of love. In Varda’s film, the lovers’ experience of space, their enjoyment of sensual love and their aesthetic response to architecture and poetry also become intertwined.

If the two lovers were the spectator’s only guides, the film would be a parodic portrayal of intercultural misunderstanding or a simple vignette about the tribulations of love. In fact, she is enjoying his company but seems unaffected by his love of grandiosity and performance; while he clearly finds her directness titillating but also a little bit shocking. When she writes her love poem on a toilet roll and describes him as a man-bird with a gentle and proud tail, he cannot refrain from telling her that she cannot be serious and uses one of the most clichéd statements about the inability of women to understand men and vice versa. The narrator, who could be considered the director’s alter ego, is the one perfecting the surreal symbiosis on screen. The landscapes and gardens, their artistic representations and the lovers’ embodied experiences become inseparable thanks to her suturing of these fragments. We are watching more than a comical and sensual evocation of love and its misunderstandings; we are offered a chance to think about what sensory and intellectual apprehension is beyond or rather through artistic representations. The emotional landscapes that Varda creates are not only subjective and contested but also self-reflexive. As Powrie concludes in his article on Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Varda is keen to show how the process of filmmaking becomes a ‘vehicle for transforming the everyday, for revealing what the surrealists called the marvellous’ (2011: 75). This idea of transformation through connections is one that I want to elaborate on because it almost seems to become a method for Varda when it comes to space. Analysing the connections created between space and various other elements will also help to establish the originality and consistency of Varda’s poetics of space.

2: A Relational Modus Operandi, or How Space Establishes Multiple Connections in Varda’s Films

In the film that she said would be her last, Les Plages d’Agnès/The Beaches of Agnès (2008), the beach is a common thread which enables Varda to connect an otherwise often disparate set of memories. This work was described as an autobiographical film and as a cinematographic self-fiction (see Boyle 2012). What I find particularly interesting in Les Plages d’Agnès is that Varda presents her own identity as determined by the ever-shifting relationships that she has had with the beaches of her life. The philosopher Frank Kausch rightly calls it a ‘portrait en creux’ and foregrounds the elements that are in contact with and transforming Varda’s identity.6 Varda’s modus operandi, her way of establishing connections may be more apparent in her recent projects, but I would argue that she was already using a similar strategy in earlier works (including commissioned projects).

(A) Du Côté de la Côte, O’ Soleil, soleil and Eden Toc

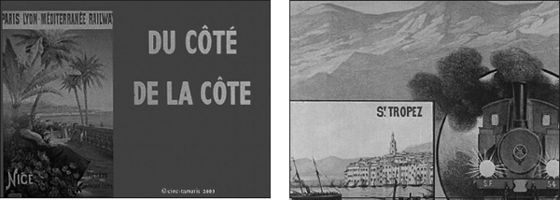

Du Côté de la Côte (1958) is a fruitful example of Varda’s approach when it comes to space. This film was commissioned by l’Office national du tourisme (the French tourism office) and was supposed to promote tourism on the French Riviera. It was made with a small team, on a decent budget and with material that Varda was happy to experiment with, like tracking rails. She spent eight weeks on site and ended up editing a very personal vision of this region. The film was finally released in June 1959 in Paris and screened with Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour. Unlike Plaisirs d’Amour en Iran, Du Côté de la Côte is presented as a documentary. From the beginning, the off-screen male narrator explains that tourists and crowds are going to be the film’s main subject, not the locals: ‘Notre propos n’est pas de cinématographier les indigènes, toujours vieux et charmants […] notre sujet c’est la foule, les touristes, les curieux…’ (‘Our purpose is not to film indigenous people, who according to custom are always old and charming. […] Our subject is the crowd, the tourists, the curious people…’).7 This declaration of intention almost sounds like a disclaimer explaining why the filmmaker does not embrace a more discreet cinéma direct approach that would focus on the locals rather than on their seasonal counterparts.8 At the same time, this tongue-in-cheek opening also reminds us that the documentary we are about to see is decidedly subjective. And why should this not be since, as the narrator explains, there is no consensus about who invented, created and perpetuated the set of images generally associated with ‘La Côte d’Azur’? Out of this abundance what Varda does in Du Côté de la Côte is to juggle with the garish images and clichés about la Côte, some archival footage and reproductions and her own often Tati-esque footage to assemble an original and exuberant picture of the Riviera. This film which is as much an essay as a travelogue operates vis à vis space in two ways that require attention. Two types of connections will be then investigated: I will look first at how Varda addresses the mythology surrounding the Riviera and how she introduces the marvellous and poetic. The second set of connections are the ones she establishes between herself as a visiting outsider and the audience.

From the very beginning, Du Côté de la Côte simultaneously focuses on two things: the roots and ‘constructedness’ of the idea of the Riviera, and the current practices of space exemplified by the tourists. The credits accompanied by a collection of panoramas and vintage promotional posters showing the sights of Cannes, Antibes, St Tropez and Menton immediately establish that the film is not going to limit its attention to one city. These colourful images are synchronised with the song of a bel canto tenor who praises each location by repeating ‘la più bella’ (the most beautiful) after each poster so that the sequence resembles a list of the top places to visit found in most travel guides. Gorbman interprets this musical opening as ‘tourist music’ even if it was ‘composed by Georges Delerue to Varda’s lyrics’ (2012: 48). ‘Imitating the sunny tunes of itinerant musicians who circulate among tables in Mediterranean dining spots, and […] accompanied by guitar and mandolin’, she labels the lyrics as ‘du toc – fake Italian or perhaps fake Provençal – successively proclaiming each coastal town (Nizza, Canna, Antiba, Saint-Tropez, Mentona) la più bella, the most beautiful of all’ (ibid.). From then on, it becomes evident that Varda is going to be a rather unorthodox guide that I would describe as an inquisitive anthropologist. First we learn how much tourism impacts on the demography of small cities like Cannes and St Tropez, and who were the first figures to put this particular area of France on the map of seasonal tourism. The male narrator mentions Cornelia Salonina (the wife of a Roman emperor), the Cardinal Maurice de Savoie (on his honeymoon) as well as Lord Brougham and Queen Victoria, while the female narrator whispers the name of each of the locations (respectively le Cimier’s water spa, Nice and finally Cannes).9

Opening credits of Du Coté de la Côte (left); vintage promotional posters for St Tropez included in the opening (right)

Varda’s perspective can be compared to that of a stroller-historian as defined by Sylviane Agacinsky:

The historian takes possession of the past by interpreting traces, whereas the trace of the past happens to the stroller and takes possession of him. Let us not claim, however, that nothing happens to the historian; undoubtedly his desire also involves an anticipation, a curiosity with regard to what will come to him from the past, what he will discover in the shadows and encounter. There is often a stroller at the heart of each historian, a part of him that is trying to let himself be touched by the traces. (2003: 52)

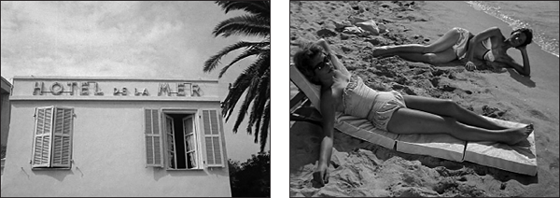

Varda shows curiosity, a desire to capture and make sense of traces of the past, and a willingness to be touched by what she encounters during this summer of 1958. Although anchored in the past via an array of eclectic references to historical figures and artists like Picasso, Valéry, Colette and Matisse, the film is also interrogating the way people currently inhabit the region, whether they are famous like Brigitte Bardot, or anonymous like the crowds of the opening. The mythology associated with the Riviera is made tangible through black and white footage of Bardot and Sophia Loren, and a long sequence on the architecture of palaces such as the Negresco and the exuberant private villas. We are told how these sights are magnets for tourists and how their attention naturally shifts from these unattainable ideals to far more easily consumable places like the gardens, museums and beaches of the coast. There is humour and irony in this portrayal of the coast. Tourists and buildings alike are prone to changes in fashion: ‘yellow and blue are in one year’, though green seems to be the colour of choice for Germans. Delerue’s use of the brass, reminiscent of the music matching the gesture sequence in L’Opéra Mouffe, turns a successions of sunbathers coming in and out of the same tent on the beach into a comical ballet. Tati’s similar use of human movement in space in the modernist architecture of Playtime (1964) comes to mind. The artificiality associated with what Varda calls ‘l’Eden toc’ (the fake or gaudy Riviera) comes to the fore on many occasions. This array of sights leaves the camera dizzy and the spectator uncertain that there is any essence behind these colourful surfaces. With the pomp and luxury of hotels and villas, Varda contrasts the more democratic spaces of the beach, the camping site and the cemetery. Although space is also at a premium in all these places, there is a sense that they reveal as much if not more about the Riviera as the glossy images usually associated with the region. More than an idealised or promotional ‘idea’ of the Riviera, these are material places which are truly lived in or which resonate with the living.

L’hôtel de la mer, an example of the local architecture and its bright colours (left); bright colours are fashionable too when it comes to swimsuits in 1958 (right)

The long section at the end of the film documenting the carnival in Nice is another significant sequence, especially since the narrator provides only very spare commentary. In this passage, we see very little of the streets or buildings because the camera focuses on the revellers and on the giant papier maché puppets and masks which are paraded for twelve days through the city. The dancing, the fireworks and the burning of the king’s figure accompanied by loud brass band music create the frantic atmosphere and topsy-turvy universe where hierarchy and inequality have supposedly no place. One could say that in Nice the carnival has become more inclusive since it has evolved historically from a set of private balls and receptions in the thirteenth century to a boisterous celebration for all. But when Varda’s camera lingers on several women who are repeatedly held captive by a group of men to be covered with confetti, we come to the conclusion that the carnival is only a temporary safety valve and that inequality and divisions between the sexes are still manifest. Whether it is the dream or the celebrations that tourists are after, it is clear that these are manifestations of a shared need for escapism and utopia. In Du Côté de la Côte, Varda deconstructs some of the myths the Riviera is built on, and sheds light on the lingering gap between the more and the less privileged. The egalitarian ideal associated with the carnival can neither live on nor change things radically. The only two comments of the male narrator heard just before and after the carnival sequence confirm that it should be looked at as a temporary and limited event: ‘De la nostalgie naît le carnaval’ and ‘le Carnaval brûle […] le carnaval est mort, le silence va régner’ (‘Nostalgia gives way to the carnival’ and ‘The carnival burns […] the carnival is dead, silence will reign’).

A close up on one of the women held captive during the carnival in Nice

Even if the carnival will neither resolve tensions nor appease longings, the ending of Du Côté de la Côte suggests that all is not lost because ‘l’Eden existe’ (‘Eden exists’). The paradisiac island where a naked man and woman nap undisturbed is beautiful and peaceful, an improbable sight after the crowds that Varda’s camera has favoured until now. The gentle melody of the flute matches the slow movements of the camera caressing the waves, the sand and the branches, before it finally lingers over the couple’s back. The close up of their hands marks an important switch since it is the female narrator who takes over for the conclusion. In this final sequence, her sober and melancholy voice explains that fantasies (‘les rêveries collectives’) are only ethereal ideas, whether one thinks of a perfectly manicured garden, the Riviera or Eden. As a series of gates and beach umbrellas are closed against grey skies, a song about the fleetingness of the summer starts which says how sad and silly the end of a party and of summertime can be (‘le soleil de la fête, il est démaquillé, c’est triste et bête, la fin de la fête, la fin de l’été’). This is a melancholy, poetic and sensible conclusion to this vertiginous travelogue. After showing the fakeness and illusive quality of ‘la côte d’azur’, Varda acknowledges her own desire to make this place more beautiful and dreamlike. Her unorthodox deconstruction does not result in a completely cynical ‘so what’. On the contrary, the comical, poetic, and unexpected connections that the film establishes between the spaces of ‘la côte’ and its tourists create a vivid and joyful picture of the Riviera at its peak, that is to say in the summer. Varda’s unorthodox connections suggest that the fabrication of the Riviera opens up endless avenues to her imagination and that of her spectators who are invited to dream of many more. Her travelogue may be dizzying at times because of its eclecticism but by transforming the everyday and mundane (like hats and parasols) into something marvellous (flowers and crowns), Varda proves that she is a relentless ‘enchanteuse du quotidien’, a true enchantress.

Since the film was conceived as a promotional assignment, it is not surprising to find references to the dazzling glamour and widespread attraction that this region has over people in general. Through her presentation of the history and fabricated myth of the Riviera Varda also tries to establish visceral connections to the spectators and to touch them. People who saw Du Côté de la Côte were, apart from the film buffs and journalists who attended the film festivals of Tours, Obenhausen, Brussels and Berlin, either the ones who went to see Hiroshima mon Amour in 1959 or people living in the half million (or so) French households who owned a television in that same year.10 At that point in her career, Varda had not made a feature, so she was not well-known. Du Côté de la Côte, contrary to some of her other more fictional works, does not contain characters per se, so it does not lend itself to easy effects of identification. As remarked earlier it does not rely on a simple talking head either, but on an unusual duo and on Delerue’s music. It almost feels like one is playing a game of hide and seek when trying to locate the director’s presence. But there are moments where she surfaces, and during these occurrences, Varda, the outsider, establishes connections with the audience throughout the space of la côte.

In Du Côté de la Côte, the Riviera becomes a giant stage ready for its many performers; it is lived in, animated and embodied through colourful characters. These may be anonymous bathers and tourists, but they make the experience of the coastal beaches tangible well beyond dreams of fame and limelight. Varda’s editing combined with Delerue’s music and the narrator’s commentary are conceived to trigger reactions in the audience. In the beginning of the film, for instance, we see a long row of bathers on the beach lying down in tight rows like sardines in a box. The end of the tracking shot reveals a surprise when the couples give way to a mismatch of women and children, with one woman in particular wearing a stripy bathing suit who caresses a dove, while three others rest on her belly and towel. The commentary which describes the subject of Du Côté de la Côte matches these images of the symbol of freedom: ‘les passagers qui découvrent un jour cette côte et s’y assemblent pour épuiser leur temps de liberté’ (‘the temporary occupants who one day discover this coast and decide to flock there to use up all their free-time’). After a momentary pause on the lady with the doves, a pirouetting movement of the camera mimics the effect of this vertiginous array of bodies on the beach and the caustic nature of the commentary hits you: why is it that people come to this overcrowded region in the first place? And why do they keep on coming? The paid vacation granted to French workers for the first time in June 1936 has just been extended in 1956 from two to three weeks and the seaside’s popularity shows no sign of abating. The sea, the sun and the aura of movie stars remain favourites. Varda is not completely cynical, since her film simultaneously shows the artifice and some of the Riviera’s artefacts on screen. In her conclusion, she embraces the natural beauty of the region and even acknowledges its appeal on herself. In a way, she recognises the longings associated with ‘la côte d’azur’ from the very beginning, a place that seems so close: à côté (close by) so to speak, but also distant and pure with its incredible Azure landscapes.

Varda is not a local and the film does not suggest at any point that the director or narrator know more about the region than the spectators or tourists. The film comprises much information but it always feels tentative and inquisitive about its findings rather than purely didactic. To keep the viewers on their toes and trigger their reactions, Varda alternates between brief fact-based sections and cascades of free associations often characterised by humour. Some of these sequences are clearly built like colourful ballets of bodies. There are casual walks on the promenade akin to fashion shows, close ups of tanned and burned skin, and shots of napping beach lovers captured at an angle which gives the comic impression that their head has been replaced by that of a toddler or a dog. Varda repeatedly inserts amusing vignettes into her flow of images and edits the footage in such a way that realistic images are defamiliarised and turned into something different and new. Effects of collage are used to make the audience laugh as well as to make them think about their own experience of ‘holidays at the seaside’ or their aspiration to some. However small the experience may be, like the itchiness of a hand-knit swimsuit, the oiliness of sun lotion or the warmth of the sun after a swim, they are all ways to connect the spectator, then and now, to the seasonal tourists of the Riviera. In Du Côté de la Côte, the questions ‘Qui sont-ils?’ and ‘Où sont-ils?’ (‘Who and where are they?’) are only rhetorical ones because Varda’s insistence on sensations keeps reminding us that we could very well be them. The film may lack the ‘interview’ dimension of other documentary projects like Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch’s Chronique d’un été/Chronicle of a Summer (1960), but an important portion of the film is dedicated to the daily sensory experiences of these people, to their longings and to their interactions with the sights and the locals. Through sensations and laughter, Varda tries to engage the spectator at a level other than purely intellectual. For instance, she enjoys pointing to the silliness and repetitive nature of routines and situations. Her deadpan comparison between the campers who are just as crammed in their respective lots as the occupants of the tombs in the nearby graveyard is a reminder of Varda’s unwavering wit. By giving attention to these excesses and at times irrational longings, she is turning the mirror towards both herself and ourselves and asking us to consider the question: what sort of tourists would we be? There are many possibilities in the film since she is careful not to lump all vacationers into one single group. Her derision is equally divided between all groups as she flags the contrasts between the different types of people enjoying the Riviera. The rich tourists who are looking to buy or build the most delirious villas are just as comic as the working class tourists. When they are handing the keys of their fancy cars to the hotel doorman, they do look the part of success and wealth, but at the same time Varda often contrasts their swimming trunks, bare feet and nonchalant gait with the ceremonial elegance of the doorman. The juxtaposition of these vignettes makes it obvious that even if all these people share a common space for the holidays, they indeed live very different lives. What unites them is this particular place that they all seem to fantasise about and the sensual experiences of the beach and seaside.

Sunbathing on the Riviera; an example of Varda’s humorous collages

The emphasis on sensory experiences is not the only way that Varda connects with her spectators. Although the figure of the doorman underlines the different spheres that tourists occupy, it also makes reference to something that Varda and her audience have in common, their love of cinema. In the beginning of the sequence about doormen the camera focuses on their attention to their customers. It is their body language and gestures that we are invited to scrutinise: ‘Au baromètre de sa familiarité, on est quelqu’un ou pas’ (‘His friendliness indicates whether you’re a somebody or a nobody’). In this series of images, there is no way for us to really differentiate between the doormen, or to single one out. The second part of the sequence, however, is quite different as Varda’s zoom on the direct gaze and face of a Buster Keaton looka-like who is said to have been a doorman at the Grand Hotel in Cannes for twenty years suddenly takes us from reality to fiction and from the present to the past. As the camera slowly zooms out, the eeriness of the scene submerges the audience as they come face to face with a building site where the doorman continues to greet people in spite of the chaos around him. So where is the Grand Hotel? Does this place exist, is it an invention of Varda’s, or a real building renovated at the time she was filming? Originally built in 1863, soon after the boulevard de la Croisette, the Grand Hotel was torn down in 1957–58 before being rebuilt by its new owners. So what Varda does here is to show us that reality and fiction are never separate entities. The mythical palace of the Grand Hotel is a dream that is being re-built, echoes of the dream factory, i.e. cinema, can be found just around the corner in the flesh and all that the audience needs to engage with these images and ideas is to be both curious and open-minded. In Du Côté de la Côte, Varda goes well beyond ‘the spirit of old postcards found in a musty album’ (Gorbman 2012: 47) as space becomes an opportunity to tell stories, to introduce unexpected connections and to connect through sensory experiences with others. We are not presented with an emotional geography associated with a fictional character or the director’s alter ego, but instead, in this work, it is the fleeting impressions and vivid sensations associated with the Riviera that Varda is summoning up for us.

Cannes, its Grand Hotel, and one of its real (or imaginary) doorman?

This attention to sensations when examining the potentially conflicting perceptions associated with a specific place is a constant throughout Varda’s work, including her recent installations. So to round up this chapter on Varda’s poetics of space, I thought it would be informative to probe into three of her installations which deal one way or another with the beach and seaside: Ping Pong Tong et Camping, La Cabane de l’Échec and Dépôt de la cabane de pêcheur. The first two installations Ping Pong Tong et Camping and La Cabane de l’Échec were displayed in 2006 on the ground floor of the Fondation Cartier in Paris. Ping Pong Tong et Camping and Dépôt de la cabane de pêcheur were also exhibited together in ‘Y’a pas que la mer’ at the Musée Paul Valéry in 2012 and I will take into account as much as possible the respective scenography of these two exhibitions.

(B) Deambulations in the Space of Varda’s Installations

In her article on feminist beachscapes, Fiona Handyside analyses ‘the sheer multiplicity of connections Varda makes between different ideas, images and cinematic representations of the beach’ in Les Plages d’Agnès (2011: 86). In the two exhibitions mentioned earlier, the seaside is also a place where ideas and images can come into contact and give rise to unexpected results. Varda, who is ‘a flâneuse on a beachscape’ (2011: 87), enjoys surprising her audience with mental zig-zags and associated twists no doubt influenced by her passion for surrealism. The three seaside installations Ping Pong Tong et Camping, La Cabane de l’Échec and Dépôt de la cabane de pêcheur are quite different in the way they present beachscapes, but they all invite the visitors to step into an unconventional space where our senses are brought to the fore.

La Cabane de l’Échec, later modified and renamed La Cabane du Cinéma (2009–10) for the Biennale de Lyon, was made of two separate elements in Paris. On the one hand, Varda and Christophe Vallaux had conceived a shack inspired by the temporary huts erected in Noirmoutier and along the coast, often made with pieces of wood, metal and discarded material. On the other hand next to this ‘hut of failure’ made of a metal structure covered with old film strips from the commercial copies of Varda’s unsuccessful Les Créatures, stands a professional mixing table projecting an inverted copy of the film. The hut is big enough for several people to stand in, and with its walls permeable to light, it looks like a rudimentary miniature of the bigger and glass-filled room where it stands in the Fondation Cartier. In both the exhibition’s catalogue and on the description of the installation, Varda emphasises the commercial failure of Les Créatures, the fact that it was shot in Noirmoutier (partly in her house, a restored windmill), and the famous actors involved in the project: Michel Piccoli and Catherine Deneuve. In doing so, she anchors this fragile edifice in the island of Noirmoutier (l’île in L’Île et Elle) and connects these artefacts with the career of her actors and the cultural memory and capital that goes with it. What should be pointed out in relation to the concept of a poetics of space is the director’s experimental play in this installation with light, scale and time. This architectural structure made of recycled film is a sculpture of light, a frame where strips of ageing 35mm celluloid, now greyish and red, echo the sheets of metal covered with rust. The capture of light and movement on film is arguably the essence of cinema, so that when Varda plays with light and perception here, she is going back in time and questions what one sees when watching a film in normal conditions versus non-traditional ones. The premise of this installation is the same as René Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), a film meant to underline the idea of threshold (between the stage of the theatre empty of its dancers during the intermission and the spectators) and of dynamic inversion.11 The light shining through stained glass windows in churches is supposed to encourage contemplation and meditation, and here visitors can take advantage of the static nature of images (and of the relative silence) to come as close as technicians do to the celluloid material of the film. Piccoli and Deneuve are recognisable icons of French cinema, young and famous but also small and partly visible because of the decaying film, their real strength being the fascination they hold for film-lovers.12 The visitors have a participatory role in observing the installation, they can move around and out of the hut, go back at their own leisure and even watch the film’s topsy turvy and at times comical footage. Cinema as an artistic medium has changed; moving from the analogue to the digital world. The mixing table nearby could very well become a relic, the trace of a different time and a proof that technological changes can impact our perception. Freed from the constraints of traditional screening, the reels of film become a material in their own right like wood and metal, which can be manipulated at will.

Varda’s ingenious recycling shows that they are neither lost nor useless since they become a self-referential and malleable material. The visitors’ experience certainly differs from that of Varda who was personally involved in the making of the film (the possessive ‘ma cabane de l’échec’, ‘my hut of failure’, is significant here). But the installation as a whole is a reflection on memory and on what we can (and cannot) share as spectators in the time we have together, and what remains and changes after we have parted. The temporary nature of any screening, the vintage character of the table and Varda’s experimentations throughout L’Île et Elle with photography, cinema and sound show that she wants to explore the new encounters that can occur in and out of the gallery with people who are willing to embrace this tribute to her work. Chamarette explains that ‘Through filming, refilming, exhibiting and re-exhibiting, mourning becomes a dynamic and recuperative gesture between film, filmmaker, exhibition space and viewer’ (2011: 45). I would add that the spectator’s mobility and sensory engagement in space necessarily needs to be considered to understand Varda’s practice as a site of resistance and creativity. If La Cabane de l’Échec is moving, it is not only because we feel part of a community of strangers, but because it makes us realise that our bodies (and minds) are intertwined in time and space alongside those of others. Varda’s cinematic promenades can only be effective if they take visitors on a challenging walk through memory and space.

The colourful set up of Ping Pong Tong et Camping in Sète (photo taken in April 2012)

The second installation I want to turn my attention to is Ping Pong Tong et Camping which, like Du Côté de la Côte, is unapologetically colourful and exuberant. In ‘Spatial and Emotional Limits in Installation Art: Agnès Varda’s L’Île et Elle’, Jordan accurately describes the cornucopia of sounds and colours that the visitors face when they encounter this ‘jubilant study in fluorescence […] framed by stacks of bright plastic buckets, jugs, bags, and colanders’ (2009: 583). In between the two symmetrical columns of buckets and jugs and the garish plastic curtains which make this space feel a bit more enclosed, there are two pseudo-screens. On the left hand side of the wall, a six-minute film which shows close-ups of children’s bodies as they play is projected on an inflated mattress, while on the right a child’s buoy serves as a second lower frame within which is projected a sequence of elaborate still images of flip-flops. In front of these two screening surfaces, there are five colourful deck chairs waiting for visitors to take place.13 The soundtrack that accompanies this piece is rhythmic and joyful and includes electronic noises, piano scales and the noise of children playing and shouting in the distance. This collection of sounds semi-orchestrated by Bernard Lubat is meant to summon the joyful mood associated with the camping site of the title.14 The soundtrack as a whole is fabricated in such a way that it invites the visitors to consider what they hear as an evocative soundscape for the whole installation rather than as a narratively-driven score matching the video projected on the mattress. The scenography of Ping Pong Tong et Camping evokes a camping site or a family’s spot on the beach, left empty as its occupants have gone for a swim. The double screen, which looks as if one is for the grown-ups and one for the children, is reminiscent of the family slide-show often organised after a holiday, a ceremony as important as the siesta (or quiet time) that Varda’s camera captured in the camping sites of the Riviera in Du Côté de la Côte.

On the slide show and video here, one element is particularly important: there are no visible faces and therefore no way for the visitor to identify a particular participant. Our attention is firmly directed towards the ping pong balls and colourful clothes and buckets, as well as on the actions and gestures that we see. Varda has taken the definition of camping that she provided in Du Côté de la Côte as ‘the airiest form of freedom’ and turned it into an installation inviting the visitors to engage with the objects and sounds meant to summon the joy and freedom experienced at the seaside.15 The profusion of plastic, a cheap material par excellence, may make the installation look like an endlessly recyclable scenography, but the carefully placed chairs and garlands of flip-flops and the attention to detail testifies to the elaborate process that has gone into organising this farandole of colours and sounds. This evocation of how vacationers spend their everyday also shows ‘the subtle beauty of both the mundane and the commodity’ (Chamarette 2012: 123). But are these objects speaking any real truth or is this installation a beautified fantasy? The flimsy quality of the plastic and the slide show of unconventional photographic still lifes remind us that holidays are only a temporary parenthesis, and that we are viewing a carefully prepared installation in a space with conventions different from those of the space it represents. The preparatory sketch included in the exhibition catalogue for Sète and the press kit for Paris highlight the development of the project. The reproduction of the compositions projected on the buoy are also telling. Flowers and fruits, classic elements in still life, are used as a background for the flip flop(s). Varda’s interpretation is both topical and comical as she chooses a form of art traditionally considered lower (yet popular) and uses round and oblong shapes (with olives, peas, cherry tomatoes and tulips) to reproduce the round frame of the buoy. These still lifes are also subtle memento mori or ‘reminders of death’ meant to underscore the joyful yet transient character of life.

In the Musée Paul Valéry, Ping Pong Tong et Camping was fittingly installed at the very end of the exhibition next to the glass cases holding traces of Varda’s epistolary exchanges with the late local painter Pierre François. Varda’s description of these objects from their personal collections: ‘un plaisir des yeux, un sourire qui virevolte en couleurs, des moments sporadiques de contacts’ (‘a visual feast, a colourful and twirling smile, sporadic moments of contact’) could equally be applied to Ping Pong Tong et Camping. Varda calls attention to the transient nature of the experience of the beach while emphasising its sensory dimensions. The holidays and their freedom may be an illusory respite but they offer endless material for a comical and sensory re-appropriation. One could speculate as to how viewers feel when required to engage with such a space after they have seen the darker and more contemplative Les Veuves de Noimoutier and Dépôt de la cabane de pêcheur. Contrary to the Fondation Cartier where these pieces were on different floors, the path that we have to take as a visitor in Sète is undeniably finishing on a more positive if not upbeat note with Ping Pong Tong et Camping.

Despite the title of the exhibition in Sète: ‘Y’a pas que la mer!’ (which literally means ‘There is much more than the sea’), the beach constitutes a recurrent presence in Varda’s work.16 In her provocative Dépôt de la cabane de pêcheur (2010), Varda’s vision of the beach is quite different from the colourful vision she elaborates in Ping Pong Tong et Camping. This is proof that the beach, like other spaces that Varda uses, is a highly malleable starting point to play with, an opportunity to engage with the set of stereotypical images associated with a place, and a chance to defeat her audience’s expectations and preconceptions. The ‘cabane’ of the title here (the hut) is not a refuge and looks open to the elements and the potential fury of the sea. To see this piece the visitor needs to enter a separate room, as a wall isolates it from the rest of the gallery; there is, so to speak, a threshold to cross to encounter this installation. Upon entering, one soon realises that this seaside scene is meant to feel different because the room is not only much darker, but also strewn with disparate objects often piled against each other including fishing nets, plastic and wooden crates, ropes, life buoys, rusted sheet metal, large wooden sticks and tarpaulins. This is not a touristy place, but a working shipyard or a harbour that may have been abandoned. The wall in front of the visitor where a looped video is screened is not flat but obstructed by rods and its double angle makes the video look oddly segmented. Against the opposite wall, visitors can sit or lean for a moment on a small pile of crates covered by a cushion or on a couple of basic beach folding chairs. The video entitled ‘La Mer Méditerranée avec 2 r et 1 n’ is a rollercoaster in terms of content and rhythm. It starts on a quiet beach, with the camera embracing the horizon as well as a group of random-looking walkers. On the left hand side, we see a long line of poles planted in the sand, symmetrical and graphic. On the right hand side, there is a (blue) screen in the shape of a sign where various images (including some of the same beach empty) are screened. In between these two, the walkers move away or towards us. The video incorporates scenes from Varda’s filmography like the naked lovers embracing in a hammock on a beach and the gigantic whale that Varda had built for Les Plages d’Agnès.

What is striking in ‘La Mer Méditerranée avec 2 r et 1 n’ beyond Varda’s use of her work as an endless source of striking audio-visual fragments is that the segments on the beach are contrasted with a mismatch of mostly amateur documentary footage, of the kind weather and news channels use to testify of the strength and horror of natural disasters and human conflicts. This section which immediately follows a close up on the giant whale and its scary stone head is frontal, violent, and surprising especially if one knows that Varda has a very strong fear of violence (see Varda and Adler 2010). Its editing to a sonic crescendo, and the poor quality of most of the images makes it hard to know what is really going on; in successive waves, we see fires, tsunamis, tanks, vehicles and bodies flicked away like grains of sand, and everywhere destruction and distress. After this short yet intense interlude, we go back to the calm lapping of the waves, to the poles on the same beach and to the walkers. The main difference with the first segment is that apart from the father carrying his young daughter in his arms, all the people we see, once they have walked past the screen, give the spectators a wave and are shown in close up on the blue screen in the right hand side of the wall we are facing. This acknowledgement by a gesture or a direct gaze of our position as a witness and onlooker is reminding us of our own position: we are in a comfortable gallery enjoying an artistic installation in a protected environment. This mise en abyme adds to the layers of meaning and does not obscure our understanding of the piece.

The multiple screens and fragmentary nature of this video and its mysterious nature attest that Varda is fully aware of the imperfect nature of any representational attempt. ‘Varda has no illusion about the limits of representation, but she plays with 3D possibilities to destabilize viewers, in and out of the comfort zone of their viewing practices in art spaces’ (Barnet 2011: 104). She knows that our time and space cannot, at the moment that we are experiencing this piece, match the confusion and despair that characterise the documentary footage that she has pieced together. This oscillation then between love, hope and beauty and the distressing admission that the world is not well is what makes this piece particularly effective. In a way, this installation is like an essay on the powerful nature of art. As in many of Varda’s works, her motto here could be summarised as: take a space, build up mental associations, refuse romanticising clichés and confront the audience by forcing them to engage with what they see, what they hear and what they feel. Contrary to the melancholy ending of Du Côté de la Côte, the part of ‘La Mer Méditerranée avec 2 r et 1 n’ that addresses our place within this elaborate artistic installation shows us that if there is only one thing that is still possible in the face of chaos, it is human connection. The cheeky goodbyes or hellos that the participants are sending us are proof of the fragile yet potentially significant connections that we can establish with others. The visual and material chaos in this hut and on the looped video and the fleeting emotions we are invited to experience are conceived as complementary rather than incompatible. What the artist decides to leave us with is the sense that in an age of ubiquitous visibility, images of human connections are still worth seeing and contemplating. While in cinema, space often explains or confirms the psychology of a fictional character, in installations as well as in unconventional works like ‘La Mer Méditerranée avec 2 r et 1 n’, Du Côté de la Côte, and L’Opéra Mouffe, it serves a different purpose. Space is a creative crossroad, a potentially endless source of connections and an opportunity of being with and feeling with others.17

1 In the alphabet book section of the volume she published on the occasion of her retrospective at the Cinémathèque française, she devotes a section to Bachelard which reads: ‘L’épistémologie n’atteignait pas ma compréhension mais il parlait de beaucoup d’autres choses, de Jonas par exemple bien installé dans sa baleine, ou des maisons depuis la cave humide jusqu’aux greniers qui sentent la pomme’ (‘I did not understand epistemology but Bachelard was talking about a lot of other things. He talked about Jonas, for instance, and his comfortable set up in the whale and about houses which smelled of apples from their humid basement to the attic’) (Varda 1994: 11).

2 Antoine Boursellier who plays Antoine in this film is the father of Varda’s older daughter Rosalie. He played in L’Opéra Mouffe in 1958 and was an active theatre actor and director until he died in May 2013.

3 For more detailed and enlightening readings of Cléo’s journey, see Jim Morissey’s ‘Paris and voyages of self-discovery’ (2008: 99–110) and Valerie Orpen’s excellent Cléo de 5 à 7 (2007).

5 I am copying here the whole poem from the book Médieuses to enable readers to get a sense of the text as a whole: ‘Chargée, De fruits légers aux lèvres, Parée, De mille fleurs variées, Glorieuse, Dans les bras du soleil, Heureuse, D’un oiseau familier, Ravie, D’une goutte de pluie, Plus belle, Que le ciel du matin, Fidèle, Je parle d’un jardin, Je rêve, Mais j’aime justement.’

6 ‘Le prologue, mettant en place un réseau de miroirs déroulant une série infinie de points de vue […] souligne que le portrait est ici en creux, dissimulant toujours ce qu’il révèle en portant l’attention non sur une identité, mais sur ce avec quoi elle est en relation, donc en transformation’ (‘The prologue with its ensemble of mirrors creating an infinite number of viewpoints […] emphasizes the fact that we are watching an “anti-portrait” which reveals as much as it hides and which focuses not on Varda’s rigidly fixed identity but on what her identity is connected to and on how it changes’) (Kausch 2008: 15).

7 There are two voice-over narrators in Du Côté de la Côte: one female and one male who take on different roles as the film progresses. This is why it is important to specify who is saying what at all times.

8 Claudia Gorman in her analysis of Varda’s early travelogues underlines the significance of this choice as well: ‘At the very opposite end of the scale from cinéma-vérité, which purports to give unmediated images of brute reality, O Saisons ô Châteaux and Du Côté de la côte arrange, reframe, and frankly denature any preconceived notions of their subjects’ (2012: 56).

9 It is interesting to note that this is very similar to the way Varda proceeds in Mur, Murs twenty years later when she uses a male whisperer to associate her images of murals with their title and creators.

10 The first time that the Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française (ORTF) broadcast something in colour was in 1957 and as time went on they looked for more and more programmes in colour and developed some in their studios of the Buttes-Chaumont. On the website of Varda’s production company, one learns that Du Côté de la Côte was used as a film-test screened on television daily for two months. http://www.cine-tamaris.com/films/du-cote-de-la-cote (accessed February 2013).

11 Entr’acte is a classic of avant garde cinema. It was commissioned by the Ballets Suédois’s director Francis Picabia who wanted an intermission for the ballet Relâche (1924). Its orchestral score composed by Erik Satie and loose narrative thread underscore and test the potentialities of the cinematographic medium and remind us today of the exciting adventures of the Dada movement in Paris at the time.

12 Piccoli was a household name even before he acted alongside Brigitte Bardot in 1963 in Le Mépris (1963), one of Godard’s most famous films. As for Deneuve, she had played in Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964) and many other memorable films including Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1964).

13 Interestingly enough, on the day I visited the exhibition in Sète, I noticed that while many visitors took the time to sit down and pause in front of the other installations where sitting was provided (in the shape of a chair or a bench) only children dared to use the deckchairs, often comparing the answers they had given to the quiz provided as a guide for the exhibition and chatting about what they had seen before their parents caught up and shooed them off.

14 I use the term ‘semi-orchestrate’ because the composition is a real team effort. Varda was inspired when she saw him play his ‘musical table’ and asked him to take part with this unusual instrument. The footage of the recording in Uzeste, however, makes it clear that even while she is shooting his hands tapping away, Varda is also indicating her approval and encouraging him, with two assistants throwing balls when she gestures them too. A partial clip of this happening can be found online at the following address: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x80ji1_bernard-lubatagnes-varda-uzeste_creation#.UVkeKhysiSo (accessed March 2013).

15 In Du Côté de la côte, Varda’s allusion to camping as the ultimate form of freedom is quickly overturned, however, when the overcrowded sites full of happy folks are compared with the campgrounds of happy dead who have also been attracted by the peaceful shores of the Mediterranean: ‘Le camping étant la forme la plus aérée de liberté et de cérémonial, […] ces camps surpeuplés de bon-vivants qu’attire ce rivage latin préfigurent bien les camps de très bons morts que ce rivage appelle.’ (‘Camping is the airiest form of freedom […] campgrounds crowded with happy folks attracted by the shore mirror the campgrounds of happy deads on the same peaceful shores.’)

16 Fiona Handyside’s article on the beachscapes in the work of three important female directors, including Varda, testifies to the need to analyse space in cinema in a way that incorporates more options than the simple dichotomies between urban and rural locations.

17 For an illuminating take on Varda’s attempts at being-with in Jacquot de Nantes (1990), see Laura McMahon’s discussion (2012: 15–20).