The Soviets preferred large cordon and search operations to deal with large zones of Mujahideen-dominated territory. They would cordon off the area using dominant terrain, roads and rivers as boundaries. Then they would push forces through the area looking for weapons, stores and Mujahideen. The Soviets often used DRA forces to do the actual searching. The DRA usually combined taxation and press-gang conscription with the search. At first, the Mujahideen were vulnerable to these large-scale operations but then they learned to build fortifications throughout the zones, coordinate their defense, constitute a reserve and exact a toll on the searchers.

Baraki Barak District is a very fertile oasis and a major green zone located between the two main highways running south and southwest from Kabul. One highway runs from Kabul to Gardez in Paktia Province and the other runs from Kabul to Gazhni and on to Kandahar. The waters of the Wardak River and Wardak Gorge irrigate this fertile area and wheat, corn, and rice fields intersperse with vineyards and orchards. This fertile, well-populated valley provided a natural base from which the Mujahideen could attack both of these main LOCS as well at Muhammad Agha District to the north and Gardez in the south.

In June 1982 there were several Mujahideen bases located in the Baraki Barak District. We had brought a number of heavy antiaircraft machine guns into the area, particularly the ZGU-1 14.5mm single-barreled machine gun. The enemy was concerned about the presence of these air defense weapons. We received information that the enemy was preparing an offensive into our area with three major objectives: first, to seize our air defense weapons that were becoming a hindrance to their air raids in our AO; second, to capture some of the leading Mujahideen commanders who continuously harassed and attacked Soviet and DRA columns traveling on the two highways which bordered our area; and, third, to seize control of the area and restore the district government to the DRA. We had overthrown the DRA district government in 1979.

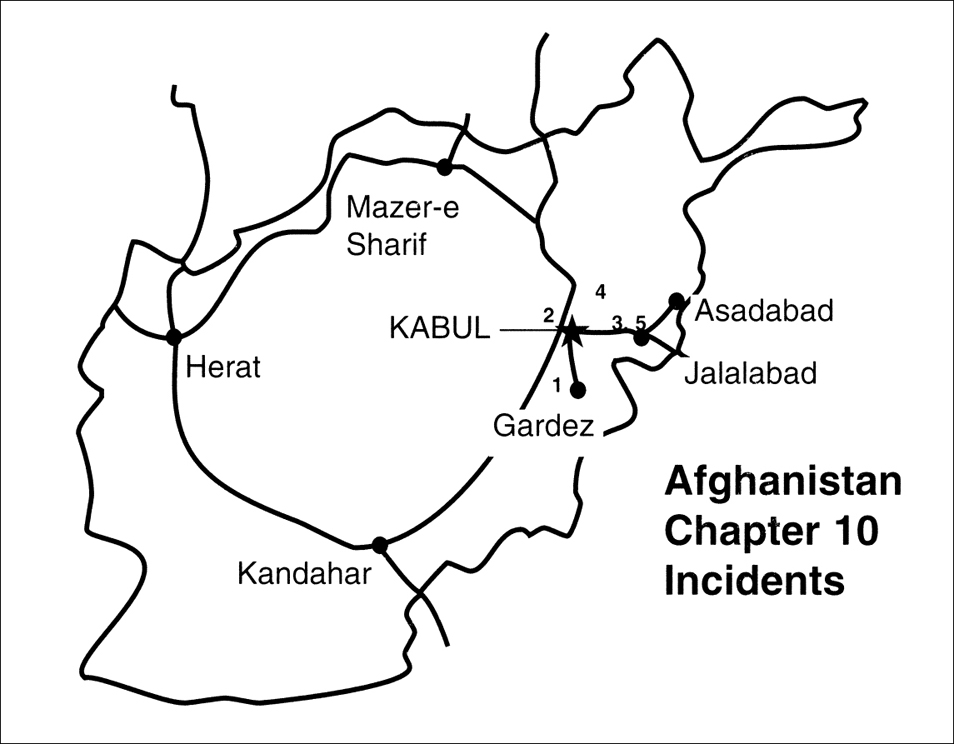

The Soviets and DRA launched their offensive with more than 20,000 troops involved directly and in support (Map 10-1 - Barak). They sent out three columns, one each from Gardez, Kabul and Wardak.1 These forces moved to our area, established a cordon around it, occupied the high ground and began attacking some of the Mujahideen positions. The column from Kabul occupied Pul-e Alam and from there sent one detachment to the. west around Mir Abdal mountain to flank the district from the northwest. The column from Gardez moved west of the road to the Altamur plain and covered the southeastern axis to the district. The column from Wardak occupied positions on the district’s western flank. The enemy blocked practically all major axes out of the area. Since we Mujahideen commanders knew of the upcoming offensive, we had gathered earlier to draw up a joint defensive plan. All faction commanders participated and we constituted the southeastern and northwestern defensive sectors and assigned defensive areas within these sectors to different factions and units. We organized our forces into small groups to insure our ability to maneuver and then occupied positions in the perimeter villages of our district. We constituted mobile interior reserves and kept them available to react to enemy actions.

I commanded the southeastern sector. I had approximately 800 Mujahideen, armed and unarmed, under my command. Our weapons included ZGU-1s, DShKs, many RPG-7s, PK machine guns, 82mm mortars, 82mm and 75mm recoilless rifles, machine guns, and a number of .303 bolt-action Enfield rifles. These Enfields were quite effective against dismounted Soviets. They had a maximum effective range of 800 meters compared to 400 meters for the AK assault rifle. Further, the more-powerful .303 round would penetrate Soviet flak jackets while the AK round would not.

The enemy deployed his artillery on the Altamur plain and at Pul-e Alam. His column from Wardak occupied the line Dashte Delawar—Cheltan hill—and the northern villages to the high ground. The enemy initiated their attack with heavy artillery fire and air strikes on the villages and suspected Mujahideen positions. The artillery fire continued for several hours. They hit the positions of the ZGU-1s and set the entire area on fire. The enemy advanced from the southwest between Cheltan and the road and entered our villages and searched them. They also attacked from the other directions against the perimeter villages that they were facing. Our Mujahideen fought them from their forward positions and fell back to back-up positions as the enemy entered the villages. The villages and orchard provided good cover and concealment and, although the enemy had the area surrounded, we were able to move freely within the 10-kilometer-wide area. We began to launch small-group counterattacks with our scattered groups of Mujahideen. We hit the enemy from many directions.

We suffered casualties, but the enemy also got a bloody nose. It was an infantry fight at close quarters. Three Mujahideen in my immediate group were killed during our local counterattack. Soviet forces were encircled and the Soviets launched counter-counterattacks to aid their encircled forces. We also reinforced our forces. Our forces were intermingled and the Soviet artillery was unable to fire into the area of contact for fear of hitting their own troops. Fighting continued until dusk. As night fell, fighting slackened and stopped.

The next morning, the enemy resumed the attack, but this time from the east using tanks and infantry. We Mujahideen had mined the Khalifa Saheb Ziarat2 approach. The Soviets brought dogs to detect the mines. My group in this area were in well-covered positions with three RPGs. As the enemy cleared the minefield and moved forward, we opened fire with our RPGs on their tanks standing in the open cultivated areas. The enemy responded by moving overwhelming force into the area. The Mujahideen responded by moving out of their positions to move through gaps to attack the enemy on the flanks. Small groups of Mujahideen with RPGs also maneuvered through the concealing terrain folds to engage the enemy. This totally changed the situation, with the enemy stopping and going to ground in defensive pockets. The enemy’s momentum was lost as his attack bogged down. The Soviets occupied villages, farm buildings and orchards and turned them into defensive positions as the second night fell. The Soviets were scattered in five or six pockets and the Mujahideen kept them from linking up. We Mujahideen knew the terrain and the local civilians helped us move from position to position. We attacked the Soviets from all sides, but suffered casualties as well. For the next day and night, the situation continued. Both sides were intermingled and the whole area was on fire. We saw guns capable of firing in every direction (D30) and saw a single-barreled grenade launcher (RPG-18). This was the first time we captured AK-74 assault rifles.3 Flak jackets protected the Soviets from AK fire, but our old .303s penetrated them. After three days and nights, the enemy began to withdraw. Every column returned by the direction it had come.

None of the enemy’s three objectives were achieved, but our losses were very heavy with about 250 KIA. The enemy spread rumors that they killed more than 2,000 of us. I don’t know what the enemy losses were, but we saw blood trails and blood pools all over the former enemy positions. The enemy had done very hateful things in the villages they occupied. They defecated in the crockery, smashed pots and furniture, and destroyed villagers’ food by cutting open sacks of wheat, flour, salt and sugar and pouring it out on the ground. They also pulled down walls, broke doors and ruined houses.

COMMENTARY: The Soviets and DRA throughly planned this operation. The converging movement of three columns from three directions was a desirable operational maneuver since it left the initiative in the Soviets’ hands and kept the Mujahideen off balance. However, once the Soviet/DRA force entered the green zone, the terrain and Mujahideen active defense split the communist force into a series of isolated pockets which the Mujahideen were able to contain. The Soviet/DRA force lost the momentum of the attack and were unable to regain it. The initiative passed to the Mujahideen.

The Mujahideen planned their defense throughly. They conducted an active defense which incorporated tactical maneuver. They maintained a central reserve and had the advantage of interior lines. Terrain, well-constructed field fortifications and an aggressive defense enabled the Mujahideen to split the Soviet/DRA forces into isolated groups and stop their advance.

The Soviets and DRA did little to win the hearts and minds of the populace outside of the areas they controlled. On the other hand, Mujahideen activity often endangered the lives and property of the populace. During the course of the war, the Soviets never controlled Baraki Barak, but they bombed and shelled it continually. Farming was disrupted and most of the population migrated to Pakistan or the cities.

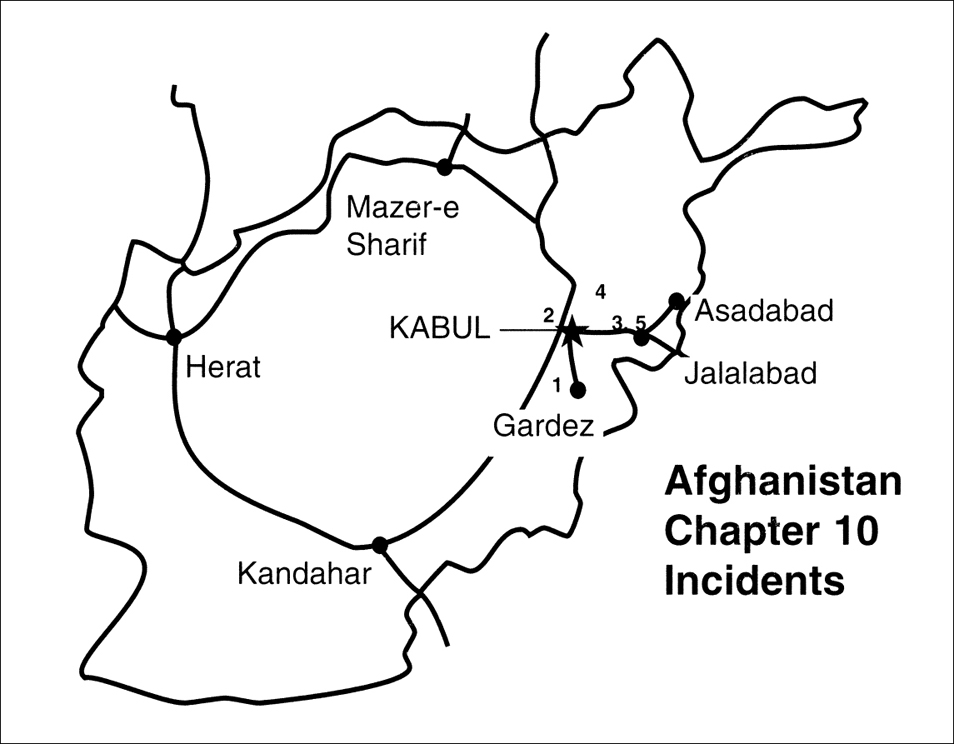

In August 1982, the Soviet/DRA forces launched a search and destroy operation against Mujahideen bases in Paghman. There were two enemy columns. The main column moved southwest from Kabul and then turned northwest onto the main highway to Paghman. Its mission was to destroy resistance bases in the center, south and southwest of the Paghman area. The other, smaller column moved north from Kabul and then turned northwest. Its mission was to block Mujahideen escape routes along the northeastern edge of Paghman through Ghaza and Zarshakh villages (Map 10-2 - Ghaza).4

Initially, the movement of the two columns in opposite directions deceived the Mujahideen as to their enemy’s real intention. Nevertheless, when the Mujahideen saw the main column heading toward the city of Paghman and its western and southern suburbs, they quickly occupied prepared defensive positions and readied themselves for battle. However, the Mujahideen lost track of the northernmost column. It came through the town of Karez-e Mir and moved undetected to take up positions on the hills between Somochak and Ghaza. From the hill positions, the enemy column commanded the main road from Paghman to the Shamali plain north of Kabul.

The next morning I dispatched two escorts to take one of my wounded Mujahideen to Shamali for treatment. As they moved through the Somochak Valley, they were ambushed and the escorts were killed. The local Mujahideen from Somochak village went to investigate and discovered that Soviet troops had occupied the ridge overlooking the village. The Somochak Mujahideen attacked the ridge, but the Soviets were too strong to be overrun. Other Mujahideen in the area began to discover the enemy presence. Mujahideen in the village bases of Qala-e Hakim and Isakhel and in the valley base of Dara-e Zargar joined together. I took some 30 or 40 Mujahideen onto the high ground at Loy Baghal Ghar. The Somochak Mujahideen reinforced their positions near the village. The Zarshakh and Ghaza Mujahideen moved to cut the LOC of the Soviet force east of the Torghonday hills. We had encircled the Soviet force in the northeast sector with about 100 Mujahideen.

The fighting went on against the DRA/Soviet forces throughout Paghman. We kept the northern Soviet blocking force pinned down, exchanging fire with the Soviet troops for two nights and three days. We commanders met and decided to attack and eliminate the Soviet force on the afternoon of the third day. We launched the attack from the west while the eastern Mujahideen contained the enemy. Our progress was slow, however, since we did not have enough support weapons. We had Kalashnikovs, .303 Enfields, a few RPG-7s and some 60mm mortars with a small stock of ammunition. We needed heavy machine guns, 82mm mortars and rockets. As we Mujahideen were closing to the Soviet positions, some 14 Soviet helicopters, including gunships, arrived over the battlefield and began gun runs against us. We sustained heavy casualties and broke off the attack. The transport helicopters landed and began lifting off the Soviet troops and flew them away to Kabul. We had won the fight, but we suffered 23 KIA and many others WIA in the three-day battle.

COMMENTARY: The Soviet/DRA force did an effective job initially in disguising their objective and managing to move their northern column while eluding Mujahideen surveillance. The northern column effectively performed a surprise approach march and quietly occupied necessary terrain. The northern column was organized to block Mujahideen escape routes and so was lightly equipped. It was battalion-sized or smaller. It seized and occupied its initial position, but made no effort to expand that position so that it could achieve its objective of completely blocking Mujahideen escape routes. Further, once it disclosed its presence by firing on the litter party, it made no attempt to seize the initiative, but remained passively in the defense. Coordination between the northern column and the main column was lacking since the main column seemed unable or uninterested in aiding the northern column despite their close proximity.

The Mujahideen reaction was excellent. They quickly took up positions on commanding high ground overlooking the Soviet positions and sealed the area, trapping the Soviet force. However, the Mujahideen lacked long-range heavy weapons, so they could not exploit the advantage that their dominant terrain gave them. The Soviets were in range of the bulk of Mujahideen weapons only during the Mujahideen assault. The Soviet helicopter strike effectively countered this assault. Soviet helicopter gunships were not as effective at night. Perhaps the Mujahideen assault would have had a better chance if the attack were launched at dusk or before dawn.

Mujahideen use of battlefield maneuver was commendable. They offset much of their disadvantage in fire power, took dominant terrain and attack positions, seized the initiative from the Soviets by trapping them and forced the Soviets to stage a rescue by hazarding helicopters. All of this was due to effective Mujahideen maneuver. If the Mujahideen had some anti-aircraft weapons, they could have bloodied the Soviet force badly. As it was, Mujahideen maneuver prevented the success of the Soviet/DRA offensive and decided the outcome of the battle in the Mujahideen’s favor.

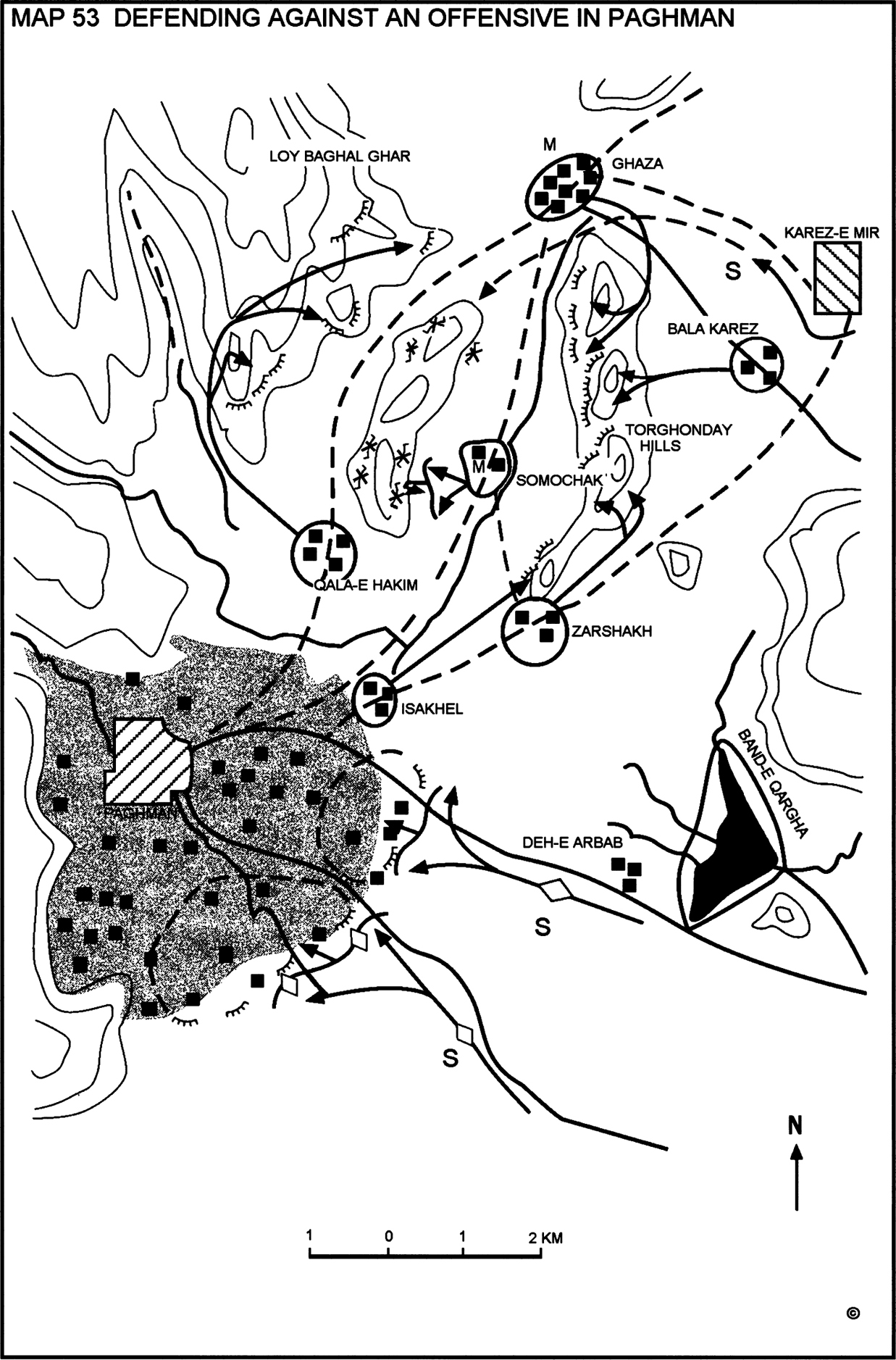

The Kama area, located northeast of Jalalabad, is approximately 87 square kilometers in area. It is bordered in the west by the Kunar River, in the south by the Kabul River and in the north and east by mountains. It is a large, well-irrigated green zone which was densely populated before the war. The Mujahideen in the area were all locals defending their home turf. In February 1983,1 commanded a group of 35 men in my village of Sama Garay (one kilometer east of the town of Kama). We had Enfield and G35 bolt-action rifles and a few Kalashnikovs. We lacked the capability to launch major attacks, but conducted hit and run actions. We did not have a base in the mountains, but lived in the village. There were similar units in the other villages in the area. The Kama District Mujahideen were very fragmented and we had no contact with many groups in the area and so we couldn’t help each other. The Soviets could deal with us piecemeal. We Mujahideen did not have a common contingency plan to deal with the Soviets when they came in force to kill us all. And even if we had such a plan, at that time our communications were primitive and most communications were done with messengers.

The Soviets were close at hand. The Soviet “Thunder” unit6 was stationed in Samarkhel to the east of Jalalabad. They crossed the Kunar River and established a base south of the Tirana Ghashe on the plain (Map 10-3 - Kama). Then at dawn on 15 February 1983, 20 to 25 of their helicopters landed troops in the mountains north and northeast of Kama. The helicopters landed at Mashingan Ghar, Spinki Ghar, Dergi Ghar, Wut Ghar, Cokay Baba Ghar, Kacay Ghar, and Tirana Ghashe. The troops on the high ground sealed off our escape into the mountains. At the same time, a detachment from the Soviet base at Samarkhel crossed the Kabul River to establish the southern part of the cordon. The main Soviet ground sweep started from Tirana Ghar moving to the east.

We woke up to the sounds of helicopters and the lights of flares. We were facing a large force—possibly bigger than a regiment. I was saying my morning prayers when my guard approached and said “Commander, things look different this morning.” I told him, “Don’t worry, our lives are in the hand of God, not the Russians. We are destined to die on the day that is destined for us. It will not be pushed backward or forward.” The helicopters continued to fly over, wave after wave.

I saw a group of Mujahideen from the village of Mastali running away between Wut Ghar and Dergi Ghar. As they moved along the road, the Soviets on the high ground began shooting at them. I saw two of them go down. Gulrang was one and the son of Ghulam Sarwar the driver, was the other. Both were killed. The rest escaped into the mountains.

We were close to the river, so we moved to the south of Kama where there is a bushy area and a mosque. We took refuge and hid ourselves there. Everything was quiet in our area for hours. My Mujahideen came to me and asked what was happening. It was now 1100 hours. I said that the Russians would come when they would come, but we were hungry now. I approached a village for food. Someone came out and told me not leave the hideout since enemy tanks were five minutes from the village. I returned to the hideout. Around 1400 hours, another villager came and told me to leave the bushy area since the Russians were going to set it on fire to flush us out. He said eight tanks and APCs were approaching the area. We moved to the edge of the wooded area where there is a natural berm and took up positions there. We had one RPG-7 with three rounds, two Kalashnikovs, and some Marko Chinese bolt-action rifles.7 The wooded area was also full of civilians who were hiding from the Soviets, so we felt an obligation to defend them and the wooded area and prevent the Soviets from setting it on fire. I saw BMPs moving toward us. They stopped short of and bypassed the wooded area and turned toward Kama. It was now 1500 hours. When we were scattered throughout the wooded area, I received a message from the rest of my men who described their location and asked me to join them since the air assault troops were moving to Mashingan village. I took my 12 men with me and we moved to join the rest of my men. The Tawdo Obo highway bridge was close to our village. I joined the rest of my men at that bridge which was near the village. We decided that the Soviets coming from the high ground would cross over this bridge, so we took positions on both sides of the road leading to this bridge. As we were taking our positions, a group of Soviets moving toward us opened fire on us.

A bullet hit the butt of the rifle of my cousin, the son of my maternal uncle, and smashed it. “What will I do now?” he asked. “I will find you another,” I stated. As I approached the road, I saw my friend Habib Noor some 30 meters to my right shooting at something. I hit the ground and saw that he was shooting at two Soviets. He killed them both. “Get their Kalashnikovs, Commander” he yelled at me. I sprinted across the road and grabbed a Kalashnikov, but the rifle’s carrying strap was around the corpse’s body and I couldn’t get it loose. I saw a lot of Soviets coming at me and they were all firing (they put ten bullet holes through my baggy trousers). Bullets were flying all around me. I kept tugging, but the rifles wouldn’t budge, so I abandoned trying to get the Kalashnikovs. I had an RPK-3 antitank hand grenade. I wanted to use it, even though there was no tank, to make some noise to distract their attention so I could get away. I threw the grenade. After four seconds, it exploded and made a big noise and I got away to where my friend Habib Noor was. Habib Noor told me that, unless we crossed the stream to the north, we would not be able to engage the Soviets. He told me that since I am short and he is tall, I had a better chance of making it across unobserved and I should cross. I told him “I am your commander, but I am under your command now.” I ran across and jumped but landed directly into the stream. “Oh Allah,” I cried “you have killed me without dignity.” Then I made a big jump, I don’t know how since even a tank can’t clear it, but I did and got out of the stream. Even today, when I pass that spot, I measure it. I took up a position and fired my Kalashnikov. I killed the Soviet facing Habib Noor. Habib shouted that Soviets were still in the nearby houses of Shna Kala village. I moved down the path from the bridge to get at the Soviets. I approached that position, threw hand grenades at it and fired my Kalashnikov. Everything was quiet after that. I looked back across the road. Habib Noor was standing. I told him to get down. He remained standing, cursing the Soviets and demanding their surrender in Pashtu. At that moment, I saw a light in his stomach. He was hit and fell down. I recrossed the road to get his body. I could see the bodies of Soviets in the stream. When I reached Habib, he died. He had only five rounds left. He was my good friend and was not even from our village. He was from the Ahmadzai tribe, which live away from this area.

Fighting went on all around us. I heard shooting from everywhere, but I only knew what was going on around me. Shaykh Bombar from my unit came up to help. He had the only other Kalashnikov in my group. He had given his Kalashnikov to another guy and taken the RPG and one rocket and moved to my position. As he came, I saw tanks moving toward us through the fields from the Shna Kala village. The sun was setting. The air assault troops had come down from the mountains and were advancing. Tanks were coming from the west. We wanted to carry Habib Noor’s body to Rangin Kala village and from there it would be easier to take his body out of the area. I took the RPG and rocket from Shaykh Bombar. We wrapped Habib Noor’s body in my tsadar—the all-purpose cloth that we all carry and wear. Then I shot the RPG at a tank. The tanks were out of range and so the rocket landed among the infantry. The tanks and infantry promptly stopped, realizing that we had antitank weapons. Their halt enabled us to break contact and take Habib Noor’s body out of the area to Gerdab village—about six kilometers further to the east. There, I rented a camel and we took Habib’s body to his family at a refugee camp in Pakistan. We buried him in the refugee cemetery in Peshawar, even though his home was in Paktia Province. His family is doing okay now since one of his sons has a job in Saudi Arabia.

COMMENTARY: At this point, the Mujahideen effort was uncoordinated and put the villagers at direct risk. The Mujahideen were poorly trained and their lack of cooperation put the area at risk. Their personal bravery and motivation, however, turned the entire area into a defensive zone that slowed the Soviet effort. Later, as the Mujahideen were better armed, had better communications and began to coordinate their actions, they were more effective against the Soviet and DRA forces. However, by that time most of the civilians were killed or had left the area for refugee camps in Pakistan.

The Soviet effort was well planned and used air assault forces effectively to seal the area. However, their cordon enclosed a large area which they were unable to effectively sweep. They needed to break the cordoned area into manageable segments and sweep those in turn. Instead, their sweep was uncoordinated and large sectors of the green zone were never checked. This green zone is full of villages and fields and requires several days to clear. The Soviets were reluctant to maintain a cordon at night, so they hurried through the sweep and missed the bulk of the disorganized Mujahideen.

In late January 1984, Soviet forces launched a multi-divisional8 cordon and search operation in Parwan and Kapisa Provinces. The aim of the operation was to destroy the Mujahideen forces across a wide area stretching from the Charikar-Salang highway in the west, to Mahmoud-e Raqi in the east and Bagram in the south (Map 10-4 - Parwan). This area is covered with villages and cut by irrigation canals to the orchards, vineyards and farms of this fertile area. There were dozens of Mujahideen bases in this area that were affiliated with major resistance factions. Most of the Mujahideen were not in their bases but split up into hundreds of small units living in the villages during the winter.

On 24 January columns of Soviet and DRA tank and motorized rifle forces moved from Kabul, Bagram, Jabal-e Seraj and Gulbahar (at the mouth of the Punjsher Valley) to establish a wide cordon around the green zone on both sides of the Panjsher River. The cordon and sweep operation was backed with extensive air support. The Soviets and DRA hoped to trap the thousands of Mujahideen in this area and to destroy their base camps. The Mujahideen reinforced their defenses along the major roads in the area. The Mujahideen expected enemy advances along these axes of advance and decided to block them to gain time to break out from encirclement.

During the first day, the Soviet/DRA forces deployed and established blocking positions reinforced by tanks, APCs and artillery. At dawn on 25 January, they mounted attacks from several points, including Charikar, Jabal-e Seraj, Gulbahar, Mahmoud-e Raqi, Qala-e Naw and Bagram.

At that time, Haji Abdul Qader commanded some 200 Mujahideen in the Bagram District. His permanent base was co-located with a JIA base under Commander Shahin at Deh Babi near Abdullah-e Burj. His other base was at Ashrafi near Charikar. His group was a mobile group and spent most of its time fighting around Bagram or combined with other Mujahideen units in Parwan and Kapisa Provinces.

During the Soviet cordon and search operation in Parwan and Kapisa Provinces, Haji Abdul Qader’s unit, along with a 150 strong unit under Commander Sher Mohammad, was to defend a line north of the main Bagram-Mahmoud-e Raqi road between Abdullah-e Burj and Qala-e Beland. To the west, HIH faction Mujahideen were blocking the Bagram-Charikar axis, and on the east flank, JIA units were covering the area on the left bank of Panjsher River (Map 10-4 - Parwan).

The night before the attack, Soviet and DRA artillery pounded Mujahideen positions from fire bases that they established around the area. They attacked swiftly and engaged the Mujahideen on all axes with infantry and armor or pinned them down with heavy artillery and air strikes. Their air force intensified the pressure on the second day as ground attack aircraft and helicopter gunships supported the attacking columns. Mujahideen communications were seriously disrupted and their tactical coordination dropped off dramatically.

Haji Qader ordered his men to occupy prepared blocking positions. They were armed with Kalashnikovs, some 15 RPG-7 anti-tank grenade launchers, three 82mm and one 75mm recoilless rifles, three 82mm mortars, two DShK machine guns and one ZGU-1 heavy machine gun. They also had a few 107mm surface-to-surface rockets. Haji Qader deployed all his anti-tank weapons forward and emplaced his heavy machine guns on the high ground behind the front line. Haji Qader split his force and rotated them in the defensive positions. The Mujahideen who were not manning the positions constituted the reserve and concentrated in Baltukhel and Sayadan, some two to three kilometers to the northwest. Qader’s supplies and aid station were also located in this area.

At dawn on January 25, opposing artillery pounded Mujahideen positions for about two hours. The intensity of fire kept the resistance fighters down inside their bunkers. Some Mujahideen took cover in the ruins and terrain folds and ditches. The artillery fire was accompanied by air strikes and gun runs by helicopter gunships. The Mujahideen did not expose themselves during the fire strikes. A little after sunrise, opposing infantry, backed by tanks and BMPs, launched the attack. The attacking columns moved confidently, assuming that the artillery fire and air strikes had destroyed the Mujahideen resistance. However, as they came within range, Mujahideen anti-tank weapons and machine guns opened up. They caught the attackers by surprise and forced the infantry and tanks to fall back. The attackers were not very aggressive, probably as a result of their fear of mines and anti-tank weapons.

During the first two days, the Soviets repeated their attack several times following the same scenario: artillery fire and air strikes would hammer Mujahideen positions. Then the infantry and tanks would advance until they were stopped with withering fire at close quarter. They would then fall back. The tanks that were following the infantry were very slow to advance, particularly when some tanks were hit and the infantry suffered casualties. At the same time, the infantry would lose heart after being hit by withering defensive fire and would fall back to take cover behind the tanks.

As the operation continued, two factors worked against the Mujahideen. First, the enemy penetrated Mujahideen positions to considerable depth on some axes. This raised the fear of being encircled by flanking units. Second, as the Mujahideen began to understand the scope and intent of the enemy operation, they began to escape out of the enemy cordon. This weakened the Mujahideen positions and aided the attacker. Some adjacent units left their forward positions at the Qala-e Belend sector and fell back. This forced Haji Abdul Qader to withdraw his force on the third day to his planned second line of defense on high ground about one kilometer north of the forward defensive positions. For the next three days, the Soviets tried to break through Qader’s positions on the high ground. It was even tougher going for them. They used the same method of assault with the infantry leading and the tanks following—and with the same results.

Toward the end of the week, hundreds of Mujahideen used the Qala-e Beland sector as an escape route to their mountain bases in Koh-e Safi in the south. The Mujahideen used a covered irrigation canal to sneak out of the area. Just north of the road near the Qala-e Naw bazaar, there is an east-west irrigation canal. Several north-south feeder canals intersect this main canal. At several points, the canal is bridged and covered to allow vehicles to cross. At these points, the main and feeder canals are covered. In winter, the irrigation system is dry and provided suitable escape passages. During the last nights of the operation, hundreds of Mujahideen escaped through the canals to Koh-e Safi. The attackers detected this exodus only toward the end of the operation and opened fire on some escapees. Haji Abdul Qader’s men provided the rear guard and were the last to move out of the area after blocking the Qala-e Beland sector for one week.

When the Soviets and DRA finally entered the area, thousands of Mujahideen had escaped. Haji Qader claims that the Soviets only captured about 20 armed Mujahideen and that the Soviet commander in charge of the operation was reprimanded for his failure. He states that the Soviets used several divisions, made elaborate plans and fired thousands of artillery shells and flew hundreds of combat missions without achieving much. Haji Abdul Qader’s group destroyed 11 tanks and APCs and inflicted dozens of casualties on the enemy. His losses included seven KIA and 18 WIA. Most of his casualties came from helicopter gunships.

COMMENTARY: Although the Soviet/DRA forces overran many Mujahideen bases in Parwan and Kapisa Provinces, they failed to destroy the Mujahideen forces which slipped out of the cordon or went underground. The Mujahideen enjoyed freedom of movement and maneuver in a large area until the Soviets and DRA finally penetrated. The Soviet/DRA encirclement was very porous—as was the case with so many large-scale cordon and search operations of the war—making it impossible to trap Mujahideen forces. The poor performance by the Soviet infantry and tanks against a determined enemy cost them dearly. Instead of mounting coordinated infantry-tank assaults, the Soviet forces seemed to use each element separately. While a combined action could minimize the vulnerabilities of each element, a disjointed action maximized the vulnerability of both elements in the face of a resolute defense.

The Mujahideen built a series of covered bunkers near their prepared fighting positions and these bunkers enabled them to survive air strikes and intense artillery barrages. Most of this massive Soviet fire destroyed civilians, houses and the agricultural system.

Lack of operational coordination among the Mujahideen groups cost the resistance some major operational achievements. While the Soviets failed to capture large numbers of Mujahideen or to destroy a major Mujahideen grouping, the resistance missed a major opportunity to inflict heavy losses on the Soviets. The Mujahideen focused on escape, when they had many chances to bloody their enemy by resisting on consecutive defensive positions in the area and by cutting the Soviet withdrawal routes once they were inside Mujahideen territory. However, this was not the first nor the last battle for the resistance. They were fighting a war of attrition and refused to become decisively engaged in their home area where the civilians and villages would bear the brunt of the damage. In this area, the civilian population remained in their homes throughout the war.

Tactically, the Mujahideen massed the fires of their light anti-tank weapons at close range. Several anti-tank gunners would fire at the same target simultaneously. This greatly increased their probability of hit, prevented effective counter fires, demoralized vehicle crews, created confusion among their enemy’s tank and motorized columns and prevented the employment of accurate, Soviet indirect artillery fire into the area. Heavy machine guns usually backed up the anti-tank gunners to separate the dismounted infantry from the armored vehicles, keep the vehicle crews buttoned up so that their vision was obscured, and provided covering fire should the anti-tank gunners need to leave their positions.

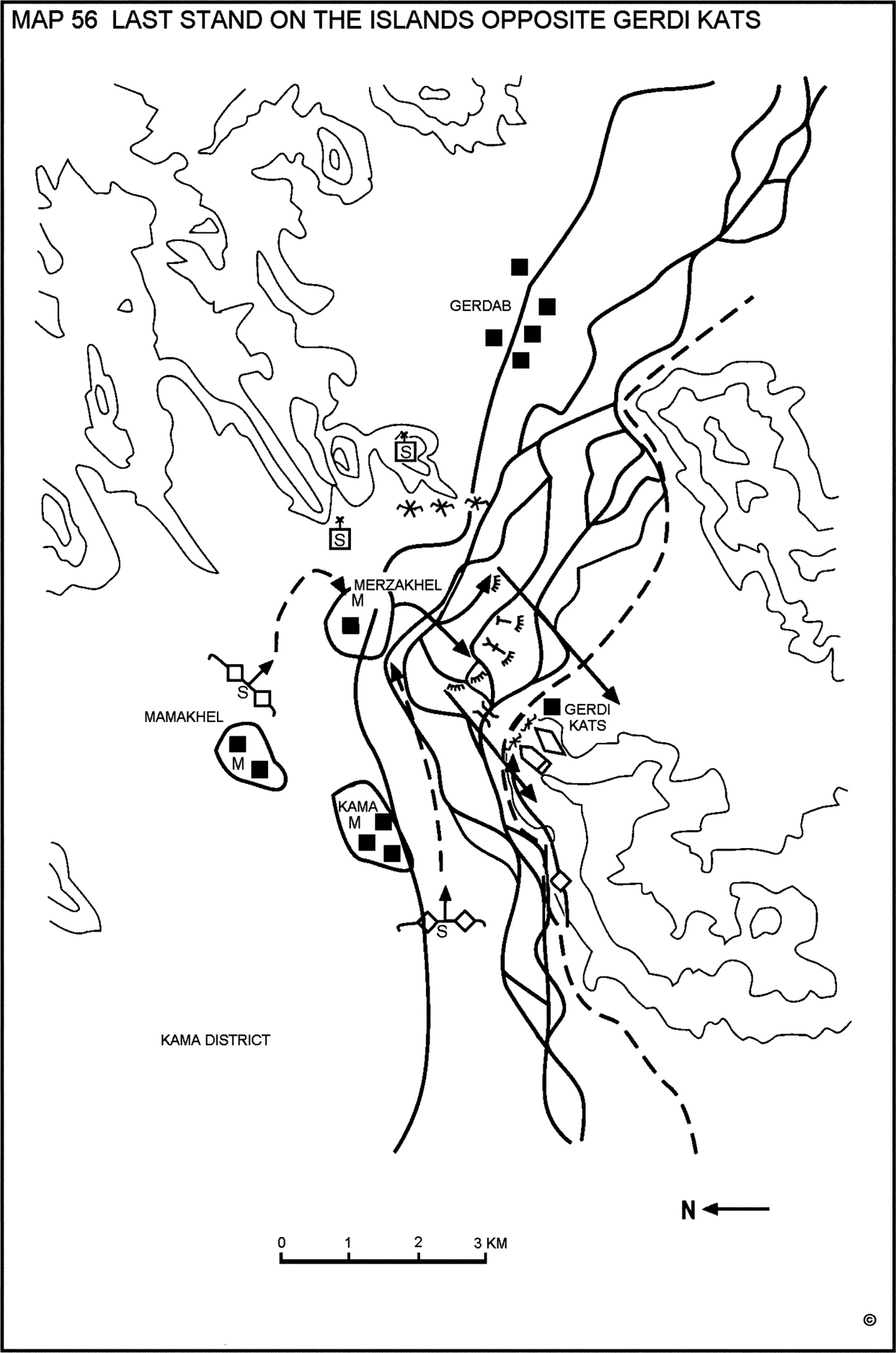

On 24 March 1984, the Soviets sent a large force into Kama District. I was in Peshawar, Pakistan at that time. The Soviet force was not just the 66th Brigade, but also included a force which came from fighting in Laghman Province. The entire force had some 200-300 tanks and APCs in it. I had two groups of Mujahideen in the village of Merzakhel. One group was commanded by Baz Mohammad and the other by my nephew Shapur. Baz Mohammad’s group managed to get out of Merzakhel before the Soviets arrived but Shapur’s group of 25 was trapped. The Soviets landed troops on the high ground overlooking Merzakhel and their tanks were moving in from the west (Map 10-5 - Gerdi). Across the river, Soviet tanks were moving through Gerdi Kats. The Mujahideen moved south from Merzakhel to the low, flat islands of the Kabul River between Gerdi Kats and Merzakhel. These islands are covered with a low-scrub which offers some concealment but not cover. As they reached the islands, the Soviet infantry in Gerdi Kats began to cross the river with inflatable rubber rafts. The Soviets also moved a tank into the river to cross over, but it quickly became stuck. Fairoz, a Mujahideen machine gunner, sunk the rafts with PK machine gun fire. The Soviet infantry sunk into the river and several drowned. The Soviets also had two dogs on the rafts. The dogs swam back to Gerdi Kats. Mujahideen fire from the islands pinned down the Soviets and defeated their crossing attempt.

However, at the same time, the enemy brought pressure on my group from both sides and only a few of my men managed to slip away. They were exposed on the low-scrub islands and I lost 11 KIA, two WIA and two captured. The two captured were Awozubellah and Nazar Mohammad. The Soviets tortured them, but they did not break. They continually claimed that crazy Mawlawi Shukur forced them to fight. Eventually, they were released. Shapur and Fairoz were wounded. Villagers took them to safe houses and kept moving them to hide them from the Soviets, who searched the area for six days. We could not retrieve our Mujahideen dead due to enemy pressure. Many of their remains were torn apart by foxes and jackals. After a week or so, we buried what remains we could find. The Soviets paid a 20,000 Afghanis reward for recovering their dead from the river. When I saw the condition of my dead, I banned Afghans from helping the Soviets recover their dead. “Let the crows of this country have their fair share.”

COMMENTARY: The Kama Mujahideen usually tried to avoid the Soviet cordon and search of their district by fleeing into the mountains, but the Soviets habitually used heliborne forces to block their escape routes. This meant that the Kama Mujahideen fought the Soviets within the green zone. However, the Kama green zone had a road network within it and the Soviets could bring their combat vehicles into the green zone where their firepower gave the Soviets a tremendous advantage. The Soviets used the same mountain LZs over and over again, but the Mujahideen made no attempt to mine the LZs or post antiaircraft weapons overlooking these sites on a permanent basis. In this action, the Mujahideen were surprised and unable to escape into the mountains and forced to fight an uneven battle. If they had contested the known LZs, the outcome should have been less costly for the Mujahideen.

Crossing shallow desert rivers looks fairly safe, but can be treacherous. On the 31st of March 1879, the British Army lost 47 men, effectively a squadron of the 10th Hussars, crossing the Kabul River some 35 kilometers to the west of this Soviet crossing attempt. The Kabul River looks shallow and slow-moving, but it has fast, strong undercurrents that can quickly overpower the unwary soldier.

The Soviet/DRA cordon and search usually involved a number of forces in a combined arms battle or operation. The Mujahideen who had the best success surviving these did so because their actions were centrally coordinated, they had developed contingency plans to deal with them and they had built redundant field fortifications to slow the Soviet/DRA advance and fragment their efforts. The better-prepared Mujahideen always retained a central reserve and were adept at counterattacking the flanks of the attacker. The Mujahideen who had the most difficulty with cordon and search operations were usually separate groups who had little or no ties to a central Mujahideen planning authority, had worked out no contingency plans and had taken no steps to fortify the area.

Commander Qazi Guljan Tayeb was a third year student in Kabul Theological College during the communist takeover in 1978. He joined Hikmatyar and later switched to the Sayef faction in the mid-1980s. He was the Commander of Baraki Barak District of Logar Province. [Map sheets 2784, 2785, 2884, 2885].

1 Forces on the Gardez axis were from the Soviet 56th Air Assault Brigade and the DRA 12th Infantry Division. Forces on the Kabul and Wardak axes were probably from the Soviet 103rd Airborne Division and 108th Motorized Rifle Division, while DRA forces were probably from the 8th Infantry Division, 37th Commando Brigade and 15th Tank Brigade.

2 Ziarat means shrine.

3 The AK-74 Kalashnikov 5.56mm assault rifle was issued only to Soviet troops. DRA troops had the older AK-47 Kalashnikov assault rifle. The Mujahideen called the AK-74 the “Kalakov”. One of the Pashtun songs of the time had a line “A mother should not mourn a son killed by a Kalakov” This meant that her son died fighting Soviets.

Tsaranwal (Attorney) Sher Habib commanded the Ibrahimkhel Front north of the city of Paghman. His primary AO extended from Paghman east and northeast to Kabul (some 20 kilometers). [Map sheet 2786, 2886].

4 The forces on the main axis were probably from the Soviet 108th Motorized Rifle Division, while DRA forces were probably from the 8th Infantry Division, 37th Commando Brigade and 15th Tank Brigade. The forces on the northern axis were probably from the Soviet 103rd Airborne Division.

Abdul Baqi Balots was a Hezb-e Islami (HIH) commander in the Kama area east of Jalalabad. Before the communist takeover, he was a student in the tenth grade of high school. School authorities were forcing him to join the Communist Youth Organization. His father advised him not to join but to fight. He left school and joined the Mujahideen and fought through to the end. [Map sheets 3085 and 3185].

5 The US M1917 Springfield Rifle which Springfield Armory produced for the British Army in World War I. The Mujahideen called them the G3 rifle.

6 The “Thunder” unit was the 66th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade. The Mujahideen called it the Thunder unit because it was a reinforced unit designed for counterinsurgency. It had three motorized rifle battalions, an air assault battalion, a tank battalion, an artillery howitzer battalion, a MRL battalion, a material support battalion, a reconnaissance company and support troops.

7 Marko is the Chinese copy of the German M-88 Mauser.

Mawlawi Shukur Yasini is a prominent religious leader in Nangrahar Province. He is from the village of Gerdab in Kama District northeast of Jalalabad. During the war, he was a major commander of the Khalis group (HIK). Later, he joined NIFA. During the war, he took television journalist Dan Rather to his base in Afghanistan. He also accompanied Congressman Charles Wilson of Texas into Afghanistan several times. During most of the war he was active in his own area fighting the DRA in Jalalabad and the Soviet 66th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade at Samarkhel. He became a member of the Nangrahar governing council after collapse of the communist regime-a position he held until the Taliban advance in September 1996. [Map sheet 3185].

Haji Abdul Qader was a commander in the Bagram area. The authors have consulted other documents to add detail to his account. A former teacher, Abdul Qader hails from the Sayghani village just six kilometers northeast of the Bagram air base. His group was initially affiliated with the HIK faction. He later joined Sayyaf’s IUA faction. [Map sheets 2886 and 2887].

8 Most probably the Soviet 103rd Airborne Division and the 108th Motorized Rifle Division and the DRA 8th Infanfantry Division and 37th Commando Brigade.

9 Colonel H. B. Hanna, The Second Afghan War, 1878-79–80, Its Causes, Its Conduct, and Its Consequences, Volume II, Westminister: Archibald Constable and Co., Ltd., 1904, 282-287.