Plate 5 Dark-ground trichomonas vaginalis (16).

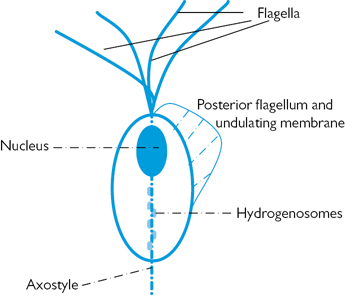

Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) was first described by Donné in 1836. A flagellated protozoan of the order Trichomonadida, which is parasitic to the human genitourinary tract (Fig. 16.1 and Plate 5). TV is usually oval and measures up to 15 µm in length in vivo (the size of a leucocyte). It is propelled by four anterior flagella arising from an anterior kinetosomal complex. An additional fifth flagellum is attached to an undulating membrane that extends halfway down the organism and an axostyle projects from the end of the body. Trichomonads lack mitochondria, but contain hydrogenosomes, large cytoplasmic granules involved in catabolism. It grows in a moist environment at 35–37°C and pH 4.9–7.5 (similar to bacterial vaginosis). Multiplication is by mitosis, occurring optimally every 8–12 hours.

Plate 5 Dark-ground trichomonas vaginalis (16).

Trichomonads infected by double-stranded RNA viruses have been identified, and are termed type II in contrast with virus-negative organisms designated type I. In a small comparative study type II isolates were found proportionately more commonly in ♀, especially older ♀.

Fig. 16.1 Trichomonas vaginalis.

Common worldwide, but steady decline in developed countries over the past 20 years. Reason is unclear, but may relate to standard cervical cytology screening, which can also detect TV. Almost exclusively sexually transmitted from infected genital secretions.

The parasite can be found in:

• ♀: vagina, cervix, urethra, bladder, and the ducts of Bartholin’s and Skene’s glands.

• ♂: anterior urethra, sub-preputial sac, glans penis, prostate, epididymis, and semen.

• Most commonly found in ♀ during the most sexually active years (16–35 years) and in those more sexually active (change in partner, intercourse twice weekly or more, 3 partners in past month).

• Recognized association with other STIs (e.g. gonorrhoea).

• High rate of re-infection unless ♂ partners are treated.

• Detection rates in ♂contacts of infected ♀:

• sex within previous 48 hours—70%

Detection rates in ♀ contacts of infected ♂: 67–100%. ♀ to ♀ sexual transmission well recognized; may relate to the shared use of sex toys.

Protozoa may survive up to 45 minutes on toilet seats and for several hours in moist clothes, although transmission is unlikely.

Neonatal vulvovaginitis arising from infection acquired at delivery may arise, but is rare (5% of those born to mothers with TV). Commonly asymptomatic and usually spontaneously clears in 3–6 weeks as maternal oestrogen level falls.

Generally, yes, although it has been suggested that transmission could occur through moist flannels that are shared.

Symptoms usually develop within a month of acquiring infection, although up to 50% of ♀ are diagnosed without symptoms.

Yes. ♂commonly carry T. vaginalis without any symptoms. Unless treated there is a high rate of re-infection.

Incubation period (before symptoms develop): 4–28 days.

• 10–50% asymptomatic (depending on criteria).

• Low abdominal pain (probably related to vaginitis): up to 12%.

• Vaginal malodour: ~50%, associated with concurrent anaerobic bacterial overgrowth.

• Altered vaginal discharge in up to 70%, frothy yellow in 10–30%.

• ‘Strawberry cervix’ (colpitis macularis): small punctate cervical haemorrhages with ulceration found in 2–5%.

• Isolated case reports of detection from fallopian tubes (in salpingitis) and peritoneal fluid.

• Independent association in pregnancy with premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth weight. Not proven to be causal.

• Although treatment of symptomatic ♀ is advocated, the risk of preterm birth is not  with metronidazole treatment. One study of asymptomatic ♀ treated with metronidazole was stopped as there was an association with

with metronidazole treatment. One study of asymptomatic ♀ treated with metronidazole was stopped as there was an association with  risk of preterm birth. Routine screening in pregnancy is not advised.

risk of preterm birth. Routine screening in pregnancy is not advised.

Association with cervical carcinoma reported, but uncontrolled for other genital pathogens (e.g. HPV); therefore, no proven causal relationship.

• Most common sign: small to moderate urethral discharge—NGU. Trichomonal infection may be the cause in up to 15% of cases in high-prevalence areas. May present with dysuria.

• Balanoposthitis: 4–11% (rarely with ulceration).

• Reports of prostatitis, epididymitis, cystitis, penile ulceration, and median raphe suppuration.

Test women presenting with vulvitis and/or vaginitis (swab from posterior fornix, self-taken vaginal swab, consider urine) and men who are either TV contacts or present with persistent urethritis (urethral specimen and/or urine).

Vaginal discharge examined as an isotonic saline suspension by phase contrast or dark ground microscopy. Slides must be read within 10 minutes as motility of the protozoa quickly declines and identification becomes harder. Readily recognizable motile protozoa propelled by flagella and undulating membrane are seen at ×400 magnification. (Fig. 16.1 and Plate 5). ♂ urethral discharge and sub-preputial material can be examined in a similar fashion. Alternatively, dried smears can be stained with acridine orange and viewed using fluorescent microscopy. This is more sensitive than wet preparations, but rarely used.

Compared with culture, the overall sensitivity of microscopy in ♀ is 40–80%, but in ♂ it is only ~30%, although the specificity is high.

Gram-stained vaginal smears typically show polymorphonuclear leucocytes, reduced or absent lactobacilli, and a mixed bacterial flora, as with BV. However, there is considerable variability.

PCR should now be the test of choice where resources allow. The sensitivity of culture compared with PCR is poor, ranging from 34% to 59%, although its specificity is high at ~100%. TV PCR tests have sensitivities of 88–97% and specificities of 98–99%.

As well as vaginal, urethral, and sub-preputial samples, a centrifuged deposit of first morning urine can also be tested by culture (especially useful for ♂). Ideally, specimens should be placed in culture medium (e.g. Feinberg–Whittington). Otherwise, forward in transport medium (e.g. Amies or Stuart) and inoculate in growth medium within 24 hours. Microscopy is then carried out in the laboratory daily for 5 days. Culture is under partial or complete anaerobic conditions.

Detect TV antigen. Have advantage over culture or PCR of giving a result within 15 minutes and have greater sensitivity (80–94%) than microscopy. Caution if using in a low prevalence population due to risk of false positives.

TV is sometimes reported on cervical cytology. Sensitivity varies (60–80% compared with culture), but specificity is reported as over 98% with liquid-based cytology. The gold standard would be to confirm positive cases by microscopy ± culture. If unconfirmed the sensitivity and specificity of the tests, together with history and examination findings should allow a clinical decision to be made.

• Sexual partners should be treated simultaneously, and sexual intercourse avoided until treatment has been completed.

• If ♂ contacts present with NGU, it is reasonable to treat initially as TV infection and review after treatment.

• Screening for other STIs for patients and their contacts is advised.

• Treatment should be systemic in view of the high rates of urethral and para-urethral gland involvement.

• Spontaneous resolution is estimated at around 20–25% in women.

The only effective agents are the 5-nitroimidazoles (overall cure rates ~95%). There are no reliable alternative antibiotics.

400–500 mg bd for 5–7 days or 2g in a single dose. If allergy reported consider metronidazole desensitization. Single dose has the advantage of  adherence but has lower cure rate (by 6–12%), especially if partner(s) not treated simultaneously.

adherence but has lower cure rate (by 6–12%), especially if partner(s) not treated simultaneously.  Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol while taking treatment and for 48 hours thereafter, because of a possible disulfiram-like (Antabuse®) reaction (similar reaction possible with tinidazole). Vaginal metronidazole cream is not advised as cure rates only ~20% probably because of poor absorption and failure to penetrate infected Bartholin’s and Skene’s glands, and urethra. Plasma levels achieved when administered rectally or vaginally are only 50% and 20%, respectively, of those of oral metronidazole (although this varies with the formulation). Body weight plays a role in drug excretion; therefore, some fixed-dose regimens may not be appropriate for all patients. Although caution is advised in the use of metronidazole during pregnancy the manufacturers only warn against high-dose regimens; should also be avoided during breastfeeding.

Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol while taking treatment and for 48 hours thereafter, because of a possible disulfiram-like (Antabuse®) reaction (similar reaction possible with tinidazole). Vaginal metronidazole cream is not advised as cure rates only ~20% probably because of poor absorption and failure to penetrate infected Bartholin’s and Skene’s glands, and urethra. Plasma levels achieved when administered rectally or vaginally are only 50% and 20%, respectively, of those of oral metronidazole (although this varies with the formulation). Body weight plays a role in drug excretion; therefore, some fixed-dose regimens may not be appropriate for all patients. Although caution is advised in the use of metronidazole during pregnancy the manufacturers only warn against high-dose regimens; should also be avoided during breastfeeding.

2 g in a single dose is an alternative. It is unknown whether there is cross-reactivity between metronidazole and tinidazole, therefore, it cannot be considered safe in cases of metronidazole allergy.

Tinidazole should be avoided in pregnancy.

Treatment failure is due to inadequate therapy (check adherence, vomiting), re-infection or resistance:

• Low plasma zinc may contribute to treatment failure (unusual): provide oral zinc supplement.

• 5-nitroimidazole deactivation by vaginal bacteria: no evidence to support this, but theoretically, aerobes and anaerobes, including β-haemolytic streptococci, could be implicated. Consider concurrent treatment with amoxicillin or erythromycin.

• Resistance: 5% of all clinical strains estimated to have at least some metronidazole resistance. Generally aerobic, but anaerobic resistance has also been reported. Resistance testing should be conducted in aerobic conditions, but is not readily available. Although metronidazole-resistant strains show  susceptibility to oral tinidazole, the minimal inhibitory concentration is likely to be significantly

susceptibility to oral tinidazole, the minimal inhibitory concentration is likely to be significantly  . Tinidazole has a longer half-life, good tissue penetration, and lower levels of resistance, and should, therefore, be considered in this scenario.

. Tinidazole has a longer half-life, good tissue penetration, and lower levels of resistance, and should, therefore, be considered in this scenario.

• 40% will respond to a repeat (7-day) course of standard therapy.

• If no response, then 70% of those remaining will respond if given a higher dose course (metronidazole or tinidazole 2 g daily for 5–7 days or metronidazole 800 mg tid for 7 days).

• If treatment failure follows and resistance testing is unavailable, very high dose tinidazole (1 g bd or tid or 2 g bd for 14 days) can be used. Consider the addition of intravaginal tinidazole 500 mg bd alongside this. 90–92% of those who failed the previous regimens respond to this.

• Intravaginal paromomycin or intravaginal furazolidone or acetarsol pessaries or nonoxynol-9 pessaries are all unlicensed preparations reported to have some success.

Consider if the patient remains symptomatic following treatment, or if symptoms recur.

Current partners and sexual contacts from the preceding 4 weeks should be offered a full STI screen, including a test for TV, but offered treatment irrespective of the result. If urethritis is present in this scenario, this should be treated as TV first line.

• TV may enhance HIV transmission (probably related to genital inflammation) Successful treatment of trichomonal urethritis in men  levels of HIV RNA.

levels of HIV RNA.

• There may be an increased risk of TV infection in those who have HIV.

• Single, high-dose metronidazole is possibly less effective in those with HIV. Consider a 7-day course.

Further information

https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1042/tv_2014-ijstda.pdf

https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1042/tv_2014-ijstda.pdf