Although guerrilla forces would like to retain the initiative and never have to defend, there are times when the guerrilla force must defend. The guerrilla can conduct a mobile defense or a positional defense. Guerrilla mobile defenses are usually rear-guard actions designed to preserve the main force or draw the attacker into a prepared ambush. Guerrilla positional defenses are normally associated with the defense of a pass, bridge, populated area, base camp or supply depot. The odds are stacked against the defending guerrilla. The attacker has the initiative, armored vehicles, air power, the preponderance of artillery and overwhelming firepower. The guerrilla tries to match this through use of terrain and prepared defenses.

In the Soviet-Afghan war, the Mujahideen spent a great deal of time and energy in the defense. Mujahideen defense was associated with Mujahideen logistics. Early in the war, Mujahideen logistics requirements were primarily concerned with ammunition resupply and medical evacuation of the wounded. The rural population willingly provided food and shelter to the Mujahideen, since the Mujahideen were mostly local residents. The Soviets decided to attack Mujahideen logistics by forcing the rural population off of their farms into refugee camps in Pakistan and Iran or into the cities of Afghanistan. They did this by bombing and attacking villages, scattering mines across the countryside, destroying crops, killing livestock, poisoning wells and destroying irrigation systems. The Mujahideen, accustomed to living off the good will of the rural population, were now forced to transport rations as well as ammunition from Pakistan and Iran into Afghanistan. The Mujahideen created a series of supply depots and forward supply points to provision their forces. These depots and supply points had to be defended. The Mujahideen also controlled key passes, which forced the Soviets and DRA to either withdraw cut-off forces or resupply them by air. The Mujahideen defended these key passes zealously.

The rugged terrain of Afghanistan aided Mujahideen defenses. Defensive positions were another key component of the Mujahideen defens. Mujahideen built rugged, roofed bunkers which could withstand artillery and airstrikes. The Mujahideen built elaborate camouflaged defensive shelters and fighting positions connected with interlocking fields of fire, communications trenches, and redundant firing positions. The Mujahideen learned to rotate defensive forces through a position to lessen the effects of combat fatigue and psychological stress.

What follows are examples of successful and unsuccessful Mujahideen base camp defenses against ground attack or a combination of ground and air assault.

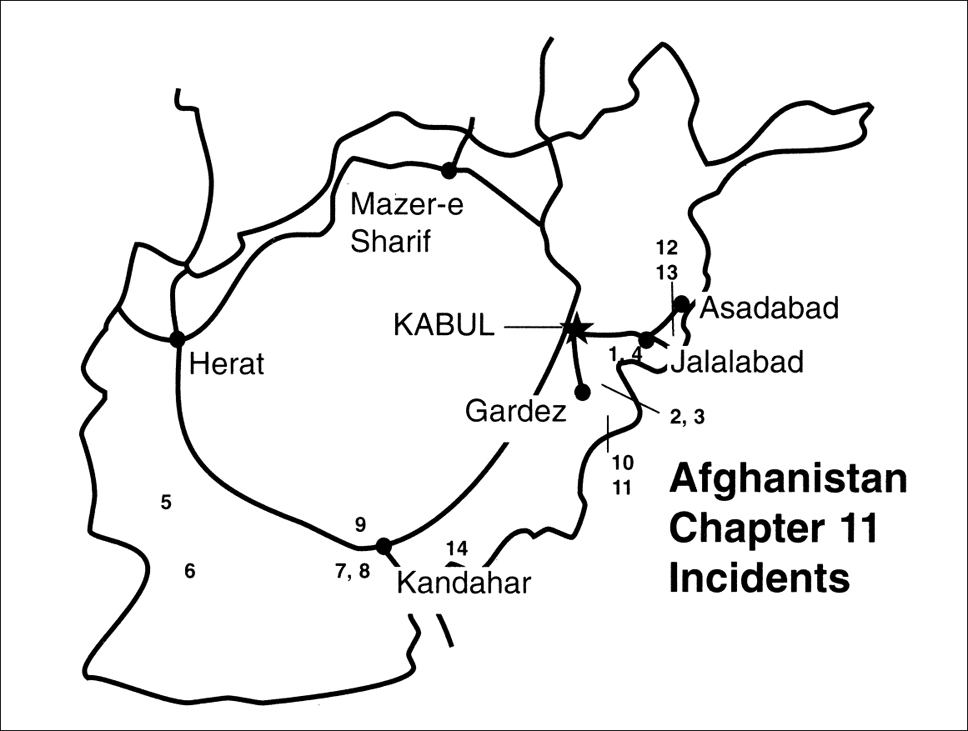

During 1978-1979, the heavily-populated Surkh Rud District was a hotbed of resistance against the communist regime and a base for Mujahideen actions in Nangrahar Province. Following the Soviet invasion, one of the early major Soviet operations was conducted against Mujahideen bases in Surkh Rud. There are two main roads running northeast to southwest in Surkh Rud Valley (Map 11-1 - Chaharbagh). Highway 134 runs through Chaharbagh, Watapur, Surkh Rud (the district headquarters), Khayrabad, and Fatehabad. The other road runs along the bottom of Tor Ghar mountain. It passes through Darunta, Katapur, Balabagh, and then follows the Surkh Rud River to the west. Most of the Mujahideen bases were located along these two roads and most Mujahideen bases also maintained hideouts in the canyons of the Tor Ghar mountain. My home town of Bazetkhel was located between the two roads, but my base was just to the east of Highway 134.

The Soviet forces concentrated in Jalalabad in May 1980. We were tipped off that the Soviets planned to advance along the two roads, destroying Mujahideen bases as they went. Their southern column would swing north at Fatehabad to seal the pocket. I left my base at Chaharbagh and went to my village at Bazetkhel, where I had 80 men. I took 50 of these men north into a Tor Ghar mountain canyon. We intended to stop the Soviet column on the northern route before they reached the main Mujahideen base at Katapur. We also hoped to buy enough time to allow the civilians to escape into the mountains. When the column approached, my force engaged them and we stopped the column. The Soviets dismounted and began moving aggressively into the mountains. They were a bit too aggressive and our fire cut them down. The Soviets were badly bloodied. The Soviets responded by calling in massive artillery fire on my positions. When night fell, I pulled my force further up the canyon to the mountain ridge and then crossed over into the next canyon to the west. We moved down the canyon and into the town of Katapur.

At Katapur, the local Mujahideen told us that Soviet troops had chased the civilians into the mountains just north of Katapur and killed many of them. During the fighting near Katapur, the Soviets had left two of their dead behind. The Mujahideen expected that the Soviets would return for their dead. My Mujahideen joined other Mujahideen and we went to defend a canyon to the north of Katapur. We laid an ambush on the high ground. Soon, a Soviet detachment appeared looking for their dead. We opened up on the Soviets and they left seven more dead behind. However, they retaliated on the villagers and massacred civilians and even animals in Balabagh and Katapur and then moved on to Fatehabad. The Soviets could not dislodge the Mujahideen from the mountains and could not find us in the valley, so they killed everything in sight. They established three bases—at Balabagh, Fatehabad and Sultan Pur. The Soviets launched search-and-destroy missions from these bases against the adjacent villages. Many civilians had to flee west while Mujahideen detachments went to their hideouts in the Tor Ghar mountain. Mujahideen commanders calculate that the Soviets massacred some 1,800 people during 12 days in the Surkh Rud. Most of these were innocent civilians. The Soviets expected that they could readily flush out the Mujahideen. Their lack of success led to frustration and the Soviet soldiers ran amok—killing and looting. It was the first Soviet operation in the area. They came looking for U.S. and Chinese mercenaries and instead found frustration and an opportunity to murder and loot.

COMMENTARY: During this stage of the war, the Mujahideen lived in their own houses in the midst of the population. Their food, water and shelter was willingly supplied by the populace. As a result, many civilians died when the Soviets launched their operation. The large number of reported civilian deaths could be a result of lack of officers’ control and unit discipline or deliberate policy. The apparent Soviet plan was to separate the guerrilla from the populace by forcing the populace out of the countryside. Later, most of the populace deserted their homes in this area and fled to refugee camps in Pakistan.

This is too large an area to block and sweep as a single action and the Soviets failed to segment the area and clear it a piece at a time. This allowed many of the Mujahideen and civilians to escape the cordon. The Soviet emphasis on the primacy of the large operation instead of the well-executed tactical action worked to the Mujahideen advantage. Mujahideen command and control was fragmented and worked through happenstance and chance encounters. Without advanced warning, the Mujahideen would probably have suffered much more in this sweep.

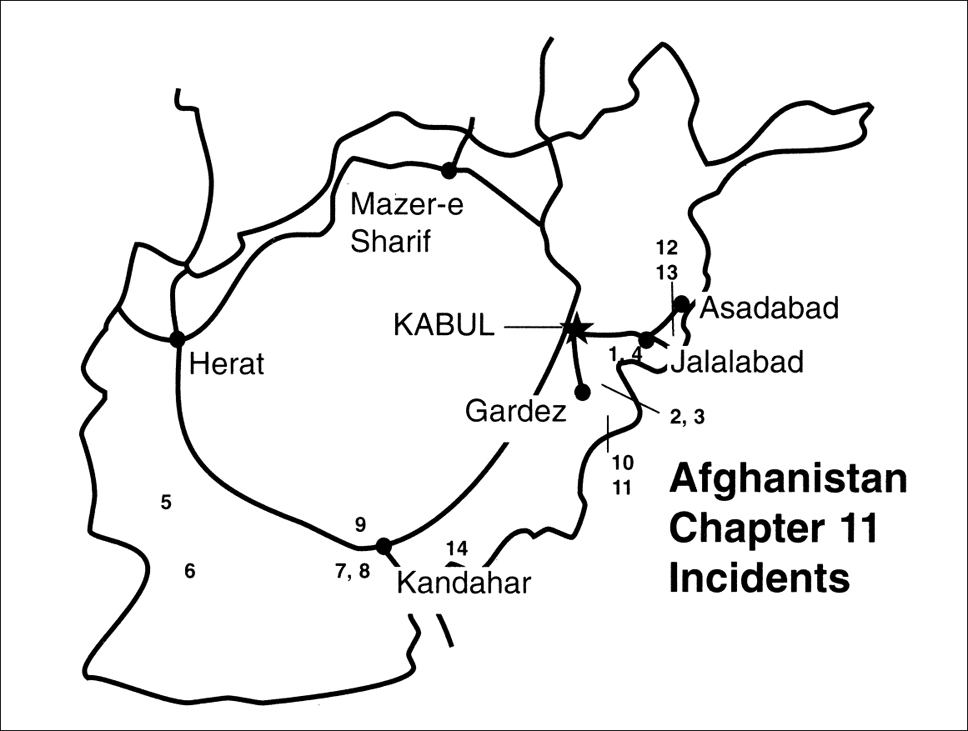

In 1980, the Mujahideen began establishing bases in the mountains near the village of Surkhab in Lowgar Province. There were perhaps 150 Mujahideen in the area belonging to several factions. Mawlawi Mohammad Yusuf of the ANLF, Mawlawi Mohammadin of the IRMA and small groups from JIA and IUA established bases there. My base was in the mountains east of Surkhab in a canyon called Durow. We had 82mm mortars, DShKs and RPG-7s. Early in the morning of the 5th of June 1980, a mixed DRA/Soviet column came from Kabul and exited highway 157 at Pule-e Kandahari heading east. They were coming for us. They deployed their artillery and began shelling our bases. Most of the Mujahideen were in their villages at that time. They came out of their villages and occupied defensive positions while other Mujahideen joined them from their mountain bases.

In order to block the advance of the enemy into our mountain bases, we occupied blocking positions on Spin Ghar mountain overlooking Dara village (Map 11-2 - Surkhab). Other Mujahideen occupied positions south of Durow Canyon on Lakay Ghar mountain. Our original plan was to defend the forward slopes of Spin Ghar and Lakay Ghar. We set an ambush forward of our main defenses. It inflicted casualties but was eventually overwhelmed. After their artillery preparation, enemy tanks and infantry moved along the valley road from Korek and attacked Mujahideen positions at the canyon’s western mouth. Fighting was heavy. This was our first experience fighting the Soviets. Their helicopters came in to evacuate their dead and wounded. Our civilians suffered horribly. The people began leaving their homes and fleeing to the mountains. Fighting continued all day long, but the enemy was unable to break through the Mujahideen positions.

On the second day, there were fewer Mujahideen fighting, as some had left the area overnight. The enemy firing kept tremendous pressure on the remaining Mujahideen and many had to withdraw from their fighting positions. There is a covered approach to Spin Ghar mountain from the north using the Tobagi plain. This plain is higher than Surkhab village and it is easier to climb Spin Ghar mountain from the Tobagi plain than from the Surkhab Valley. I was climbing the mountain with two others carrying ammunition. I intended to climb over the mountain to the north face. As we reached halfway up the ridge, enemy aircraft flew over the area. The enemy usually marked their infantry positions for the aircraft by firing smoke or signal rockets. We saw rockets being fired on the other side of the mountain. This meant that enemy infantry were on the other side of the mountain and were trying to encircle the Mujahideen bases by a flanking movement from the Tobagi plain. I had all our spare ammunition with me and at that time ammunition was as precious to me as my faith. We climbed back down the mountain and saw that the other Mujahideen were retreating into their bases. The people of Surkhab came to the Mujahideen and demanded that we move our bases lest Surkhab be invaded everyday. The Mullas had refused to move the bases earlier, but now they were panicked and hiding in caves. The people taunted them with “You told us this was Jihad, but now you are trying to flee.” Some of the Mullas came out, but everyone was still panicked. I had all of this ammunition and no one to help me move it. I thought of abandoning the ammunition and saving my skin, but then I thought how vital the ammunition was and what would happen if I was later called to account for my actions.

Finally, a group of us decided to make a suicidal last stand and called for volunteers. Lieutenant Sharab, a DRA deserter, volunteered. We had suspected him earlier, but he proved himself now. Lieutenant Sharab said, “They are not used to mountains. It will take them a long time to climb them and they are afraid of these mountains. If you fire at them from one position, they will stop and return fire for a long time at that position.” We fired mortars at the north slope and positioned some Mujahideen on the top of Spin Ghar mountain to draw fire. This was the turning point. All of a sudden, helicopter activity fell off and firing tapered off in the valley. We thought that it was a trick to make us believe that the fighting was over so the Mujahideen would come out of their hideouts and then they would take us from behind. We did not expect that such a powerful enemy would abandon an almost certain victory and retire empty-handed. It was late afternoon when I saw civilians coming from Surkhab. They told us that the enemy had withdrawn. The enemy evidently did not want to have to fight to take the mountain. This was not our doing, but the hand of God. We lost 10 KIA and six WIA in my group. I do not know the casualties in other groups. All the wounded who could walk, walked to Pakistan for treatment. The other wounded were treated by local doctors. Doctors from Kabul hospitals would come to help us also. Dr. Abdur Rahman from a hospital in Kabul would often treat our wounded. I do not know what the enemy losses were, but they must have suffered a lot to quit on the brink of victory.

COMMENTARY: The DRA/Soviets had the opportunity to attack the eastern and western canyon mouths simultaneously. The Mujahideen defenses were oriented to the west. Even on the second day, when the DRA/Soviets tried to envelop the Mujahideen position from the Tobagi plain, they did not hook around the mountain, but tried to go over the mountain. The Mujahideen were used to the mountains, whereas the Soviets were not and their equipment was not designed for climbing in mountains. Later in the war, the Soviets issued better equipment for fighting in the mountains and began training their soldiers at mountain warfare sites. At this point, the non-nimble Soviets and the reluctant DRA were no match for the Mujahideen in mountain maneuver. They should have taken the canyon from both ends. Further, if the DRA or Soviets had covertly moved some artillery spotters onto high ground before the offensive, they could have unhinged the Mujahideen defenses before they were established.

The Soviets had not yet developed their air assault tactics for counterinsurgency. The mountain tops of Spin Ghar and Lakay Ghar can handle heliborne landings and the Mujahideen air defense posture was negligible at this point. A small Soviet force, reinforced with mortars, artillery spotters and forward air controllers and machine guns could have created havoc from the mountain tops.

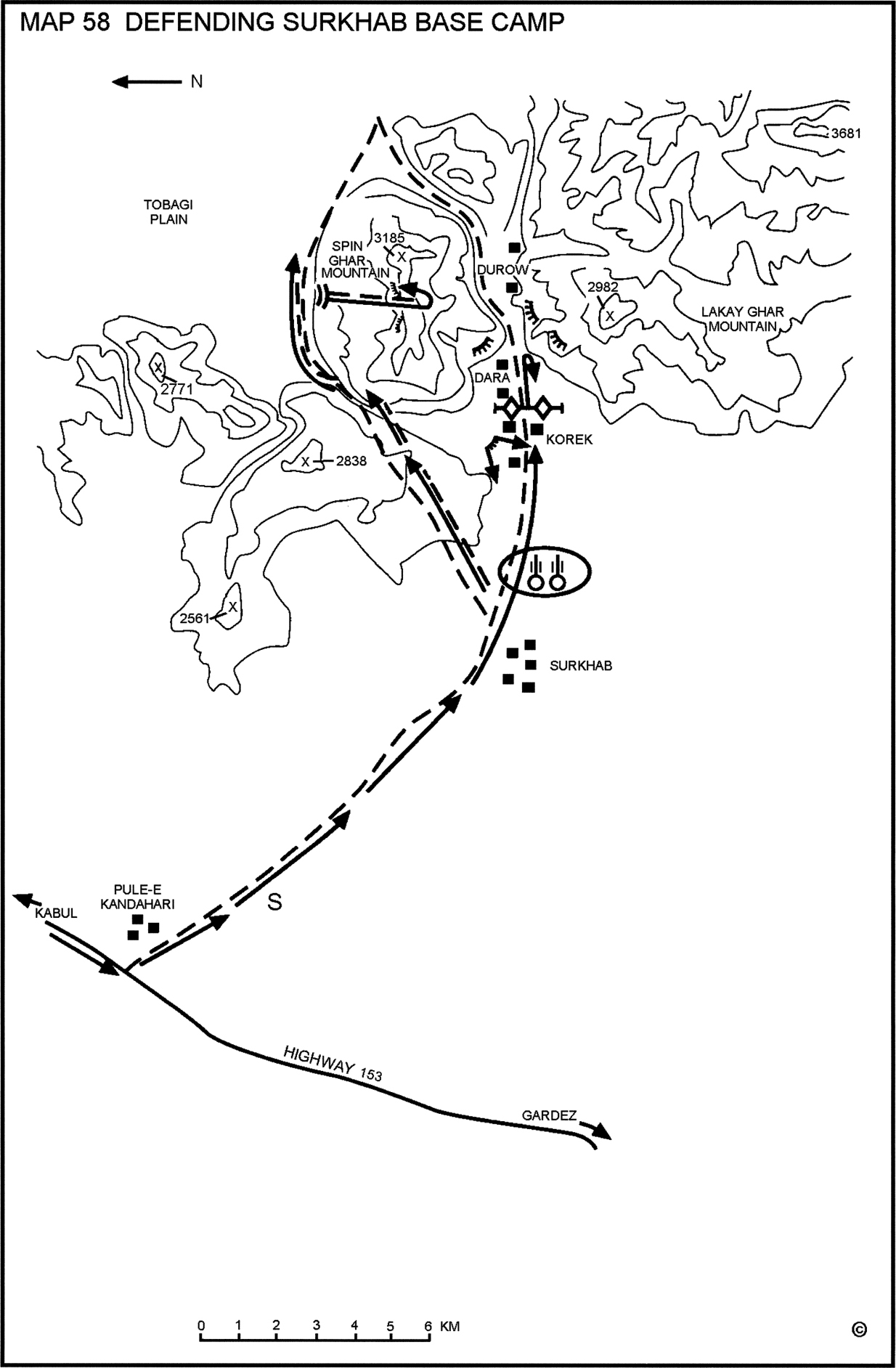

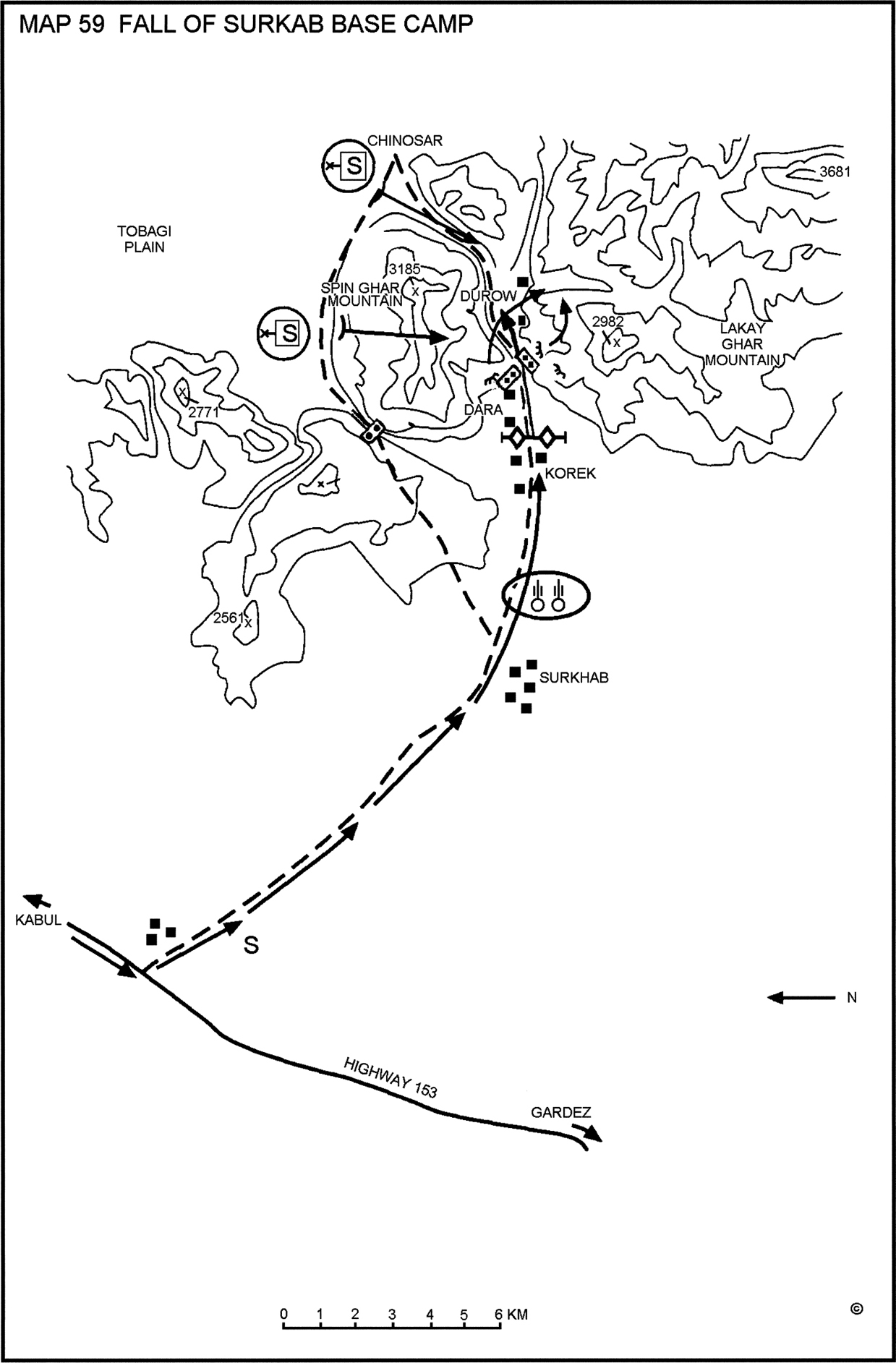

In early September 1983, we laid an ambush at Pul-e Khandari on Highway 157, the major road between Kabul and Gardez. At that time, Mujahideen ambushes were hurting the DRA/Soviet efforts to keep Gardez supplied. The enemy convoys always left Kabul in the morning. We would get into position in the morning and wait until afternoon. If no convoys had shown by afternoon, we would quit and go back to base or go take a nap in the villages. The enemy finally figured out that we were reacting to their pattern and changed their pattern. They started moving their convoys in the afternoon on the assumption that we Mujahideen would have abandoned the ambush sites, since it was long past time for the convoy to arrive. As usual, we set up our ambush in the morning and waited. No convoy came. We left the ambush site and, by late afternoon, most of the Mujahideen had left the area. Then the column of some 180 trucks arrived. What Mujahideen were left in the village ran to the road and engaged the supply convoy which was hauling ammunition, fuel and food. We got part of the convoy and divided the booty among the Mujahideen groups that had representatives at the ambush. My group managed to capture some ammunition trucks, which we drove to our base near Surkhab in Durow Canyon.

A few days later, a major enemy force moved against our base camps to retaliate for this attack. They kept the area under seige for eight days. We had a total of about 300 Mujahideen from various groups in the area at this time. Our heavy weapons were DShK machine guns and mortars. We had expected some retaliation, so we had prepared defensive positions on the ridges on both sides of the canyon mouth and laid some antitank mines in the area. We also laid an antitank minefield on the trail to the Tobagi plain (Map 11-3 - Surkhab2). The enemy column came through Pule-e Kandahari. They attacked and lost some Soviet armored vehicles to mines on the northern and southern approaches to the canyon. Mujahideen fighting positions on the high ground overlooked these minefields, so we could fire on the advancing enemy as they tried to get through the mines. This slowed the enemy, but we also took losses from their aerial bombardment. We held on and managed to stop the enemy advance. The enemy evacuated their damaged tanks and armored vehicles.

After one week of fighting, the enemy reinforced his effort. Some of the Mujahideen had left since the enemy was stopped and they had to take care of their families. The enemy employed air assault forces, which they landed on the Tobagi plain and at Chinosar at the eastern mouth to our canyon. They had outflanked us. Now the enemy renewed his offensive with an attack against the western and eastern mouths of the canyon and over the Spin Ghar mountain. We could not hold and withdrew from our western positions on Spin Ghar and Lakay Ghar mountains. We torched the trucks that we had captured to prevent their recapture. The enemy reached our canyon village of Durow and found the burnt-out hulks. We moved east into the mountains and harrassed the enemy with mortar fire, but they now controlled our base camps. They destroyed what they could and left. As they left, they scattered mines in some areas.

COMMENTARY: By 1983, the Soviets were using their air assault forces more aggressively, but still not landing them directly on the objective. In this case, Soviet air assault forces landed on Tobagi plain and then climbed to the top of Spin Ghar mountain. By 1986, Soviet air assault forces would be landing directly on the objectives.

The Mujahideen were tied to their bases and had to defend them. This logistic imperative provided some advantages to the DRA and Soviets, who knew that the one way to get the Mujahideen to stay in an area where they could concentrate air power and artillery against them was to locate the Mujahideen logistics base and attack it. Still, the Soviets and DRA seldom did anything to “close the back door” to the base while they attacked it. Consequently, many Mujahideen lived to fight another day. Long range reconnaissance patrols, scatterable mines, helicopter-landed ambush forces and conventional forces in backstop positions are ways to prevent the escape of guerrilla forces.

The Mujahideen appear to have done little to improve their defenses since this same base camp was almost overrun in June of 1980. The DRA and Soviets knew where this base camp was and how it was defended, yet the Mujahideen established no eastern defenses. The Mujahideen’s one improvement appears to be mining the approach to the Tobagi plain, but they had no force guarding that minefield. The Soviets flew over that minefield anyway.

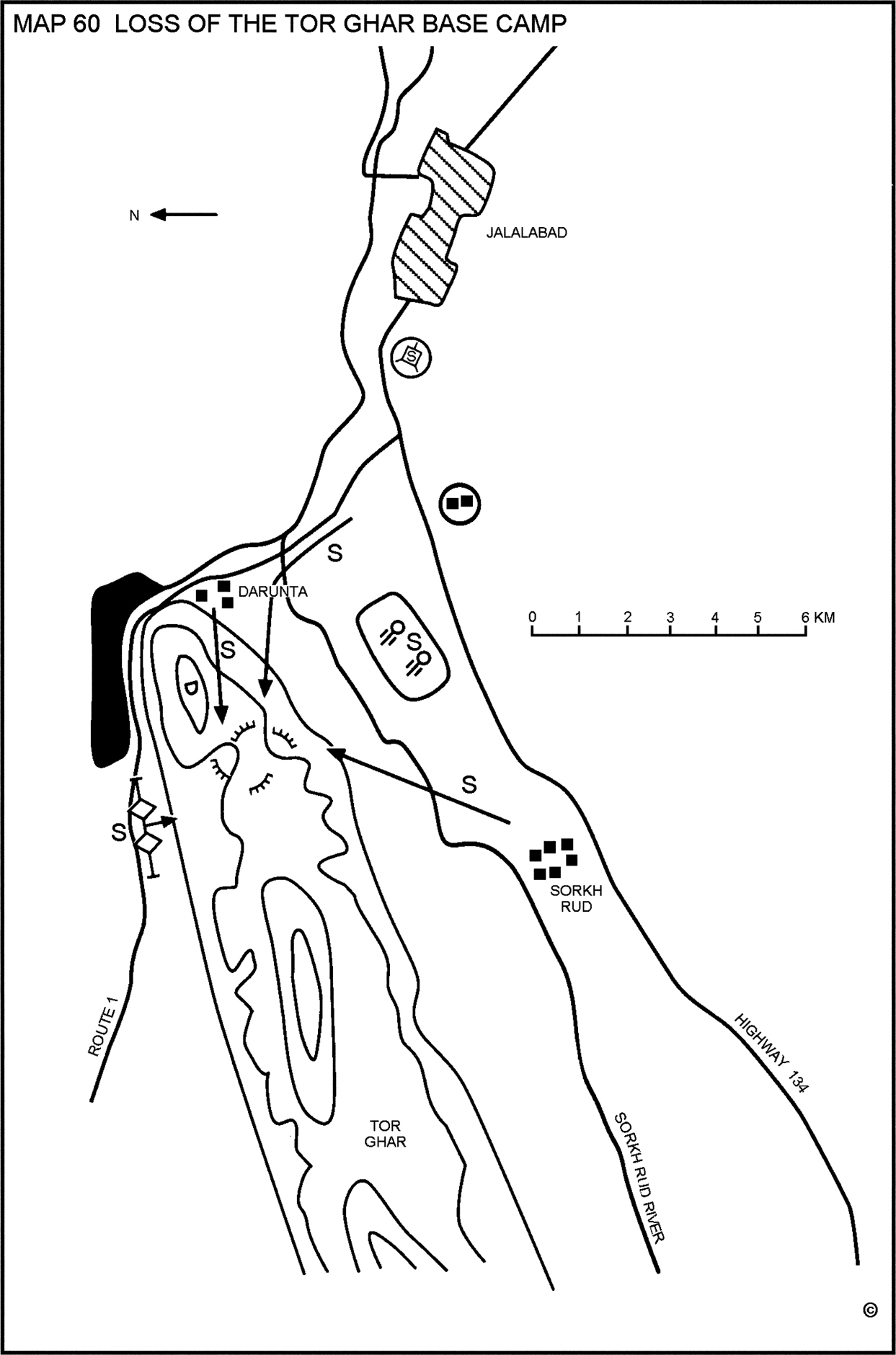

Tor Ghar mountain lies eight kilometers northwest of Jalalabad. Adam Khan and Rasul Khan established the Tor Ghar Mujahideen base but were killed in early fighting. In 1980, the overall commander of the base was Qari Alagul. The base held some 200 Mujahideen from four or five factions. I was a subgroup commander under Commander Abdullah at the time. We had bases at both Chaharbagh and Tor Ghar and regularly launched attacks against the Soviets from Tor Ghar. Our contacts in the DRA had told us that the Soviets would soon attack Tor Ghar in retaliation. Late one afternoon in July 1980, our DRA contacts told us that the Soviets were coming that night. I was with my group in Chaharbagh on the southeast side of the mountain. Commander Abdullah was at the Tor Ghar base. We immediately sent him a note to warn him and asked him to bury the ammunition and everything else since the Soviets would come in strength and Abdullah’s force could not expect to hold them. Abdullah sent a note back to us. “As long as you hear my 20-shooters,1 you know that we are holding. We will swear on the Koran not to leave our position.” Abdullah had 25 men armed with RPGs, Kalashnikovs, Bernaus and bolt-action rifles.

The Soviets attacked from several directions (Map 11-4 - Tor Ghar) launching advances from Sorkh Rud, Jalalabad and Darunta. I withdrew my group from Chaharbagh. Soviet tanks deployed along the road on the north-west side of the mountain and fired on the base. BM-21s fired from Jalalabad. Artillery and BM-21s fired from multiple artillery sites. Helicopters strafed the area. They set the mountain on fire. Then the Soviets climbed the mountain, reached the base and fought for three days. In places, it was hand-to-hand combat. We could not break into the area to help, since the Soviets had sealed the area. Our Mujahideen fought until their ammunition was gone and died to the last man. The Soviets destroyed the bases and infested that mountain with mines.

COMMENTARY: Mujahideen insistence on holding base camps cost them dearly. At this point in the war, base camps were not essential to Mujahideen logistics and Abdullah’s base camp was not the only one which the Soviets overran. It was a pointless battle which could have been avoided by the Mujahideen. When the Mujahideen held real estate, it allowed the Soviets to concentrate their superior firepower on the Mujahideen.

Sharafat Koh is a large mountain southeast of the city of Farah. It is located between the paved road running between Kandahar and Herat (Highway 1) and the Daulatabad-Farah road (Highway 517). The real name of the mountain is Lor Koh, but we Mujahideen renamed it Sharafat Koh (Honor Mountain).2 The mountain is a roughly rectangular-shaped massif with a plateau on top. It rises some 1,500 meters above the surrounding desert and its sides are steep. It covers over 256 square kilometers and is often snow capped. Many large and small canyons (kals) cut into the mountain. On the north side is the Shaykh Razi Baba Canyon (Map 11-5 - Sharafat—red and blue graphics apply to last battle). To the northwest is the Kale-e Amani Canyon. This canyon was populated by ancient peoples and you can see their drawings of hunters with bows and arrows on the rocks. To the west is the Kale-e Kaneske Canyon. The Jare-e Ab Canyon faces southwest and links with the Kal-e Kaneske Canyon at the top. To the south is the Tangirá Canyon which had the most water, but which the Mujahideen usually avoided since it was the only canyon wide enough for armored vehicles to enter. Facing south, and further to the east is the Khwaja Morad Canyon near the Khwaja Morad shrine. There is access to all the canyons from the mountain plateau.

The Kal-e Kaneske Canyon was the strongest base at Sharafat Koh. It takes 35-40 minutes to walk from its entrance to the end. The canyon mouth is an opening in solid rock and is only two or three meters wide. When you walk into the canyon, you cannot see the sky above you, but later it widens into a three or four hectare area at the end of the canyon where there are trees. A stream runs intermittently through the canyon. There is even a water fall with a 40 meter drop. The canyon had a water reservoir, a supply dump and 16 caves holding 60 people. We defended the canyon with DShK machine guns on the high ground on both sides of the canyon.

In the early days of the war, the Mujahideen had very strong bases around the province centers of Farah and Nimruz, but later on Soviet/DRA pressure forced them outward from Farah to Sharafat Koh. The Mujahideen had their first base at Sharafat Koh in the Tangirá Canyon in 1979. The Mujahideen were organized into tribal groups and initially the Achakzai, Norzai, Barakzai and Alizai all joined together and moved to a new base in Jare-e Ab Canyon. The Soviets attacked this base in 1980 and the Mujahideen then moved to Kal-e Kaneske Canyon. The Mujahideen had bases within the city of Farah until 1982. As the DRA and Soviets tightened their security around Farah, these Mujahideen moved out and some fell back on Sharafat Koh. After the Mujahideen left Farah, they lost their contact with the city population. The city population was not tribal and looked down on the Mujahideen as rustics. In turn, the Mujahideen looked down on the city dwellers for their easy life.

Sharafat Koh lies about 12 kilometers from Highway 1 and 20 kilometers from Highway 517. We attacked convoys near Karvangah, Charah and Shivan and the Soviets manned posts at Karvangah, Charah and Velamekh to protect the convoys.

In 1982, the Kal-e Kaneske Canyon was our primary base. Our leader was Mawlawi Mohammad Shah from the Achakzai tribe.3 Mohammad Shah liked to brag about his base and would often escort visitors through the canyon. Once he brought a DRA officer into the canyon and gave him a tour. The DRA officer was also an Achakzai and he told Mohammad Shah that he was stationed in Shindand and wanted to establish secret contact with Mohammad Shah and work with him. Evidently, while the DRA officer was in our canyon, he managed to steal a map showing our base defenses.

At noon in July, about a month after the DRA officer’s visit, three Soviet helicopter gunships suddenly flew down the canyon and fired at the caves and structures of our base. Our DShK machine guns were all positioned on the high ground and could not engage aircraft flying below them in the canyon. The gunships were severely damaging our base. Khodai-Rahm was one of the DShK gunners. Physically, he was a weak person, but he took the 34 kilogram (75 pound) weapon off the mount, hoisted it on his shoulder and fired down into the canyon. He hit two of the helicopters, one of them in the rotors. That helicopter gunship climbed to the top of the mountain and then the rotors quit turning. The pilot bailed out, but he was only 50 meters above the mountain and he and the helicopter crashed onto the mountain southern wall near the interior mouth of the canyon. The second damaged helicopter managed to escape, while the third helicopter attacked the Mujahideen DShK gunners. Khodai-Rahm was killed by the third helicopter.

The cheering Mujahideen rushed to the helicopter. There were five dead Soviets—the pilot, two crew members and two passengers. One of the passengers was a woman. One of the Mujahideen cut off the pilot’s head and brought it to Mohammad Shah. Suddenly Soviet fighter-bombers flew over our base and began bombing us. Toward late afternoon, Soviet transport helicopters flew in and landed some three kilometers from the canyon mouth. Soviet troops dismounted and took up blocking positions—presumably to prevent us from taking the downed crew out. Early the next morning, Soviet armored vehicles arrived and surrounded the area. (Map 11-6 -Kaneske 1) Soviet infantry pushed forward, supported by armor. The Soviet infantry moved on the high ground along the Tora Para4 toward the crash site. Some Soviets moved along the canyon floor and the opposite canyon wall, supported by troops on the high ground of Tora Para. As the Soviets advanced, they marked boulders and rocks with numbers for orientation. After seven days of fighting, they reached the helicopter crash site. We retreated to higher ground by the waterfall. On the eighth day, the Soviets left, taking their dead, including the headless torso, with them. They left the hulk of the helicopter behind.

COMMENTARY: One of the more successful Mujahideen air defense ambushes involved digging in heavy machine guns into caves in canyon walls. When the Soviet/DRA helicopters flew down the canyon, the machine guns would fire across the canyon filling the air with bullets. The helicopters could not attack the machine guns and were hard pressed to avoid the bullets. This ambush would have worked well in Kaneske Canyon.

The Soviets painted numbers on boulders and rocks to provide reference points during their attack. This is a good technique as it aids adjusting air and artillery fire and keeping track of the progress of units as they advance. Still, the Soviet attack was a frontal attack which allowed the Mujahideen to concentrate their fires against the Soviet advance.

In March 1983, our group leader, Mawlawi Mohammad Shah, took the bulk of our Mujahideen to Nimruz Province. Iran had supplied him with weapons and encouraged him to join the Mujahideen in Nimruz Province in attacking the DRA 4th Border Guards Brigade at Kang Wolowali (District) near the Iranian border. Along with the Iranian weapons, Mohammad Shah took most of our DShK machine guns. The attack on the border post failed and Mohammad Shah lost 35 men. His own son lost a leg in the fighting. It was a heavy blow to our group and we felt that Iran had conspired in our defeat. At the time, Mohammad Shah was about to form an alliance with the Maoist Gul Mohammad and Parviz Shahriyari. Both were from Harakat (IRMA) and receiving arms from Iran. Under the alliance, we would leave Sharafat Koh and move to Chahar Buriak. This would have strengthened the Mujahideen and Iran wanted to weaken us and make us dependent on Iran. As a result of the disastrous attack, the Sharafat Koh Front was now weakened and we only had 25 men in our base. After the disaster, I was preparing to leave the base and visit my home, but as I moved out I saw that the Soviets were fighting in Shiwan, so I returned to the base where I made radio transmissions supposedly sending 50 men to this ridge and 40 men to that ridge. This radio deception was supposed to keep the Soviets at bay.

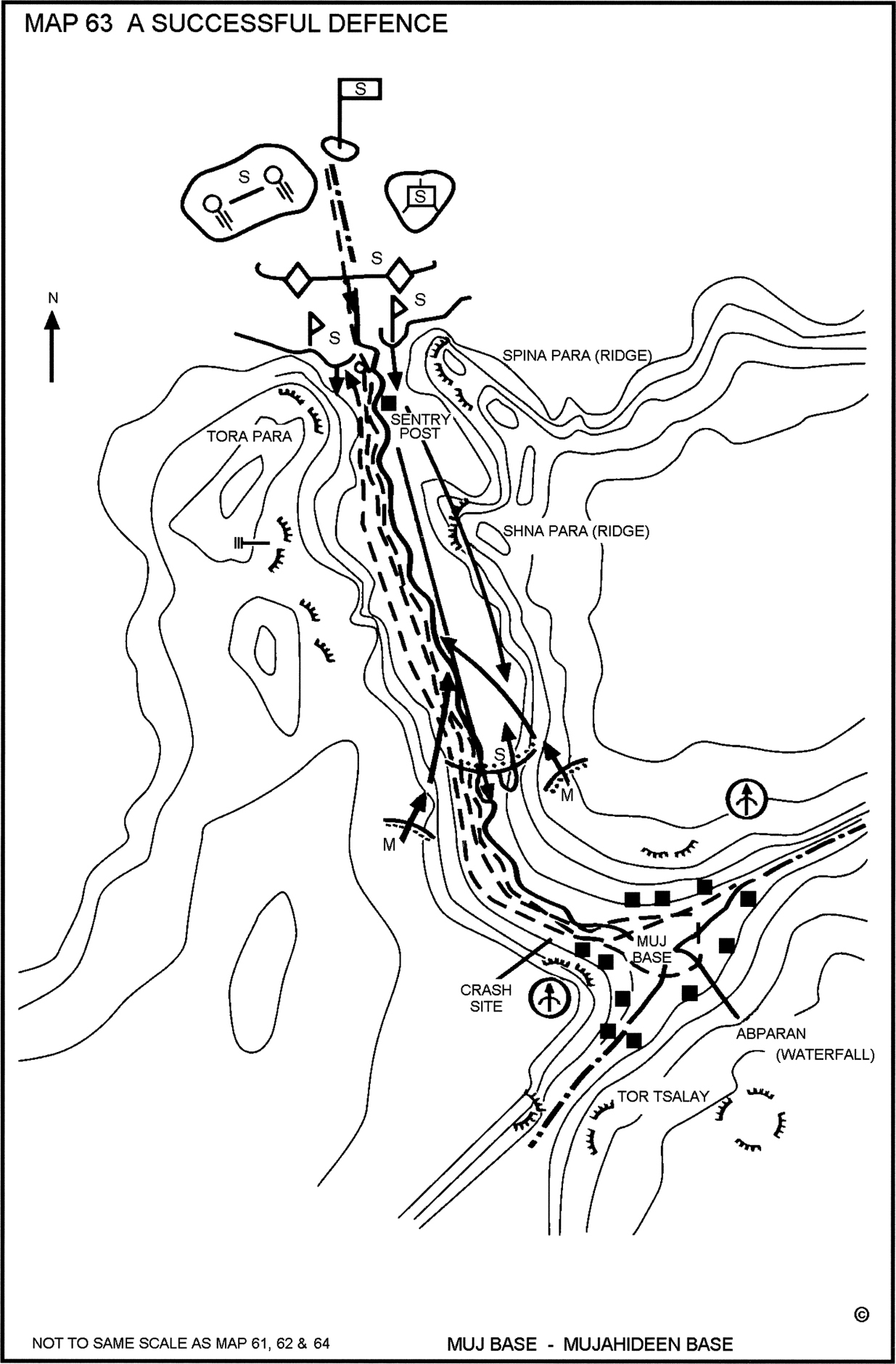

I was sleeping at Nizam Qarawol, the gate security post at the mouth of the canyon, when, early in the morning, we heard a helicopter flying over. (Map 11-7 - Kaneske 2) We put our ears to the ground and heard the noise of tanks approaching. We quickly moved through the darkness to our base, pausing only to lay some antitank mines. Mohammad Shah’s deputy, Haji Nur Ahmad Khairkhaw, was in charge. We had gathered in the darkness discussing what to do when Malek Ghulam Haidar and his Mujahideen from Shiwan joined us. They had noted the Soviet preparations and guessed that we were the target, so they came across the desert to join us. They arrived hours before the Soviets. We vowed to resist and to kill anyone who tried to flee. We took up positions on the high ground on both sides of the canyon on the ridges of Tora Para, Shna Para and Spina Para. We also put five men on the rear approach to the canyon and put some men on Tor Tsalay to watch the approach from Jar-e Ab Canyon. It was raining, but not enough to stop the Soviet aircraft. Observation aircraft flew over and then fighter-bombers flew over in groups of three. They made bombing runs on us. We only had two DShK machine guns left and they were not enough to keep the aircraft away. The enemy intensified his bombing. They also began firing artillery at us and kept it up all night, depriving us of sleep.

Before sunrise on the second day, the enemy ground attack began. There were probably two battalions in the attack. One battalion attacked Tora Para and the other attacked Spina Para. Tanks supported the dismounted infantry, who tried to approach the canyon but failed. During the afternoon of the second day, Malek Ghulam Haidar was killed deep inside the base area. We had several Afghan prisoners in our base, who we detained for disputes and crimes committed in the area controlled by the Mujahideen. A Haji from Zir Koh was one of our prisoners. He described how a lone Soviet came into the camp and pointed his rifle at the prisoners. Through sign language, they indicated that they were prisoners, so the Soviet herded them into the prison cave and stood outside for awhile. Then he disappeared. Nabi, who was carrying food to our front lines returned to the camp and saw the Soviet. Since he was unarmed, he ran and the Soviet followed him. Nabi ran to the arms depot where Malek Haidar was. Nabi told him that Soviets had penetrated the base from the mountain top. Malek took his American G3 rifle and his Soviet TT pistol and walked out of the depot cave. The Soviet was waiting behind a rock. He fired two shots and killed Haidar. Then he took Haidar’s G3 and pistol and left. I was sitting at the first aid station near the front lines when I heard Abdul Hai yell “Who are you? Who are you? Stop!” at the Soviet. Another Mujahideen was going to shoot him, but didn’t since the Soviet was far away and they thought that he might be a prisoner carrying supplies to the forward positions. The Soviet was in uniform, but he was down in the canyon and we were high above him on the canyon walls and couldn’t really tell. Since the Soviet aircraft were still bombing us, we did not believe that a single Soviet had snuck into our base and was now leaving. Timurshah Khan Mu’alim, who was at Shna Para, also aimed at the Soviet, but Bashar, Mohammad Shah’s nephew, talked him out of it, convinced that the stranger was one of our own. Later, we learned that the Soviets had invited some local elders to the attack site to impress them with their strength. The elders later described how the Soviet soldier came running into the site proudly holding his trophy weapons over his head. The Soviets again fired artillery at us all night.

Early on the morning of the third day, the Soviets again attacked. They figured that we had no forces on the canyon floor, so they fired smoke rounds into the canyon. We thought they were using poison gas and tied handkerchiefs over our faces. The Soviets moved into the canyon under the cover of the smoke. At first, we fired blindly into the smoke from the high ground until we saw them signaling each other with flares. We fired at the flares and then realized, from the flares’ positions, that they had penetrated far into the base. The Mujahideen in the base were shouting “The Russians are here!” and firing at close range. We abandoned our positions in the heights and charged down the canyon walls. The fighting was heavy. The Soviets withdrew in the late afternoon, taking their dead and wounded with them. They left blood trails, bloody bandages and many RPG-18s behind. Again, Soviet artillery fired at us all night.

On the fourth day, the Soviets advanced with tanks leading and the infantry sheltering behind the tanks. The infantry was reluctant to leave the shelter of the tanks, but they finally moved into some folds on the canyon wall and sheltered there while the tanks withdrew. The infantry would not move out from the protection of the folds and finally the tanks came forward again and the infantry retreated behind the tanks. At noon, they quit firing and the Soviets broke camp and moved out in the afternoon. We lit bonfires and cheered from the heights. The bonfires were welcome since it had rained throughout the battle and we couldn’t light fires earlier as that would have disclosed our positions.

COMMENTARY: Again the Soviets conducted a frontal attack, but this time relied on a smoke screen to aid their advance. The advance was initially successful, but the Soviets failed to clear their flanks as they advanced. Once the Soviets began to take casualties, they withdrew, abandoning ground they would unsuccessfully try to retake the following day. The Mujahideen, who lacked communications, were hard pressed to control the battle.

In 1985 we had disputes over leadership and distribution of spoils and the Mujahideen split into tribal units and moved into the various canyons. Haji Abdul Kheleq and his Mujahideen from the Noorzai tribe moved to the Shaykh Razi Baba Canyon. Haji Ghulan Rasul Shiwani Rasul Akhundzada and the Mujahideen from the Alizai and Barakzai tribes moved to the Kale-e Amani Canyon. I went with this group. Mawlawi Mohammad Shah and his Mujahideen from the Achakzai tribe stayed in the Kale-e Kaneske Canyon.

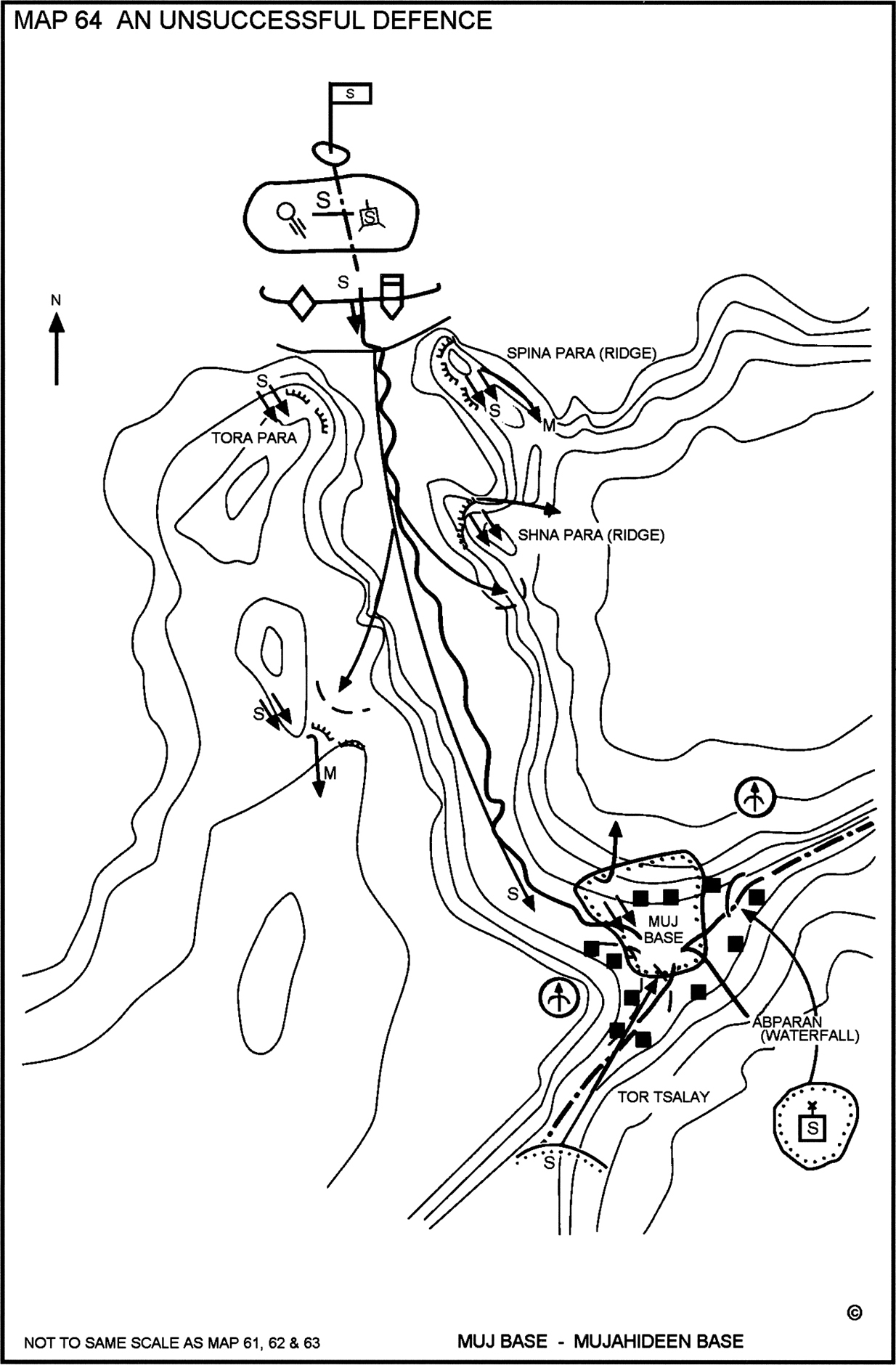

After the groups had moved to the different canyons, the Soviets returned. The Soviets concentrated on Mohammad Shah and his Mujahideen in the Kal-e Kaneske Canyon. He had six DShK machine guns, one ZGU-1 machine gun, three 82mm recoilless rifles, 25 RPG-7s and some medium machine guns. Soviet troop columns with up to 200 tanks and APCs moved from Shindand to Farah and surrounded the area.5 Soviet aircraft flew from Shindand airbase and bombed the base from high and low altitudes. Soviet artillery moved into position and hammered his positions for several hours with heavy fire (Map 11-8 - Kaneske 3). The Soviets spent the first day with artillery and air preparations. On the second day, they launched an attack against the canyon with infantry supported by tanks. Mohammad Shah’s force repulsed the attack. On the third day, the Soviets attacked the canyon mouth again, but they also snuck a force up the Jar-e Ab Canyon and then landed air assault forces on the mountain top. These forces crossed over into the Kal-e Kaneske Canyon and took Mohammad Shah’s force from the rear. Mohammad Shah’s son was killed while firing his ZGU-1. Mohammad Shah’s force was pinned between the two Soviet forces as night fell. Mohammad Shah gathered his force and said “Either we stand and die here to the last man or we take a risk and charge the attackers and try to break out. We should break out as a group. If they see us, we will have enough firepower to fight them. If they don’t see us, we will all leave together.” All his Mujahideen agreed. Some 70 Mujahideen slipped out between the Soviet forces, up the canyon and into the mountain. Only a few old men remained. The next day, the Soviets continued to pound the canyon with air and artillery, not knowing that the Mujahideen had escaped. On the fifth day, they entered the base, mined the caves, looted what they could and left.

The Soviets then turned their attention to Kal-e Amani Canyon. They came across the high ground from Kal-e Kaneske and air assault troops attacked down into the canyon from the high ground. Most of us were unable to escape and we lost some 50 Mujahideen there. The Soviets then turned their attention to Shaykh Razi Baba Canyon, but these Mujahideen had already left. This was the end of the Mujahideen stronghold of Sharafat Koh. We now knew that we could not hold these large bases in Afghanistan indefinitely against the Soviets, so we moved our bases, staging areas and rest areas across the border into Iran.

COMMENTARY: The Mujahideen maintained bases at Sharafat Koh from 1979-1985. It was no secret that they were there and the Soviets and DRA had ample opportunity to work against the base. The Mujahideen were tied to these bases and had to maintain sufficient defenders at Sharafat Koh at all times. This limited the number of Mujahideen who could strike at the Soviets and DRA. Once the Mujahideen split up into several canyons, they lacked communications between the canyons and were unable to provide warning or coordinate actions against the Soviets. The Soviets were able to defeat each group piecemeal.

However, the Soviets were not successful in attacking Sharafat Koh from the desert floor up. It took the Soviets a good deal of time before they would land air assault forces on mountain tops far from link-up forces. Once they started doing so, they were often successful. However, some heliborne forces were isolated and destroyed in the mountains by the Mujahideen. In this case, the Soviets were successful when they used helicopters to land troops on the heights and attack down to link up with ascending forces.

Nimroz Province lies in the southwest corner of Afghanistan. It is fairly flat, lightly populated and mostly desert. The population lives in the green zones along the river banks. The Khash Rud is one of three rivers which run through the province. It runs northeast to southwest. My base was 10 kilometers southwest of the Lowkhai District capital in Khash Rud District. (Map 11-9 - Khash) It is a wooded area at the village of Qala-e Naw near the banks of the Khash Rud River. Highway 606 runs from Delaram and Zaranj—the provincial capital. It parallels the river and used to run through the green zone. We would often block the highway and intercept convoys traveling on it. Sometimes we would attack the provincial capital. I had about 200 men in my main base at Qala-e Naw and had a forward base at the Pul-e Ghurghori bridge, where the highway crossed over the Khash Rud. I often mined and destroyed that bridge to deny passage to columns going to Zaranj. My main base on the river was split between the southeastern and northwestern banks. During flood stage, it was impossible to cross the river and the Mujahideen on each bank fought in different regions throughout the year. Later in the mid-1980s, when our resistance became very costly to the enemy, they built a detour route on the plain between Zaranj and Delaram. This detour arched about nine kilometers away from my base. When the detour route was built, I could only field reduced groups of 15-20 men against small enemy columns since the area is very arid, very open and water supply is a major problem. We had to let the big convoys pass unmolested. The new road rejoins the old at the village of Radzay. This is about 17 kilometers to the southwest. I started moving our ambushes to the Radzay area. There is a mountain to the east of Radzay with the same name. The road crosses behind the mountain on the southeast side. This is an excellent ambush site since there are also hills which restrict movement to the road as it goes between the hills and the mountain.

In the fall of 1984, Khan Mohammad (my deputy) and I were both away from our base at the same time. I was in Iran. Informants told the government that we were both away and so the government attacked our base in our absence. However, the day that the enemy forces attacked our base, Khan Mohammad returned to our base. It was five days before the feast of sacrifice (Eid-al-Adha). The enemy moved from Delaram to the plain some 15 kilometers north of us—just north of the main road. They established a base there. Since it is desert, they could move in any direction. They attacked our base the next day. There were only 70 or 80 Mujahideen in base at the time. Our SOP for defense against an attack was to spread the forces over a large area at strong points in some 20 villages. The enemy would usually attack from the northeast to the southwest through the green zone to the base area. He would also send a flanking detachment to the Pul-e Ghurghori bridge and lodge in the Radzay Mountain to encircle my force and pin us in the green zone. My force had to fight in the green zone because the surrounding desert was too flat and exposed for combat. We fought the enemy in the green zone by confronting him with multiple pockets of resistance anchored in fortified fighting positions. When the enemy tried to concentrate against one pocket, Mujahideen from the other pockets would take him in the flanks and rear. The enemy could not fragment his force to deal with all the pockets, but had to stay together for security. We would let the enemy chase us from strongpoint to strongpoint and attack him whenever we could. Eventually, the enemy force would become exhausted. When their water and supplies ran out, they would break contact and go home.

The enemy attack developed as usual and, by the end of the day, the enemy force retired. Unfortunately, my deputy was killed during the fighting. In Iran, I heard about the enemy attack, gathered what Mujahideen were available and started back to our base. The Mujahideen at the base evacuated their casualties to Qala-e Naw, Sheshaveh and Radzay. Informants told the enemy that the base commander was killed. They thought that I was dead and decided that it was the time to destroy all the Mujahideen in the green zone. I arrived on the third day after the opening battle. That night, another enemy column arrived and deployed in the desert north of us. I realized that they were going to attack us. We had one BM-12, one single-barreled 107mm rocket launcher, six 82mm recoilless rifles, five DShKs, three ZGU-1s, and 15 RPG-7s. I now had 120 men. In addition to my Mujahideen, there were HIH Mujahideen in the area and they helped defend the base camp area. I sent 20 of my men to the Ghurghori bridge with four RPG-7s and Kalashnikovs. I told their commander to put 10 men on each bank to block the enemy tanks which would make the encircling sweep. However, that group didn’t reach the bridge on time. They stopped short of the bridge to avoid falling into an ambush. The enemy seized control of the bridge at dawn. His other groups deployed at Qala-e Naw, Radzay, Sheshaveh and other points in the area.

The enemy attacked, as usual, from the northeast and southwest. The main attack was from the northeast and involved some 150-200 vehicles. My bridge group attacked the enemy group at the bridge, but the enemy pushed them back and began advancing toward the northeast from Radzay. Six enemy jet aircraft were attacking our positions, while four helicopters adjusted their strikes for them. The helicopters fired smoke rockets to mark the strikes. The fighting continued for two days. Then they broke contact and withdrew. During the fighting, 16 DRA soldiers defected to us. They were soldiers drafted from Farah and Nimroz Provinces. They were from the 21st Mechanized Brigade in Farah and the Sarandoy regiment in Nimroz. There were also DRA deserters from the 4th Border Guards Brigade. Mujahideen casualties were three KIA and several wounded. Enemy losses are unknown except for the 16 deserters.

COMMENTARY: When asked what made him successful Commander Baloch said, “We intended to fight to the last man and they didn’t. This is a wide area and we were widely dispersed, which reduced the impact of the enemy air force. Air power was fairly ineffective in this desert. Many of their bombs failed to explode, but buried themselves in the sand. We had covered shelters and covered fighting positions in each village. The enemy was very stylized and never did anything different. We knew from where they would come, how they would act and how long they could stay. Our defensive positions were connected with communications trenches while the enemy was always in the open. We had two kinds of maneuver. One was the dispersal maneuver forcing the enemy to chase all over to find us. The second was internal maneuver within a strong point where we could shift between positions without being observed. We had these positions in all the villages and throughout the area. There are also many canals and ditches in the area, which we improved into fighting positions.”

“Once the enemy offered me a deal. ’Don’t attack us and we will pay you a toll of 50,000 Afghanis ($250) per vehicle passing through the area.’ I turned the deal down with the words ’As long as Soviets are here, we make no deals.’ The enemy infantry was the weakest part of their armies—DRA and Soviet. Their sequence of attack was very predictable. They would start with an artillery and air preparation, then they would lay a smoke screen and then their infantry would attack. Their tanks would support the infantry, but as soon as they sustained casualties, they would stop. Their tanks were very wary of antitank weapons. The mere presence of RPGs and recoilless rifles in an area would keep the tanks at bay. We would wait until tanks came within 20 or 30 meters of our antitank weapons before opening fire. I would not allow my people to try long-range shots. They would hold steady in their positions with patience and courage. The tanks could not see us at long range so they couldn’t hit us. We could see them and hit them at close range. Most of the time we were fighting an enemy strong in fire power and very weak in the assault. During the two days of fighting, the enemy seldom came within Kalashnikov range. The only innovation that the enemy showed during this attack was that they launched it during the Festival of Sacrifice, when they expected that the Mujahideen would be at home instead of the base. Second, they returned sooner to the area than usual. This broke their pattern. I did not really fight a guerrilla war—I knew the enemy’s position and he knew mine. A guerrilla is evasive and attacks from an unexpected direction and time. Here, the enemy kept attacking me at the same place and in the same fashion. Is this guerrilla war?”

“Our ambulance was two sticks and a piece of cloth. Theirs was a helicopter. The secret of our success was that it was a popular cause. Everybody knew that we were hurting the occupiers. This was not a war but an uprising. Therefore, it was not a guerrilla war. We never bothered about the food supply. The locals supplied us with whatever they had. I had two pickup trucks—the enemy had two hundred vehicles. I used the pickups for ammunition and food resupply. We moved them secretly along the river in the wooded area to supply the fighting positions in the evening. Their rations would sustain them until the next night. We basically had a mutton and nan6 diet that the local populace furnished us free. A normal full day’s ration was a portion of cooked mutton wrapped in nan. Water supply was simple since our fighting positions were near the river and my men all had canteens.”

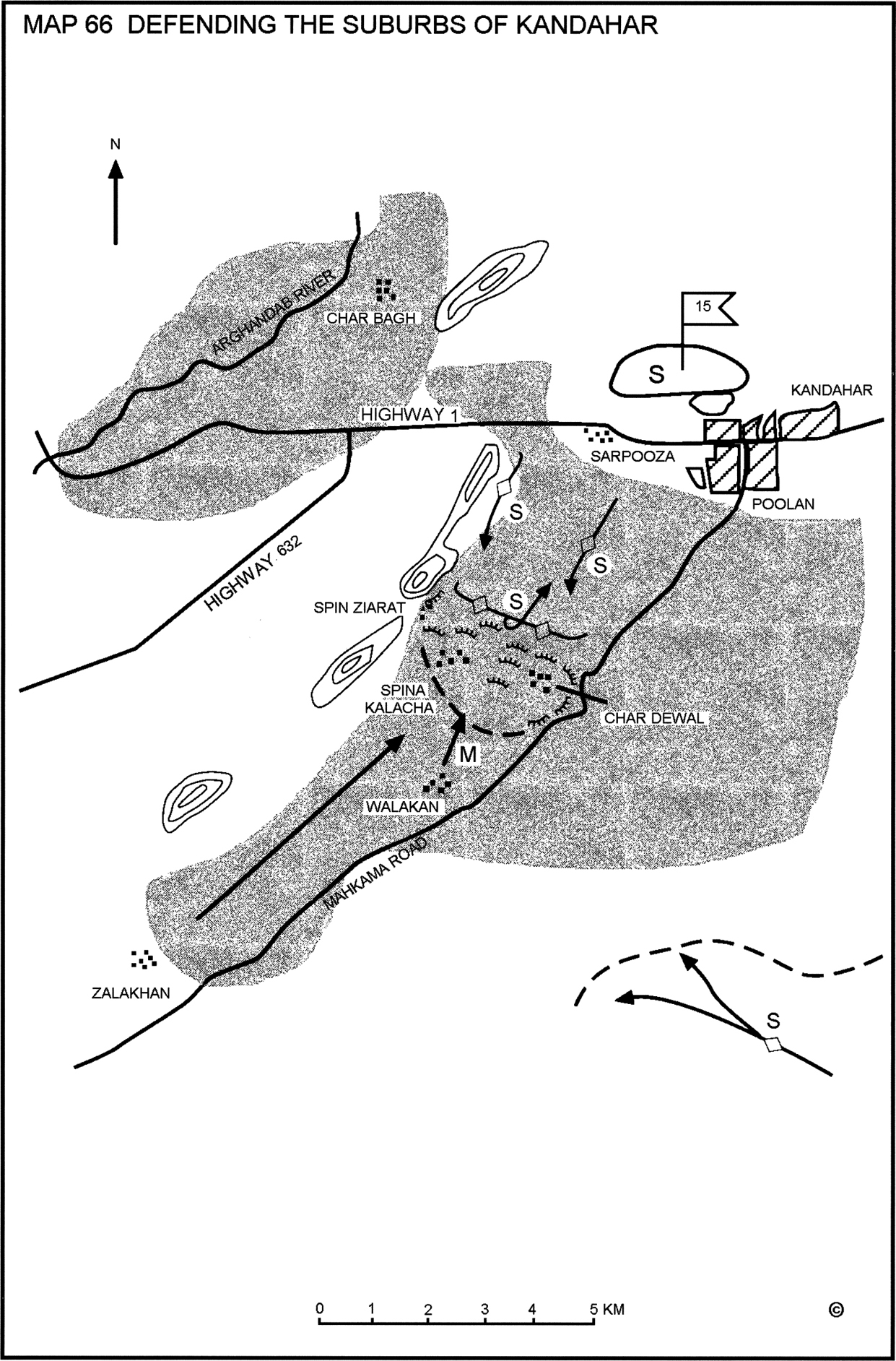

The supporters of the HI faction, mostly Shia, were located primarily in the southwest of Afghanistan. The HI’s main base was in the Khakrez southern mountains. This base was near the HIK base of Islam Dara.7 This was about seven hours on foot from Khakrez, which is some 60 kilometers north of Kandahar. The HI fought in Khakrez, Girishk, Uruzgan and Kandahar. The HI faction had four units in the Kandahar area. We had about 300 Mujahideen. Our overall commander was Ali Yawar who was killed by a mine later in the war. We had two bases in the Kandahar area—Char Dewal in the Malajat suburbs south of Kandahar and Char Bagh in the Arghandab River Valley northwest of Kandahar. I commanded a group at Char Dewal as did Ghulam Shah and Shah Mohammad. Gul Mohammad commanded at Char Bagh. We used to harass convoys and block Highway 1 near the Kandahar prison at Pashtoon Bagh—about a half kilometer from the Sarpooza ridge. Unlike some other areas in Afghanistan, all the Mujahideen factions cooperated with each other in the Kandahar area. Whenever there was any fighting, all the Mujahideen would move to the area to help out. All large Mujahideen operations were combined and were coordinated by the Mujahideen Council.

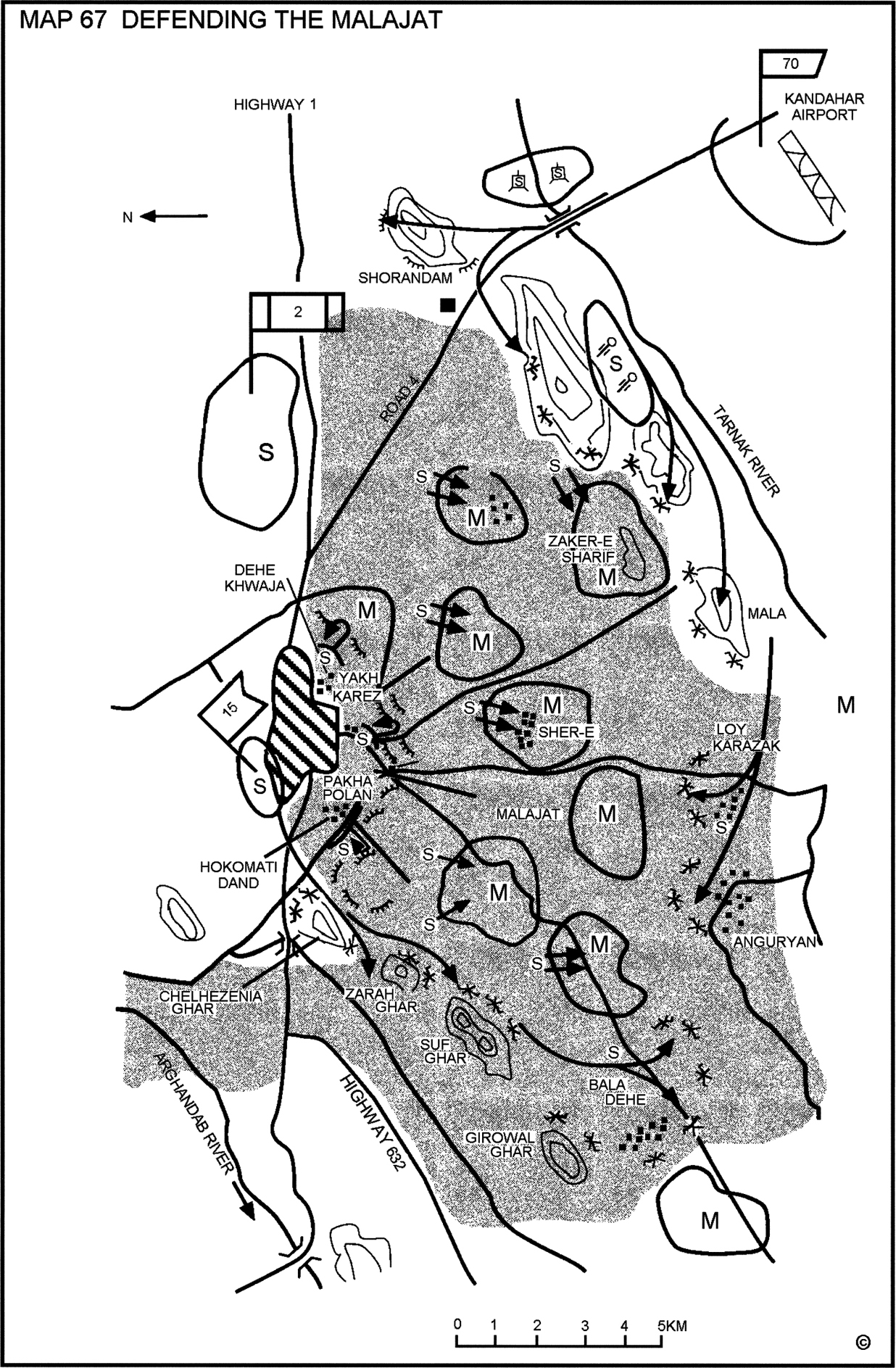

The Malajat area lies to the south of Kandahar. It is a well-irrigated suburb of the city full of villages, irrigation canals, orchards, farms and vineyards. The Mujahideen moved freely throughout this area despite the best efforts of the DRA and the Soviet forces in the area.8 Frequently, the DRA and Soviets would throw a cordon around the Malajat area and try to enter it to destroy the Mujahideen and their bases. Throughout the war, these efforts never succeeded. There were always at least 1,000-1,500 Mujahideen in Malajat from the various factions. These Mujahideen were all from mobile groups and none were stationed permanently in Malajat. Mujahideen forces would rotate in and out of the Malajat area and thus maintained a high state of readiness. The Malajat mujahideen were well prepared with supply bases and well-fortified bunkers and fighting positions (Map 11-10 - Malajat).

In the fall of 1984, the enemy threw a wide cordon around the Malajat occupying their normal southern positions from Zaker Ghar in the east to Qaitul in the west. Thus they surrounded the Malajat with Kandahar to the north and Highway 4 to the east and a ridge of hills to the west. This encompasses a lot of space and the Mujahideen were still able to maneuver freely within the Malajat area. At 0700 hours, an enemy mechanized column of 30-35 tanks and APCs moved from Sarpooza while another column of 15-16 tanks and APCs moved from the 15th Division headquarters past the Governor’s house along the Mahkama road near Poolan toward our defensive position. Our defensive position stretched some three kilometers from Char Dewal to Spin Ziarat and we could always see the enemy defenses from here. We held this position with some 450 Mujahideen from various factions. There were HIK units from Sarkateb, the Gulagha Son of Haji Latif’s unit and two of our HI groups. The enemy columns were covered by helicopter gunships who fired at our positions. However, the enemy was unable to advance because we were well-protected by our defensive positions. The enemy would not dismount from his armored vehicles, but deployed his vehicles in a firing line and fired at us for two or three hours. Even the green trees caught on fire. Our defensive positions were three meter by two meter pits which held two-to-three men. They were roofed with heavy wooden beams which had 1.5 meters of dirt and rock tamped down on top of it. During lulls in the enemy firing, our men would pop out of the shelters and fire RPG-7s and recoilless rifles at them. The enemy would promptly start shooting again.

I said that the Soviets surrounded us, but that isn’t completely true. Throughout the war, the Soviets always left one side unguarded. At around noon, 100 to 120 Mujahideen reinforcements arrived from Zalakhan and Walakan, which are south and southeast of Spin Zirat. These villages were in the sector that the Soviets left unguarded. The arrival of the reinforcements turned the tide and eventually prompted the Soviets to withdraw about 1800 hours. We destroyed three armored vehicles on the Sarpooza front and two on the Mahkama front.

Sometimes the bombs and artillery fire would block the exits to our bunkers. We would have to go out at night to dig them out. This happened often to our positions near the Panjao Pul bridge. Three times I had to go out at midnight to locate the bunkers and unearth our men. Sometimes they would be trapped in these bunkers from 0500 hours until past midnight, but these bunkers were essential to stopping the enemy in the Malajat.

COMMENTARY: Soviet cordon and search operations usually involved a large force surrounding a large area. The area contained within the cordon was usually large enough to allow the surrounded Mujahideen freedom of maneuver. Once the cordon was established, the Soviets seldom split it up into manageable areas, but pushed through the entire cordoned area if possible. This failure to fragment the area allowed the Mujahideen to move and maneuver against the Soviets. In this case, the Mujahideen were able to reinforce during a hotly contested fight.

Many Soviet combat examples show an unguarded flank in a cordon and search.9 This might work if an ambush were set along the escape route, but this did not seem to be the case. This might also be a time-honored act to allow their enemy to escape and minimize the casualties on both sides.

Finally, there was an apparent reluctance by the Soviets and DRA to stay in the Malajat area at night. If they would not dismount from their armored vehicles during the day, they would have to dismount at night to secure the vehicles. The arrival of the Mujahideen reinforcements may have kept the Mujahideen in the fight, but may not have been the prime reason that the Soviets withdrew at 1800 hours.

The Malajat, the southern suburb of Kandahar, was a continuous battlefield. The Malajat is a large green zone full of orchards, villages, irrigation canals, and vineyards. The Mujahideen deployed mobile bases throughout it. Many Mujahideen commanders with bases elsewhere would maintain mobile bases in the Malajat as their forward elements in the Kandahar area. Despite belonging to different factions, there was an exemplary cooperation among these mobile groups. The DRA/Soviets tried to force the Mujahideen out by cordon and search operations of the Malajat area. They would occupy the high ground and villages north of the Tarnak River—Shorandam, Zaker-e Sharif, Loy Karazak, Anguryan, and Bala Deh which are north and west of the airfield. Then they would establish the western blocking positions on the Girowal Ghar, Suf Ghar, Zarah Ghar and Chehelzena Ghar mountains (Map 11-11 - Mala). They used the city of Kandahar as the northern blocking position. Kandahar was occupied by DRA forces. Then the Soviets and DRA would push inward into the Malajat area from these blocking positions search for the Mujahideen. They were usually unsuccessful, but they continued to do it over and over again. The blocking positions were also part of the Kandahar security belt, but it was well-penetrated by the Mujahideen. We would fight them initially in the Malajat area and then exit to the south in the Loy Karazak area and Anguryan and in the southwest in the Hendu Kalacha area. The Soviets had trouble controlling these areas.

The Mujahideen prepared blocking positions along major axes and turned this area into an impregnable stronghold. A typical blocking position would be built near a mobile base and include several buildings in a village or orchard, where the mobile group would live. The personnel in the mobile group would be relieved and replaced from time to time from their main bases. Some Mujahideen would stay permanently in the Malajat area. Mobile bases and blocking positions were connected by communications trenches. The blocking positions were dug into the ground and had firing positions for machine guns, recoilless rifles, and RPGs. We covered the fighting positions with berry-tree branches which we then covered with earth and packed it down hard. The bases had covered bunkers to protect our Mujahideen from artillery fire and air strikes. These bunkers were two-three meters in width and six to eight meters long and were covered with timber and a meter-thick layer of well-packed earth which resisted artillery fire and most air strikes. Whenever the enemy would cordon off the Malajat area and launch infantry attacks into the green zone, the Mujahideen would occupy their blocking positions. Most fighting positions were redundant so that the loss of a fighting position would not adversely affect the defense.

In the beginning, the Mujahideen were unprepared and unable to resist beyond two or three days but, after they developed their fortifications, they could withstand and push back the Soviets and DRA. Once the area was cordoned, the Soviets usually launched their attack along the main road from Zaker-e Sharif and further south from Loy Karazak. In the north, the usual line of contact was Hokomati Dand, Pakha Polan, Yakh Karez and Deh Khwaja. This was just outside the built-up area. Later on, the Soviet and DRA forces established permanent, well-fortified and well-protected security outposts. The Soviets had Shorandam hill, Zaker-e Sharif hill and Mala Kala hill. The DRA had Suf Ghar, Zarah Shar Ghar and Chehelzena Ghar mountain sites. Once every two months, the Soviets would launch a major cordon and search against the Malajat area in order to keep it contained.

In November 1987, the Soviets launched an 18-day cordon and search operation. In the cold dawn, the Soviet and DRA troops moved from their garrisons and, by 0800 hours, had occupied their normal blocking positions. Mohammad Shah Kako’s base was at Sher-e Surkh where he commanded some 30 men. There were some 350 Mujahideen in the Malajat area from his party. The Mujahideen divided the front line facing western Kandahar into four sectors. Each sector had about 50 men. The northwest sector was a Hizbe-Islami sector. The Pakha Polan area was held by Mujahideen from Sher-e Surkh, Zaker-e Sharif and Kukhabad. This meant that Mohammad Shah Kako’s sector had three commanders since there were three factions involved, but cooperation among the commanders was easy since they were all local and knew each other. Regi was the third sector and Abdul Razak commanded this sector. Yakh Karez was the fourth sector and Saranwal commanded it. Ghafur Jan coordinated the four sectors. The DRA attacked from the city, but this time the Soviets did not move from their blocking positions. The DRA infantry were accompanied by troops carrying chain saws. They planned to cut their way through the orchards, destroy them and deny this refuge to the Mujahideen. We had planted mines in front of our positions which deterred the poorly-trained DRA soldiers. We maintained a steady fire from well-situated positions. We kept a reserve of 160-200 men in reserve resting. Every evening, the relief group would move forward, carrying rations and relieve the force who would go back and rest for two days. Then they would rotate forward again. It was usually calm at night when we carried out the relief. In this manner, we kept up the defense for 18 days. We did not resupply during the day, but brought food, water and ammunition forward only at night. The DRA could not break through, but they did cut some trees before we shot them down. It was winter and it was cold. Our positions were good, although resupply was tough. Throughout the fighting, the enemy bombed and shelled all suspected bases in the area. One bomb, intended for our position in Pakha Polan, missed the target and hit the western city gate, killing many civilians. They could not hit us at the front line positions because we were so close to their line and so our front line was safe from air and artillery attack.

COMMENTARY: Throughout the war, the Soviets and DRA were never able to bring Kandahar under complete control. Mujahideen urban groups fought sporadic battles within the city walls and Mujahideen mobile groups maintained control over the suburbs. Unlike other areas of Afghanistan, there was little in-fighting among the factions involved in the fighting around Kandahar and the Mujahideen ran the fight cooperatively through regular meetings of a coordination council. This cooperation provided tactical flexibility to the Mujahideen and their redundant fortifications ensured that Soviet/DRA offensives would never progress far. Most notable is the regular rotation of Mujahideen from the forward positions. A relief in place is a difficult procedure for the best-trained troops. The Mujahideen routinely relieved front-line forces without a loss in combat effectiveness. This is very impressive for any force, and even more so for a force that is in direct contact and is heavily outgunned and poorly supplied.

There was a significant DRA/Soviet force garrisoned in the area. The DRA 2nd Corps, 15th Infantry Division, 7th Tank Brigade, 3rd Border Guard Brigade garrisoned Kandahar city. The Soviet 70th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade, the DRA 366th Fighter Regiment, the DRA 379th Separate Bombing Squadron and a Soviet Spetsnaz battalion garrisoned the Kandahar international airport. The DRA/Soviet operations in the Malajat area were very predictable by time and location. They continually tried to penetrate and sweep the entire area instead of cordoning off and sweeping a smaller section thoroughly. Although the combat in the Malajat area was a fight through a fortified area, the DRA/Soviets continued to treat it as a penetration and exploitation rather than a systematic reduction. DRA/Soviet tactical intelligence apparently did not pick up the pattern in Mujahideen resupply and relief activities to exploit it.

During the Soviet occupation, the eastern bank of the Arghandab River near Kandahar city was a safe haven and the Mujahideen would not fight in this area. The west bank was Mujahideen territory. I had my base in Babur village in the orchards of the west bank (later, after the Soviets withdrew, I established east bank bases in Baba Valisaheb village, Pir-e Paymal and in the western suburbs of Kandahar). My senior commander was Mulla Naqib. During the Soviet occupation, he had a remote base in Khakrez mountain, but his main base was in Chaharqulba village. My eldest brother was killed in fighting at this village base. My next oldest brother fought out of the Babur base and became a commander when my oldest brother was killed. Commanders were selected based on the social position of the family, education, and personal leadership talents. Family ties were important. A commander brought his relatives into the group and a prestigious family could raise a large group. Since my brother established the group, it was natural that my brother, and, subsequently, I should succeed to the command. In fundamentalist Mujahideen groups, commanders were picked for ideological commitment and not for family ties. Many teenagers joined the Mujahideen because the DRA would press-gang youth into the army and Mujahideen bases were a good place to avoid the draft.

In June 1987, during the month of Ramadan, the DRA/Soviets launched a major operation in the Arghandab (Map 11-12 - Chahar). During the operation, the enemy concentrated in Nagahan and then moved northeast along the western bank of the Arghandab River. Another column crossed the Arghandab River from Baba Valisaheb. They began with a heavy air attack against suspected Mujahideen bases. We moved to our bunkers. The west bank was actually a Mujahideen fortified zone, which we laced with bunkers, fighting positions and trenches. Further, since the green zone was full of orchards, it was already cut up by irrigation ditches, so there was always a place to fight from. We did not leave the bunkers since we were pinned by all the aviation ordnance. Usually, the Soviets would deploy tanks along the edge of the green zone and, after the heavy artillery bombardment and tank fires, they would send infantry (usually DRA) into the green zone with instructions to collect our weapons since everyone in the impact area would be dead. The infantry would move out confidently and the Mujahideen would come out of their bunkers. The Mujahideen would inflict heavy losses on the infantry and capture many of these ill-trained DRA recruits. We sent the prisoners north through the mountains and then, by circuitous routes, south into Pakistan. We had built a veritable fortress around the base at Chaharqulba. Some Mujahideen would defend the bases, while others would range further afield to provide maneuver and depth to the battlefield. It was very hard to move tanks into the green zone. The Soviets would try to push tanks into the area to get close to the Mujahideen, but the terrain channelized their movement and made them vulnerable.

The Soviets and DRA moved from two directions against the Mujahideen but were met with constant resistance from Mujahideen fighting positions. Soviet tanks came from the Zhare Dashta and stayed on the plain west of the green zone as they crept toward our base at Chaharqulba. It took them a week of fighting to cover the six kilometers to our base. All of their tanks were sandbagged against our RPGs, so we were having difficulty stopping them. Finally, we Mujahideen commanders went to Naqib and said that we are outnumbered and should leave the base. Naqib said that this is their last battle and will decide the contest between them and us. They’ve tried to conquer the base for years and this is their last throw. If we leave, we will never get in again. If we stop them, then they will not return. We replied that the RPGs were not working against sandbagged tanks. Naqib took an RPG and strode out to the forward positions to kill a tank. We commanders stopped him and promised to fight to the end.

Heavy fighting continued throughout that day, but we stopped the enemy and they withdrew to Ta’bils—some kilometers to the south. We pursued them to Ta’bils, engaging the enemy in the streets, killing many of them. The Mujahideen then withdrew to Chaharqulba before dawn. The following days, the enemy mounted a three-pronged attack from Ta’bils in southwest, from Baba Valisaheb in the southeast and from Jelawor in the northwest. They employed tanks and artillery on the plain of Zhare Dashta in support. Since the orchards were impenetrable to their tanks, their tanks supported their infantry like naval gunfire from ships. Their tanks would wait until their infantry closed with our base and then would edge into the channelized approaches. As soon as their infantry fell back, the tanks would fall back. Tanks are of little value in the green zone and would seldom advance there. APCs, however, would advance in infantry support. However, their movement was also very channelized and they were easy to attack on the flank.

The enemy would precede his attack with heavy air and artillery bombardment. The Mujahideen would stay in their bunkers to survive and only leave a few observers in the fighting positions. As soon as the observers saw the enemy approach, the Mujahideen would come out of their bunkers and man the fighting positions. The enemy infantry would suffer casualties and then fall back. Many of the DRA soldiers defected. We would broadcast over megaphones “We are not your enemy. We are your brothers. Join us.” Still, the enemy infantry eventually gathered strength and returned to attack our base from the south and southeast and then closed from Jelawor.

Our defenses were vulnerable in the northwest. After continuous fighting, our Mujahideen were having trouble staying awake. At one fighting position, a DRA patrol penetrated the position and stole a recoilless rifle. The gunner was asleep. Commander Ahmadullah Jan saw them taking the recoilless rifle and followed them. Some 25-30 meters away, two APCs were waiting for the DRA patrol. Before they reached their APCs, Ahmadullah Jan and his men, plus another Mujahideen group, intercepted them and fought a fire fight. They destroyed one APC, recovered the recoilless rifle, captured the patrol and captured the remaining APC. They brought the patrol leader, a DRA lieutenant, to Mulla Naqib. Naqib told him “We don’t want to kill you, but tell your fellows that we will not leave and this will mean death for more of you. Stop your attacks and return to your barracks.” The lieutenant replied, “I can’t do this because my family is in Kabul.” We let him go anyway that evening.

The fighting continued for 34 days. During the 34 days, a routine emerged. The enemy would begin the morning with an aircraft and artillery bombardment from the south and southeast. Usually, they would then send eight helicopter gunships to work over the area. Then, they would launch infantry attacks. The Mujahideen would emerge from their bunkers, occupy fighting positions and wait for the approaching infantry. We were hard to see since we had excellent fighting positions and wore garlands of grapevines as camouflage. We let the enemy get closer than ten meters to us before opening fire. We let them get this close for two reasons. First, we wanted to be sure to get them with the first shot. Second, we wanted to prevent their escape. We laid thousands of PMN mines10 in the area—particularly on the infantry approaches from Jelawor. After DRA attacks failed, they would often run into the mines as they tried to escape. The enemy would retreat and we would go out and collect their weapons, rations and ammunition. If the enemy was not attacking us, we would send out ambush parties to hit his columns on the main road. It was usually quiet at night. Sometimes the enemy would fire artillery and bomb us at night but would never attack at night. They did not know their way around the area in the dark, so they did not attempt any night combat.

The DRA had a district government post and local militia on the east bank. We Mujahideen had our families and R&R11 facilities on the east bank since the government would not bomb that area. Supplies came from our homes on the other side of the river, but during heavy fighting, they could not supply us and we were on our own. We could not cook since the enemy would shell any smoke they saw. We had plenty of ammunition since the base was well-supplied and we could resupply ammunition to our positions readily. Food, however, was a serious problem although the number of combatants at the Chaharqulba base did not exceed 500 Mujahideen at any time. The intensity of fire sometimes prevented us from eating during the day—and sometimes even during the night. Sometimes we would salvage rations left behind by the Soviets and DRA. The Soviets would leave lots of food behind, particularly bread. Often our sole rations would be Soviet bread soaked in water.

We also had a problem with treating the wounded. We had medics who had graduated from a short course in Pakistan and were qualified to perform basic first aid. We normally evacuated our wounded to Pakistan for treatment and recovery. During the siege, however, we could not send our wounded to Pakistan. We could not remove the shrapnel and so many of our seriously wounded died of their wounds. We had a few Arabs in our base at this time. They were there for Jihad credit and to see the fighting. “If you are Muslims, help us collect the wounded,” we would tell them. They would refuse.

Except for the Ta’bils offensive and ambushes, we were defending. The Soviets were there in strength, but they stayed on the plain with their tanks and artillery and seldom committed their own infantry. Their tanks and artillery blackened the plain. It seemed that they must have had a thousand of them, but they just stayed there. The DRA infantry was doing most of the attacking and dying. The fight bled the DRA to the point where they could not take any more casualties. Finally, after 34 days of fighting, the enemy forces broke contact at 1100 hours and withdrew. In the past, the enemy had tried to take us, but never had he come in such force or stayed for so long.

We lost up to 60 Mujahideen and commanders KIA in the base and many others in areas around the base. DRA and Soviet casualties are unknown, but we were always catching the enemy in surprise attacks, so his casualties must have been much higher than ours. DRA casualties were definitely higher than Soviet casualties. I feel that the enemy finally quit due to his casualties.12

COMMENTARY: The Soviets used the conscript DRA infantry extensively and supported them with artillery and air power. The DRA infantry was poorly trained and equipped and had serious morale problems. The use of DRA forces as “throw-away” infantry did nothing to increase morale. DRA forces had a reputation for passivity on the battlefield and deserting at the first opportunity.

The Mujahideen defenses were relatively weak from the Jelawor direction, but the Soviets apparently did not push hard enough on this axis to discover this. Soviet and DRA tactical intelligence efforts appear inadequate.

The Soviet/DRA willingness to drag combat out for 34 days and then break contact and withdraw is remarkable. Their refusal to push for quicker resolution strengthened the Mujahideen hand and gradually created a qualitative change in the situation to the Mujahideen advantage. On the other hand, the fragmented nature of the Mujahideen resistance meant that the Mujahideen in Chaharqulba fought in isolation, bearing the full force of whatever the Soviets and DRA could muster. Outside Mujahideen assistance in the form of ambushes against supply convoys and raids on the forces in Nagahan and on the Zhare Dashte plain would have clearly eased the pressure on the Chaharqulba Mujahideen, but there was little operational and strategic cooperation and coordination among the various Mujahideen factions. The Mujahideen factions in Kandahar cooperated better than elsewhere, but as this vignette shows, this cooperation was still limited.

The Mujahideen were quick to pursue a retreating enemy and their offensive into Ta’bils is a good example. Unless a force has established a strong, cohesive rear guard, it is disorganized during withdrawal and unable to concentrate combat power. This instant transition to pursuit was characteristic of the Afghans when fighting the British earlier this century and last.

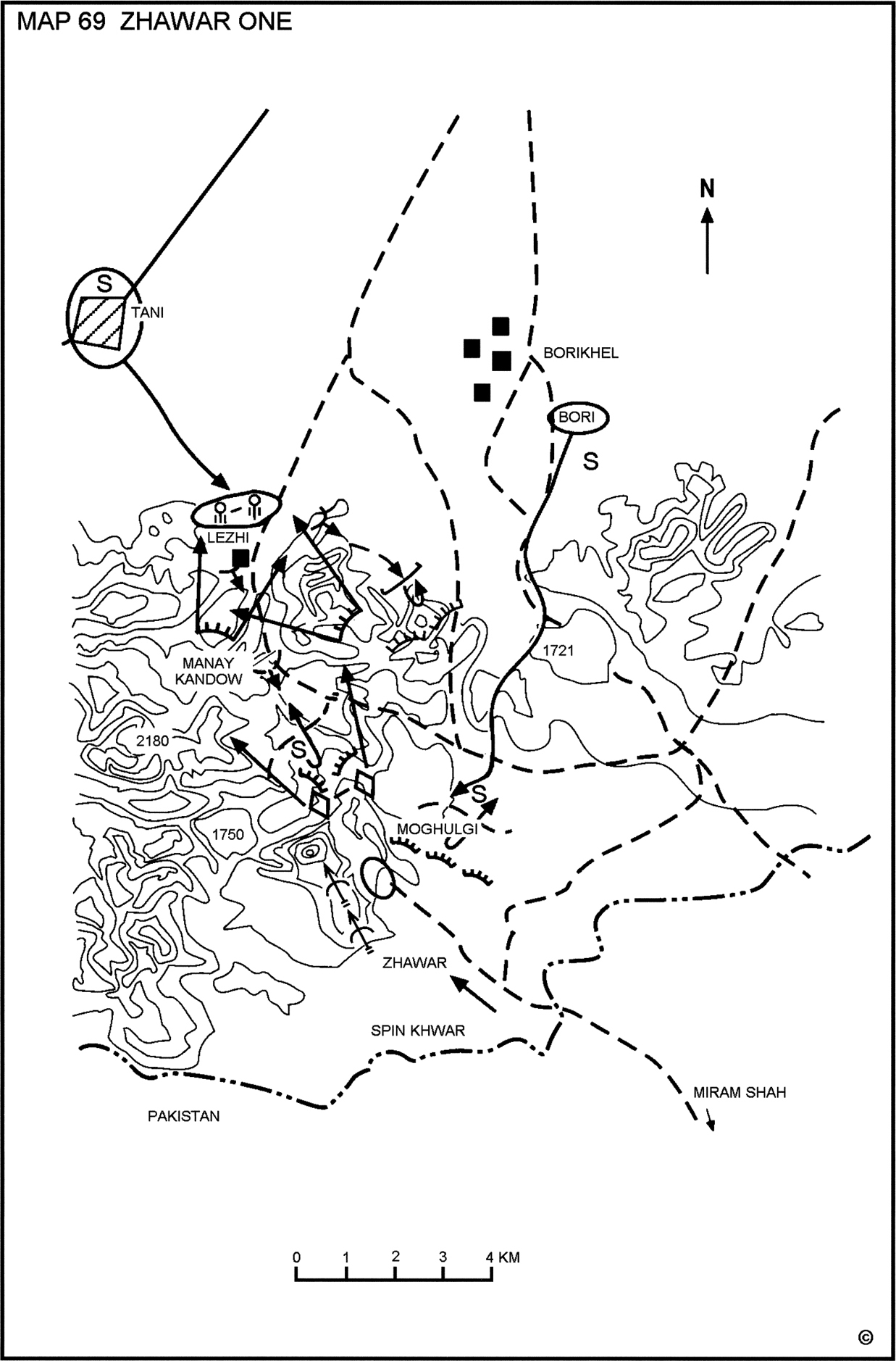

Zhawar was a Mujahideen base in Paktia Province located some four kilometers from the Pakistan border. A 15-kilometer road goes from Zhawar to the major Pakistani forward supply base at Miram Shah. Zhawar began as a Mujahideen training center and expanded into a major Mujahideen combat base for supply, training and staging. As the base expanded, Mujahideen used bulldozers and explosives to dig at least 11 tunnels into the south-east facing ridge of Sodyaki Ghar Mountain. These huge tunnels stretched to 500 meters and contained a hotel, a mosque, arms depots and repair shops, a garage, a medical point, a radio center and a kitchen. A gasoline generator even provided power to the tunnels and the hotel’s video player! This impressive base became a mandatory stop for visiting journalists, congressmen and other “war tourists.” Apparently, this construction effort also often interfered with basic construction of fighting positions and field fortifications. The Mujahideen “Zhawar Regiment,” some 500 strong, was permanently based there. This regiment was primarily responsible for logistics support of the mobile groups fighting in the area and for supplying the Islamic Party (HIK) groups in other provinces of Afghanistan. Due to the primary logistics function, the regiment was not fully equipped for combat, but was a credible combat force. The regiment was responsible for local defense and for blocking infiltration of Khad and KGB agents between Afghanistan and Pakistan. They manned checkpoints along the road to screen identification papers. The regiment had a Soviet D30 122mm howitzer, two tanks (captured from the DRA post at Bari in 1983), some six-barrel Chinese-manufactured BM-12 MRL and some machine guns and small arms. A Mujahideen air defense company also defended Zhawar with five ZPU-1 and four ZPU-2 antiaircraft heavy machine guns. The air defense machine guns were positioned on high ground around the base. Defense of the approaches to the base was the responsibility of other Mujahideen groups.

In September 1985, the DRA moved elements of the DRA 12th Infantry Division from Gardez, with elements of the 37th and 38th Commando Brigades. They moved from Gardez circuitously through Jaji Maidan to Khost since the direct route through the Satakadow pass had been under Mujahideen control since 1981. This force joined elements of the 25th Infantry Division which was garrisoned in Khost. Shahnawaz Tani13 commanded this mixed force. The DRA military units had their full complement of weapons and equipment, but desertion, security details and other duties kept their units chronically understrength. Since the DRA could not mobilize sufficient force from one regiment or division, they practiced “tactical cannibalism” and formed composite forces for these missions.

Late one September afternoon, the DRA force began an infantry attack supported by heavy artillery fire and air strikes on Bari, which is northeast of Zhawar (Map 11-13 - Zhawar 1). Zhawar was not prepared for this attack since most of its major commanders, including Haqani, were on the pilgrimage to Mecca (the Haj). The DRA recaptured Bari and drove on to Zhawar. The Mujahideen reacted by positioning an 80-man group to block the ridge on the eastern slope of the Moghulgai mountains which form the eastern wall of the Zhawar base. The DRA force arrived at night and during the night fighting lost two APCs and four trucks. Eventually, the DRA became discouraged, withdrew and returned to Khost.14 Mujahideen from the nomad Kochi tribe, led by Malang Kochi, Dadmir Kochi and Gorbez Mujahideen, recaptured Bari.