‘The Jaws of the Sahara’

(Le fauci del Sahara)

But around me is a silence of death: a word seems to spring from the horizon: – Back! – Back to all of you who want to violate my secret, you who were not born in my restless dunes, you were not burned by my fire, taught not to wait, against the earth, the passage of my rage … Back! – And these words of challenge rose as knights armed with a deadly struggle, only a few men, naked, implacable as the expanse of sand and the scorching sun … and launched by the jaws of the great desert […]

Domenico Tumiati, ‘Le fauci del Sahara’ in Tripolitania, 19111

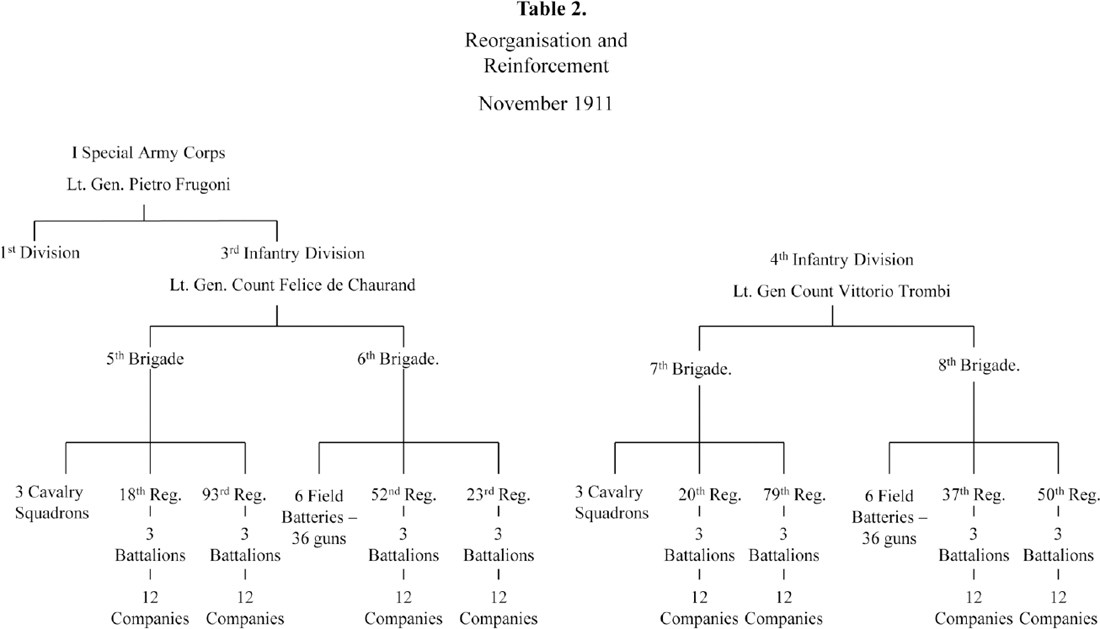

CANEVA’S request for reinforcements was swiftly met with two more divisions being mobilised and transported to Tripoli. The first to arrive on 4-5 November was the 3rd Division under the command of Lieutenant General Conte Felice de Chaurand de Saint Eustache. The 4th Division under Lieutenant General ConteVittorio Trombi, less one regiment, was sent to Cyrenaica where Trombi was appointed as governor of Derna. All in all by around the middle of November 1911, there were some 85,000 Italian troops based in the enclaves along the coast. With the reinforcements came another Lieutenant General, Pietro Frugoni. Frugoni had been the commander of IX Army Corps headquartered in Rome, and it was announced there on 5 November that he had left to take command of the newly formed I Special Army Corps (i° Corpo d’Armata Speciale) formed at Tripoli from the 1st and 3rd Divisions. Caneva though remained as Governor and in overall command of the army of occupation. By 20 November the Italian Army in the vilayet was around 90,000 strong, the main components being 16 regiments of infantry (48,000), 3 regiments of Bersaglieri (9,000), 3 battalions of Grenadiers (3,000), and 4 battalions of Alpini (4,000). In addition there were 12 cavalry squadrons (circa 2,500 men) and the equivalent of 4 regiments of artillery (around 6,000 men and some 200 guns of various types) as well as 5 battalions of pioneers and engineers (4,000). Support troops, including units of Carabinieri, made up the rest.

These, and later additional reinforcements, ensured that the Italian occupation could not be dislodged. However from the Italian politicians’ point of view, stalemate appeared to be leading towards a considerable problem and the longer it endured the greater it became. What haunted the government was the possibility of the Great Powers becoming involved and brokering a peace that would leave Italy without total, undisputed and undiluted, sovereignty over Tripoli. That one or more of the Powers would try to become involved seemed highly likely, as none of them would wish to see the Ottoman Empire weakened. The last thing they wanted was for the Eastern Question to violently erupt and shatter the status quo in several areas. For Austria-Hungary this area was the Balkans, for Britain and Russia the Turkish Straits (The Bosphorus and Dardanelles). France had massive Ottoman financial investments and Germany was also cultivating the Empire; the Berlin-Baghdad railway being an example. Indeed, both Italy’s partners in the Triple Alliance had begun mediation efforts from the moment Italy had delivered the ultimatum. Moreover, as long as the military situation remained stalemated then the greater the likelihood that diplomatic pressure would be applied to the Italian government to come to reasonable terms, with ‘reasonable’ meaning allowing the Ottoman Empire some face-saving device. The historic precedents for this were several; Britain administered and ran Egypt and Cyprus under purely nominal Ottoman sovereignty and had done so for a number of years, whilst the same applied to France and Tunisia and, until 1908, Austria-Hungary and Bosnia.

Initially Giolitti and San Giuliano appeared to favour some such measure, as was signalled by the Prime Minister in a speech at the Teatro Regio, Turin, on 7 October. Though he described the conflict as a ‘crusade,’ he also implied that Italy’s best interests would be served by coming to compromise resolution with the Ottoman Empire to end it. It is arguable that some arrangement with the Ottoman government was, at that time, at least possible. The Grand Vizier Hakki Pasa and his government had resigned upon the outbreak of hostilities, to be replaced by a cabinet headed by Mehmed Said Pasa. The new Grand Vizier indicated in talks he held with the German Ambassador, Baron Adolf Marschall von Bieberstein, early in October that he foresaw a compromise solution. On 4 October he noted the inevitability of abandoning Tripoli to Italian occupation and administration, though under the maintenance of the Ottoman Sultan’s sovereignty. Marschall conveyed these views to his government in a series of telegrams, noting particularly that the new Foreign Minister, Assim Bey, told him on 11 October that the Ottoman government recognised that any residual sovereignty left to the Sultan would be ‘fictitious,’ but that on such a basis mediation by Germany could proceed.2

‘Public opinion’ put paid to such notions on the Italian side. Compromise was anathema to the jingo right and the full force of their invective was unleashed on Giolitti and his government for even hinting at such a thing. Enrico Corradini’s newspaper L’Idea Nazionale predictably viewed any such notion as ‘treachery’ and anything less than Italy dictating peace terms as ‘humiliation.’ The opposition leader Sidney Sonnino was ‘incensed’ by such notions, claiming that anything less than full and outright annexation would be detrimental to Italian prestige.3 Having pandered to ‘public opinion’ in respect of the invasion of Tripoli, the government now found itself the prisoner of it, and by the end of the month Giolitti changed his opinion to match that of the ‘public.’ Though the cliché about riding the tiger springs unbidden to mind, he was later to justify this by the effect it would have on the local population:

Now, even leaving aside the impression on Italian public opinion, the maintenance of the Sultan’s nominal authority in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica had several serious consequences. Such a solution would have reduced much of our authority on the Arab population, who would continue to regard the Sultan as their sovereign as well as their religious leader.4

What Giolitti’s change of mind amounted to in real terms was the issuing of an annexation decree. On 5 November Victor Emmanuel III proclaimed Italian sovereignty over Tripolitania and Cyrenaica:

We have decreed and do decree: Tripolitania and Cyrenaica are placed under the full and complete sovereignty of the kingdom of Italy. An act of parliament will establish the final regulations for the administration of the said regions. Until this act shall have been promulgated, they shall be provided for by royal decrees. The present decree shall be placed on the table of parliament for the purpose of its conversion into a law.5

This was the burning of diplomatic bridges taken to extremes, and there were several consequences. Perhaps the least important was the ridicule it brought upon Italy in the foreign press and elsewhere. The British journalist, W T Stead, put it thus: ‘From the point of view of international law this annexation was as null and void as from the point of view of the actual facts it was grotesquely absurd.’6 The point about international law was well made; according to the respected jurist Lassa Oppenheim, annexation of conquered enemy territory, whether of the whole or of part, confers a title only after a firmly established conquest, and so long as war continues, conquest is not firmly established.7 Under this principle it followed that as long as the Ottoman Empire refused to end the war by negotiation then the war could not end, and whilst this was the case Italy’s annexation would not be recognised by any other powers. The announcement that Tripolitania and Cyrenaica was Italian sovereign territory also led to the curious situation of Italy seemingly carrying out a blockade of her own coastline. Indeed, because of Italian supremacy in the maritime sphere, this duty devolved upon four armed merchant ships, formerly mail steamers each armed with six 150 mm guns, from 10 November. Italy was in danger of looking foolish. However the international press agencies began, from 7 November, to carry messages to the effect that the Italian government regarded the annexation ‘as a second ultimatum.’ If the Ottoman Empire refused to concede on Italian terms then the Italian fleet would be ordered ‘to attack Turkey at one of her vital points.’

Unfortunately for Italian aspirations, the Ottoman government had also had a change of mind. Following the Battle of Tripoli it suddenly became clear that resistance to the Italian occupation was not a forlorn hope. The local population, or at least the significant proportion of it, would fight under Ottoman leadership. The Ottoman military leadership also recognised that the Italian Army was, as currently organised, incapable of winning an outright military victory. They therefore decided to send as much assistance as possible to the forces resisting the Italians. This was no easy task due to Italian command of the sea and the attitude of the British. Cyrenaica shared a frontier with Egypt, which was nominally Ottoman territory under the ‘Khedive of Egypt and the Sudan,’ Abbas II (Abbas Hilmi). On 20 September 1911 Lord Kitchener of Khartoum had left England for Cairo to become agent and consul-general to the Khedive, and it was he who effectively ruled during the time of the conflict. Despite a popular clamour from several sections of the Egyptian population, he was able, in accordance with British neutrality, to prevent any overt large-scale assistance being offered to the Ottomans from Egypt.

Kitchener was often credited with having knowledge of the workings of the ‘oriental mind’ and he seemingly managed the matter diplomatically. When a number of officers in the Egyptian Army asked permission to volunteer to fight against the Italians, he gave the impression that he would not oppose this. However, he warned them that when they returned their positions might not be open and they would have to retire from the army. Similarly, he told the Bedouin chiefs that if they raised levies from their people to fight for the Sultan, then the Khedive would no longer exempt them from conscription into the Egyptian army. Accordingly, neither group went ahead with the idea.8 Similarly, the Ottoman government was denied the use of Egyptian territory for sending materiel or personnel to the war zone. Given the size and nature of the area concerned, and the lack of communications, the appearance of an Ottoman army on the frontier of Cyrenaica was not a realistic prospect in any circumstances.

What was possible was the covert infiltration of individuals and small groups into Cyrenaica via Egypt. This operation was carried out under the auspices of the Teskilat-i-Mahsusa or Special Organisation. The origins of this organisation are, because of the lack of any documentary evidence, obscure. Some accounts trace its origins back to 1903, whilst others argue that it did not come into being until the advent of the First World War. Then it was to become infamous for its role in the Armenian Genocide, as well as being involved in operations in the Caucasus, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Having sifted all the available evidence, the Turkish historian Taner Akcam has concluded that a group of officers associated with Enver Bey began to describe themselves as the Special Organisation, which was founded in order to organise and supply the guerrilla war that was to be waged in the Tripoli vilayet.9

A number of Ottoman officers, totalling 107 according to Stoddart, were to travel surreptitiously to Tripoli and Cyrenaica via Tunisia and Egypt. Several of these were to achieve high status, including Enver Bey, later the Ottoman minister of war and member of the triumvirate that took the Empire into the Great War on the side of Germany.10 Robert Graves was later to memorably, if inaccurately, describe him as ‘the son of the late Sultan’s chief furniture-maker, and a soldier politician who had worked his way up, it was said, by murdering every superior officer who stood in his way.’11

Enver, according to his 1918 account, left the Ottoman capitol in ‘absolute secrecy’ on a steamer bound for Alexandria in Egypt on 10 October 1911. He was in disguise with ‘dark glasses, clean shaven, [and] wearing a black fez down to the eyebrows.’ Nevertheless he feared that he would draw attention to himself and be recognised. This fear was unfounded, but he records that he was feeling depressed about the magnitude of the task of getting to the war zone and fighting the Italians.

The ship arrived off Alexandria at noon on 14 October, but the docks were in quarantine and so the vessel had to moor offshore and await clearance until the next day. After disembarking and passing through an ‘unpleasant half hour’ clearing immigration and baggage inspection, Enver was taken to a hotel by his guide. This guide is identified as one Arif Pasa about whom nothing further is known, though Salvatore Bono has speculated that he might have been the former Governor of Adrianople (1907) and Navy Secretary (1909).12 If so he was of very high rank and perhaps not the best person to meet someone travelling incognito. In any event, Enver seems to have maintained his guise as an academic until 22 October, when he records that he has changed identity and moved to ‘a dirty little room, where a stifling air prevails,’ the gloom of which is only partially relieved by a candle. Feeling depressed by his surroundings Enver went out but records that he had an encounter with the police, who ‘seemed to suspect that I was not the innocent merchant from Syria who I now pretend to be.’

Two days later however he was en route to Cyrenaica by train, travelling third class to avoid being recognised and with ‘an Arab woman with two young children, a German and a Frenchman as travelling companions.’ The journey was not a comfortable one:

Through the sea of sand our little train rolled slowly forward. Heavens, what a train! I feel every part of my body. I’ve just had breakfast: raw dates, that was all. I now need to get used to this diet. […] The desert wind covers us in very fine sand, which penetrates even though the windows are all closed. Our faces and hair are covered with it and it is very unpleasant! It fills the mouth, and one has to swallow it.13

At some point in the journey to the terminus of the railway at Ed-Daba Enver records that he had to change trains for an even more uncomfortable berth in a freight wagon; ‘it was terrible being in there, and it stank such that I could hardly breathe.’ The ordeal was not overly prolonged and after sleeping a night on the train he started the rest of the journey on horseback with five companions and seven horses; ‘Five Arabian horses for me and my comrades […] and two horses for our luggage.’

By 7 November Enver and his small caravan had reached a point some 15 kilometres west of Tobruk. He records that he had ridden 60 kilometres the previous day on a Hegin, the largest and strongest type of camel, which covered the distance in ten hours. During the course of this journey he had carried out a reconnaissance of Tobruk, concluding that there were only two battalions of Italian troops stationed there, and heard of an action five days previously in which an attempt to cut the Ottoman telegraph lines had been repulsed. This arduous journey could not of course have been undertaken without the active assistance of the Arab inhabitants. For example, on the night of 16 November Enver and his companions were at the zavia14 at Unirn er-Rezm, some 10 kilometres northwest of Bomba. He records that they were given a room to stay the night, though there were no beds; ‘the carpets on the floor are the beds.’ Of much more importance though was the allegiance sworn to him as commander of the Ottoman forces by the leaders of the various tribes in the area. This meant, according to his calculations that in two days around 10,000 irregular fighters could be mobilised if necessary.

By 19 November Enver had reached the zavia of Martuba, situated some 20 kilometres south east of Derna on the strategically important caravan route. This was close to his final destination and around 800 kilometres from the starting point at Alexandria. It was the day after he had reconnoitred the defences at Derna:

Yesterday I was very close at Derna. The hostile pioneer trenches [earthworks] lay at my feet, and outside the city was an armored cruiser. The Arabs are happy when they see me. Initially they had been terrified of the shells from the warship but have now realised that the thousands of shots fired have caused no damage or injuries. The Italian advanced positions have been driven back and they do not try further advances. They are afraid of the Arab forces, in bands from 10 to 100 strong, who swarm around them and attack, especially at night.15

The first Ottoman regular officers had arrived by the middle of October 1911 and their influence began to be felt on the character of the war almost immediately as they took over the coordination of military resistance to the Italians. One example of this was the harassment referred to at Derna, with a particularly worrying (from the Italian point of view) probing attack on 17 November. Most notable in retrospect was the presence of Mustafa Kemal, who arrived after travelling through Egypt disguised as a carpet salesman according to some sources, and crossed the Egyptian-Cyrenaican border on 8 December. Some ten days later he reported to Enver, who had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on 12 November 1911 and appointed as commander of the forces in Benghazi.16 Enver accordingly informed the Ottoman War Ministry that ‘Staff Major Mustafa Kemal joined the army at his own request on 18 December 1911.’17

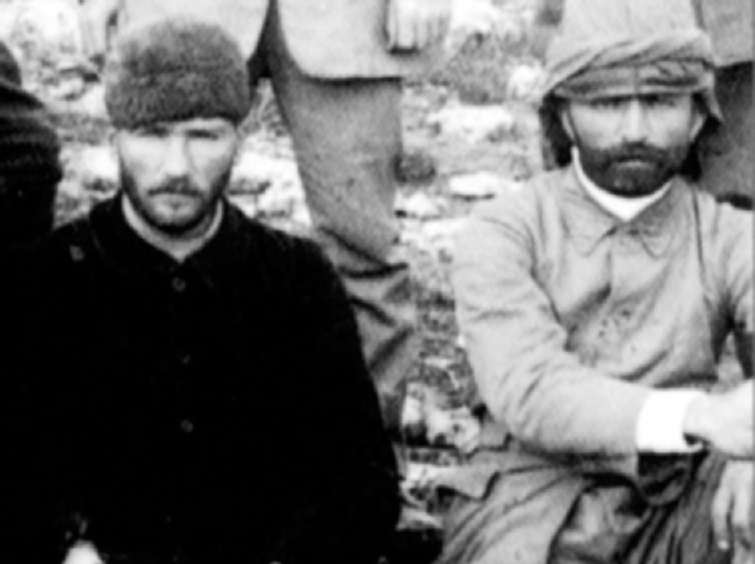

Mustafa Kemal (left) and Enver Bey in the hinterland south of Derna in 1912. Enver Bey (Ismael Enver) was one of the leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) or ‘Young Turks’ as they were known colloquially. He was serving in Berlin as Ottoman Military Attaché when Italy declared war and hurried back home. According to his own account, he persuaded the government to adopt a guerrilla strategy in the Tripoli vilayet and journeyed clandestinely to the theatre to put it into practice as commander in Cyrenaica with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. Headquartered near to the Italian occupied port of Derna, the Ottoman led forces were able to prevent the invaders from venturing beyond their coastal enclaves where they were covered by the guns of their fleet. Major Mustafa Kemal, who joined Enver’s command on 18 December 1911 after travelling incognito via Egypt, initially commanded the Ottoman-led forces around Tobruk. He stressed discipline and order to the men under his command, and divided them into small units. As soon as he arrived he personally reconnoitred the Italian positions and recommended a small-scale attack. This, his first engagement with the enemy, took place outside Tobruk on 22 December, and was deemed a victory. It was though, as elsewhere, impossible to do more than attempt to hold the Italians within their defences. On 30 December Kemal was reassigned to Ayn al-Mansur (Ain Mansur), where he was to command the forces before Derna and Tobruk while Enver commanded the whole Cyrenaican theatre from the same place. (Author’s Collection).

Enver had written on 20 October that the morale of the Arabs was improving and that their understanding that he was related to the Caliph had affected them enormously.18 As early as 4 October Enver had foreseen that countering Italian aggression would be impossible by conventional measures, and argued that a fallback on guerrilla warfare should be made.19 The Ottoman Army had significant experience in counter-insurgency warfare and they used this knowledge, albeit in reverse as it were, to organise the resistance movement, the manpower for which had of necessity to come from the inhabitants of the vilayet.

There was at the time little in the way of a national identity amongst these peoples, though a nascent version was to be forged during the period of resistance to Italian rule. Indeed, one of the local leaders who came to the fore during this episode, Farhat al-Zawi (Farhat Bey), is reported to have told a French journalist who reported from the Ottoman side during the conflict that the population were ‘patriots in bare feet and rags, like your soldiers of the revolution, and not religious fanatics […] if the Turkish government abandons us we will proclaim that it has forfeited its right over our country. We will form the Republic of Tripolitania.’20 Despite this, and his admonition to the same journalist not to write of ‘Holy war’ as it would make the resistance suspect in French eyes, there is no doubt that the backbone of the struggle was indeed religious and based on the Senussi Movement.

The Senussi (also transliterated into English as Sanusiya, Sanusiyyah, Sanusi and Sanussi) was founded by Muhammad bin Ali al-Senusi (1787-1859) in 1837 as a missionary effort among the Bedouin people of Cyrenaica. Initially its rationale was to restore the original purity of Islam and to guide adherents towards a better understanding of it, and to combating alien beliefs and practices. Grounded in the Maliki school of religious law (one of the four schools of religious law within Sunni Islam) it soon advanced towards being a political movement, though it would be a misrepresentation to consider it fanatical or reactionary. According to Muhammad Khalil the movement did not advocate violence or aggression unless provoked and ‘professedly and openly declared that its foremost weapons were ‘guidance and persuasion.’21 This began to change at the turn of the century when Senussi influence reached the southern edge of the Sahara and began to clash with French colonial expansionism. A new leader also arose in 1902 when the grandson of Muhammad bin Ali al-Senusi inherited the title. Under Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif al-Sanusi the Senussi became more politically engaged and started to organise military resistance, principally amongst the Bedouin peoples, against French encroachment from the south.

The ideas and practices of the Senussi, who founded centres of both educational and economic importance, gained traction with the inhabitants of the Ottoman vilayet to such an extent that by the time of the Italian invasion the territories they effectively administered, spiritually and materially, were almost independent of Ottoman governance. The leaders of the Senussi were regarded not just as religious teachers but as leaders who were able to exert both political and religious influence over the various tribes and, crucially, command their respect and allegiance. Knut S Vikør argues that the movement could be considered a brotherhood, which welded the ethnic identity of the Saharan Bedouin and neighbouring peoples into something resembling a proto-nationalist movement.22

One of the few Europeans to come into contact with them was Hanns Vischer, the Swiss-born British colonial administrator and explorer. He became famous for crossing the Sahara from north to south, from Tripoli to Lake Chad, on horseback in 1906. Vischer published an account of his journey in 1910 and made several references to the hospitality he had received from the Senussi, and how they had protected his caravan from brigands. His experiences led him to entertain respect for them and their ways:

I have seen the hungry fed and the stranger entertained, and have myself enjoyed the hospitality and assistance enjoined by the laws of the Koran. My own experiences among the Senussi lead me to respect them as men, and to like them as true friends, whose good faith helped me more than anything else to accomplish my journey in spite of all difficulties.23

Rather presciently he did note: ‘Should, however, the Senussi decide to fight the Christians whose advance into the countries once ruled wholly by Islam they naturally deplore, their number, organisation, and armament would make them a formidable enemy.’24

They remained willing to acknowledge the Ottoman Sultan as their ruler, and Caliph, provided that his government did not in any way encroach upon their autonomy. This nominal allegiance was acknowledged by the Ottoman authorities, who accorded recognition to the Senussi and maintained cordial relations with them. Indeed, as has been pointed out, Ottoman representation in the vilayet was weak and enfeebled and, in reality, largely ineffectual, or, as Rosita Forbes put it: ‘When the Italians landed in Libya in 1911, there existed a kingdom within a kingdom and the Turks were only masters in name.’25

The population that the Senussi sought, and were able, to unite at least to some degree, was around 1.5 million strong and composed mainly of Arab tribes, with a smaller proportion of Arab-Berber and non-Arab tribes.26 Among the non-Arab grouping were the Berber tribes, many of whom had migrated from Algeria and Morocco, and the nomadic Tuareg, the latter being of Berber origin and living mainly in the south-west of Fezzan. There were also sub-Saharan Africans who had in many cases intermarried with both Arabs and Berbers. Those Arab tribes that lived mainly in the desert, and were usually nomadic or semi-nomadic, were collectively categorised as Bedouin.27 There were also a number of Ottoman citizens of different backgrounds numbering around 50,000 mainly from Anatolia, Armenia and Albania. These were for the most part concentrated in urban, or semi-urban, areas and some at least were Christians. Also in the towns were other Christians from Spain and Malta totalling about 17,000, as well as around 20,000 Jews. These latter groups were, in the main, in areas occupied by Italy and in any event would have been immune to calls for resistance based on religious solidarity.

When Italy invaded Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif al-Sanusi (Sidi Ahmed) was at Kufra (Kufara) in Cyrenaica. Kufra is a group of large oases located some 1500 kilometres south of Benghazi and spread over a roughly 200 kilometre long, vaguely crescent shaped, area. Situated in an extremely remote area it had only been described by one European, the German explorer Friedrich Gerhard Rohlfs who had visited it in 1878-9.28 It was however a waypoint on an important trade and travelling route and, since the late nineteenth century, had been the main centre of the Senussi movement, hence the presence of the leader. Lisa Anderson points out that it may have been Enver Bey who personally convinced Ahmad al-Sharif to declare a jihad against the Italians.29 However he was not a dictator and was obliged to call a meeting of the tribal chiefs and adherents and attempt to convince them to join in such a struggle. Given the remoteness of Kufra and the vastness of the area concerned, this council of war, as it may perhaps be called, did not convene until January 1912. According to Abdul-mola al-Horeir, when al-Sharif addressed it he encountered some reluctance as regards fighting, with many at the meeting arguing that the Italians were too powerful an enemy.30 However, he rallied them by sheer force of personality it seems, and reinforcing his argument with apposite Quaranic quotations reiterated that jihad was a duty that had to be carried out against the invaders despite their superior power. He concluded his argument by stating that he would, if necessary, fight the Italians alone, armed only with his staff. This swung the attendees behind him, and on 23 January 1912 jihad was declared and al-Sharif effectively became the leader of the resistance movement. The call was swiftly answered:

In Cyrenaica […] a large number of tribal chiefs and tribesmen, roused by the call, hastened to rally around the Sanusi flag. In the Fezzan, the call to jihad […] met a similarly favourable response. And in Tripolitania, steps were taken for the co-ordination of Arab resistance […]31

Even before any potential manpower deficiency was solved by the religious mobilisation of the population against the invaders, the Ottoman officers were putting into practice what Uyar and Erickson call their ‘de facto strategic plan; they sought to wage a campaign of attritional unconventional warfare.’32 To this end the vilayet was divided into operational areas, with Tripoli and Benghazi being the main ones. In these areas mission oriented units under the command and control of regular officers were formed from the tribesmen, de facto if not yet de jure mujahedin, leavened with regular soldiers and members of the gendarmerie.

Ottoman strategy was then dictated by a mix of Italian predominance at sea, the neutrality of the Great Powers, and Italian conventional military strength in the enclaves it held. On the other hand Italian strategy was, militarily, constrained by its inability to come to grips with the main body of the enemy, and, politically, by the need to maintain the neutrality of the Great Powers. Not offending one or other of these whilst bringing Italian strength to bear at some vital point, and thus forcing the Ottoman government to come to terms, was a conundrum that Giolitti and San Giuliano pondered. Their military and naval advisers had applied their minds to it even before the Battle of Tripoli. Pollio had raised the issue in a letter to his naval opposite number, Admiral Carlo Rocca Rey, on 19 October 1911.

[…] I think it might be useful for us in the current war to occupy some part of the Ottoman Empire that will compel them to accept peace. Unfortunately we do not have a free hand and so we cannot act, for example, on the west-coast of the Balkan peninsula, or, by forcing the Dardanelles, go to Constantinople […] But we can […] take some island, as a bargaining counter at least. Strategically the island of Rhodes would be most valuable, and by taking it we would avoid the pitfalls of acting in the Cyclades Islands or Sporades.33

There would certainly have been pitfalls in acting in the Cyclades; they had been part of the Kingdom of Greece since 1832. Similar considerations applied to the Sporades, or at least the Northern Sporades as they were often called at that time. The Southern Sporades, or Dodecanese as they are now known, included Rhodes and had been Ottoman territory since 1522. Attention was though to turn to them again in 1912.

That the politicians were highly sensitive to the dangers of, even inadvertently, causing an international incident whilst conducting operations outside the main theatre had been exemplified in the Red Sea. The light cruiser Puglia, under Capitano di Fregata Pio Lobetti Bodoni, had been deployed there on 2 August 1911, and on the 5 November (some sources say 3 November) she discovered the Ottoman gunboat Alish hiding at the (now Jordanian) port of Aqaba (Akaba) and sank her by gunfire. This was hardly a major engagement; the Ottoman vessel was a wooden steamer armed with two 37 mm guns. The Puglia returned on 19 November and, in company with the older Calabria, bombarded the port and ancient castle. Despite the paucity and weakness of any potential targets, the navy was ordered to suspend all operations in the Red Sea from 20 November. This was because on 11 November the British vessel RMS Medina had left Portsmouth for Calcutta. Though the vessel had initially been escorted from the harbour by eleven Dreadnought battleships, the majority of the journey was completed under the protection of four armoured cruisers; Argyll, Natal, Cochrane and Defence. The route of these five ships was via Port Said, Suez, and Aden, which took them through the war zone. Aboard Medina were King George V and Queen Mary, whilst the whole was under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Colin Keppel. The King Emperor and his consort were en-route to the 1911 Delhi Durbar, held in December to commemorate their coronation as Emperor and Empress of India. Not until the division had cleared any potential scenes of action, it arrived at Aden on 27 November, did Italian activity resume. On 30 November the Yemeni port of Shaykh Sa’id (Sheikh Said, Cheikh Saïd) the defensive guns of which controlled the southern exit of the Red Sea, was bombarded as was Mocha. On 1 December Khawkah was destroyed and twenty people killed, whilst Mocha, Dhubab, and Yakhtul were again bombarded on 3 December.

In any event, whilst grand strategy was the province of the politicians and military and naval leadership, the men on the ground in the main theatre, Tripoli, had designs of their own to accomplish. These included the recovery of the ground lost after the Battle of Tripoli, and expansion beyond. Frugoni lost no time in utilising the I Special Army Corps attempting the former, and on 6 November an assault, directed by Lieutenant General Conte Felice De Chaurand de Saint Eustache, was made by the 5th Brigade from the eastern trenches with the aim of retaking Fort Hamidije. According to Italian sources, both official and unofficial, this was accomplished without effort and resulted in great losses. As Irace related it: ‘The resistance of the Turks and Arabs stationed there in considerable force was completely futile; and equally futile were their desperate attempts to make a counter-attack with both infantry and artillery, in the endeavour to drive back the Italian brigade. They were repulsed and routed with heavy loss.’34

However, those who were with the Ottoman forces told a slightly different tale. According to the journalist Sir Ernest Nathaniel Bennett, a ‘disaster’ overtook the 93rd Infantry Regiment, elements of which attempted a flanking movement from the sea.35 This amphibious approach, covered by the guns of the ships, saw the troops landed on a beach in the vicinity of Shara Shatt. This move had been foreseen and a large number of Arab fighters deployed to counter it. Some 200 Italians managed to disembark, but they were immediately attacked and very few escaped alive. Five were, however, taken prisoner, and it was from these and Ottoman reports that Bennett got the story. Nevertheless, no matter how many setbacks the Ottoman forces were able to inflict upon the Italian army, they could not resist their attacks backed as they were by superior artillery and naval gunfire.

Fort Hamidije was accordingly retaken by 7 November, and the next day more ground was recovered around the Tombs of the Qaramanli. This high ground, which included a large Arab graveyard, an ancient tomb containing the remains of a holy man, and two domed buildings accommodating the Sarcophagi of the Qaramanli, lies on the flank of any advance towards Fort Hamidije. Heavy rain, ‘which converted the trenches and rifle-pits into pools, and made the movement of guns or ammunition-carts almost impossible,’ then forced a suspension of offensive operations for over a fortnight. According to one eyewitness, The Times correspondent, William McClure:

Lakes formed in the desert and remained all through the winter, while the main torrents burst through the trenches at Bumeliana, drowning one soldier, seriously damaging the waterworks, and pouring down the Bumeliana road till the streets of Tripoli were a foot deep in swift-running water.36

It was only on 26 November that conditions had moderated enough for operations to be resumed. The main direction of this attack was to be easterly within the oasis. The assault was to be made by de Chaurand’s 3rd Division and the objectives were Fort Sidi Messri in the south, al-Hani in the centre, and Shara Shatt next to the coast. Fort Sidi Messri was to be assaulted by the 6th Brigade (23rd and 52nd Regiments) under Major General Conte Saverio Nasalli Rocca, reinforced with the 50th Regiment from the 4th Division, which had been held back from Cyrenaica. Supported by four batteries of artillery this force was to advance along the southern limits of the oasis, with its right flank protected by cavalry. The thrust on Shara Shatt was to be made by the 5th Brigade (18th and 93rd Regiments), whilst the centre was to be assaulted by an ad hoc force consisting of the Fenestrelle battalion of Alpini, the 11th Bersaglieri Regiment, and two Grenadier battalions. The whole operation was supported by artillery and the naval guns of the ‘Training Division.’

In order to shield the attack the 1st Division kept a defensive watch on the southern side of the oasis in case any substantial attempt at reinforcement was made by the Ottomans. As an extra precaution a demonstration was made to the south, with a force estimated to be in the region of 5,000 strong. Moving in two columns the Italians advanced only about a kilometre and their behaviour puzzled observers. George Frederick Abbott later reported what had transpired: ‘[…] the Italians crept on, digging trenches at every one hundred metres - admirable tactics for defence, but for an advance purely imbecile. Finally, as the sun was setting, they began to beat a retreat.’37 Their tactics, however apparently imbecilic, had succeeded inasmuch as they had fully engaged the attention of the Ottoman forces in the desert and at Ain Zara. This prevented any reinforcement of the forces in the oasis where, despite their overwhelming superiority, it was slow going for the Italians. The difficulties of the terrain made the combat akin to fighting in a built up area, and many of the Ottoman strongpoints had to be demolished with explosives. However by about 16:00 hours most of the ground that had been vacated following the Battle of Tripoli had been retaken and the troops were consolidating their positions. Their casualties had been comparatively light, somewhere around 120-160 officers and men killed and wounded dependent upon source, but the operation gave rise to another controversy.

Whilst searching the ground that they had retreated from on 23 October the Italian troops made a grisly find. The journalist William Kidston McClure, who was on the Italian side of the lines, related what he heard and what he saw.

Three bodies were discovered first, in a garden a little to the north-west of El Hani, three crucified and mutilated bodies. […] On the evening of [27 November], about fifty more bodies were discovered, indescribably mutilated, and some of them bearing obvious traces of torture. Early on the morning of 28 November, I visited an Arab house and garden, which had been used as a posto di medicazione (advance field hospital) by the 2nd battalion of the 11th Bersagheri, up to and during the fight of October 23. In the house there were five bodies, in the garden nine, and in a hollow at the back of the house, beside a well, there was a ghastly heap of twenty-seven bodies. […] No object would be served by detailing the record of human savagery displayed by those dreadful remains, the crucifixion, torture, and mutilation that had been practised upon living and dead. One case will suffice as an illustration, the case of a body which was identified by means of a pouch as that of a stretcher-bearer attached to the 6th Company of the Bersaglieri. His feet were crossed and his arms extended: he had clearly been crucified. There were holes in his feet, but his hands had been chopped off. His eyeballs appeared to have been threaded laterally by thick, rough palm-twine, and his eyelids were stitched in such a way as to keep his eyes open. In addition he had been shamefully mutilated.38

There were other foreign correspondents that were brought to witness these terrible scenes and who subsequently reported them to the wider world. One of these was Gaston Chérau (Leroux), author of Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (translated into English as The Phantom of the Opera in 1911), correspondent for Le Matin. His report appeared in the 30 November edition of the paper under the sub-heading Horribles tortures infligées par les Arabes aux bersagliers prisonniers ou blesses (Horrible tortures inflicted by the Arabs on the Bersaglieri prisoners and wounded), and was extremely graphic:

I was present at the interment of the mortal remains of many Italian soldiers who had fallen prisoners into the hands of the Turks and Arabs, and been by them barbarously massacred. These Bersaglieri who fell on October 23 died not merely as heroes, but also as martyrs. I cannot find words to express the horror which I felt to-day, when we discovered these luckless remains in an abandoned graveyard […]

In the village of Heni, inside the Arab burial ground, had been perpetrated an absolute butchery. Of the eighty ill-starred men whose bodies we discovered there, there is no doubt that quite half had fallen alive into the enemy’s hands, and that all had been carried to this place, surrounded by walls, where the Arabs knew they were safe from Italian bullets. There took place here the most vile and loathsome carnage that can possibly be imagined.

The victims’ feet were cut off and their hands torn from their bodies. Some of them were crucified. The mouth of one was split from ear to ear; a second had his nose sawn off; others had ears cut away and nails torn out by some sharp instrument. Finally, there is one who has been crucified and whose eyelids have been sewn up with pack-thread.39

The unfortunate stretcher bearer also featured in the account of Bennet Gordon Burleigh, the circa 71-year old veteran correspondent for The Daily Telegraph in the 26 November edition of the paper:

It was near the mosque by the Henni I had my attention called to the bodies of those who had fallen into the hands of the fiends of the desert. Five soldiers, Bersaglieri, had been tied to a wall, crucified as on a cross, and afterwards riddled with bullets. It is needless to dwell upon the nature of the further atrocities which savage Muslims invariably practise on the bodies of Christians. A sergeant had also been crucified, but with the head down, and in the hands and feet were still left enormous nails.

A little farther away from this mosque a field hospital had been rushed, and every one put to torture and to death – doctors, hospital attendants, and wounded Italian soldiers. Bodies had been torn asunder, faces hacked, and limbs struck off as well as heads. […] But worst of all was this. A hospital attendant under the Red Cross, named Libello, of the sorely tried 11th Regiment Bersaglieri, who also had been crucified, had first had his upper and lower eyelids perforated and laced with tightly tied coarse string. Each eyelid was then pulled, and the cord being tied behind his head, the eyes were held wide open, and could neither be blinked nor closed in life or merciful death. Flies and insects abounded. The look of unutterable horror on the strained face of Libello will remain fixed for ever before me.40

In many ways the discovery of the unfortunate Libello and his comrades was a blessing for the Italians and their supporters; they now had a counter to the accusations of massacre and uncivilised behaviour levelled at them. Accordingly, and as with the massacres, the atrocities committed on the Bersaglieri were either played up or pooh-poohed according to the disposition of the commentator. Those who were pro-Italian used the incident as evidence of the barbarity of their opponents in general. McClure, for example, noted that one of the bodies had been ‘treated in a manner which is more familiar to those who have seen Turkish handiwork in Armenia and Bulgaria than to those whose experience has been confined to Arab practices.’41 Similarly, the Italophile Richard Bagot, who had never visited Tripoli, delivered his judgement in 1912: ‘these unnamable atrocities were committed, at the direct instigation and approval of Turkish officers, and in some cases actually perpetrated by Turks […].’42

In the 1880s Manfredo Camperio, the president of the Milanese Società di esplorazioni commerciali in Africa, had asked ‘How dignified, good, and interesting is the Libyan race! Who would have the courage to disturb these primitive people in their tranquil, pastoral life?’43 Some thirty years later, and whatever the precise identity of the perpetrators, ‘these primitive people’ had, from the Italian soldiers’ perspective been transformed into beasts (belve); the enemy had become inhuman (disumano).44 This perspective translated into popular culture also. The Italian poet Gabriele d’Annunzio produced ten poems, Canzoni per le gesta d’Oltremare [Songs of Overseas Deeds], published in the Corriere della Sera from 8 October 1911 to 14 January 1912. These celebrated the war while it was happening and depicted it as a racial and religious crusade. Indeed, according to Lucia Re:

The Christian rhetoric of the crusades is evoked in the description of the fight against ‘the infidels,’ who are depicted not only as vicious and inhuman beasts, but as ethnically and biologically unchangeable, animals destined to be locked in the inhumanity of an everlasting, unsurpassable barbarism. Eternally treacherous, bloody, and barbaric, they are doomed to replicate their sacrilegious and cruel acts over and over whenever their race is again confronted with the Christian world.45

If d’Annunzio be thought somewhat highbrow, then Carolina Invernizio, one of the most popular Italian writers of the early twentieth century might be considered. Her 1912 novel Odio di araba [The Hatred of Arabs] was set in Tripoli and contains a prologue which outlines her perspective:

‘We are in the trenches of the eastern oasis of Tripoli at Sciara-Sciat on the morning of 23 October 1911, a fatal date which will remain a shining moment of glory in the history of Italian bravery, and will also mark the vile Arab attack, their ambush, their inhuman betrayal, while our sons were still trusting their acts of submission, and were convinced that they intended to surrender. How little did they know the true character of the Arabs, who […] are the most despicable, deceitful, treacherous, ungrateful beings in the world! Their cruelty has no limits, their pride is boundless. […] The hate that the Arabs feel for us and everything European is in their blood and depends not only on the horror which the Christian religion provokes in them, but also on the instinct which keeps them from any modification in their customs, in their clothing, in their life-style.’46

With this irrevocable breach the last strand of Italian pre-war strategy was broken, and all hopes for a short victorious war shattered. They could not, without extending the war into other theatres, force the Ottoman Empire to sue for peace. On the other hand, arriving at a compromise peace that would allow the Ottomans to cede the vilayet with some saving grace had, because it was domestically unacceptable, been rendered impossible by the decree of annexation. Italy was thus forced to remain in a seemingly open-ended conventional war, with all the consequences this entailed, whilst simultaneously conducting another, unlimited and hugely expensive, asymmetric colonial campaign against a population that was now viewed as irrevocably alien and hostile. Wishful thinking still prevailed to a certain extent; the French and British authorities in Tunisia and Egypt were blamed for not preventing ‘the trade in contraband of war’ across the frontiers. If this ceased, and the encouragement and interference of Ottoman officers was prevented, then the ‘tribes from the interior will come and submit to their new masters when they realise that famine is at the door, as they are sure to be overtaken by that formidable scourge.’47

In the meantime however the ‘tribes from the interior’ – ‘implacable as the expanse of sand and the scorching sun’ in Tumiati’s words – remained a defiant and potent force. It was in an attempt to curb their potency and drive them further back into ‘the jaws of the Sahara’ that Frugoni, having completed the recovery of the territory lost during the Battle of Tripoli, intended to take the fight beyond.