Counterambush is a tedious, time-consuming effort requiring route planning, patrols, timely intelligence, counterambush drills and flank security. Planning should ensure that alternate routes and times of travel are used, that potential ambush sites are cleared and that movement through areas is coordinated with local forces. Movement details need to be safeguarded and deception measures taken to prevent ambush.

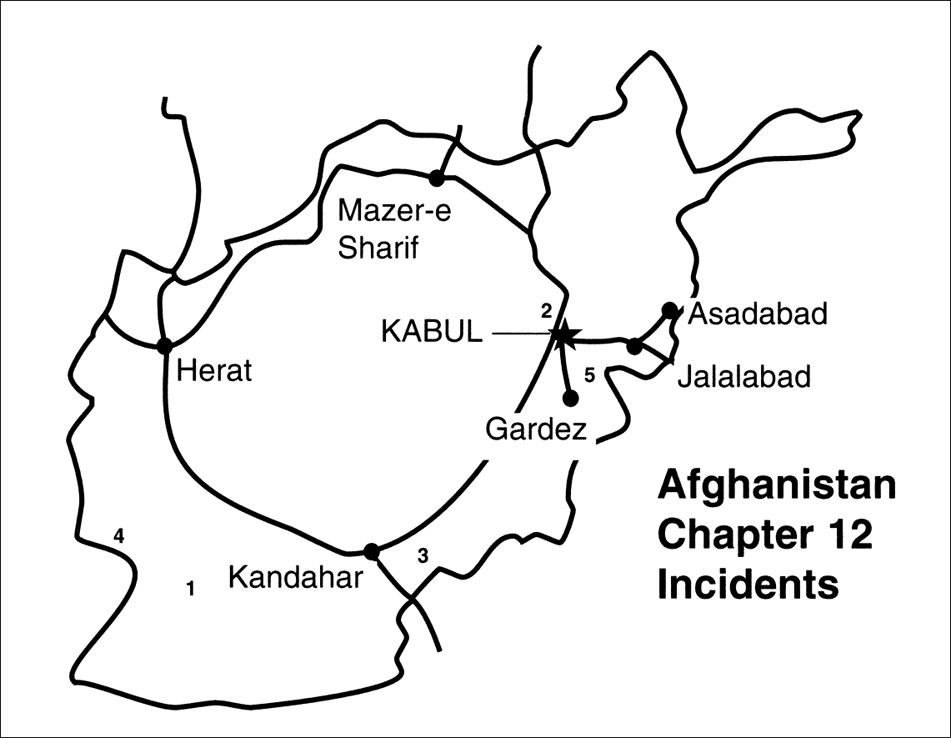

In 1983, we had one GMC pickup truck to support my force. We called GMC pickups ahu (deer), since they were fleet and nimble. It was the month of Ramadan and we were going from our base in Qala-e Naw to Kotalak to get some gasoline. Soviet soldiers were the main source of our gasoline. We would buy it from them. Our rendezvous point for gasoline was north of Kotolak. We left early in the afternoon and drove along the river avoiding the main roads (Map 12-1 - Kotolak). There was a Kochi1 in our truck who had visited our base and we were giving him a ride back to his village camp. As we got about 10 kilometers south of Kotolak, we saw the Kochi’s camp near the river. We stopped, both to let our passenger off and to wait for dark, since we were now within 50 kilometers of the Soviet base at Delaram and should not travel any further in the day light. We watched as the Kochi entered the woods some 500-600 meters away on his way to his camp. We saw some people attack him and drag him to the side. We didn’t know what was going on and thought that it was a fight between Kochis. “What’s going on?” we yelled. They did not answer so we fired some shots into the air. The people who grabbed the Kochi realized that they had been seen and started firing at us. We exchanged fire for about a half hour until helicopters landed behind the wooded area. The other group boarded the helicopters and left. It was late afternoon.

We had prematurely and inadvertently triggered a Soviet ambush. We were on the western bank of the Khash Rud river and the ambush force was on the eastern bank. Soviet ambushes were always better planned and prepared than those of the DRA. The Soviets would drop their ambush party by helicopter at night and the party would walk into position so that their ambush could not be detected. This ambush party was probably from Delaram2 and had probably moved into their wooded position the previous night. The Soviets suffocated the Kochi who had been our passenger and had killed another Kochi earlier in the same fashion. The river was fordable, so after the helicopters left, we forded the river to look at the ambush sight. Villagers found the bodies of the two murdered Kochi. We crossed back to the west side, got in our truck and began driving on the road to Kotolak since it was now night.

About two kilometers south of Kotolak the Soviets had set another ambush in some hills straddling the road. We were moving in enemy territory and I considered the route dangerous so we stopped short of the hills and I had seven of my men dismount and walk the road to the other side of the hills checking for ambushers. If they saw nothing, then we would move the truck forward. This left eight Mujahideen with the truck—three in the cab and five in the pickup bed. My seven walkers walked past the hills, checked for ambush and gave us an all-clear sign—a signal rocket.

The ambush party let my walkers pass through unmolested. When we saw the rocket, we moved out confidently. Suddenly, I thought that someone had set us on fire. We were in an ambush kill zone and bullets were flying all around us. Two men in the truck bed and the man next to me in the cab were killed. The driver was wounded in the shoulder. One tire was hit. The driver slammed the truck into reverse gear and tried to drive out of the kill zone. He drove the truck behind a sheltering hillock and stopped it. I had three KIA and two WIA. We changed the tire and left the area in the dark. My walkers continued to Kotolak. Later on, the walkers returned individually to my base camp. As we were reversing the truck out of the kill zone, the body of one of my dead Mujahideen fell out of the truck bed. The next day when we returned to recover his body, we discovered that it was booby trapped. We had to tie a rope to our dead comrade and drag him for a distance, before it was safe to carry him home for burial.

COMMENTARY: At the first ambush site, the Soviets failed to put out flank observers and consequently were surprised by the Mujahideen in their stationary truck. This failure compromised their ambush.

At the second ambush site, the Mujahideen walkers walked around the hills, not along the military crest where the ambushers should be. The ambushers wisely let the patrol pass to concentrate on the vehicle. However, the Soviets failed to employ directional, command-detonated mines or an RPG to effectively stop the truck in the kill zone. Further, the ambush commander did not know the size of the Mujahideen force and, following the ambush, did not pursue the Mujahideen or push out a patrol to determine the Mujahideen’s position and status.

After the first ambush, the Soviets knew that the Mujahideen intended to move north. It was also clear that the Soviets were in the area, yet the Mujahideen did not contact other local Mujahideen groups to check on Soviet and DRA activities in the area. The factionalized nature of the resistance prevented the spread of tactical intelligence which may have saved the Mujahideen from disaster.

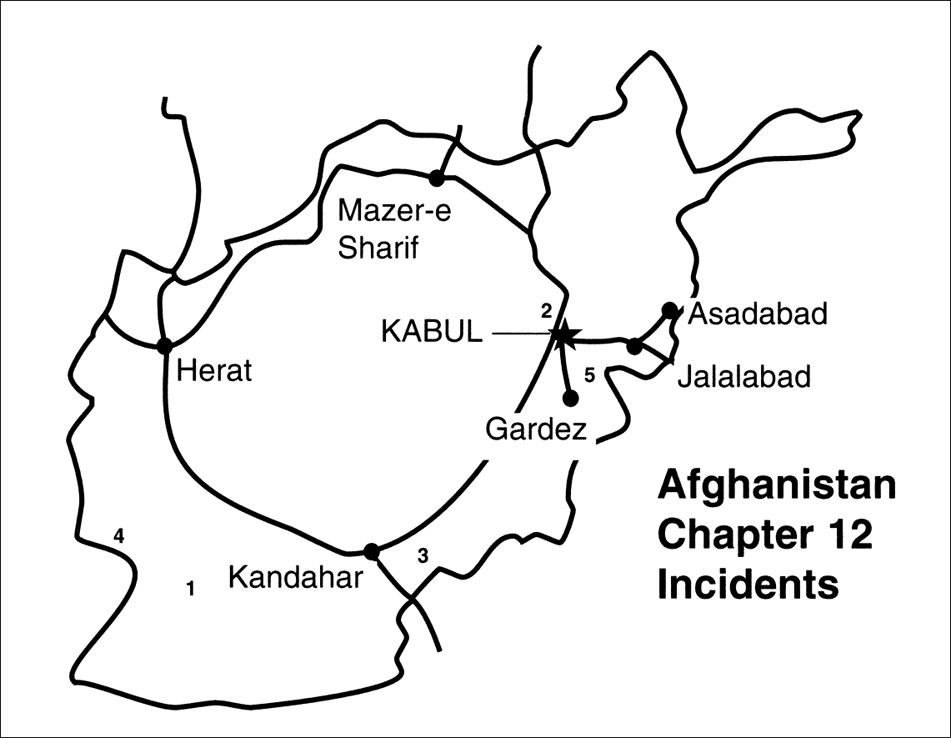

In April 1984, the regional Mujahideen called for a shura (local council) to discuss local issues and decide on common approaches. Sofi Rasul and myself were to attend as the local Mujahideen commanders from Farza. The meeting would be held five kilometers to our north in Estalif. We were accompanied by 28 Mujahideen armed with AK47s and two RPG-7s. Someone must have been working for DRA intelligence in our area, since the DRA knew about our plans and set an ambush on the trail near Farza.

We left Farza while it was still dark so that the enemy would not see us. Our route took us between two hills near a DRA air defense battery position (Map 12-2 - Farza). We were about half way to Estalif at a point which we call Wotaq, when the enemy opened fire on us from the surrounding hills. A DRA force had set up the ambush during the night. There is no doubt that they knew the exact route we would take. We went to ground in the kill zone and tried to find good fighting positions. The firing was fierce, we were totally surprised and we did not know the enemy strength and exact positions. Our return fire was ineffective and uncontrolled.

As dawn broke, our situation improved slightly, but we were still in shock. I had no command or control over my men and they acted as individuals trying to break contact and leave the kill zone. Enemy fire was still heavy. During a lull in the fighting, I managed to find a few Mujahideen sheltering in a ditch. I led them to the safety of the mountains in the west. Twelve Mujahideen eventually reached the safety of the terrain folds and mountain valleys in the west. Two others and myself were wounded. We remained hidden in the valley until we saw the ambush force leave that afternoon. Then we returned to the ambush site where we discovered that 18 of our comrades were killed. Some of their bodies were mutilated by the enemy and most had their clothing shredded. Late that afternoon, we moved their bodies for burial. I do not know if there were any enemy casualties, but during the fighting, I saw helicopters landing and taking off. They may have come to evacuate dead and wounded.

COMMENTARY: This successful DRA ambush inflicted more than 60 percent loss on the Mujahideen force. Soviet/DRA recruitment of local agents and informants gradually expanded their intelligence network in the Afghan rural areas. Often, agent/informant information was not timely, but when it was, the Soviet/DRA planners reacted to it. Intelligence was central to Soviet/DRA ambush planning and attempts to assassinate Mujahideen commanders. The Soviets/DRA usually conducted ambushes based on hard information and seldom placed random ambushes on the hope that a force might stumble into it.

If the Mujahideen felt that they were moving through uncontested territory, they often failed to post route security or send a forward and flanking patrols. This lack of attention to tactical security stemmed from the notion that they completely controlled the countryside and that the DRA/Soviet forces were unable to operate covertly in the countryside for long. This over-confidence cost the Mujahideen dearly. The Soviet/DRA forces exploited this Mujahideen hubris by setting ambushes even in areas located deep inside Mujahideen-controlled territory.

When ambushed, the Mujahideen had difficulty maintaining command and control. This exacerbated the situation and increased their casualties. Mujahideen commanders often failed to train their personnel in drills and counter-ambush procedures. In this example, the commander lost control immediately and failed to regain it. This was a contributing factor to the very-high Mujahideen losses. Further, the middle of a kill zone is no place to establish a defense. If the commander had a counterambush battle drill where his men immediately assaulted into the teeth of the ambush, more of his force might have survived.

It was in 1985. We had a large truck that we were hauling weapons, rockets and ammunition in from Pakistan to our base camp in the Argandab river valley (No map). We were taking a circuitous route. We neared Lora near sunset when we saw a helicopter. There was nowhere to hide since we were on an open plain. The helicopter landed and Soviet soldiers jumped out of it and took up positions all around us. We stopped the truck, jumped out and took up positions all around the truck. We had 13 Mujahideen and there were 10-12 Soviets. The Soviets had the advantage of better weapons, position and fire power. We started firing at each other. The Soviets started to advance on us. The driver was afraid that we would be captured, so he took a jerry can of gasoline, poured the gasoline onto the truck and set it on fire. He yelled at us to take cover. Despite the Soviet small-arms fire, we scurried to new positions for cover. Soon, the fire reached the ammunition and rockets and the truck exploded with a tremendous roar. The rockets and rounds were not stacked neatly, but were stacked in every possible direction. Consequently, the rockets and bullets were exploding and streaking off in every possible direction. It was spectacular. The explosion and flying rounds frightened the Soviets. They ran back to their helicopter and took off. After the helicopter left and things stopped exploding, we walked to a nearby village. Neither side had any casualties, but we lost a good truck and lots of ammunition and we had to walk back to our base camp.

COMMENTARY: The Mujahideen felt that they were in a secure area and were driving during the day. Usually, Mujahideen trucks moved at night. Evidently the Soviets hoped to capture the truck or they would have shot it up and created the same explosion that the Mujahideen did.

In 1986, we were moving three pickup trucks full of ammunition from Iran to our base. We had two motorcyclists patrolling five kilometers in front of the pickup trucks. We were near the border of Iran at Shand near Helmond lake. There is a point where two hills constrict the road and limit maneuver. The DRA border guard set up an ambush there (No map). Our two motorcyclists rode through the ambush zone and the DRA let them pass. As the motorcyclists cleared the ambush zone, they saw the DRA. They dismounted their motorcycles and took up firing positions on an adjacent hill. Our trucks rolled into the kill zone. The motorcyclists opened fire on the ambushers to warn the pickup trucks and to distract the ambushers. The DRA opened fire and hit the middle truck. The first pickup truck drove out of the kill zone while the Mujahideen in the last truck dismounted and attacked the ambushers. The DRA fled. We lost two Mujahideen KIA and one truck was damaged. There were no known DRA casualties.

COMMENTARY: When Mujahideen felt that they were in a secure area, they would move supplies during the day. The Mujahideen felt secure in this area since they were moving in the daylight. Still, they had a forward patrol checking for ambush. The patrol, however, seems road bound and did not get off the road to check likely ambush sites carefully. The patrol had no communication with the main body, so when the motorcyclists finally detected the ambush, they were unable to immediately contact them. Consequently, two of the three trucks were in the kill zone by the time the motorcyclists opened fire. Still, there was enough spacing between trucks which prevented the entire force from being in the kill zone simultaneously.

The Mujahideen showed aggressive spirit and resolve by immediately assaulting the ambushers and driving them from the scene. The DRA controlled the dominant terrain and had the opportunity to prepare fighting positions. They should have been able to stand, yet they fled in the face of Mujahideen resolve. The immediate assault into the ambush probably saved the Mujahideen convoy.

In May 1987, we were moving supplies from Peshawar, Pakistan to our base west of Kabul. We followed the Logar route from Parachinar, Pakistan across the Afghanistan border to Jaji in Paktiya Province. From there, we followed mountain canyons to Dobandi. Past Dobandi, the mountains ended and we had a broad plain to cross before we reached the mountains near our base. We finally reached Dobandi and stayed there for three days (Map 12-3 - Dobandi). We waited there while I made sure that the way was clear because the Soviets would set ambushes to interdict our supplies. I went from Dobandi to Kafar Dara canyon for information on Soviet activity. The Mujahideen at Kafar Dara did not have any information either, so I went on to Sepets where there were several Mujahideen bases belonging to HAR and Hezb-e Islami. These Mujahideen gave us two guides—Akhunzada of HAR and Mulla Nawab. We brought up all our supplies to Sepets in the late afternoon. Including the guides, I had 31 Mujahideen with me. I planned to go forward, clear the route, establish security positions on key terrain and likely ambush sites and then bring the supplies forward. I moved in the middle of the column.

We moved across the open plain from Sepets. There is a place called the Childrens’ cemetery where we stopped to offer our late afternoon prayers. Since it was still daylight, we moved well spread out with a distance between every Mujahideen. This was a precaution against air attacks. I told the guide, Mulla Nawab, to stay with us until we passed through this area and reached the Gardez highway. We followed a stream bed through a brush-covered area. We neared the water mill midpoint between Sepets and Khato Kalay at 1920 hours, when I looked at my watch to see if it was time for evening prayer. There was high ground on both sides of us. Suddenly machine-gun fire opened up in front of me. At first, I thought that it was my Mujahideen firing, but then I saw Soviets to the north firing on us. My Mujahideen immediately scattered and crouched behind bushes. The Soviets fired at the bushes, but my Mujahideen held their fire. The Soviets assumed that they had killed all my Mujahideen and jumped up from their positions. As I saw the Soviets jump up, I yelled “Allah Akbar”(God is the greatest) and we opened fire on them. This led to a prolonged fire fight. My Mujahideen were spread in a single file and I was the 16th person in the column. Dadgul was next to me, but we did not really know exactly where the Soviets were and they did not know exactly where we were. We fired at each other off and on. At approximately 2200 hours, we heard the sound of armored vehicle engines moving toward us. They had come from the northwest at Pul-e Alam. Mamur Abdul Ali began firing rockets in our support from his base in Sepets. One landed close to us and the next went further on. The fifth rocket landed in the enemy column. This slowed down the enemy column. Akhunzada also started firing rockets at the enemy column from his base. I instructed my Mujahideen to fall back to the mountains near Abchakan and then move south of Sepets to the mountain valley where the Mujahideen bases were located. It was 0200 when we reached Akhunzada base. Sixteen of my Mujahideen were missing—those who were in front of me in the column. The next morning at 1000 hours, we went forward and found Mohammaday, who was wounded and my RPG-7 man who was killed. The rest of my Mujahideen had gone on to Logar. I do not know what the Soviet losses were, but there were reports that they had casualties. The Soviets never used that particular ambush site again.

COMMENTARY: The Soviet ambush party probably came from the 108th Motorized Rifle Division or the 103rd Airborne Division. Both were garrisoned in Kabul. The 56th Air Assault Brigade at Gardez was closer to the site, but the relief element came from the Kabul direction. The Soviet ambush site was not well laid out. There was no attempt to seal the kill zone. There were no firing lanes cleared, no aiming stakes emplaced, no directional mines employed and no indirect fire planned on the kill zone. The Soviet ambush was triggered by a lone gunner and not by massed fire directed by the ambush commander. The Soviet commander evidently did not know that he had a strung-out Mujahideen column, which could not mass fires, to his front. Once night fell, the Mujahideen did not break contact and the ambush commander then evidently felt that he was in contact with a large force and called for an armored column to rescue him.

The Mujahideen movement plan was commendable. The commander did not hazard his supplies until he had cleared the route and posted security at key points. He coordinated with other factions to obtain information and tactical intelligence. He moved spread out on open terrain so he did not present an air target and moved in the middle of the column where he could best exert control. He gets low marks for following the guide down a stream bed without sending flankers to sweep the high ground. But, when his force was hit, the commander was able to ascertain that his column was not in immediate danger of annihilation and shut down return fire. This allowed his men to determine where their ambushers were and to draw them out of position. The commander ordered an escape to the northeast and then a move south in the safety of the mountains rather than retracing their route and risking another ambush or drawing the relief column into the Sepets area.

Successful counterambush is the result of careful planning, battle drills, rehearsals, information security, patrolling, current tactical intelligence, and deception measures. Movement of supplies needs to vary by route, time and composition of the supply column. Mujahideen supplies were moved on mule, horse, donkey, camel, truck and human porter. While some factions had their own transport, the bulk of Mujahideen supplies were carried by contracted teamsters and muleteers. The cost of transport was high and a group with a reputation of getting ambushed would be hard put to find willing teamsters.

In some areas, the Mujahideen only had to transport ammunition, but in other areas they had to transport food, clothing, and forage as well. Ammunition requirements for a small ambush by a 20-man group armed with Enfields, Kalashnikovs, an RPG-7, a PK medium machine gun, and five antitank mines, might exceed 375 pounds. The weight of required ammunition shoots up dramatically as mortars, recoilless rifles and heavy machineguns are added.3 Even if the ammunition was furnished free, the cost of getting it to where it was needed was considerable and the wise Mujahideen commander carefully protected his supplies against interdiction.

Mawlawi Mohayddin Baloch is from Nimroz province. His base was at Lowkhai, the Khash Rud district capítol on the Khash Rud river. He was initially with Malawi Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi of the Harakat-e lnqelab-i Islami (HAR). Later, on he switched to HIK (Khalis). [Map sheet 1680].

1 Kochi are nomadic tribesmen of Afghanistan. They live primarily by herding and trading sheep, goats and camels.

2 More probably, these were Spetsnaz from Lashkar Gah.

Commander Sofi Lal Gul is from Farza village of Mir Bacha Kot District. This is about 25 kilometers north of Kabul. He was affiliated with Mojaddedi’s Afghanistan National Liberation Front of Afghanistan (ANLF) during the war with the Soviets. Commander Sofi Lal Gul concentrated his efforts on the Kabul-Charikar highway. [Map sheet 2886, vie grid 0350].

Amir Mohammad was a combatant in Abdul Razik’s group in the Shahr-e Safa district northeast of Kandahar. There is no map with this vignette.

Mawlawi Mohayddin Baloch is from Nimroz province. His base was at Lowkhai, the capitol of Khash Rud district on the Khash Rud river. He was initially with Mawlawi Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi of the Harakat-e Inqelab-i Islami (HAR). Later, on he switched to HIK (Khalis). There is no map with this vignette.

Commander Haji Aaquelshah Sahak is from the Chardehi district of Kabul (a southern suburb). He was affiliated with NIFA. [Map sheet 2884, vie grid 3058].

3 “The Logistics System of the Mujahideen”, page 55, unpublished government contract study written in 1987.