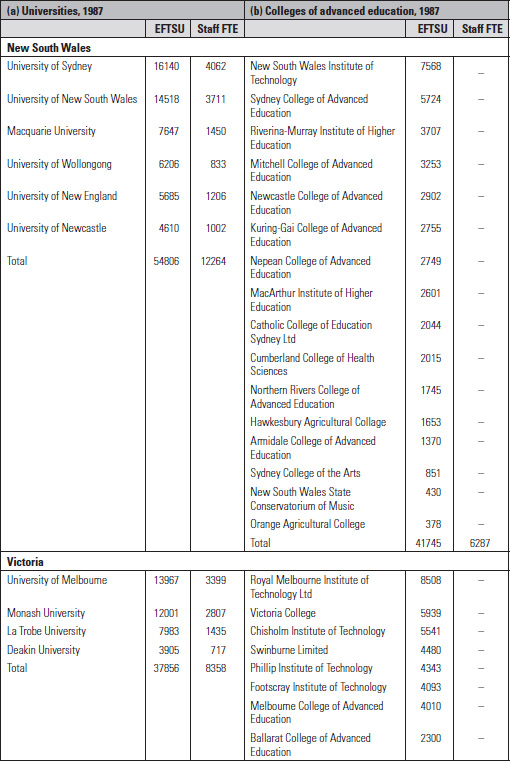

Table 1: Universities and colleges of advanced education, 1987

Dawkins’ time at Roseworthy and the University of Western Australia coincided with a remarkable expansion of higher education. In 1965 there were just 83 000 students undertaking degree courses in the country’s ten universities, with another 30 000 pursuing similar qualifications offered by teacher training colleges and a variety of technical and specialist institutions. Ten years later there were nineteen universities, the college sector had been transformed, and higher education enrolments had risen to 273 000.1

This was a time when Australians seemingly could not get enough education and were prepared to pay ever more money for it through their taxes, so that the Commonwealth assumed full responsibility for funding higher education, embarked on a major construction program, abolished fees and liberalised student allowances. The increase in public expenditure on all forms of education—it rose from 2.64 per cent to 5.88 per cent of GDP over the decade—was fuelled by a rising population enjoying greater prosperity, which allowed more school students to complete secondary education and lifted their aspirations to continue with further study. Here, and in other advanced economies, governments augmented provision not simply to meet demand but to encourage it. They saw education both as an investment in human capital that would lift productivity and—as Dawkins did—as a means of enhancing citizenship and broadening opportunity.2

These expectations were so powerful and pervasive that they continued to operate long after their economic foundations crumbled. Bill Hayden’s cuts to public expenditure in 1975, the last year of the Whitlam government, and the reduction in higher education outlays announced by Malcolm Fraser in 1976 were seen as a temporary interruption of the virtuous cycle of educational attainment. Prescient observers could see that education was off the boil. Peter Karmel, the country’s most influential and astute educationist, warned that population growth had slowed with the economic downturn, participation had tailed off and there was ‘a general disillusionment’ with the supposed benefits of public investment. He foresaw no resumption of growth but rather a ‘steady state’ that would require painful readjustment.3

As head of the government body responsible for the universities and colleges, Karmel wanted them to understand the mood of ‘widespread disenchantment’. The benefits of higher education for the individual student, society and the economy had been ‘oversold’, and it now operated in ‘an atmosphere of criticism, scepticism and downright hostility’. There were complaints of waste, laxity and the failure to produce graduates with employable skills, and the common response of ‘university people’ to defend existing arrangements was counter-productive: ‘politicians, the press and the general public do not trust academics to be judges in their own causes’.4 Notwithstanding such clear indications that higher education had lost its allure, those who led the country’s universities continued to speak and act as if the government’s stringency was but an aberration their customary arguments would dispel.

They were mistaken. The steady state would last for more than a decade and bring a series of piecemeal expedients that only increased the strain on the sector. In contrast to the steep increase of enrolments between 1965 and 1975, the number of students grew between 1975 and 1985 by just a quarter, while funding remained constant in real terms.5 Adjustment to such dramatically altered fortunes was bound to be difficult, especially in institutions that were accustomed to growth. Their modes of operation were not conducive to rapid change, for they employed tenured academics in a large number of specialised fields who taught courses of up to six years in duration and built up their research with a stock of expensive equipment and extensive collections of materials. Universities, moreover, were self-governing institutions with a high degree of autonomy; academic freedom was integral to their mission. From the time the Commonwealth Government commenced financial support, it was taken as axiomatic that institutions would have ‘full and free independence in carrying out their proper function as universities’.6

That axiom was thrown into question as the country’s universities struggled to adjust to the funding freeze. Both Fraser’s Coalition and Hawke’s first two Labor ministries became increasingly prescriptive, although they stopped short of abrogating university autonomy. It was the reorganisation of the other arm of higher education, the colleges, that laid the foundations of Dawkins’ scheme of a comprehensive Unified National System, for the colleges were cheaper, more attuned to vocational training and more amenable to direction. Their enlarged capacity allowed them to offer courses and degrees that had previously been the preserve of universities, and as they did so they exposed the vulnerability of these more privileged seats of learning.

There were nineteen universities in 1975 and nineteen a decade later. Six of them were founded in the colonial period and opening years of the twentieth century. Sydney (1850), Melbourne (1853) and Adelaide (1874) came first and established an enduring model that departed markedly from the ancient foundations of Oxford and Cambridge and in significant respects from the more worldly Scottish universities. Here the university was created by statute and supported at public expense. Government was exercised by a lay council (or senate)—but in contrast to the civic universities formed in England a little later than these colonial ones, the governing body provided only a weak link to the community it served. Australian universities adopted the architecture, academic dress, ceremonies and customs of older seats of learning, but adapted the practices to their own requirements. They were located in the capital cities, offering both a liberal education and professional qualifications to a predominantly non-resident student body.7

As their names suggest, the later universities of Tasmania (1890), Queensland (1910) and Western Australia (1913) followed the public universities of the United States in putting greater emphasis on serving the needs of their states, but retained the organisational form of the local predecessors.8 All of them developed along the same disciplinary lines, adding new faculties to teach professional degrees—first medicine, law and engineering, then education, dentistry, veterinary and agricultural science, commerce and architecture—but remained small and straitened. The six foundation universities admitted all who met their entry standards, including women by the end of the nineteenth century, but together they had just 15 000 students in 1939 and only 31 000 in 1950.

Three universities established following World War II broke new ground. First, the Commonwealth created the Australian National University (ANU) in 1946 to serve the country’s need for advanced research. Funded from the federal purse far more generously than the state universities, it stimulated them to greater effort. Moreover, ANU used a school structure to facilitate closer interaction between complementary branches of knowledge, although the familiar disciplinary boundaries soon solidified. Then New South Wales created a University of Technology in 1949 to assist that state’s industrialisation, and Victoria followed in 1958 with its own second university, Monash, again conceived as technological in character. Both displayed similar characteristics, more purposeful with greater direction by their executive officers and some experimentation in curriculum and pedagogy, but they soon offered almost the same range of courses and degrees as the older universities.9 Each new departure, it seemed, quickly reverted to the norm.

That was certainly true of the universities fostered by the older ones. A university college was established in 1929 in the fledgling national capital of Canberra, teaching and awarding Melbourne degrees. A college of the University of Sydney began at Armidale in 1938; the University of New South Wales (as the University of Technology became in 1958) seeded colleges at Newcastle and Wollongong, as did the University of Queensland at Townsville. All these regional colleges became autonomous universities, Armidale first as the University of New England (1954), Canberra through amalgamation with ANU (1960), Newcastle in 1965, Townsville as James Cook University (1970) and Wollongong in 1975.10 This was a process of replication similar to that in England, where the civic universities began as colleges of the University of London until they were deemed capable of maintaining appropriate standards.

As new metropolitan universities were added from the 1960s, it seemed that they too would follow this path. By then the existing ones had reached or were approaching enrolments of 10 000 students, a number at which it was thought their coherence was at risk—and so it probably was according to the understanding at that time of the shared experience a university should provide. The University of Sydney, about to impose quotas on all first-year courses, helped plan Macquarie (1964), as the University of Queensland did Griffith (1971), while Flinders (1965) was initially conceived as a southern campus to relieve overcrowding at the University of Adelaide and Murdoch (1973) as a feeder college for the University of Western Australia.11 However, the enterprising professors from the established institutions who planned the additional ones were attracted by the opportunity to strike out anew. They were modernisers who wished to broaden access, provide a richer student environment and offer less specialised courses aligned more broadly to the economic and social needs of the post-war era.

They were particularly attracted to the new ‘plate-glass’ universities then getting under way in Britain in a conscious break from the past. Sussex, York, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Warwick and Lancaster (no attempt here to attach the name of a worthy forebear) were built on the outskirts of smaller conurbations, using large, detached sites to lay out a comprehensive design that gave tangible expression to the goal of an integrated scholarly community. The lecture theatres, classrooms and library were complemented by halls of residence, playing fields, services and facilities, linked by pathways and shielded from motor traffic. These new universities also eschewed faculties and professional courses in favour of schools that grouped the humanities, social science and science to create what a vice-chancellor of Sussex called a ‘new map of learning’.12

Peter Karmel, who moved from a chair of economics at Adelaide to become the founding vice-chancellor of Flinders, proclaimed its intention to ‘experiment and experiment bravely’.13 He was greatly taken by Sussex, as were his counterparts, and while they drew on parallel developments in US colleges of liberal arts and science, they emulated the British foundations in their physical design, school structure and emphasis on a general education. La Trobe (1964) also adopted the idea of allocating all students to a college for greater intimacy. Yet the Australian experiments differed in important respects. Apart from Deakin (1974), they were situated on the edges of the principal cities and their plans for residential halls were not fulfilled, so they competed for the same pool of school-leavers as their established counterparts. A new university in Britain was intended to grow to 3000 students, whereas an Australian one envisaged between 6000 and 10 000. It also included professional courses—Murdoch began with veterinary science, Flinders soon had a medical school, and a law course was a common desideratum.14 As was the case in Britain, not all students responded to the inter-disciplinary foundation studies. For that matter, some of the academics who were expected to join in such collaborative ventures found the exercise uncongenial.

In Britain it was said that the new universities’ phase of experiment would last no more than ten years, probably only five. One of Macquarie’s founders remarked that ‘A university is like a batch of cement’—the material commonly used on these green field sites—‘it sets hard quickly’.15 The new universities began with clear advantages: they recruited younger staff with better qualifications, a high proportion of them from overseas. But before long scientists were arguing that their students should be exempted from breadth requirements, economists pressing for their own degrees and other professors seeking budgetary control of disciplinary programs. These universities were also hit hard when the government turned off the tap in the mid-1970s: their plans for sequential development were truncated, leaving them lopsided and making it difficult to sustain many of their innovative practices.

The formation of the new universities came, moreover, just as an alternative form of higher education was created. In 1959, after Robert Menzies accepted the recommendation of the Murray committee that the Commonwealth assist the states in supporting and building up their universities, he established the Australian Universities Commission (AUC) to provide advice on their future needs. The magnitude of its initial recommendations alarmed him, so he instructed the chair, Sir Leslie Martin, to investigate the ‘future development of tertiary education in Australia’, that generic term signalling his expectation of alternative arrangements allowing greater economy. The Martin committee decided that the solution lay in diverting much of the increased demand from universities to less costly colleges. They would be built up to teach a range of vocational courses with a leavening component of general education, freeing the universities to concentrate on academic disciplines. This was the binary system—a term coined in Britain, which created its own dual system of universities and polytechnics at this time—that was adopted in 1965.16

It rested from the beginning on insecure foundations. Martin’s ideal of the university as a place of pure research and higher learning was contradicted by the actuality of the Australian university, which had long embraced professional courses and was continuing to add them in such fields as pharmacy, accountancy, management and town planning. The augmented colleges were hardly likely to accept his prescription that they restrict their awards to diplomas, refrain from conducting research and content themselves with applying the discoveries made in the universities to practical uses. Martin’s recommendation that his commission be expanded to police the binary system was not accepted, and a separate Advisory Committee on Advanced Education (the term coined by John Gorton, who was minister in charge of education at this time) served the ambitions of the colleges. The teacher training colleges became part of advanced education in 1973 as it expanded to serve the professionalisation of occupations in health, business, media, new technologies and more applied forms of the social sciences.17

By this time some colleges were awarding their own degrees and even teaching postgraduate courses. The Fraser government tried to control the blurring of the binary divide by creating a Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission in 1977, but retained separate advisory councils for the universities and colleges that continued to advance their competing claims. The subsequent addition of a third council for technical and further education (TAFE), as that sector expanded its provision of diplomas and associate diploma, caused additional friction.18

Less costly than the new universities, the colleges attracted students who might otherwise have built university numbers; 70 per cent of the increase in higher education enrolments between 1977 and 1987 occurred in the colleges of advanced education (CAEs; see table 1). Having begun as state instrumentalities, they allowed much closer direction. For although the colleges were given their own governing bodies, these were dominated by government nominees; and in keeping with their origins as part of the public service, college directors held greater power than university vice-chancellors. The colleges also remained subject to the oversight of state coordinating authorities. It was therefore possible for the Fraser government’s ‘razor gang’ to impose a drastic remedy in 1981 after the demand for teachers fell away: most of the training colleges were merged forcibly into consolidated entities teaching a wider range of vocational courses.19

The largest and strongest of the forty-five colleges operating by the early 1980s were the institutes of technology in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney, flanked by smaller metropolitan and regional technical colleges. As a result of the rationalisation of teacher training, there were substantial multi-campus and multi-disciplinary colleges of advanced education in the five principal cities as well as smaller ones in regional centres. Finally, there were specialist colleges teaching agriculture, art, music, pharmacy and health sciences. Unlike the universities, the colleges differed markedly in size and function, but they were united in their resentment of the privileges of the universities—self-governing, self-accrediting, better funded and with provision for research—as well as the unbending superiority complex of those who worked in them.

The mood in the universities was defensive and introspective. The titles of books that appeared at this time—Higher Education in a Steady State (1978), Academia Becalmed (1980), The End of a Golden Age (1981), A Time of Troubles (1981)—attest to the debilitating effects of the abrupt change in their fortunes.20 Contributors to such colloquia bemoaned the deterioration of facilities as funding for capital works dried up, the obsolescence of equipment and difficulty of responding to changes in demand when more than 85 per cent of expenditure went on salaries. They complained of an ‘incremental creep’ in salary costs as long-serving and better-paid academics blocked the recruitment of ‘new blood’, and the inflexibility of a tenure system that protected them at the expense of more flexible appointments on a fixed-term basis. Above all, they registered the breakdown of trust between universities and government now that education was no longer seen to possess the ‘magical qualities’ attributed to it during the era of growth.21

The reduced confidence in the country’s universities prompted some within them to reflect on their character, composition and operation. Of those who specialised in the study of higher education, Don Anderson was perhaps most influential—and misrepresented—with his finding that the removal of financial barriers to entry had done little to reduce inequality. As he explained, the inequality persisted because of the advantages enjoyed by those who attended private schools in the fiercer competition for university places.22 Less often noticed was Anderson’s observation that the social mix of the Australian university was nevertheless far more representative of the population at large than in Europe or North America, particularly of families of modest means and educational attainment. Even before Whitlam abolished fees in 1973, it was cheaper and, since most students lived with parents, living costs were lower. Moreover, there was much greater allowance for part-time and external study. The converse of this ease of access was a vocational orientation: the Australian university had little concern with the intellectual and moral cultivation associated with a full-time, residential experience since its chief function was training the professions. It sacrificed liberality for equity and utility.23

Anderson tracked the consequences in a longitudinal study of 3000 students in engineering, law, medicine and education. He found their courses narrow and specialised, and judged the average graduate to be ‘culturally illiterate’. Yet while these students began their preferred degree with a strongly vocational motivation, took little interest in extracurricular activities and mixed mainly with fellow trainees, many developed intellectual interests by the end of their studies and regretted the absence of a broader educational experience. They were denied this opportunity because those who taught them, and the professional bodies that accredited their degrees, insisted that the overriding objective was to impart the specialised knowledge and skills needed for professional practice.24

Premature specialisation and a narrow curriculum were entrenched weaknesses of the Australian university, repeatedly deprecated by champions of a more liberal education, yet reinforced by an organisational structure that allowed each faculty to control its own degree and prescribe the course of study. The experiments of the new universities were an attempt to overcome this rigidity, their difficulty in maintaining them an indication of the strength of the vocational impulse. A further problem was that with the historical ease of access to the Australian university came high wastage. Partly because it was so easy to get in, it was easy to drop out; and part-time students and external students were the most likely to discontinue. Here efficiency lost out to equity, and much effort was made during the 1970s and 1980s to improve teaching and student support.

Finally, the university was widely criticised for an autonomy verging on autarchy. Academic control rested historically with the professoriate, each professor in charge of his discipline (the first female appointment to a chair was in 1960) and all the professors joining in collegial decision-making through their membership of the professorial and faculty boards. When the rapid growth that began in the 1960s created much larger numbers of non-professorial academics, the principle of collegiality was extended to departments and, with the ‘god professor’ dethroned, the office of head of department rotated. This more democratic order did not cure the ills of the oligarchy it replaced. Departmental heads continued to press the claims of their own disciplines on the academic board (renamed in recognition of the fact that it was no longer restricted to professors) but were reluctant to intrude in each other’s affairs, for every discipline claimed its own expertise and shared a common interest in resisting interference. The newer universities were less encumbered, their academic committees smaller and more selective, but the large and cumbrous boards of the older universities were jealous of their prerogatives.

How then was the university to be managed? The governing body entrusted responsibility to a vice-chancellor, initially drawn from the professorial ranks, although by this time often recruited from another university, who was expected to guide its academic development, control the funds and maintain relations with government and outside bodies. But the vice-chancellor had very little formally designated power to determine academic policy or exercise management control. The council made all major financial decisions, so he (the first female vice-chancellor was appointed in 1987) needed to retain its confidence, and he was only one voice among many on the academic board and other university committees.

If the enlargement of the university multiplied the number of vested interests, the end of growth made it far more difficult to satisfy all of them. A close observer wrote in 1987 that ‘most vice-chancellors must feel at some time that their universities are essentially ungovernable’, and no doubt Dawkins was not the only minister who felt the same.25 This judgement would have surprised such legendary despots as John Story, who became Vice-Chancellor of the University of Queensland in 1939 while head of the public service and dominated it until retirement in 1960 at the age of ninety, or Sir Philip Baxter, who brooked no dissent at the University of New South Wales from 1953 until 1969, or James Auchmuty of Newcastle, who threatened to eject a professor who argued with him at the academic board—and there were others in that expansive era of whom it was said that not a sparrow fell from a tree but he shot it.26

Strong leadership became more difficult in the steady state. The institutional impulse was to support growth rather than restrain it and to add new things rather than reform the old. A long period of expansion had created a momentum that universities found difficult to check even though resources were no longer available to support it.27 By the 1980s the bigger ones—Melbourne, Monash, New South Wales, Queensland and Sydney—each had annual budgets well over $100 million, along with responsibility for up to 16 000 students and the direction of more than 3000 academic and general staff. Such undertakings required a large administrative cadre, but the professionalisation of university management was not easily reconciled with academic self-management. A bicephalous structure emerged of senior administrators (registrar, bursar and other divisional heads) working alongside the vice-chancellor and a small number of senior academics (deputy and pro vice-chancellors) with delegated areas of responsibility. This executive group attempted to give purpose and effect to an organisation that had long ceased to be a community of scholars but in which the principle of collegiality was still held dear.

Higher education stopped growing in 1975 as the economy slowed. Rising government expenditure and wages increases were driving up inflation even before a sudden spike in the cost of oil spread price rises throughout the international economy and stifled consumer demand. Between 1975 and 1983, Australia’s annual economic growth fell to 2 per cent, with inflation running at 12 per cent and unemployment at 7 per cent.28 The Fraser government sought to restore the country’s fortunes by reducing wages to restore profits and investment, and holding down public outlays to reduce the burden on the private sector. Its decision to relax wage controls after another steep rise in the price of oil suggested Australia could increase its energy exports proved untimely: the second oil shock brought a global recession in the early 1980s and left a weakened domestic economy with a severe balance of payments problem.

It was apparent by now that the difficulties were deep seated. Both inflation and unemployment were high and persistent, and the accepted methods of dealing with them no longer worked. Apart from the fact that fiscal and monetary measures used to ameliorate one problem worked against the other, the international system of fixed exchange rates and financial controls had collapsed; capital was more mobile, and manufacturing industries once anchored to the domestic market were moving to take advantage of lower wage costs in newly industrialising countries. The Labor government would embark on a far-reaching reconstruction of the Australian economy, although any notion that it took office in 1983 with a comprehensive plan that encompassed higher education is unfounded. It dealt with particular problems as they arose and with measures that became part of a grand narrative only as the decade progressed.29

The Hawke government’s initial strategy rested on a Prices and Incomes Accord with the unions, which at that time represented more than half the workforce and had defied the Fraser government’s attempt to control their demands. They would restrain wage claims in order to allow job creation and in return for compensation through increased welfare provision. This arrangement was confirmed at a National Economic Summit held at Parliament House in April 1983 and attended by representatives of the unions, employers and other non-government organisations—but not the education sector. Higher education was considered a component of the ‘social wage’ that secured union acceptance of the Accord, but a subsequent pledge that the government would restrict taxation and expenditure to the present proportion of the GDP ruled out any significant increase in funding—it was the expenditure on training and employment programs for the large number of school-leavers unable to find work that rose steeply during the 1980s.30

The first break with this consensus came at the end of the year with the floating of the dollar and lifting of exchange controls, followed by removal of restrictions on bank lending and the licensing of foreign banks. That was certainly a momentous change, for by exposing the financial sector to market forces it made regulation of other sectors of the economy more fragile, and was quickly interpreted as the first instalment of a process of reform that would extend to trade, industry, the labour market, the tax system, the public sector and education.31 Reform in this context meant removal of impediments to the operation of the market and efficient allocation of resources. The term carried attractive connotations of improvement, and is now commonly attached to any government measure, whether progressive or regressive; but its application to the program of economic liberalism has dubious validity since the extension of that doctrine’s postulate of acquisitive individualism to every sphere of human activity swept aside the moral ethos of social solidarity that has been associated with reform ever since the Reformation. It is a particularly inappropriate term for the changes that John Dawkins made to higher education, where the limited market mechanism was a highly regulated artefact.

Financial deregulation was a shot in the dark, a response to the volatility of speculation against a fixed exchange rate at a time of extremity, and while those involved have since disputed who deserves credit for making the change, none were sure of its consequences. Initially it brought a resumption of growth and employment by allowing Australian companies to borrow and invest, but the recovery proved short-lived as inflation revived and a surge of imports increased the trade deficit. As the terms of trade deteriorated, foreign debt mounted and the value of the Australian dollar fell. In 1986 Paul Keating warned that if Australia did not deal with its fundamental problems, it would ‘end up being a third-rate economy’, ‘a banana republic’.32

It was now apparent that exposure of the country’s economy to international competitive forces was not enough and that further liberalisation was needed to reduce the rigidities seen as hindering its response. In the course of the 1987 election campaign, Hawke announced ‘the great task of national renewal, reconstruction and revitalisation’; Keating put it more vividly with his explanation that ‘we’ve got to clear all the bloody crap from the pipes’.33 A series of measures followed that were conceived as components of microeconomic reform: the reduction of tariff protection of local industries; the dismantling of price stabilisation schemes in the agricultural sector; the introduction of enterprise bargaining in place of central wage determination; the corporatisation of public enterprises to put transport, communications and utilities on a commercial footing; the promulgation of a competition policy to open them up to alternative providers—and the overhaul of higher education.

All of these measures were justified by the urgent task of national reconstruction, pursued in an atmosphere of crisis. That crisis deepened as a new surge of borrowing allowed a rapid growth of credit, driving up asset prices, encouraging speculation, reigniting inflation and placing new pressure on the balance of payments. These conditions allowed debt-financed takeovers of major companies by reckless entrepreneurs who flaunted their wealth; one of them, Alan Bond, even launched his own university. The government responded by running a budget surplus (Commonwealth outlays fell to just 25.8 per cent of GDP in 1988–89) and lifting the interest rate (it reached 18 per cent by the end of 1989) until the economy crashed into deep recession. This was a hard landing that wiped out some of the country’s biggest businesses, damaged the balance sheets of major banks and destroyed two state banks. Although it finally cured the problem of inflation, the slow recovery from a new post-war peak in unemployment of 11 per cent of the workforce emphasised the cost.

These were the circumstances in which the government embarked on reorganising higher education. As with other components, it did not go uncontested, and some in the Hawke ministry wanted to go further. The Prime Minister himself would have preferred to sell public enterprises rather than commercialise them but was unable to gain Caucus acceptance of such a drastic step, which was finally taken in the 1990s. While Dawkins was able to reorganise the public service in 1984 and impose the management methods of the private sector, it was not until the following decade that the process of contracting out many government activities began.

There were also efforts in the first part of the 1980s to tackle the universities, but only minor changes were possible until the end of the decade. The timing is important. The frontal assault followed the alarmist talk of Australia becoming a banana republic; the Green and White Papers invoked the same idea of a dire emergency; the early years of the Unified National System of higher education had to accommodate tight budgetary constraints and soon a serious recession. As economic policy turned to the supply side with an emphasis on population, participation and productivity, higher education was undoubtedly an important aspect of microeconomic reform, but it was by no means clear how it was to be effected. Control of education belonged strictly to the states, and the universities were self-governing statutory corporations. How then were they to be remade?

Although Australia had both public and private schools, higher education was always a public activity. In 1959, when the Commonwealth began assisting the states to expand their universities and establish new ones, it followed Britain in creating a national body—the AUC—to determine their needs. Unlike Britain’s University Grants Committee, however, the AUC was a statutory agency with broader functions and greater powers. This was partly because the Constitution left education to the states, and it was common to use such expert bodies at a remove from government to distribute federal funds. A further purpose was to safeguard the autonomy of the universities from political interference. The AUC’s role was to plan and coordinate further development, consulting with the universities and the states before it published a detailed report every three years setting out its advice to the Commonwealth on provision for the coming triennium.34

The growth of Commonwealth support brought greater complexity to these arrangements. When it extended assistance to the colleges, which had been administered by the states, they needed their own bodies to deal with the Commonwealth’s Advisory Committee on Advanced Education (which in 1971 became the Australian Commission on Advanced Education, on the same basis as the AUC). Except in Queensland, the new state bodies (variously designated a post-secondary education commission, higher education board or tertiary education authority) embraced the whole of higher education—for even though the universities were autonomous organisations that negotiated directly with the AUC, the funding formula still required the state treasury to match the Commonwealth grant. That brake was released when the Commonwealth assumed full financial responsibility for both universities and colleges in 1974, leaving a vexatious separation of functions: higher education was completely funded by one level of government but legally controlled by another.35

The arrangements for research were more fragmented. Australia relied heavily on public funding of research since foreign corporations controlled the majority of enterprises using advanced technology, and much of this public research was conducted in government agencies such as the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). The AUC’s triennial grants to universities included a research component, part of which was used for the purchase of equipment and library materials and part distributed to academic departments. To meet the cost of major projects there were two funding agencies, an Australian Research Grants Committee (formed as a result of the Martin report) and an earlier and separate National Health and Medical Research Council. But these were located in two other Commonwealth departments, Science and Health, at a remove from the Department of Education and the AUC.

The Fraser government sought greater cohesion in 1977 by consolidating the three advisory bodies for universities, colleges and TAFE into a single agency, the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission (CTEC). In doing so, however, it maintained three councils, each on a statutory footing with dedicated staff, part-time members and a full-time chair. Apart from its own chair, CTEC was made up of the three council chairs and five part-time members drawn largely from the sector. The councils provided separate advice to the Commission, which published them along with its own funding guidelines for each triennium. After receiving advice from the Commonwealth, it then considered the detailed submissions of the universities and the states before making final decisions. But by this time the Federal Government was setting limits of expenditure in advance and issuing CTEC with specific policy directives.

That such a cumbersome structure retained credibility was largely due to the head of the Commission, Peter Karmel. A member of the Martin committee, the founding Vice-Chancellor of Flinders University and architect of the Schools Commission, he had an unsurpassed knowledge of the whole field of education. An economist with particular expertise in demography, he appreciated the value of projecting student demand and workforce requirements, conscious of the fallibility of such predictions and ever mindful that universities were more than training institutions:

In a free society universities are not expected to bend all their energies towards meeting so-called national objectives which, if not those of a monolithic society, are usually themselves ill-defined or subject to controversy and change. One of the roles of a university in a free society is to be the conscience and critic of that society; such a role cannot be fulfilled if the university is to be an arm of government policy.36

Karmel was a man of incisive intelligence and natural authority who enjoyed the confidence of successive governments: the Coalition appointed him to chair the AUC in 1971; he distributed the largesse provided by Whitlam and retained the chair when the Fraser government created CTEC. Karmel was a principled pragmatist, aware of the need to accommodate changing government priorities, able to ‘interpret them in a way that enables institutions to function as well as possible’.37 His relations with the sector were also good, for he understood how it worked and sympathised with its aspirations. With a staff of around a hundred officers, CTEC had an intimate knowledge of each institution. Even if it was not able to provide the money a university sought, the reason was explained fully and publicly.

The task of a buffer body reconciling the needs of institutions and the imperatives of government became much more difficult in the 1980s. When Karmel left CTEC to become Vice-Chancellor of ANU in 1982, the chair of the TAFE Council filled in until the new Labor government found a successor two years later. This was Hugh Hudson, an economist who had been a member of Karmel’s department at the University of Adelaide before going into state politics, where he served as minister for education in Don Dunstan’s Labor government and was deputy premier before losing his seat in 1979. Hudson was close to his minister, Susan Ryan, and a pugnacious defender of CTEC’s prerogatives as the body that determined higher education policy. But other Commonwealth departments had come to see the buffer body as too close to the sector it was meant to direct and an obstacle to the changes they thought necessary.

The founding compact between the Commonwealth and the universities rested on the assumption that mutual good will would harmonise national objectives and institutional autonomy. The university could not fulfil its unique function in the absence of a broad freedom to conduct its own affairs, so the government would limit the use of its financial power and refrain from interference. In return, the Murray committee expected universities to serve the Australian community and ‘keep clearly before their minds the considerations in regard to the national interests which are bound to weight with governments’.38

No regulatory body could ensure the good will and cooperation necessary for such a compact to work. It was strained by the expansion from universities to an enlarged sector of higher education—the colleges were never accorded the same freedom of action enjoyed by the universities—and its mounting cost. The decision of the Commonwealth to abolish fees from 1974 and take full responsibility for the sector was an augury of how it would invoke its financial power, for the Whitlam government forced the states to scrap university fees by making this a condition of their grants. Moreover, higher education became completely dependent on federal revenue just as it dried up. The AUC had coordinated the growth of the nation’s universities; CTEC could only try to soften the effect of the government’s economy measures on a supplicant sector.

Even though higher education was in a steady state, the pressures on it were building. One was demand. Youth unemployment remained high throughout the 1980s as low-skilled jobs that had been available to early school-leavers disappeared: the number of teenagers in full-time work fell from 512 000 in 1980 to 390 000 by the end of the decade and would fall further as the result of the recession in the early 1990s. Since eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds held the great majority of these jobs, there was a determined effort to keep younger Australians in the classroom. Hence the Labor government’s Participation and Equity Program, which provided support to schools with low retention rates, along with changes to curriculum and assessment and financial assistance to students from low-income families. Just 36 per cent of students stayed on to Year 12 in 1982. That number rose to 53 per cent in 1987 and reached 77 per cent by 1992. Continuation to further study increased at a lower rate, but was sufficient to lift higher education admission requirements appreciably during the 1980s.39

Older students added to the demand. Whitlam’s abolition of tertiary fees and provision of income support opened the door to many who had been denied the chance to go from school to university, especially women who relished the opportunity to pursue intellectual interests. These ‘mature age’ students, as they became known, brought a life experience and curiosity to their studies, and many chose courses in Arts faculties. In the 1980s there was greater demand from those already in the workforce for qualifications that would improve their career prospects as the labour market turned against manufacturing, clerical and other declining occupations. TAFE was the most accessible, but the number of students in higher education over the age of thirty also rose from 85 000 at the beginning of the 1980s to nearly 150 000 at the end of the decade. Universities introduced new methods of selection for such applicants, but these came at the expense of qualified school-leavers. By the mid-1980s, more than 10 000 of them were unable to find a place.40

Committed to budgetary restraint, the Hawke government was unable to provide more than a modest increase in student places. It did so at a reduced rate of funding in the expectation that this would force the sector to operate more efficiently—there was much talk of laxity in staffing arrangements and the under-utilisation of facilities on campuses that remained idle for a large part of the year. Members of the Cabinet saw universities especially as places of social as well as financial privilege, a drain on the public purse that needed to be reduced. There was already talk of charging fees.

European countries had a long tradition of free university education. Australia came to it late after a protracted elimination of fees. Many students had attended university free of charge since the introduction of Commonwealth scholarships after World War II, and many more benefited from pre-employment contracts and stipends offered by the state education departments and the private sector. In 1973, when the Whitlam government announced the abolition of fees, only a fifth of full-time higher education students were paying them and at a rate that represented just 15 per cent of the cost of tuition.41 The Fraser government tried to reintroduce fees for second and advanced degrees when it came to office and again in 1981, but retreated on both occasions in the face of student protest. Although a recent arrangement, free higher education was already seen as emblematic of a civilised citizenry, and enjoyed strong public support.

During 1984 Bob Hawke sat down with the country’s vice-chancellors and asked them for their views on charging tuition fees. After nine raised their hands to indicate support and ten signalled their opposition, the Prime Minister told them, ‘That was very interesting.’42 Early in the following year Dawkins’ friend Peter Walsh, who had succeeded him as Minister for Finance, circulated a paper proposing an annual fee of $1500 on the grounds that university students still came overwhelmingly from wealthy families. He and other members of the Expenditure Review Committee preparing the 1985 budget pressed this proposal on Susan Ryan, although her appeal to the Caucus education committee and a concern for the political sensitivities of such an abrupt change to Labor policy headed it off.43 Instead the government introduced a $250 administration charge in the 1986 budget. There was strident student protest, and universities complained that they were expected to collect the payment even though 90 per cent of it was remitted to Canberra (administrative staff objected particularly to the name on the grounds that it would prejudice students against them). Several universities had to change their statutes to levy the Higher Education Administration Charge, but were forced to do so since the Hawke government followed the precedent set by Whitlam and made compliance a condition of its funding.44

It had already identified another source of fee income. Since World War II, Australia had offered education and training to students from South and South-East Asia; many were sponsored under aid programs, although by the 1960s most paid the same fee as Australian students until 1974 when they too enjoyed free tuition. Because an increasing number of such students failed to return to their country of origin, the Fraser government tightened rules of entry and introduced an overseas student charge set at about a quarter the cost of the course. When Labor took office in 1983, it undertook a review of the overseas aid program, which recommended greater realism, transparency and self-interest. Other OECD countries were actively recruiting international students, and after the Thatcher government required British universities to charge full-cost fees, such students provided a significant source of university revenue. Accordingly, the review advised that it would be better to replace the current mix of sponsored and subsidised places and treat education as an export industry, charging full fees and with an increased number of scholarships for deserving cases.45

Anticipating such a finding, Susan Ryan commissioned her own review of arrangements for the non-sponsored international students, which warned against such an abrupt reversal of policy and recommended a gradual increase in charges. Nevertheless, the government decided in 1985 to develop marketing of full-fee international education as an export industry and gave universities strong incentives to participate. There would be no limit on numbers, they would retain most of the revenue and fees were set well above cost. The new policy was determined by the economic ministers, the initial overseas promotion undertaken by Dawkins’ new trade agency.46

If higher education could be an export industry, would it support private providers? Australia had no equivalent to the US private universities, which drew on that country’s strong tradition of philanthropy and were not conducted on commercial lines. Here a weaker tradition had worked to the benefit of the older public universities, but they attracted very few benefactions after the Commonwealth assumed financial responsibility for them. The churches directed their principal educational effort to the provision of schools and were kept at arm’s length from the secular universities, although the principal denominations maintained affiliated residential colleges. There were separate teacher training colleges for the Catholic sector, but these were supported on the same basis as other CAEs. The sudden impulse to create private universities did not arise within the sector but from outside and with the clear intention of profit.

After Alan Bond persuaded a Japanese company to buy a tract of sand hills he owned north of Perth—he had painted them green to attract investors—it sought to revive interest in the grandiose scheme of a Yanchep Sun City by proposing it include a campus for overseas students. This initiative, which depended on government assistance and collaboration with an existing university, was abandoned, but Bond himself proposed a similar arrangement on the Gold Coast in partnership with another Japanese company and secured assistance as well as legislation from the Queensland government for the creation of Bond University in 1987. In both cases the commercial viability of the university rested on an appreciation of the value of real estate held by the parent company. Another such venture was initiated by a pastoral company that launched the Cape Byron International Academy, to be built at Byron Bay on the north coast of New South Wales with teaching provided by a nearby CAE. It lapsed when the promoters attracted the interest of the state’s corruption watchdog. More orthodox proposals also struggled. Michael Porter, a free-market economist, sought corporate backers for a Tasman Institute that would conduct a business school in Melbourne but its potential patrons preferred to direct their funds to the Graduate School of Management established at this time at the University of Melbourne.47

Susan Ryan was flatly opposed to private universities, but other ministers were not. Alan Bond, still basking in the glory of winning the America’s Cup for Australia, made strong representations to Bob Hawke, who in turn made clear his displeasure with the Minister for Education’s obstruction. Hugh Hudson had won no friends by his appearances alongside his minister before the Expenditure Review Committee, and his public advocacy of increased funding brought a shot across the bows of CTEC: the Cabinet instructed it in August 1985 to conduct a comprehensive review of the sector’s efficiency and effectiveness. The committee that conducted the review included representatives of the colleges and universities, so Peter Karmel was able to assist Hudson in preparing the report. In making recommendations for improved management, better use of facilities, more flexible staffing arrangements and closer direction of research, it presented clear evidence that higher education had already found most of the efficiency gains that were available during the steady state and that there was little scope for additional savings.48

The government was pleased with CTEC’s recommendations for greater efficiency and effectiveness and instructed it to implement them forthwith; Dawkins would take many into his own plan for higher education. There was less confidence that the report went far enough. Treasury and the Department of Finance thought CTEC should have investigated alternatives to the block funding of institutions that would allow greater direction and accountability (the committee had examined and rejected their proposals). The Department of Science and the government’s principal advisory body, the Australian Science and Technology Council (ASTEC) had their own views on research policy; the Department of Employment and Industrial Relations wanted changes to staff practices, and the Department of Industry, Technology and Commerce urged a broader, independent review.49

The government’s interest in the sector did not end there. The office of the Economic Planning Advisory Council, a forum of business, unions, state governments and other parties created to carry forward the work of the Summit, turned its attention in 1986 to the country’s poor productivity performance. It found that Australia lagged more successful countries in workforce skills and argued that the education and training system had to become more flexible and responsive to the needs of industry.50 A similar message came in 1987 from Australia Reconstructed, a joint report of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and Trade Development Council commissioned by John Dawkins. It too called for a broadening and deepening of skills throughout the education system, with greater emphasis on technological and business courses.51 These reports were principally concerned with the TAFE sector, although both insisted that universities and colleges must play their part. There were signs that a binary system would be drawn into a trinary system of post-secondary education.

By this time it was difficult to distinguish the two branches of higher education by the scope of their activities: medicine, dentistry and veterinary science were the only university courses not taught by a college, the larger institutes of technology were conducting significant research, and several CAEs were offering doctoral programs. The CTEC report accepted the need for some relaxation of the binary divide. Where larger institutes of technology had appropriate facilities, they should be offered assistance for applied research, and where they were able to offer doctoral programs of an appropriate standard that were not available in a nearby university, they should be allowed to do so.

These concessions offended the universities without satisfying the colleges, for CTEC insisted that the dual funding arrangements—universities supported for teaching and research, colleges for teaching only—must continue. It also issued a general rebuke to institutions on either side of the divide for a preoccupation with status and resources at the expense of their educational missions, and expressed particular criticism of a proposal in Western Australia to elevate its institute of technology into a university, although CTEC was unable to prevent the state parliament from effecting that change unilaterally in December 1986. The AVCC condemned the usurpation of status: ‘The notion that a college of advanced education could be transformed into a “university of technology” by a stroke of the legislative pen is illusory.’ But within eighteen months the AVCC felt it necessary to admit the Curtin University of Technology to membership. With several other institutes of technology seeking to elevate their status, the binary divide was breaking down.52

So too was CTEC’s standing as an authoritative adviser on higher education. As the powerful coordinating departments of Treasury, Finance, and Prime Minister and Cabinet found it unresponsive to their desire for change, they looked to alternative sources of advice. In 1985 the Cabinet asked the scientific advisory body ASTEC to report on how to improve the research performance of higher education. Its report to the Prime Minister in the following year sounded the appropriate notes: the sector had an important role to play in alleviating the country’s economic problems by an improvement of the technological base, but only if the research effort was reorganised. Australia relied too heavily on publicly funded research, and too much of it was distributed to universities as part of their recurrent grant, where it was spread too thin. The direct support for research provided by the Australian Research Grants Committee (ARGC) was inadequate and undirected. A new Australian Research Council (ARC) was needed with additional funds and the power to set priorities, build industrial links and ensure greater concentration of effort.53

It was particularly unfortunate that the ASTEC report coincided with a public attack on the ARGC’s allocation of funds for research projects. The Coalition had established a Waste Watch Committee, which examined a list of successful applications for grants and in March 1987 pronounced more than sixty to be an esoteric misuse of public money. ‘Motherhood in Ancient Rome’ was the project singled out for greatest derision, although ‘Syntax in Jane Austen’s Novels’ and ‘Techniques of 17th Century Dutch Shipbuilding’ ran it close. Stung by an onslaught of mockery and indignation on talkback radio, the Cabinet cut the ARGC’s appropriation, which already trailed behind that of the National Health and Medical Research Council. ASTEC’s recommendation that research should be relevant to ‘important economic or social issues’ could hardly have been more timely.54

If Hugh Hudson was affronted by ‘ASTEC’s latest incursion into education policy’, then the government’s response to its report exacerbated his ire. Dawkins took a submission to Cabinet within a month of becoming Minister for Education, which proposed that the ARC be located in his department rather than Science. It would not be a statutory agency, as ASTEC proposed, nor part of CTEC, for he intended it to override that agency’s direction of higher education research. In the meantime money would be transferred from CTEC for the ARC to administer the new research centres and support for applied research in the institutes of technology that the Commission had recommended.55

All Cabinet submissions were required to include advice on the political sensitivity of the decisions they proposed. Dawkins acknowledged that there would be criticism of the failure to allocate the additional funding ASTEC had recommended and possibly the refusal to make the ARC a statutory agency. Untroubled by the warning and comforted by the support provided by all interested departments except Barry Jones’ Science, Cabinet accepted Dawkins’ proposal. The protests of the universities and those who worked in them were by this time a matter of course and little moment.

Among the universities there was growing recognition that the ground had shifted and that there would be no return to the halcyon days when they were allowed to determine their lines of growth. The more prescient university leaders were aware that theirs was not a unique fall from grace. In 1985 the AVCC held a lengthy forum on the changed expectations of higher education. Peter Karmel explained that the CTEC review of efficiency and effectiveness was the result of a wider and more ‘general scepticism about the efficiency of all educational institutions’, so that governments were no longer responsive to pleas for additional support. The language of public policy had shifted from ‘input to output considerations’, and ‘unless universities can provide uniform, measurable sets of objectives they will be targets for political destruction’.56

Discussion then turned to a recent British report on measures to improve the efficiency of university management. This had been commissioned jointly by the AVCC’s counterpart and the University Grants Committee in response to funding cuts that were much deeper than those in Australia, and it proposed stronger executive control, program budgeting, clear lines of accountability and performance management. John Ward, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney, observed that the ‘managerial assumptions’ of the report had aroused ‘anger and dismay’ in British academic circles, and so they had for these unpalatable measures were designed to restore confidence that the universities could make better use of public funds. But that did not protect them from further cuts in subsequent years or save the University Grants Committee from termination.57

It was the same in other countries. In the 1960s and early 1970s they too had built large and diversified systems of higher education, that term embracing various configurations of universities, institutes and colleges of technology. Enrolments, staff numbers and government expenditure doubled, and in some cases trebled or even quadrupled in the space of fifteen years. Higher education was expected to do more things, train more people for more occupations and produce more knowledge for more purposes.58 Just as this prodigious expansion faltered, the American sociologist Martin Trow offered an influential explanation of its effects. When higher education grew to incorporate more than 15 per cent of an age cohort (as it had in Australia during the 1980s), the quantitative increase brought a qualitative change in its nature, structure and outcome. A restricted system that prepared a small, privileged group for their elite roles became a mass system training a larger, more heterogeneous student body for a variety of occupations.59

The impetus for a mass system was greater participation, both to increase work skills and productivity and to promote social mobility. It required universities to revise their academic mission, broaden their selection of students and provide them with new forms of support, pay greater attention to the management of teaching and research, and be more responsive to patterns of demand. Their implementation of these changes was prolonged and difficult, but it was made much more painful when sustained prosperity gave way to endemic stagflation. It was not just that the reversal in the fortunes of these countries with advanced economies called into question the belief that investment in human capital would propel them on a path of prosperity. Beyond this, budgetary austerity brought a reduction in outlays on education. An international survey published in 1987 found that universities everywhere were under intense scrutiny:

Universities in OECD countries today confront common problems which derive from a single central fact: they are being called upon to play an ever more important part in the restructuring and growth of increasingly knowledge-based national economies, at the same time as they are under pressure from cuts in public spending, demographic downturn, diminished legitimacy and the consequences of rapid growth.60

There was also a growing conviction that higher education institutions could not cope with this pressure without external intervention, that they needed greater direction, stronger management and clear accountability if they were to play their part. The Australian universities and the agency responsible for them had so far resisted such intrusion, but the patience of the interventionists was wearing thin. The reckoning would be sudden and severe.