The Donkey and the Minaret

Francesco Crispi’s ‘youthful passion for freeing Italians from the empire of Austria matured as a passion for saving Africans from the empire of France and subjecting them to that of Italy.’

Leonard Woolf, Empire & Commerce in Africa: A Study In Economic Imperialism1

‘I think that the constant study of maps is apt to disturb men’s reasoning powers.’

The Marquess of Salisbury, House of Lords, 10 July 1890.

Lady Gwendolen Cecil, Life of Robert Marquis of Salisbury, Volume IV 1887-18922

‘Italy appears to have gone to war with Turkey and to have occupied Tripoli and Benghazi.

Extraordinary piratical business.’

C E Callwell, Field-Marshall Sir Henry Wilson: His Life and Diaries, Volume I3

CESARE Balbo, who anticipated the future of Italy as a confederation of separate states led by Piedmont-Sardinia, had written in 1844:

Italy, as soon as she is independent […] will have in turn to think of that need of expansion, of expansion eastwards and southwards […] Then, Naples […] will be called upon to play the first part in this work of external expansion. Whether it be to Tunis, or to Tripoli, or to an island […] matters not.4

Giuseppe Mazzini had also continued this theme in his 1871 essay ‘Principles of International Politics’ arguing that ‘Italy was once the most powerful coloniser in the world.’5

Tunis, Tripoli, and the Cyrenaica belong to that part of Africa up to the Atlas Mountains that truly fits into the European system. […] Already in the past, the flag of Rome was unfurled on top of the Atlas Mountains, after Carthage had been vanquished, and the Mediterranean became known as Mare nostrum. We were the masters of that entire region until the fifth century. Today the French covet it and they will soon have it if we don’t get there first.6

Italy failed to get to Tunis first, leaving only Tripolitania and Cyrenaica as potential Italian territory. To Italian nationalists these areas had much to commend them, being close to Italy with a geographic position that promised strategic value. One Cyrenaican port, Tobruk, possessed one of the finest natural harbours along the entire coast. The Tripoli vilayet had also, as Mazzini stated, been a part of the Roman Empire from the first century BC until its loss in the fifth century AD, and this counted for much amongst those who thought of fulfilling the long standing patriotic dream of building a Third Roman Empire.7

Indeed, though there was no ‘master plan’ as such for taking possession of Tripoli, it is unarguable that the ground, as it were, was well prepared for such an undertaking. The other members of the Triple Alliance were the first to be squared, at least formally, with the renewal of that Alliance in 1891. At that time a separate treaty was negotiated with Germany under the auspices of that renewal, Article IX of which stated:

Germany and Italy engage to exert themselves for the maintenance of the territorial status quo in the North African regions on the Mediterranean, to wit, Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, and Tunisia. The Representatives of the two powers in these regions shall be instructed to put themselves into the closest intimacy of mutual communication and assistance. If unfortunately, as a result of a mature examination of the situation, Germany and Italy should both recognize that the maintenance of the status quo had become impossible, Germany engages, after a formal and previous agreement, to support Italy in any action in the form of occupation or other taking of guaranty which the latter should undertake in these same regions with a view to an interest of equilibrium and of legitimate compensation. It is understood that in such an eventuality the two Powers would seek to place themselves likewise in agreement with England.8

During the negotiations for the fourth renewal of the Alliance, in 1902, Italy managed to gain Austro-Hungarian approval of its position vis-à-vis Tripoli. This was not expressed via the text of the treaty, which remained the same as that of 1891. However, on 30 June 1902 the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador to Rome, Baron Marias Pasetti, wrote an official declaration to the Italian Government, setting out his government’s position. This document was to be ‘secret’ and would be ‘produced only in virtue of a previous agreement between the two Governments.’

I the undersigned, Ambassador of His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty, have been authorized to declare to the Government of His Majesty the King of Italy, that, while desiring the maintenance of the territorial status quo in the Orient, the Austro-Hungarian government, having no special interest to safeguard in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, has decided to undertake nothing which might interfere with the action of Italy, in case, as a result of fortuitous circumstances, the state of things now prevailing in those regions should undergo any change whatsoever and should oblige the [Italian] Government to have recourse to measures, which would be dictated to it by its own interests.9

Having asked for and gained these gestures of highly qualified approval from formal allies, approaches were made to Britain and France in search of something similar. In 1900 an exchange of letters between the Italian Foreign Minister and the French ambassador was initiated. The thrust of this correspondence was that Italy would, diplomatically, give France a free hand in Morocco in exchange for a reciprocal arrangement vis-à-vis Italy and Tripoli. This exchange was symptomatic of a more general rapprochement between the two states. Indeed, it was obvious from this point on that Italy’s involvement in the Triple Alliance was somewhat tenuous. As Andre Tardieu, who later served as Prime Minister of France on three occasions, put it in his 1908 book: ‘Since the rapprochement, the Triple Alliance has lost its edge.’10

The new friendship between France and Italy was notable in several contexts. On 8 April 1901 an Italian squadron under the command of Prince Tommaso, the Duke of Genoa and uncle of Victor Emmanuel III, arrived at Toulon on an official five-day visit. The Duke met with Emile Loubet, the French president, and invested him with Italy’s highest decoration, the Collar of the Annunciation.11 The relationship between the two states deepened. Victor Emmanuel III was feted at Paris during a state visit on 14 October 1903, and at the conclusion of a banquet at held at the Elysée Palace, Loubet commented on the significance of the visit as demonstrating:

[…] the close agreement which, responding equally to the sentiments and interests of the Italian and French peoples, has been established between their Governments. It is assured that the two countries can pursue their national tasks with reciprocal confidence and goodwill.12

The following March the visit was reciprocated, an event that greatly upset the Pope, Pius X, who, because he was ignored, saw it as a provocation.13 The Pope was not alone in feeling discomfited by the Franco-Italian rapprochement. Italy’s allies were also troubled. Count Karl von Wedel, Ambassador at Rome for the German Empire enunciated some of these worries in a letter written to Friedrich von Holstein, the ‘grey eminence’ who headed the political department of the Foreign Office, on the final day of the Toulon naval visit:

The festivities in Toulon are today happily reaching their end, after having finally after all exceeded the limits of a simple exchange of courtesies. This was to be expected. What causes me most concern in all this is the undoubtedly increasing megalomania in certain Italian circles. France’s wooing strengthens the Italians’ consciousness of their own importance and of the great value of Italian friendship.14

Despite the obvious, and continually improving, diplomatic relationship with France, the Italian foreign office nevertheless continued to insist to Germany and Austria-Hungary of the centrality of the Triple Alliance in Italian Foreign policy.15

The symbolic manifestations of Franco-Italian cooperation and friendship were underpinned however by rather more concrete results, such as the mutual abandonment of the concentration of military forces on the Franco-Italian frontier.16 In the colonial context, the rapprochement culminated in an exchange of notes during July 1902 whereby it was agreed:

[…] that each of the two powers can freely develop its sphere of influence in the above mentioned regions [Tripoli and Morocco] at the moment it deems opportune, and without the action of one of them being necessarily subordinated to that of the other […]17

Italy also recognized at this time a settlement over the borders of Tripoli and Chad (later, from 1910, French Equatorial Africa) that had been agreed under an Anglo-French convention of 14 June 1898, which delineated British and French spheres of influence east of the Niger River. Further to this, a joint declaration of 21 March 1899 stated that the French zone started from the point of intersection of the Tropic of Cancer with the 16th degree of longitude and then ran south east until it met the 24th degree of longitude (the latter not determined until 1919).18

This proprietorial interest in the international border of a territory that, formally and legally, had nothing to do with Italy was not a novel phenomenon. In December 1887 Italy had reacted with indignation to a report in that month’s Bulletin de la Société de Géographie announcing that an agreement had been reached between the Ottoman Empire and France regarding the border between Tunis and Tripoli. What particularly aroused the ire of the Italian foreign office and government was the supposed shift of the border, as it touched the Mediterranean coastline, eastwards by some thirty-two kilometres. The Italian Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Baron Alberto de Blanc, was ordered as a matter of urgency to seek an audience with the Ottoman government, in order to clarify, and if necessary to protest regarding, the matter. He was assured, both by the Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) and the Sultan, that there was no such agreement.19 Indeed, real or imagined disputes with France regarding the Tunis-Tripoli border were to be a recurring theme in Franco-Italian relations right up to the time of the relaxation of tensions.

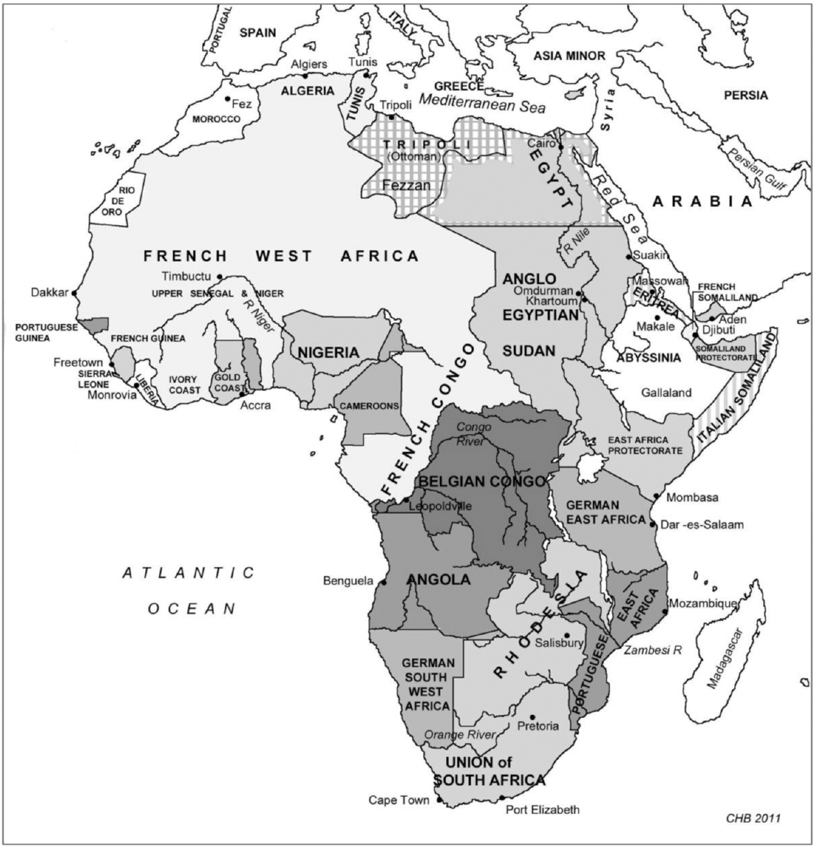

Africa in 1911, showing the colonial possessions of the various powers. Many of the territories bordering the Mediterranean and Red Sea were nominally Ottoman, but only Tripoli (roughly modern-day Libya) was not under European domination of one kind or another. In the entire continent, only Liberia and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) were independent. (© Charles Blackwood).

It can be reasonably argued then that, by the early years of the twentieth century if not before, it had become an article of faith, perhaps even an idée-fixe in foreign policy terms, amongst important sections of the Italian political class at least, that Tripoli was destined to become Italian territory. The Italians hoped that under their management the country, which had had a reputation for great productivity in ancient times, might become once more a garden. Perhaps most importantly of all, it was the only area on the southern Mediterranean littoral to which Italy could aspire without coming into conflict with the interests of England or France. Indeed, it is hardly an exaggeration to say that it became axiomatic to any Italian government, no matter what its political complexion, that Tripoli was a ‘promised land’ that would some day belong to Italy.

This was a matter that was not just confined to the political right. On 13 April 1902, the journalist Andrea Torre published in Giornale d’Italia an interview he had conducted with Antonio Labriola, the ‘father of Italian Marxism.’20 Labriola was a theoretician whose 1896 Essays on the Materialist Conception of History have been described as soon becoming ‘a classic in European Marxist literature,’ whilst their author is considered as being a forerunner of Gramsci in formulating the concept of neo-Marxism.21 Trotsky also described Labriola’s writings, which he had read in their French translation, as having influenced him.22

During the course of the interview Torre asked Labriola about the usefulness of Italian expansionism into Tripoli, and if he, and socialism generally, would be opposed to it. Labriola replied that socialist interests couldn’t be opposed to national interests; indeed they must promote it in all its forms.23 This coincidence of interests came about because Labriola visualised Tripoli under Italian occupation or control as an outlet, a destination, for Italian workers, who might otherwise emigrate to foreign countries and be lost to Italy thereafter.24 The latter opinion was optimistic; as an experienced reporter was later to put when the opportunity arose for Italians to actually live in Tripoli: ‘No Italian emigrant will go [to Tripoli], so long as there is such a place as Chicago.’25 Labriola the theoretician was to be proven rather too cerebral in his general thesis also; most Italian socialists were to prove violently opposed to Tripolitanian colonialism.

Internationally, the UK, the power with the longest standing modern commitment to, and interest in, stability vis-à-vis the Mediterranean, would also have to be squared. British sea power in the area was centred on Malta, a strategically vital point so situated as to be able, especially with a powerful fleet based there, to control communication between the eastern and western Mediterranean. The sea route through the Mediterranean was, even before the advent of the Suez Canal exponentially increased its importance, a vital imperial artery to India and Britain’s far eastern possessions and territories. Prior to the construction of the canal, the journey to India via the Mediterranean had involved disembarking on the Syrian coast and travelling overland through Mesopotamia to the Persian Gulf before boarding ship again. The land portion of the journey was then one through Ottoman-controlled territory and was thus dependant upon Ottoman goodwill and stability, neither of which could be considered reliable or eternal. The more secure sea route involved an immense voyage via the Cape of Good Hope. Accordingly, following the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, albeit that Egypt was nominally Ottoman territory, the Mediterranean sea-route, and thus the island of Malta, became of vital importance to the British Empire.26 It naturally followed that Malta then became the base for the largest and most powerful Royal Navy fleet, comprised of the most modern ships.27

This was to change however; as Admiral Sir John Fisher, who had become First Sea Lord in 1904 and remained in the post until the beginning of 1910, put it in 1906:

Our only probable enemy is Germany. Germany keeps her whole Fleet always concentrated within a few hours of England. We must therefore keep a Fleet twice as powerful concentrated within a few hours of Germany.28

This strategic realignment was, as is well known, brought about by the contemporaneous Anglo-German naval race. Despite the downgrading of the Mediterranean, the British Admiralty still retained powerful forces there; the core of the fleet in 1907 comprised six (pre-Dreadnought) battleships.29 These forces were gradually withdrawn, the French Navy concentrating its fleet there whilst the British concentrated in the North Sea. However, the Royal Navy, which held that dependence upon the French fleet was ‘unpalatable’, still possessed the ability to send heavy units there if required.30 The 1912-13 deployment of battle-cruisers is evidence of this.31

Since Malta and the Royal Navy also sat athwart the north-south sea-lanes between Italy and Tripoli, it followed that any Italian intervention in the latter area would have to take place with at least the tacit agreement of the British government. This had been, at least to some extent, obtained in 1902 when Britain’s Lord Lansdowne, ‘the Foreign Secretary who abandoned isolation,’32 authored a note to his opposite number Guilio Prinetti:

His Britannic Majesty’s Government have no aggressive or ambitious designs in regard to Tripoli as above described; that they continue to be sincerely desirous of the status quo there, as in other parts of the coast of the Mediterranean and that if at any time an alteration of the status quo should take place it would be their object that, so far as is compatible with the obligations resulting from the Treaties which at present form part of the public law of Europe, such alteration should be in conformity with Italian interests. This assurance is given on the understanding and in full confidence that Italy on her part has not entered and will not enter into arrangements with other Powers in regard to this or other portions of the Mediterranean of a nature inimical to British interests.33

This and the other somewhat hazy and heavily qualified statements of support for Italian designs on Tripoli have been dismissed as agreements which, ‘the other Great Powers had simply signed to pacify Italy’s apparently insatiable appetite for verbal [sic] agreements which would never be acted on.’34 While this is a statement that is difficult to controvert, there seems little doubt that they were taken seriously by Italian politicians. For example, Prinetti’s successor but one, Tommaso Tittoni, was called upon to elucidate Italian foreign policy in respect of Tripoli in the Senate on 10 May 1905. He began by pointing out that he could not detail all the various understandings reached with other states regarding the matter:

If the necessary reserve incumbent upon the Government forbids me from speaking of the single acts by which all the interested Powers have recognized Italy’s prior rights on Tripoli as before those of any other nation, nothing prevents my saying that these rights have been assured in the most explicit and efficient manner.35

He went on to make clear that, at least at the present time, these ‘rights’ so assured did not translate into the physical occupation of the territory. He did however leave open the question as to whether this might occur in the future:

[…] To my mind Italy should not occupy Tripoli except when circumstances will make such a course absolutely indispensable. In Tripolitania Italy finds the element which determines the balance of influence in the Mediterranean, and we could never allow this balance to be disturbed to our damage.36

Though couched in diplomatic terms, Tittoni was telling the senate that as long as no other power gained any territory in the Mediterranean, then he saw no reason for Italy to take formal control of Tripoli. He went on to point out that this did not mean that Italian influence there should be neglected:

But, if we do not wish to occupy Tripoli at present, that does not mean that our action there should be nil. It is evident that the rights we have upon Tripoli for the future must give us, even at present, a preference in the economic field, in directing our capitals to that region and in promoting commercial currents and agrarian and industrial enterprises. We count upon doing this with the full consent of the Sublime Porte,37 with which we are in the best relations, and which should have the greatest interest in facilitating Italy’s peaceful and civilizing action.38

Tittoni listed some aspects of this peaceful and civilizing action:

Italian importation in Tripolitania, which in 1899 amounted to 1,626,000 lire, today amounts to 2,618,000 lire. It is not much, but some progress has been made. In the same way the exportation from Tripoli to Italy has risen to 979,418 lire. The postal service has been better developed by us, also the Royal Schools, which have at present about eleven hundred pupils, and the subsidized ones two hundred. That these schools have had a useful effect is shown by the fact that in Tripolitania, after Arabic, Italian is the language which is most spoken, and it has become so necessary that also other nations have had to adopt it in their schools, because it is an indispensable instrument for whoever in that country wishes to employ his abilities under any form.39

The implication in the above statements was that if Italy’s economic interests in Tripoli were small, they were in any event secondary to political interests. Tittoni made this explicit in a debate in the Chamber of Deputies that took place over two days on 12-13 May1905.

[I]f Tripolitania may be for us of small economic value, it must not be forgotten that economic penetration in that region comes second to our political interest, and the latter, as every one recognizes, is of the very first importance.40

Nevertheless, as he had assured the Senate on 10 May, the ‘care of the Government’ was, at least for the moment, directed towards ‘our work of economic penetration in Tripolitania.’41

The most visible agent for economic penetration, also known as peaceful penetration (penetrazione pacifica), was the Bank of Rome (Banco di Roma). The bank was founded on 9 March 1880 by three aristocrats with close ties to the papacy, and remained rather parochial inasmuch as it largely confined its activities to Rome and the immediate area. In 1892 Ernesto Pacelli, members of whose family had been officials in the Papal States and who had refused to serve under the auspices of the Italian state, joined the bank, becoming president in 1903. Pacelli was the uncle of Eugenio Pacelli, who became the controversial Pope Pius XII in 1939, and was a close confidant of Pope Leo XIII. The latter entrusted him to a large degree with the papal finances and this injection of capital allowed the bank to expand its activities. However its close ties with the papacy, (it became known as ‘the bank of the Vatican’), made it an object of some suspicion vis-à-vis the Italian government.42 This estrangement, it has been claimed, was overcome by the expedient of co-opting Romolo Tittoni, the brother of the Foreign Minister, onto the board in 1904. This appointment also instigated a new policy, initiated by Tittoni, whereby, during a period of ‘frenetic expansion’ lasting around six years, the bank sought to expand and increase its presence ‘in the areas that international diplomacy had set aside for Italian control, in particular Libya.’43

By 1907 the bank had begun making investments in Tripoli, recruiting Enrico Bresciani, an Italian financier and businessman who had worked for several years in Somalia, as its local agent.44 Difficulties were encountered, inasmuch as Ottoman laws placed restrictions on foreign ownership of land and businesses. These were partially overcome by way of diplomatic pressure in the long term and, in the short, by purchasing an existing mercantile venture, complete with land, from the Arbib family of Tripoli; Jewish merchants with joint British-Italian nationality.45 This transaction was attended with some difficulty,46 but expansion was nevertheless rapid thereafter and the total value of the capital put into Tripoli by the Bank of Rome up to 1911 was about four to five million dollars. These involved ‘a whole series of the most diverse undertakings:’ a coastal shipping line, which linked various ports on the Tripolitanian coast, and businesses such as olive oil processing, flour milling, and alfa, or esparto, grass pressing – ‘largely exported to Great Britain for paper making.’47 Indeed, at the onset of the Banco di Roma’s interest in the area, processed esparto grass was Tripoli’s leading export commodity.48 By 1911 it owned ‘an enormous Esparto Grass mill, the most colossal building in all Tripolitania.’49

Expansion indeed seemed rapid; during its first year of operation the bank opened branches at Benghazi (Bengasi, Bingazi), Homs (Khoms), Zlitan (Zletin), Misurata (Misratah), Zawara (Zwara) and Derna.50 Despite it being illegal, the bank also began acquiring land, either through foreclosing on mortgages or via an agent. These private measures, as they might be termed, were paralleled; the Italian government established schools and post offices in the province. However, despite official encouragement few Italians were prepared to settle, or start businesses, there. This is perhaps unsurprising given the conditions. The American explorer and writer Charles Wellington Furlong visited the area in 1904-5 and later published his observations.51 According to him:

[…] the oasis of Tripoli, [is] a five-mile tongue of date-palms along the coast at the edge of the Desert. Under their protecting shade lie gardens and wells by which they are irrigated. In this oasis lies the town of Tripoli. It is beyond this oasis that the Turks object to any stranger passing lest he may be robbed or killed by scattered tribes, which the Turkish garrisons cannot well control.52

Tripoli is a land of contrasts – rains which turn the dry wadis [river beds] into raging torrents and cause the country to blossom over night, then month after month without a shower over the parched land; suffocating days and cool nights; full harvests one year, famine the next; without a breath of air, heat-saturated, yellow sand wastes bank against a sky of violet blue; then the terrific blast of the gibli, the south-east wind-storm, lifts the fine powdered desert sand in great whoofs of blinding orange, burying caravans and forcing the dwellers in towns to close their houses tightly.53

Through lack of rain the Tripolitan can count on only four good harvests out of ten. This also affects the wool production, and in bad years the Arab, fearing starvation, sells his flocks and his seed for anything he can get.54

The Scottish geographer and author Arthur Silva White had assessed the area some two decades previously, and his assessment shows that little had changed by the time of Furlong’s visit:55

[…] in Tripoli, along the remainder of the Mediterranean coast [from Tunisia] up to the Nile Delta, except in the peninsula of Barka [Cyrenaica] and the narrow coastal zone in its neighbourhood, we encounter a soil of almost universal barrenness, favourable for little else but the growth of marketable grasses, vegetables, and Tropical fruits. The steppes and deserts extend in many places right up to the sea, and are backed, at a very short distance inland, by stony plateaus. The terrible Libyan Desert itself advances to the coast-line and encroaches upon the Nile Delta.56

[…] the Turkish province of Tripoli is so barren that, beyond esparto grass, fruits and vegetables, its products are not at present of any considerable value. The port of Tripoli is, however, the terminus of the caravan-trade across the Sahara, and the oasis of Murzuk, in Fezzan, is another important trade-centre. Fez and Morocco city are other centres of the caravan-traffic of the Sahara, the principal ‘commodity’ of which would appear to be slaves.57

Furlong was of the opinion however that under a ‘Christian European power’ the introduction of the ‘artesian well’ would allow Tripoli to be ‘reclaimed from the desert.’58 Presumably the trade in slaves would have to be abandoned, but in any event the Bank of Rome lost heavily, suggesting, as one scholar has put it, that the ventures were essentially political in aim:

[…] neither well managed not necessarily conceived of as likely to be profitable in their own right; rather, it appears, that the directors hoped to receive subsidies and government financial business in exchange for promoting Italian interests in areas staked out for Italian colonization.’59

Indeed, it has been convincingly argued that the Bank of Rome was the Italian government’s ‘chosen instrument’ to carry out its policy of peaceful penetration. The intended aim of this policy being to create an increasing Italian presence in the area such as would eventually absorb Libya without the necessity of resorting to force.60 If this was indeed the policy of the Italian government, then it was a dismal failure. As Eugene A Staley put it:

The desert sands of Tripoli were not too enticing, however, and most of the ‘economic interests’ had to be created by the Banco di Roma. The Italian population of the whole region in 1911 was hardly a thousand, and scarcely two hundred of these had come from Italy.61

Nevertheless, the quest for diplomatic approval of Italy’s ‘rights’ continued, with the Russians being brought into the arena. Alexander Izvolsky, Russian Foreign Minister from 1906, engineered a royal visit by Nicholas II to Italy in October 1909. The Tsar met with King Victor Emmanuel III at the Castle of Racconigi, during which visit their respective foreign ministers Tittoni and Izvolsky concluded a secret agreement. Known in English as The Racconigi Bargain, the relevant article of this agreement stated that ‘Italy and Russia pledge themselves to regard with benevolence, the one Russia’s interests in the matter of the Straits [the Bosphorus and Dardanelles], the other Italian interests in Tripoli and Cyrenaica.’62 This ‘bargain’ was kept secret; the Russians failed to inform Britain and France and Italy likewise neglected Germany and Austria-Hungary.

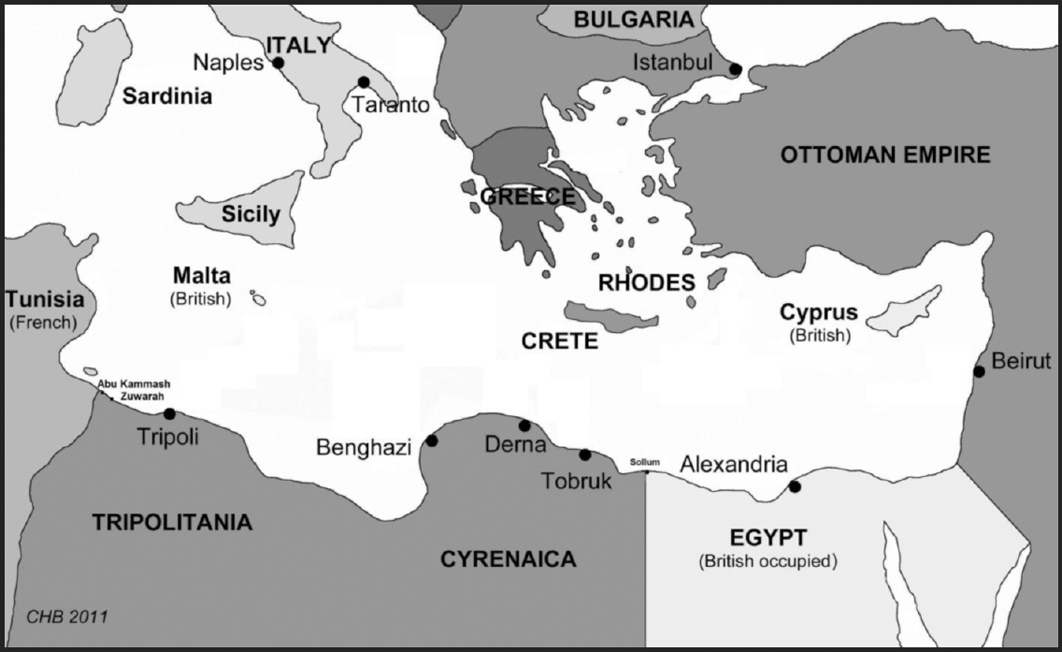

The Eastern Mediterranean. The borders between Egypt and Cyrenaica, and Tunisia and Tripolitania, were not well delineated beyond the coast, and not even there with any great exactitude. This was a matter of little import until the Italians occupied Tobruk and the British feared the creation of a naval base there, whereby Italy would be able to dominate the adjacent coastline and local sea area. This included the only other decent anchorage for several hundred kilometres at the Bay of Sollum. Accordingly, the logic went, if Italy had Tobruk then Britain, via Egypt, would have to have the use of Sollum. This small port was however garrisoned by the Ottomans. To the intense annoyance of Italy, Britain did not move to occupy Sollum until after it had negotiated the matter with the Ottoman government. France also took advantage, occupying the Oasis of Djanet in the far south-west of Fezzan. (© Charles Blackwood).

It is of course impossible to judge how the two strands of Italian policy, if it can be called that, towards Tripoli and the Ottoman Empire – the seeking of diplomatic acquiescence in terms of rights on the one hand and peaceful penetration on the other – would have played out had not there been a conjuncture of other factors.

The first of these was the ‘Young Turk’ revolution of 1908. The CUP proved keener to resist ‘peaceful penetration’ and this was given effect when a new Governor (vali) was appointed in October 1910. He quickly made his presence felt, as was made clear in a statement by Antonino Paternò-Castello, the Marquis of San Giuliano (marchese di San Giuliano) who had become Italy’s Foreign Minister on 1 April 1910. According to San Giuliano:

[…] the new Vali, Ibrahim Pasa, declared quite frankly […] that he would offer unceasing and systematic resistance against all Italian initiative, and he made it clearly understood that these were the instructions of his Government. Hence all Italian proposals and attempts to obtain concessions such as aqueducts, wireless installation, road-making, etc., were simply rejected. In defiance of our treaties the Turks hindered our subjects from acquiring land and from conducting any other similar operations. At Homs, Bengasi, and Derna the natives willing to sell land to the Italians were menaced, and revenge was taken under futile pretexts on those who disobeyed. Contrary to definite agreements, every possible obstacle was put in the way of our archaeological and mineralogical missions. The same opposition was raised against all other Italian enterprises, such as mills, oil-presses, and especially against our shipping. The terrorized natives, fearful of the revenge threatened, dare not avail themselves of any of our benevolent institutions or enterprises.63

Antonino Paternò-Castello, marchese di San Giuliano. The Italian Foreign Minister, Antonino Di San Giuliano, as he was more usually known, had the tricky diplomatic task of steering his and Giolitti’s foreign policy in respect of Tripoli and war with the Ottoman Empire between the competing interests and demands of the Great Powers, particularly as these related to the potentially unstable Balkan region and Ottoman rule there. Insisting that Italian policy was based on maintaining the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, whilst simultaneously waging war on it in order to force it to disgorge Tripoli, was a delicate business. (Author’s Collection).

This was of course provocation, or at least deemed so by Italy, but it did not necessarily constitute a case for war. What furthered that particular case at least to some extent was the more or less contemporaneous rise of a jingoistic movement that quickly gained popularity. This was the Italian Nationalist Association or ANI (Associazione Nazionale Italiana). Founded by nationalist writers Enrico Corradini and Luigi Federzoni at Florence in 1910, the organisation organised a vigorous pro-colonial policy, which it saw as only being realisable through war. Indeed, according to Corradini’s keynote speech to the three hundred delegates of the First Congress of the ANI in December 1910, war was a prerequisite for what he termed ‘national redemption:’

[…] there are proletarian nations as well as proletarian classes; that is to say there are nations whose living conditions are subject to great disadvantage, compared to the way of life of other nations, just as classes are. Once this is realised, nationalism must, above all, insist firmly on the truth: Italy is, materially and morally, a proletarian nation. What is more, she is proletarian at a period before her recovery. That is to say, before she is organised, at a period when she is still groping and weak. And being subjected to other nations, she is weak not in the strength of her people but in her strength as a nation. […] Nationalism […] must become, to use a rather strained comparison, our national socialism. That is to say that just as socialism taught the proletariat the value of the class struggle, we must teach Italy the value of the international class struggle. But international class struggle means war. Well, let it be war! And let nationalism arouse in Italy the will to win a war […] In a word, we propose a means of national redemption which we sum up in the expression ‘the need for war.’64

No great powers of perception are required to see great similarities between such utterances and those of a later era in Italian politics.65 Certainly many of the personalities associated with the ANI, including Corradini and Federzoni, were not disadvantaged during Mussolini’s regime.66 As per Corradini’s address, and as is now known to be a common tactic of jingoistic political movements, the ANI framed part of their appeal in terms of grievance. According to them Italy had suffered from humiliation in the past that needed to be avenged; events such as the ‘loss’ of Tunis to France and the defeat at Adowa were examples.67 Seizure of Tripoli would avenge the political loss of face vis-à-vis Tunis whilst the triumph of Italian arms would do likewise in respect of Adowa. That 1911 was the half-centenary of the founding of the Italian state was a matter also exploited, as was the long standing Italian ‘holy mission’ to acquire the area.68 The arguments, if they may be deemed such, of the ANI began to gain traction with the Italian public and, much more importantly, with the political class. A tipping point came when existing liberal and conservative parties agreed to adopt the nationalist position, and, aside from parliamentary pressure, organised grass-roots demonstrations in favour of war.69

The Italian government, from 30 March 1911 under Giovanni Giolitti for the fourth time, found itself in a political bind. On the one hand Giolitti was pledged to political reform, one of the main planks of which was a move towards universal manhood suffrage. On the other however, his government found itself on the wrong side of ‘public opinion’ when warning parliament that invading Tripoli, and thus violating Ottoman sovereignty, could well trigger a European war.70 It would also involve a complete volte-face in foreign policy. San Giuliano put it thus in June 1911: ‘Our policy, like that of the other Great Powers, had for its foundation the integrity of the Ottoman Empire.’71 There were further, domestic, problems occasioned by a weakening of the Italian economy, which caused problems with both industrialists and trade unions.72 Victor Emmanuel III signalled his affinity with the nationalist cause when he attended the Colonial Institute’s second Congress of Italians Abroad (Congresso degli Italiani all’ Estero) held in Rome during June 1911. Delegates from 84 cities in 22 countries attended the Congress, which deliberated issues concerned with Italian emigration. The predominant matter they concerned themselves with was however that of Tripoli. Federzoni put forward a resolution for energetic military action to guarantee Italian rights in the province, and this was approved unanimously.73 Ciro Paoletti has argued that ‘Gioletti did not like wars. He considered them useless, especially when it was possible to negotiate.’74 Indeed, Gioletti is reported as arguing that:

The integrity of what is left of the Ottoman Empire is one of the principles upon which is founded the equilibrium and peace of Europe […] And what if, after we attack Turkey, the Balkans move? And what if a Balkan war provokes a clash between the two groups of powers and a European war? Is it wise that we saddle ourselves with the responsibility for setting fire to the powder?75

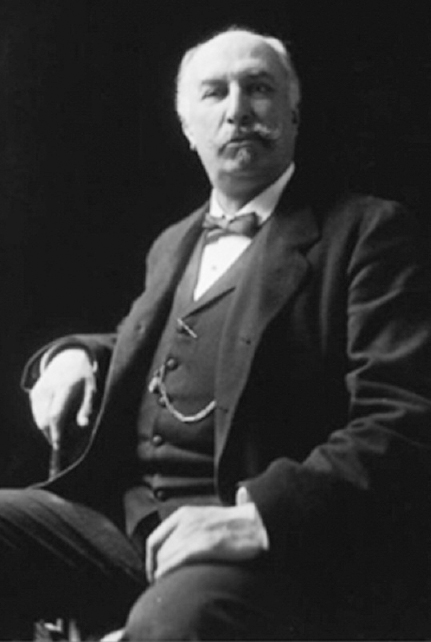

Giovanni Giolitti. The period 1901-14 in Italian political life came to be known as the ‘Giolittian era’ because of Giolitti’s domination of parliament and politics. During this period he was to be Prime Minister on three occasions – 1903-05, 1906-09, and 1911-14 having served in that position once before in 1892-93 (he attained the office once more in 1920 and retained it for some eleven months). During the period in question Giolitti’s governments sought to democratise Italy by extending the franchise and by introducing other liberal reforms such as old-age pensions. There were many opponents of these, and in order to survive and get them through parliament, Giolitti had to placate the right wing groupings there, the most powerful and certainly most vocal being the Associazione Nazionale Italiana. These were extreme nationalists who wanted a colonial empire, and he determined to give them one in the form of the Ottoman territory of Tripoli (Libya), the possession of which had long been an unredeemed Italian ideal. (Author’s Collection).

Nevertheless Bosworth posits that the circumstances the Giolitti government found itself in 1911 led it to believe that ‘a relatively cheap colonial war’ – social-imperialism; an attempt to focus the electorate on foreign policy rather than domestic issues – was a way out.76 Indeed Childs points out that he is ‘persuaded’ that it was the ANI and the press that provided the main domestic impetus for war.77

Perhaps the final factor in the mosaic of conjunction came with the actions of Italy’s ally Germany. The German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg had been pursuing a policy of détente with Britain, but this was damaged, by the Second Moroccan, or Agadir, Crisis, which occurred following the dispatch of a French military expedition to Fez, the Moroccan capital, on 11 May 1911 after an appeal for assistance from the ruling Sultan who was facing a rebellion.78 Though Germany had legitimate grounds for complaining of this action, which was undertaken without consultation, the German Foreign Minister, Alfred von Kiderlen-Wächter, saw it as an opportunity for scoring a foreign policy coup. Determined to back up diplomatic action with a touch of sabre rattling, he had the German warship Panther dispatched to Agadir to safeguard German ‘interests.’ He outlined his rationale in a memorandum of 3 May, before the French had moved:

The occupation of Fez would pave the way for the absorption of Morocco by France. We should gain nothing by protesting and it would mean a moral defeat hard to bear. We must therefore look for an objective for the ensuing negotiations, which shall induce the French to compensate us. If the French, out of ‘anxiety’ for their compatriots, settle themselves at Fez, it is our right, too, to protect our compatriots in danger. We have large firms at Mogador and Agadir. German ships could go to those ports to protect the firms. They could remain anchored there quite peacefully – merely with the idea of preventing other Powers from intruding […] The importance of choosing those ports, the great distance of which from the Mediterranean should make it unlikely that England would raise objections, lies in the fact that they possess a very fertile hinterland, which ought to contain important mineral wealth.79

The diplomatic style of Kiderlen has been characterised as being ‘to stamp on his neighbour’s foot and display aggrieved surprise if he received a kick in return’,80 though he had the approval of the Chancellor in despatching Panther.81 What the German Foreign Minister wanted to extract from France was the territory known as the French Congo or French Equatorial Africa, an immense area about four times the size of France.82 In gaining this colony he was thinking two steps ahead, inasmuch as he foresaw the advantages the possession of the territory would give Germany should the Belgian Congo ever be broken up. He clearly stated his position in a letter to Bethmann following upon the outbreak of the crisis:

The French understand that they must grant us compensation in the colonial realm. They want to keep this to a minimum, and the government will be bolstered in this by its fear of both parliament and the public sentiment generated by the Colonial Party. The French will only agree to an acceptable offer if they are firmly convinced that we are otherwise resolved to take extreme action. If we do not demonstrate this, then we will not receive, in return for our withdrawal from Morocco, the kind of compensation that a statesman could justify to the German people. This, in any case, is my conviction. We must gain all of the French Congo – it is our last opportunity to get a worthwhile piece of land in Africa without a fight. Regions in the Congo that have rubber and ivory, as nice as they may be, are of no use to us. We must go right up to the Belgian Congo so that, if it is divided up, we will take part in the partitioning. If this entity continues to exist, we will have access through it to our territories in East Africa. Any other solution would be a defeat to us, which we must be firmly resolved to avert.83

Perhaps thinking ahead two steps led him to neglect to ensure that the first step was achievable. In any event the German actions, in particular the ‘Panther’s’ leap to Agadir’ (Panthersprung nach Agadir) as it became popularly known, produced a huge reaction. In Churchill’s words: ‘All the alarm bells throughout Europe began immediately to quiver. France found herself in the presence of an act which could not be explained, the purpose behind which could not be measured.’84 Nowhere did the alarm bells quiver more than in the Italian foreign ministry. The British Ambassador to Italy, Sir James Rennell Rodd, reproduced the Italian version of events in his memoirs:

On the 1st of July 1911, the German Ambassador in Rome went to the Italian Foreign Office to announce to San Giuliano that the cruiser Panther had been sent to Agadir. The alleged reason for this step, the protection of German firms in the south of Morocco, was naturally received with considerable scepticism. It was not till nearly two years afterwards on the recurrence of the same date that San Giuliano admitted to me that on Jagow’s leaving his room he called in Prince Scalea [Pietro Lanza di Scalea], the Under-Secretary of State, and, taking out his watch, which marked five minutes to midday, observed to him that from that moment the question of Tripoli had entered on an active phase. Thereafter the process of preparing public opinion for what was to take place at the end of September began.85

We can probably discount the detail of this incident, particularly the notion that the Italian government was ‘preparing’ public opinion, but there is little doubt that the episode furnished further reasons for the ANI and their ilk. As one set of apologists for Italy’s actions were to put it: ‘if the cheque [Italy] had upon Tripoli was not to be rendered valueless in her hand she must cash it at once.’86 It was believed, or at least the nationalists tried to believe, that if Italy failed to seize Tripoli then Germany would:

[…] the Panther incident showed Germany’s heavy-mailed fist in a very ugly light. This fact, coupled with that of Germany’s growing influence at the Porte, and the granting of favours to Germans in Cyrenaica, lent colour to the report that an arrangement had been concluded for the Panther’s successor at Agadir to go to Tobruk. Italy’s ‘political necessity’ was plain.87

Such retrospective arguments have been correctly characterised as no more than ‘crude propaganda puffery,’88 but there seems little doubt that similar sentiments expressed at the time inflamed that all-important ‘public opinion.’ Indeed, whilst American ‘yellow journalism’ on the part of the Hearst and Pullitzer-owned titles89 is erroneously supposed to have led directly to the Spanish-American War – ‘The yellow press is not to blame for the Spanish-American War. It did not force – it could not have forced – the United States into hostilities with Spain over Cuba in 1898’90 – there seems little doubt that the Italian yellow press was instrumental in causing war with the Ottoman Empire. As Francesco Malgeri stated it, the press campaign ‘helped to create […] a climate of excited expectation, to delude which would have been […] very perilous for the survival of the Giolitti government.’91

This pressure is reflected in a memorandum drawn up by San Giuliano and dated 28 July 1911. Sent to the Prime Minister and Monarch, the document outlined the problems of reconciling an invasion of Tripoli with the ostensible policy of maintaining the Ottoman Empire. He considered that ‘within a few months’ Italy might be ‘forced to carry out the military operation to Tripoli,’ though should seek to avoid it. The reason for this avoidance being the ‘probability (though not certainty) that the blow […] would give to the prestige of the Ottoman Empire, will induce the people of the Balkans to action.’ This would then, in all likelihood, cause Austro-Hungarian intervention, which could damage Italian interests there. His solution to these matters was that Italy, once decided on invasion, should act quickly and with such force as to have the matter decided before complications could arise: ‘It is necessary that all of Europe should find itself in the presence of a fait accompli almost before examining it, and that the situation which follows in international relations should be rapidly liquidated.’ He pointed out that Ottoman military problems, and Italian naval preponderance, would render it difficult for the province to be reinforced. The enterprise was therefore, in the military and naval context, feasible though future Ottoman naval improvements would make this less so in the future. The extent of the operation should go no further than the occupation of the port cities of Tripoli and Benghazi, and:

This done, we should give to the exercise of our sovereignty over Tripoli the form best suited to reducing to a minimum, at least for a few years, our expenses and the permanent employment of Italian military forces in those regions. It would probably be possible to use the dynasty of the Qaramanli, which has not yet been extinguished, or to come to a solution with Turkey like that adopted for Bosnia in 1878 or with China by Germany and the other European powers.92

It was, in the context within which it was constructed, a reasonable summary of the situation, together with a solution to potential problems. Though it was to be proved hopelessly optimistic in several areas, it was only factually wrong in its assessments of Ottoman naval potential. The Ottoman Navy in 1911 was a negligible force. In terms of battleships its most modern units were two ex-German Brandenburg class vessels. Commissioned in 1894 as SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and SMS Weißenburg they had been purchased in 1910 and renamed Hayreddin Barbarossa and Turgut Reis respectively. With a displacement of some 10,500 tonnes, and armed with a main battery of six 28 cm guns, these vessels were obsolete stopgaps. The CUP, aware of Ottoman naval incapacity, had sought to remedy it by ordering two new dreadnought battleships from British shipbuilders in June 1911, only one of which was to come to fruition. Vickers laid down this vessel, Reshadiye, a slight variation on the Royal Navy’s King George V class battleship design, on 1 August 1911. The ship was not to be completed until 1914.93

The Hayreddin Barbarossa was one of two Brandenburg Class battleships acquired by the Ottoman Empire from Germany in 1910. Originally SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm, and dating from 1893, the vessel was utterly obsolete when Italy declared war and the Ottoman Fleet wisely refused battle with the more modern and powerful enemy. That this was prudent was confirmed somewhat during the First Balkan War when, during the battles of Elli (3 December 1912) and Lemnos (5 January 1913), an Ottoman contingent centred on the two battleships was unable to prevail against a Greek detachment consisting of lighter ships. They were thus prevented from venturing into the Aegean. The heaviest Greek unit was the armoured-cruiser Georgios Averof that had been constructed in Italy and was a member of the Pisa Class, though with a slightly lighter main armament. (Author’s Collection).

The Italian Navy was also lacking dreadnoughts in 1911, though had laid four down; one in 1909, Dante Alighieri, and three more, Conte di Cavour, Giulio Cesare and Leonardo da Vinci, in 1910. Nevertheless, against anything other than a dreadnought-armed opponent it was still a powerful force, and against the Ottoman Navy an irresistible one. Its main units comprised the four Regina Elena (sometimes categorised as Vittorio Emanuele) class battleships; Regina Elena, Vittorio Emanuele, Napoli, and Roma. Commissioned between 1901 and 1903 these were fast vessels, though somewhat lightly armed with a main battery of only two 305 mm guns each in single turrets. There were also two ships of the slightly older, (though with main batteries of four 305 mm more heavily gunned), Regina Margherita class, Regina Margherita and Benedetto Brin. Completed in 1904 and 1905 respectively, the former was the Mediterranean fleet flagship, though unavailable in 1911 due to explosion damage sustained whilst in dock. Complementing these were two Ammiraglio di Saint Bon class ships, Ammiraglio di Saint Bon and Emanuele Filiberto, each having four 254 mm guns in their main battery and commissioned in 1901. There were a further three battleships of the Re Umberto class; Re Umberto, Sicilia and Sardegna. Completed 1893-1895, and each armed with obsolescent main batteries of four British 13.5 inch naval guns (also known as the ‘67-ton gun’), these ships would have been of little utility against even a moderately armed naval opponent.

If Ottoman naval strength in terms of capital ships was pathetic, its strength in cruisers was equally feeble, basically consisting of two protected cruisers (having a protective deck covering the machinery and other vitals). These were the British built Hamidiye (Hamidieh) launched in 1903 and the US constructed Medjidieh (Medjidiye) completed in 1904. Italy though could deploy a number of modern armoured cruisers (fitted with side armour in addition to a protective deck), such as the two vessels of the San Georgio class completed in 1910. San Giorgio and San Marco were powerful ships heavily armed with four 254 mm and eight 203 mm guns and capable of attaining some 23 knots. Also modern were the Pisa class ships; Pisa and Amalfi commissioned in 1909. These were also relatively heavily gunned; the main battery consisted of four 254 mm guns mounted in two twin turrets, whilst there were eight 190.5 mm in the four turrets of the secondary battery. The navy also deployed three older armoured cruisers of the Giuseppe Garibaldi class, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1902), Francesco Ferruccio (1899) andVarese (1902), as well as two Vettor Pisani class ships: Vettor Pisani (1895) and Carlo Alberto (1896). A single, eponymous, member of the Marco Polo class (1892) completed the list.94

Ottoman vessels of the lighter types were more modern. They possessed four German constructed destroyers of the S165 class laid down in 1910. Renamed Jadhigar-I-Millet, Numene-I-Hamije, Muavenet-i Milliye and Gairet-I-Watanije, these ships displaced some 620 tonnes and were able to make 33 knots. The Imperial German Navy had originally designated them as large torpedo boats, and accordingly their main armament consisted of three 45 cm torpedo tubes. Slightly older (1908), and rather smaller at 305 tonnes, were four French Durandal class vessels, designated as Basra class in Ottoman service: Basra, Tasoz, Samsun, and Yarhisar.These might have been roughly comparable with Italian units of the same type, such as the 910 tonne Soldati Artigliere class of 1906-10 or the 924 tonne 1911 Soldati Alpino class. However, to paraphrase Sir Andrew Cunningham’s alleged phrase, whilst it may take only a few years to build a ship, it takes a lot longer to build a navy. Put simply, in contradistinction to the Italian, the Ottoman Navy had no real organisation, doctrine or culture in 1911, and it would take time to rectify these deficiencies.

There was thus no way that the Ottoman Navy could catch up with the Italian in any reasonably foreseeable future. Command of the sea was then easily achievable by Italy, and despite the Ottoman territory not being an island it was this command that would dominate the issue; Ottoman military forces in Tripoli could not be easily reinforced or indeed supplied via that route.

If San Giuliano’s conversion to the principle of Italian military intervention seems established by his memorandum of 28 July, then his diplomatic moves sought to camouflage this. For example, on 26 July the Italian ambassador to London, Guglielmo Imperiali, had met with the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey. The ‘problems’ Italy was having with the regime in Tripoli were related, and, according to Grey’s account of the conversation sent to his representative in Rome two days later, he had told Imperiali:

[…] I desired to sympathize with Italy, in view of the very good relations between us. If it really was the case that Italians were receiving unfair and adverse economic treatment in Tripoli – a place where such treatment was especially disadvantageous to Italy – and should the hand of Italy be forced, I would, if need be, express to the Turks the opinion that, in face of the unfair treatment meted out to Italians, the Turkish Government could not expect anything else.95

It does not seem, however, that Grey expected military action to ensue as a result of the ‘unfair and adverse’ treatment described. Indeed, on 30 August 1911 he apprised the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Sir Gerard Lowther, of his discussion with Imperiali, and asked him to convey to the Ottoman Foreign Minister the message that ‘His Majesty’s Government understands the complaint of the Italian Government to be that they receive less favourable treatment in Tripoli than other nations.’96 Further, San Guiliano’s conversations on the subject with the ambassadors of Italy’s allies, Austria-Hungary and Germany, held on 29 July 1911, seem to have revolved around telling them that his government might be forced into ‘energetic action’ by the ‘atrocious calumnies’ being published in Tripoli regarding the Italian Army.97

It was certainly the case that San Giuliano and Giolotti were reluctant to inform any of the other Great Powers over the true nature of their deliberations concerning Tripoli. This was from fear that, as had happened vis-à-vis France and Germany concerning Morocco in the Tangier, or First Moroccan, Crisis of 1905-6, and indeed the more recent Second Moroccan, or Agadir, Crisis that was still in the process of being negotiated away (the Treaty of Fez was signed on 30 March 1912), pressure would be brought to organise a conference where Italy would have had her demands effectively arbitrated. As Giolitti put it in his memoirs (published some eleven years later):

[…] while European public opinion worried much of the dangers of the Moroccan crisis, our action would have attracted smaller attention […] waiting for the resolution of the Moroccan issue, meant the issue of Libia [Tripoli] would be itself introduced into the diplomatic field [and] Great Power consent would have been subject to negotiation and conditions that would have much complicated the matter.98

At roughly the same time as the British Foreign Secretary was telling his ambassador to the Ottoman Empire to pass on his understanding of the Tripoli situation, his Italian counterpart was sounding opinion from Italy’s ambassadors to the various Great Powers. Some discretion was required of these diplomats, as they were required to ascertain the attitudes of the states they were accredited to in the event of Italian action in Tripoli, without giving away the fact that such action was forthcoming. Despite, in particular, Germany’s friendly policy towards the Ottoman Empire (politica turcofila99), but probably because the intent behind the inquiries was kept well concealed, none of the replies were wholly negative; Giolitti specifically remarks on the ‘cordial attitude of England, France and Russia.’100 However during an interview between San Giuliano and Ludwig Ambrozy, the Austro-Hungarian Charge d’affaires at Rome, on 28 August the former had disingenuously argued that no immediate occupation was being considered provided legitimate Italian economic interests could be satisfied. Referring to the Italian press campaign, Ambrozy had replied that it was ‘a little too much to ask Turkey to promote the Italianisation of the economic life of Tripoli, when daily the press contests her right to the undisturbed possession of these provinces.’101 Indeed, such was the intensity of the campaign at this time that the British Ambassador was positive that public opinion in Italy, as expressed by the press, would cause the downfall of the government if it failed to do in Tripoli what it was perceived France was likely to do in Morocco.102 This press agitation intensified during September, when even those influential organs that had previously been neutral as regards Tripoli began pressing for action.103

The decision to definitely go to war has been traced by scholars as, according to Malgeri, occurring on the 14th, or, as per Bosworth, the 15th September 1911.104 This was the occasion when it was agreed between San Giuliano and Giolitti that, despite the potential disapproval of its Allies in the Triple-Alliance, whom they kept especially in the dark, military action would commence in November.105 However, on 2 September, San Giuliani, after being so informed by the deputy chief of the naval staff, had already warned Giolitti that the vagaries of late autumnal weather made a naval expedition at that time problematical.106 Having originally forgotten this perhaps he then remembered it the following day; in any event that was when he suggested that the date be brought forward to October.107

At more or less the same time, messages from Italy’s diplomats stationed in the capitals of the other Great Powers began to show various degrees of comprehension and alarm amongst those powers at what was afoot. Perhaps the most forthright was ventured by Germany, as Giolitti related it in his memoirs:

On the eve of the day on which hostilities were to begin, the Foreign Minister of Germany, Kiderlen-Wàchter, called our ambassador, Pansa, and tried persuading the Italian government not to declare war on Turkey, postulating the danger of perturbations in the Balkans and of the break-up of the Ottoman Empire.108

Childs unearthed the original of Pansa’s communication, dated 23 September, in the Italian archives, and it is rather more explicit than the version that made it into Giolotti’s memoirs:

[…] Italian military action and […] an Italo-Turkish war […] could have the gravest repercussions, provoking the separation of Crete, new risings in Albania, rebellion in the Yemen and perhaps an aggression by Bulgaria with the danger of the destruction of the Ottoman Empire […] in the presence of this eventuality there was room to consider if there were not some way to satisfy Italy’s aspirations in the future, who in the first place wanted to guarantee against the peril of Tripoli being occupied by another power.109

It may be recalled that the 1891 agreement with Germany, and the similar 1902 arrangement with Austria-Hungary, over Tripoli had stated that consultation would take place before any Italian move on the territory. These conditions, if they may be called that, would be disregarded if Italy suddenly invaded unilaterally. This did not seem to concern Giolitti who had already warned the military, under the Minister of War, General Paolo Spingardi, and the Chief of Staff, General Alberto Pollio, in August 1911 that an invasion was a probability in the near future. He had also told Pollio to calculate the forces necessary to accomplish it.110 Pollio, who had been appointed to his position in 1908, was a cerebral and scholarly soldier who had penned several works of military history including a work on the Battle of Custoza. He and Spingardi, who had been Minister for War since December 1909, were faced from the start with instituting and carrying through far-reaching army reforms, and these were far from complete when they were informed of the need to organize an expedition to Tripoli.111

Nevertheless, it cannot be argued plausibly that such a venture had to be extemporized at short notice. The problem, whilst still theoretical, had been the object of much study, with plans to carry it out dating back as far as 1884. These were updated following the defeat at Adowa in 1896, where deficient planning was deemed to have been a cause of the disaster, and two detailed studies were completed the following year. Further revisions were made in 1899, 1901, 1902, and again when the Tangier, or First Moroccan, Crisis of 1905-6 erupted. All of these plans were essentially variations on the same theme; the military expedition would, after landing, confine itself to occupying the various ports and significant coastal towns. A force of circa 35-40,000 men would be required for this operation, and there were no plans beyond taking the coastal areas or for advancing into the interior. That the possibility of having to carry out the mission was in Pollio’s mind before the crisis erupted is evidenced by his actions early in 1910. On 22 February he had distributed Circular 219 to army headquarters throughout Italy. This contained details relating to the mobilisation of an expeditionary force to Tripoli should the necessity arise, and there was a heavy correspondence on the matter throughout the latter part of 1910 and 1911 right up until September.112

One document, Study for the Occupation of Tripolitania, produced in August 1911, considered ‘all the complex problems’ and ‘studied the eventualities that might arise’ following the seizure of the initial coastal objectives. These included defending the Italian held territory from counter-attack from ‘the Turkish part of the country’ and measures to protect convoys. Further advances were to be limited to consolidating occupation of the coast by occupying secondary objectives. The military occupation of the hinterland was to proceed only by degree, and then only after the appropriate political and administrative action had been completed by the new regime installed in the capital, Tripoli.113 In other words, pacification, if it were required, of the interior would only take place, and then gradually, after the war with the Ottoman’s had been won.

Giolitti was to later claim that, following his August 1911 meeting with Pollio, he had advised the Chief of Staff that his initial estimate of the number of troops required to successfully carry out the operation was insufficient. According to Giolitti, writing in 1922, Pollio’s initial estimate was that 22,000 (ventiduemila) would suffice, which he advised should be increased to 40,000 (quarantamila). He also observed that ‘in reality’ the number of men required eventually exceeded 80,000 (ottantamila).114 Since Pollio died in 1914 he could not give his version. It is though probably safe to conclude that Giolitti’s memory was playing him false when he composed his memoirs. It seems unlikely that Pollio would explain a plan to him that was so at variance, in terms of numbers, with previous, and long standing, versions. Further, it might be thought a curious coincidence that the number of men settled on at Giolitti’s alleged insistence was much the same as the number the General Staff had been planning to utilize for over a decade.

It is also the case that Pollio knew what he was facing, at least in terms of topography and enemy numbers, via information collected by the General Staff’s intelligence office. The formal establishment of an intelligence section, Ufficio I, of the General Staff did not occur until 1900. Its growth was small; it employed only three agents outside Italy in 1906 and had no deciphering or code breaking section until 1915.115 This was undoubtedly due to the tight financial leash upon which it was kept. A new officer, Silvio Negri, a Colonel in the Bersaglieri, was appointed to head Ufficio I in July 1905, in which position he was to remain until September 1912.116 The majority of the intelligence work was directed towards the north-east of the state where lay the border with Austria-Hungary. However, from 1906, Colonel Negri also gathered information on Tripoli, utilising the information gathered by Italian geographers and similar, to produce detailed maps of the territory, particularly the coastal areas where any Italian landings would take place.117 What seems to have been neglected though is any appraisal of the likely attitude of the local population to a change of colonial masters, which, as will be seen, was to be a matter of no small consequence.

Unaware of the behind-the-scenes machinations of the government, the Italian press campaign had, by 24 September, reached a crescendo. The papers were full of the suffering being occasioned to Italians in Tripoli, claiming that they were in fear of being massacred by armed mobs egged on by militant imams preaching vitriolic hatred of infidels.118 This was all nonsense, of course, but San Giuliano seems to have used this supposed ‘explosion of fanaticism’ in Tripoli, fomented as he claimed by Turkish officials, to inform the ambassadors to the Great Powers that the Italian government might be obliged to take action.119 Others, both in government and otherwise had, of course, deduced that Italian action was imminent. For example, The New York Times of 25 September 1911 carried a report, sent by ‘special cable’ from London the previous day:

The quarrel between Italy and Turkey over Tripoli has developed with surprising suddenness. The Italian Government has called the reservists of 1908 back to the colours, and warships and troops are ready to sail for Tripoli. […] Italian merchant ships are leaving Turkish ports without waiting for complete cargoes […] The ostensible cause of the trouble between the two powers is the treatment of Italian subjects and Italian trade in Tripoli […] The Turkish Government on its part has for some time been dispatching arms and munitions of war to Tripoli […]120

Though the press has never been noted for its accuracy, the last point made in the piece had some veracity. Though sources differ, sometimes considerably, the Ottoman garrison in Tripoli and Cyrenaica, which consisted of the regular 42nd Division, had a nominal strength of around 12,000. However, this division had been ‘raided’ in January 1911 in order to provide manpower for suppressing a rebellion that had broken out in Yemen. Accordingly, there were only about half that many, and possibly only about a quarter, available in September 1911.121 There were also a number of territorial troops, reservists, and the like, amounting to several thousand. In order to assist this weak force a shipment of 20,000 modern rifles, probably ‘Turkish Model 1893’ Mausers, plus two million rounds of ammunition, and several light artillery pieces were dispatched aboard the steamer Derna on 21 September. The shipment arrived at Tripoli on 25 September and was no doubt swiftly unloaded.122

This was the only military action, if it may be called that, taken by the Ottoman government prior to the outbreak of war. Indeed, Ottoman passivity in the face of what was an obvious and building crisis is, in retrospect, astonishing. As one Turkish scholar has stated it: ‘the Sublime Porte officially kept repeating that, “Italy had no intentions on Tripoli” until war was actually declared by the latter.’123 Even in the diplomatic sphere the Ottoman’s appeared very slow to realize the threat from Italy. However on the same day as the Derna docked, the German ambassador to Istanbul, the former State Secretary for Foreign Affairs Adolf Marschall von Bieberstein, discussed the Tripoli situation with Ibrahim Hakkı Pasa, the Grand Vizier. Germany would be placed in an awkward position if conflict arose; its politica turcofila in terms of one state would have to be reconciled with its formal alliance with the other. This was a situation that Marschall, who had been ambassador at Istanbul since 1897 and who had overseen the recent growth of friendly relations with, and German presence in, the Ottoman Empire, sought to avoid. He was it seems pushing at an open door, in the sense that Hakki was prepared to concede almost anything – Italy could construct railways, roads, ports and the like – ‘consonant with the character of the country as a Turkish province.’124 Whilst Marschall passed this information on to his government, Hakki reiterated it to the Italian chargé d’affaires, Giacomo De Martino whom he saw next. This information was passed to San Giuliano on 26 September, the same day that Marschall met De Martino to impress upon him that Italy should avoid military action. His reasons being similar to those that his superior in Berlin was attempting to impress on the Italian ambassador there: the danger of perturbations in the Balkans and of the break-up of the Ottoman Empire. Also on 26 September, the Ottoman chargé d’affaires in Rome reinforced Hakki’s point about concessions to San Giuliano.125

Thus, as Childs points out, San Giuliano and Giolitti knew on that date that a peaceful resolution was possible, but rejected such a solution.126 Or, as Raymond Poincaré, the soon to be Prime Minister (1912) and then President of France (1913), unequivocally stated it: ‘To the belated Turkish overtures Italy replied with a blunt ultimatum, in which she announced a military occupation of Tripoli.’127 Indeed, it was on 26 September that San Giuliano ordered his staff at the Consulta (the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, from its location in the Palazzo della Consulta adjoining the Piazza del Quirinale) to finalise the ultimatum, which was undeniably bluntly phrased and full of disingenuous humbug (the full text, and that of the Ottoman reply, can be found in Appendix A). The essentials of it though were contained in the penultimate paragraph:

The Italian Government, therefore, finding itself forced to think of the guardianship of its dignity and its interests, has decided to proceed to the military occupation of Tripoli and Cyrenaica. This solution is the only one Italy can decide upon, and the Royal [Italian] Government expects that the Imperial [Ottoman] Government will in consequence give orders so that it may meet with no opposition from the present Ottoman representatives, and that the measures which will be the necessary consequence may be effected without difficulty. Subsequent agreements would be made between the two governments to settle the definitive situation arising therefrom. The Royal Ambassador in Constantinople has orders to ask for a peremptory reply on this matter from the Ottoman Government within twenty-four hours from the presentation of the present document, in default of which the Italian Government will be obliged to proceed to the immediate execution of the measures destined to ensure the occupation.128

This was telegraphed to De Martino on 27 September, and he duly delivered it to an apparently surprised Hakkı at 14:30 hrs on 28 September.129 The ‘dignified and concilitary’ Ottoman reply, which was in total contradistinction to the hectoring tone of the Italian text, was delivered within the twenty-four hour period. It sought to offer assurances, and argued that differences between the two governments were the results of easily adjusted misunderstandings:

Reduced to its essential terms the actual disagreement resides in the absence of guarantee likely to reassure the Italian Government regarding the economic expansion of interests in Tripoli and in Cyrenaica. By not resorting to an act so grave as a military occupation, the Royal Government will find the Sublime Porte quite agreeable to the removal of the disagreement.

Therefore, in an impartial spirit, the Imperial Government requests that the Royal Government be good enough to make known to it the nature of these guarantees, to which it will readily consent if they are not to affect its territorial integrity. To this end it will refrain, during the parleys from modifying in any manner whatever the present situation of Tripoli and of Cyrenaica in military matters; and it is to be hoped that, yielding to the sincere disposition of the Sublime Porte, the Royal Government will acquiesce in this proposition.131

No reply, unless it immediately conceded the unfettered right of Italy to occupy Tripoli, could have satisfied San Giuliano and Giolitti, or indeed Italian ‘public opinion.’ Indeed, it is doubtful if even that would have sufficed. They wanted a war, not, as Clausewitz had it, as a continuation of politics by other means, but as a matter of policy in order to satisfy ‘public opinion.’ Accordingly, on the day the reply was received, De Martino handed the following text to the Ottoman government:

[…] the period accorded by the Royal Government to the Porte with a view to the realisation of certain necessary measures has expired without a satisfactory reply […] The lack of this reply only confirms the bad will or want of power of which the Turkish Government and authorities have given such frequent proof […] The Royal Government is consequently obliged to attend itself to the safeguarding of its rights and interests as well as its honour and dignity by all means at its disposal. The events which will follow can only be regarded as the necessary consequence of the conduct followed for so long by the Turkish authorities. The relations of friendship and peace being therefore interrupted between the two countries, Italy considers herself from this moment in a state of war with Turkey.131

There is an Arabic saying to the effect that ‘he who takes a donkey up a minaret must take it down again.’ Giolitti and San Giuliano, with much additional pushing from Italian ‘public opinion,’ had then quite easily carried their donkey to the very top of the Tripol minaret; they were to discover that getting it down again was a somewhat more complex, and infinitely more arduous, task.