The Italians Advance

Tripoli, topographically and climatically, is an impossible country to invade.

Charles Wellington Furlong in The New York Times, 4 May 1912.1

ON 5 November the Italian authorities released a statement, the contents of which were, intrinsically, of little moment. Nevertheless the document is of historic importance, containing as it does the first official communication ever made pertaining to an operation by aeroplanes in warfare.

Yesterday Captains Moizo, Piazza, and De Rada carried out an aeroplane reconnaissance, De Rada successfully trying a new Farman military biplane. Moizo, after having located the position of the enemy’s battery, flew over Ain Zara, and dropped two bombs into the Arab encampment. He found that the enemy were much diminished in numbers since he saw them last time. Piazza dropped two bombs on the enemy with effect. The object of the reconnaissance was to discover the headquarters of the Arabs and Turkish troops, which is at Sok-el-Djama [Suk el Juma].2

Italian military aviation, as in all states that pursued the matter, had begun with lighter-than-air craft – balloons. Pre-unification Italy could boast at least one pioneer in this regard in Vicenzo Lunardi, who had first flown in London on 15 September 1784 whilst stationed there as secretary to the Neapolitan Ambassador. Following his return to Naples Lunardi made several ascents, including one from Sicily in July 1790 that lasted two hours.3 Pre-unification Italy also had the distinction, if that is the correct term, of being the first target to be subjected to aerial bombardment. During the Austrian campaign to reduce the Republic of San Marco in 1849, the city of Venice was invested by Austrian forces. During the final stages of the conflict a novel expedient was attempted by the besiegers. According to Lieutenant General Gugliemo Pepe, the Commander-in-Chief of the forces of the Venetian Republic, they developed a scheme to utilise ‘balloons and other aerostatic devices.’

After talking of these for two or three months, and after numerous experiments made in the Austrian camp near the Adriatic, and in that of Isonzo, they at last carried them into execution. They sent up some fire-balloons from their war-vessels stationed in the Adriatic, and opposite the Island of Lido. These went high enough to pass over that island, and the enemy flattered themselves that they would arrive and burst in the city of Venice; but not one ever reached so far. Under these balloons was a large grenade full of combustible matter, and fastened by a sort of cord, also filled with a composition, which, after a certain given time, was to consume itself. As soon as this happened, the grenade fell, and in its fall burst against the first obstacle which it struck. Of all these balloons that were sent up, one only left its grenade in the fort of St. Andrea del Lido. The others were all extinguished in the waters of the Lagoon, and sometimes sufficiently near the capital to amuse the population more than any other spectacle.4

The Italian Army gained a balloon detachment in the 1880s, with the 3rd Engineer Regiment, based at Rome, forming a company-sized aeronautical section on 6 November 1884. This ‘Aerostatic Section’ (Sezione Aerostatica), under Lieutenant Alessandro Pecori Giraldi, was equipped with two balloons purchased from France. The first manned flight of one of these took place on 7 November when Pecori Giraldi ascended to several hundred metres. The capability of the Aerostatic Section was demonstrated in the field in Eritrea in 1887-8, when three balloons were successfully utilised. Italian military aviation took further steps forward in 1894 with the inclusion of the section into a specialist brigade (Brigati Specialista) and the construction in 1908 of a dirigible, semi-rigid, airship which first flew on 3 October that year.5 Designed and flown by two engineering officers of the specialist brigade, lieutenants Gaetano Arturo Crocco and Ottavio Ricaldoni, this craft was designated N1. Constructed at a base at Vigna di Valle on the southern shore of Lake Bracciano (Lago di Bracciano), its maiden flight saw it journey from Vigna di Valle to Rome and back. It covered the distance, some 70 kilometres in total, at an average speed of about 60 kph flying at an altitude of around 500 metres, and was the first aircraft ever to fly over Rome.

In terms of heavier-than-air craft, the first aeroplane flights in Italy were undertaken by the French aviator Léon Delagrange, who established several duration records there in 1908. On 23 June he flew continuously for 18 minutes 30 seconds at Milan, and on 8 July at Turin he took Thérèse Peltier aloft as a passenger, making her the first, though some sources argue second, woman to fly in an heavier than air machine. On 13 January 1909 a triplane, the first aircraft of wholly Italian construction, rose from the grounds of the Royal Palace at Venaria Reale near Turin. Designed and built by the automobile engineer Aristide Faccioli the flight was only partially successful inasmuch as the machine crashed and was severely damaged. This did not discourage Faccioli however, who went on to reconstruct the craft and design several more.

More reliable types were introduced to Italy in 1909 by the Wright brothers, who were invited to Rome by the head of aeronautics of the Special Brigade, Major Massimo Mario Moris. Moris had travelled to France to meet the brothers and invite them to bring an aircraft to Italy, which would be bought, as well as to train Italian officers to fly. The Wrights arrived at Centocelle near Rome (now Aeroporto di Roma-Centocelle) on 1 April 1909 and began assembling their ‘Wright Model A Flyer’ aircraft. Several notable persons, including King Victor Emmanuel, attended the demonstrations, which began on 15 April, and on one flight a cameraman was taken aboard producing the first motion picture taken from an aircraft. Between 15 and 26 April 1909 the Wright aeroplane performed 67 flights and carried 19 passengers aloft. Two officers, Lieutenant Mario Calderara of the navy and Lieutenant Umberto Savoia of the army, were trained by Wilbur Wright to operate the aeroplane; the former, having more experience, completing the training of the latter. The following year, on 17 July 1910, army aviation was reorganised as a separate battalion of the Special Brigade under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Vittorio Cordero di Montezemolo. New equipment and facilities were ordered; six new Crocco-Ricaldoni dirigible airships, ten foreign-built aeroplanes (2 Bleriot, 2 Nieuport, 3 Farman, and 3 Voisin) and two new airfields, at Somma Lombardo (at Varese in Lombardy) and Mirafiori (at Turin in Piedmont).6

On 15 October 1911 elements of the aviation battalion, designated the First Aeroplane Flotilla, arrived in Tripoli under the command of Captain Carlo Piazza. Under him were eleven officer pilots, 30 ground crew, and nine or ten aeroplanes: 2 Blériot, 3 Nieuport, 2 (some sources say 3) Etrich Taube, and two Farman biplanes. A further three aeroplanes were sent to Cyrenaica. The Tripoli unit became active on 21 October at a site, a narrow field, near the Jewish Cemetery (Il cimitero degli Ebrei) just to the west of the city on the coast. The construction of hangars to hold dirigibles was also begun. The force had been extemporised at somewhat short notice; the decision to furnish the expeditionary force with an aviation component had only been made on 28 September.7

With this unit being the first ever deployed in an active theatre of war, it was inevitable that it recorded several aviation ‘firsts’ whilst carrying out missions. As has been related, aviation history was made on 22 October when Captain Riccardo Moizo, an artillery officer, performed a combat reconnaissance flight, albeit apparently on his own initiative, over enemy positions in a Bleriot. The first official flight was though made the next day, with Piazza flying west along the coast to Zanzur before returning – a mission lasting over an hour. The same day Moizo flew a mission double that length, with an observer, in a two-seater Nieuport. Moizo recorded another first on 25 October when he became the first pilot in history to have his aircraft hit by anti-aircraft fire. The dangers of enemy fire, whilst not to be discounted, were however comparatively slight compared with the perils of flying over the desert. Treacherous and unpredictable air currents, combined with the possibility of sand storms, made such an enterprise innately hazardous, whilst the inherent unreliability and fragility of the first aeroplanes and their engines only served to multiply the danger.

A Taube monoplane at Tripoli City, or at least the fuselage and tail section. Presumably the wings have yet to be attached or have been removed for some reason. Designed and built in Austria-Hungary in 1909 the Taube (Dove) was heavily utilised in the aviation forces of the Triple-Alliance as well as, to a lesser extent, further afield. It has two significant aviation ‘firsts’ to its credit; the first bombing mission (1 November 1911) and the first air to air combat (28 September 1914). (George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress)

Captain Moizo’s aeroplane. Having made aviation history by being the first person to perform an aerial reconnaissance mission in a combat situation and then, less fortunately, becoming the first aviator to have his craft hit by ground fire, Riccardo Moizo was to chalk up yet another first. On the morning of 10 September 1912 he took off from Tripoli in a Nieuport monoplane which, whilst over enemy territory, suffered an engine failure. He was forced to land near Azizia and was swiftly taken prisoner by Arab forces. This photograph, which appeared in the French newspaper L’Illustration on 5 October 1912, shows his craft together with some formally attired Ottoman officers posing alongside. (Author’s Collection).

Another ‘first’ came on 1 November 1911 when 2nd Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti dropped four ‘bombs’ on enemy positions at Ain Zara (Ainzarra) and Tagiura (Tajura) from a height of 600 metres. These devices had been designed and manufactured at the San Bartolomeo torpedo establishment, a part of the great naval arsenal at Le Spezia. Named for their inventor, Naval Lieutenant (tenente di vascello) Carlo Cipelli, granate Cipelli (Cipelli Grenades) were fabricated from thin steel into a sphere weighing about half a kilogram when filled with picric acid. The grenades had fabric ribbons attached which, when air-dropped, provided a ‘parachute’ effect and helped to neutralise any horizontal travel. The presence of the ribbons led to them being nicknamed ‘ballerinas.’ They were difficult to deploy as a firing cap had to be inserted into them immediately prior to use; not an easy task for a solo pilot. Other, similar, ordnance available was of Norwegian origin though manufactured in Denmark. Designed by Nils Waltersen Aasen, who is generally credited with creating the first functioning hand grenade, the device was fitted with a cloth skirt attachment. It was armed by a long cord that burned through as it was thrown or dropped. Consequently, as a contemporary British source stated it: ‘The chief property of the Aasen grenade is that it cannot explode prematurely during the first 11 yards [10 metres] of its flight, for the safety pin is only withdrawn after the burning of a strip of wool, 11 yards long, with which it is secured.’8 According to some sources, the Italians had seized a consignment of these weapons during the course of their blockade. The British airman and author, Edgar C Middleton, was to write in 1917 that ‘the war in Tripoli was of immense advantage to the Italians both in the matter of experience and development in aerial warfare.’9 Epitomising this reflection was the development of purpose-built bombs and devices for launching them from aircraft. An artillery officer, Lieutenant Aurelio Bontempelli, constructed finned cylindrical bombs containing explosive and shrapnel that could be launched through a tube affixed to the aircraft fuselage. In the early stages of the conflict, and certainly during November 1911, the Italian aviators had to make do with what they had or could contrive whilst they learned, or invented, techniques of air warfare.

These included the difficulties of photographing or bombing accurately from the air, which was rendered problematical due to the nature of the machines they were flying. According to an account by Piazza, the camera was mounted under the pilot’s seat, and, as the nose of the aeroplane prevented a clear view of the ground under a given angle, the target became invisible as it was approached. In order then to take a photograph, or indeed drop a bomb, it was necessary to calculate the length of the interval between losing sight of the objective and being in a position to photograph or hit it. Presumably after a good deal of trial and error, the interval between no longer seeing ‘the point to hit and the instant in which to drop the bomb,’ or trigger the camera, was calculated at 35 seconds whilst flying at an altitude of 700 metres at a speed of 72 kilometres per hour.10

The pilots usually flew their machines at an altitude of between 600 and 800 metres but, as they discovered, the range of the Ottoman Mauser rifles when fired vertically was some 1700 metres. Consequently, the aeroplanes were frequently hit by fire from the ground, Moizo merely being the first to encounter this. Inevitably there came a time when the fire from the Ottoman Mausers hit one of the aviators. This occurred on 31 January 1912 when a two-seater Farman piloted by Captain Giuseppe Rossi and with one of the volunteer airmen, Captain Carlo Montu, as ‘bombardier’ took off from Tobruk. Their mission involved reconnoitring an enemy encampment some 30 kilometres distant and testing the Aasen grenade. According to Rossi’s report:

We flew at an altitude of 600 metres and had covered 15 kilometres when we spotted the first group of Arab tents. These welcomed us with such a volley of accurate fire that I had half a mind to give up continuing the mission. But I immediately felt ashamed of my timidity and headed directly toward the Turkish camp, giving my companion the first signal to make ready the bomb, which had to be suspended over the side for dropping.

At 100 metres away from the centre of the camp I gave the second signal to Montu to drop the bomb and, to observe the effect, I turned immediately to the left. I saw a thick dust cloud rise from the ground and people, horses and camels scattered in every direction. It was a wonderful sight: the bomb had erupted with the intended effect. But the joy of this perception was severely impaired by the incessant crackle of the volley of fire aimed at us. I endeavoured to escape from this by turning to the right, but had to turn away again after seeing that this would take me right over the enemy camp. I steered back to the left, only to discover to my horror that a bullet had struck my aeroplane. I tried to climb but was unsuccessful, and so was passing over the left side of the camp when my companion shouted that he was wounded. I had turned around to look at him when the engine stopped and we began to descend. Happily it started again, but we were struck by two more bullets.

The engine was causing me great difficulties and to add to my misfortunes the wind, which was unfavourable, began to drive me off course. The Arabs never ceased firing for a moment whilst my machine hung in the air swaying as if in pain and almost stationary in the wind. I had an engine that was unreliable and feared that Montu might be fatally wounded, and that if he was no longer in control of himself he might unbalance the aeroplane. I expected death every minute but we managed gradually to return to our headquarters, when Captain Montu’s injuries were attended to. He was not fatally wounded.11

Captain Montu, the President of the Aero Club of Italy and the commander of the volunteer airmen at Tobruk, thus became the first ever casualty of ground to air fire in the history of warfare.12 Despite the experience of Rossi and Montu however, aeroplanes had already proven remarkably difficult to damage with rifle fire, and they had consequently become extremely useful to the Italians. This had been exemplified when Frugoni deployed all his airborne assets, both in reconnaissance roles and attempts at ground attack, during the advance to Ain Zara of 4 December 1911, where the enemy were estimated to number several thousand. Ain Zara in Italian hands would become an outpost giving advanced warning of any manoeuvres towards Tripoli and the coast that might be made by Ottoman forces. It would also protect the flank of Italian movements and communication eastward from Tripoli, particularly with regards to the coastal town of Tagiura (Tajura, Tajoura) situated on Cape Tagiura, which it was intended to advance to through the oasis. Tagiura was situated at what may be considered the far eastern extremity of the Oasis of Tripoli. The verdant area between Tagiura and Tripoli, some 18 kilometres in length and 5 kilometres wide, was described in 1817 as ‘a tract of coast […], which abounds with palm trees.’ Little had changed in the intervening period, though the population of Tagiura that had then been enumerated as about three thousand ‘chiefly Moors and Jews’ was now greatly expanded by anti-Italian forces.13 Amongst these was one of the officers that had managed to travel to Tripoli; Ali Fethi Bey (Fethi Okyar) an Albanian and the former Ottoman Military Attaché in Paris. Fethi had his HQ at a place named Suk el Juma, so called because a market was held there on Fridays. This consisted, unsurprisingly, of a large marketplace and little else. There were however some shops on one side of the marketplace, whilst facing them on the other were two government buildings where the Ottoman HQ was established. The war correspondent for Central News, Henry Charles Seppings Wright, visited the HQ which he described as being ‘right under the guns of Tripoli.’ He described the work there as dangerous, and communication between it and Ain Zara difficult because ‘the alertness of the Italians render[ed] it unsafe to ride there during the day.’ Travelling at night was preferable, because ‘one can get through without having to dodge big shells.’14 Just to the north of Suk el Juma was the village of Amruz (Amruss), described as being ‘surrounded by gardens, and containing many habitable houses, in which the Turkish soldiers were comfortably lodged.’15

Tripoli and the occupied zone, together with the hinterland to the south, following the advance to Ain Zara. After the arrival of substantial reinforcements and the formation of the I° Corpo d’Armata Speciale (1st Special Army Corps) the occupied zone around Tripoli City was expanded somewhat. Ain Zara was taken in early December 1911. The eastern portion of the Tripoli Oasis was also occupied, and the Ottoman forces withdrew. Initially they went to Azizia, some 40 kilometres to the south-west, but once the Italians began strongly fortifying Ain Zara moved their main position some 20 kilometres to Suani Ben Adem. Untrained for, and ill-equipped to wage, desert warfare the Italians were unable to make any further substantial advances for the duration of the conflict. Their enemy, consisting largely of irregulars unable to wage conventional warfare, could not eject them from their entrenched positions. The result was deadlock. (© Charles Blackwood).

Ain Zara is a small oasis about 6.5 kilometres south east of Tripoli, at which the Ottoman forces had, to some degree, concentrated; Nesat Bey had his headquarters near there some 5 kilometres to the south. The oasis itself was described by the British journalist Alan Ostler, who was employed as a war correspondent for the Daily Express. He travelled to Tripoli via Tunisia and spent several months with the Ottoman forces and their commander. According to Ostler, Ain Zara consisted of:

[…] a short street of tents along the side of a sandy hollow. Horses, tethered in a line behind the tents, snuffed the ground for stray grains of barley. […] At the bottom of the hollow, disposed in a sort of square, were barley sacks and camel saddles, boxes of cartridges, and three light waggons taken from the Bersaglieri only a few days ago. They were commissariat wagons, with the numbers of their companies and the name of the regiment stencilled in white upon their sides.16

Around the oasis, and screened from view from the north by sand ridges, were ‘many scattered villages of tents’ including one where the Ottoman cavalry were bivouacked. Further out to the west there were also two fenduks (fendukes, fondouks), Fenduk Sharki and Fenduk Gharbi.17 Fenduk Sharki was about one kilometre away from Ain Zara and had been converted into a hospital, over which flew the flag of the Red Crescent. The whole area, including the hospital, was within range of the Italian naval artillery. George Frederick Abbott, who had ‘decided to join the main Turkish and Arab forces in the desert round Tripoli town, with the object of collecting material for a book on the campaign,’ later wrote that the patients of the hospital, ‘while waiting for the overworked surgeon to dress their wounds, amused themselves by squatting under the arched gateway and watching the Italian shells swish in the air, burst, and drop, digging deep pits in the ground around them. Some of these projectiles dropped on the hospital itself, despite the Red Crescent flag that flew over its roof.’18 Nesat had around 700 regular troops, including 60 cavalrymen and about 1,500 irregulars under his command as well as eight artillery pieces. In terms of supplies, particularly food, they were reasonably well off. Fethi Bey remarked to Ostler that, ‘No doubt it pleases the Italians to picture us as starving in the desert, but before they bring us to that stage, they must cut off our line of communication. And, as yet, they have not ventured inland beyond the range of their own naval guns.’19 The Italian reinforcements had though included heavy artillery, and for the advance on Ain Zara, Frugoni utilised batteries of 152 mm guns and 203 mm howitzers emplaced at Messri and Bulemiana. These batteries were certainly capable of reaching most of the Ottoman positions.

Italian Trenches at Ain Zara. Though probably a posed photograph, it illustrates well the difficulties the Ottoman forces faced in attempting to attack the Italian positions. Essentially composed of irregulars, the attackers might at best be classed as light infantry with little in the way of artillery to support them. On the other hand, the Italian forces had abundant artillery further supported by naval gunfire so long as they remained within range of the coast. When the Italians did advance inland they did so in such strength as to be irresistible, which had the concomitant effect of rendering their manoeuvres ponderous in the extreme. The advance to Ain Zara, a small oasis about 6.5 kilometres south east of Tripoli, on 4 December 1911 exemplifies this. Under the cover of artillery support from both naval and land-based guns, more than half of Frugoni’s i° Corpo d’Armata Speciale were deployed; the 1st Infantry Division enlarged by a third brigade and extra artillery. The objective was taken, but the enemy forces easily escaped. (Author’s Collection).

The nearest of these were around three kilometres from the Italian line and consisted of trenches and other excavations. The left of the Ottoman position was to the south-west of Bulemiana and was composed of trenches, described by Abbott as ‘primitive ditches following the up-and-down, in-and-out curves of the dunes, and providing very indifferent cover.’20 These had been augmented by shelters dug into the sand behind the trenches, though connected to them by zigzag saps, and roofed over with planks covered with sand. Each of these could provide shelter for about ten men, protect them from shelling, and conceal them from accurate observation from the air. Manning these defences were around thirty regular soldiers and about two hundred Arab irregulars under a lieutenant; their only heavy weapon was a German manufactured machine gun, probably an MG-09, the 7.65 mm export version of the Maxim machine gun. Farther to the east about opposite to the Tomb of Sidi Messri at some three kilometres distance, was a battery of three field guns and about twenty regular infantry under the command of a captain. Some three hundred irregulars were stationed to the south-west of this position, whilst to the south-east was another field piece opposite Fort Sidi Messri. A further battery of four guns was positioned just to the north of Ain Zara. Curiously both sides were armed with Krupp field artillery; the Italians had the 75 mm 1906 model and the Ottomans the 87 mm 1897 model. The range of the latter was however much inferior. Other than the troops, regular and irregular, mentioned above, Nesat had another similar sized body in front of Ain Zara and a fourth positioned some four kilometres to the west, which included some cavalry.

Frugoni’s plan was relatively simple. Under the cover of artillery support from both naval and land-based guns he would attack using more than half of his i° Corpo d’Armata Speciale, or, in other words, overwhelming force. The manoeuvre was structured around the 1st Infantry Division under Lt. Gen. Count Conte Guglielmo Pecori Geraldi, which was enlarged by a third brigade and extra artillery. The battle was to be fought by brigades; on the left was the 1st Brigade under Rainaldi, augmented by the 93rd Regiment from the 5th Brigade of de Chaurand’s 3rd Infantry Division. The task of the strengthened 1st Brigade was to operate within the oasis to the east, and apply pressure to the Ottoman forces there in order to fix them in position and prevent them manoeuvring or redeploying; the 93rd Regiment being tasked with advancing on Amruz. This would prevent the forces in the oasis from interfering with the main Italian forces operating to the south, or indeed vice-versa. Earmarked with a special duty in this regard were two battalions of the 52nd Regiment from the 6th Brigade, stationed at Fort Sidi Messri under Colonel Amari. Amari’s command was not part of the operation in the oasis, but was, if necessary, to advance from Fort Messri to interdict the road from Ain Zara to Suk el Juma should the enemy attempt to move any of their forces along it.

The other two brigades were to advance in column; the centre column, consisting of an ad-hoc Mixed Brigade (Brigata Mista), was commanded by Major-General Clemente Lequio. This brigade was formed from the 11th Bersaglieri Regiment, one battalion of Alpine Troops (the Fenestrelle), and the 2nd Battalion of Grenadiers (granatieri), together with supporting mountain artillery. With his left flank protected by Rainaldi and Amari, Lequio’s objective was Ain Zara itself, upon which he was tasked with approaching directly. This would hopefully fix the defenders in position whilst the right-hand column, the 2nd Brigade under Giardina, with two squadrons of the 15th Light Cavalry Regiment (Cavalleggeri di Lodi) on his extreme right, attempted to flank the defences and circle around behind the oasis.

In all, about 15,000 troops were to take part in the advance to the south, whilst another 3,000 or so were engaged in the oasis. Several field and mountain artillery batteries were in direct support, whilst the newly-landed heavy guns and howitzers, and the naval artillery aboard the ships, offered more distant support. The terrain over which the Mixed and 2nd Brigade were to advance was such as to make it almost impossible to conduct conventional military operations. Charles Wellington Furlong described the conditions and the difficulties they caused as follows:

It is a land essentially of shifting sand dunes, into which the narrow boots of the Italian soldiers sink deeply, and which can only be traversed by sticking to narrow, winding trails between sand mounds, which average thirty feet [nine metres] and which are sometimes ten times as high. The winding trails are only as broad as a city street. The columns of the Italian army of invasion can’t deploy or spread out in open order. The men in front are picked off as they come up on the Arabs, who lurk behind the dunes or who – a favourite trick with them – bury themselves in the sand so that even their heads cannot be seen.

Cavalry movements are impossible in such a country, and no artillery larger than a three-pounder or machine gun can be drawn. All food, water and even fodder must be transported by the invading army, because there is no such thing as ‘living on the country’ in Tripoli. The only places where vegetables, fruit and water can be obtained are the oases. And the Arabs take care that there is little left in the oases for the enemy to live on. All the fruit and vegetables are taken away and dead camels or mules are thrown into the wells to pollute the enemy’s water supply. The only method of transportation which is practical in that country is by camel. But the Italians have no camels, the Arabs having been careful to leave none behind them.21

The ground between Tripoli and Ain Zara was even more hazardous, being intersected with wadis; dry, and not so dry, riverbeds. Indeed, the night of 3-4 December had seen severe rain and there was a heavy storm at daybreak. Accordingly it is somewhat paradoxical to note that because the rains had filled many of the riverbeds, as well as creating several deep pools, one of the potential dangers faced by those advancing into the desert was drowning. One particularly large wadi that had been in flood since the advent of the rains, wadi Mejneen, was to mark the demarcation line between the two brigades; the Mixed Brigade to the east and the 2nd Brigade to the west. The latter, deployed in column by regiments, had the furthest distance to travel and set off first when the sun rose at about 08:05 hrs, preceded by the cavalry. The central column deployed into marching order shortly afterwards, with the Bersaglieri in the van and the Alpini bringing up the rear, and began moving due south. It was a stormy morning, but the weather that soaked the troops was not bad enough to prevent flying over the desert, which wore ‘a look of desolation most depressing in the morning twilight’ according to Irace who was with the Bersaglieri. He wrote in heroic terms of ‘Captain Moizo’s aeroplane flying on the storm against the lurid background of the great clouds which the wind whirls and twists.’ Moizo, who had attached the Italian national flag to the rear of his craft, was not merely there to raise the morale of the damp soldiery. When he spotted concentrations of the enemy he attacked them. According to Irace again:

[…] we see him circling in great sweeping rings over a special point, like a hawk which has sighted its prey below. Five minutes more and we mark in the far distance, rising from the ground one after the other, in a straight line right ahead of us, eight towering black columns of smoke, like gigantic solitary trees sprung up by magic on the horizon. The master of the sky has sighted the enemy’s trenches and bombarded them, vanishing shortly afterwards towards Ain-Zara.22

Whether Moizo, and his fellow pilots, were responsible for the ‘towering black columns of smoke’ is debatable. Because they had very small charges and tended to bury themselves in the sand before exploding, the grenades utilised were largely ineffective unless they dropped amongst a group of people. As the Ottoman forces had learned to scatter upon the approach of an aircraft, the pilots concentrated on what they could see and, according to some sources, Fenduk Sharki, being large and therefore obvious was a favourite target.23 The soft sand also mitigated the effects of the heavy artillery shells; these sometimes penetrated to the depth of a metre or more before exploding.24

Though the fire of the heavy and naval artillery would have been the most damaging had it been able to hit its target accurately, this was rendered problematical because it could only fire indirectly. As an aid to spotting, a captive observation balloon (drachen-ballon) was sent up from one of the ships to a height of some 1300 metres. From this lofty position the observers were able, to some extent, to correct the fire of the big guns. What would have made a real difference were using aircraft for this service. However, whilst they were eminently suited for the task, they lacked any means of real time communication, or near so, between the aviators and the gunners. Thus observers in aircraft could only communicate by landing to deliver a report, or dropping weighted notes in small metal containers, either of which meant flying away from whatever was being observed. Guglielmo Marconi himself was to argue that whilst the aeroplane had ‘demonstrated in Tripoli its usefulness for scouting purposes in wartime’ this usefulness would ‘be greatly multiplied if the aeroplanes could carry wireless telegraph instruments and operators so that information gathered on scouting trips could be instantly communicated to the operating forces.’25

To counter the Italian advance Nesat ordered the troops stationed to the west of Ain Zara to advance and cover the left flank of the trenches in front of Bulemiana. He also ordered the guns near Ain Zara to advance and support the defenders facing Sidi Messri, but great difficulty was encountered in moving them across the desert and each needed ten pairs of horses to drag it through the sand. It took three hours to get three of the guns forwards and these, together with about fifty regulars, were positioned slightly to the west of the extant battery.

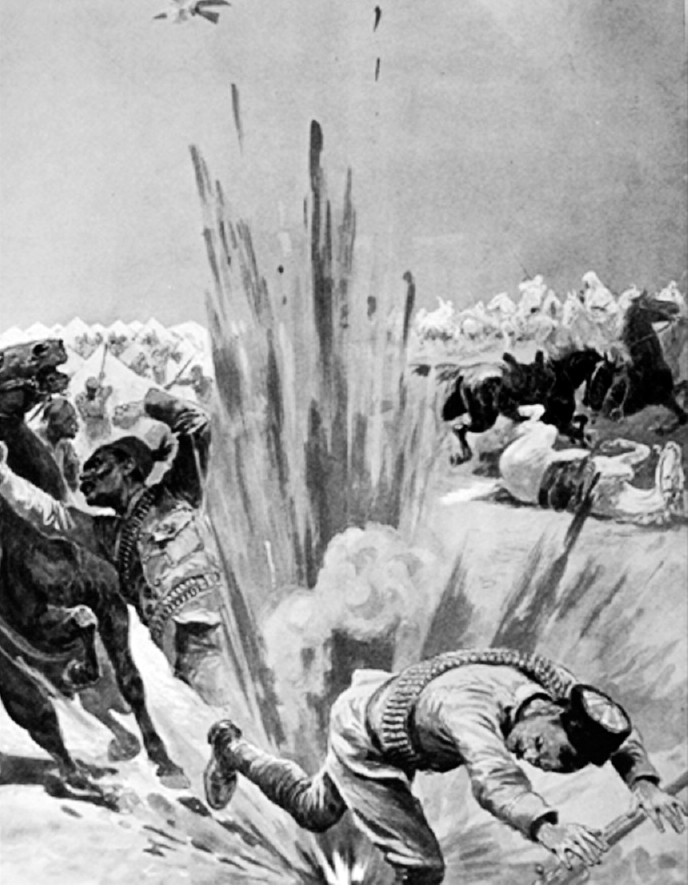

‘The New Arm’s Fearful Strength: Death from the Air’: this drawing appeared in The Illustrated London News on 13 January 1912 and was derived from a sketch made by Henry Seppings Wright. Despite the effects depicted, he was to write that ‘bombs from the aeroplanes were small; quite sufficient to create a scare, but not so deadly and destructive [as those launched from dirigibles]. Also the great elevation at which they flew presented the camp as a very small target.’ The first ever delivery of ordnance from an aeroplane occurred on 5 November 1911. (Author’s Collection).

With these reinforcements the Ottoman front was about 5 kilometres wide and manned by approximately 500 regulars and 1,000 irregulars. The Italian infantry advanced slowly and carefully under the cover of the overwhelming artillery superiority that the pitifully few Ottoman guns could do little to counter. Ordinarily Ain Zara would have been about two hours march from Tripoli, but it was some four hours later that the position on the right of the Ottoman line, its commanding officer having been killed, began to give way and the troops to retire leaving their dead and carrying their wounded. With the left retiring, the centre of the line had also to give way and begin to fall back slowly.

The Ottoman infantry, though forced from its first line of trenches, did not quit the field but rather fired at the Italian infantry from whatever cover could be found. However, as Irace put it, ‘They cannot long resist the fire of our artillery and the menace of the enveloping movement.’26 The enveloping movement by the 2nd Brigade had indeed forced the Ottoman left to give ground, whilst the reinforcements sent by Nesat had become entangled with the Italian cavalry and were also forced to retreat. In withdrawing the Ottomans were required to abandon their artillery through an inability to tow the guns away. One observer reckoned that it took no fewer than 19 horses to drag a gun through the desert sand. This problem also affected the Italians, though they had a way around the worst of it in the shape of mountain artillery.

Attached to the army in Tripoli were three groups (gruppi), each of three batteries, of mountain artillery. The 2nd (Mondovì) and 3rd (Torino-Susa) groups were part of the 1st Mountain Artillery Regiment (1° Reggimento Artiglieria da Montagna), whilst the 2° Reggimento Artiglieria da Montagna had provided its 3rd (Vicenza) group. These artillery regiments formed the organic artillery component of the Alpini, the army’s mountain warfare force. Incongruous though it might appear, the Alpini had extensive experience of operating in North Africa. The 1st African Alpine Battalion (1° Battaglione Alpini d’Africa) had been formed in 1887 and campaigned in Eritrea and Ethiopia. The mountain artillery were equipped with the 70 mm Cannone da 70/15, which weighed nearly 400 kg when assembled, but could be broken down into four loads for transporting by mule.27 The ammunition was also loaded onto mules. The mobility conferred allowed the 2nd Brigade to emplace mountain guns under Colonel Besozzi on a large dune to the southwest of Bulemiana and, from roughly 14:00 hrs, direct enfilade fire onto the enemy positions to their east. Under fire from two directions, the Ottoman forces facing the left of the Italian advance were obliged to retire southwards.

The Italian infantry moved forward as the Ottomans began to retreat, though they did not press hard. By this time the 2nd Brigade and the cavalry were advancing to the west of the wadi Mejneen and Nesat at Ain Zara perceived that his forces were in danger of being encircled, and ordered a general retirement to the south west in the direction of Kasr Azizia some 40 kilometres away. As he later explained to Abbott:

There was nothing else to do. When I saw the enemy coming on - regiment after regiment -my only thought was to save my men. I feared the Italians might take it into their head to send a regiment round our left, and take us all prisoners!28

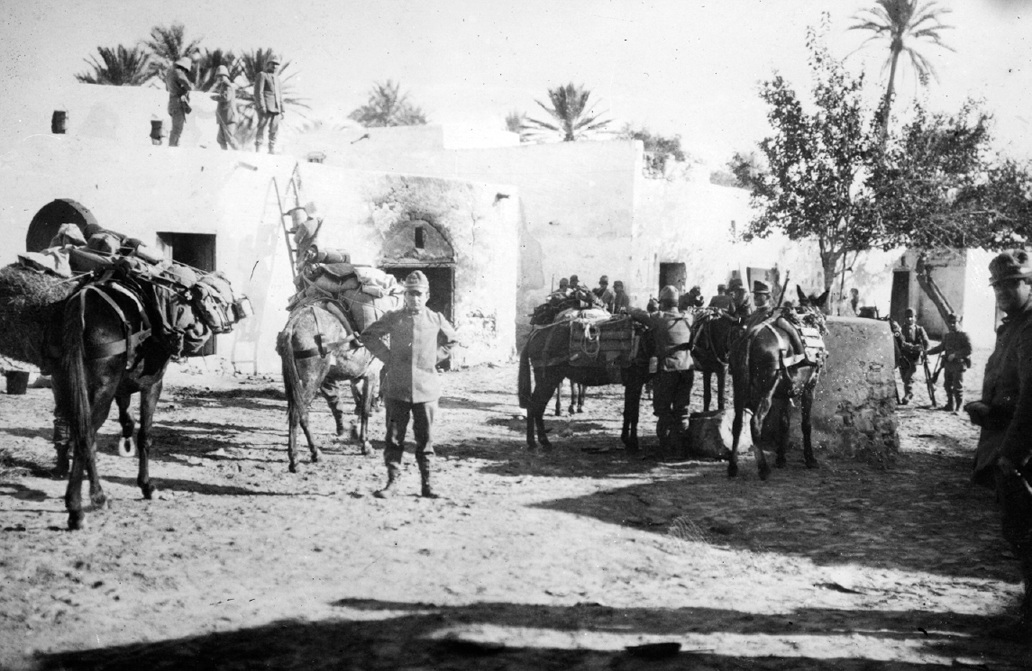

Attached to the army in Tripoli were three groups (gruppi), each of three batteries, of mountain artillery, which ordinarily formed the organic artillery component of the Alpini, the army’s mountain warfare force. The possession of such weaponry - guns that could be broken down and transported on the backs of mules or camels – proved invaluable due to the desert terrain. Field artillery was extremely difficult to move with up to 19 horses required to drag a single piece through the sand. (George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress)

At about 15:00 hrs the majority of the Ottoman forces had conducted a fighting withdrawal towards Ain Zara. However, a previously unengaged contingent that had been stationed some 6.5 kilometres to the west of Tripoli, near Gargaresh, and had been summoned by Nesat, appeared near the wadi to the west of the oasis. Seemingly oblivious to the presence of the 2nd Brigade, or that his command was in its path, the commanding officer led his men towards the wadi until he was intercepted by a messenger who warned him of the situation. This information must have caused the officer to panic, as instead of taking up a position whereby he could impede the advancing Italian brigade, if only for a time, he instead led his command in a dash southwards. According to Abbott ‘he was the only Turk who on that day failed to do his duty, and he was subsequently cashiered for his incompetence.’29 Not that it would have made any difference, for there was no, or very little, fighting between the infantry of the two sides. Whenever the Italians encountered resistance, and the Ottoman forces sniped at them incessantly, rather than engage in infantry attacks they made the defenders retreat by bombarding their position.

The vast majority of the Ottoman forces being irregular, they had their families and other non-combatants camped around Ain Zara. The order to retreat obviously applied to them too, but as Ostler discovered they seemed reluctant to up sticks:

Beyond the ridge that shelters the greatest of the many scattered villages of tents, I came to the straggling encampment of the Arab women, children, and camp-followers. Here were the markets that supplied the army with fodder, meat and flour, and milk and eggs. Already the market was afoot, and the thoughtless Arabs chattered and haggled and brawled, heedless as ever of the rumbling guns; though here and there upon the crests of the rolling dunes sat groups of men intently watching clouds and rings of smoke far to the north. At little distances, too, upon the ridges, sentinels in Turkish uniform kept watch upon the fight, but in the hollows noisy Arab commerce ruled the day.30

It was one of the local leaders, Suleiman el Barouni, who with his colleague Farhat al-Zawi had been a deputy in the Ottoman Parliament, that roused them: ‘The Italians have come against our left in thousands; but on the right we still hold them back. I go to Suk el Juma.’ One of the reasons el Barouni went to the HQ of Fethi Bey was to order or help organise the Ottoman retreat from the Oasis of Tripoli, where the retreat order also applied. With Ain Zara in Italian hands Ottoman communications with their forces in the oasis would be effectively severed. The 1st Brigade had not made much headway in penetrating the Ottoman-held part of the oasis due to the difficulty of the terrain. Italian artillery preponderance was of much less utility when they were fighting in what was, effectively if not actually, a built up area with its ‘maze of deep, tortuous lanes, winding among gardens and groves, the trees and enclosures of which afforded ample cover to the defenders.’31 Elements of the brigade, supported by marines – ‘men in white’ landing from warships32 – had managed to get forward along the coast, avoiding the worst of the ‘maze,’ nearly as far as the Ottoman HQ at Suk el Juma, a distance of 5 kilometres or so. But being unsupported on their right flank through the inability of the rest of the brigade to advance, they could not consolidate, and were forced back to their original position.

Nor had the two battalions of the 52nd Regiment under Colonel Amari had an easy time of it. They had advanced from Fort Sidi Messri to interdict the Suk el Juma-Ain Zara road as per plan, but had come under fire from their own artillery. They took some casualties and their advance was halted whilst a messenger was sent back to the fort. When they resumed their advance they were opposed. Abbott got the tale from ‘Ismail Effendi, a middle-aged Lieutenant of infantry – the Turkish officer in command at that point:’

I was stationed in the Fenduk Jemel, opposite Fort Sidi Misri, on the Ain Zara road, with fourteen Turks and two hundred Arabs. An Italian regiment attacked us furiously, shouting ‘Hurrah! Hurrah!’ and drove us out of the fenduk. Then my Arabs made a counter-attack, yelling ‘Allah! Allah!’ and forced the Italians to fall about one hundred and fifty metres back. These attacks and counter-attacks went on till evening, and at sunset the enemy withdrew into their trenches. About an hour and a half later we made an offensive reconnaissance to see if there were any Italians in front of us or not. We found the field deserted and covered with knapsacks, water-flasks, caps, shovels, rifles, and cartridges. We picked up as much of the loot as we could, and returned to the fenduk, where we rested and slept till midnight. About an hour after midnight two horsemen came to tell us that the headquarters had moved from Ain Zara to Ben Gashir, where we were ordered to follow at once. We could not make out why.33

Nesat’s order to withdraw was also greeted with something approaching incredulity at Suk el Juma. Like Ismail Effendi’s command, they were unaware of the precise nature of the events to their south and had similarly more than held their own against the Italian attacks. Accordingly, those Arab irregulars who were so minded refused to obey and remained in the oasis. The others moved along the Ain Zara road, which of course remained open, and joined the exodus, first to Ben Gashir, around 28 kilometres south of Ain Zara, and then a further 31 kilometres to the south west to El Azizia (Kasr Azizia, Al’Aziziyah). The forces at Ain Zara had begun to retreat at about 16:00 hrs and, rather remarkably, this manoeuvre was carried out in a leisurely manner, at least by the regulars. Abbott likened their attitude to that of:

[…] an East End mob going home after a day on Hampstead Heath. There was no hurry […] The soldiers just strolled away, passed Ain Zara, and got to the headquarters. The first to arrive there were the artillerymen with some of their horses, but without any artillery. The infantry followed. Then came the Staff officers.34

This would have been leaving it too late had not the 2nd Brigade swung eastwards towards Ain Zara at about 15:30 hrs, more or less at the same time as the Mixed Brigade was approaching the oasis from the north-west. From the peak of some of the higher ridges around the place they were able to see the last of the fighters and the camp followers evacuating the place in a disorderly mass. Ostler, who was with them, described the sight thus:

The retreating columns marched across sands now glowing rosy in the sunset [sunset was a little after 18:00 hrs]. Belated Arabs straggled beside the ranks of marching Turks. Arab women, carrying huge loads, staggered wearily through the loose sand, but would not bate a whit of their burdens. One passed me bearing on her head a shallow wooden dish of mighty size, inverted, hat-wise. There were tiny children, hardly old enough to walk. I saw a pair of new-born calves, yoked together at the neck. Frail as they were they must bear some household burden; and even sheep and goats had packs and nets of fruit on their backs. A fainting rabble followed in the army’s wake, and the desert way for close on twenty miles was strewn with discarded horse-gear, cooking pots, a chair or two, and miscellaneous litter from the Arab tents.35

It seems probable that the 2nd Brigade had mismanaged its swing to the east, and so rather than cutting off Ain Zara it merely approached it from that direction. This left the south uncovered and allowed the former occupants to escape. This was not unobserved as has already been noted, and why the Italians, and particularly their cavalry, made no attempt to intercept this mass is a mystery. Little resistance would have been encountered, since to cover the retreat, or at least to give warning of Italian intentions, only a small detachment of cavalry under Captain Ismail Hakki had been deployed. They were not called upon to do any fighting, but according to Abbott, who got the story from him later, Hakki observed the Italians from the top of a high dune. From a distance of some 150 metres he had a good view of at least the vans of both brigades in the moonlight, and he saw them deploy outposts whilst the battalions behind them remained massed. There was much shooting by the sentries at shadows and bushes swayed by the breeze, but his conclusion was that the Italians had settled down for the night. Once he had established that there was no danger of any further activity from the Italians, Hakki returned to Ain Zara at around 21:00 hrs and calmly dined. The Italian decision allowed several parties of Ottoman combatants from north of Ain Zara to pass through it during the night without hindrance, and the last contingent from the oasis left at 04:30 on the morning of 5 December with a small caravan of camels. The oasis was occupied by the Italian forces at daybreak without fighting and work on constructing entrenchments immediately began.

The capture of Ain Zara was undoubtedly a useful victory, though not perhaps of quite the stature that the Italian army made of it. Reports based on a communiqué issued from Tripoli on 6 December told their version of the battle:

The fighting lasted from daylight to dusk. When darkness began to fall, 8,000 Turks and Arabs disappeared rapidly to the south-east. A long line of camels was with them, bearing their wounded. The Turks lost several hundred killed, while the Italian casualties are estimated at 100. The headquarters staff of the Italian Army asserts that the battle was a decisive one for the possession of the country, as it has almost entirely cleared the oasis around the town of Tripoli and forced the Turks from the coast and away from their bases of supplies.36

This pronouncement, as with all similar types issued during the conflict, must be treated with some scepticism. Though there are no accurate reports of, and no way of calculating accurately, the number of those who evacuated Ain Zara, it seems highly unlikely that they numbered anything like 8,000. The best estimates, made from the observations of the various foreigners, mainly correspondents, who retreated with the Ottomans reckon the numbers to have been less than 4,000, including non-combatants. Neither did the capture force the enemy ‘away from their bases of supplies’; these, such as they were, were not on the coast, which was already dominated by Italian naval supremacy. The claim about the battle clearing the enemy from the Oasis of Tripoli was however accurate, or mainly so. Although a number of irregulars had declined to obey Nesat’s order to evacuate, they were few, and when the eight battalions of Rainaldi’s strengthened 1st Brigade resumed the offensive they made swift headway. Tagiura was occupied on 13 December without serious opposition.

Frugoni had then, by the use of a military force ill-equipped and poorly trained to deal with the terrain, manoeuvred his enemy out of their position at Ain Zara without serious fighting; the total Italian casualties are reckoned to have been 17 killed and 94 wounded. This can be viewed as tactically skilful, however at the operational level the battle was a failure inasmuch as it did little to diminish the Ottomans capacity to resist. The main factor in this was that, by accident or design (and probably the former), the 2nd Brigade and the cavalry had turned too soon to cut off the enemy and prevent their retreat. Had Ain Zara been encircled from the south then it is at least possible that a large number of Ottoman regular troops might have been captured, which would have severely weakened the ability to resist Italian occupation. Pursuit of the retreating enemy was also rendered difficult, if not impossible, because the traditional main arm of pursuit, the cavalry, were weak (two squadrons at 142 men per squadron).37 Also, and like the infantry and artillery, they were unable to operate properly in such difficult terrain. Indeed, the fact that such a small force of cavalry was attached to the right wing of the brigade suggests that using them in pursuit was not envisaged, and that their task was confined to screening the flank of the advance.

The Ottomans retired initially to Azizia, some 40 kilometres to the south-west, but once the Italians began strongly fortifying Ain Zara they advanced their main position some 20 kilometres to Suani Ben Adem (Senit Beni-Adam). This place was, as McClure noted, close enough to threaten the surroundings of Tripoli, whilst being ‘far enough away to admit of an easy retreat […] if that course should seem politic.’38 That a retreat, easy or otherwise, would not become politic was quickly to become evident.