The Battle of Tripoli

‘It is true that soldiers sometimes commit excesses which their officers cannot prevent; but, in general, a commanding officer is responsible for the acts of those under his orders. Unless he can control his soldiers, he is unfit to command them.’

H W Halleck, International Law: or, Rules Regulating the Intercourse of States in Peace and War, 18611

THE inability of the Army Expeditionary Force to project its power much beyond the Tripoli oasis prevented any interference with the Ottoman forces outside. Nesat Bey, who based his command at the oasis of Ain Zara, thus had time to assess the situation and to organise and arm the Arab and Berber tribesmen that wished to join the fight against the Italians. Though the numbers of regular army troops available to him vary widely according to source, there were probably somewhere around 4,000 nizams (Regular Ottoman Troops) under his command. This force possessed a small contingent of artillery comprised of four field batteries and two mountain batteries.

Italian inactivity also allowed a potentially weak area in the Italian line to be identified. All the evidence suggests that Caneva, and his political and military masters at home, were labouring under an illusion concerning the attitude of the Arab and Berber population to the occupation. They believed, and honestly so it would appear, that this population was overwhelmingly hostile to Ottoman rule and friendly towards Italy. As one commentator wryly put it:

[T]he Italians had not the slightest idea of how the administration of an occupied territory should be carried out. The General Staff evidently believed in grandiloquent proclamations, and the arrival of the army was signalled by the publication of several proclamations, some of which, if I mistake not, were plagiarisms from Prussian proclamations found in some history of the Franco-German War. […] no adequate measures were taken, either to police the town and its environment, or to picket the outlying villages and hamlets in the palm-groves. […] A descendant of the house of Karamanli was appointed as vice-governor of the town, and some Moslem as the mayor. With these measures the entire staff and army reposed a confidence in the Arab population which, though engaging enough in the simplicity that prompted it, was a culpable weakness in the stern path of war.2

The City and Oasis of Tripoli, and Ain Zara, in October-November 1911. Following their initial landings, and the withdrawal of Ottoman forces to Ain Zara, the Italians dug in around the southern edge of the Oasis of Tripoli, but their eastern line ran north-south within the dense oasis. This was a front of around six kilometres, defended by about 1,800 men of the 11th Bersaglieri Regiment. On 23 October 1911 the Ottoman forces assaulted this line, an attack coordinated with a rising of the people of the oasis. Attacked from front and rear the Italians lost 21 officers and 482 other ranks missing or killed, though the assault did not succeed in totally penetrating their lines and occupying the oasis. The next morning a further assault breached the Italian lines around Kemal Bey’s house, though again did not succeed in a complete penetration. The Italian reaction to The Battle of Tripoli was drastic, and out-of-control soldiery massacred thousands of the oasis’ inhabitants. That the Italian command believed they had come close to disaster is borne out by their response. In an attempt to bolster the strength of the defensive line it was shortened and withdrawn some two kilometres on the afternoon of 26 October. Huge reinforcements were also ordered from Italy. Any Italian illusions that their conquest would be easy were now dispelled. (© Charles Blackwood).

It is difficult to ascertain where this belief originated. McCullagh blames Captain Pietro Verri of the General Staff, who had travelled to Tripoli prior to the outbreak of hostilities. Utilising the pseudonym Vincenzo Parisio, and pretending to inspect the Italian post offices, he had gathered information on the disposition of Ottoman forces and defences and passed this information on to the invasion force. Verri arrived only a week or so prior to the declaration of war however, so any inquiries he might have made would inevitably have been somewhat cursory. In any event, if he did advise that the population would be receptive to an Italian takeover he was to be proved mistaken. Angelo del Boca finds Carlo Galli, head of the consulate general in Tripoli, guilty of much the same attitude. He quotes his communication of 19 August 1911:

Once we have overwhelmed the resistance of the garrison in Tripoli, the small garrisons will fall, nor should we fear in any case that there will be a call for holy war. The coastal population in any case would not answer the call, because it is all too well aware of what a European government can do. And the tribes that might conceivably respond to such an appeal are poor, unarmed, or too distant to present any real threat.3

There seems little doubt that there was in any event a great deal of wishful thinking on the part of the Italian government and General Staff.4 Indeed Senator Maggiorino Ferraris, a former government minister and the proprietor and chief editor of La Nuova Antologia, admitted it in the February 1912 edition of the magazine. He ‘frankly’ acknowledged ‘that the Italian nation was deceived as to the probable attitude of the Arabs towards them, and that the resistance of the latter has introduced an entirely new element into the military situation.’5 In concrete terms though, this deception, this ‘confidence in the Arab population,’ led to some errors in the defensive arrangements of the territory occupied.

The Italian entrenchments encompassed most, though not all, of the oasis of Tripoli, so that immediately behind the greater part of the line, and stretching backwards to the town itself, were a number of villages and hamlets. These were interspersed amongst a large number of gardens, orchards, olive groves, and the like, intersected by sandy roads and winding paths. Earthen walls or hedges formed of prickly pear cactus delineated the roads and gardens, the whole forming what the journalist William Kidston McClure, who visited the area in November 1911, called ‘a bewildering labyrinth.’6 Dotted amid this maze were the dwellings of the local people, and where a number of these were clustered together, usually around a well, there was a hamlet or village.

The Tripoli Oasis. Following the initial landings the Italian entrenchments roughly encompassed the majority of the periphery of the oasis of Tripoli, so that immediately behind the greater part of the line, and stretching backwards to the city itself, were several villages and hamlets. These were interspersed amongst a large number of gardens, orchards, olive groves, and the like, intersected by sandy roads and winding paths. Earthen walls or hedges formed of prickly pear cactus delineated the roads and gardens, the whole forming ‘a bewildering labyrinth.’ The eastern portion of the Italian line was within the oasis however, which allowed the enemy to approach unseen. This part of the line was broken during the Battle of Tripoli (23-24 October 1911). (Author’s Collection).

To the south and west the Italian trenches generally overlooked scrub and desert, meaning that the opportunities for an enemy to concentrate and launch a surprise attack were limited. This had not prevented several approaches being made by Ottoman forces, particularly in the region of Bumeliana, but these had seemingly achieved little. They had, nevertheless, tended to focus Italian attention on that portion of the line. To the east however the Italian defences were within the oasis itself, so that the ground was much the same in front of the lines as it was behind them. According to an Italian officer who was there, the occupied zone in this area was delineated by ‘A wide, sandy track, near which the palm trees thinned out.’7 What this, of course, meant was that it was possible to approach the defences whilst unobserved.

This was the area chosen by the Ottoman forces to attempt to penetrate the Italian lines, the operation being supported by diversions at several other points of the perimeter. Francis McCullagh told of how he arose early on the morning of 23 October and went up onto the roof of his hotel. Two Italian aeroplanes were aloft, and these flew to the south to conduct a reconnaissance mission over the desert. Returning after some thirty minutes they reported that they had observed four Ottoman encampments between 5 and 8 kilometres south of the Italian lines. Numbers of these forces, consisting of both Ottoman regulars and Arab tribesmen, moved forward until they were within visual distance and artillery range of the southern line of defences, though dispersed so as not to offer a favourable target. These manoeuvres caught the attention of the defenders and the Italian artillery, and at least some of the guns of the fleet, fired upon them.8

Meanwhile, concealed by the foliage of the oasis, a large force of regular Ottoman troops, formed of the 8th Infantry Regiment reinforced with Arab irregulars, had approached the eastern flank of the defences and was concentrated facing the line between Fort Sidi Messri to the sea. This was a front of around six kilometres, defended by about 1,800 men of the 11th Bersaglieri Regiment; the 1st and 3rd Battalions were between Sidi Messri and al-Hani (Hanni), with the 2nd Battalion between there and the sea and based on Shara Shatt. Al-Hani was a sandy hill some 50 metres tall topped with a plateau, upon which stood a villa, in some sources referred to as the ‘white castle,’ formerly occupied by an Ottoman official but now used as the HQ of the Regiment. Apart from the position at al-Hani, which was also the location of a machine gun battery, it seems that no great effort had been put into constructing proper defences along the eastern flank. Indeed, several sources state that there were few, if any, entrenchments. This seems doubtful; would the troops have just stood and sat around without any cover? What is beyond doubt, however, is that the eastern flank in general, and the area around Shara Shatt in particular, had been identified by Nesat Bey and his officers as the weakest point of the line.

McCullagh included in his book an account of what happened from a Bersaglieri who survived. According to this informant, one Evangelista Salvatore from Ravanusa, Sicily, he and his colleagues were awakened just before dawn by the sound of the native dogs barking, particularly in that portion of the oasis outside the Italian line. At about 07:00 hrs this cacophony was drowned by the sound of coordinated rifle fire; a large number of assailants had surreptitiously approached through the ‘bewildering labyrinth,’ and opened close-range fire on the Italian positions. Though taken by surprise and outnumbered (estimates of the attackers vary greatly between 1,000 and 6,000), the 4th and 5th companies of Bersaglieri around Shara Shatt might well have held their own, had not another blow been planned for them. As they sought to defend themselves from the frontal attack they suddenly found themselves assaulted from the rear as well. As McCullagh’s informant put it: ‘The Saraceni seemed to rise out of the earth on every side of us.’9

Up to the point of the encirclement of the Bersaglieri most accounts are in broad agreement, but events afterwards were to become enmeshed in deep controversy and violently partisan disagreement. Basically put, the Italian version, one also propagated by those sympathetic to the Italian cause, was that the Arabs of the oasis had treacherously risen and, literally in some cases, stabbed their liberators in the back. The alternative account, which arose mainly from amongst the foreign correspondents based in Tripoli, was that the Ottoman forces had infiltrated the Italian lines and conducted a successful attack on the Italian rear. Whilst this distinction may appear to be academic, and arguments around it somewhat sterile, it was to become the very crux of the matter due to subsequent events. However, there now seems little doubt that the Italian version is correct and that at least some of the inhabitants of both Tripoli and the Oasis joined in the attack and that this had been carefully coordinated. According to Angelo del Boca:

The revolt involved men and women, old people and children, and it was as ruthless as any rebellion that mixed not only xenophobia but also religious fanaticism. The triggering event, though, was the blameworthy behavior of the Italian Bersaglieri toward Arab women.10

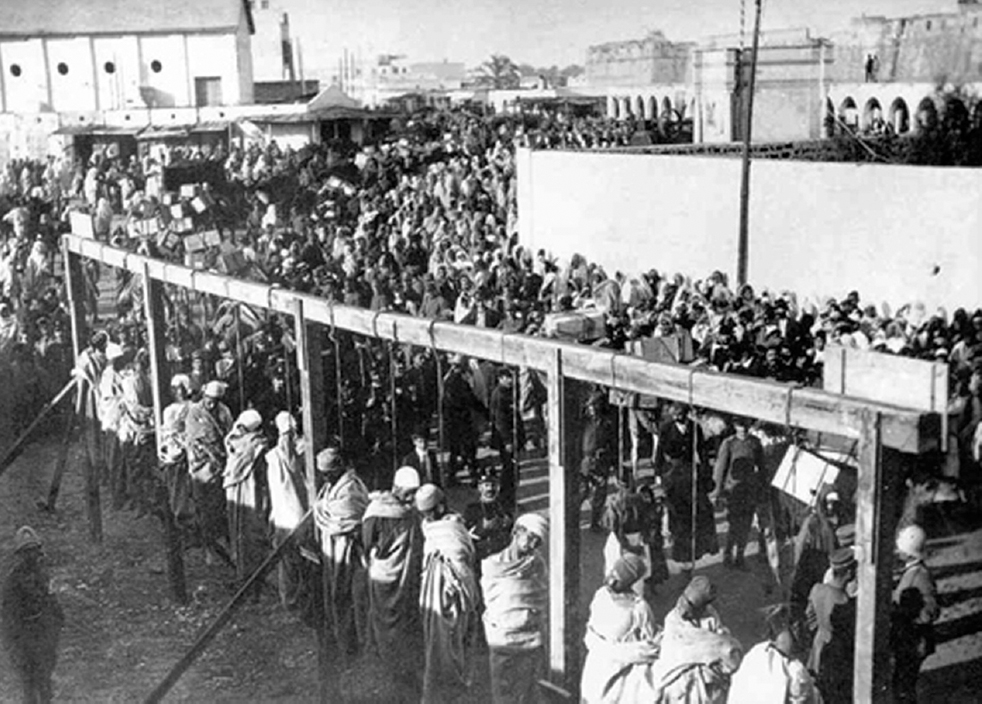

I quattordici strangolati in piazza del Pane (The Fourteen Hanged in the Bread Market) on 5 December 1911. They were: Hussein Ben Mohamed (22); Mohamed Ben Ali (22); Ismail Bahammed el Fituri (20); Mohamed Ben Salemi (50); Ali Ben Sala (50); Ali Ben Hussein (60); Mohamed el-Sium (50); Tahia Ben Tahia (50); Abdul Ben Abdall (45); Allin Ben Gassin (65); Mustafa Ben Glabi (40) and three others whose names are lost. They were seen as the ringleaders of the revolt of 23 October 1911 and were convicted by a court martial on slender evidence obtained from spies and informers. The corpses were left to hang for three days. Paulo Valera, ‘Le giornate di Sciarasciat fotografate’ in Antonio Schiavulli (Ed.), La guerra libica: il dibattito dei letterati italiani sull’impresa di Libia (Ravenna; Giorgio Pozzi, 2009) p. 158. Valera’s work was first published in 1912. (Author’s Collection).

An aerial view of the Italian lines to the southern edge of the Tripoli Oasis. Overlooking scrub and desert there were clear fields of fire, meaning that the opportunities for an enemy to concentrate and launch a surprise attack were limited. Despite this, the Italian line was effectively breached on 24 October 1911 and a number of the attackers, generally considered to be in the region of around 250-300 strong, were able to penetrate into the oasis. However the Ottoman Commander, Nesat Bey, was unable to get reinforcements through the gap due to their approach being interdicted by artillery and naval gunfire. It took the Italians two days to dislodge those attackers who had penetrated the line, with artillery and explosives freely utilised. (Author’s Collection).

There are hints of this ‘blameworthy’ attitude to be found in McCullagh, who recounts an example of a young lieutenant attempting to assist a young woman who had fallen ill, but who was ‘unaware of the fierce jealousy of the Moslems in everything which regards their women.’11 What can be stated with certainty is that, caught between two fires, the men of the 11th Bersaglieri suffered badly and the attackers penetrated the Italian lines and began to fan out. A detachment, mainly of Ottoman regulars, moved to the south to attack the strongpoint at al-Hani, whilst the rest, mainly tribesmen, moved into the oasis. The Bersaglieri HQ at al-Hani was one of the few points in the Italian line through the oasis to be well fortified. It also had a battery of machine guns, making it a formidable position for what were, in effect, unsupported light infantry to attack. Indeed, the Ottoman troops were unable to make an impression and the successful defence of the HQ, under the command of Colonel Gustavo Fara, was, from the Italian perspective, one of the few bright spots of the whole episode. Given it was the only ‘success’ it is unsurprising that Italian propaganda accorded it a level of importance.

Communications between the Italian formations, including GHQ at Tripoli and the advanced HQ at Bumeliana, seem to have failed or been cut, inasmuch as Colonel Fara and his unit were left unsupported for around six to eight hours. In any event there was no general, centrally directed, reserve as all available units were deployed to the defensive perimeter. Two of the three companies of the 2nd Battalion, the 4th and 5th, between al-Hani and the sea were shattered by the attack, whilst the reserve company, the 6th, attempted to fight its way towards Fara’s position. They were severely hampered in this, because the fighters that had broken through the lines now interdicted all Italian movement within the oasis. They had spread throughout it up to the edge of Tripoli itself:

[…] the whole intervening country between the Bersaglieri front and the town was alive with armed Arabs, who shot every uniformed Italian on sight. The roads running from the town to the outposts were naturally full of men on various fatigues connected with supply, and these unsuspecting escorts were the first victims.12

When it was finally realized that a serious battle was in progress on the eastern flank of the occupied zone, reinforcements were dispatched. The nearest were the reserve companies of the 82nd Infantry Regiment (1st Brigade) manning the defences immediately to the right of the Bersaglieri. These had been moved close to the front, lured there by the earlier demonstrations, but eventually one of them, later reinforced by three more, attempted to move to support their comrades. However, they were unable to make fast progress through the labyrinthine terrain and were eventually stopped at the village of Feschlum until evening. By then the attackers had begun to withdraw from the oasis, and it became possible for troops to move around in comparative safety; sniping continued but at a much reduced level. Having held out all day Colonel Fara at al-Hani was then relieved and the gaps in the line were filled.

Several hundred Italians had been killed (later established as 21 officers and 482 other ranks)13 or gone missing during the attack, but what changed the course of the whole occupation was the psychological jolt: ‘It is no exaggeration to say that the events of 23 October shocked the Italian army of occupation from top to bottom.’14 The battle was the first serious fight of the war, and the first in which Ottoman regular forces fought side by side with irregulars, thus dissipating in no uncertain terms all Italian illusions concerning the local population, both inside and outside the zone of occupation. Believing, seemingly genuinely, that his force had been subject to ‘treacherous attacks’, Caneva gave orders the next day that the inhabitants of the Oasis were to be disarmed and, where necessary, punished: ‘[…] ordinary methods of enforcement against the animosity and ferocity of the rebels [being ineffectual] we were obliged to have recourse to severe and energetic measures […].15

What this translated to in effect was a house-to-house search of the Oasis by detachments of soldiers and sailors. Though the Italians, both officially and unofficially, strenuously denied it, this turned into a wholesale massacre of the Arab inhabitants of the Oasis, which, unfortunately for the deniers, was witnessed by the many correspondents present. The massacre of peoples believed, rightly or wrongly, to be hostile to the ruling power, in whatever context, was hardly a novel facet of modern warfare. All powers had been guilty at some point, and the Italians were certainly not the first, and definitely not the last, to indulge in methods of barbarism in furtherance of, as they perceived it, civilisation. From contemporaneous accounts it is probably the case that Caneva and his subordinates lost control of their soldiers:

Caneva and his Staff, however, had not calculated upon what this order meant to troops that had just seen their mutilated dead, who believed that they were again about to be attacked treacherously in the rear, and who had ever over them the shadow of Adowa. The carrying out of the duty necessitated the breaking up of the troops into small detachments, which loosed the control upon the inflamed passions of the soldiery. Nor did the Staff know how or when to place a period upon the licence they thus gave the troops. The result was a retribution upon the Arabs which will live in the memory of the Tripolitaine for generations, and which will react for many a year upon the perpetrators themselves.16

The results were horrific. Thomas E Grant, correspondent of the Daily Mirror, rode through the oasis and his description of what he observed appeared in the 2 November edition of his newspaper:

The two-mile ride to the cavalry barracks was a perfect nightmare of horrors. To begin with, one had to pass a huddled mass of some fifty men and boys, who were yesterday herded into a small space enclosed by three walls and there fired upon until no one was left alive.

It must have been a veritable carnival of carnage. The heap of cartridge cases in the road is evidence of how the execution was bungled. A fellow correspondent witnessed this, and his description of the ghastly scene is too shocking to write down.17

That they did not explicitly order a massacre does not excuse the Italian commanders in general and Caneva in particular. As the American general and lawyer Henry Wager Halleck had stated in 1861: ‘Unless [the commander] can control his soldiers, he is unfit to command them.’18 The principle of Command Responsibility, though the term was not itself used until 1921, had been enshrined in International Law in 1907 under the auspices of the Hague Convention. This entered into force on 26 January 1910 with Italy as a signatory, and thus by not controlling his subordinates properly and allowing the massacres to take place, Caneva had almost certainly violated International Law. This might seem like an academic point inasmuch as there was no authority to prosecute him at that time. In this he was perhaps lucky; Yamashita Tomoyuki, the ‘Tiger of Malaya’, best known for accepting the surrender of 130,000 British Imperial troops at Singapore in 1942, was held to have violated the principle during his trial in 1945, and was hanged the following year.19

Caneva also had other matters on his mind. Fearing further external attacks, he ordered that the defensive perimeter be strengthened. The troops in the oasis were reinforced by marines and sailors, and the personnel from heavy artillery batteries, whose guns had yet to be landed, were pressed into service as infantry. The unloading of field and mountain batteries was expedited and the heavy units of the ‘Training Division,’ the battleships Sicilia and Sardegna to the east and the Re Umberto with the armoured cruiser Carlo Alberto to the west, were anchored close inshore to provide heavy fire support on the flanks. The existing trenches and earthworks were also expanded and reinforced with machine gun positions.

That Caneva’s fears were justified was confirmed by the observations of Captain Carlo Piazza and Captain Riccardo Moizo. Piazza was the commander of the ‘air fleet’ that had become active at Tripoli on 21 October – a ‘fleet’ that consisted of nine aircraft; two each manufactured by Blériot, Farman and Etrich, together with three Nieuports. Piazza had made aviation history on 23 October when he made the first ever combat flight, reconnoitring Ottoman positions during an hour-long sortie. On 25 October Piazza and Moizo, in a Bleriot and Nieuport respectively, observed three columns of enemy troops, which they estimated as some 6,000 men in total, approaching Tripoli from the south.20 Later that day an Ottoman officer approached the Italian lines under a flag of truce and demanded, dependant upon which source one believes, either the surrender of the whole occupied zone, or the eastern area of the oasis. This approach was rebuffed, with the officer allowed to return unharmed.

The first wartime aviators. The airmen that went with the Italian expeditionary force to Tripoli became the first to ever participate in combat operations. Aviation history was thus made on 22 October when Captain Riccardo Moizo performed a reconnaissance flight over enemy positions in a Bleriot. Moizo is second from the right. (Author’s Collection).

Shortly after 05:00 hrs the next morning, Francis McCullagh was awoken in his room at the Hotel Minerva (a part of the Bank of Rome-funded hotel business, Societa Albergo Minerva) by the ‘roar of the naval guns.’ Through the pre-sunrise half-light he saw that the whole of the Italian line was in action but discerned that the firing was heaviest at the eastern side of the oasis around Shara Shatt and al-Hani. Accordingly, he set off through the oasis towards the sound of the guns, noting as he went how empty it appeared following the depredations of the last two days:

I walked along a street of houses which had just been looted and destroyed. I was alone, and the echo of my own footsteps resounded as if I were walking in a tomb. This suburb, so filled with noisy life four days earlier, was now as uninhabited as Pompeii. I did not see a single Arab all the way, nor did I meet with a single Italian.

The oppressive solitudes of the oasis were heavy with a sense of tragedy. The stillness was hostile, the very air was dense with unutterable menace. The shattered doorways and windows gaped like the mouths of dead men. Black with blood and pitted with bullets, the naked walls exhaled the quintessence of malignity and hate.21

A Farman aeroplane at Derna. On 15 October 1911 elements of an aviation battalion, designated the First Aeroplane Flotilla, arrived in Tripoli under the command of Captain Carlo Piazza. He had command of eleven officer pilots, 30 ground crew, and nine or ten aeroplanes: two Blériot, three Nieuport, two (some sources say three) Etrich Taube, and two Farman biplanes. With this unit being the first ever deployed in an active theatre of war, it was inevitable that it recorded several aviation ‘firsts’ whilst carrying out its missions. Aviation history was made on 22 October when Captain Riccardo Moizo, an artillery officer, performed a combat reconnaissance flight over enemy positions. The Second Aeroplane Flotilla was sent to Cyrenaica with three aircraft. To provide reinforcements recourse was made to civilian resources, and eight civilians together with eight army pilots, were deployed to Tobruk and Derna along with nine Blériot and one Farman aircraft. One of the civilians, the sportsman and politician, Carlo Montu, who was given the rank of captain, made aviation history on 31 January 1912 when he became the first casualty of anti-aircraft fire. (Author’s Collection).

If the Ottoman assault at the eastern end of the oasis seemed to occasion the greatest amount of fighting, this may well have been a feint on their part, or they might have been probing for a weak point. If the latter then it was on the south-eastern front that they found it and where a breakthrough was made. Tullio Irace was with the Bersaglieri around al-Hani and he recounted the switch of emphasis:

Towards 9 o’clock the enemy on our front had lost all combined action, and was now carrying on a desultory fight in various scattered detachments under cover of the palm trees. About this time the main body of Turks and Arabs had shifted westward, pressing heavily on the centre of our lines between Messri and Bu-Meliana.22

The weak point revealed was around a position centred on a large two-storey building, known to the Italians as Kemal Bey’s House, which was complete with an overgrown garden totalling a little over a hectare. Situated some 1.5 kilometres to the west of Fort Sidi Mesri (for which the battle is often known, though it is also named Henni-Bu-Meliana in some accounts), this position was held by the 7th Company of the 84th Regiment under the command of Captain Hombert. It appears that the defenders were deployed mainly in the building as a group of attackers, numbering around 250, was able to approach them unseen via the garden. The raiders were able to get into the property seemingly unobserved and, in a near repeat of the events of three days before, take the defenders unawares. There is some evidence that the area had been selected as a potential weak point previously and the defenders subjected to crude, though seemingly effective, attempts at psychological warfare. Amongst the attackers was a British officer, Lieutenant Herbert (sometimes rendered as Harold) Gerald Montagu of the 5th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers. Quite what impelled Montagu, an officer of Jewish extraction, to travel to Tripoli and join the Ottoman effort is obscure.23 He later furnished an account of the preparations for the assault:

On the night before [the attack] six Arabs sallied out of the city with a quantity of cord, with which they secretly looped up a dense plantation of prickly pear bushes, joining up the cords to a main rope, which they entrusted to an Arab urchin of 11 years. During the night the urchin, acting on instructions, pulled the rope vigorously for some time, causing the bushes to rustle. This scared the Italian troops in the vicinity, and they fired on the bushes for six hours, literally blowing the jungle away and leaving themselves without ammunition.24

There is some corroboration of this from the writer and correspondent Ernest Nathaniel Bennett. A former MP for Woodstock and fellow of Hertford College, Oxford, he travelled to Tripoli via Tunisia in late November 1911. Bennett was an experienced hand and the author of several books detailing his experiences. Working under a commission from the Manchester Guardian he joined with the Ottoman forces and the next year published an account of his adventures and observations. During the course of his stay he interviewed several of the participants in the attack, and, according to the stories related to him, the members of the 7th Company were found ‘half-dazed’ and many were ‘roused from sleep merely to die.’25 McCullagh, who got his story from Italian survivors, corroborates this to an extent, relating that during the night ‘there were mysterious and inexplicable tappings and movings in the underwood, and the sentinel’s morbid imagination was crowded by phantom shapes from the blood-curdling folk-lore of Sicily.’ He reported their accounts of how, later, ‘when their ammunition was exhausted, they had been most treacherously set upon.’26 Even if the personnel of the 84th Regiment were drawn from Florence rather than Sicily, it is still possible to visualise their discomfiture and fear. That many were taken unawares is perhaps evidenced by noting that most of the deaths in 7th Company were caused by the curved knives of the Arabs. According to Bennett, these did ‘terrible execution.’27

With the taking of Kemal Bey’s House the Italian line was effectively breached and a number of the attackers, generally considered to be in the region of around 250-300 strong, were able to penetrate into the oasis. Though relatively few in number they were able to cause a great deal of confusion by attacking from the rear the Italian positions on either side of the breach, which were occupied by the 4th and 6th companies of the 84th Regiment. Despite causing around 100 casualties within these troops, the attackers were unable to exploit their success due to the effectiveness of the Italian artillery, both land-and sea-based. In particular three batteries based at Bumeliana were effective, though, as on the 23 October, Italian movement within the oasis was somewhat circumscribed by riflemen concealed in the labyrinthine interior.

Nesat Bey was unable to get reinforcements through the gap in the lines due to their approach being interdicted by the gunfire, supplemented by the fire of the machine guns. Troops, including the 1st and 2nd (dismounted) Squadrons of the Lodi Cavalry from the nearby barracks and eight companies of infantry from the 4th and 40th Regiments supported by artillery, were sent into the oasis in an attempt to clear out those attackers that had managed to pass through the Italian line. It took the Italians two days to dislodge some of these, with artillery and explosives freely utilised. Ellis Ashmead Bartlett, the distinguished correspondent under commission to Reuters, recounted how some 30 of the invaders resisted all attempts at expulsion from several houses at the edge of the oasis until, on 28 October, these properties were demolished with high explosive.28

One enterprising officer, commanding a company of the 82nd Regiment sent to reinforce the front line, evolved a method of ameliorating the difficulties of negotiating the seemingly sniper-infested oasis. Finding that the sniping rendered his movements exceedingly slow, the commander, Captain Robiony, adopted a ‘successful stratagem.’ He collected together some 30-40 Arab inhabitants from their houses, including women, children, and the elderly, and put them at the head of his column. ‘The effect was miraculous. All opposition ceased. The houses, the olives, the palms, the fig-trees ceased to vomit fire.’29 Robiony’s force was thus able to continue unimpeded. Several of the war correspondents present witnessed and recorded this event. Those representing Italian papers, such as Giuseppe Bevione of Turin’s La Stampa, were approving. Most foreign correspondents, Otto von Gottberg of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger for example, differed. The former called Robiony’s act a ‘stratagem that happily succeeded’ [stratagemma riuscito felicemente] whilst the latter commented that ‘neutral witnesses were shocked and outraged’ [Neutrale Augenzeugen waren entsetzt und empört].

Gottberg was to be shocked and outraged further. On the morning of 27 October he was near the cavalry barracks:

Out of an Arab hut, I saw a young woman emerge holding in her right hand the fingers of her little son, and in her left a water pitcher. The street was perfectly tranquil, but suddenly three shots rang out and the woman fell dead. The screaming child fled back into the house. I must admit that the horror of this sight made me stagger and almost fall to the ground.30

The killing of the inhabitants of the Oasis of Tripoli had not ceased since 23 October, but it intensified following the attack three days later. According to Ashmead Bartlett:

[From 24 -27] October […], the troops proceeded to make a clean sweep of all that portion of the oasis of which they held possession. There is no certain proof that any Arabs in the west end of it ever took part in the rising; but, even admitting that there were, there were vast numbers of men, women, and boys who were perfectly innocent, and of these nearly all the men, and even the boys above a certain age, were shot, while undoubtedly many women perished in the confusion […] Although there was no fighting on the afternoon of 27 October, there was continual firing in all parts of the oasis. This was entirely produced by small bodies of soldiers, in many instances without officers, roaming throughout and indiscriminately massacring all whom they met. We must have passed the bodies of over one hundred persons on this one high road, and as similar scenes were enacted through the length and breadth of the oasis some estimate of the numbers of innocent men, women, and children who were butchered, doubtless with many who were guilty of attacking the Italian troops in the rear, may be appreciated.31

Such scenes were witnessed and later reported by many more of the correspondents. There can be no doubt that whilst the attack of 23 October had struck a profound psychological blow, the second breaking of the line was shattering. As McCullagh phrased it: ‘For the Italian army this was near being the end of all things […] a disaster to which Adowa would be as but a street accident, and which the House of Savoy could hardly hope to survive.’32 That he believed his command had come close to disaster is borne out by Caneva’s response to the second attack in particular. In an attempt to bolster the strength of the defensive line he decided to shorten it, and on the afternoon of 26 October he ordered that the eastern flank be withdrawn some two kilometres. This was achieved on 28 October, abandoning Fort Hamidije, Fort Sidi Messri, Shara Shatt and al-Heni to the enemy. In order to hold what he had, take back what he had lost, and to make even modest gains beyond that, Caneva requested large-scale reinforcement, and a second Army Corps was swiftly mobilised. By 7 November another 30,000 men had been deployed within the Tripoli perimeter.

According to ‘Kepi’ these ‘were about the two worst military measures that could have been undertaken.’

The first had a still further depressing effect upon the troops, and gave opportunity to the Turkish commander to report sensational victories to Stamboul. The second will only swell the tale of sickness which must be the lot of this great Italian army cooped up in Tripoli.33

The latter point was well made. Supplying the occupying army and population of Tripoli with potable water was a major concern, as the available wells were not of sufficient capacity. Consequently, considerable quantities had to be shipped from Sicily. In addition the sewage system of Tripoli, such as it was, was unable to in any way cope with the additional strain, leading to the inevitable outbreaks of cholera and dysentery. The military hospitals were kept at full stretch and the mortality rate amongst the troops from the former over the three-month period from October 1911 to January 1912 was in the order of 4-5 men per day.34 It was probably much greater amongst the non-military population though no-one bothered to keep accurate figures. In any event this population had been reduced by the actions of the Italians. There is no reliable figure for the number who were killed between 23-27 October, though many of the foreign correspondents estimated it at circa 4,000. Another 3,425 are known to have been deported by the military authorities to the various island penal colonies, mainly those on Ustica, Ponza, Favignana and Tremiti, as well as mainland prisons at Caserta and the Neapolitan fortress of Gaeta.35 These deportations were in many cases little more than a delayed death sentence. Reports in the L’Ora di Palermo of 8 and 9 November 1911 stated that

‘The conditions on Ustica are now extremely alarming. Because of the Arab corpses tossed into the sea from the steamship S. Giorgio not far from the beach, the fish market has been suspended. […] The burial of other Arabs who died of cholera, in shallow graves in the sand on private property, make easy pickings for stray dogs and constitutes a further menace to the public health.’36

Due to the inability of the Italian authorities to admit that they had ever suffered any military setback whatsoever, a recurring theme throughout the course of the conflict, the shortening of the line was presented as conforming to a manoeuvre already planned. According to Irace:

To give our men a rest and also to make the line of defence stronger for the repelling of possible future attacks, the front of our position near Henni, in the oasis, was slightly altered by withdrawing it about one mile. This change in the front had been deemed necessary since the first days of our landing, when it was soon seen that such an extensive defence-line could not everywhere withstand the enemy’s onslaught when he was in considerable force. By restricting the line it not only becomes stronger, but also leaves more men to act in the reserve and keep the oasis clear, and, moreover, to guard us from fresh surprises in the rear.37

One other effect of the withdrawal was to allow the Ottomans to reoccupy part of the oasis. There was a military side to this inasmuch as installations such as Fort Hamidije and Fort Sidi Mesri, the useful equipment of which was destroyed before evacuation, were recovered. Some five pieces of artillery were either found in, or taken to, the former as an ineffective bombardment of the city was attempted on 31 October. This was swiftly silenced by naval gunfire. However in the oasis itself the Ottoman forces, and particularly the Arabs, then discovered the bodies of their people left by the events of the previous days; one of the reasons Caneva gave for the withdrawal itself was ‘because of the effluvium from the unburied corpses’ and McCullagh says that ‘the oasis stank with unburied bodies.’ The only first-hand account of this initial discovery was by Herbert Montagu; indeed he is credited with being the first to publicise the Italian massacres, as the official correspondents based in Tripoli could not, of course, immediately report what they had seen because of the strict censorship. Montagu’s report, dated 2 November, was sent via Dehibat (Dahibat) in Tunisia and appeared in the London papers on 4 November:

I feel it my duty to send you the following telegram, and I beg you, in the name of Christianity, to publish it throughout England. I am an English officer, and am now voluntarily serving in the Turkish army here. […]

Imagine, then, my feelings when, on entering and driving the Italians out of the Arab houses which they had fortified and were holding, we discovered the bodies of some hundred and twenty women and children, with their hands and feet bound, mutilated, pierced, and torn. Later on at (omitted) we found a mosque filled with the bodies of women and children, mutilated almost beyond recognition. I could not count them, but there must have been three or four hundred.

Sir, is this European war? Are such crimes to be permitted? Cannot England do something to stop such horrors? In our civilisation and times you can hardly believe it, but it is nevertheless true. I myself have seen it, and so I know. Even now we are getting news of further massacres of women and children discovered in different farms lately occupied by the Italians.

[…] The idea of the Italians when they slaughtered these innocents was obviously one of revenge, from the way the bodies were mutilated – revenge for their heavy losses in battle. […] Hoping you will do all you can to bring the barbarous atrocities I have mentioned before the British public and authorities.38

This was, justifiably, treated with some suspicion. Montagu was self-confessedly contravening the 1870 Foreign Enlistment Act, which made it a crime for any citizen of the United Kingdom to enlist in a foreign force. Furthermore as a serving British officer he was in danger of losing his commission in disgrace. However, shortly after it appeared and been denounced as a total fabrication by the Italian government and press, it was corroborated by the accounts of McCullagh and von Gottberg. The latter two had ‘sent back’ their credentials as war correspondents to Caneva on 27 October in order ‘to leave an army in which such things were done.’ W T Stead put it rather more strongly: ‘he refused any longer to be associated with an army which had degenerated into a band of assassins.’39 McCullagh in particular then began a campaign in the UK to alert the British public, and the wider world, to the behaviour of the Italian army in Tripoli. For this he was twice challenged to a duel by Italians, one of them being none other than the founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Marinetti wrote a series of articles for the the French newspaper L’Intransigeant about the attacks of 23-26 October 1911, later published as a book, La battaglia di Tripoli [The Battle of Tripoli].40

The Battle of Tripoli – and the twin battles of Shara Shatt and Sidi Mesri are probably best grouped and understood under one heading – was a major turning point in the conflict and had several far reaching consequences. The Italians were faced with what can only have been the shocking realisation that the Arab people of Tripoli were not, contrary to expectations, waiting for them with open arms. From late October onwards then the enemy, or more particularly the Arab component of that enemy, were considered ‘nonbelligerent fighters’ (unlawful combatants) and either slaughtered or immediately deported according to Angelo del Boca.41 This demonization did not extend quite as far with respect to those who had proven their allegiance to the Italian cause. This included Hassuna Qaramanli who had been proclaimed Vice-Governor of Tripoli at the time of the Italian landing. However, a certain amount of suspicion extended even to him and his situation seems to have been nebulous. Despite his ‘official position’ he was often referred to as the Mayor, and according to McCullagh ‘it does not seem to be quite certain what sort of a tenth-rate honorary position the unfortunate man held’. His prerogatives, such as they were, were circumscribed following the Battle of Tripoli: ‘For the sake of the general tranquillity, the powers accorded to the Mayor of the city have been limited to matters of strict necessity in exclusive connection with local customs.’42

The racial-religious animosity stirred up by the Battle of Tripoli was not confined to the Italians. As Herbert Montagu reported it, ‘the Arabs were maddened beyond all restraint by the outrages in the oasis.’43 This clamour was to spread and the correspondent of the London Times was to inform the readership of that organ on 27 March 1912:

From Tunis to Aziziah [Al’Azizah in Lower Egypt] the country rings with tales of wanton destruction committed by the Italians, of the massacre of defenceless men, and the slaying of women and small children, even children at the breast. […] The longer the struggle lasts, the more men will flock to the Crescent from the interior. The Arab version of the massacre, and of other reported excesses upon the part of the Italians, has now travelled into the desert and the Sudan. Recruits and reinforcements, with promises of more, are daily pouring into camp. El Senussi, the mysterious Sheikh, who wields such power in the interior, has formally declared war against the Italians […]44

The situation following the battle indicated that in both military and political terms Italian strategy had proven a failure if not entirely collapsed; Caneva was to report to Rome on 6 November that the situation was quite different from that which we expected to find when we landed on these shores. It would no longer be possible to take possession of the rest of the vilayet without resort to military methods. There was no obvious means by which this could be achieved in any event, and that the Ottoman forces were possessed of a considerable capacity was now palpable. In other words, there was no quick military solution to the war once the initial landings had failed to bring about an enemy collapse. The situation on the ground in Tripoli was, militarily, at stalemate. Politically and diplomatically the situation was similar, though there were still moves, with varying degrees of risk attached, which were available.