The Italian’s Land

‘We advised the Ottoman government to conduct a guerrilla war from the interior of the country. The Italians may control the coast, which will not be difficult for them with the assistance of the heavy guns of their fleet. Mounted Arab troops led by young Turkish officers will remain in constant contact with the Italians, giving them no rest by day or night. Small detachments of the enemy will be overwhelmed and crushed, whilst larger ones will be avoided. We shall try to lure the enemy from his coastal bases with night attacks, and destroy those that advance.’

Enver Pasa, diary entry, 4 October 19111

ABRUZZI’S command in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas was not the only independent Italian naval unit. The outbreak of hostilities in Tripoli overlapped with Ottoman troubles in the Yemen vilayet and the neighbouring mutasarrifiyya (sub-governorate) of Asir (now a province of Saudi Arabia). Ottoman sovereignty was particularly disputed by the Idrisi, under the leadership of Sayyid Muhammad Ibn Ali al-Idrisi, who had been in a state of more or less continual insurrection from 1904.2 Indeed, part of the reason for Ottoman forces in North Africa being weak related to Yemen and Asir; a goodly proportion of the Tripoli garrison had been redeployed there to restore order.3 A new Vali, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasa, had been appointed in 1910 and his policy, aided by Sharif Faysal (Feisal) of later Arab Revolt fame, was one of repression and military occupation. This policy had succeeded, to the extent that by the beginning of October 1911 the Ottoman forces had regained control of the port city of Jizan, Asir.4

When the Italo-Ottoman conflict broke out, Idrisi saw it as a case of ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend.’ The Italians thought along similar lines, and under this temporary and unofficial alliance their naval units in the Red Sea, based in Eritrea, actively aided the insurgents and attacked Ottoman coastal installations. Fear of this policy caused the hurried abandonment of Jizan, with a great loss of stores and equipment, whereupon the Idrisi quickly took repossession. From Italy’s point of view this meant it was neutralised, but there were still several major Yemeni ports in Ottoman hands, mainly al Hudaydah (Hodeidah, Hudayda), al Mukha (Mocha, Mocca Mokha) and Cheikh Said (Shaykh Said).

The Italian naval presence in the Red Sea was neither large nor powerful, the main units in October 1911 being the old Umbria class protected cruisers Elba (1893), Liguria (1893), and Puglia (1898), together with the similarly designated Etna class Etna (1885) and (later) the Piemonte class Piemonte (1888). Other vessels of note included the Partenope class torpedo-cruiser Aretusa, the Curatone class gunboat Volturno (1887) and Governolo class Governolo (1894). This still greatly outgunned anything the Ottoman navy would be likely to deploy, their available units in the theatre amounting to seven torpedo boats. In any event, and despite the age and weakness of his vessels, a blockade of the coast was maintained without undue difficulty under the dynamic leadership of Captain Giovanni Cerrina-Feroni.

One minor incident occurred on 2 October when Aretusa and Volturno engaged the torpedo gunboat Peik-I-Shevket (Peyk i evket) near al Hudaydah and chased it into the harbour there. The Italians then bombarded the quays and forts before withdrawing, having destroyed a small vessel belonging to the customs. As elsewhere, Italian naval preponderance prevented much in the way of Ottoman activity, though there was to be a fight of sorts on 7-8 January 1912 at Al Qunfidhah (Konfida, Kunfuda, Qunfudah, Cunfida).

More immediately though, the Italian C-in-C, Vice-Admiral Augusto Aubry, a former parliamentary deputy and State Secretary of the Navy (December 1903-December 1905), had organized his available units into two Squadrons and a separate Division and made ready to seize objectives on the coast of Tripoli. Aged 62 and a Neapolitan of humble background, Aubry had fought at Lissa and had extensive naval experience.5 He commanded the 1st Squadron, and its 1st Division, made up of the four battleships of the Vittorio Emanuele class, in person, flying his flag aboard Vittorio Emanuel III.6 The 2nd Division was under Rear-Admiral Ernesto Presbitero and consisted of the armoured cruisers Pisa (flag), Amalfi, San Giorgio and San Marco, together with supporting vessels.7 The 3rd and 4th Divisions were organized as the 2nd Squadron under Vice-Admiral Luigi Faravelli. Faravelli commanded the 3rd Division from Benedetto Brin, the other major units being Regina Margherita (which was repairing and did not join until 5 October), Ammiraglio di Saint Bon and Emanuele Filiberto. The 4th Division under Rear-Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel was constructed around three armoured cruisers: Giuseppe Garibaldi (flag), Francesco Ferruccio andVarese. Marco Polo, following the cessation of activity in the Adriatic, was also appointed to the 4th Division. Established outside the two Squadrons was a fifth Division under Rear-Admiral Raffaele Borea Ricci. Entitled the ‘Training Division’ the heavy units consisted of the older and obsolete battleships Re Umberto, Sicilia (flag) and Sardegna, plus the armoured cruiser Carlo Alberto.

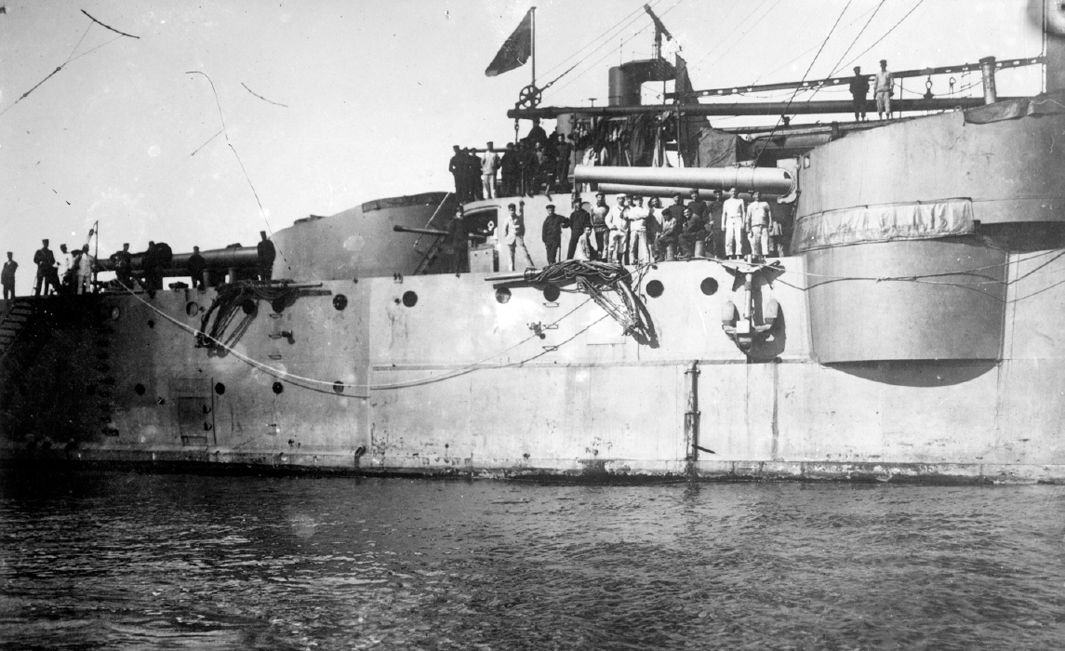

The Italian armoured cruiser Pisa off Derna. The town was approached by the armoured cruisers of the 2nd Division under Rear-Admiral Ernesto Presbitero on 15 October 1911. The division was escorting transports carrying troops from the 22nd Infantry Regiment who were to take possession of the town. However the Ottoman garrison rebuffed attempts at negotiations and Pisa opened fire against two observably military installations; a barracks and a fort. There was no reply and after 45 minutes the bombardment ceased and an attempt was made to send in a boat flying a flag of truce. This however this was met with rifle fire from Ottoman forces entrenched around the town. The four armoured cruisers then opened fire on Derna itself, and virtually destroyed it within 30 minutes. Attempts at landing were however thwarted by the sea state combined with the fire of Ottoman troops stationed on the beach. Despite heavy shelling from the fleet, these troops could not be dislodged and only after a stalemate lasting until 18 October did the Ottoman forces abandon their positions, allowing the landing of some 1,500 men. (Author’s Collection).

Aubry had concentrated the greater portion of his fleet at Augusta, Sicily, prior to the declaration of war on 29 September. Even before that declaration, on 28 September, the greater part of the 2nd Squadron and the Training Division, under the overall command of Faravelli, had left. This fleet then cruised between Malta and Tripoli, ready, as one enthusiast for Italy’s mission put it, ‘to bear down on the latter place if the Turkish and Mussulman fanatics of the town should attack our fellow-countrymen or the many other Europeans in residence there.’8 They arrived off the coast on the evening of 1 October and proceeded to dredge up the Malta-Tripoli cable, which was then cut. Tripoli was thus prevented from communicating with Istanbul in particular and the outside world in general.

Some twenty-four hours later the Giuseppe Garibaldi, with Rear-Admiral Revel aboard, entered the harbour. Under a white flag of truce Revel communicated a demand for the capitulation of the town; if no surrender was forthcoming by noon the next day (3 October) it would be subject to naval bombardment. He also offered safe passage to the various foreign consuls, and indeed any Europeans in general, who wished to leave in safety before any action began. Sources differ as to the details of what happened in response to this ultimatum. Some claim that at the instigation of the German Consul Dr Alfred Tilger, who was greatly concerned about the economic harm an Italo-Ottoman conflict would cause, a meeting was convened between the other consuls and the Ottoman authorities.9 During the course of this meeting the Ottoman authorities, the effective military commander being Nesat Bey under the nominal command of Munir Pasa, passed on the information that it had already been decided to evacuate the town. The upshot was that other than a small force left to man the coastal defences, the garrison had already withdrawn; a manoeuvre proposed by Enver on 4 October.

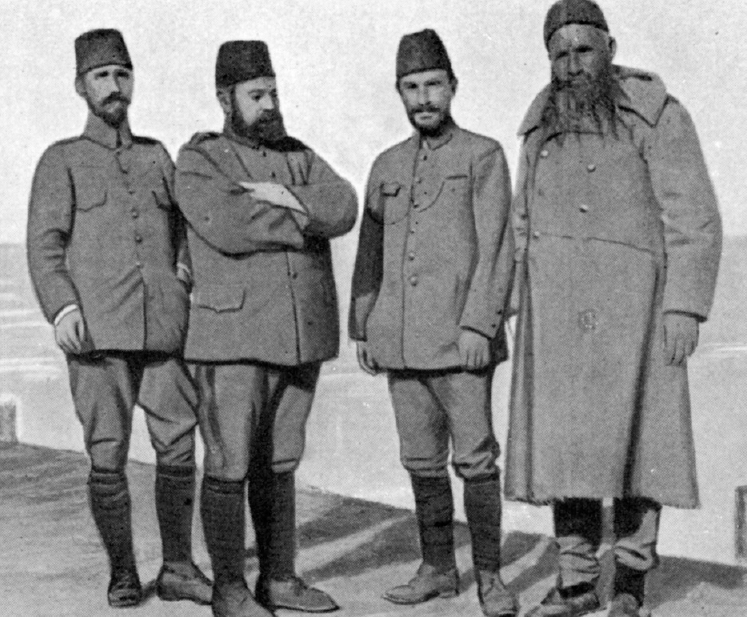

Ottoman Commanders in Tripolitania. From left-right: Fethi Bey, Nesat Bey, Taher Bey and Ahmed Choukri Baba. The latter was captain of the artillery.

One of the leading lights in the CUP, Enver had been the Ottoman military attaché in Berlin since 1909. He resigned his post upon hearing of the Italian invasion and travelled back to the Ottoman capitol via Thessalonica (Salonica), where the annual conference of the CUP was being held. According to his diary published in 1918 he was met at Thessalonica railway station on 4 October 1911 by friends who took him directly to the CUP Central Committee.10

According to Enver’s account the debate lasted more than five hours, but eventually it was agreed that the government would be advised that Ottoman forces withdraw from the coast into the interior of the country and adopt a guerrilla strategy. The coastal area would be left to Italy, who, with the heavy artillery of their naval vessels would not find it difficult to control, whilst the resistance gathered their forces in the interior. These, consisting of ‘Mounted Arab troops, commanded by young Turkish officers, will remain in constant touch with the Italians and constantly harass them day and night.’ Small detachments of the enemy would be ‘overwhelmed and crushed’ whilst larger formations would be avoided. Attempts would be made to lure the enemy out of the coastal enclaves by subjecting them to night attack, and any advance that thus ensued would be destroyed.11 Hakki had resigned upon the commencement of hostilities, but Enver’s advice, perforce, was taken by the new cabinet under Said Pasa and announced in the press.12 Enver was one of those sent to command this effort.13

That Enver was entirely correct in his calculation concerning conventional warfare may be adjudged by the state of the defences of Tripoli, which consisted of obsolete coast defence fortifications. To the west, and some way inland, there were a group of three earthen works, designated simply as A, B and C. To the north of these there was a coastal earthwork named Fort Sultanje or Fort Gargaresch. The harbour defences consisted of three masonry works; the Lighthouse Fort and Fort Rosso (Red Fort) built on the harbour wall, and the Spanish Fort constructed on the mole. A larger earthwork, Fort Hamidije or Scharaschat, was constructed to the east of Tripoli at a distance of about 5.5 kilometres.

Despite the decision to not defend Tripoli, there was no formal surrender. Accordingly, Faravelli moved in on 3 October, arranged his fleet into divisions for the attack. The 3rd Division bombarding the harbour forts, whilst the 4th Division took on Fort Hamidieh to the east and the Training Division Fort Sultanje. There were many foreign correspondents present to describe the event; Francis McCullagh of the Westminster Gazette for example:

The central forts were attacked first and the first shot was fired at the red fort on the mole at exactly 3.35 p.m. It was fired by the Brin and it hit the exterior surface of the fort, but injured nobody. The second shot was also fired by the Brin. When a third shot was fired the lighthouse battery answered for the first time, but the shot did not reach half-way to the ship for which it was intended.

This bombardment – for it cannot be called a duel – was carried on at a distance of only three or four miles and was the tamest affair imaginable. The Italians were so close that they could hardly have missed if they had tried. Consequently they did great damage, knocking down the lighthouse, overturning the guns, and converting the fort into a heap of ruins.14

The harbour works ceased firing at 17:00 hrs whilst the outer earthworks, being less susceptible to naval shell, continued firing until sunset at about 18:00 hrs. No fire had been directed into the city; nevertheless several stray rounds had missed their target and caused damage and fires. Much of the population of Tripoli that remained (most of the Europeans had, taking advantage of the offer to evacuate, already left aboard the SS Hercules) now found itself in an anarchic situation as the Ottoman forces withdrew. Though many people had fled the urban area out of fear of naval gunfire, those that remained indulged themselves during the absence of the forces of order. One community that found itself under attack from rioters and the like were the Jews. This population was to a degree segregated inasmuch as it was congregated in its own quarters, areas that were well defined and relatively easy to defend. Fortuitously, the CUP Ottoman government had in 1911 begun conscripting non-Muslims in the Tripoli vilayet into the army. It followed that some 59 Jews had received military training and, more importantly, had been mobilised and thus issued with arms.15 At least some of these remained in the city with their arms, and managed to defend their communities, fighting off the mob that tried to invade the Jewish areas during the interregnum between Ottoman and Italian rule.16

The Italian fleet returned at 06:00 hrs the next morning (4 October) and, after being fired on by Fort Hamidije, resumed bombarding the earthwork forts. Within an hour these were silenced, and after having satisfied himself that they would offer no further resistance Faravelli ordered a landing. Aboard the fleet were some 1,700 marines or naval infantry (fanteria di marina), and under the guns of the fleet the majority of these made landfall at Gargaresh to the west of the city.17

Since these marines were the only troops available to the Italians until such time as army mobilisation was completed, it was fortunate for the Italian cause that the Ottoman military had completed their withdrawal two days earlier. Indeed, Nesat Bey, though still under the nominal command of Munir Pasa, had commandeered all the transport camels within Tripoli and its environs, collected provisions for 5,000 men for three months, and mobilised as many militia troops as he could locate and moved them all away from the coast to the inland oases. The regular forces he had also removed but these were initially kept concentrated around Bumeliana (Bu Meliana, Boumelliana). This was the site of several wells from which Tripoli, via a station equipped with a reciprocating steam pump, drew most of its water.18 Situated some three kilometres south of the city on the edge of the desert it was, by virtue of the water supply, a strategically important point. It seems likely that if Nesat had known of the weakness of the Italian landing force he would have modified his strategy and attempted some form of resistance or counterattack. Indeed, the landing was only possible because of the Ottoman withdrawal under the threat from the guns of the fleet, which would have been of little utility in terms of supporting any fighting in the urban environment of Tripoli. The marines, under the command of Captain Umberto Cagni (the President of the International Polar Commission, who had been with Abruzzi during several of his explorations), swiftly moved beyond the urban area and formed a thin defensive perimeter on the outskirts of the oasis of Tripoli, the hinterland immediately beyond the city. This included Bumeliana, and since this was well within range of the fleet the majority of the Ottoman force withdrew a distance of around 80 kilometres – or about two days travel – to Gharian, a mountain stronghold some 580 metres above sea level. Nevertheless, the situation was militarily precarious for the Italian cause until such time as army units arrived in sufficient numbers to form a properly manned perimeter and to keep order within Tripoli if necessary.

If the military gaps could not be immediately filled, the same did not apply, or at least not to the same degree, in the civil sphere; Rear-Admiral Borea Ricci was appointed provisional governor. His deputy was Hassuna Qaramanli (Karamanli) who had occupied the position of mayor of Tripoli under the Ottomans. It may be recalled that San Giuliano had, in his memorandum of 28 July 1911, explored the possibility of using ‘the dynasty of the Qaramanli’ as a fig-leaf for Italian rule. Hassuna was indeed a member of that dynasty, being a descendant of Yusuf Pasa Qaramanli who had been deposed as ruler of Tripoli in 1835. He was in the pay of the Italian government to the tune of 4000 lira per month.19

That there was little or no disorder, and that the small force of marines was not overmuch troubled by attacks from the desert (there were several skirmishes) suggests two things. Firstly, that there was at that time little resistance to Italian occupation in the small area occupied, and, secondly, that the Ottoman forces were neither sure of the numbers they would face, nor organised enough, to mount any kind of well planned attack.

Whilst the 2nd Squadron and the Training Division supported the landing at Tripoli City and continued to help defend its occupiers Aubry and the 1st Squadron had sailed eastward, joining some units of his 2nd Division en route. His target was the Ottoman ‘fleet’; almost the entire operational Ottoman navy, the battleships Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis, together with the cruisers Hamidiye and Medjidieh and ten escorts, were exercising in the eastern Mediterranean during late September. This division-sized command had sailed from Beirut on 28 September and was headed north-west towards the islands of the Dodecanese (Southern Sporades). Not being equipped with wireless telegraphy equipment the vessels remained unaware of the Italian declaration of war, however whilst off Kos (Istankoy) they were hailed by an Ottoman vessel and informed of the situation. They immediately broke off their exercises and headed northwards at maximum speed, avoiding the central Aegean and keeping close in to the Anatolian coast. As the fleet transited the Gulf of Edremit between Lesbos (Midilli) and the mainland on 30 September it caused alarm at the island’s capital Mityleni, being mistaken for an Italian force. However, despite some erroneous reports of fighting a battle en route, the safety of the well-fortified Dardanelles was reached on 1 October and the Ottoman sea-going navy was safe, if rendered impotent. It was perhaps just as well for Anglo-Italian relations that Aubry, despite searching into the northern Aegean, was unable to find his target. It cannot have been unbeknown to him that it contained several British officers on secondment. Headed by Vice-Admiral Hugh Pigot Williams (a Rear Admiral in the Ottoman navy), these constituted the personnel of the 1910-1912 British Naval Mission to the Ottoman Empire. Williams had decided that he and his subordinates would remain onboard after receiving the news of war at Kos, but they went ashore for the duration of hostilities once safety was reached.20 On 4 October, and under exclusively Ottoman command, the fleet ventured out of the Dardanelles and stayed out for 24 hours whilst cruising in the vicinity of the entrance. Following this brief and ineffectual sortie the vessels remained anchored off Istanbul until 16 October.

His attempt to bring about a naval victory – which would probably have obviated the need to still refer to the ‘shame of Lissa’ as a reason for going to war in 191521 – having failed, Aubry then sailed for Cyrenaica. On 3 October his squadron anchored off Tobruk (Marsa-Tobruk, Tubruq) whilst the destroyer Agordat reconnoitred the harbour. Finding the defences minimal, the rest of the squadron entered the anchorage the following morning. The flagship fired a salvo at the ‘Turkish Fort’, which promptly signalled surrender by hauling down its flag. A landing party of some 500 marines and seamen then went ashore and, virtually unopposed, entered the fortification and raised the Italian flag. It had been a ridiculously easy victory and had gained for Italy the best natural harbour on the Cyrenaican coast, described by the British ethnologist Augustus H Keane in 1895 as ‘a spacious natural haven 34 feet [10.3 metres] deep and two miles [3.3 kilometres] long, sheltered from all except the east winds.’22 The marines were easily able to hold Tobruk, (the Ottoman garrison there had been reckoned to number perhaps 70 men), until elements of the first detachments of the Army Expeditionary Force, a battalion of the 40th Infantry Regiment supported by coastal artillery personnel and engineers, landed there on 10 October.

Meanwhile, the Ottoman regular forces had undertaken a probing attack at Bumeliana on 8 October and dispatches from Tripoli on 10 October carried accounts of two further attacks at the same location during the night. According to a report which appeared in several papers internationally, including the English Daily Express:

The Bumeliana fortification was attacked at 2 this morning with the object of cutting the aqueduct furnishing Tripoli with drinking water. The earthworks were held by 250 Italian marines under the command of Major Cagni. After twenty minutes heavy firing the Ottoman troops were repulsed. […] It had been expected that the Turks would attack the city, and the guards had been doubled at the wells […]

[A second attack] took place at about 3 o’clock, when sixty two men who had left their horses with the rear guard advanced within forty yards of the Bumeliana earthworks. They were obliged to leave a number of wounded on the field. […] Cagni had ordered his force to allow the Turks to advance to within 200 yards. There was absolute silence. When the Ottoman soldiers had deployed their entire line of skirmishers they dashed forward, but were stopped by heavy fire, direct and admirably regulated, which gave an impression of forces much superior to those which were really engaged.

The Turks were flung back into the sands. For five or six minutes small blue flames from their Mausers were seen, but immediately afterward they fled in disorder behind the dunes. The guns of the Carlo Alberto and Sicilia, which could now be used without danger to the Italians, began to thunder, following up with their missiles the flight of the retreating Turks.23

The Italians had reconnected the Malta-Tripoli cable, the sole means of communication to the outside world, shortly after taking occupation of Tripoli. They did though enforce a rigorous censorship, so that nothing but information that was approved by them could be despatched. Accordingly, all contemporaneous reports despatched from Tripoli have to be treated with the greatest caution; the very fact that they were sent at all means their contents were officially approved. So whilst some of the details of the skirmish described must be treated with prudence, that there was a fight of some kind is without doubt accurate. Nesat Bey was undoubtedly probing the Italian defences.

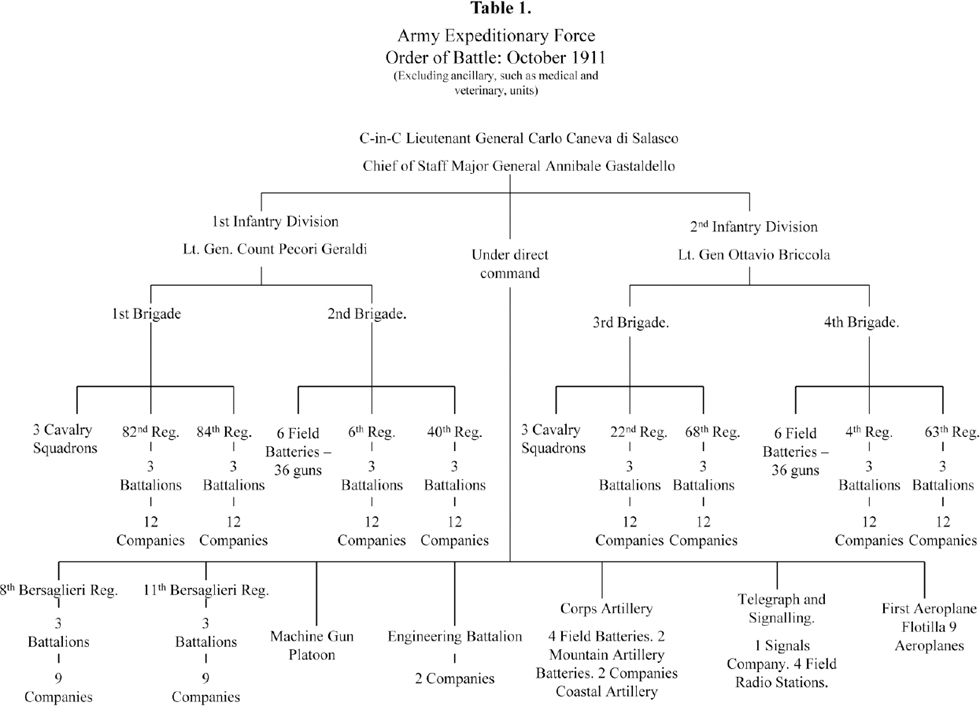

Indeed, the marines had held their Tripoli bridgehead for nearly a week unassisted and it could only be expected that Ottoman attacks would increase; reinforcements were urgently required. However, General Pollio had refused to be rushed. In a ‘Memorandum on the Occupation of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica’ dated 19 September 1911, he stated that ‘it is absolutely necessary, not only for the good name of the army but also for the dignity of the Nation, that this expedition to Tripolitania be organised in a perfect manner.’24 Organising such a venture in a perfect manner took time, particularly as he had to maintain sufficient forces to defend Italy’s northern and north-western frontiers with Austria-Hungary and France. He therefore ordered Army mobilisation, calling up the reserves on 27 September, whilst simultaneously drawing units from around the country to form an Expeditionary Force. This consisted of an army corps of 44,408 officers and men under Lieutenant-General Carlo Caneva di Salasco [Table 1 below]. Although the first units had been sent to Tobruk, in response to the potential situation at Tripoli, two regiments were despatched ahead of the main body aboard the fast ocean-going liners, Verona and Europa. Having sailed from Naples the 11th Bersaglieri under the direct command of Caneva, and (less one battalion) the 40th Infantry (forming part of Lieutenant-General Conte Pecori Geraldi’s 1st Infantry Division) disembarked at Tripoli on 11 October. These two regiments were required to reinforce the line for only one day, as, on the morning of 12 October, a fleet of some 18 transports plus escorts anchored off Tripoli with the rest of the Army Expeditionary Force. With the arrival of Caneva’s main body, the Italians were now secure in Tripoli and Tobruk.

The Armoured Cruiser Pisa. An excellent view from the starboard quarter of the stern armament on this armoured cruiser. The stern turret contained twin 254 mm (10 inch) guns whilst the wing turret was armed with a pair of 190.5 mm (7.5 inch) weapons. The two 75mm (3 inch) guns, the lower being casemate mounted, are also visible. The Pisa and her sister Amalfi were powerful examples of their type, though saw no ship-to-ship combat due to the Ottoman Navy’s (sensible) refusal to give battle. (George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress)

Pollio’s instructions from San Giuliano via Spingardi stipulated that the primary aims of the occupation force were twofold; the coastal region was to be occupied and the Ottoman forces were to be neutralised. There was to be no advance into the hinterland and, as the Italians were expecting to be welcomed as liberators, the non-Ottoman population was to be respected.25 Indeed, the army plan for the operation, as tweaked in August 1911, had called for nothing more than had now been accomplished other than ‘a few displays of force at coastal points duly selected as secondary objectives.’ Occupation of the rest of the vilayet ‘by degrees’ was perceived to be achievable by non-military means via ‘appropriate political and administrative action on the part of the new government installed at Tripoli.’26 This ‘new government’ was installed on 13 October when Caneva was named as Governor in succession to Borea Ricci. On the same day the marines were relieved of their military duties and rejoined the fleet.

The navy then began operations against the secondary objectives. Derna (Darnah) was approached by the armoured cruisers of the 2nd Division under Rear-Admiral Presbitero, escorting transports carrying troops from the 22nd Infantry Regiment, on 15 October. The town, some 200 kilometres west of Tobruk, is located at the eastern end of the inland Jebel Akhdar mountain range, which rises to some 500 metres and is one of the few regions that are forested. The area receives an annual rainfall of some 400-600 millimetres, meaning it was one of the few fertile portions of the territory the Italians were attempting to conquer. After the Ottoman garrison rebuffed attempts at negotiations, Pisa, Presbitero’s flagship, opened fire against two observably military installations; a barracks and a fort. Probably intended as an object lesson in the futility of resistance, fire continued for some 45 minutes but was not answered. Having ceased fire, Presbitero attempted to send in a boat flying a flag of truce, but this was met with rifle fire from Ottoman forces entrenched around the town. The four armoured cruisers then opened fire on Derna itself, and virtually destroyed it within 30 minutes. Attempts at landing via boat were however thwarted by the heavy sea combined with the fire of Ottoman troops stationed on the beach. Despite heavy shelling from the fleet, these troops could not be dislodged and thus undertaking an opposed amphibious landing was hazardous in the extreme. It was perhaps fortunate for the Italian Navy that after a stalemate lasting until 18 October the Ottoman forces abandoned their positions, allowing the landing of some 1,500 men.27

Whilst the operations against Derna proceeded, the armoured cruisers of the 4th Division, under Rear-Admiral Thaon di Revel, were despatched to carry out a similar mission against Homs (Al Khums, Khoms, Lebda), about 130 kilometres east of Tripoli. Aboard the transports were the 8th Bersaglieri Regiment and a field artillery battery, but a landing was found impossible to carry out on 16 October due, as at Derna, to the heavy sea and entrenched opposition. The defenders were estimated to number some 500 regulars with around 1,000 irregulars. The 4th Division conducted a long bombardment of the Ottoman positions, but it was not until 21 October that, the defenders having withdrawn, a difficult landing, during which two boatloads of soldiers were capsized, was completed.

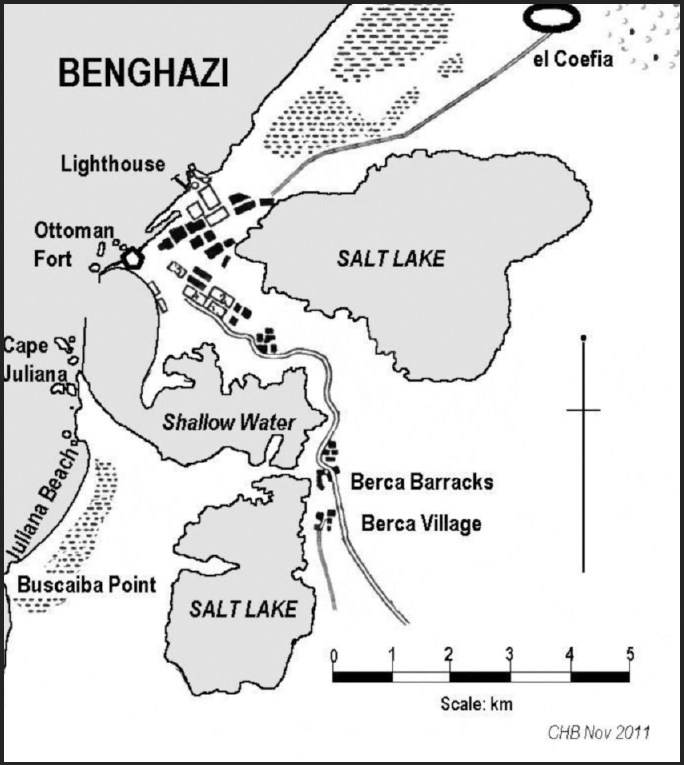

If Derna and Homs were taken and occupied relatively easily then the overlapping operation at Benghazi contrasted somewhat. There the Italian force had to carry out that most hazardous of manoeuvres; an opposed amphibious landing. The operation was undertaken by marines supported by elements of the 2nd Division of the Army Expeditionary Force. Though Briccola, as divisional chief, was in ultimate command, the force that was designated to undertake the operation was the 4th Brigade under Major-General Giovanni Ameglio, who had with him the 4th Regiment and two battalions from the 63rd Regiment. They were convoyed from Tripoli in eight transports under escort from Aubry’s 1st Division, arriving on the morning of 18 October. Although Benghazi was the second largest town in the vilayet, its population was estimated to be only around 5,000, it being a small trading post for the trans-Sahara caravan trade and an outpost for the Ottoman military.28 The permanent defences were minimal, consisting of a 16th century Ottoman fort, but there were a number of troops there, estimated at between 400-1,000 regulars and 2,500-3,000 irregulars equipped with about twelve field artillery pieces.

A Bersaglieri officer, Tullio Irace, was despatched with one companion under a flag of truce to demand the surrender of the place.

Towards noon the Admiral sent me shorewards with one other officer, to deliver to the Mutessarif, or Governor, his ‘ultimatum’ to surrender. Stopping our steam launch just off the Custom-house, we send to request the foreign Consuls to be good enough to meet us in conference […] We present to the Consuls the Admiral’s ‘ultimatum’ already made known to the Mutessarif. Time for decision is granted till 8 o’clock on the following morning: if by that hour the city has not hoisted the white flag or otherwise given proof of its decision to surrender, we should be compelled to have recourse to a forcible landing of troops.29

No sign of the surrender having been given, the next morning, with the weather being decidedly unpleasant, the Italians began operations. These opened with naval gunfire being directed on four areas: Juliana (Giuliana) beach (‘so called because the daughter of a foreign consul, of that name, had been buried there after an epidemic’30) where it was intended to land the troops, the Berca (Berka) barracks and fortress and nearby Governor’s residence, and a magazine to the north of the town.

The marines, numbering about 800, landed unopposed at about 08:50 hrs and moved to occupy positions in the dunes behind the beach and, using two 75 mm mountain artillery pieces, established a battery on high ground at Cape Juliana. It seems likely that the descent on Juliana Beach surprised the defenders. Had they foreseen it they could have occupied Cape Juliana and enfiladed the landing ground, even though any such forward defence would have been rendered problematical by naval gunfire. Indeed, a large proportion of the Ottoman force had been stationed to the north of Benghazi, and those south of the town were mainly deployed away from the shore. The latter group’s main position was on the narrow ground between the shallow water and a marsh to the south of it, with a thin line extended from the marsh to the south-west almost to Buscaiba Point. Perhaps realising the initial error of failing to occupy Cape Juliana an attempt was made to capture the Italian battery there and take the high ground. This manoeuvre was though thwarted by naval gunfire.

The marines managed to secure the beach to the extent that engineers were able to construct piers onto which troops could disembark from the ships’ boats, which, as well as a number of pontoon-floats and lighters, were used to ferry them from the transports. At 10:00 hrs Ameglio led the first of the military contingent ashore and took command of the beachhead. He ordered the marines to advance further inland in order to prevent any interference with the subsequent waves of troops. As they moved between the shallow water and the marsh they came up against the Ottoman position and found themselves unable to advance. However, they were quickly reinforced as more troops landed and were supported by the mountain battery on Cape Juliana. The divisional commander landed at 12:20 hrs and according to his retrospective report of the situation:

A strong detachment of the 4th Regiment and marines were entrenched, facing south and east, at the south end of the beach on the high ground near Point Buscaiba. Between the salt lake and the beach a mountain battery was in action, with the main body of the 4th Regiment forming up close by. Between this battery and the higher ground on Point Giuliana were the main body of the marines, detachments of the 4th and 63rd Regiments and the second mountain battery. On the high ground at Point Giuliana were two companies of the 63rd Regiment.31

By this time two battalions of 4th Regiment and one battalion of the 63rd Regiment were ashore, but the weather was becoming rougher causing problems in the landing of troops and equipment. It had been found impossible to disembark the mules that carried the mountain artillery – so the guns could not easily be moved – and ammunition in particular was running short. Briccola therefore decided to regroup and await reinforcement and supplies whilst considering the next phase of the operation. The objective was Berca, and the attack was to be made by advancing on and thus holding the enemy between the shallow water and the marsh whilst a second formation circled around the marsh and approached from the south.

The attack resumed at 15:30 hrs and was successful, with the result that by about 18:30 the Italians had dislodged the defenders. They advanced north and then northwest around the salt-lake, and past Berca, where the Italian flag was hoisted just as the sun set, to Sidi Ussein and the outskirts of Benghazi. It was now dark, but the defenders in Benghazi continued to fire at the Italians. Briccola therefore signalled to the fleet to bombard the town. The shelling started at 19:00 hrs and lasted some twenty minutes, after which the white flag was raised. However, amongst the buildings destroyed was the British Consulate, though the consul, Francis Jones, was unhurt. However, eight Maltese British subjects were amongst the twelve Europeans killed – nobody bothered to count how many non-Europeans perished – and according to Irace the British Consul was furious; ‘The Italians have fired on the British flag. This act will cost Italy dear!’32 It didn’t! In fact the only ‘cost’ was to Sir Edward Grey, who had to endure some rather irate questioning in the House of Commons.33

Benghazi. Utilizing their command of the sea the Italians made an amphibious descent at Juliana Beach, Benghazi, on the morning of 19 October 1911. Though the landings were virtually unopposed, strong resistance was encountered on the neck of land between the shallow water and the marshy salt lake. The enemy was fixed there whilst a second formation circled around the marsh and approached from the south. By about 18:30 hrs the Italians had dislodged the defenders and they advanced north and then north-west to Berca, where the Italian flag was hoisted. It was now dark but the defenders in Benghazi continued to fire at the invaders. The Italian fleet then bombarded the town for some twenty minutes, after which the white flag was raised. Amongst the buildings destroyed by the bombardment was the British Consulate. (© Charles Blackwood).

The Italian forces took possession of Benghazi on the morning of 20 October. They were unopposed within the urban area as, unable to respond to naval gunfire, the Ottoman forces had retreated to the hills inland of the town. Indeed, it had been the fire support from offshore that had made the enterprise possible. As a later exponent of the art, Sir Roger Keyes, was to put it: ‘To launch and maintain an amphibious operation, it is necessary to possess Sea Supremacy in the theatre of the enterprise […].’34 The possession of such superiority does not of itself guarantee success however, and there can be no doubt that the Italian landing forces had performed a hazardous operation with skill. Some 6,000 troops were eventually landed, with losses amounting to 36 killed and 88 wounded, the most senior amongst the former being guardiamarina (midshipman) Mario Bianco. The dead in general were commemorated by a Monumento ai caduti della Cirenaica erected on Cape Juliana. Designed by Marcello Piacentini it bore the words ‘At dawn on 19 October 1911, the ships of Italy gave Cirenaica Latin civilization.’ (The RAF bombed it in 1941, presumably in error).35 The death of Bianco in particular inspired the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio to write La canzone di Mario Bianco, one of his Canzoni delle gesta d’Oltremare (‘Songs of Overseas Deeds’ or ‘Songs from the Overseas Action’) in 1912. This work was initially suppressed and then censored by the Giuliotto government, mainly because of one song entitled La canzone dei Dardanelli, which attacked other European nations, particularly Italy’s allies Austria-Hungary and Germany, for their indifference towards Ottoman barbarity and general dislike of Italy.36

The Italian Monument to the Fallen at Benghazi (Monumento ai caduti della Cirenaica). Those who perished during the operations to captures Benghazi on 19-20 October 1911 were commemorated by an obelisk-like structure erected on Cape Juliana. Designed by Marcello Piacentini it bore the words ‘At dawn on 19 October 1911, the ships of Italy gave Cirenaica Latin civilization.’ It was bombed by the RAF during the Second World War and destroyed. (Author’s Collection).

By 21 October 1911, Italian arms had gained all that the politicians had asked of them. However, the plan for invading Tripoli left several interrelated questions unanswered. One of the most important from the military point of view being what was to be done to the Ottoman forces that had retreated from the beachheads? Caneva had pointed out to the Minister for War on 18 October the difficulties he foresaw in this regard. He stated that operations against the ‘main nucleus of regular Turkish troops’ were problematical because such a body did not exist. The Ottoman forces had become ‘dislocated,’ and now formed only ‘meagre detachments,’ which were at least six hours march from Tripoli. Dealing with them was a political rather than a military matter, achievable via a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire rather than by force.37 Indeed, wearing his political hat as Governor, Caneva had, on 12 October, issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of Tripoli, and indeed to the wider population if they got to see it, to the effect that they had been liberated from Ottoman rule. They were assured that their own chiefs, under the patronage of Victor Emmanuel III, would govern them. All their customs and religious laws would be respected, whilst unjust Ottoman taxes would be abolished. The address concluded by reiterating that Italy desired that Tripoli shall remain a land of Islam under the protection of Italy.38

It has to be admitted that Caneva had made several good points to his superior. The Italian army in general, and the Expeditionary Force that he commanded in particular, was neither trained nor equipped for desert warfare. This extended to small matters; as Francis McCullagh noted, ‘The water bottle of the French soldier in Algiers always holds two litres. The water bottle of the Italian soldier here does not hold half a litre.’39 This was of no small significance given that the inland oases where the Ottoman forces were located were anything from 10 to 50 kilometres away or, as Caneva had pointed out, a six-hour march at least. In terms of clothing the officers and men wore the low visibility grey-green uniform that had been introduced following the lessons by observers of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5.40 McCullagh, who had also observed the Russo-Japanese War, was unimpressed with its suitability: ‘It is a thick, grey, heavy material, quite hot enough for St Petersburg at this time of year, but absurdly, criminally, out of place here. It closely resembles the stuff used in Ulster for making heavy overcoats.’41

Given that Caneva considered that military operations against the ‘meagre detachments’ of Ottoman forces was militarily beyond the capabilities of his force, he had made the best of his situation by ensuring that the Italian position, particularly at Tripoli City, was as secure as possible. There the thin lines of marines had been replaced with entrenched soldiers, some 37,000 in number, backed up with their own artillery and, ultimately, by the guns of the fleet. The Italian trenches formed a rough somewhat flattened semicircle around Tripoli and its oasis, running south-east from the coast at Fort Sultanje, to the outskirts of the oasis encompassing the wells at Bumeliana. From there they arced back north-eastward towards the coast, touching it slightly beyond Fort Hamidije at a place called Shara Shatt (Sharashet, Shara-shett, Shar al-shatt). The total area enclosed was about 10.5 hectares.

The line between Fort Sultanje and Bumeliana was held by four battalions of Gaetano Giardino’s 2nd Brigade, two from each of the regiments, whilst from Bumeliana to Fort Sidi Messri the 1st Brigade under Luigi Rainaldi manned the entrenchments. From Fort Sidi Messri to the sea, a front of around six kilometres, about 1,800 men of the 11th Bersaglieri were deployed; the 1st and 3rd Battalions were between Sidi Messri and the plateau of Henni, with the 2nd Battalion between there and the sea, based on Shara Shatt. It was to be their misfortune on 23 October to discover that far from being militarily defeated, the Ottoman forces were not only capable of offensive action, but had managed to recruit significant allies. This, and a similar action two days later, and more particularly the Italian reaction, was to profoundly change the course and nature of the war.