risk, probably related to oestradiol levels, but shift to anaerobic predominance aided by progesterone injection.

risk, probably related to oestradiol levels, but shift to anaerobic predominance aided by progesterone injection.First described as ‘non-specific vaginitis’ in 1955 by Gardner and Dukes, with the term ‘bacterial vaginosis’ (BV) formally introduced in 1984.

Characterized by bacteriological imbalance of vaginal flora with the overgrowth of characteristic commensal bacteria replacing normally predominant Lactobacillus spp. and producing an altered vaginal discharge. Most common cause of abnormal discharge in women of childbearing age. Prevalence is probably around 5–10%, but may be as high as 50% in ♀ from some ethnic groups.

Vaginal hydrogen peroxide, H2O2-producing lactobacilli, ~60% of vaginal lactobacilli strains (especially Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus jensenii), appear to be protective as the prevalence of BV is only 4% compared with 32% in those with non-H2O2-producing organisms.

Developing BV is now recognized to involve the presence of a dense, structured, and polymicrobial biofilm. Biofilms are communities of microorganisms attached to a surface and encased in a polymeric matrix of polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids. In the case of BV, clusters of Gardnerella vaginalis produce the matrix and other bacteria then attach. The biofilm is also strongly adherent to the vaginal epithelium.

Due to the fact that bacteria within biofilms are not effectively eliminated by the immune system or fully destroyed by antibiotics; biofilm-related infections tend to persist and, not surprisingly, BV tends to have a high rate of relapse and recurrence.

The G. vaginalis biofilm in vitro displays high resistance to the protective mechanisms of normal vaginal microflora (H2O2 and lactic acid produced by lactobacilli), as well as an increased tolerance to antibiotics.

• G. vaginalis: facultative anaerobic small Gram –ve bacillus (often stains Gram +ve). Found in high concentrations (>×100 normal) in up to 95% of BV, but can be isolated in up to 58% of those with normal discharge. Vaginal carriage is associated with oral sex and hand-to-genital non-penetrative contact in ♀ who have never had penetrative vaginal sex.

• Anaerobic bacteria in high concentrations:

• Mobiluncus spp.: sickle-shaped rods displaying vigorous motility, including corkscrew motion, in vaginal wet mounts. Cultured in 14–96% ♀ with BV (<6% without) and seen on microscopy in up to 77%. Mobiluncus mulieris—long, Gram –ve. Mobiluncus curtisii—short, Gram variable, but usually stain positive.

• Prevotella spp. (e.g. P. bivia).

• Peptostreptococci (e.g. Streptococcus intermedius).

• Aerobic bacteria: e.g. streptococci, coliforms.

• Mycoplasma hominis: found in 24–75% ♀ with BV (13–22% without BV).

• More recently described bacteria:

• Atopobium vaginae—a metronidazole-resistant Gram +ve anaerobe frequently demonstrated in BV and may be responsible for metronidazole treatment failure.

• Leptotrichia/Sneathia, Eggerthella-like bacterium, Megasphaera spp.—three novel bacteria (BV-associated bacteria 1–3) in the order Clostridiales.

• Hormonal contraception: combined oestrogen/progesterone associated with a  risk, probably related to oestradiol levels, but shift to anaerobic predominance aided by progesterone injection.

risk, probably related to oestradiol levels, but shift to anaerobic predominance aided by progesterone injection.

• IUD: variable data, but possibly  risk.

risk.

• Vaginal douching: although only apparently associated with BV if flora already imbalanced.

• Diet: BV has been shown to be associated with  consumption of fat and severe vaginosis is associated with both saturated and mono-unsaturated fat. Increased intakes of folate, vitamin E, and calcium reduce the risk of severe vaginosis.

consumption of fat and severe vaginosis is associated with both saturated and mono-unsaturated fat. Increased intakes of folate, vitamin E, and calcium reduce the risk of severe vaginosis.

• Cigarette smoking:  risk of BV possibly due to anti-oestrogenic effect.

risk of BV possibly due to anti-oestrogenic effect.

• There is debate around whether purely an imbalance in vaginal flora or initiated as an STI. The following features suggest a sexual link:

• Lower mean age of coitarche.

• New sexual partner within previous 30 days, multiple sexual partners, unprotected heterosexual intercourse with associated anal sex.

• Associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.

• BV discharge (but not G. vaginalis in pure culture) inoculated into healthy vagina can induce BV in recipient

• Women who have sex with women—2.5-fold  rate compared with heterosexual ♀. Prevalence up to 25–52% with 20-fold

rate compared with heterosexual ♀. Prevalence up to 25–52% with 20-fold  if ♀ partner has BV. Apparent association with recent partner change, multiple concurrent partners, and receiving oral sex, but no other practices (including the shared use of dildos and anal penetration with fingers.)

if ♀ partner has BV. Apparent association with recent partner change, multiple concurrent partners, and receiving oral sex, but no other practices (including the shared use of dildos and anal penetration with fingers.)

• Against sexual transmission;

• Comparative study—BV found in similar proportion of virginal and sexually active adolescents (12% and 15%, respectively).

• Although G. vaginalis is isolated from the urethra in up to 80% of ♂ partners of ♀ with BV, their concurrent treatment does not  ♀ recurrence rate.

♀ recurrence rate.

• There is conflicting information regarding the circumcision status of ♂ partners.

• Vaginal discharge: symptom in 49% (20% without BV), sign in 69% (3% without BV):

• volume—usually moderate (varies from scanty to profuse)

• colour— grey > white > yellow

• nature—homogeneous vaginal discharge adhering to vaginal walls as a thin film). Frothy in 27–80% (1–18% normal ♀).

• Malodorous: fishy ammoniacal smell spontaneously reported in 20–49%, but probably higher (smell also reported in 20% without BV). Smell enhanced when vaginal pH  (e.g. during menstruation and following contact with alkaline prostatic fluid after intercourse), releasing volatile amines.

(e.g. during menstruation and following contact with alkaline prostatic fluid after intercourse), releasing volatile amines.

• Mild irritation: a non-inflammatory process so soreness and itching absent in most cases.

• N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis: 3.8-fold risk of N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis in ♀ with symptomatic BV.

• Cervicitis (with risk factors distinct from gonococcal and chlamydial infections), may be related to absence of H2O2-producing lactobacilli.

• Non-specific urethritis (NSU) in ♂ partner.

• Trichomoniasis: bacterial overgrowth as BV, but purulent discharge.

• HSV-2 infection and viral shedding.

• CMV infection and replication.

• Persistence (11–29%) and recurrence (72% by 7 months). Thought to be due to the inability of antibiotics to fully eradicate BV vaginal biofilm-associated bacteria.

• Post-hysterectomy vaginal cuff cellulitis.

• Possibly contributes to spontaneous PID and STI (including HIV) acquisition.

• In pregnancy: increased bacterial production of cytokines and prostaglandins and amniotic fluid/chorio-amniotic infection leading to:

• preterm birth (relative risk 1.5–2.3); history of previous premature delivery  risk of further preterm birth 7-fold with BV.

risk of further preterm birth 7-fold with BV.

• 2nd trimester miscarriage (up to 3–6-fold risk)

• endometritis (pre/post-delivery, including caesarean section).

It is a condition caused by the overgrowth of normal vaginal bacteria causing an imbalance and an altered vaginal discharge.

It is not thought to be sexually transmitted, and so partners of ♀ with BV are not routinely treated.

Thrush (candidiasis) is caused by a yeast, usually Candida albicans (90%). BV is due to an imbalance of normal vaginal flora, with a loss or reduction in lactobacilli and an overgrowth of largely anaerobic bacteria, especially

Thrush usually causes a thick white vaginal discharge, itching, and soreness. BV is usually associated with a thin white/grey discharge and an offensive fishy smell.

Both thrush and BV have the potential to recur.

No. Thrush is treated with topical azoles (pessaries/creams) or oral azoles. BV is treated with metronidazole or clindamycin either topically or orally.

It is not sexually transmitted. ♂ may occasionally develop balanitis with bacteria similar to those found with BV, but it does not appear to be related to intercourse with a partner who has BV. However, the increased incidence of BV in lesbian couples suggests a sexual link.

No. Treating an asymptomatic partner does not make any difference to recurrence rate.

Overall cure rate is 95%. Recurrence rate is about 15–30% with the majority recurring within 7 months of treatment.

♀ who suffer from recurrent BV can be treated with episodic, anticipatory, or cyclical metronidazole or clindamycin. As BV is associated with a high vaginal pH, it is advisable to try to keep it low to prevent recurrences. This can be done by decreasing menstruation, e.g. with medroxyprogesterone acetate or using acidic vaginal gels. If a ♀ has an IUD and suffers from recurrent or persistent BV, it may be advisable to remove the IUD and try another method of contraception.

BV is associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery. Therefore, it is recommended that in ♀ with a history of a preterm delivery screening for BV is considered during pregnancy and treated if positive. It is not recommended that all pregnant ♀ are screened for BV. However, if a pregnant ♀ is found to have BV during routine testing (e.g. for a symptomatic discharge), she should be treated. Metronidazole is safe in pregnancy in all trimesters, although large doses are best avoided.

Detection of G. vaginalis by culture cannot be used to diagnose BV as it can be isolated in >50% of ♀ with normal vaginal flora.

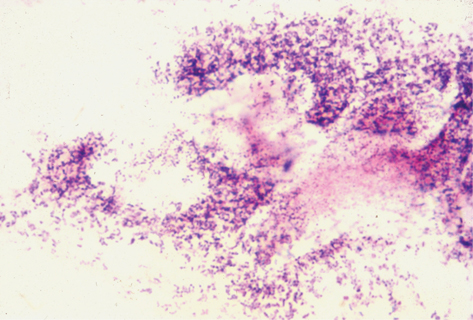

Simple, fast, and accurate way to diagnose BV. Typical appearance is substantial reduction or absence of lactobacilli (Gram-positive rods) replaced by small Gram-variable bacilli (G. vaginalis) adhering to shed epithelial (‘clue’) cells without polymorphs (Plate 2). Other small Gram-negative bacilli (e.g. Bacteroides spp.), Gram-positive cocci (e.g. peptostreptococci), Gram-variable sickle-shaped rods (Mobiluncus spp.) may be found. The last of these are seen more easily as motile organisms on a wet mount which may also show long thin pointed rods (fusiform bacilli).

Plate 2 Gram stain BV (15).

Simple qualitative method grading smears as follows:

• grade 0: epithelial cells/no bacteria

• grade I (normal): lactobacilli only

• grade II (intermediate): reduced lactobacilli/mixed bacteria, not found in BV as diagnosed by Amsel’s criteria

• grade III (consistent with BV as diagnosed by Amsel’s criteria), mixed bacteria with few or absent lactobacilli

• grade IV: epithelial cells covered with Gram +ve cocci only.

Although sensitive, this method is too complex and time-consuming for routine clinical use. It is based on the quantitative scoring of Lactobacillus, G. vaginalis, Bacteroides morphotypes, and Mobiluncus spp. on a Gram-stained vaginal smear. High scores (>6) equate to BV, medium scores (4–6) intermediate, and 0–3 normal.

Three of four criteria to be fulfilled:

• Positive amine (‘sniff’ or ‘whiff’) test: drop of 10% potassium hydroxide on vaginal fluid releases ‘fishy’ smelling amines (avoid semen, which may give false-positive result). No longer recommended for safety reasons.

• pH >4.5 (avoiding cervical mucus (pH 7.0), blood, and seminal fluid).

• Vaginal ‘clue’ cells on wet-mount microscopy.

• Sensitivities and specificities of the separate components are shown in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1 Sensitivity and specificity of Amsel criteria

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

| Amsel criteria | ||

| Atypical discharge | 52–69 | 78–97 |

| pH >4.5* | 97 | 53 |

| Amine test* | 43–80 | 99 |

| Clue cells | 80–90 | 94 |

* Provided that sample is not contaminated with blood or seminal fluid.

• Home tests are available in some areas. These rely on a combination of vaginal pH and symptom scoring to enable women to differentiate between thrush, BV, or TV, as the potential cause of their symptoms.

• POCT (chromogenic enzyme activity test): detecting elevated vaginal sialidase (enzyme produced by G. vaginalis and other BV associated bacteria) and reporting sensitivities of 93% and specificities of 98% when compared with Gram stain.

Offer an STI screen as standard. Variations in vaginal bacterial flora are common and BV-type features are often transient and self-limiting. Treatment is recommended for those with symptoms, those with clear signs of BV (who may report improvement after treatment), and those undergoing certain surgical procedures, but otherwise not for asymptomatic BV or G. vaginalis colonization. The use of a soap substitute can be advocated.

• oral—400 mg bd for 5–7 days (or 2 g as a single-dose, but higher failure rates have been reported)

• intravaginal—0.75% gel once daily (usually at night) for 5 days

• intravaginal—2% cream od for 7 days (can weaken condoms).

• Tinidazole (oral): 1 g daily for 5 days, 2 g daily for 2 days, or 2 g as a single dose.

Studies show that 7 days of oral metronidazole are as effective as 5 days of vaginal gel (symptomatic and microbiological cure rates of about 80% and 70%, respectively, at 1 month) and similar to clindamycin cream.

Alcohol produces a disulfiram-like reaction in some people when taken with metronidazole, and possibly tinidazole, and should be avoided. No data are available on intravaginal preparations, but alcohol ingestion is not recommended. Both oral and topical clindamycin have been associated with pseudomembranous colitis.

Alcohol produces a disulfiram-like reaction in some people when taken with metronidazole, and possibly tinidazole, and should be avoided. No data are available on intravaginal preparations, but alcohol ingestion is not recommended. Both oral and topical clindamycin have been associated with pseudomembranous colitis.

No evidence of  relapse rate if male partners are treated epidemiologically, but male condom may reduce the BV recurrence rate up to 5-fold. No data available on the value of treating female partners concurrently.

relapse rate if male partners are treated epidemiologically, but male condom may reduce the BV recurrence rate up to 5-fold. No data available on the value of treating female partners concurrently.

Caution is advised in the use of metronidazole during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and high-dose regimens should be avoided. However, meta-analyses have shown no evidence linking birth defects to the use of metronidazole in early pregnancy. Antibiotic treatment can eradicate BV in pregnancy and it is advised for those with symptoms.

Data has been conflicting on whether screening and treating is beneficial. Evidence to support screening and treating all pregnant ♀ with asymptomatic BV in order to prevent preterm birth and its consequences is lacking even for women with recurrent or persistent BV. There is some suggestion that treatment before 20 weeks’ gestation may  risk of preterm birth. It may be therefore that consideration of other risk factors for preterm birth be taken into account when deciding on screening and treating individual women.

risk of preterm birth. It may be therefore that consideration of other risk factors for preterm birth be taken into account when deciding on screening and treating individual women.

As both systemic metronidazole (alters the taste) and clindamycin enter the breast milk, intravaginal treatment should be considered.

Based on three independent studies, screening for and treating BV with metronidazole or clindamycin cream prior to TOP should be considered to  the incidence of subsequent endometritis and PID.

the incidence of subsequent endometritis and PID.

Eliminate possible factors that may influence the microbiological flora (e.g. douching, shampoos, spermicides, smoking). Lack of evidence, but consider the following;

• change treatment (metronidazole to clindamycin, or vice versa)

• consider removing IUD if in situ

• oral co-amoxiclav (amoxicillin 250mg + clavulanic acid 125mg) 375mg 3 times a day for 7 days, as possibility of resistance or metronidazole de-activation by other vaginal bacteria. May also be considered initially if metronidazole and clindamycin cannot be used.

• Recurrent: following initial treatment mildly abnormal microscopy or elevated pH may be found suggesting relapse, rather than a new episode. If relevant, consider stopping menstrual flow (contraception) to maintain low pH. Ten days of induction therapy with vaginal metronidazole followed by twice weekly gel for 16 weeks can establish clinical cure of 75% at 16 weeks and 50% at 28 weeks. Other strategies include episodic, anticipatory, pulse, suppressive (e.g. twice weekly for 4–6 months using metronidazole gel 0.75% or clindamycin cream), or cyclical (e.g. oral metronidazole 400 mg bd for 3 days at the start and end of menstruation) treatment regimens.

• Other approaches (with the aim of disrupting biofilm formation):

• probiotics—oral/vaginal lactobacillus replacement (limited data, but no conclusive evidence of benefit)

• agents lowering vaginal pH (e.g. lactic or acetic acid gel)—suggested in those with recurrent BV (used as maintenance treatment) or in situations that raise pH, such as seminal fluid or menstrual blood in the vagina (e.g. for 3 days post-menstruation).

Male partners of ♀ with BV are usually asymptomatic and unlikely to develop balanitis/balanoposthitis.

Prevalence of G. vaginalis in men is 5-fold higher in heterosexual men than MSM.

G. vaginalis can be found in 31% of those with a non-candidal balanoposthitis. Usually mild, but may be foul smelling in association with anaerobes, especially Bacteroides spp. (commonly B. melaninogenicus). Normally found in those with underlying phimosis and poor hygiene. An offensive sub-preputial discharge may occur with erosions and preputial oedema. Usually resolves with advice on hygiene and the use of saline lavage, although oral metronidazole is sometimes required. Clindamycin cream 2% bd or oral co-amoxiclav 375 mg 3× a day for 1 week may also be used.

• Acquisition and transmission of HIV is  with BV 2–5-fold.

with BV 2–5-fold.

• The acquisition of H2O2-producing lactobacilli significantly reduces HIV RNA in female genital secretions, while their loss  these levels compared with stable colonization.

these levels compared with stable colonization.

• The presence of BV has been shown to reduce the efficacy of tenofovir (TDF) containing vaginal PrEP, but further studies in relation to this are needed.

Further information