Chapter 8

The importance of visual design

Abstract

This chapter provides a high-level summary of the various elements of visual design most relevant in data visualizations.

Keywords

visual design

preattentive processing

Gestalt

perception

color

typography

eye candy

“Create your own visual style…let it be unique for yourself and yet identifiable for others.”

—Orson Welles

To set the tone for this chapter, I borrowed a few wise words from Hollywood icon Orson Welles. But, perhaps another quote that adds spice to this rhetoric comes from a more unlikely place: Harry Potter’s Professor Severus Snape, brought to life in film by the incomparable Alan Rickman. Potter-fans may remember many of Snape’s feisty oneliners, however it was upon Harry’s first day of potions class in his first year at Hogwart’s School of Witchcraft and Wizardry that, speaking of potion-making, the Professor enigmatically says to his class, “You are here to learn the subtle science and exact art of potion making.”

The potion master’s words echo the essence of the complex and beautiful science of data visualization. It is both subtle and exact—and it is perhaps even a little bit mysterious. There are many elements that go into designing an effective data visualization, from the appropriate use of color and counting techniques, to the affect of typographies and other visual design building blocks, like lines, contrast, and forms, and many more beyond—not to forget, of course, the also very important (and evolving) data visualization best practices that tell us how to visualize different types of data and which features to emphasize visually. Many of these are “science” because they take advantage of preattentive features of our visual brains or other levies of cognitive horsepower. Others are more exact and depend on the mechanics of design and other affective properties, like cultural biases or contingencies in the way different people perceive colors. In any case, it is fun to imagine a visual analyst standing over a bubbling cauldron, tipping in bits from various vials to brew that perfect blend of all the above.

Our discussions in Part II of this book have thus far focused on data visualization primarily as a mechanism for visual communication—one who taps into generations of cognitive hardwiring custom built to understand, learn, and communicate visually. We have also rummaged into story psychology, and the various nuances of genre, narrative design, and storytelling tactics best suited to tell a meaningful data story. All of these are valuable conversations that guide us in how we can visually and simply articulate the complexity of data to its intended audience and through its intended storytelling media, whether information visualization or otherwise.

The best data visualizations are, somewhat like potions, a carefully curated blend of art and science. And as such, data visualization requires equal attention to be paid to both the visualization method as well as to how the data is visually presented. Visual design and data visualization mechanics are separate yet highly interrelated concepts that work together to visually create meaning from data. Applied in data visualization, these elements can exploit our brain’s cognitive functions to help us better see and understand information. This chapter will tackle the first half of the equation and provide a visual design checklist of core design considerations applicable to successful data visualization.

But first, allow me to serve up a few disclaimers and level set expectations. Many researchers, colorists, and other visual design experts have devoted entire texts (and careers) on studying each of the design elements we will cover in this chapter. Thus, I can offer only a very distilled introduction to the beautiful science of data visualization within the confines of one chapter. Consider this chapter a crash-course on visual design with only a sample set of design issues—or, Visual Design 101. For further study into one of these areas, I recommend you to source more comprehensive texts.

Second, is a more practical concern: this book is printed in black and white. In a chapter devoted to design—wherein our conversations naturally gravitate to things like color—you might see how this can be problematic and a challenge to showcase the true effects of visual elements. Therefore, I am limited by what I can show you versus what I can tell you.

8.1. Data visualization is a beautiful science

Right off the bat, when you think of data visualization, you likely think of the artistic elements first—things like color and shape are often what come to mind before the mechanics of visualization, like which type of chart, graph, or other form of analysis best suited for the type of data and the intended insight. It is actually the most logical approach if you think about it, because we are visual creatures by nature. In fact, the human visual system has—by far—the highest bandwidth of any of our senses. Our visually evolved brains are our best tool for decoding and making sense of information.

It is fitting to say that as people, we love pictures. Whether they are art, captures of memories, or merely illustrations for instructional or other educational purposes, pictures are powerful. As an example, think again about the evolution of photography (as mentioned in chapter: Visual Communication and Literacy). In the late 19th century, photography emerged as an expensive, labor-intensive process, quickly matured into a mass-market (or, self-service) endeavor in the early days of the 20th century, and has since continued to evolve, adapt, and become more and more a part of every day life with its current position of digital daily documentation. It is an image explosion: some research has estimated that we took over one trillion photos in 2015. And, that is just photographs, and does not include other forms of visual communication—like data visualization.

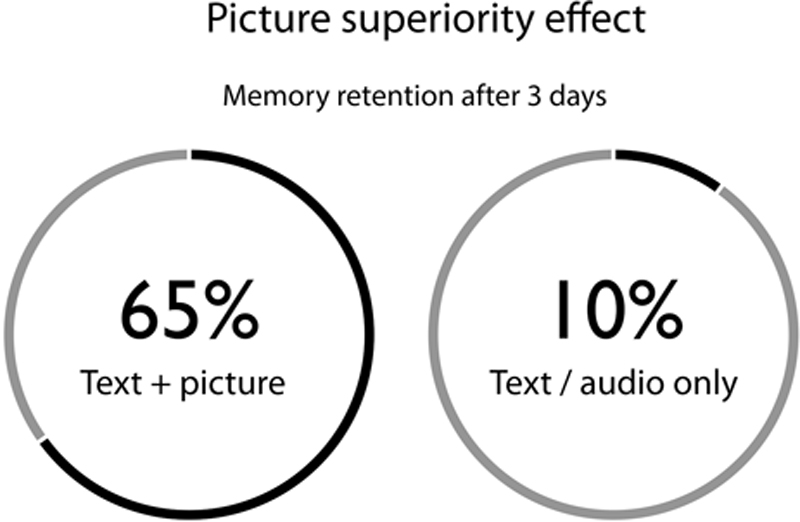

We have already discussed image saliency, drawing on seminal research that quantified our ability to remember and recall upward of 10,000 images at one time, and at an 83% accuracy rate. Even more important, as we have seen established in recent research, is that people remember pictures better than words—and we remember images long after we have forgotten the words that go with them. We can describe this as the “experience” of looking at an image, or as it is more formally known, the Picture Superiority Effect. Simply, this is the notion that concepts that are learned by viewing pictures are more easily and more frequently recalled than those learned purely by textual or other word-form equivalents (which also includes audio words). One prominent way of articulating the particulars of the Picture Superiority Effect comes from developmental molecular biologist John Medina (2014), who succinctly qualified it in the following way: when we read text, in three days we only remember 10% of the information. In contrast, information that is presented visually gets a much heftier earmark in our remembrance. Text combined with a relevant image is more likely to be recalled at 65% in three days. The above visual is both a representation of this concept and a practicable example of it (see Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 The Picture Superiority Effect

This visual depicts memory retention after 3 days. The first circle shows text/audio only at 10% after 3 days, juxtaposed at 65% after 3 days for information learned via text and picture

This visual depicts memory retention after 3 days. The first circle shows text/audio only at 10% after 3 days, juxtaposed at 65% after 3 days for information learned via text and picture

Without getting too caught up in the details, we can simply say that it is a cognitive truth: our visual system is enormously influential in our brains. The best data visualizations are designed to properly take advantage of “preattentive features”—a limited set of visual properties that are detected very rapidly (typically within 200–250 ms) and accurately by our visual system, and are not constrained by the display size. With that mindset in place, let us explore few of those special ingredients of design that contribute to the visual curation of data.

8.2. Key cognitive elements in visualization

Any work of art relies on core visual design principles and elements. When we say, “design principles” what we are really saying is shorthand for the list of guidelines that help improve viewers’ comprehension of visually encoded information. Though there is a long list of visual design principles within the scope of the larger conversation of designing data visualization, we will limit this conversation to what could be considered the three most important cognitive elements of visual analysis. These are pattern recognition, color use, and counting. While distinct concepts on their own, they are interconnected and can be integrated to visually create meaning from data. Applied as a unit in data visualization, these elements can exploit our brain’s intrinsic horsepower to help us better see and understand data. With self-service and user-oriented data visualization tools, we can leverage our natural hardwiring to layer visual intuition on top of cognitive understanding to interact with, learn from, and reach new insights from our data.

Data visualization should work to establish visual dialog. This two-way dialog leverages our cognitive visual hardwiring–and the power of perception—to have a “conversation” with the data. Through this dialog, we glean new information in salient, memorable, and lasting ways. And, this conversation is incremental: it builds on what came before to construct layers of learning and insight upon itself. It is also expressive, adding meaning, emotion, and understanding to transform information form mundane data to a creative palette by which to present it. The data visualization is the tangible byproduct of when art and science come together to facilitate a visual discussion of data. And, this is how data visualizations can be storytelling mechanisms to communicate quantitative visual narratives, told through sequential facts and data points.

Not to beat a dead horse, but again, there is wisdom in the old adage that says, “The more you know, the more you see.” Understanding and awareness of the elements discussed above are intended to help us to craft data visualizations that balance art and science while keeping a wary eye on the power of pictures and visualization constraints. On its own, we should never mistake beautiful data visualization for effective data visualization. In fact, many memorable, beautiful data visualizations are those now infamous for being flawed in terms of data analysis. Thus, there exists the need for guidance in analyzing imagery and making sure that visual dialog is a worthwhile, accurate conversation between the visual and its audience.

8.2.1. Patterns and organization

The way we perceive patterns is one of our most interesting cognitive functions. Patterns—the repetition of shapes, forms, or textures—are a way of presenting information help our brains discriminate what is important from what is not. There are patterns around us every day that we may not even recognize—for example, the way television show credits list actors in a series (generally the top star first and the second last, making the first and final data points in the pattern the most significant). Patterns are how our brains save time decoding visual information: by grouping similar objects and separating them. The Gestalt principles of design emphasize simplicity in shape, color, and proximity and look for continuation, closure, and figure-ground principles. In fact, the German word gestalt literally translates in English to “shape form,” or pattern. Gestalt psychology assumes that visual perception is a holistic process (a la “the whole is worth more than the sum of its parts”) and that humans tend to perceive simple geometric forms.

When we look at any data visualization, one of the first things that the brain does is look for patterns. We discriminate background from foreground to establish visual boundaries. Then we look to see what data points are connected and how (otherwise known as perceptual organization)—whether it is through categorical cues like dots, lines, or clusters, or through other ordinal visual cues like color, shapes, and lines.

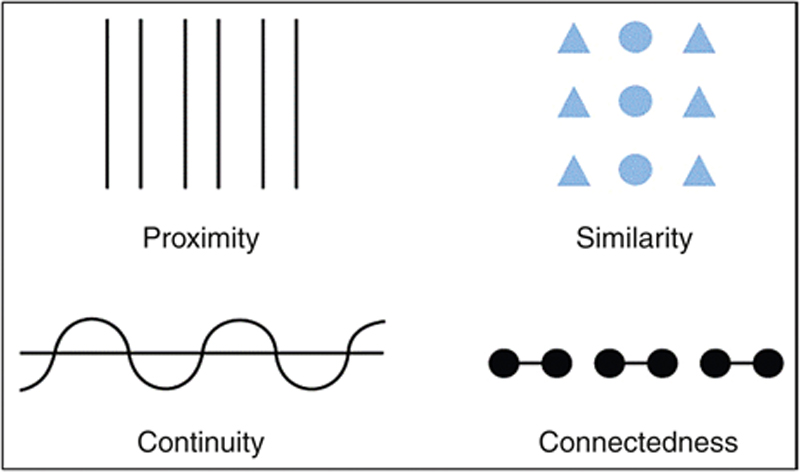

Typically, there are four core ways in which we apply pattern recognition to data visualization (see Figure 8.2). Though only a subset of the Gestalt Laws, these are:

Proximity: Objects that are grouped together or located close to each other tend to be perceived as natural groups that share an underlying logic. Clustered bar graphs and scatter plots utilize this principle.

Figure 8.2 Four Core Ways We Apply Pattern Recognition to Data Visualization

Similarity: This principle extends proximity to include items also that are identical (or close). This gives the brain two different levels of grouping: by the shared, common nature of objects, as well as how close they are. Geospatial and other types of location graphics utilize this principle.

Continuity: It is easier to perceive the shape of an object as part of a whole when it is visualized as smooth and rounded – in curves –, rather than angular and sharp. Arc diagrams, treemaps, and other radial layouts use this principle.

Closure: Viewers are better able to identify groups through the establishment of crisp, clear boundaries that help isolate items and minimize the opportunity for error (even if items are of the same size, shape, or color). This effect would be applied, for example, in a clustered bar chart to add additional organization to the pattern by alternating shading the area behind groups of bars to establish boundaries.

Patterns help to establish clear visual organization, composition, and layout. Once we can see patterns in information, we can next coat visual intuition on top of cognitive understanding to come to new conclusions. This is where color and counting come in.

8.2.2. Color use

Colors and shapes naturally play a large part in patterns. Color (or the lack thereof) differentiates and defines lines, shapes, forms, and space.

However, the use of color in design is very subjective, and color theory is a science on its own. Colorists study how colors affect different people, individually or in a group, and how these affects can change across genders, cultures, those with color blindness, and so on. There are also many color nuances, including overuse, misuse, simultaneous and successive color contrast, distinctions between how to use different color hues versus levels of saturations, and so on. At the moment, let us focus simply on when and how to use color in visualization to achieve unity. We will discuss the basics of color theory and a few select color contingencies a bit later in this chapter.

In The Functional Art, Cairo (2013) writes, “The best way to disorient your readers is to fill your graphic with objects colored in pure accent tones.” This is because pure colors—those vibrant “hues of summer” that have no white, black, or gray to distort their vibrancy—are uncommon in nature, so they should be limited to highlight important elements of graphics. Subdued hues—like gray, light blue, and green—are the best candidates for everything else. Most colorists recommend limiting the number of colors (and fonts and other typography) to no more than two or three to create a sense of unity in a visual composition. Unity is created when patterns, colors, and shapes are in balance.

When thinking about color use in your data visualization, first focus on how well (or poorly) you are applying your color efforts as visual targets. Be especially cognizant of:

Color and Perceptual Pop-Out or the use of color as a visual beacon or target to preattentively detect items of importance within visualization. The shape, size, or color of the item here is less important than its ability to “pop-out” of a display. Color differentiates and defines lines, shapes, forms, and space. (This theory has come under some criticism, however it nonetheless has been very influential for data visualization and visual analytics.)

Conjunction Target is the inefficient combination of color and shape. Rather than giving target feature one visual property, conjunction targets mix color and shape. That distracts and causes visual interference, making visual analysis and other cognitive processes slower and more difficult. Thus, it is prudent to maximize cues like perceptual pop-out, while not inadvertently interrupting the preattentive process with conjunction targets.

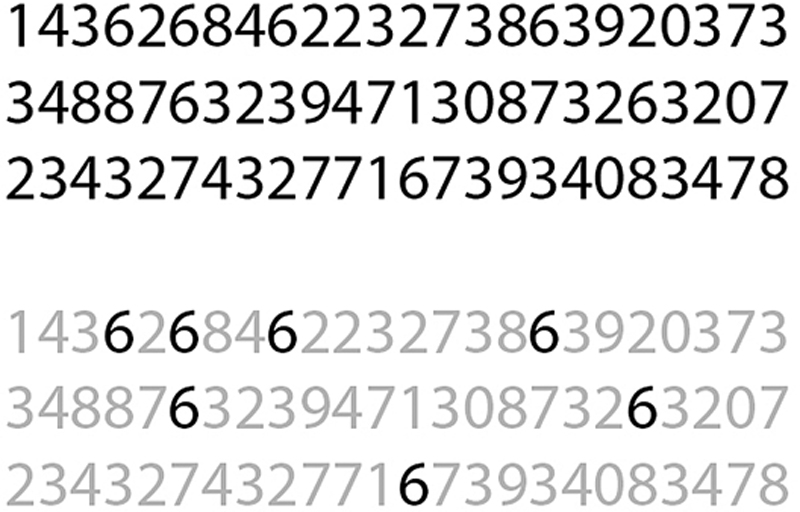

As illustration, Figure 8.3 is inspired by a picture made by visualization guru Stephen Few. It is much harder to see the number 6 in sequences without the benefit of shading. Likewise, we can take advantage of perceptual pop-out by adding an additional color element into the picture. It is much more fun to add some wow factor to this example and throw in some red or other primary color to bring some zing, but in the humble black and white example we can show this—very simply–by using gray scale to show the number six in black against a background of gray. This example shows how elements of pattern recognition, color, and shape can be used together while avoiding the clutter of conjunction targets.

Figure 8.3 Perceptual Pop-Out

Inspired by Stephen Few, this visual shows the immediate impact of perceptual pop-out

Inspired by Stephen Few, this visual shows the immediate impact of perceptual pop-out

8.2.3. Counting and numerosity

Color and counting work in tandem, as do counting and patterns. Relatively new research shows that the brain has an ordered mapping, or topographical map, for number sense, similar to what we have for visual sense and other preattentive features.

There are two relevant counting conversations within the scope of data visualization. First is how data visualizations try to reduce counting by clustering or similar approaches designed to replace similar data objects with an alternative, smaller data representation. Histograms take this approach. Visual spacing on linear scales versus logarithmic scales is another example.

Second is numerosity—an almost instantaneous numerical intuition pattern that allows us to “see” an amount (number) without actually counting it. This varies among individuals (people with extreme numerosity abilities are known as “savants”). Numerosity itself is not an indicator of mathematical ability. In fact, it is an important note to understand that numerosity only applies to numerical count, and is different from mathematical ability or symbolism. For most of us, numerosity gives us the ability to visually “count” somewhere between one and ten items. We can further enhance numerosity with visual elements like color. As an exercise, glance quickly again at Figure 8.3. How many black sixes do you see? If you “see” 7, you are correct. Most types of data visualization will include a numerosity effect, however those that take advantage of data reduction processes will be most beneficial for numerosity. Consider scatter plots, histograms, and other clustering visualizations.

Neuroscientists at Utrecht University in the Netherlands have recently investigated how the human brain maps numbers. Previous studies in monkeys have shown that certain neurons in the parietal cortex, (which is located at the back of the brain, beneath the crown of hair) activate when these animals viewed a specific number of items. Could the human brain also produce such a recognizable, topographical map of numerical quantity in the brain study? Such a map has been long suspected to exist, but yet to be discovered. The answer, as the study details—which were outlined in the September 2013 issue of the journal Science—is yes.

The science is overwhelming complex, but here is a digestible recap: researchers placed participants under an MRI and showed them dots of various groups over time (one dot, three dots, five dots, two dots, etc.). They used an advanced, high-field MRI—known as fMRI, which allowed them to see fine-scale details of brain activity, and gather the data needed to analyze neural responses. The brain acted like an abacus (in laymen’s terms: a device for making calculations—or, that cool toy with the beads on wires that many of us remember playing with back in our elementary school days) (Lewis, 2013).

To include an image here without color would never do an illustration justice, but imagine a heat map—or some beautiful storm system on your nightly weather forecast—blanketed over part of your brain, and you will imagine something very similar to the data visualization provided by the researchers. Thus, the topographical counting map of legend. As it “saw” dots, the posterior parietal cortex responded and organized them by their count: small numbers in one area, larger areas in another. These findings are in line with previous research that has shown that number sense becomes less precise as quantity of items increases (a finding, which has been the catalyst behind things like reduction techniques that are so prevalent in many data visualization taxonomies). They also suggest that our higher cognitive functions might rely on the same organization principles (eg, face recognition) as do our other sensory systems.

8.3. Color 101

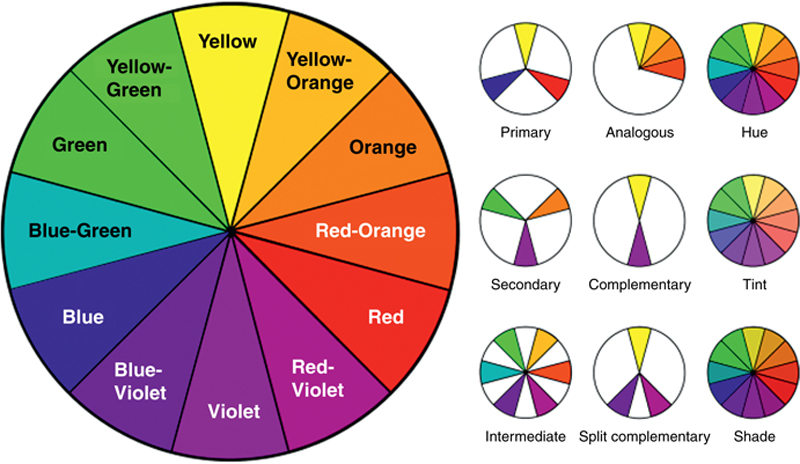

With the earlier discussions on color already top-of-mind, let us dig a bit deeper. We talked about the use of color in visuals already, so for this next section let us tackle a few specific applied color contingencies that affect data visualization design. This begins with a cursory overview of very basic color theory, which most of us are at least superficially aware of. We are taught primary, secondary, and tertiary colors in elementary school, and how together these colors make up the basic color wheel.

With the color wheel (see Figure 8.4), we can make purposeful choices of color combinations depending on what we are trying to accomplish—like contrast, blending, or other effects. In our basic color education, we are also taught the purpose of complementary colors—those opposite each other on the color wheel—and how they provide the most contrast, or noticeable level of difference between two colors. More contrast means more visibility, which is why you often see highly-contrast colors used together (for example, these black words printed on a white page background). The opposite of the complementary colors are the analogous colors. Unlike complementary colors, analogous colors are those that neighbor each other on the color wheel and therefore have very little contrast and, instead, are nice harmonious blends (for example, orange and red). Finally, our basic color education also teaches us that colors often come with feelings, moods, and other cultural associations—like red for danger or warning; green for go or good; or even purple for royalty—that we infuse into the meaning of the color. This is related but separate from the warm versus cool color schema that segregate “cool” colors (those that are general considered calm and professional, like blues, greens, and purples) from “warm” colors (those that reflect passion, happiness, and energy, like reds, oranges, and yellows).

Figure 8.4 A Gray Scale Modified Traditional Color Wheel

Of course, there are many more facets to studying color, but for the basis of our conversation, a simple nod to the color wheel and a few of its most common facets will suffice. Now, let us move on to color contingencies.

8.3.1. Color contingencies

Beyond the basics of color theory, there are a few pockets of color contingencies we should pay special attention to. These are a sample set of color-based issues most commonly experienced when designing for data visualization, and thus worthwhile to briefly explore. There is a lot of truth to the saying that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

8.3.1.1. Color blindness

For the most part, we all share a common color vision sensory experience. However, “most” does not equal all, and there is a segment of the population—as many as 8% of men and 0.5% of women (according to the National Eye Institute (2015))—that suffer from some kind of color vision deficiency (or, CVD). Color blindness is typically the result of genetics, though in some cases it can result from physical or chemical changes in the eye, like vision deterioration, medications, or other vision damagers. Basically, this means that these individuals perceive colors differently from what most of us see, usually without knowing that it is different. There are three main types of color blindness: red–green (the most common), blue–green, or the complete absence of color vision—or, total color blindness, which is extremely rare. While our brains have about six million color cones (the term for those photoreceptors in the retina that perceive color), blue color cones are by far the fewest (Mahler, 2015). Thus, blue is the trickiest color for our brains. If you do not have as many blue cones, you may see the color as white, whereas if you have plenty, you may see “more” blue. This could have been one of the reasons behind one of the Internet’s most recent color controversies on a certain mother of the bride’s dress (see Box 8.1).

This is not the time or place to go into a lengthy discussion on the intricacies of color blindness or the science behind it. For now, it is enough to take away the fact that some people do perceive colors differently, and this has serious design implications on data visualization. Each flavor of CVD lends its own set of challenges when trying for consistent visual experiences. This affects everything from being able to read color-coded information on bar or pie charts or visually decode more complex visualizations like heat maps or tree maps. Color blindness can also be material specific—some people may have a harder time distinguishing color on artificial materials than on natural materials—thus a difference in digital displays versus on paper. So, obviously we want to take color blindness into account when crafting a data visualization to ensure that everyone is seeing the same data story unfold as everyone else.

There are a few tricks of the trade for designing to mitigate the affects of color blindness. Consider these:

• Avoid situations that could be tricky for color blindness factors. For example, rather than relying on color alone, make use of shapes (or even symbols) to supplement color-schemes without worrying too much on color perceptions.

• Be wary of similar-intensity colors and how they might look (or not look) in close proximity. For example, colors used in choropleth, tree, or heat maps. For those times when those types of designs are the best way to communicate information, consider using labels or other visual cues to help separate areas and further distinguish colored areas.

• Fight back against color blindness challenges and know which color combinations that can be used to usurp color blindness issues.

• When in doubt, go with gray. Even those with total color blindness can typically distinguish between varied shades of black and white.

Some of these may seem abstract now, but keep these tips in mind in the next section on visual design building blocks, when we look at things like shapes and texture more closely.

8.3.1.2. Color culture

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but perhaps it is just as accurate to say that color is also in the eye of the beholder—and not just due to genetic visual differences. In addition to vision abnormalities that cause people to perceive colors differently, people of different cultures or even genders may also (and often do) “see” colors differently.

8.3.1.2.1. Color symbolism

The more obvious of the two may be color symbolism. This term, based on anthropology, refers to how color is used, symbolically, in various cultures. There is great diversity in how different cultures use colors, in addition to how color is used within the same culture in different time periods or in association with holidays or other iconic associations. Let us have an example to illustrate how color symbolism is viewed on a larger cultural scale. Imagine this scenario: you are at a wedding, and the bride steps out in her beautiful wedding gown. What color is her dress? Most of you would probably say white (or ivory). In western culture, the color white (which is technically the presence of all colors in the visible spectrum) is typically associated with things like brides, or angels, or peace, or purity and cleanliness. However, in China, white would not be an appropriate color for a wedding as it is culturally a color of mourning. Likewise, in India, if a married woman wears unrelieved white, she is seen to be inviting widowhood and unhappiness—not the expected attitude of a bride! Those of Celtic heritage might argue that green is the most appropriate wedding color, as in Celtic mythology the Green Man was the God of Fertility. In fact, in the 1434 Renaissance painting “Giovanni Arnolfini and His Bride” we see the bride wearing a green gown—and slouching in an imitation of pregnancy to indicate her willingness to bear children.

As we continue to become a more and more globally connected world, it is important to be aware of the cultural perceptions of color. For recommended reading, check out Color and Meaning: Art, Science, and Symbolism by John Gage or Secret Languages of Color: Science, Nature, History, Culture, Beauty of Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, & Violet by Joann and Arielle Eckstut, both of which are quite fascinating. Or, if you are looking for a quicker takeaway, think on this: the red circle on a scorecard that you think means a negative (ie, a warning or caution sign) if you are in America might actually be something much more positive—like good fortune if you are in China—or rouse a more sorrowful emotion, such as mourning, if you are from South Africa. How might that one simple indicator change on a globally-accessed dashboard environment?

8.3.1.2.2. His and hers colors

It should be no surprise that if people from different cultures “see” colors differently, then so would people of different genders. If men are from Mars and women from Venus, then seeing colors different would almost certainly make sense. But, whether it is politeness or a sense of decorum, men and women do apparently perceive color differently.

A 2010 color survey hosted by XKCD.com generated 222,500 user sessions to name over five million colors based on RGB color samples (see the full color survey results at http://blog.xkcd.com/2010/05/03/color-survey-results/). The results were hilariously honest, and provided some interesting data on to how men and women look at colors differently. For example, a brownish-yellow color that men would describe as “vomit” is one that women might more diplomatically name “mustard” (Swanson, 2015). Analyzing the survey results, there was a noticeable trend that women also tended to be very generous (and somewhat overly-descriptive) in naming different color shades, with a disproportionally popular naming convention of things like “dusty” teal or “dusky” rose. (Another interesting find in the study is that spelling was a consistent issue across everyone—men, women, the color blind, and so on—which is probably a larger issue on vocabulary issues.)

Of course, there were some issues with the survey and it was by no means academic—though it was certainly a fun thought experiment. For one, being an informal distribution there is almost certainly some noise and bias built in. The researchers did use filters to drop out spammers and other outliers or scripts that junked up the data (like one spammer who used a script to name 2400 colors with the same racial slur). Secondly, since the survey was conducted online, it is right to assume that the monitor display of color would vary, especially since RGB is not an absolute color space. However, the difference in how colors appear across various monitors is in itself quite important when we think in terms of data visualizations, which are almost always presented digitally.

In early 2015, Stephen Von Worley of the data visualization blog Data Pointed visualized 2000 of the most commonly used color names mapped by gender preference. It is a stunning, interactive data visualization that could never done justice in black and white print, but you can view it online at www.datapointed.net. Ultimately, the takeaway here is simply that color comes with perception, and we must be aware of the opportunities and limitations of these as we create visualizations meant to resonate and engage.

8.4. Visual design building blocks

When you first look at a data visualization, you may not realize just how much careful thought and effort went into crafting it. Data visualizations are multifaceted, not just because of their ability to represent multiple types of data and layer it in a meaningful visual way, but because to craft the visualization itself requires attention to every detail—from its carefully curated color pallet, to the methods in which the important pieces of information are connected into patterns, to the layout and chosen typefaces used throughout the graphic.

In the previous section, we focused on key preattentive features—color, patterns, and counting—that form the basis of a visual dialog with data. In this section, we will take a deeper look into how to curate visual meaning in the data through more specific elements. These—lines, textures, shapes, and typography—are some of the visual cues that influence how your eyes move around a visual to separate areas of importance from nonimportance. More important, they are the visual cues that guide us to create meaning and organize visual information in the way that is necessary for visual discovery.

8.4.1. Lines

The most basic building block of visual analysis, lines facilitate several purposes in data visualization. They are used to create complex shapes (discussed in the following section), to lead your way visually through (or to) different areas of a visualization, or as a way to layer texture upon a visual surface.

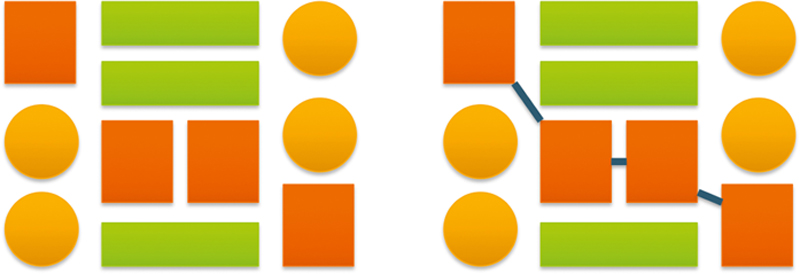

Lines are especially potent tools to reinforce patterns. This is because they offer powerful cues for the brain to use to perceive whether objects are created. Consider a diverse group of different colored shapes. With its preattentive capabilities, the brain will automatically group them by shape and color. Adding a line to connect certain shapes will add more connectedness, and produce a more powerful pattern (see Figure 8.5). As another example, consider a graph where distance, shape, and other elements are laid along one axis. The brain will perceive them as a single set of data, but lines—particularly curved lines, as opposed to sharp-angled lines—will provide closure and logically group sets of data into a recognizable pattern (this is the pattern principle of continuity).

Figure 8.5 This Figure Shows the Added Patterning Influence of a Line as a Visual Vue

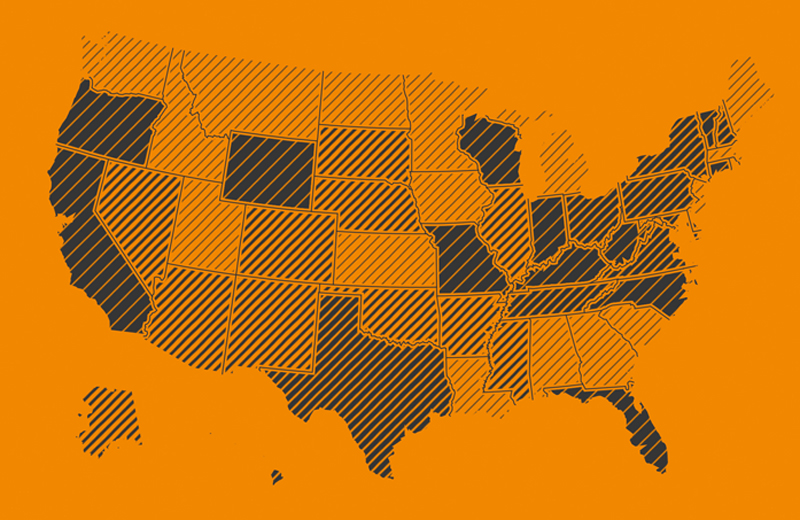

Lines can be used as labels, direction cues, or they can also be used as a way to create texture in data visualization. Texture is one of the more subtle (and easy to misemploy) design elements, but worth a mention due to its relation to line (and our previous discussions on color).

Texture is defined as the surface characteristics (or, the feel) of a material that can be experienced through the sense of touch (or the illusion of touch). It can be used to accent an area so that it becomes more dominant than another, or for the selective perception of different categories. Colors, shapes, and textures can be combined to have further levels of selection (see Figure 8.6). Finally, textures of increasing size can represent an order relation. Because it is usually accompanied with real adjectives like rough, smooth, or hard, texture may seem intrinsically three-dimensional (real). It can also be two-dimensional.

Figure 8.6 Even in Gray Scale, This Image, Created by Designer Riccardo Scalco, Shows How Colors, Shapes, and Lines can be Combined Together to Create Texture and Areas of Selection

In data visualization, lines are one of the best ways to represent texture. For example, when used in tandem with color, lines can create texture through what is called “color weaving” to produce a tapestry of woven colors to simultaneously represent information about multiple colocated color encoded distributions. As an example, color weaving is similar to the texturing algorithms and techniques used to visualize multilayer in weather maps and other climatology visualizations. That said, texture can be a tricky and easily misused element of data visualization, and thus should be employed sparsely and with careful discretion.

8.4.2. Shapes

In his late 19th-century article “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” Louis Sullivan (2012) made a statement that has forever impacted how we approach the premise of shapes and forms. He said:

“All things in nature have a shape, that is to say, a form, an outward semblance, that tells us what they are that distinguishes themselves from another…It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human and al things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function.”

Over the years, this “form follows function” refrain has been taken both as gospel verbatim as well completely misinterpreted (it has also been described as “coarse essentialism” by data visualization design gurus like Albert Cairo). Today, in visual design, it is a powerful mantra primarily applied to the relationship between the forms (of design elements, ie, shapes and lines) and the informational function it is intended to serve.

As forms, shapes are one of the ways that our brains create patterns. This is a time saving technique: we will immediately group similar objects and separate them from those that look different. So, shapes and forms should be driven by the goals of what the visual is communicating about the data.

Shapes are formed with lines that are combined to form squares, triangles, circles, and so on. They can be organic—irregular shapes found in nature (circles, etc.)—or geometric—shapes with strong lines and angles (like those used in mathematics). Likewise, shapes can be two-dimensional (2D) or three-dimensional (3D). These 3D shapes expand typical 2D shapes to include length, width, and depth—they are things like balls, cylinders, boxes, and pyramids. In data visualizations like pictograms, infographics forms and shapes take on an entire new catalog of options through the issue of icons and other symbolic elements as extensions of traditional shapes (consider using the shapes of people in lieu of dots or other shape). Some visualizations, like D3.js, made liberal use of nontraditional visual shapes. Further, like so many other elements of design, color has a hand in shape selection, too. This is particularly relevant in two ways: (1) Make sure you are using color priority in choosing a shape (if you want to use circles to emphasize areas of opportunity for sales agents on a map use green circles instead of, say red or orange), and (2) Be aware of color contrast and luminance among shapes. The higher the luminance contrast, the easier is it to see the edge between one shape and other. If the contrast is too low, it can be difficult to distinguish between similar shapes—or to even distinguish them at all.

Like many visual cues, there is often no “one right way” of encoding visualization properly through the use of shapes and forms. Many times it becomes less a question of “correct” and more a consideration for what is easier for the view. As an example, both a scatterplot and a bar chart can be used to represent absolute variables. But, to represent correlations using absolute variables, one scatterplot can essentially tell the same story as a pair of bar charts. Do not limit your thinking on shapes to just 2D or 3D. Some data visualizations—for example, bubble charts—can invoke another data dimension from bubble size when on an x-y axis. Here, color can add a 4th dimension of data to represent buckets or thresholds. Animation can add a 5th dimension. Remember: humans can visually process three to five dimensions of data.

8.4.3. Typography

There is a large vocabulary when it comes to typography, and often times those unfamiliar with the nuances of each term will make use of them interchangeably. While they are compounding and interrelated terms, they do carry different meanings and should not be used synonymously. Thus, for the purposes of our discussion let us take a moment to define clearly three of the most commonly confused of these terms: typography, typeface, and font. These definitions will serve us well going forward.

Typography itself is the study of the design of typefaces, and how they are laid out to best achieve the desired visual effect while conveying meaning to the reader

Typeface is the design of the type itself (ie, Helvetica or Arial or Times New Roman)

Font is a specification for a typeface (ie, 12pt bold Helvetica)

Generally speaking, when we think of typography within the context of a data visualization, we think in terms of two choices of typeface categories: serif versus sans serif. While the origin of the word “serif” is unknown, a common definition for it has come to be “feet”—small lines that tail from the edges of letters and symbols, and are separated into distinct units for a typewriter or typesetter. The concept of serifs as feet actually has a cognitive origin: feet were created to allow for ease of reading by providing continuity along letters, words, and lines/sentences in long bodies of text. Thus, serif typefaces—like Times New Roman or Baskerville, are those with “feet.” Building on the previous, the word “sans” comes from the French “without.” Thus, sans serif typefaces are those “without” feet. Serif fonts are usually considered to be more traditional, formal typefaces, while sans serif typefaces tend to have a more contemporary, modern feel. There are no absolutes of when—or when not—to use a serif versus a sans serif typeface, though a rule of thumb is that serif is better for print while sans serif is better for web (see Box 8.2).

In fact, in his book Data Points: Visualization That Means Something, Nathan Yau (2013) pointedly noted that while there has been much discourse on the best typeface, there has yet to be any true consensus. This goes to emphasize further that typeface selection is highly variable and depends much on personal preference. That said there are couple of important points to keep in mind when making a typeface or font selection. First, typography, like another other visual element, is no stranger to bias. There are some typefaces—for example, Comic Sans—that have been reduced to a sort-of comic strip application and are not taken seriously. Others—like Baskerville and Palatino—conjure up nostalgia imagery due to their historical use in vintage graphics. New fonts are being created while others are being improved specifically for readability on smaller devices (like phones and/or tablets) where real estate is reduced and a higher premium on typeface clarity is required. Some typefaces have been custom-created for use in advertising—like those fonts used in Star Wars or Back to the Future, for example, and are pigeonholed into their use in genre-related opportunities (which is not necessarily a bad thing, but one to be aware of). Many typefaces are also said to have personality. Like Comic Sans, others may come with a more light-hearted or conservative personality. Matching type personality with the tone of the message in the visualization is certainly not an exact science. A good technique to see if you are choosing appropriate fonts is to use a font that seems completely opposite of what you are trying to convey. Seeing how “wrong” a typeface can look will help you make a more appropriate selection. And, it is always worthwhile to sanity check a typeface and font across a few different types of devices to double check readability and compatibility.

(Interesting tidbit on type: If you have ever created a text document from a predesigned template, you are probably familiar with the phrase “Lorem Ipsum.” Since the 1500s, the printing industry has used this text to demonstrate what a font will look like without having the reader become distracted by the meaning of the text itself. Although the term resembles ancient Latin, it is not actually intended to have meaning.)

The most pointed advice one can be given on typography is this: use typeface shrewdly and fonts with a purpose. It is easy to dismiss the importance of these selections, possibly because we are so conditioned to read text that we have become accustomed to focusing on the content of the words and not what they look like visually. However, the visual appearance of words can (and does) have just as much effect on how a document is received as the content itself. Fonts can create mood and atmosphere; they can give visual clues about the order a document should be read in and which parts are more important than others. Fonts can even be used to control how long it takes someone to read a document. Like colors, typefaces are typically chosen in corporate style guides and other branding design decisions. Hopefully now you better understand why typography is as important in data visualization as any other design element (not to mention the fun that can be had with word clouds as a visualization itself!).

For a few tips on type, apply the following guidelines:

Like colors and shades, limit type choices in graphics to one or two—perhaps a solid, thick one for headlines, and a smaller more readable one for copy

Remember visual hierarchy—headers should be larger and stand out, whereas tick labels or other content copy should be smaller and demand less attention (sans serif fonts work well for body copy because they are more easily readable in confined spaces)

Make sure the typeface and font chosen for the visualization work together to clearly convey the message of the data as well as the “feel” of the message (a data visualization on mortality rates in impoverished countries would look mighty silly (or even offensive) if delivered in Comic Sans)

8.5. Visualization constraints

You might have noticed a theme in many of these brief discussions on visual cues. They all seem to tie back to one or more preattentive features. It is easy to see how visual cues like line, textures, shapes, and typography are elements that build upon cognitive preattentive features that make our brains so important in visual analysis. Hence, these are only the building blocks of visual discovery, intended by design to be layered upon each other and used in mix-and-match fashion to make the most of our visual capacity for data visualization.

However, one important caveat to remember is that there is such a thing as “too much” design. The point of visual design is to communicate a key message clearly and effectively: the best data visualizations are those where nothing stands between the visual’s message and its audience. When thinking in terms of design, reflect on the minimalistic design mantra “less is more.” Most visualization purists advocate for minimalistic graphics stripped of gratuitous elements with concentration on the data itself. However, used correctly, visual cues can bring the data to life and give more context, meaning, and resonance to information. Data visualizations should be simple, balanced, and focused, and they should use visual enhancements (like hue, saturation, size, and color) judiciously—and for emphasis rather than explanation. Every graphic is shaped by a triangle of constraints: the tools and processes that make it, the materials from which it is made, and the use to which it is to be put.

This idea of design constraints as a triangle of forces comes from historian Jacob Bronowski (1979) and his discussions on context and visualization. In his essay on aesthetics and industrial design entitled “The Shape of Things” (which was first printed in The Observer in 1952 and later reprinted in the 1979 collection of essays, The Visionary Eye) Bronowski wrote: “The object to be made is held in a triangle of forces. One of these is given by the tools and the processes which go into make it. The second is given by the materials from which it is to be made. And the third is given by the use to which the thing is to be put. If the designer has any freedom, it is within this triangle of forces or constraints.” We can thus visualize the triangle in the following way (see Figure 8.8).

Figure 8.8 Bronowski’s “Triangle of Forces” of Design Constraints

Remember, this triangle is not a fixed triangle—each of its axes can move and, consequently, adjust the others along with it. But, because they do not move in isolation, every move of one axis puts strain on the other two. Therefore, it is important to not only recognize the parameters of the triangle of forces, but to strive for balance within it.

8.5.1. The eye (candy) exam

The downside to being able to create visually so quickly and efficiently is that our brains can betray us and leave us with a wrong idea—visual bias. In the context of data visualization, these types of visuals are intended to communicate the correct information and insight clearly and effectively. Thus, we should pay close attention to recognizing the key cognitive elements in visualization, and how these should be used together to craft a meaningful representation of data in a visual way that avoids, or at least mitigates, bias. While we will explore best practices in data visualization in a later chapter, it is worthwhile to apply conversations in this chapter, albeit briefly, within the context of a triangle of forces for data visualization. The worst thing we can do is to spend a ton of time designing something that ends up in the realm of “too much” and distorts, over-embellishes, or otherwise confuses the visual story we are trying to tell by heaping on pretty colors or icons or flashy lines and symbols. Art and science, data visualizations require balance between information and design to be most useful.

To gage the effectiveness of any data visualization, we can ask the three following questions:

Is it visually approachable? First and foremost, make sure the visualization is straightforward and easy to understand by its intended audience. Then, capitalize on the fact that people perceive more aesthetic design as easier to use by including design elements—color, shapes, etc.—to make it visually appealing. This is visual design, or the practice of removing and simplifying things until nothing stands between the message and the audience. In visualization, the best design is the one you do not see.

Does it tell a story? At its core, a visualization packages data to tell a story. Therefore, they require a compelling narrative to transform data into knowledge. Make sure your visualization has a story to tell—a story: one. Too often people want to present all the data in a single visualization that can answer many questions—tell many stories—but effective visualizations are closer to a one-visualization-to-one-story ratio. Focus on one data visualization per story; there is no need for a mother all visualizations.

Is it actionable (or, to use a design concept: does it have affordance)? In other words, does the visualization provide guidance through visual clues for how it should be used? Visualizations should leverage visual clues—or establish a visual hierarchy—to direct the audience’s attention. This is the “happy or uncomfortable” test: before you even know what the numbers say, the design of the visualization should make you feel something—it should compel you to worry or to celebrate.

A well-designed, meaningful, noneye candy data visualization that leverages colors, shapes, and design can not only display, but can influence the way we receive insights into data—which is something we all can benefit from. And that is a tasty win–win for everyone (Box 8.3).

The use of these principles to guide your design and representation of data will improve the efficacy of your visualization, ultimately creating understanding of the data story you are presenting.

It is easy to see how quickly a “scientific” view blurs into a design—or artistic—one. Regardless, whether we approach data visualization first from a scientific perspective or a design perspective, we are ultimately working to ensure that it relies on core visual and cognitive design principles intended to direct viewers’ comprehension of visually encoded information.

This is where the value proposition of data visualization as a tool to communicate complex information really comes into play. Being able to truly see and understand that data requires more than simply drawing a collection of graphs, charts, and dashboards. It is not simply being able to represent the data, but doing so in a way that conveys a message. Data visualization is a creative process, and we can learn how to enrich it by leveraging years of research on how to design for cognition and perception. First, think of successful data visualization from a visual science perspective to ensure you are capitalizing on the right preattentive features to capitalize on the processing horsepower of the brain. Then, consider the careful balance of the art of visual design and curation alongside the observations and insights of data science. The most meaningful data visualizations will be the ones that express unity and correctly present complex information in a way that is visually meaningful, memorable, and actionable.

Beyond the visual design elements that go into making a meaningful data visualization are those best practices that tell us which types of visualizations are best for which type(s) of data, which visual features to highlight, and when it is appropriate to use traditional visualizations versus when customize for a better representation or deeper insight. Remember, a graphic can be functional and aesthetic without correctly using crafted color pallets and other curated elements of visual design. Likewise, it can be beautiful without meaning, or can be meaningful without necessarily being beautiful. As I asserted at the onset of this chapter, it truly is subtle science and exact art.

The key is to avoid overemphasis on trendy chart types that do not add insight beyond what a basic chart would provide—instead, focus on keeping it simple and optimized. Data visualization itself—similar to visual design—depends on both simplicity and focus with the goal of shortening the path to insight as much as possible. This is how data visualizations can achieve unity—when principles of analysis are in sync with those principles of design.

In the next chapter, we will stitch together this discussion of design consideration into the application of information visualization and thus move into more technical discussions on data visualization best practices and graphicacy techniques.