Chapter 10

Architecting for discovery

Abstract

Business-driven data discovery is becoming fundamental for organizations to explore, iterate, and extract meaningful insights into data. With advanced data visualization tools and technologies, and an emerging visual imperative, this process is becoming increasingly visual. This chapter discusses key components of discovery architectures and how to enable visual data discovery across the organization.

Keywords

data discovery

architecture

cloud

hybrid cloud

governance

analytics

“Simplicity, is the ultimate sophistication.”

—Henry David Thoreau

Today’s most disruptive and innovative companies are transforming into data-driven companies, leveraging vast amounts (and new forms) of data into processes that span from research and development to sales and marketing and beyond. In many industries the data is explosive: already the rate of data generation in the life sciences has reportedly exceeded that of even the predictions made by Moore’s Law itself, which predicts the steady continuance of technology capacity to double every two years (Higdon et al., 2013). With every piece of detailed raw data now able to be affordably stored, managed, and accessed, technologies that analyze, share, and visualize information and insights will need to be ubiquitously operated at this scale too, and at the performance level required for visual analytics.

For many, this transformation is challenging. Not only is the very fabric of business evolving, but there are many technical considerations that must be addressed if organizations are to continue to earn a competitive advantage from their data, while simultaneously giving their business analysts, data scientists, and other data workers the level of enablement and empowerment they need to contribute meaningfully within the data discovery paradigm. These challenges are not limited to the sheer volume of data to manage, but to other key information challenges that affect everything from data integration agility, to governance, to the discovery process itself, and to using data visualizations successfully across the organization. Much of the traditional (and even new) approaches to data architecture have led to complex data silos (or, isolated data copies) that offer only an incomplete picture into data, along with slowing down the ability to provide access or gain timely insights. Further, the control of intellectual property and compliance with many regulations also poses a bevy of operational, regulatory, and information governance challenges. And, the continued push toward self-service with an emphasis on data visualization and storytelling has resulted in the concept that is at the heart of this book: the visual imperative. When buzzwords like “self-service” or “discovery” come up, they imply a certain amount of freedom and autonomy for analysts and data users of all shapes and forms to be able to work with and shuffle through data to earn new insights. These challenges are only exacerbated by the gradual shift to focus on visual analytics, a form of inquiry in which data that provides insight into solving a problem is displayed in an interactive, graphical manner. Today as data architectures morph and evolve into modern data architectures, their success hinges on the ability to enable governed data discovery coupled with high-performance, speed, and earned competencies in how to leverage meaningful data visualization.

While this text is largely nontechnical, this will undoubtedly be by far the most technical chapter of the book, as we explore key information challenges, architectural considerations, and necessary elements of information management and governance that are top-of-mind for many. That said, I will endeavor to break down these concepts and make them as approachable as possible for those not well-oriented with things like discovery-oriented data architectures, while still adding substance and new learning to those who are.

10.1. Key information challenges for data discovery

Future business successes and discoveries hinge on the ability to quickly and intuitively leverage, analyze, and take action on the information housed within data.

Today’s analytic challenges can be separated into three distinct categories: the integration challenge, the management challenge, and the discovery challenge. The answer to these challenges, however, is not the development of new tools or technologies. In fact, the old ways—replication, transformation, or even the data warehouse or new desktop-based approaches to analytics—have met with limited or siloed success: they simply do not afford an agile enough process to keep up with the insurgence of data size, complexity, or disparity. Nor should companies rely on the expectation of increased funding to foster additional solutions. Rather, they should turn to collaborative and transformative solutions that already exist and that are rapidly gaining adoption, acceptance, and use case validation.

Core data challenges have noted that existing data tools and resources for analysis lack integration—or unification of data sources—and can be difficult to both disseminate and maintain (both in terms of deployment and maintaining licensing and upgrades) (Higdon et al., 2013). Further, research literature and testimonies describe another research-impeding challenge: the management challenge posed by defining access rights and permissions to data, addressing governance and compliance rules, and centralizing metadata management. Finally, balancing the need to enable freedom with new data sources and data discovery by the business, while controlling consistency, governing proper contextual usage, and leveraging analytic capabilities are other challenges becoming increasingly in need of mitigation. In this section we will review each of these challenges, and then offer more in-depth solutions in the section after.

10.1.1. The integration challenge

Having access to data—all data—is a requirement for any data-driven company, as well as a long-standing barrier. In fact, a core expectation of the scientific method—according to the National Science Board data policy taskforce—is the “documentation and sharing of results, underlying data, and methodologies (National Science Board, 2011).” Highly accessible data not only enables the use of vast volumes of data for analysis, but it also fosters collaboration and cross-disciplinary efforts—enabling collective innovation.

In discovery, success depends largely on reliable and speedy access to data and information, and this includes information stored in multiple formats (structured and unstructured) and research locations (on-premise, remote premises, and cloud-based). Further, there must exist the ability to make this data available: to support numerous tactical and strategic needs through standards-based data access and delivery options that allow IT to flexibly publish data. Reducing complexity—smoothing out friction-causing activities—when federating data must also be addressed, and this requires the ability to transform data from native structures to create reusable views for iteration and discovery.

Ultimately, the ability to unify multiple data sources to provide researchers, analysts, and managers with the full view of information for decision-making and innovation without incurring the massive costs and overhead of physical data consolidation in data warehouses remains a primary integration challenge. Thus it is a pertinent barrier to overcome in the next-generation of data management. Further, this integration must be agile enough to adapt to rapid changes in the environment, respond to source data volatility, and navigate the addition of newly created data sets.

10.1.2. The management challenge

Another challenge is the guidance and deposition of context and metadata, and the sustainment of a reliable infrastructure that defines access and permissions and addresses various governance and compliance rules appropriate to the unique needs of any given industry.

Traditional data warehouses enable the management of data context through a centralized approach and the use of metadata, ensuring that users have well-analyzed business definitions and centralized access rights to support self-service and proper access. However, in highly distributed and fast changing data environments—coupled with more need for individualized or project-based definitions and access—the central data warehouse approach falls short and prioritizes the need of the few rather than the many. For most companies, this means the proliferation of sharing through replicated and copied data sets without consistent data synchronization or managed access rights.

In order to mitigate the risks associated with data, enterprise data governance programs are formed to define data owners, stewards, and custodians with policies to provide oversight for compliance and proper business usage of data through accountabilities. The management challenges for data environments such as these include, among others: permission to access data for analysis prior to integration, defining the data integration and relationships properly, and then determining who has access permissions to the resulting integrated data sets. These challenges are no different for data warehousing approaches or data federation approaches; however there is a high degree of risk when environments must resort to a highly disparate integration approach where governance and security are difficult—or nearly impossible—to implement without being centralized.

Management challenges with governance and access permissions are equally procedural and technological: without a basic framework and support of an information governance program, technology choices are likely to fail. Likewise, without a technology capable of fully implementing an information governance program, the program itself becomes ineffective.

10.1.3. The discovery challenge

Finally, a third information challenge could be referred as a set of “discovery challenges.” Within these challenges are balancing the need to enable the discovery process while still maintaining proper IT oversight and stewardship over data—or, freedom versus control (see Box 10.1)—which is different than the information or management challenge in that it affects not only how the data is federated and aggregated, but in how it is leveraged by users to discover new insights. Because discovery is (often) contingent on user independency, the continued drive for self-service—or, self-sufficiency—presents further challenges in controlling the proliferation generated by the discovery process as users create and share context. A critical part of the challenge, then, is how to establish a single view of data to enable discovery processes while governing context and business definitions.

Discovery challenges go beyond process and proliferation, too, to include further challenges in providing a scalable solution for enabling even broader sources of information to leverage for discovery, such as data stored (and shared) in the cloud. Analytical techniques and abilities also bring additional challenges to consider, as the evolution of discovery and analysis continues to become increasingly visual, bringing the need for visualization capabilities layered on top of analytics. Identifying and incorporating tools into the technology stack that can meet the needs of integration, analytics, and discovery simultaneously is the crux of the discovery challenge.

10.2. Tackling today’s information challenges

By embracing a data unification strategy through the adoption and continued refinement and governance of a semantic layer to enable agility, access, and virtual federation of data, as well as by incorporating solutions that take advantage of scalable, cloud-based technologies that provide advanced analytic and discovery capabilities—including data visualization and visual analytics—companies can continue on their journeys to becoming even more data-capable organizations.

10.2.1. Choosing data abstraction for unification

Data abstraction through a semantic layer supports timely, critical decision-making, as different business groups become synchronized with information across units, reducing operational silos and geographic separation. The semantic layer itself provides business context to data to establish a scalable, single source of truth that is reusable across the organization. Abstraction also overcomes data structure incompatibility by transforming data from its native structures and syntax into reusable views that are easy for end users to understand and developers to create solutions. It provides flexibility by decoupling the applications—or consumers—from data layers, allowing each to work independently in dealing with changes. Together, these capabilities help drive the discovery process by enabling users to access data across silos to analyze a holistic view of data.

Further, context reuse will inherently drive higher quality in semantic definitions as more people accept—and refine and localize—the definitions through use and adoption. The inclusion of a semantic layer centralizes metadata management, too, by defining a common repository and catalog between disparate data sources and tools. It also provides a consolidated location for data governance and implementing underlying data security, and centralizes access permissions, acting as a single unified environment to enforce roles and permissions across all federated data sources.

10.2.1.1. Digging into data abstraction

Data abstraction—or, as it is also referred to, data virtualization (DV)—is being recognized as the popular panacea for centralization, tackling challenges for manageability, consistency, and security. For database administrators, data abstraction is good for data management.

At a conceptual level, data abstraction is where a data object is a representation of physical data and the user is not (nor needs to be) aware of its actual physical representation or persistence in order to work with that object. The data abstraction becomes a “mapping” of user data needs and semantic context to physical data elements, services, or code. The benefits of data abstraction, then, are derived from the decoupling of data consumers and data sources. Data consumers only need to be concerned about their access point, and this allows for managing physical data—such as movement, cleansing, consolidation, and permissions—without disrupting data consumers. For example, a database view or synonym mapped to a physical database table is available unchanged to a data consumer, while its definition may need to change, its records reloaded, or its storage location changed.

Since abstracted data objects are mappings captured as metadata, they are very lightweight definitions. They do not persist any data and therefore are quick to create, update, and delete as needed. Data abstraction is so valuable because of its agility to define quickly and relate data from multiple data sources without data movement and persistence. This also represents fast time-to-value, ease of updating and dealing with change, and poses less risk to the business.

The growing reality is that there are more and more data sources of interest available for companies to manage. Integration and consolidation can no longer keep up with the demands of a single repository of integrated, cleansed, and single version of the truth (SVoT). Whenever a technology becomes too complex or numerous to manage, abstraction is the solution to detach the physical world from its logical counterpart. We have seen this trend in nearly every other layer in the technology stack; storage area networks manage thousands of disk drives as logical mount points, and network routing and addresses are represented by virtual local area and private networks (VLAN and VPN). Even operating systems are now virtualized as hypervisors running on servers in the cloud. Databases are no different when it comes to the benefits of abstraction.

With a single data access point—whether persisted or virtualized—companies can ensure data consistency and increase quality through reusability and governance to better monitor and enforce security in a single location, while providing data consumers with simplified navigation.

10.2.1.2. Putting abstraction in context

On the heels of centralization comes the concept of context. A semantic context layer is defined as an abstraction layer (virtualized) where some form of semantic context—usually business terminology—is provided to the data abstraction. Virtualizing database tables or files does not provide semantic context if the virtual data object still represents its original application specific naming of data elements. Semantic context exists when the virtualized data objects represent the context in which the user—or, business user—needs to work with the data. Semantic context layers are considered to be “closed systems” when they are embedded into other applications that benefit from having centralized semantic context and data connectivity, such as in BI tools.

Semantic context layers can exist without virtualized databases. Once again, this centralized repository of business context is used to represent data elements of underlying disparate databases and files. From the users’ perspective, the data objects are in familiar business context and the proper usage becomes inherent, while metadata is used to mask the complexity of the data mappings. This is why information delivery applications that have user self-service capability and ad-hoc usage must rely on an abstracted translation layer. Additionally, exposing these “business data objects” drives reusability and therefore consistency across information applications and business decisions, while minimizing rework and the risk of reports referencing the same context utilizing different code.

Another benefit of a semantic context layer is its ability to handle the realization that SVoT is highly unlikely. Realistically, there are multiple perspectives of data, as multiple business context(s) (or abstractions) can be created on the same set of base data. This enables more business specific data objects to be created without having data duplication and transformation jobs to manage. An example is different business interpretations of a customer depending on the business unit or process involved. While data from several operational sources are integrated, the perspectives of a financial customer, sales customer, order management customer, or customer support customer may all have slight variations and involve different attribution of interest to that particular business unit or process.

10.2.1.3. The takeaway

Ultimately, data abstraction is a technique that is a fast and flexible way to integrate data for business usage without requiring data migration or storage. The inclusion of a semantic context layer focuses on business consumption of abstracted data objects in a single, centralized access point for applications within the system where the data stays firmly ensconced in business context.

10.2.2. Centralizing context in the cloud

The growing amount of data not only emphasizes the need for integration of the data, but for access and storage of the data, too. Cloud platforms offer a viable solution through scalable and affordable computing capabilities and large data storage—an Accenture research report that was released in 2013 predicted the cloud trend aptly, stating that cloud computing has shifted from an idea to a core capability, with many leading companies approaching new systems architectures with a “cloud first” mentality (Accenture, 2013). More recently, the International Data Corporation’s (IDC) Worldwide Quarterly Cloud IT Infrastructure report, published in October 2015, forecasted that cloud infrastructure spending will continue to grow at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.1% and reach $53.1 billion by 2019 with cloud accounting for about 46% of the total spending on enterprise IT infrastructure (IDC, 2015). This growth is not limited to the scalability and storage cost efficiency of the cloud, but is also influenced by the ability to centralize context, collaborate, and become more agile. Taking the lead to manage context in the cloud is an opportunity to establish much-needed governance early on as cloud-orientation becomes a core capability over time.

With the addition of a semantic layer for unification and abstraction, data stored on the cloud can be easily and agilely abstracted with centralized context for everyone—enabling global collaboration. A multitude of use cases have proven that using the cloud drives collaboration, allowing companies’ marketing, sales, and research functions to work more iteratively and with faster momentum. Ultimately, where data resides will have a dramatic effect on the discovery process—and trends support that eventually more and more data will be moved to the cloud (see Box 10.2). Moving abstraction closer to the data, then, just makes sense.

10.2.3. Getting visual with self-service

Providing users with tools that leverage abstraction techniques keeps data oversight and control with IT, while simultaneously reducing the dependency on IT to provide users with data needed for analysis. Leveraging this self-service (or, self-sufficient, as I defined it in chapter: From Self-Service to Self-Sufficiency) approach to discovery with visual analytic techniques drives discovery one step further by bringing data to a broader user community and enabling users to take advantage of emerging visual analytic techniques to visually explore data and curate analytical views for insights. Utilizing visual discovery makes analytics more approachable, allowing technical and nontechnical users to communicate through meaningful, visual reports that can be published (or shared) back into the analytical platform—whether via the cloud or on-premise—to encourage meaningful collaboration. Self-sufficient visual discovery and collaboration will benefit greatly from users not having to wonder where to go and get data—everyone would simply know to go to the one repository for everything.

While traditionally most organizations have relied heavily on explanatory and reporting graphics across many functional areas, there are significant differences in these types of visualizations that impact the ability to visually analyze data and discover new insights. Traditional BI reporting graphics (the standard line, bar, or pie charts) provide quick-consumption communications to summarize salient information. With exploratory graphics—or, advanced visualizations (such as geospatial, quartals, decision trees, and trellis charts)—analysts can visualize clusters or aggregate data; they can also experiment with data through iteration to discover correlations or predictors to create new analytic models. These tools for visual discovery are highly interactive, enabling underlying information to emerge through discovery, and typically require the support of a robust semantic layer.

10.3. Designing for frictionless

Friction, and the concept of frictionless, was introduced earlier in chapter: Improved Agility and Insights Through (Visual) Discovery. To revisit it here briefly, friction is caused by the incremental events that add time and complexity to discovery through activities that slow down the process. These are activities that IT used to do for business users and which add time and complexity to the discovery process, interrupting efficiency and extending the time to insight. For example, in discovery, these friction-laden activities could be requesting access to new data or requesting access to an approved discovery environment.

Friction, then, is a speed killer—it adds time to discovery and interrupts the “train of thought” ability to move quickly through the discovery process and earn insight. Frictionless is the antithesis of friction. As friction decreases, so, too, does time to insight (speed increases). Therefore, to decrease friction is to increase the speed at which discoveries—and thus insights—can be made. That is the concept of frictionless—to pluck out as many of those interruptions as possible and smooth out the discovery process.

We can conceptualize iterative discovery as a continuous loop of five compounding activities, where the goal is to remove as much friction from the process as possible (see Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 This Visual Illustrates the Five Compounding Steps in an Iterative, Frictionless Discovery Process

In the first stage, analysts get access and begin working with data. While they cannot yet justify the value of the discovery process as insights are yet to be discovered, they nevertheless expect access to data in a low barrier process that requires high-performance (like speed, access, and diversity of data source). After accessing data, analysts begin to explore and require tools to quickly assess, profile, and interrogate data—including big data. As they move into blending, analysts require agility and access to integrate various sources and types of data to enhance and unify it, and ultimately enrich insight opportunities.

These first three steps are the initial preparation phases that fuel discovery (though they typically take the most time). Only after data can be accessed, explored, and blended, can analysts begin to build data and analytic models and visually work with data. Once insights are discovered (or not), analysts can then collaborate with other users for verification to find additional insights, story-tell, and cross-learn. This collaboration is how analysts share knowledge; validate insight accuracy and meaningfulness; and leverage peer knowledge and insights to avoid potential errors and inaccuracies. It is also the governance checkpoint in the discovery process to engage in postdiscovery assessment processes. We will discuss these checkpoints in the following sections.

10.4. Enabling governed data discovery

Business-driven data discovery is becoming fundamental for organizations to adapt to the fast-changing technology landscape in nearly every industry. Companies must explore, iterate, and extract meaningful and actionable insights from vast amounts of new and increasingly diverse internal and external data. A formalized discovery process fills the gap between business and IT: subject experts are empowered in their business domain, and IT actively supports and takes a data management role in facilitating the needs of the business. Without recognizing and governing this process, business users struggle—or worse, to work around polices for data governance and IT data management.

Recent technologies, like Apache Hadoop, have significantly lowered the technical barriers to ingesting multiple varieties and significant volumes of data for users. However, one of the biggest barriers to discovery is still providing controlled access to data, and data governance remains a charged topic. To achieve the maximum benefits of discovery, analysts must be able to move quickly and iteratively through the discovery process with as little friction—and as much IT-independence—as possible. Empowered with new discovery tools, more data, and more capabilities, ensuring data and analytics are both trustworthy and protected becomes more difficult and imperative. This becomes a careful balance of freedom versus control, and brings the role of governance to the forefront of the discovery conversation.

Data governance is not a one-size-fits-all set of rules and policies: every organization (or even various groups within organizations) requires its own rules and definitions for discovery for its unique culture and environment. Enabling governed data discovery begins with robust and well-planned governance to support rather than hinder discovery. Likewise, governance programs will continue to evolve, and discovery-oriented policies should be designed with the least amount of restrictions upfront as possible, and then refined iteratively as discovery requirements become further defined. This section discusses and explains how to manage the barriers and risks of self-service and enable agile data discovery across the organization by extending existing data governance framework concepts to the data-driven and discovery-oriented business.

10.4.1. Governance checkpoints in discovery

Data governance frameworks rely on the active participation of data owners, data stewards, and data management (IT) as cornerstones of accountability, knowledge, and implementation of policies. In my work with Radiant Advisors, we identified three critical checkpoint areas in the data discovery cycle where data governance should be in place to enable as self-sufficient and frictionless an experience as possible (Figure 10.2).

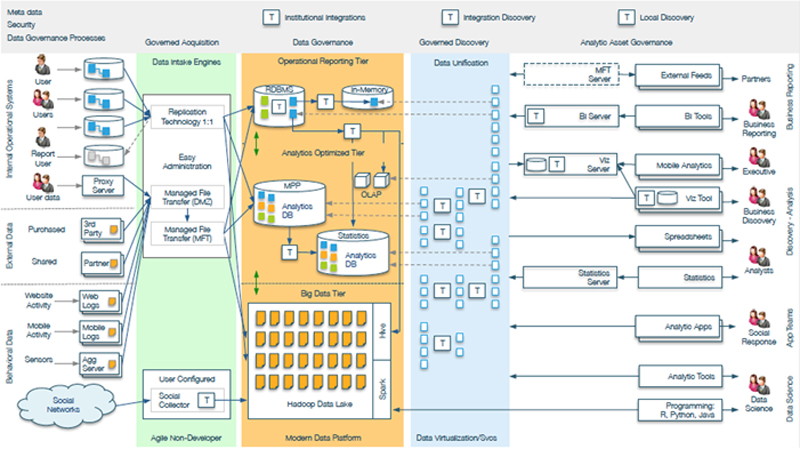

Figure 10.2 Radiant Advisors’ Modern Data Platform Enabling Governed Data Discovery

The first checkpoint opportunity is at the beginning of data discovery. This involves streamlining data access to data with the ability to grant, chaperone, and receive access rights, thereby enabling faster data exploration in an approved discovery environment. The second collaboration checkpoint occurs after discovery and is necessary to verify and validate insights, and determines the designation of context for new data definitions, relationships, and analytic models. In the third and last checkpoint, governed discoveries are intended for the purposeful and appropriate sharing of insights (both internally and externally) to ensure that they are leveraged, continued, and communicated appropriately. Now, we will explore each of these areas in detail.

10.4.1.1. Checkpoint #1: to enable faster data exploration

Data discovery begins with an analyst’s need for unfettered access to search for insights hidden within untapped data, relationships, or correlations. This need for access is compounded by the expectation for quick, unrestricted access to data in discovery environments while working through the discovery process. For faster data exploration, policies should be designed related to the discovery environment itself—how, when, where, and under what circumstances analysts should leverage personal desktops, temporary discovery workspaces, virtual environments, or even cloud-based environments. Each environment has its set of benefits and drawbacks, and some environments may be rendered inapplicable simply because they are not already a part of an organizational data infrastructure and cannot justify additional effort or expense.

First, from Microsoft Excel to the current generation of easily adopted desktop discovery tools, the personal desktop is a long-standing discovery environment. Its use for discovery grants instant environment access for users but is inherently limited by space restrictions and likely unable to facilitate all data needs (see Box 10.3) and requires data download or extraction. Also, personal desktop use for discovery must also be policed by supplemental security policies (like desktops not allowing data be taken off-site, or procedures for IT remote wipe capabilities). Beyond personal desktops, users may request a temporary workspace within an existing database (like a sandbox or section of the data lake) to act as an isolated and quarantined area for discovery. Of course, to leverage these low technology barriers for discovery, the database must already exist in the architecture. If not, a data virtualization discovery environment could be designed to access and integrate disparate heterogeneous physical databases. However, again if these are not already part of the existing technology architecture they can be timely and cost-intensive to establish. Finally, cloud-based discovery environments can be sanctioned for low-cost on-demand discovery environments. While beyond personal desktops clouds may be the fastest time to enable a discovery environment, they will likely come with other governance implications, such as moving internal data to a cloud environment or the eventual inability to bring external data back into the enterprise until it has been validated. For any governed discovery environment, there must be timelines in place for permitted data access in discovery. Once this timeframe has expired, processes and rules for properly purging sample data sets must be established. There is more than one way for discovery to exist and prosper in the enterprise, and comprehensive governance ensures that friction is able to be contained by data management.

Beyond policies for discovery environments, access policies should also be defined for individual data source categories. These include requesting access to internal systems (relational databases, proprietary databases, web logs, etc.), third party acquired data sets, public data (eg, social), and other Internet data sources. The role of personally-collected, independent user data in discovery will also require consideration for its validation and restriction, as will policies and processes for access related to fetching data from disparate sources.

Defining policies for data access and discovery environments may expand the roles of existing data owners and data stewards, as well as bring to light the possibility of defining these new roles for new types of data, like social data and data generated from the Internet of Things (IoT). An interesting paradigm for data ownership and stewardship is that the analysts doing discovery may already be the unofficial stewards of previously “unowned” social or IOT data. While social data acquisition vendors and solutions may already address concerns regarding privacy and retention in social platforms, new data owners and stewards will need to pay close attention to social data used in discovery. Moreover, it will be the data owners’ responsibility to decide and define how (or if) blending of data sets should be created. For instance, there may be situations where data blending is outlawed by data source contracts, or there may be concerns about blending anonymous, invalidated, or other social data with internal data for discovery purposes. The level of governance and veracity of data changes within the realm of big data will depend on the data source, as well as the analyst using the data and the context in which it is being used. There should also be considerations for data masking and decisions on which data fields should be hidden, the level to which data should be obfuscated, and how this impacts the usability of the data for analysis and discovery.

10.4.1.2. Checkpoint #2: at the time of insight

Once users have been given data and access to a discovery environment and an insight has been discovered—whether a new context or definition, extending an existing data model, or a new correlated subgroup of data of interest—a governance checkpoint should be in place for verification and validation. Before an insight can be broadly consumed and leveraged throughout the enterprise, it must be reviewed to ensure it is true, accurate, and applicable.

This postdiscovery governance assessment is the catalyst that begins the movement of an insight from discovery to institutionalized definition. A collaborative approach to verification is one option. In this approach an insight is sourced among peers, subject matter experts, and others in the organization to validate that it is meaningful, correct, and free of errors. Data stewards may also be involved to build consensus on definition(s) and verify context and where context is applicable. Data owners (and/or stewards) may also be asked to bless insights with approval before they are shared or consumed (meanwhile the insight remains in local usage adding value to the business in quarantine until this assessment is completed).

Following postdiscovery assessment comes postdiscovery designation of new definitions and context. This is twofold: new context should be given designation within the enterprise (local vs global) along with a shelf life (static vs dynamic) for applicability. To the former, a continuum of enterprise semantic context exists that ranges from local, to workgroup, to department, division, line of business, or enterprise. The more global the definition in the enterprise, the more broadly the data will be consumed and a data owner should be involved with the verification and designation process. To the latter, an insight may only be valid for a project or other short-term need, or it may be a new standard within long-standard enterprise key performance indicator (KPI) metrics. Over time, as underlying data changes the definitions and integrations behind the context, the discovery’s shelf life will be an important determinant in how data management integrates the discovery.

Being discovery-led enables the decoupling between business users and data management. However, once postdiscovery governance is complete and the designation of semantic context defined, data management must decide how to manage the definition going forward. Data management will make the decision whether the discovery should live physically or virtually in the integration architecture (ie, move an abstracted discovery into a physical database, or take a discovery done physically in a lake and abstract it), and how best to shift a discovery from a discovery environment to a production environment and maintain ongoing data acquisition so that a long-term insight will continue to be valid.

10.4.2.3. Checkpoint #3: for institutionalizing and ongoing sharing

Once an insight has been discovered, vetted by the data owners and stewards, and moved under the purview of data management, a governance checkpoint should be included before new discoveries are communicated into the organization. While this may already exist as part of the normal governance process, consider these three key areas to focus on as checkpoints for new discoveries.

First is capturing newly discovered insight metadata (from reasoning, to logic, to lineage) for search and navigation in order to ensure that the people who need the data can find it—including other (and future) discoverers. Data owners need to define the continued access and security of the insight, including its use in exchange with partners and suppliers. This is a valid point to consider because while discovery may have identified a special cluster or group, the new data may be unable to be shared with others externally. Finally, with transparency both internal and external to the organization continuing to earn a sharpened focus in an increasingly data-dependent culture, additional policies and guidelines on how data can be shared and through what means should be defined. One relevant example is how data is shared via live, public social streams, and decisions on what—if any—filters should be in place. Internal collaboration technologies and/or platforms are likely to be required, too.

10.5. Conclusions

Evolving existing data governance programs to enable architected governed data discovery provides the opportunity to leverage proven principles and practices as guidelines to provide governance-in-action that effortlessly empowers discovery-oriented analysts, project, and business needs instead of restricting them unnecessarily due to a lack of a well thought out approach. The new discovery culture brings along with it a set of expectations by analysts who want to move with agility through data that is acquired from all types of data in order to iterate, integrate, and explore a frictionless discovery process. Designing data governance to enable governed data discovery should be approached as an agile and collaborative process between data owners, users, and IT with a common goal. In order for discovery to reach its maximum potential, there is an inherent amount of freedom required, and policies should enable speed, access, and exploration, rather than restrict it. Therefore, as data governance policies are defined, they should focus on writing rules that are looser and higher-level, while providing the intent and the framework for how to conduct discovery.

Of course, data governance is a continuously evolving process that identifies new policies, modifies existing ones, and retires policies and roles as they become obsolete or out-of-date. As companies begin to enable governed data discovery across the organization, they should expect this to be a starting point. Like discovery itself, new data governance policies will also be discovered based on the iterative discovery model and data governance principles. Fortunately, the data governance evolution is being aided by tools and products in the market that are also tackling these challenges for their customers to produce the necessary capabilities and artifacts being required by data governance programs. Therefore, a tool’s data governance capabilities are becoming an essential part of evaluations and no longer optional to its primary purpose. With some tools, you will find a thorough data governance strategy that infuses your in-house program with new ideas and proven best practices.

10.6. Anatomy of a visual discovery application

When we begin to think about architecting for visual discovery, perhaps it is more efficient to pick through the pieces necessary to build the correct framework, rather than trying to assemble it from the ground up. We can consider this as a more surgical approach, if you will, to pull apart the anatomy of a visual discovery application, based on the several tightly coupled components (or interdependent layers) between the data and the end user that are required to leverage advanced analytics algorithms and advanced visualizations for business analytics.

Some companies will have data engineers, mathematicians, and even visualization experts working with their own tools to create advanced analytic visualizations because a specific solution might not otherwise exist in the market. However, this is a slow, costly, and risky approach (for maintainability) that may be undertaken by companies that either have the infrastructure to support the initiative, or possibly by those that simply do not realize the risks and complexity involved. Typically, a company will have one or two layers already to leverage and will instead seek out the advanced visualization or analytics tool, and then create more custom code to move and transform the data between data stores. Here are the core three layers of architecture needed for a visual discovery application:

Advanced visualizations layer: Basic visualizations are simply not powerful enough to see the richness and colors within massive amounts of data. While there are many basic and proven chart and graph types available in common tools, the ability to see more data with the most visual intuitive diversity is needed. Advanced data visualization types employ “lenses” to componentize the visual, yet still have it tightly integrated with the output of the proper data analytics routine.

Advanced analytics layer: This layer and capability represents the complexity of employing the correct analytic routines, SQL data access, and mapping the output with the advanced visualization. Shielding the customer from complex SQL (ie, both correct and properly tuned to execute well) is highly valuable to the user experience.

Data access layer: The reality for most companies is that the required data sets are still in disparate systems—possibly in a data mart or data warehouse. There can be data integration routines developed to consolidate the needed data into a consolidated database or analytic sandbox; however this has proven to be highly inefficient in dealing with system/data volatility and incurring additional time and cost. The appropriate solution is to have a data virtualization layer with proper implementation to maintain a data object repository.

10.7. The convergence of visual analytics and visual discovery

Over the past few years, the data industry has become increasingly visual with the maturity of robust visualization tools geared toward enriching visual analysis for analytics and visual data discovery. In many ways, visual discovery has been seen as the catalyst to breaking open the potential of data in the most intuitive and self-service way possible. However, as an interactive process of exploration that embodies the use of visual technologies to augment human capabilities and prompt the user to uncover new insights and discoveries, there is still much to define in terms of the use cases for and core competencies needed in visual data discovery. Likewise, there are still lingering ambiguities over the nuances, roles, and processes of visual analysis as a function that uses visual data representations to support various analytical tasks.

While this chapter has touched lightly on data visualization and visual analytics, the next chapter will dive into this in more detail with the introduction of the Data Visualization Competency Center™.