Words for music: the songs for solo voice and piano

Brahms’s view of song

Brahms wrote songs throughout his life. 1 They provide a constant backcloth to his larger instrumental works, to which they often relate quite tangibly. A solid core has remained in the repertory since Brahms’s time, and they are well represented in the current recording catalogue, as prominent as those of his predecessors Schubert and Schumann, whom he so admired. Yet there has always been a discernible tendency among critics to exclude Brahms from an ultimate canon of great German Lieder composers comprising Schubert, Schumann and Wolf; indeed Brahms is even sometimes included in a list with much lesser figures of the genre such as Mendelssohn, Franz and Cornelius. There are obvious reasons for this. First of all, the fact that Brahms did not set the greatest poems, rather preferring the work of minor figures, whose verse he might more easily transform: from this it is assumed that he lacked the knowledge of or the discernment of the composers who did. Since by this reckoning, great songs are seen as critiques of great poetry, responding to the challenge presented by a poem which is independently known, Brahms’s songs are excluded since they offer no such comparisons. To this conclusion is harnessed the fact that Brahms is sometimes seen as displaying awkwardness in the musical rendering of verbal accentuation, a consequence of his emphasis on rounded melody. One might further add in such an assessment that Brahms avoids the lengthy groups or cycles that show a capacity for reflecting psychological development. In short, that he is an instrumentally rather than verbally driven composer.

These are negative comparisons, ones which ignore that Brahms’s songs were based on a wide and discerning knowledge of German literature; that as a corpus they display a remarkable range of expression in both vocal and instrumental domains; and that they have great qualities of their own which are based on a clearly held aesthetic. Certainly Brahms did avoid setting the famous lyrics and cycles which are so central to the literature of nineteenth-century German song: for example, the lyrics from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister or his Faust , or the cycles by romantic poets such as Heine and Eichendorff. There are hardly any comparable settings by Brahms. Although he later admitted to having set ‘the whole of Eichendorff and Heine’ when young, 2 few survive, namely of Eichendorff in Op. 3 Nos. 5 and 6, Op. 7 Nos. 2 and 3 and the single ‘Mondnacht’ (WoO 21); 3 his own surviving Heine settings were apparently written much later. But this is in itself no evidence of insensitivity to poetry. On the contrary, Brahms’s choices were based on a passion for literature apparent from childhood. He believed that a great poem gained nothing from musical setting: consider his familiar comment on Goethe settings by Schubert, whose songs he greatly admired: ‘in my opinion, Schubert’s “Suleika” songs are the only of his settings where the music enhanced the words. In all other cases the poems are so perfect that they need nothing added.’ 4 Instead, he explored more widely, using foreign poems in translation and including verse with special personal association – with friends and with his home region. It was only in large-scale choral music that he allowed himself more freedom: all four major works with orchestra to secular texts use important poetry. 5 On the other hand, he did not align himself with those who sought to interpret poetry by shifting the balance decisively towards music. As he commented to Henschel: ‘there are composers who sit at the piano [and compose the poem] from A to Z until it is done; they see something finished, something important in every bar’. 6 His aims differed both from those of Schubert and Schumann and from those of the ‘composers who sit at the piano’, but they were clearly defined; and his settings always show the composer responding to distinctive technical challenges within his defined terms of reference. Brahms’s aesthetic emerges clearly through his contact with Henschel, and through his teaching of Gustav Jenner, his only pupil, in the 1870s and 1880s. It was based on the principle of strophic composition. Jenner comments:‘I always thought he valued strophic songs more than any others [though] he never expressly said so.’ 7 He insisted on the close relation of the rhythm and form of the poem to that of the music: it was well known that Brahms’s aesthetic canon demanded that the metre of a song should reflect, in one way, or another, the number of metrical feet in the poem. 8 Elsewhere Brahms asserted that he set the words and not the emotions or imagery of the words, as when he commented of the Magelonelieder , ‘my music has . . . nothing whatever to do with [Ludwig Tieck’s Phantasus and the love story of Peter]. I have really only set the words and nobody need be concerned about the landscape’, 9 by which he seems to mean that he set the qualitative and quantitative properties of the words and their larger patterning within the structure of the poem, rather than as topics for individual depiction or ‘expression’ through traditional ‘word painting’. His remark is, of course, a trifle disingenous. His melodies and their accompaniments do create atmosphere, and mark a new stage of expressive development; but rounded, self-sufficient melody and clear harmonic support allied to natural verbal rhythms remained central to his style.

The ideal he had in mind emerges clearly in a comment made to Clara Schumann in 1860: ‘song composition is today sailing on so false a course that one cannot too often remind oneself of the ideal, which for me is folk-song’. 10 As much could have been deduced from his previous output, in which he had already made extensive use of folk-song texts in original settings as well as arrangements, including fourteen settings for Clara’s children; and his interest was to last to the end of his life when he released his arrangements of 49 Deutsche Volkslieder for solo voice and piano, claiming that no work had given him as much pleasure. Other unpublished solo arrangements also survive, as well as settings for many choral groupings.

His favourite folk-songs were all extremely simple in structure, with balancing phrases and a syllabic style, implying a simple harmonic support, and with no repetition of text. They represented a romantic ideal, songs whose very simplicity and stylisation embodied a quality of perfection. That Brahms made his comment in 1860, the year of the ‘Manifesto’ against the New Germans, when he was so aware of dividing paths and the discarding of old values, suggests a polemical ring, an extreme statement of principle. In reality he was expressing faith in a set of values: of a particular melodic character, of formal clarity, of the direct relation between melodic and poetic structure. But his relationship with them needed flexibility to be of use to a creative composer. Brahms’s later original settings of some of the folk-song texts would show him breaking down the stylised form. In ‘Spannung’ Op. 84 No. 5, using the text ‘Guten Abend, Guten Abend, mein tausiger Schatz’ (No. 4 of the Deutsche Volkslieder ), the six verses are set with a contrast melody for verse 3, a variant of the original in the major mode in verse 6, as well as developing keyboard figuration, where the setting of the original melody only varies the accompaniment in verses 4–6. In ‘Dort in den Weiden steht ein Haus’ Op. 94 No. 7 (No. 31 of the Deutsche Volkslieder ), he extends the first cadence from a 2/4 to a 3/4 bar to shift the whole emphasis of the words to the end of the line (he also omits the structural repetition in the original, to give an entirely different mood), as well as varying the accompaniment for verse 3. Sometimes his melody is a response to a pre-existent melody: the famous ‘Wiegenlied’ Op. 49 No. 4 incorporates another lullaby known to and sung by its dedicatee, Bertha Faber (formerly Bertha Porubszky); thus his melody extends an original by contrapuntal or complementary means.

The folk idiom remained central to a vast part of Brahms’s melodic language. In the songs there is an especially large stock of folk-like melodies, or melodies of a rounded character which clearly relate to them. An example of the first,‘Der Schmied’ (‘The Smith’) Op. 19 No. 4, is subtly distinguished from the melodies in the Deutsche Volkslieder by its leaping chordal shape and extended cadence. ‘Vergebliches Ständchen’ Op. 84 No. 4 includes internal repetition in voice and piano; ‘Sonntag’ Op. 47 No. 3 plays on repetition to give a much more extended structure than is implied by the simple opening figure. More distantly, a folk-like quality remains in many Brahms songs which are of a more expansive kind, with more developmental melodies and with freer, more active and elaborate accompaniments. One might take such examples as ‘Sommerabend’ Op. 85 No. 1, ‘Dein blaues Auge’ Op. 59 No. 8, ‘Auf dem See’ Op. 106 No. 2 and ‘Von waldbekränzter Höhe’ Op. 57 No. 1, where basic scalic and chordal patterns still lie at the root. Brahms also wrote in a very strict ‘altdeutsch’ chorale style, entirely syllabic and scalic with stark, root-position accompaniments, in settings for solo voice and piano which also appear for four-part chorus: ‘Vergangen ist mir Glück und Heil’ Op. 48 No. 6; ‘Ich schell mein Horn ins Jammerthal’ Op. 43 No. 3.

Yet the world of folk-song, however subtly extended, was clearly very limiting to a composer with Brahms’s pronounced lyrical gifts, wide stylistic range and love of structural variation. For all his use of folk-song, Brahms had long shown a capacity for a wider range, and some of his earliest songs are highly dramatic, almost expressionistic: his earliest known song, ‘Heimkehr’ Op. 7 No. 6 (1850), and the second setting of ‘Liebe und Frühling’, Op. 3 No. 3, are both almost like operatic scenas , with dramatic piano introductions and throbbing accompaniments to the vocal line. Brahms’s first published song, ‘Liebestreu’ Op. 3 No. 1, controls its powerful expression by a strong canonic movement between the voice and the bass part of the piano. Such songs had existed side by side with the most intimate types from the first (‘Heimkehr’ is preceded in Op. 7 by the song ‘Volkslied’ and the folk-song setting ‘Trennung’). The stylistic range of the Op. 32 songs to texts by Platen and Daumer, and the Magelonelieder Op. 33, all written between 1859 and 1862, show no desire to restrict the dramatic aspect; on the contrary. But it is now given a new character, with a more rounded melody and a more supportive than illustrative accompaniment, and the structure is becoming more extended.

Given Brahms’s ideals and stylistic preferences, what were the issues governing his mature settings? Essentially, he sought to expand the strophic type into varied strophic forms and to adapt those to a wider stylistic range. This did not happen chronologically (from one type to another in one period): rather, a constant synthesis was at work between different types throughout, with the elements always drawn into an integrated whole. The vehicle was both musical and poetic: on the one hand, the adaptation of the musical form to provide greater expressive capacity; on the other, the choice of interesting poetic forms which would determine a comparable musical response. This essay presents selected examples to illustrate the broader trends in the output as a whole.

Modified strophic form

The strength of the modified strophic form lay in its focus – one sentiment embodied in a self-sufficient principal melody, yet with opportunities for musical variation mirroring subtle changes in either the poetic content or its metrical structure. It offered many musical possibilities, ranging from the slight variation of a repeated verse through more extensive recomposition to alternation with a contrasted verse (A A B A), or combinations of these patterns. Only slight irregularity in the disposition of a poetic stanza itself was necessary to give opportunities for striking musical variation and development. And musical variation of an anticipated formal norm might also serve to reveal a meaning more fully: to reveal humour, pathos, irony, for example. The following examples trace some typical stages of variation of the strophic folk-like type as demonstrated in Brahms’s 49 Deutsche Volkslieder and in his original settings of folk poems.

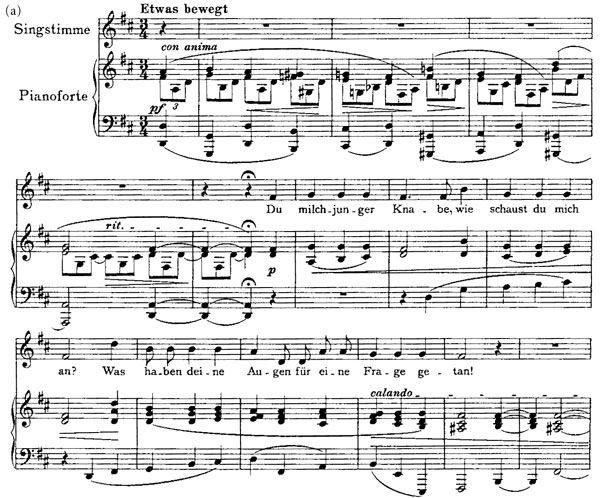

A first stage can be seen in the setting of Gottfried Keller’s ‘Therese’ Op. 86 No. 1. 11 Here Brahms chooses a folk-like melodic idiom for the stylised folk-like poem, in which an experienced older woman gently rebukes the advances of an amorous youth and teaches him a lesson. The style is conversational, its stepwise questioning mode similar to the earlier folk-song setting ‘Trennung’ Op. 7 No. 4 with its similarly prescribed vocal range and varied third verse. It is in three equal strophes; in strophes 1 and 2 she demands what he wants of her, though in a coquettish, knowing way; in verse 3 she sends him away to look in an old sea shell and find its answer.

|

Du milchjunger Knabe, |

You young, young boy, |

|

|

Wie schaust du mich an? |

Why do you look at me so? |

|

|

Was haben deine Augen |

What are you asking, |

|

|

Für eine Frage getan! |

What would you know! |

|

|

Alle Ratsherrn in der Stadt |

All the councillors of the town |

|

|

Und alle Weisen der Welt |

And the wisest men on earth |

|

|

Will remain dumb at the question |

||

|

Deine Augen gestellt! |

I see in your eyes |

|

|

Eine Meermuschel liegt |

A seashell lies |

|

|

Auf dem Schrank meiner Bas, |

In my cousin’s cupboard; |

|

|

Da halte dein Ohr dran |

Put your ear to it, |

|

|

Dann hörst du etwas! |

Perhaps it will tell! |

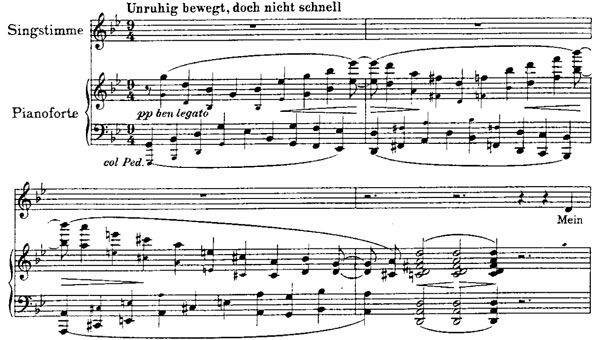

The syllabic pattern of each stanza is similar and the poem could therefore be set in a repetitive form. But Brahms adapts both the vocal idiom and the strophic form to bring out the meaning better. The melody lies between the third and sixth degrees of the scale and never resolves to the tonic; stanzas 1 (Example 9.1a

) and 2 both end on the third, which Brahms harmonises as III![]() (F

(F![]() in D major), followed by a composed pause – an augmented rhythm for the cadence: all these features create suspense. But stanza 3 (Example 9.1b

) is totally transformed musically. It is marked slower, ‘etwas gehalten’, with much softer dynamics to emphasise the radical harmonic shift, whereby the F

in D major), followed by a composed pause – an augmented rhythm for the cadence: all these features create suspense. But stanza 3 (Example 9.1b

) is totally transformed musically. It is marked slower, ‘etwas gehalten’, with much softer dynamics to emphasise the radical harmonic shift, whereby the F![]() chord now serves as the dominant of B major (D major’s submediant major), and the melodic shift, whereby the newly fashioned melody with wider intervals, beginning with rising fourth and falling octave, makes the response. In repeating this melody on the tonic after expressive chromatic movement in the bass and middle parts, the melody does not finally end on the tonic; only the piano, shadowing the material of the introduction, really concludes the song. Expansion in the piano part before this final phrase further secures the expressive goal. This final phrase and piano conclusion show an unusual balance between vocal and pianistic claims within the norms of Brahms’s style, especially in such a folk-like vein.

chord now serves as the dominant of B major (D major’s submediant major), and the melodic shift, whereby the newly fashioned melody with wider intervals, beginning with rising fourth and falling octave, makes the response. In repeating this melody on the tonic after expressive chromatic movement in the bass and middle parts, the melody does not finally end on the tonic; only the piano, shadowing the material of the introduction, really concludes the song. Expansion in the piano part before this final phrase further secures the expressive goal. This final phrase and piano conclusion show an unusual balance between vocal and pianistic claims within the norms of Brahms’s style, especially in such a folk-like vein.

Example 9.1 ‘Therese’ Op. 86 No. 1

(a) verse 1, bars 1–14

(b) verse 3, bars 25–39

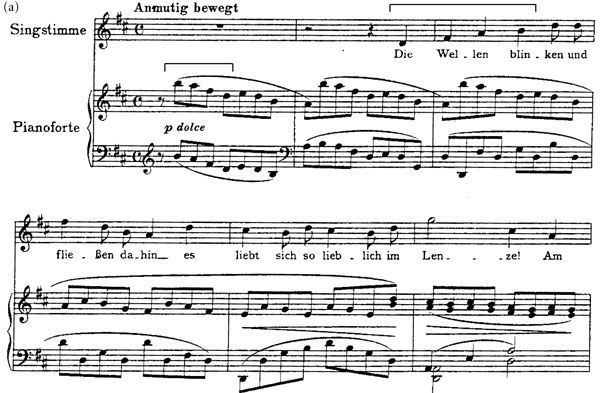

The idiom of the setting of Heine’s ‘Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze’ Op. 71 No. 1 12 is, by comparison, of a more open-air, triadic type, in accordance with its narrative topic. It uses a more elaborate folk idiom in its expanded range (spanning a tenth in the mirror-like opening arpeggiac phrase) and in its onward development of an essentially alternating musical design; it greatly extends its basic materials in projecting a small drama around the stylised rustic scene. The poem tells of a hopeful girl making garlands by the river in springtime. To whom will she give them? A fine rider comes by, sporting a plume, but he passes on, leaving her bereft. The refrain, repeated again in the last line, ‘Love is so lovely in Springtime’ gives the poem an ironical, bittersweet quality.

|

Die Wellen blinken und fließen dahin – |

The waves gleam and flow by – |

|

|

Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze! |

Love is so lovely in Springtime! |

|

|

Am Flusse sitzet die Schäferin |

The shepherdess sits by the riverside |

|

|

Und windet die zärtlichsten Kränze. |

And weaves the loveliest garlands. |

|

The buds, the water, the fragrance, the bloom – |

||

|

Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze! |

Love is so lovely in Springtime! |

|

|

Die Schäferin seufzt aus tiefer Brust: |

The shepherdess gives the deepest sigh: |

|

|

‘Wem geb’ ich meine Kränze?’ |

‘To whom shall I give my garlands?’ |

|

|

Ein Reiter reitet den Fluß entlang; |

A rider rides by the riverside; |

|

|

Er grüßet so blühenden Mutes! |

He greets her so boldly in passing! |

|

|

Die Schäferin schaut ihm nach so bang, |

The shepherdess watches, her heart so sore, |

|

|

Fern flättert die Feder des Hutes. |

The plume of his hat disappearing. |

|

|

Sie weint und wirft in den gleitenden Fluß |

She weeps, and in the flowing stream, |

|

|

Die schönen Blumenkränze. |

Throws her beautiful garland. |

|

|

Die Nachtigall singt von Lieb und Kuß – |

The nightingale sings of love and embrace – |

|

|

Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze! |

Love is so lovely in Springtime! |

Brahms modifies the strophic setting in three ways: by extending the strophe itself through repetition; by providing a contrast verse setting,and by extensive melodic and harmonic recomposition of the last verse: thus the pattern is A A B1 A1.Though the poem has balancing four-line stanzas, Brahms concludes his verse with a repetition of the text to extend the phrase length to 2+2+2+3 bars and thus to emphasise the end of each stanza. Following the sense of the poem, the same music is used for stanzas 1 and 2. In stanza 3, the image of the galloping horse is reflected in a more strident melody, with a triplet piano figure and a shift to the mediant (F![]() in D major), though continuing to develop earlier material. Stanza 4 (Example 9.2b

) further develops the opening theme through harmonic variation,though it moves firmly to the subdominant G major for the third line at the image of the nightingale, before coming to a robust new conclusion of the theme, the piano postlude dying away (perhaps with the vanishing rider). The change of mood in verse 4 is obviously intended to express irony: Brahms had apparently sought to capture this in the redirection of the harmony, the modulation through G and the almost overcheerful, too culminative conclusion. Whether he has done so is perhaps doubtful. At least he seems more intent on bold humour than irony through these means.Viewed differently, however, the whole setting could be taken as ironical, given the obvious relation of the opening theme to the inverted and repeated figure in the introduction (Example 9.2a

) which seems wilfully apparent in octaves, and to impart a false sense of innocence to the confident vocal idiom.

in D major), though continuing to develop earlier material. Stanza 4 (Example 9.2b

) further develops the opening theme through harmonic variation,though it moves firmly to the subdominant G major for the third line at the image of the nightingale, before coming to a robust new conclusion of the theme, the piano postlude dying away (perhaps with the vanishing rider). The change of mood in verse 4 is obviously intended to express irony: Brahms had apparently sought to capture this in the redirection of the harmony, the modulation through G and the almost overcheerful, too culminative conclusion. Whether he has done so is perhaps doubtful. At least he seems more intent on bold humour than irony through these means.Viewed differently, however, the whole setting could be taken as ironical, given the obvious relation of the opening theme to the inverted and repeated figure in the introduction (Example 9.2a

) which seems wilfully apparent in octaves, and to impart a false sense of innocence to the confident vocal idiom.

Example 9.2 ‘Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze’ Op. 71 No. 1

(a) verse 1, bars 1–6

(b) retransition to verse 4, modulation to G major and conclusion, bars 34–52

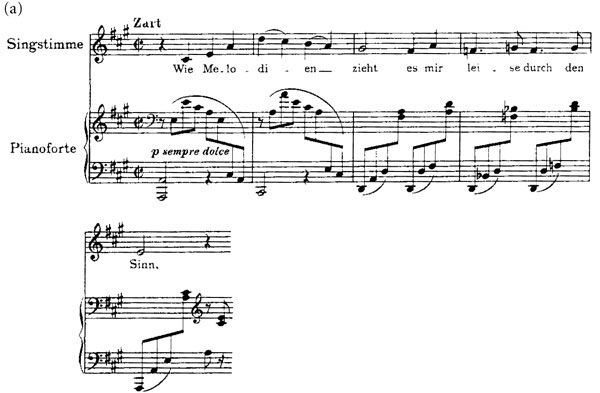

In the setting of Klaus Groth’s ‘Wie Melodien zieht es mir’ Op.105 No. 1, 13 another strophic structure is provided with a very different kind of melody: not an elaborated folk type, but a chordal opening (Example 9.3a ) treated in an essentially instrumental way (the same basic contour reappears as the second subject of the A major Violin Sonata Op.100) and standing apart from the essentially repetitive or alternating material of the previous examples. Brahms adopted this musical character because of the subject of the poem, which evokes the power of music to arouse feeling which mere words cannot express:

|

Wie Melodien zieht es |

It runs, like melodies |

|

|

Mir leise durch den Sinn, |

Quietly through my senses, |

|

|

Wie Frühlingsblumen blüht es |

It blossoms like Spring flowers |

|

|

Und schwebt wie Duft dahin. |

And clings there like perfume. |

|

|

Doch kommt das Wort und faßt es |

Then a word comes to hold it |

|

|

Und führt es vor das Aug’, |

And brings it in front of my eyes |

|

|

Wie Nebelgrau erblaßt es |

And it dispels like fog |

|

|

Und schwindet wie ein Hauch. |

And vanishes like a sigh. |

|

|

Und dennoch ruht im Reime |

And, for all that, in this rhyme |

|

|

Verborgen wohl ein Duft, |

There lies hidden at least a scent of it, |

|

|

Den mild aus stillem Keime |

Which, from a silent bud, is gently |

|

|

Ein feuchtes Auge ruft. |

Coaxed by a tearful eye. |

The three stanzas of 7 6 7 6 syllables could again be set to a repetitive structure, a b a b for each stanza. However, this would be to diminish the poem’s meaning, which grows in interest, purpose and focus as it unfolds

towards the conclusion. Likewise, the simple rhythmic scheme of the verse gives insufficient opportunity to symbolise the expressive content in the music. Brahms follows the natural rhythms for most of the verse, lines 2–4; but notably transforms the opening line of 7 syllables to an equivalent of 10 syllables in length by doubling the length of the syllables ‘di-en zieht’. Not only this, but he places the opening three syllables as an anacrusis to these extended syllables. The reason is obviously to attract attention to the key word by exposing it, and likewise the parallel words in verses 2 and 3, ‘Wort’ and ‘Reime’. Additionally, Brahms repeats the last line so that, with the piano postlude, a total of twelve bars results where eight would have been predicted, to make a more conclusive ending. The settings of the second and third verses vary this model to reflect the comparison presented by the poet. In the second verse, the music is led from the second line into the relative minor (F![]() minor) via the subdominant (D). The lowering of the melodic G from G

minor) via the subdominant (D). The lowering of the melodic G from G![]() at ‘schwindet wie ein Hauch’ (‘vanishes like a sigh’) immediately reflects the textual contrast. In verse 3, the recomposition is delayed a little later to take the music into F major, the lowered VI degree, though its direct resolution onto the dominant and closure is beautifully delayed by its acting as dominant to B

at ‘schwindet wie ein Hauch’ (‘vanishes like a sigh’) immediately reflects the textual contrast. In verse 3, the recomposition is delayed a little later to take the music into F major, the lowered VI degree, though its direct resolution onto the dominant and closure is beautifully delayed by its acting as dominant to B![]() , from which the music returns chromatically into the tonic: then the tonic returns with added freshness, including an emphasis on the word ‘feuchtes’ (‘tearful’) by a melisma as part of a now expanded response which takes in lines 3 and not just 4 to make sixteen bars from twelve (Example 9.3b

). Thus the composer achieves a remarkable diversity of harmonic resolution in such a short space.

, from which the music returns chromatically into the tonic: then the tonic returns with added freshness, including an emphasis on the word ‘feuchtes’ (‘tearful’) by a melisma as part of a now expanded response which takes in lines 3 and not just 4 to make sixteen bars from twelve (Example 9.3b

). Thus the composer achieves a remarkable diversity of harmonic resolution in such a short space.

Example 9.3 . ‘Wie Melodien zieht es mir’ Op. 105 No. 1

(a) verse 1, bars 1–5

(b) verse 3, complete, bars 28–46

To a second category belong settings which modify the strophic form through metrical factors within the poetry itself, rather than by musical means alone. Several stages of complexity can again be observed.

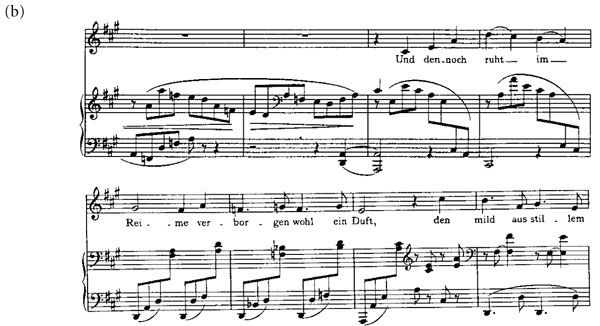

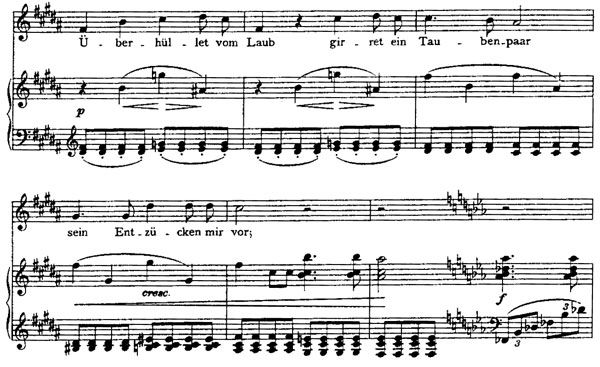

In Hölty’s ‘Die Mainacht’ Op. 43 No. 2, 14 the vocal style is again close to a folk type, the opening built on the decoration of a triad with answering phrases a b a b, though one destined to develop more dramatically at its close. Brahms gave this song as an example of how an idea, once discovered, could develop unconsciously over time to reveal its full potential in the completed song. The poem evokes the poet’s loneliness, sharpened against the idyllic moods of nature – the silvery moon, the trembling leaves, the warbling nightingales, and symbolised in a pair of cooing doves. Where will the poet find balm for his tears?

|

Wann der silberne Mond |

When the silvery moon |

|

|

Durch die Gesträuche blinkt, |

Shines through the trembling leaves, |

|

|

Und sein schlummerndes Licht |

And its slumbering light |

|

|

Über den Rasen streut, |

Spreads softly o’er the grass, |

|

|

Und die Nachtigall flötet, |

And the nightingale warbles |

|

|

Wandl’ ich traurig von Busch zu Busch. |

I wander sadly from glade to glade. |

|

|

Uberhüllet vom Laub |

Roofed in with foliage |

|

|

Girret ein Taubenpaar |

A pair of doves coo |

|

|

Sein Entzücken mir vor; |

Their rapture at me, |

|

|

Aber ich wende mich, |

But I turn away, |

|

|

Suche dunklere Schatten, |

Seek deeper shadows |

|

|

Und die einsame Träne rinnt. |

To be with my tears alone. |

|

|

Wann, O lächelndes Bild, |

When, O smiling image |

|

|

Welches wie Morgenrot |

That comes like the sunrise |

|

|

Durch die Seele mir strahlt, |

Flowing through my soul, |

|

|

Find’ ich auf Erden dich? |

Will I find you on earth? |

|

|

Und die einsame Träne |

And the lonely tear |

|

|

Bebt mir heißer die Wang’ herab. |

Flows hotter down my cheek. |

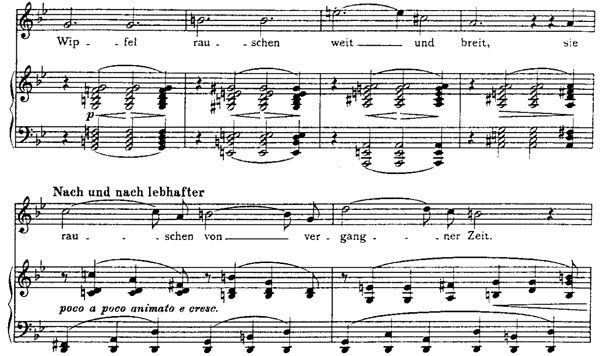

Here four equal lines are followed by successively extended fifth and sixth lines in the syllabic scheme 6 6 6 6 7 8, thus again placing a focus at the end of the verse. Though there is no actual rhyme scheme between them, they fall into complementary pairs in verses 1 and 3 and Brahms reflects this pattern in his melody, with an cadential augmentation to conclude the verse. In verse 2 (Example 9.4a ), however, the stanzaic structure demands musical variation. Here the six lines are structured as two pairs of three lines as, in a changed image, the doves distract the poet with their intimacy and he turns away from them. The music mirrors this, moving into B major, enharmonically reached from the minor chord on E , but the ‘turning to deeper shadows’ brings a declamatory re-transition to the tonic and a massively elaborated cadence to accommodate the melisma on ‘Träne’. This wonderful new phrase is then repeated twice in verse 3, which unites the music of verse 1, first part, and verse 2, second part. When ‘Träne’ recurs, reaching its goal through a lowered II degree in the progression II–v–i, the melisma is now given to the word ‘Wang’ (‘cheek’), so that the textual intensification is exactly mirrored in the music (Example 9.4b ).

Example 9.4 ‘Die Mainacht’ Op. 43 No. 2

(a) verse 2, bars 15–32

Like ‘Die Mainacht’, Brahms’s setting of Daumer’s ‘Wir wandelten . . .’ (‘We walked . . .’) Op. 96 No. 2 15 also uses a chordal pattern; however, the melody is not as independent, relying on the piano for its completion, and the irregularity of the stanzaic structure prompts further the individuality of the setting. The text describes the recollection of unspoken thoughts by a lover, who has questioned, but remained in a state of bliss.

|

Wir wandelten, wir zwei zusammen, |

We walked, we two together. |

|

|

Ich war so still und du so stille; |

I was so still and you so still; |

|

|

I would give much to know, |

||

|

Was du gedacht in jenem Fall. |

What you were thinking at that time |

|

|

Was ich gedacht – unausgesprochen |

What I was thinking – unuttered |

|

|

Verbleibe das! Nur Eines sag’ ich: |

Let it remain! Only one thing I say: |

|

|

So schön war Alles, was ich dachte, |

It was all so lovely, that I thought, |

|

|

So himmlisch heiter war es all. |

So celestially serene it all was. |

|

|

In meinem Haupte die Gedanken, |

The thoughts in my head, |

|

|

Sie läuteten wie gold’ne Glöckchen; |

They chimed like golden bells; |

|

|

So wundersüß, so wunderlieblich |

So passing sweet, so passing lovely |

|

|

Ist in der Welt kein and’rer Hall. |

In all the world there was no other sound |

The irregularity of the phrasing arises from the metre and stress, with lines of 9 9 9 8 syllables, the first line requiring musical extension because of the natural stress on ‘zusa mmen’. The stress becomes the focus of the setting of line 1, which takes 2½ bars. Since it does predict a responding vocal phrase, Brahms uses the piano’s developmental accompaniment to link to the second line, of basically the same length: ‘-sammen’ balanced by ‘stille’. As in ‘Die Mainacht’, the meaning of strophe 2 determines an internal variation in its structure; lines 1 and 2 are continuous, with a separate thought, ‘Nur Eines sag ich’, ending line 2 and preparing for its consequent: ‘So schön war Alles . . .’ Brahms reflects this in his setting by presenting an entirely new melody for the latter in a new key and preparing it by the repetition of the former in augmentation for emphasis (one bar in 3/2). This thought continues until the end of verse 3 in the poem. Brahms satisfies the requirements of his strophic form by returning to the opening melody at line 3 of verse 3 ‘So wundersüß . . .’, but reflects the continuity by accommodating the quaver figure which he has subsequently introduced into the vocal part (perhaps to evoke the bells of the text). Thus, one melody embodies the basic thought, but the changing details are also accommodated.

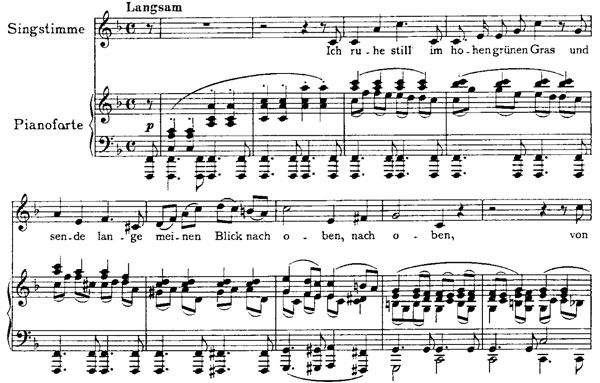

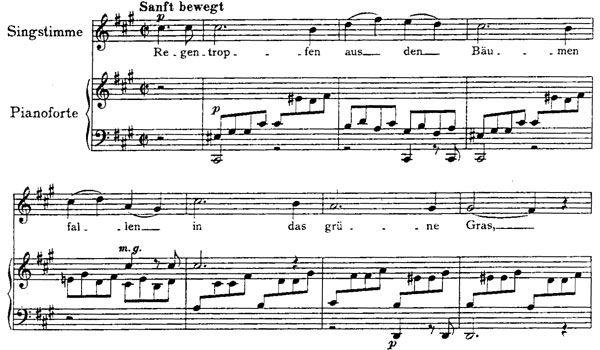

In his setting of Hermann Allmers’s ‘Feldeinsamkeit’ as Op. 86 No. 2, 16 Brahms treats the chordal idiom in a different way. Rather than essentially articulating a chordal progression through balancing answering phrases, he here focuses all attention on the constituent intervals within the opening octaves themselves, as the starting point of a melody of extraordinary focus, manipulating them to telling effect (Example 9.5 ). The melody is now completely removed from any suggestion of folk-like origin. Equally its character permits a remarkably simple harmonic progression for the verse, with a move to the dominant and quick return to a long tonic in the second half of the stanza. Thus, mirroring its text, it stands apart from other melodic types. The musical texture is grounded in the quiet throbbing of the piano bass pedal points. Static chords float above, continually fluctuating like the changing cloud shapes the poet watches so raptly. This organic character develops further in verse 2 with subtle internal modulations to intensify the words. The poem describes the vast peace experienced by one lying and gazing at the boundless sky, when time and identity are suspended.

Example 9.5 ‘Feldeinsamkeit’ Op. 86 No. 2, verse 1, bars 1–9

|

Ich ruhe still im hohen grünen Gras |

I lie still in the high green grass |

|

|

Und sende lange meinen Blick nach oben, |

And gaze raptly upwards, |

|

|

Von Grillen rings umschwirrt ohn’ Unterlaß, |

Crickets chirp around unceasingly, |

|

|

Von Himmelsbläue wundersam umwoben. |

The blue of the sky weaves wondrously around. |

|

|

Die schönen weißen Wolken zieh’n dahin |

The beautiful white clouds pass by |

|

|

Durch’s tiefe Blau, wie schöne stille Träume; |

Through the deep blue, like beautiful quiet dreams |

|

|

Mir ist, als ob ich längst gestorben bin |

It is as though I had long been dead |

|

|

Und ziehe selig mit durch ew’ge Räume |

And was passing with them through eternal space. |

The rhythm of the four-line stanza alternates pairs of ten and eleven syllables (10 11; 10 11). The pattern also contains end-rhyme between lines 1 and 3 and 2 and 4 – ‘Gras/-laß; ‘oben’/‘-woben’, in each verse. Brahms might therefore have set it in a musical pattern a b a b for each stanza. However, this would have been less effective than the structure he eventually built, which provides a good illustration of music’s need of greater space to capture mood than the spoken poem, where meaning can be imparted by the merest inflection of the voice. A rhythmic balance of the first line would have tied the poem unduly. Brahms’s wonderful melisma at ‘meinen Blick nach oben’ requires a balancing response as the music comes to the dominant. Thus extended (2+2 = 4) the second half of the verse places emphasis on the fourth line with a new figure, thus requiring balance by extension (2+2+4) to make a balance of 6+8, a total of fourteen bars (with an interpolated piano bar) where the opening two-bar phrase might have predicted only eight. In verse 2 the most beautiful harmonic recomposition of the material and extension of the vocal line prolongs the length to sixteen bars.

Finally, the case of Brahms’s setting of Daumer’s ‘Wie bist du, meine Königin’ Op. 32 No. 9 17 shows the strophic form with stepwise, rounded melody at its farthest remove from a folk-like source. The melody stands as apart from most examples as the previous song in its ‘artful’ character: ongoing and continuous (though not in the instrumental, developmental sense) and obviously conceived in equally close association with the piano part, and here avoiding the strong chordal progressions that underpin more straightforward melodies in favour of inversion-based progressions and stepwise part-movement (Example 9.6 ). These arise in response to the poem, which offers no strong accentual model and cultivates a rapt and focused mood. It is an ecstatic declaration of love and devotion to an idealised woman, who is compared to springtime and the freshest flowers, and who represents coolness and balm which even nullifies the bitterness of death:

Example 9.6 ‘Wie bist du meine Königin’ Op. 32 No. 9, verse 1, bars 1–24

|

Wie bist du, meine Königin, |

How wondrous art thou, my queen |

|

|

Durch sanfte Güte wonnevoll! |

Through your soft goodness! |

|

|

Du lächle nur – Lenzdüfte weh’n |

You need only smile – and spring fragrances |

|

|

Durch mein Gemüte wonnevoll! |

Waft through my spirit – wondrously! |

|

|

Frisch aufgeblühter Rosen Glanz, |

The brightness of fresh-blooming roses |

|

|

Vergleich’ ich ihn dem deinigen? |

Shall I compare it to your brightness? |

|

|

Ach, über alles was da blüht, |

Ah, above all that blooms |

|

|

Ist deine Blüte wonnevoll! |

Is your bloom wondrous! |

|

|

Durch tote Wüsten wandle hin, |

Wander through dead wastes |

|

|

Und grüne Schatten breiten sich, |

And green shadows will spread themselves, |

|

|

Ob fürchterliche Schwüle dort |

Even if fearful sultriness reigns endlessly, |

|

|

Ohn’ Ende brüte, wonnevoll |

Wondrously. |

|

|

Laß mich vergeh’n in deinem Arm! |

Let me die in your arms! |

|

|

Es ist in ihm ja selbst der Tod, |

Even death itself, |

|

|

Ob auch die herbste Todesqual |

Though the sharpest pangs pierce the heart, |

|

|

Die Brust durchwüte, wonnevoll! |

Comes wondrously! |

The poetic stanza is of four lines of eight syllables (8 8 8 8) falling into two parts: lines 1–2 and 3–4 (though in verse 1, less regularly: 1–2, ½, 1½). There is no consistent internal rhyme: rather, the distinctive rhyming feature is the final word ‘wonnevoll’ – ‘joyously’, a resonant word which recurs in each strophe as its goal. This word becomes the focus of Brahms’s setting. He intensifies the continuity of lines 3–4 of each stanza by shortening the note values of the third line to enable its expansive statement and repetition in line 4, in which the piano plays an essential part in balancing the phrase by anticipating to or responding to the word. The natural stress on ‘wonnevoll’ requires that the whole melody possess a downbeat character, though it fits verses 2 and 4 better than 1 and 3 (the more natural accentuation is ‘Wie bist du’; ‘Du lä chle nur’). Lines 3 and 4 come out as an eight-bar section if the insertion of ‘wonnevoll’ in the piano is omitted. This insertion is also a feature of lines 1–2, enabling the voice to echo the piano, thus making a six-bar setting of lines 1–2, where five bars could have served, as is the case in the piano introduction based on the same material (repeated as a postlude at the end of verse 1). Verse 3 is set separately as a variant to capture the darker colouring of the text. Here the rhythm is stretched further by syncopated augmentation at ‘Ohn’ Ende’ to make five bars of the original four, whilst the recomposition of the material involves an additional repetition of ‘wonnevoll’. The setting has been criticised for its ‘faulty’ scansion. Yet a setting in the alternative metre of 4/4, which reflects the verbal stresses more closely, would tie the rhythm down too much for the sense of suspension and wonder which is the poem’s essence. Brahms’s ravishing melody in 3/4 embodies an aesthetic choice, in focusing on mood and distributing the accents sufficiently evenly without undue stress to give the singer every opportunity to inflect them and communicate the sense. All the same, the different stress which has thereby to be given to the same key word (‘wonnevoll’ having to take an end stress where it occurs at the end of line 2 in strophe 1) shows the sacrifice Brahms occasionally had to make in the service of his larger aesthetic.

Instrumental and dramatic songs

A composer of Brahms’s stylistic and formal range could hardly have restricted himself in over 200 original songs to essentially rounded and syllabic melody. Despite the preponderance of such types, there exist many which explore much wider stylistic territory. Two types stand out: songs of an instrumental melodic character, and songs of a dramatic character.

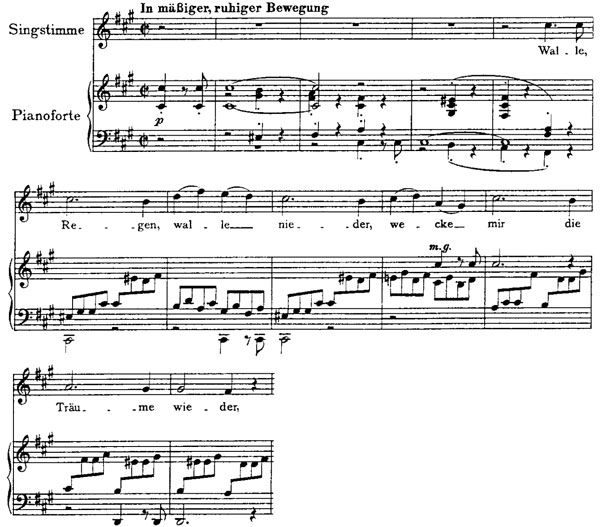

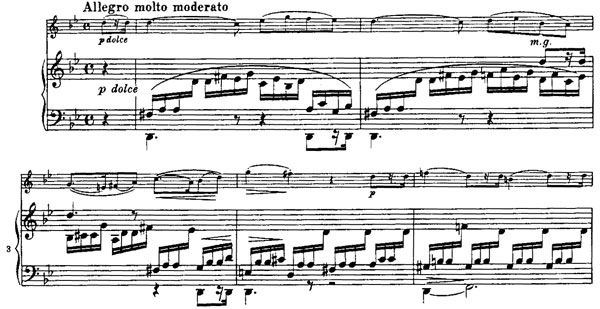

Of the instrumental types, the most striking example comes in the intimate relationship between the third movement of the Violin Sonata in G Op. 78 and the settings of Klaus Groth’s poems ‘Regenlied’ and ‘Nachklang’ Op. 59 Nos. 3 and 4. The sonata movement is a rondo, its first theme a continually evolving sixteen-bar structure with a continuous semiquaver accompaniment (Example 9.7c

). Both songs share their opening four-bar phrase with the sonata theme. The first, ‘Regenlied’ (Example 9.7a

), uses its rhythm and opening pitch repetition (three C![]() s) as the motive of a four-bar introduction. Thereafter it is structured as a sixteen-bar continuous melody to an eight-verse strophic text, though it stays closer to the opening phrase than does the sonata theme, which develops a new figure based again on the memorable opening rhythm. The text describes the memories of childhood evoked by the patter of rain on the window pane (which is seemingly reflected in the animated accompaniment). The second verse takes a different route, its latter part developing widely and concluding with an augmented cadence to make twenty bars from the earlier sixteen. The growing intensity of the memories extends the treatment for stanzas 3 and 4 with a new and more truly instrumental melody, ending with further repetition and cadential augmentation to make twenty-four bars. Stanzas 5 and 6 offer a new melody in a contrasting key and metre, until a return of the music of lines 1 and 2. Thus, the six stanzas embody the continuous principle of the instru-mental rondo movement with quite independently generated material

within a large A B A scheme reflecting the poem. The following, second setting of a similar subject – ‘Nachklang’ (‘Echo’) Op. 59 No. 4 (Example 9.7b

) – reworks the material yet again for a shorter poem. But the brevity includes greater formal subtlety, the irregular two stanzas permitting a freer phraseology in which the piano shares as an integral partner, the second stanza extended from sixteen to twenty-five bars, including piano interpolation. It begins, like the sonata movement, with no introduction.

s) as the motive of a four-bar introduction. Thereafter it is structured as a sixteen-bar continuous melody to an eight-verse strophic text, though it stays closer to the opening phrase than does the sonata theme, which develops a new figure based again on the memorable opening rhythm. The text describes the memories of childhood evoked by the patter of rain on the window pane (which is seemingly reflected in the animated accompaniment). The second verse takes a different route, its latter part developing widely and concluding with an augmented cadence to make twenty bars from the earlier sixteen. The growing intensity of the memories extends the treatment for stanzas 3 and 4 with a new and more truly instrumental melody, ending with further repetition and cadential augmentation to make twenty-four bars. Stanzas 5 and 6 offer a new melody in a contrasting key and metre, until a return of the music of lines 1 and 2. Thus, the six stanzas embody the continuous principle of the instru-mental rondo movement with quite independently generated material

within a large A B A scheme reflecting the poem. The following, second setting of a similar subject – ‘Nachklang’ (‘Echo’) Op. 59 No. 4 (Example 9.7b

) – reworks the material yet again for a shorter poem. But the brevity includes greater formal subtlety, the irregular two stanzas permitting a freer phraseology in which the piano shares as an integral partner, the second stanza extended from sixteen to twenty-five bars, including piano interpolation. It begins, like the sonata movement, with no introduction.

(a) ‘Regenlied Op. 59 No. 3, bars 1–12

(b) ‘Nachklang’ Op. 59 No. 4, bars 1–8

(c) Violin Sonata in G major Op. 78, movement 3, bars 1–9

As has been noted, the song ‘Wie Melodien zieht es mir’ Op. 105 No. 1 relates closely to the second subject of the Second Violin Sonata in A Op. 100. The relation is not as literal as in the Op. 78 movement, but is rather an identity of melodic shape between the opening phrases of song and sonata subject, unmistakable despite rhythmic dissimilarities. The sonata theme is again of sixteen bars’ length; the song stanza is of twelve bars, though again of continuously evolving character.

In the Two Songs for Alto with Viola Op. 91, the relation of instrumental and vocal idioms is made tangible in two songs with voice and instrument on equal terms, the alto voice simulating and complementing the viola idiom. The second song offers a further synthesis of influences: it opens with a purely instrumental stanza to represent the text, the viola playing the well-known folk-song lullaby ‘Lieber Josef, Josef mein’, depicting the sleeping Jesus (Brahms placed the text under the melody in the score). The remaining seven stanzas of the eight-stanza poem explore the imagery of swaying palms to symbolise his passion to come. The voice enters in stanza 2 with a theme drawn from the opening of the folk-song by augmentation and inversion, the viola sharing with the piano more animated movement. In stanza 3 the voice begins to share this movement, conversing with the piano and viola in animated trio style and modulating through A major before restoring the tonic for the second part of its first-stanza theme (‘stille die Wipfel’). Stanza 4 brings a more intense tone – a new metre, melody and texture at the prospect of the burden to come – but soon returns to the musical succession of stanzas 2 and 3, and the instrumental cradle song provides the coda, mirroring the introduction. Op. 91 No. 1 is a hymn at twilight to peace by Friedrich Rückert, four stanzas in which the poet reflects on the futility of human assertion in the presence of the stillness of nature. The instruments again take the first section, though with no associated text, and the first vocal stanza is again a counterpoint or complement to the repeating instrumental part. In stanza 3, the voice takes the viola part of the opening and the viola counterpoints with a much more florid semiquaver pattern. As in the following song, stanza 4 presents stark contrast, here of tonality and mood; however, the opening material is quickly restored in the major, though not the key signature, which reappears only with the music of stanza 2 over a dominant pedal, followed by that of stanza 3 for the completion of the setting. Thus both settings involve the sharing of material, yet also the generation of new material specific to the medium of voice, viola and piano.

In other later songs without such instrumental participation, Brahms employs an instrumental idiom in the voice or piano or both. The example most closely related to those just discussed is a setting of Candidus’s ‘Alte Liebe’ Op. 72 No. 1. Here the continuously evolving melody in 6/4 time recalls the rhythmic pattern of the first movement of the Op. 78 sonata in its opening dotted minim chords and distinctive anacrusis, though the range is for the viola, not the violin. The melody is constrained in its growth by the poetic strophe of four lines (7 6 7 6), but its potential is developed in the following four stanzas of the 5-stanza poem: the return of spring reawakens bitter feelings of a lost earlier love; the poet feels contact, hears sounds, smells scents from his memory, but cannot escape his thoughts. In the musical form, each stanza grows from the last, shared rhythms gaining new shapes and original shapes being worked into new contexts with wider modulation to evoke the growing memories, before the return of the opening and the source of bitterness – the beloved – to make an overall pattern for the five stanzas of A – A1 – A2 – development – A. The song could certainly be played as an effective viola solo.

In other songs, the instrumental role is given to the piano, the voice adding a commentary as a variant, and thus sharpening the distinction. One of the most striking is the setting of Heine’s ‘Meerfahrt’ (‘Sea Journey’) Op. 96 No. 4, where the piano right hand has a bold venturesome melody of instrumental character – it could be a passage for cellos or solo horn if orchestrated – which evokes, with its strident left hand accompaniment and uneven, seamless phrasing, a boundless infinitude of sea, on which an unheeding couple are adrift: the 14-bar introduction divides memorably into phrases of 6+2+4+2 . Three stanzas evoke the sea, a phantom island, and the sea again, the voice entering with an independent melody to the opening accompaniment, though growing in animation, modulating widely and sharing the instrumental line and its striking dissonances against the harmony. The form is continuous, introduction A B development (including references to the introduction), with the postlude recalling the opening. In ‘Verzagen’ (‘Despair’) Op. 72 No. 4, the piano again begins with a strikingly instrumental main theme and florid accompaniment in 3/4 which could almost serve as a solo composition, over which the voice enters independently, with a simpler, contrasted line; it takes on an instrumental idiom in verse 3, shadowing and elaborating the piano to depict the text in which the poet compares his fears and woes to the waves dashing on the beach, unconsoled by the fact that they disappear in spray and that the clouds come and blow away. In contrast to the other settings the music of stanza 1 is marked for repeat in stanza 2. In other songs, the piano theme and texture dominate, or play an equal role with the voice: in ‘Abenddämmerung’ Op. 49 No. 5, the piano creates a shimmering atmosphere of twilight; in ‘Es schauen die Blumen’ Op. 96 No. 3, the piano evokes the metaphor of blooming flowers and rushing streams; in ‘Botschaft’ Op. 47 No. 1, the dancing piano introduction realises the breezes carrying messages of love.

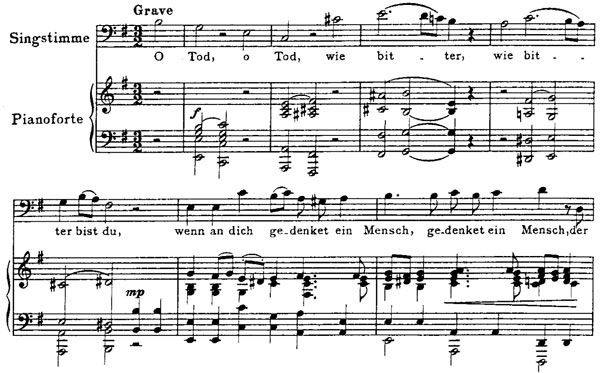

There are no comparable models for songs of dramatic character. Brahms wrote no opera, and there are few examples of the kind of dramatic recitative that seems to lie in the background of his many declamatory and dramatic songs. Only in the opening solo passage of the dramatic cantata Rinaldo is there any obvious precedent, and this is of an old-fashioned type from opera or oratorio as used in early Wagner and Mendelssohn. Brahms’s declamatory idiom soon took on a more lyrical form in the Op. 32 and Op. 33 songs, partly under the influence of the singing of Julius Stockhausen: a new lyrical-declamatory arioso style which adapted to the need to merge formal sections. Within this idiom he was to couch numerous expressive types. The idiom comes to an early flowering in the Requiem with its two baritone movements requiring the intonation of biblical prose rather than poetry, though he equalises the syllabic inequality through melodic means, involving repetition (‘Herr, lehre doch mich’ in movement 3;‘Siehe, ich sage euch ein Geheimnis . . .’ in movement 6). If there is a ‘goal’ to his dramatic style in the Lied , it is in the other biblical settings for solo voice, the Vier ernste Gesänge (‘Four Serious Songs’) Op. 121. In Op. 121 No. 3, ‘O Tod, wie bitter’ (Example 9.8 ), there is an obvious quality of recitative, where the stark words are given focus through repetition and shifted accentual position; but there is also a clear contrast to the more lyrical response ‘wenn an dich gedenket ein Mensch’ in a much more arioso style. After the opening has recurred, the consequent is transformed into an even more intense lyricism in the major key: ‘O Tod, wie wohl tust du’, and finally, ecstatically (in 3/2 metre),‘wie wohl, wie wohl bist du’.

Example 9.8 ‘O Tod, wie bitter bist du’ Op. 121 No. 3

(a) bars 1–7

(b) bars 18–25, transformation of theme into major

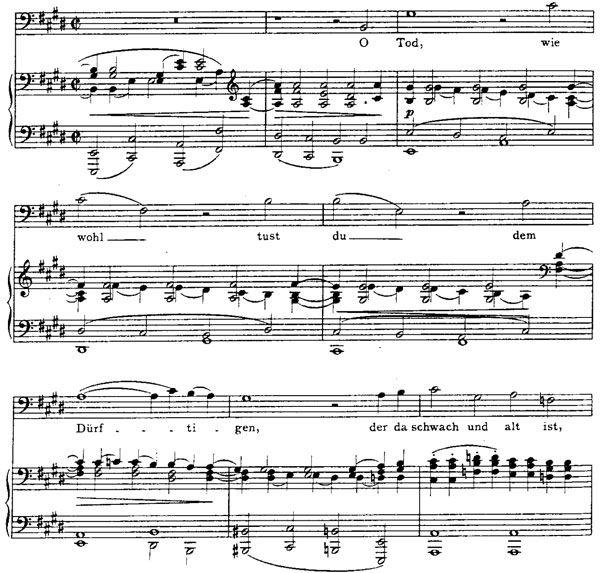

The subtle but distinct recitative–arioso relation in Op. 121 No. 3 finds a clear forebear in the late song ‘Auf dem Kirchhofe’ (‘In the Churchyard’) Op. 105 No. 4, in which the poet describes the wind-lashed cemetery, the graves almost covered over, the names marked ‘departed’ (‘gewesen’) – but then the revelation of the word ‘healed’ (‘genesen’) on these tombs with the clearing skies. Here the declamatory opening over pedal-based arpeggios in the piano yields to a clear quasi-recitative style with short uneven phases building to a repetition of the opening (Example 9.9a ). With the transformation of the text, the music is also transformed, into the clear major mode and the timeless shape of a chorale phrase (acknowledged by Brahms to have been prompted by the chorale ‘O Haupt von Blut und Wunden’), worked into a new melody to conclude the song (Example 9.9b ). 18

Example 9.9 ‘Auf dem Kirchhofe’ Op. 105 No.4

(a) bars 1–17

(b) bars 27–37, closing ‘chorale’

A possible model, or at least a forerunner, for this pattern, is the Alto Rhapsody , where Goethe’s imagery of wild thickets on all sides as a metaphor for the lack of direction of the misanthropic subject of the poem is followed by a lyric arioso passage for the one ‘for whom balm has become poison’), and eventually a chorale-type passage for chorus to the words ‘Is there in your Psalter, father of love, one word to refresh him?’ The form is essentially recitative, arioso and chorus, and its opening two sections could certainly be part of a staged dramatic work. The distinctive character of the opening, with its active bass figure seeming to determine the movement of the rapidly shifting harmony, finds another successor in Brahms’s later song ‘Steig auf, geliebter Schatten’ Op. 94 No. 2 to a text by Friedrich Halm. Here the imagery is again comparable: ‘Arise, Beloved Shadow, in dead of night appear’, though here the declamatory opening is part of a more continuous totality before it returns to complete the song.

That the recitative–arioso distinction was conscious in Brahms’s songs can be inferred from the presence of the term ‘recit.’ in the early song ‘An eine Aeolsharfe’ Op. 19 No. 5, written before Op. 32. This is the only song in which this indication appears, and it indicates the character of the passage as well as how it should be sung. The text uses the imagery of the Aeolian harp, or wall harp (whose strings vibrate freely with the wind), as the image of the recipient of messages from nature, here from the dead lover who has just been buried on the hillside with flowers. Cast in three stanzas, the text recalls the mystery of the ancient harp and its ballad of mourning: the winds bring the scent of springtime, and suddenly the wind quickens and the flowers are strewn at the lover’s feet. The contrast between description and invocation in verse 1 is reflected in the distinction between the ‘recit’ bars to describe the harp, and the lyrical response over repeated ‘harp chords’ in the piano to convey the desire for the message. The pattern is repeated for stanza 3 of the three-stanza structure.

One might well see Op. 19 No. 5 as prefiguring such a quiet, reflective idiom as that of ‘Herbstgefühl’ Op. 48 No. 7, in which the closing autumn is taken as a metaphor for resignation; ‘why play like the wind at leaf and stem . . . only be at peace’. Verse 1 is tentative, with the piano interpolating bars to give a story-telling quality, bleak and unresolved, built on the dominant of the key: it acts as a preparation for the outburst of verse 2 to a new idea, ‘thus a cold, night-dark day sends shivers through my life’, a dramatic contrast before the return of the opening material, which only at the end is resolved.

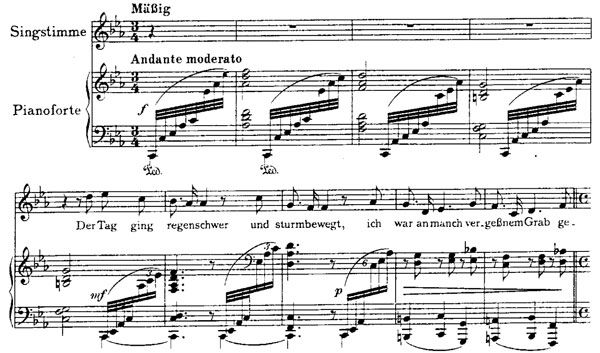

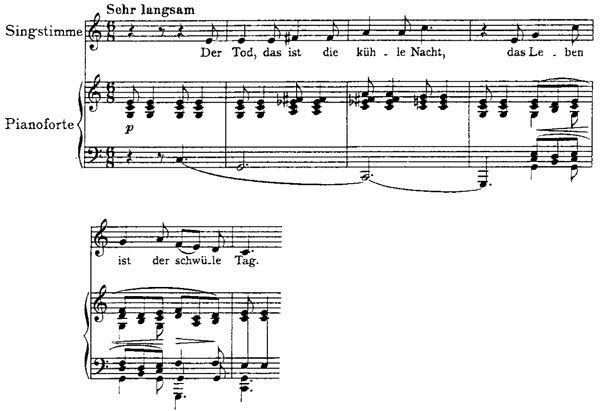

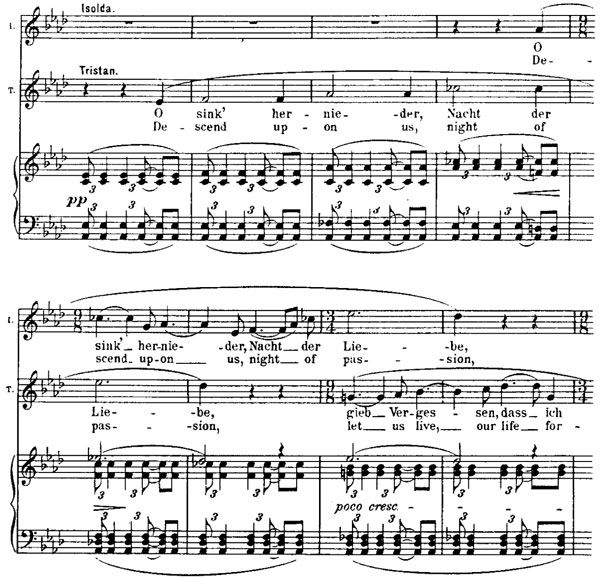

The idiom of the Heine setting ‘Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht’ Op. 96 No. 1 is strikingly Wagnerian. Its opening phrase (Example 9.10a ) is almost identical to that of ‘O sink’ hernieder, Nacht der Liebe’ in Act II of Tristan (Example 9.10b ) and uses the same accompanimental rhythm of syncopated repeated chords and chromatic dissonance in the voice, which almost floats above it in a slowly lyrical declamation of the utmost concentration. Here again there is a skeletal recitative–arioso distinction between opening and continuation in both cases. But Brahms’s single strophic poem imposes a structure, the first half continuing in a fragmented arioso , the second transforming the opening into a more expansive and periodic melody with a regular accompaniment figure and a touching final vocal cadence. The similarity arises from the analogous text, with its quintessential Wagnerian themes of night, death and love; it must be a homage on Brahms’s part to a composer he greatly admired, whose idiom has been adapted here to the needs of periodic song. Brahms’s text (by Heine) contrasts the coolness and clarity of night with the sultry day, which saps energy, in the opening recitative-like passage. The poet hovers between contemplating the peace of sleep and death and suffering the exhaustion of life. The nightingale sings of love as the ‘aria’ unfolds, but its ecstatic vision is soon quelled in the setting: the poet hears it only as if ‘in a far-off dream’, touchingly suggested by the refrain of this phrase before the hushed conclusion.

(a) ‘Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht’ Op. 96 No. 1, bars 1–6

(b) Wagner; ‘O sink’ hernieder, Nacht der Liebe’, Tristan und Isolde , Act 2 duet, opening

The setting of Brentano’s ‘O kühler Wald’ Op. 72 No. 3 also inhabits this idiom, with slow repeated chords and arpeggio bass against the same rising tone in the melody (Example 9.11 ). But here the harmony adjusts to the dissonance, and Brahms adapts the idiom to produce a rounded melody in two complementary parts, the second with an extended cadence, the whole varied for the second stanza; however, he modifies this form even further by commencing the second verse with a new phrase in a slower rhythm – to reflect the words ‘Im Herzen tief ’ – before continuing with the original material, more suited to the animated text ‘da rauscht der Wald’, which here requires a repetition of the second line to accommodate the repeating melody; the verse concludes with an even more extended cadence. The text portrays the murmuring of the cool forest which sends the lover’s messages; he asks if its echo understands his song; the murmuring mirrors his feelings and when the echo falls asleep in sorrow the song floats away. The setting creates a striking effect at its final cadence: not only are the last words ‘sind verweht’ repeated to a chromatically rising melodic line that mirrors the text, but the metre is changed from the prevailing triple to duple and the accompaniment to offbeat chords – further to suspend the sense of time – before the opening pattern of the accompaniment, again displaced rhythmically, rounds off the whole.

Example 9.11 ‘O kühler Wald’ Op. 72 No. 3, bars 1–13

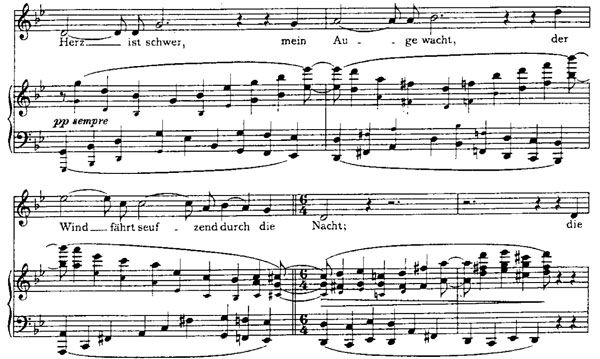

In conclusion, a particularly striking example of the synthesis of some of these basic types can be identified in the setting of Geibel’s ‘Mein Herz ist schwer’ (‘My heart is heavy’) Op. 94 No. 3 (Example 9.12 ). The idiom is not unlike that of ‘Alte Liebe’: it is set in the same original key, G minor, in the same alto range and with the same compound metre and pervasive rhythm (though it alternates its basic 9/8 metre with 6/8): its opening motive suggests that both are variants of the same idea. But the melody never develops as freely as that in ‘Alte Liebe’ because of the power of its accompaniment, a stark contrary-motion pattern in octaves which holds the melody in a declamatory brace dramatising the text ‘my heart is heavy, my eyes awake, the wind rides sighing through the night’. This quality continues into the second stanza, first with a simple repeated speech rhythm underpinned with syncopated piano chords; then the lyrical potential comes to the fore as the melody modulates widely: but it never loses the declamatory, constrained regular phrasing that prevents it from becoming a purely lyric or instrumental song akin to ‘Alte Liebe’. Even in a genre where synthesis is so often to be observed, this example stands out and again illuminates how the principles of variation and adaptation of style and structure to new contexts permeates Brahms’s music at every level: and how deep this traditional sense of craft, of the re-use of material, lies even within music as highly charged in expressive content as many of Brahms’s more elaborate and dramatic solo songs.

Example 9.12 ‘Mein Herz ist schwer’ Op. 94 No. 3, bars 1–15