Opposition and integration in the piano music

Brahms’s works for solo piano can be neatly grouped according to the four periods typically discerned within his music. The Sonata Op. 1, Sonata Op. 2, Scherzo Op. 4, Sonata Op. 5, Schumann Variations Op. 9 and Ballades Op. 10 are early pieces, dating from 1851 to 1854; the larger variation sets – Op. 21, Op. 24, Op. 35 – and Waltzes Op. 39 fall within the ‘first maturity’ (1855–76); the Klavierstücke Op. 76 and Rhapsodies Op. 79 belong to the ‘second maturity’ (1876–90); while the last four sets, Opp. 116–19, form part of the late music (1890–6). In addition to these solo works, the two piano concertos date respectively from 1854–9 and 1878–81, and there are of course numerous chamber compositions with piano. But the focus in this chapter is on Brahms’s solo piano music, in particular four works serving as cross-sections of the stylistic succession outlined above: the second movement from Op. 5, the Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Handel Op. 24, the Capriccio Op. 76 No. 5 and the Intermezzo Op. 118 No. 6.

My purpose in isolating these four is not only to complement the broad-brush approach taken by enough other authors to make such a survey redundant here, 1 but to explore the tension between what Denis Matthews calls ‘a definite plurality in Brahms’s musical makeup’ (three principal phases, respectively architectural, contrapuntal and lyrical in nature, defined by the use of classical forms in the early sonatas, the rediscovery of Bach and Handel in the variation sets, and the pre-eminence of melody in the late miniatures) 2 and, in contrast, the stylistic unity or integrity apparent from the composer’s very first works for piano through to his late music. As Matthews comments, Brahms’s style ‘was to change little in a lifetime. It was to undergo subtle refinements in technique, texture and harmony. But the vocabulary remained.’ 3 In a similar vein, Michael Musgrave notes that in Brahms’s œuvre , ‘there are no sudden changes of manner, no phases dominated by specific genres. The process is one of continuous integration and re-absorption of principles to new ends, and it is characterized by long consideration, endless revision and ruthless self-criticism. Experiments are there in plenty, but they have to be unearthed.’ 4

This dichotomy between stylistic integrity and stylistic evolution is apparent in our case-study pieces, as are different sorts of opposition that lie at the very heart of Brahms’s compositional dynamic. The inner compulsion of his music often derives from some manifestation of what might be termed the principle of opposition – whether an opposition between idioms (as in the second movement from Op. 5), between levels of intensity (as in the Handel Variations), between rhythm and metre (as in Op. 76 No. 5), or between motivic material and tonal structure (as in Op. 118 No. 6). Explicitly identified by some authors and alluded to by others, 5 this principle of opposition is part of what makes the music come alive in sound, or, more to the point, what enables it to make a cogent, coherent artistic statement from the complex forms and structures for which it and its creator are most commonly praised. Nevertheless, as we shall see by surveying the critical literature on each of the case-study pieces, the standard response is inclined to concentrate on ‘architectural’, or spatial, attributes rather than the music’s process – a tendency challenged in Edward T. Cone’s classic essay on ‘reading’ a Brahms intermezzo. 6 Although not without problems, Cone’s tripartite model usefully distinguishes between a ‘reading based on total or partial ignorance of the events narrated’, a ‘synoptic analysis [which] treats the story, not as a work of art that owes its effect to progress through time, but as an object abstracted or inferred from the work of art, a static artobject that can be contemplated timelessly’, and, in contrast, the ‘ideal reading’, one which views musical works in a ‘double trajectory’, both forward through time and retrospectively, with an appreciation of the ongoing temporal course and the contextualising whole. 7 Cone’s view that the second of these – ‘synoptic and atemporal’ in nature – does ‘scant justice to our experience of hearing a composition in real time’ 8 applies with uncanny relevance to much of the literature on Brahms, for whom (in Malcolm MacDonald’s words) ‘form was never a matter of abstract patterning, but the palpable articulation of the ebb and flow of feeling’. 9 It is ironic, therefore, that his exacting compositional method has so often inspired a formalistic critical reaction – one celebrating architecture rather than process. Without wishing to downplay the brilliance of his structural conceptions, I intend in this essay to identify some of what makes Brahms’s music work not just in the abstract but ‘in real time’, at once providing evidence of the principle of opposition that drives and shapes the four case-study pieces and, by concentrating on a wide array of compositional parameters (form, tonality, dynamics, rhythm, metre and motivic structure), exemplifying the purposeful tensions between a seemingly integrated musical style and one which itself experienced temporal progression.

The vocal and the symphonic in Op. 5

Sitting at the piano he began to disclose wonderful regions to us. We were drawn into even more enchanting spheres. Besides, he is a player of genius who can make of the piano an orchestra of lamenting and loudly jubilant voices. There were sonatas, veiled symphonies rather [mehr verschleierte Sinfonien ]; songs the poetry of which would be understood even without words, although a profound vocal melody runs through them all; single piano pieces, some of them turbulent in spirit while graceful in form; again sonatas for violin and piano, string quartets, every work so different from the others that it seemed to stream from its own individual source. 10

Robert Schumann’s famous phrase ‘veiled symphonies’, from his account of Brahms’s visit to Düsseldorf in autumn 1853, can be interpreted in at least two ways: as an indication of the variegated timbral palette, dense textures and instrumental characterisations of at least some of the young composer’s music, but also as a commentary on the essentially non-pianistic nature of certain aspects of his piano style. To suggest that Schumann used the phrase censoriously would be ludicrous, but one might infer from it that this was music really suited to an orchestral medium, music therefore in disguise (verschleiert ).

Some of the criticisms levelled at the early sonatas and other juvenilia stem from this conflict between a tremendous compositional facility initially and most naturally exploited in piano and vocal repertoire, and a straining after something greater – a musical utterance of truly symphonic dimensions. Brahms’s symphonic inclinations would of course be realised only later, first of all in the Piano Concerto Op. 15, but meanwhile they may actually have succeeded in frustrating the flow of the solo piano music. As early as 1862, Adolf Schubring remarked on ‘the padded counterpoint and the overloaded polyphony’ that contribute to the ‘failure’ of Op. 5 (a work which fits Schumann’s description of ‘veiled symphonies’ better than any other, according to Musgrave 11 ), as well as the ‘feebleness and stagnation’ resulting from the first movement’s doggedly monomotivic construction. 12 Echoing Schubring, Walter Frisch attributes the ‘stiff, even clumsy’ nature of the exposition to ‘Brahms’s emphasis on transformation at the expense of development’, concluding that the ‘movement is rescued from utter stagnation by the progression of the shapes [that is, stable melodic Gestalten ] toward what I have called lyrical fufillment or apotheosis’. 13

That same progression towards apotheosis occurs in the second movement, but effected by means of a remarkable change of idiom at the most unexpected moment in an initially straightforward ternary design. This Andante, along with the eventual fourth movement (‘Intermezzo: Rückblick’), predated the other movements in the Sonata and is one of few instrumental works by Brahms explicitly linked to a literary text – the first three lines from C. O. Sternau’s poem ‘Junge Liebe’. 14 Although Brahms himself observed that these verses are ‘perhaps necessary or pleasant for an appreciation of the Andante’, 15 it may be that the slow movement was closely modelled on the poem as a whole (as George Bozarth has argued), such devices as ‘melodic construction, texture, harmony, and variation procedure’ creating ‘tonal analogues which convey the mood, imagery, and meaning of the poem’. 16 Among the movement’s most remarkable features is its rhapsodic coda, which follows a conventional ABA′ succession in which the implied motion towards closure is thwarted at the last possible stage, opening into one of the most passionate outpourings in all of Brahms. Bozarth argues that ‘on first perusal, the coda would seem merely to function as a “textless” postlude, another grand apotheosis of a poet’s love, as in the Op. 1 Andante’, but its real ‘story’ can be understood by comparing it to a German folk-song ‘Steh’ ich in finst’rer Mitternacht’, about a young soldier recalling an ‘affectionate parting from his now distant beloved.’ 17

Without denying the elegance of Bozarth’s interpretation, I would counter that the movement’s force lies not so much in its extramusical associations as in the sudden, unforeseen abandonment of a vocal idiom (which may or may not correspond to the lovers in Sternau’s poem) for a symphonic one, the apotheosis at the end thus assuming the role of instrumental commentary on the love scene unfolded within the ABA′ stretch of the movement. There is good reason to suppose that such a function may have been intended by Brahms, given the similarity of two influential models. The first, Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (a cycle of six songs about another ‘distant beloved’), introduces an exciting piano postlude to round off the sixth song’s reprise of the opening music and to suggest a rapturous union of the two lovers, just as the piano postlude in the final number of Schumann’s Dichterliebe extends a repeated piano passage from the end of Song 12 to express the sense of reconciliation that the protagonist himself has been unable to articulate verbally. In both cases, the narrative conclusion or commentary is instrumental, not verbal, in nature, just as the piano-as-poet ‘speaks’ in the last work, ‘Der Dichter spricht’, in Schumann’s Kinderszenen (and, like the final postlude in Dichterliebe , employs a recitative style to do so).

If instrumental commentaries were therefore an established compositional device when Brahms came to write the Andante from Op. 5, the tremendous expressive crescendo at the end of this hitherto placid ‘Nachtstück’

18

had perhaps no such precedent. To appreciate its impact requires preliminary discussion of the movement as a whole. The main body, an ABA′ design moving through the keys of I, IV and I (respectively bars 1–36, 37–105 and 106–43, each section itself having a ternary construction),

19

uses a dialoguing of parts, usually soprano and tenor, presumably to represent the ‘zwei Herzen’ in Sternau’s poem.

20

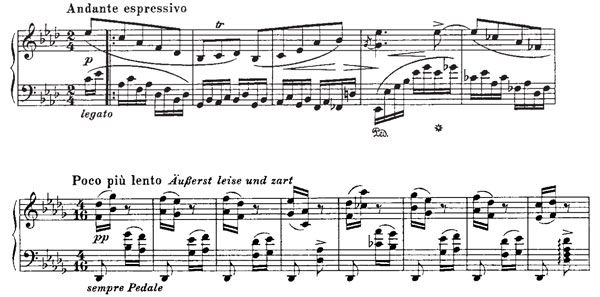

(See Example 4.1

.) Although the music occasionally grows more animated (for instance, at bar 92’s f

and con passione), Brahms retains a calm, restrained mood virtually throughout, as when section B enters, Poco più lento, pp

and ‘Äußerst leise und zart’. A′ promises to conclude as section A did (Example 4.2

compares the two endings), until an important deviation occurs at bar 139: over a rhythmically disruptive neighbour-note figure in the left hand (triplet semiquavers subdivided into groups of two), an extended cadential progression employing the minor subdominant unexpectedly moves to V

7

of D![]() major (hitherto acting as IV), whereupon the anticipated close of the movement is withheld and the ‘coda’ – in fact, a fourth principal section, C – tentatively begins, Andante molto, espressivo, ppp

and with una corda. Its key of D

major (hitherto acting as IV), whereupon the anticipated close of the movement is withheld and the ‘coda’ – in fact, a fourth principal section, C – tentatively begins, Andante molto, espressivo, ppp

and with una corda. Its key of D![]() major is the one in which the movement ends, in a most unorthodox manner, the conventional I–IV–I structure retrospectively interpretable as a large-scale V–I progression (in which the A

major is the one in which the movement ends, in a most unorthodox manner, the conventional I–IV–I structure retrospectively interpretable as a large-scale V–I progression (in which the A![]() major of sections A and A′ acts as dominant to the D

major of sections A and A′ acts as dominant to the D![]() major of sections B and, especially, C).

21

major of sections B and, especially, C).

21

Example 4.1 Brahms, Sonata Op. 5, movement 2, bars 1–5 and 37–44

Example 4.2 Brahms, Sonata Op. 5, movement 2, bars 32–7 and 137–48

However radical the sudden change of tonic might be, it is the new, expressively potent symphonic idiom prevailing from bar 144 onwards that most strikes the listener. The timpani-like pulsation on the pedalnote A![]() builds tension (despite Brahms’s ‘sempre pp

possibile’ marking in bar 157) until bar 164’s ‘molto pesante’ eruption at ff

, the thickened textures, driving triplet rhythm and questing harmonic motion explosively pushing towards climax at bar 174, the true coda (Adagio) then taking over at bar 179 and dissipating the overwhelming accumulated tensions with a final reminiscence of the ‘duet’ theme from section A.

builds tension (despite Brahms’s ‘sempre pp

possibile’ marking in bar 157) until bar 164’s ‘molto pesante’ eruption at ff

, the thickened textures, driving triplet rhythm and questing harmonic motion explosively pushing towards climax at bar 174, the true coda (Adagio) then taking over at bar 179 and dissipating the overwhelming accumulated tensions with a final reminiscence of the ‘duet’ theme from section A.

Elaine Sisman comments on Brahms’s ability ‘to create new ambiguities, and hence to impart new aesthetic meaning to the traditional gestures’ of the ‘closed forms’ – variation, rondo, ternary. The last of these in particular establishes ‘a set of firm expectations in the listener . . . Yet Brahms found his most intimate voice in this form, which he transformed with a profound change in the relationships among the expected three sections.’ 22 In Op. 5 this transformation is achieved not only by the unconventional modulation to the previous subdominant, but also by the shift from a vocal medium to a symphonic one – a fundamental change of idiom intended to articulate the ‘poetic’ commentary. As Malcolm MacDonald observes, here and in other early works Brahms ‘discovered how to make an orchestra speak through the medium of the keyboard’, 23 and its significance in this slow movement derives from an essential opposition to the main body of the work – an opposition so stark, and underpinned by such an unusual key progression, that it would threaten to pull the music apart were the composer’s powers of integration less assured than those of the young Brahms. Instead, the remarkable opposition paradoxically draws the movement into a unified statement far transcending in expressive effect the conventional ABA′ succession promised early on, and in this regard it serves as a harbinger of much of the piano music that Brahms would write in his ‘first maturity’ and well beyond.

Continuity in flux: the Handel Variations as gesture

The literature on Brahms’s Handel Variations is filled with ecstatic praise for this musical colossus: ‘one of the most important piano works he ever created’; 24 ‘completest mastery of the Variation form’; 25 ‘great enrichment of keyboard idiom’, ‘highly individual’ detail, ‘strength of form’; 26 ‘miraculously balanced’ freedom and ‘adherence to the rules’; 27 ‘massive scale and exhaustive command of piano technique’, ‘dwarfs all his previous variation sets’; 28 ‘ranks with the half-dozen greatest sets of variations ever written’, ‘represents a rediscovery of the fundamental principles of the form’. 29 Musgrave notes that between Op. 21 and Op. 24 Brahms assiduously sought out ‘more rigorous, complex and historical models’, among others preludes, fugues, canons and the then obscure dance movements of the Baroque period.Yet ‘his characteristic pianism – his chains of thirds and sixths and rigorous contrary motion which produce harsh and unstylistic dissonances’ – still prevailed, in a juxtaposition of keyboard styles ‘far removed from his earlier style with those more common in the time . . . achieving through his own natural feeling for them a mediation with his natural pianism’. 30

Perhaps more than in any other work thus far, Brahms’s mastery of structure is supremely evident, along with a vocabulary of pianistic textures and gestures the richness of which cannot be exhausted even in twenty-five variations or the monumental fugue at the end. It is not surprising, therefore, that considerable scholarly attention has been devoted to the work’s architectural properties, albeit sometimes at the expense of the musical process (as suggested earlier). Heinrich Schenker, for instance, individually analyses the theme, variations and fugue in his lengthy study, virtually neglecting the sum of these parts (although in a final section – ‘Noch etwas zum Vortrag’ – he does provide a dynamic representation of the theme and then discusses articulation, agogic shaping and so forth). 31 Others are content simply to identify the stylistic characters of the successive ‘movements’ (inspired, for instance, by Hungarian, music-box and harpsichord idioms), while a spatial representation of the whole is offered by Hans Meyer, 32 who advances the following roughly symmetrical model comprising four ‘unified blocks’ divided by the pivotal thirteenth variation and counterbalanced by the 109-bar fugue:

An altogether different approach is taken by Jonathan Dunsby, who observes that ‘at some level of the structure . . . Brahms usually creates a functional ambiguity, giving his music its typically elaborate and complex character’. In Dunsby’s study, ‘cases of simple, ambiguous formation are created by isolating the first two bars of each variation’, which ‘are analyzed as a complex of binary oppositions. A graphic model is formulated for each type of ambiguous structure, and the results are tabulated to see whether there is any pattern through the work.’ His ‘table of transformations’ depicts ‘categories of articulation, each one being a summary of the structure’, and reflects a binary/ternary ambiguity present at least at the start of each variation. Over and above this unifying feature, says Dunsby, ‘the reappearances of the Aria ’s structure articulate the piece as a whole’. 33

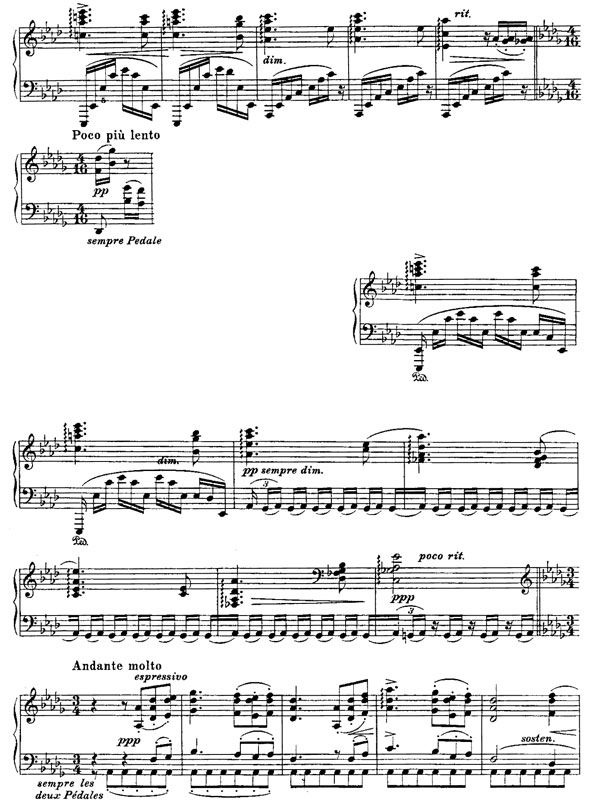

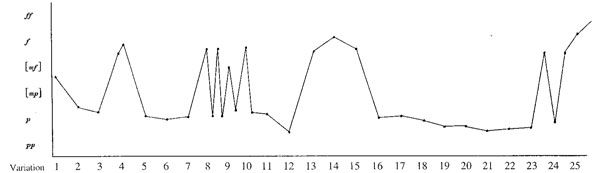

Although it succeeds in identifying at least one ‘continuing element’ in the variations, 34 Dunsby’s analysis hardly captures what MacDonald calls ‘the grand sweep of the structure’, 35 nor for that matter would the model sketched in Edward Cone’s essay ‘On Derivation: Syntax and Rhetoric’, 36 which focuses on small-scale progression and succession in theme-andvariation works rather than the broader gesture. In Op. 24 that sort of gesture – which is naturally of vital importance to the performer of the set, and what most listeners will apprehend first and foremost – could be defined in many different ways, but I shall confine myself to investigating Brahms’s expression markings, particularly his dynamic indications, for these clearly point to an underlying ‘shape’ in the work. Table 4.1 summarises the key relationships and principal expressive markings in the twenty-five variations, the latter determined in most cases by the indication at the start of each variation. Using this information, Example 4.3 charts an intentionally simplistic graph of the varying levels of dynamic intensity, 37 revealing peaks at Variations 4, 8–10, 13–15 and, most profoundly, 23–5, which sweep in an accelerando of momentum towards the climactic fugue. What is especially striking in both Table 4.1 and Example 4.3 , however, is the polarisation of soft and loud dynamic levels – pp and p versus f and ff , with practically nothing specified between these apart from occasional crescendo and decrescendo indications and the initial ‘poco f ’ . This terracing of opposed dynamics, especially obvious in the back-and-forth swings of Variations 8–10 and 23ff., is possibly as Baroque in origin as the very theme, which carves a rather more incrementally fluctuating, give-and-take progression through registral space (see Example 4.4 ), played on the piano with minutely changing dynamic levels.

Table 4.1 Expression and tonality in Brahms, Handel Variations Op. 24, Variations 1–25

Example 4.3 Brahms, Handel Varations Op. 24, Variations 1–25: dynamic flux

Example 4.4 Brahms, Handel Varations Op. 24, Aria: theme and and registral flux

The conclusion of all this is that Brahms takes pains to control the intensity level throughout the twenty-five variations, maintaining a state of flux in the first half, and then keeping the temperature perceptibly low after the peak of Variations 13–15 until the massive ‘crescendo’ towards the fugue begins in Variation 23. We thus find a sensitivity to motion and momentum that complements – and possibly transcends in importance to the listener – the elegance of structure about which so many authors have (legitimately) enthused. What makes the music’s course so powerful, however, is the opposition and indeed juxtaposition of dynamic maxima and minima, a throwback to the Baroque era but one that takes full advantage of the piano’s equal capacity for microscopic nuance and almost brute force.

It is in the fugue that the tension between dynamic extremes is played out once and for all. MacDonald writes that in this ‘astonishingly free’ fugal conception,

Brahms’s primary objective seems to have been to reconcile the linear demands of fugal form with the harmonic capabilities of the contemporary piano. Accordingly his hard-acquired polyphonic skills, manifest in innumerable subtleties of inversion, augmentation, and stretto, perfectly accommodate themselves to an overwhelmingly pianistic texture . . . The grand sweep of the structure, however, is never lost sight of: the immense cumulative power of this Fugue, gathered up in a chiming, pealing dominant pedal, issues in a coda of granitic splendour . . . 38

Musgrave reinforces this point: ‘more Bachian than Handelian in its exhaustive wealth of contrapuntal device’, the fugue uses

diminution, augmentation, and stretto, building to the final peroration through a long dominant pedal with two distinct ideas above. But the pianism is an equal part of the conception, and in this, the most complex example of Brahms’s virtuoso style, the characteristic spacings in thirds, sixths, and the wide spans beween the hands are employed as never before. Indeed, the pianistic factor serves to create the great contrasts within the fugue, which transcends a conventional fugal movement to create a further set of variations, in which many of the previous textures are recalled in the context of the equally transformed fugal theme. 39

If it is true, as Matthews claims, that ‘the Brahms player needs to think orchestrally in order to draw the strongest contrasts from a mere keyboard’, 40 then in the Handel Variations we find perhaps the pinnacle of Brahms’s ‘symphonic’ piano style, a style which may well have constrained him in certain earlier works (by provoking ‘padded counterpoint and overloaded polyphony’) but which would here be employed to maximum musical effect. Even so, his success in Op. 24 suggests not so much an evolution as an actualisation of style, one which eventually would shape the keyboard ‘miniatures’ composed some fifteen years later, after a long hiatus during which he produced no solo piano music at all.

Two against three in the Capriccio Op. 76 No. 5

Perhaps more than any of Brahms’s other solo piano works, the eight pieces in Op. 76 encapsulate the dichotomy identified earlier between a holistic compositional style and one experiencing continual change, occupying a central position (in Musgrave’s words) ‘between the character pieces of Brahms’s youth and the rich flowering of the later period, the four sets published in 1892 and 1893. Yet, though they offer strong contrast to the large-scale variation works which preceded them in the second period, they actually draw much from them.Variation becomes an integral part of their exploration of characters and moods.’ 41 As we shall see, this is particularly evident in the fifth work in the set, a quintessential example of the rhythmic and metrical opposition that was so vital a part of Brahms’s compositional discourse.

As David Epstein has noted, temporal phenomena in music, not least those related to ‘motion’, are particularly difficult to conceptualise, hence the lack of a vocabulary to capture ‘those seeming paradoxes and ambiguities of rhythm and metre’ that Brahms excelled in and that often cause a ‘disparity between how the music is heard and the way it is embodied in [the] score’. Nevertheless, says Epstein, in spite of its deepseated conflicts between metre and rhythm, Brahms’s music ‘in a fundamental sense is performance proof . . . its forward motion cannot be destroyed. Let the performer play the notes and the rhythms as they are written and the music must move . . . motion is built into the notes themselves, the inevitable product of their structure’, which ‘exerts its own control’. 42

Elsewhere I have questioned the validity of this hypothesis with regard to Brahms’s Fantasien

Op. 116,

43

but in the case of Op. 76 No. 5 one would be hard pressed to deny Epstein’s point. The work is riddled with temporal clashes, yet despite these – or perhaps because of them – it manages not only to cohere but to enact a drama of exceptional originality and fervour. MacDonald writes that ‘Brahms’s characteristic love of cross-rhythm, 3/4 alternating with 6/8 and duplets playing against triplets, is on especially lavish display in the . . . powerful [Op. 76] No. 5, a Capriccio in C![]() minor in an extended ternary form (with far-reaching variation of the basic material) which derives its dark passion from the motive energy such rhythmic ambiguities can supply.’

44

minor in an extended ternary form (with far-reaching variation of the basic material) which derives its dark passion from the motive energy such rhythmic ambiguities can supply.’

44

Musgrave’s extended description observes that

Variation comes into much clearer focus in the remarkable C![]() minor Capriccio No. 5. Here the alternating form A B A B1 A1 A2 (coda) indicates the successive application of variation to two basic sections, the first a prime example of Brahmsian cross-rhythm, 3/4 and 6/8 existing simultaneously . . . The two ideas are themselves rhythmically differentiated, the second building to very expansive pianism and modulating more widely. The repetition of A retains its original pattern for ten bars, after which it broadens to a lyrical cross-rhythmic passage ‘poco tranquillo’ . . . The variation [that ensues] is now rhythmic, a radical variation which recalls the third movement of the Second Symphony. Rhythmic variation of A then follows including change of mode to major ‘espress[ivo]’, the piece ending with a further rhythmic transformation – phrases of five quavers which completely obscure the metre – to a powerful climax.

45

minor Capriccio No. 5. Here the alternating form A B A B1 A1 A2 (coda) indicates the successive application of variation to two basic sections, the first a prime example of Brahmsian cross-rhythm, 3/4 and 6/8 existing simultaneously . . . The two ideas are themselves rhythmically differentiated, the second building to very expansive pianism and modulating more widely. The repetition of A retains its original pattern for ten bars, after which it broadens to a lyrical cross-rhythmic passage ‘poco tranquillo’ . . . The variation [that ensues] is now rhythmic, a radical variation which recalls the third movement of the Second Symphony. Rhythmic variation of A then follows including change of mode to major ‘espress[ivo]’, the piece ending with a further rhythmic transformation – phrases of five quavers which completely obscure the metre – to a powerful climax.

45

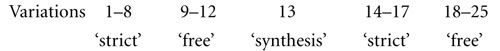

My own analysis differs in certain details from Musgrave’s, but what the diagram in Example 4.5

reveals perhaps more clearly than any prose description could is the fundamental tension between the chronological, narrative flow of the music and the structure as a whole that embraces it – a tension explicitly acknowledged in Cone’s analytical model (see above) and here thoroughly exploited by Brahms. Capitalising on the piano’s ability to layer textures ‘contrapuntally’,

46

he launches into the piece with three different metrical schemes in operation at once: a melody suggesting 3/4, a bass in 6/8 and a sinuous tenor line which could be read either way. (Example 4.6a

offers an analytical reinterpretation of the passage.) This multiplicity of organisational schemes is a foretaste of the fierce battle fought throughout the work, in which the notated 6/8 metre eventually gives way to 2/4 in bars 78–111, following the violent jockeying

back and forth between the two in bars 69–77 (effected by the sequential statements of ‘x’ – see Example 4.5

– in bars 69–70, 73–4 and 77). The modulation from one metre to another in this way is extraordinary in and of itself, but the fact that the work’s climax (in subsection a3

) occurs in the new metre and moreover in the parallel tonic, C![]() major (withheld until this point, and induced by the metrical displacement of the melody’s E

major (withheld until this point, and induced by the metrical displacement of the melody’s E![]() ), makes it especially remarkable. Even more striking is the ‘further rhythmic transformation’ mentioned by Musgrave and broken down in Example 4.6b

. The emergence of a new five-quaver group paying no real attention to the 6/8 notated in the score, with 5/8 implied in the lower parts and 3/4 - 1/8 in the upper (the start of each new phrase is almost like a syncopation, the full force of which can be projected in performance by means of a hiccup effect, that is, the tempo kept very steady indeed so that no ‘bending’ occurs), succeeds in initially suppressing expectations of metrical regularity, the sense of 5/8 disappearing with the extension to 5/8 + 1/8 in the lower systems and an at last untruncated 3/4 in the top line. This extension gives rise to the triplet implications of the left-hand octaves descending against the hemiola-like right-hand material, which in fact perpetuates the now well established 3/4 until the final sweep on the last beat of bar 115 – yet another momentum-generating extension. Here the right hand suddenly moves in triplets, while the left hand is both triple and duple in character, building terrific energy until the ‘true’ 6/8 metre is fully restored on the downbeat of bar 116, bringing the piece to a breathless close in just two bars.

47

), makes it especially remarkable. Even more striking is the ‘further rhythmic transformation’ mentioned by Musgrave and broken down in Example 4.6b

. The emergence of a new five-quaver group paying no real attention to the 6/8 notated in the score, with 5/8 implied in the lower parts and 3/4 - 1/8 in the upper (the start of each new phrase is almost like a syncopation, the full force of which can be projected in performance by means of a hiccup effect, that is, the tempo kept very steady indeed so that no ‘bending’ occurs), succeeds in initially suppressing expectations of metrical regularity, the sense of 5/8 disappearing with the extension to 5/8 + 1/8 in the lower systems and an at last untruncated 3/4 in the top line. This extension gives rise to the triplet implications of the left-hand octaves descending against the hemiola-like right-hand material, which in fact perpetuates the now well established 3/4 until the final sweep on the last beat of bar 115 – yet another momentum-generating extension. Here the right hand suddenly moves in triplets, while the left hand is both triple and duple in character, building terrific energy until the ‘true’ 6/8 metre is fully restored on the downbeat of bar 116, bringing the piece to a breathless close in just two bars.

47

Example 4.5 Brahms, Capriccio Op. 76 No. 5: metrical, formal and tonal structures

Brahms’s control over this temporal battle is consummate: while allowing it to rage not only within individual bars (as in Example 4.6a

and 4.6b

; compare also bars 53ff.) but in the metrical plan as a whole (especially the 6/8 versus 2/4 opposition at the highest level of temporal organisation), he maintains order largely by means of the straightforward harmonic foundation shown at the bottom of Example 4.5

. The three occurrences of section A, in the tonic C![]() minor (eventually, major), are punctuated by passages prolonging the dominant: first of all B1

, then C (in the minor dominant) and B2

. The smaller-scale i–V–i structures that emerge are seemingly contained within the ultimate progression through the climactic structural dominant in bars 103ff. to the tonic’s return in the coda, which itself ends with an emphatic V

7

–i cadence (Example 4.6b

).

minor (eventually, major), are punctuated by passages prolonging the dominant: first of all B1

, then C (in the minor dominant) and B2

. The smaller-scale i–V–i structures that emerge are seemingly contained within the ultimate progression through the climactic structural dominant in bars 103ff. to the tonic’s return in the coda, which itself ends with an emphatic V

7

–i cadence (Example 4.6b

).

Example 4.6 Brahms, Capriccio Op. 76 No. 5

(a) Metrical implications in bars 1–4

(b) Metrical implications in bars 111–17

Thus the relative simplicity of the tonal foundation counteracts the almost overwhelming metrical clashes in which Brahms revels, the piece embodying an opposition not just between duple and triple metres and subdivisions thereof (yet another manifestation of his seemingly insatiable appetite for two-against-three patternings) but between the de-stabilising temporal flow and the stabilising harmonic underpinnings, respectively centrifugal and centripetal in nature. For the listener or analyst to appreciate that opposition virtually requires an awareness of the ‘double trajectory’ described by Cone, that is, sensitivity to both the diachronic flow and the synchronic whole. 48

None of this is meant to suggest that the tonal plan is static, rather that it is solidly built and able to withstand the assault of the temporal conflict above. A notably different situation arises, however, in the last of our case-study pieces,Op.118 No.6,where the music’s tonal foundations are threatened to the very core, this challenge caused in part by a motivic shape whose pre-eminence virtually overwhelms all other structural aspects.

Music of the future: the ‘progressive’Brahms

According to MacDonald, Brahms’s last four sets of solo piano music, Opp. 116–19, ‘stand at the furthest possible remove from the rhetoric of the early sonatas or the pugnacious challenge of the large-scale variation sets. Though a few of them afford brief glimpses of the old fire and energy, the predominant character is reflective, musing, deeply introspective, and at the same time unfailingly exploratory of harmonic and textural effect, of rhythmic ambiguity, of structural elision and wayward fantasy.’ 49 Nevertheless, just as Brahms’s codas often serve a ‘summarising’ function in individual works, as it were drawing together seemingly disparate ideas from earlier on which in retrospect prove to be closely linked, certain compositions within the four opuses do more than simply glance back at previous stages within the solo piano output. Op. 118 No. 6 is one such piece, rich in symphonic implications, masterful in its control of counterpoint, poised on the brink of instability through extreme expressive contrasts and a tonal scheme as unorthodox in its way as that of Op. 5’s second movement. What is perhaps more noteworthy, however, is the Brahmsian legacy represented by this work, eventually taken up by such composers as Arnold Schoenberg, whose serial technique was at least partly inspired by the motivic working and in particular the ‘developing variation’ at which Brahms excelled and which is an important agent within Op. 118 No. 6. 50 Past and future are therefore united in this piece, its apparently idiosyncratic audacities part and parcel of the piano style practised for some fifty years, while paving the way for the revolution in musical language to come. Certainly its expressive profundity has been enthusiastically recognised by authors: ‘perhaps the most signficant and poetic of all the later pieces’; ‘deeply introspective . . . rises to an intensity not previously found’; ‘high drama and pathos’; ‘a movement portraying the utmost grief and passion’, in which Brahms’s ‘lesson’ is ‘the production of intensity of expression from the association of extremes ’. 51 Different authors have emphasised the work’s ‘orchestral’ qualities, some likening the opening to a duet for oboe and harp, others clarinet and harp. 52 MacDonald’s description is one such example:

The very opening, based on a wavering turn-figure, conjures up lonely clarinet and horn solos over harp arpeggios as profoundly plangent as those in the early ‘An eine Äolsharfe’ . . . Doubling in thirds (with the unmistakable

effect of flutes) only intensifies its bittersweet eloquence. A staccato, bitingly rhythmic music begins muttering in G![]() – an idea in Brahms’s most irascible vein: it starts sotto voce

and grows in decisiveness and vigour, with massive yet clipped chordal textures. But at the very moment of climax the ‘dies irae’ theme [from bars 1–4] is recalled, inextricably bound up with it, and this inspired work subsides into its former tragic monologue, dying out eventually in exquisite but bleak despair.

53

– an idea in Brahms’s most irascible vein: it starts sotto voce

and grows in decisiveness and vigour, with massive yet clipped chordal textures. But at the very moment of climax the ‘dies irae’ theme [from bars 1–4] is recalled, inextricably bound up with it, and this inspired work subsides into its former tragic monologue, dying out eventually in exquisite but bleak despair.

53

Other authors have focused their attention on how the work’s narrative course and underlying structure interrelate, one monitoring successive ‘listening passes’ to trace an evolving comprehension of the music, another attempting to devise ‘continuity schemes’ from the musical landscape as revealed through analysis.

54

In both cases, the work’s profound ‘mystery’ is freely acknowledged – not surprisingly, for this is among Brahms’s most inscrutable compositions. Like other late works (for instance, Op. 118 No. 1), it shuns a conventional tonal frame, only suggesting the tonic E![]() minor in the opening bars before a diminished seventh arpeggio in bars 3–4 et seq.

diverts the harmonic setting to an implied B

minor in the opening bars before a diminished seventh arpeggio in bars 3–4 et seq.

diverts the harmonic setting to an implied B![]() minor, and it is not really until the cadential

minor, and it is not really until the cadential ![]() in bar 71, after an extended developmental section reaching the work’s climax, that the fate of E

in bar 71, after an extended developmental section reaching the work’s climax, that the fate of E![]() minor as tonic is sealed once and for all.

minor as tonic is sealed once and for all.

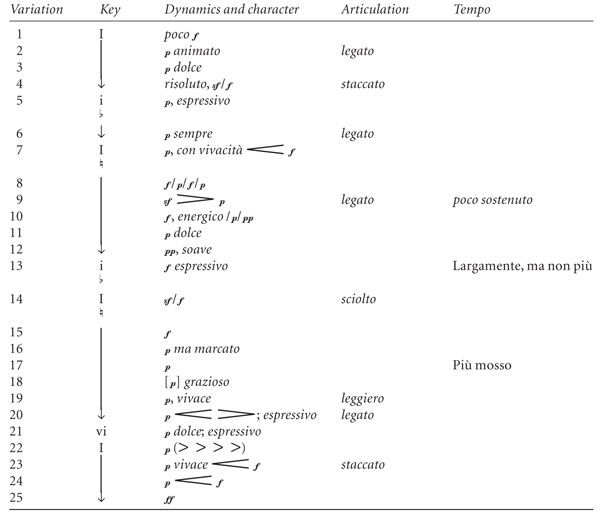

Example 4.7

provides excerpts from the piece, showing first of all the opening articulation of the motive-cum-theme. As I have already suggested, this convoluted shape – obsessively intoning three pitches over and over again – controls the flow of compositional events to an extraordinary extent, exemplifying and as it were justifying Schoenberg’s later celebration of Brahms’s ‘serial’ technique. The four-bar pattern returns an octave lower in bars 5–8 with a similar but not identical accompaniment, and it is then developmentally worked in bars 83

–16, with overlapping fragments of varying lengths in canonic dialogue. Bars 17–20 (shown in the example) transpose the motivic melody to a definitive B![]() minor, the ensuing E

minor, the ensuing E![]() minor return of the opening at bar 21 sounding more like a subdominant than a tonic. After a varied repeat of bars 1–20, the music’s character dramatically changes with new material that manages to escape the influence of the motivic theme for the first time in the piece. Here begins a more or less steady increase in activity and momentum, although the music initially stays close to the would-be tonic, B

minor return of the opening at bar 21 sounding more like a subdominant than a tonic. After a varied repeat of bars 1–20, the music’s character dramatically changes with new material that manages to escape the influence of the motivic theme for the first time in the piece. Here begins a more or less steady increase in activity and momentum, although the music initially stays close to the would-be tonic, B![]() minor, the emphatic cadential progression at bars 53ff. being deflected at the last minute to E

minor, the emphatic cadential progression at bars 53ff. being deflected at the last minute to E![]() minor (see Example 4.7

and MacDonald’s comments above). Ironically, it is the unexpected reappearance of the hitherto tonally destabilising main motive that achieves this deflection. The temperature rises even higher, transposed and enriched material from bars 49–52 energetically pushing towards a cadence

promising finally to establish E

minor (see Example 4.7

and MacDonald’s comments above). Ironically, it is the unexpected reappearance of the hitherto tonally destabilising main motive that achieves this deflection. The temperature rises even higher, transposed and enriched material from bars 49–52 energetically pushing towards a cadence

promising finally to establish E![]() minor as tonic – but, at the height of the music’s drama, this arrival is itself deflected, once again by the restatement in 59ff. of the motivic melody now reharmonised in an implied D

minor as tonic – but, at the height of the music’s drama, this arrival is itself deflected, once again by the restatement in 59ff. of the motivic melody now reharmonised in an implied D![]() major (see Example 4.7

), in one of the most impassioned and poignant passages in the composer’s entire output. At this climactic moment we realise just how completely the shape eclipses all other structural considerations, its search for a stable identity still frustrated. Nevertheless, the music starts winding down with further developmental iterations of the motive, the successive Neapolitan settings (respectively suggesting B

major (see Example 4.7

), in one of the most impassioned and poignant passages in the composer’s entire output. At this climactic moment we realise just how completely the shape eclipses all other structural considerations, its search for a stable identity still frustrated. Nevertheless, the music starts winding down with further developmental iterations of the motive, the successive Neapolitan settings (respectively suggesting B![]() minor and E

minor and E![]() minor) in bars 663

–70, beautifully evocative with their doublings in sixths and thirds, finally leading to the cadential

minor) in bars 663

–70, beautifully evocative with their doublings in sixths and thirds, finally leading to the cadential ![]() referred to above. Before this the music escapes from the insistent motivic shape for a few more bars (bars 41–52 and 552

–91

are the only other passages in the piece making no explicit reference to it), until at last it enters in the context of E

referred to above. Before this the music escapes from the insistent motivic shape for a few more bars (bars 41–52 and 552

–91

are the only other passages in the piece making no explicit reference to it), until at last it enters in the context of E![]() minor, the passage shown in Example 4.7

concluding the work in a resigned state.

55

minor, the passage shown in Example 4.7

concluding the work in a resigned state.

55

Example 4.7 Brahms, Intermezzo Op. 118 No. 6

(a) bars 1–51

(b) bars 17–211

(c) bars 53–5

(d) bars 59–62

(e) bars 81–6

To characterise Op. 118 No. 6 as a motive in search of a tonic would hardly do justice to the tremendous dramatic impulse generated by Brahms’s incessant reharmonisations of the almost ubiquitous melodic shape. That this should be the case is both a testimony to Brahms’s compositional genius 56 and an ironic rebuttal of some of the criticisms levelled at his early music, mentioned before in this chapter. Having initially noted the comparative stasis of certain ‘monomotivic’ compositions from the 1850s, putatively overburdened by their symphonic aspirations, we now encounter a particularly ‘progressive’ piece whose inner energies are activated and fully realised by an obsession with a single motive, the ‘groundlessness’ of which inspires a most unusual tonal plan. Moreover, Brahms’s contrapuntal handling, especially deft when the doubled sixths and thirds enter over two successive Neapolitans, is magnificent, as is his ability to unite material at opposite ends of the expressive spectrum, alternately projecting bleak despair and (hollow?) triumph. Even more intriguing, however, is the way in which Brahms provides only the vaguest hints about what the work might ‘mean’, about the solution to the ineffable mystery that it poses. Although frustrating, the fact that its message will remain forever veiled and subject to speculation is of course part of the appeal of this and much of Brahms’s other piano music, which thrives upon paradox and opposition almost to the point that its essential integrity is called into question.