IT IS FASHIONABLE to say that the individual is unique. Each is the product of his or her own heredity and environment and, therefore, is different from everyone else. From a practical standpoint, however, the doctrine of uniqueness is not useful without an exhaustive case study of every person to be educated or counseled or understood. Yet we cannot safely assume that other people’s minds work on the same principles as our own. All too often, others with whom we come in contact do not reason as we reason, or do not value the things we value, or are not interested in what interests us.

The merit of the theory presented here is that it enables us to expect specific personality differences in particular people and to cope with the people and the differences in a constructive way. Briefly, the theory is that much seemingly chance variation in human behavior is not due to chance; it is in fact the logical result of a few basic, observable differences in mental functioning.

These basic differences concern the way people prefer to use their minds, specifically, the way they perceive and the way they make judgments. Perceiving is here understood to include the processes of becoming aware of things, people, occurrences, and ideas. Judging includes the processes of coming to conclusions about what has been perceived. Together, perception and judgment, which make up a large portion of people’s total mental activity, govern much of their outer behavior, because perception—by definition—determines what people see in a situation, and their judgment determines what they decide to do about it. Thus, it is reasonable that basic differences in perception or judgment should result in corresponding differences in behavior.

As Jung points out in Psychological Types, humankind is equipped with two distinct and sharply contrasting ways of perceiving. One means of perception is the familiar process of sensing, by which we become aware of things directly through our five senses. The other is the process of intuition, which is indirect perception by way of the unconscious, incorporating ideas or associations that the unconscious tacks on to perceptions coming from outside. These unconscious contributions range from the merest masculine “hunch” or “woman’s intuition” to the crowning examples of creative art or scientific discovery.

The existence of distinct ways of perceiving would seem self-evident. People perceive through their senses, and they also perceive things that are not and never have been present to their senses. The theory adds the suggestion that the two kinds of perception compete for a person’s attention and that most people, from infancy up, enjoy one more than the other. When people prefer sensing, they are so interested in the actuality around them that they have little attention to spare for ideas coming faintly out of nowhere. Those people who prefer intuition are so engrossed in pursuing the possibilities it presents that they seldom look very intently at the actualities. For instance, readers who prefer sensing will tend to confine their attention to what is said here on the page. Readers who prefer intuition are likely to read between and beyond the lines to the possibilities that come to mind.

As soon as children exercise a preference between the two ways of perceiving, a basic difference in development begins. The children have enough command of their mental processes to be able to use the favorite processes more often and to neglect the processes they enjoy less. Whichever process they prefer, whether sensing or intuition, they will use more, paying closer attention to its stream of impressions and fashioning their idea of the world from what the process reveals. The other kind of perception will be background, a little out of focus.

With the advantage of constant practice, the preferred process grows more controlled and more trustworthy. The children become more adult in their use of the preferred process than in their less frequent use of the neglected one. Their enjoyment extends from the process itself to activities requiring the process, and they tend to develop the surface traits that result from looking at life in a particular way.

Thus, by a natural sequence of events, the child who prefers sensing and the child who prefers intuition develop along divergent lines. Each becomes relatively adult in an area where the other remains relatively childlike. Both channel their interests and energy into activities that give them a chance to use their mind the way they prefer. Both acquire a set of surface traits that grows out of the basic preferences beneath. This is the SN preference: S for sensing and N for intuition.

A basic difference in judgment arises from the existence of two distinct and sharply contrasting ways of coming to conclusions. One way is by the use of thinking, that is, by a logical process, aimed at an impersonal finding. The other is by feeling, that is, by appreciation—equally reasonable in its fashion—bestowing on things a personal, subjective value.

These two ways of judging would also seem self-evident. Most people would agree that they make some decisions with thinking and some with feeling, and that the two methods do not always reach the same result from a given set of facts. The theory suggests that a person is almost certain to enjoy and trust one way of judging more than the other. In judging the ideas presented here, a reader who considers first whether they are consistent and logical is using thinking judgment. A reader who is conscious first that the ideas are pleasing or displeasing, supporting or threatening ideas already prized, is using feeling judgment.

Whichever judging process a child prefers he or she will use more often, trust more implicitly, and be much more ready to obey. The other kind of judgment will be a sort of minority opinion, half-heard and often wholly disregarded.

Thus, the child who prefers thinking develops along divergent lines from the child who prefers feeling, even when both like the same perceptive process and start with the same perceptions. Both are happier and more effective in activities that call for the sort of judgments that they are better equipped to make. The child who prefers feeling becomes more adult in the handling of human relationships. The child who prefers thinking grows more adept in the organization of facts and ideas. Their basic preference for the personal or the impersonal approach to life results in distinguishing surface traits. This is the TF preference: T for thinking and F for feeling.

The TF preference (thinking or feeling) is entirely independent of the SN preference (sensing or intuition). Either kind of judgment can team up with either kind of perception. Thus, four combinations occur:

ST |

Sensing plus thinking |

SF |

Sensing plus feeling |

NF |

Intuition plus feeling |

NT |

Intuition plus thinking |

Each of these combinations produces a different kind of personality, characterized by the interests, values, needs, habits of mind, and surface traits that naturally result from the combination. Combinations with a common preference will share some qualities, but each combination has qualities all its own, arising from the interaction of the preferred way of looking at life and the preferred way of judging what is seen.

Whatever a person’s particular combination of preferences may be, others with the same combination are apt to be the easiest to understand and like. They will tend to have similar interests, since they share the same kind of perception, and to consider the same things important, since they share the same kind of judgment.

On the other hand, people who differ on both preferences will be hard to understand and hard to predict—except that on every debatable question they are likely to take opposite stands. If these very opposite people are merely acquaintances, the clash of views may not matter, but if they are co-workers, close associates, or members of the same family, the constant opposition can be a strain.

Many destructive conflicts arise simply because two people are using opposite kinds of perception and judgment. When the origin of such a conflict is recognized, it becomes less annoying and easier to handle.

An even more destructive conflict may exist between people and their jobs, when the job makes no use of the worker’s natural combination of perception and judgment but constantly demands the opposite combination.

The following paragraphs sketch the contrasting personalities that are expected in theory and found in practice to result from each of the four possible combinations of perception and judgment.

The ST (sensing plus thinking) people rely primarily on sensing for purposes of perception and on thinking for purposes of judgment. Thus, their main interest focuses upon facts, because facts can be collected and verified directly by the senses—by seeing, hearing, touching, counting, weighing, measuring. ST people approach their decisions regarding these facts by impersonal analysis, because of their trust in thinking, with its step-by-step logical process of reasoning from cause to effect, from premise to conclusion.

In consequence, their personalities tend to be practical and matter-of-fact, and their best chances of success and satisfaction lie in fields that demand impersonal analysis of concrete facts, such as economics, law, surgery, business, accounting, production, and the handling of machines and materials.

The SF (sensing plus feeling) people, too, rely primarily on sensing for purposes of perception, but they prefer feeling for purposes of judgment. They approach their decisions with personal warmth because their feeling weighs how much things matter to themselves and others.

They are more interested in facts about people than in facts about things and, therefore, they tend to be sociable and friendly. They are most likely to succeed and be satisfied in work where their personal warmth can be applied effectively to the immediate situation, as in pediatrics, nursing, teaching (especially elementary), social work, selling of tangibles, and service-with-a-smile jobs.

The NF (intuition plus feeling) people possess the same personal warmth as SF people because of their shared use of feeling for purposes of judgment, but because the NFs prefer intuition to sensing, they do not center their attention upon the concrete situation. Instead they focus on possibilities, such as new projects (things that haven’t ever happened but might be made to happen) or new truths (things that are not yet known but might be found out). The new project or the new truth is imagined by the unconscious processes and then intuitively perceived as an idea that feels like an inspiration.

The personal warmth and commitment with which the NF people seek and follow up a possibility are impressive. They are both enthusiastic and insightful. Often they have a marked gift of language and can communicate both the possibility they see and the value they attach to it. They are most likely to find success and satisfaction in work that calls for creativity to meet a human need. They may excel in teaching (particularly college and high school), preaching, advertising, selling of intangibles, counseling, clinical psychology, psychiatry, writing, and most fields of research.

The NT (intuition plus thinking) people also use intuition but team it with thinking. Although they focus on a possibility, they approach it with impersonal analysis. Often they choose a theoretical or executive possibility and subordinate the human element.

NTs tend to be logical and ingenious and are most successful in solving problems in a field of special interest, whether scientific research, electronic computing, mathematics, the more complex aspects of finance, or any sort of development or pioneering in technical areas.

Everyone has probably met all four kinds of people: ST people, who are practical and matter-of-fact; the sympathetic and friendly SF people; NF people, who are characterized by their enthusiasm and insight; and NT people, who are logical and ingenious.

The skeptic may ask how four apparently basic categories of people could have gone unnoticed in the past. The answer is that the categories have been noted repeatedly and by different investigators or theorists.

Vernon (1938) cited three systems of classification derived by different methods but which are strikingly parallel. Each reflects the combinations of perception and judgment: Thurstone (1931), by factor analysis of vocational interest scores, found four main factors corresponding to interest in business, in people, in language, and in science; Gundlach and Gerum (1931), from inspection of interest intercorrelations, deduced five main “types of ability,” namely, technical, social, creative, and intellectual, plus physical skill; Spranger (1928), from logical and intuitive considerations, derived six “types of men,” namely, economic, social, religious, and theoretical, plus aesthetic and political.

Another basic difference in people’s use of perception and judgment arises from their relative interest in their outer and inner worlds. Introversion, in the sense given to it by Jung in formulating the term and the idea, is one of two complementary orientations to life; its complement is extraversion. The introvert’s main interests are in the inner world of concepts and ideas, while the extravert is more involved with the outer world of people and things. Therefore, when circumstances permit, the introvert concentrates perception and judgment upon ideas, while the extravert likes to focus them on the outside environment.

This is not to say that anyone is limited either to the inner world or to the outer. Well-developed introverts can deal ably with the world around them when necessary, but they do their best work inside their heads, in reflection. Similarly well-developed extraverts can deal effectively with ideas, but they do their best work externally, in action. For both kinds, the natural preference remains, like right or left-handedness.

For example, some readers, who would like to get to the practical applications of this theory, are looking at it from the extravert standpoint. Other readers, who feel more interest in the insight that the theory may provide for understanding themselves and human nature in general, are seeing it from the introvert point of view.

Since the EI preference (extraversion or introversion) is completely independent of the SN and TF preferences, extraverts and introverts may have any of the four combinations of perception and judgment. For example, among the STs, the introverts (IST) organize the facts and principles related to a situation; this approach is useful in economics or law. The extraverts (EST) organize the situation itself, including any idle bystanders, and get things rolling, which is useful in business and industry. Things usually move faster for the extraverts; things move in a more considered direction for the introverts.

Among the NF people, the introverts (INF) work out their insights slowly and carefully, searching for eternal verities. The extraverts (ENF) have an urge to communicate and put their inspirations into practice. If the extraverts’ results are more extensive, the introverts’ may be more profound.

One more preference enters into the identification of type—the choice between the perceptive attitude and the judging attitude as a way of life, a method of dealing with the world around us. Although people must of course use both perception and judgment, both cannot be used at the same moment. So people shift back and forth between the perceptive and judging attitudes, sometimes quite abruptly, as when a parent with a high tolerance for children’s noise suddenly decides that enough is enough.

There is a time to perceive and a time to judge, and many times when either attitude might be appropriate. Most people find one attitude more comfortable than the other, feel more at home in it, and use it as often as possible in dealing with the outer world. For example, some readers are still following this explanation with an open mind; they are, at least for the moment, using perception. Other readers have decided by now that they agree or disagree; they are using judgment.

There is a fundamental opposition between the two attitudes. In order to come to a conclusion, people use the judging attitude and have to shut off perception for the time being. All the evidence is in, and anything more is irrelevant and immaterial. The time has come to arrive at a verdict. Conversely, in the perceptive attitude people shut off judgment. Not all the evidence is in; new developments will occur. It is much too soon to do anything irrevocable.

This preference makes the difference between the judging people, who order their lives, and the perceptive people, who just live them. Both attitudes have merit. Either can make a satisfying way of life, if a person can switch temporarily to the opposite attitude when it is really needed.

Under the theory presented here, personality is structured by four preferences concerning the use of perception and judgment. Each of these preferences is a fork in the road of human development and determines which of two contrasting forms of excellence a person will pursue. How much excellence people actually achieve depends in part on their energy and their aspirations, but according to type theory, the kind of excellence toward which they are headed is determined by the inborn preferences that direct them at each fork in the road.

Under this theory, people create their “type” through exercise of their individual preferences regarding perception and judgment. The interests, values, needs, and habits of mind that naturally result from any set of preferences tend to produce a recognizable set of traits and potentialities.

Individuals can, therefore, be described in part by stating their four preferences, such as ENTP. Such a person can be expected to be different from others in ways characteristic of his or her type. To describe people as ENTPs does not infringe on their right to self-determination: They have already exercised this right by preferring E and N and T and P. Identifying and remembering people’s types shows respect not only for their abstract right to develop along lines of their own choosing, but also for the concrete ways in which they are and prefer to be different from others.

It is easier to recognize a person’s preferred way of perception and way of judging than it is to tell which of the two is the dominant process. There is no doubt that a ship needs a captain with undisputed authority to set its course and bring it safely to the desired port. It would never make harbor if each person at the helm in turn aimed at a different destination and altered course accordingly.

In the same way, people need some governing force in their makeup. They need to develop their best process to the point where it dominates and unifies their lives. In the natural course of events, each person does just that.

For example, those ENTs who find intuition more interesting than thinking will naturally give intuition the right of way and subordinate thinking to it. Their intuition acquires an unquestioned personal validity that no other process can approach. They will enjoy, use, and trust it most. Their lives will be so shaped as to give maximum freedom for the pursuit of intuitive goals. Because intuition is a perceptive process, these ENTs will deal with the world in the perceptive attitude, which makes them ENTPs.

They will consult their judgment, their thinking, only when it does not conflict with their intuition. Even then, they will use it only to a degree, depending on how well developed it is. They may make fine use of thinking in pursuit of something they want because of their intuition, but ENTPs will not permit thinking to reject what they are pursuing.

On the other hand, those ENTs who find thinking more attractive than intuition will tend to let their thinking take charge of their lives, with intuition in second place. Thinking will dictate the goals, and intuition will only be allowed to suggest suitable means of reaching them. Since the process they prefer is a judging one, these ENTs will deal with the world in the judging attitude; therefore they are ENTJs.

Similarly, some ESFs find more satisfaction in feeling than in sensing; they let their feeling take charge of their lives, with sensing in second place. Feeling is then supreme and unquestioned. In any conflict with the other processes, feeling dominates. The lives of these ESFs will be shaped to serve their feeling values. Because of the preference for feeling, a judging process, they will deal with the world in the judging attitude. They are ESFJ.

ESFJs will pay real attention to their perception, their sensing, only when it is in accord with their feeling. Even then, they will respect it only to a degree, depending on how well they have developed it. They will not acknowledge doubts raised by the senses concerning something valued by their feeling.

However, other ESFs find sensing more rewarding than feeling and will tend to put sensing first and feeling in second place. Their lives will be shaped to serve their sensing—to provide a stream of experiences that provide something interesting to see, hear, taste, or handle. Feeling will be allowed to contribute but not to interfere. Because sensing, a perceptive process, is preferred, these ESFs will deal with the world in the perceptive attitude, and therefore they are ESFPs.

This phenomenon, of the dominant process overshadowing the other processes and shaping the personality accordingly, was empirically noted by Jung in the course of his work and became, along with the extraversion-introversion preference, the basis of his Psychological Types.

Some people dislike the idea of a dominant process and prefer to think of themselves as using all four processes equally. However, Jung holds that such impartiality, where it actually exists, keeps all of the processes relatively undeveloped and produces a “primitive mentality,” because opposite ways of doing the same thing interfere with each other if neither has priority. If one perceptive process is to reach a high degree of development, it needs undivided attention much of the time, which means that the other must be shut off frequently and will be less developed. If one judging process is to become highly developed, it must similarly have the right of way. One perceptive process and one judging process can develop side by side, provided one is used in the service of the other. But one process—sensing, intuition, thinking, or feeling—must have clear sovereignty, with opportunity to reach its full development, if a person is to be really effective.

One process alone, however, is not enough. For people to be balanced, they need adequate (but by no means equal) development of a second process, not as a rival to the dominant process but as a welcome auxiliary. If the dominant process is a judging one, the auxiliary process will be perceptive: Either sensing or intuition can supply sound material for judgments. If the dominant process is perceptive, the auxiliary process will be a judging one: Either thinking or feeling can give continuity of aim.

If a person has no useful development of an auxiliary process, the absence is likely to be obvious. An extreme perceptive with no judgment is all sail and no rudder. An extreme judging type with no perception is all form and no content.

In addition to supplementing the dominant process in its main field of activity, the auxiliary has another responsibility. It carries the main burden of supplying adequate balance (but not equality) between extraversion and introversion, between the outer and inner worlds. For all types, the dominant process becomes deeply absorbed in the world that interests them most, and such absorption is fitting and proper. The world of their choice is not only more interesting, it is more important to them. It is where they can do their best work and function at their best level, and it lays claim to the almost undivided attention of their best process. If the dominant process becomes deeply involved in less important matters, the main business of life will suffer. In general, therefore, the less important matters are left to the auxiliary process.

For extraverts, the dominant process is concerned with the outer world of people and things, and the auxiliary process has to look after their inner lives, without which the extraverts would be extreme in the extraversion and, in the opinions of their better-balanced associates, superficial.

Introverts have less choice about participating in both worlds. The outer life is thrust upon them whether they want one or not. Their dominant process is engrossed with the inner world of ideas, and the auxiliary process does what it can about their outer lives. In effect, the dominant process says to the auxiliary, “Go out there and tend to the things that can’t be avoided, and don’t ask me to work on them except when it’s absolutely necessary.”

Introverts are reluctant to use the dominant process on the outer world any more than necessary because of the predictable results. If the dominant process, which is the most adult and conscientious process, is used on outer things, it will involve the introverts in more extraversion than they can handle, and such involvement will cost them privacy and peace.

The success of introverts’ contacts with the outer world depends on the effectiveness of their auxiliary. If their auxiliary process is not adequately developed, their outer lives will be very awkward, accidental, and uncomfortable. Thus there is a more obvious penalty upon introverts who fail to develop a useful auxiliary than upon the extraverts with a like deficiency.

In the extraverts, the dominant process, being extraverted, is not only visible but conspicuous. Their most trusted, most skilled, most adult way of using their minds is devoted to the outside world. Therefore it is the side ordinarily presented, the side others see, even in casual contacts. The extraverts’ best process tends to be immediately apparent.

With introverts, the reverse is true. The dominant process is habitually and stubbornly introverted; when their attention must turn to the outer world, they tend to use the auxiliary process. Except for those who are very close to introverts, or very much interested in work that they love (which is probably the best way of getting close to them), people are not likely to be admitted to the introverts’ inner worlds. Most people see only the side introverts present to the outer world, which is mostly their auxiliary process, their second best.

The result is a paradox. Introverts whose dominant process is a judging process, either thinking or feeling, do not outwardly act like judging people. What shows on the outside is the perceptiveness of their auxiliary process, and they live their outer lives mainly in the perceptive attitude. The inner judgingness is not apparent until something comes up that is important to their inner worlds. At such moments they may take a startlingly positive stand.

Similarly, introverts whose dominant process is perceptive, either sensing or intuition, do not outwardly behave like perceptive people. They show the judgingness of the auxiliary process and live their outer lives mainly in the judging attitude.

A good way to visualize the difference is to think of the dominant process as the General and the auxiliary process as his Aide. In the case of the extravert, the General is always out in the open. Other people meet him immediately and do their business directly with him. They can get the official viewpoint on anything at any time. The Aide stands respectfully in the background or disappears inside the tent. The introvert’s General is inside the tent, working on matters of top priority. The Aide is outside fending off interruptions, or, if he is inside helping the General, he comes out to see what is wanted. It is the Aide whom others meet and with whom they do their business. Only when the business is very important (or the friendship is very close) do others get in to see the General himself.

If people do not realize that there is a General in the tent who far outranks the Aide they have met, they may easily assume that the Aide is in sole charge. This is a regrettable mistake. It leads not only to an underestimation of the introvert’s abilities but also to an incomplete understanding of his wishes, plans, and point of view. The only source for such inside information is the General.

A cardinal precaution in dealing with introverts, therefore, is not to assume, just from ordinary contact, that they have revealed what really matters to them. Whenever there is a decision to be made that involves introverts, they should be told about it as fully as possible. If the matter is important to them, the General will come out of the tent and reveal a number of new things, and the ultimate decision will have a better chance of being right.

There are three ways of deducing the dominant process from the four letters of a person’s type. The dominant process must, of course, be either the preferred perceptive process (as shown by the second letter) or the preferred judging process (as shown by the third).

The JP preference can be used to determine the dominant process, but must be used differently with extraverts and introverts. JP reflects only the process used in dealing with the outside world. As explained earlier, the extravert’s dominant process prefers the outer world. Hence the extravert’s dominant process shows on the JP preference. If an extravert’s type ends in J, the dominant process is a judging one, either T or F. If the type ends in P, the dominant process is a perceptive one, either S or N.

For introverts, the exact opposite is true. The introvert’s dominant process does not show on the JP preference, because introverts prefer not to use the dominant process in dealing with the outer world. The J or P in their type therefore reflects the auxiliary instead of the dominant process. If an introvert’s type ends in J, the dominant process is a perceptive one, S or N. If the type ends in P, the dominant process is a judging one, T or F.

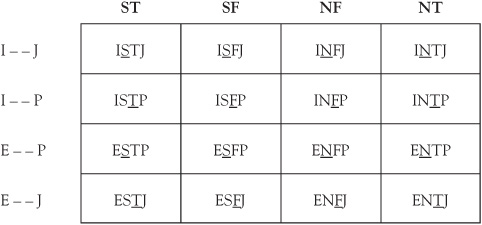

For ready reference, the underlined letters in Figure 1 indicate the dominant process for each of the sixteen types.

Extravert | Introvert |

The JP preference shows how a person prefers to deal with the outer world. | The JP preference shows how a person prefers to deal with the outer world. |

The dominant process shows up on the JP preference. | The auxiliary process shows up on the JP preference. |

The dominant process is used in the outer world. | The dominant process is used in the inner world. |

The auxiliary process is used in the inner world. | The auxiliary process is used in the outer world. |