in smokers (>5-fold).

in smokers (>5-fold).References to anogenital warts date back to Roman and Hellenic periods, with Celsus observing, in the 1st century ad, that anal warts resulted from sexual intercourse.

HPV is in the family of papilloma viruses with a double-stranded DNA structure. It infects the mucosa of the anogenital tract, upper respiratory tract, and surface of the skin. The virion is 55 nm in diameter. The capsid (envelope) comprising 72 capsomeres has an icosahedral symmetry. Hybrid capture II and PCR are highly sensitive in detecting HPV.

HPV is classified by the nucleotide sequence of the major capsid gene L1 into >100 types, which are identified by a number and are usually site specific (Table 23.1). Types frequently detected in anogenital squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) are described as oncogenic (‘high risk’) and the remainder as non-oncogenic (‘low risk’). ‘Low-risk’ types HPV6 and HPV11 account for ~90% of anogenital warts; ‘high-risk’ HPV is found in >95% of cervical squamous cell carcinomas. 80–85% of anal carcinomas, 50% of penile carcinomas, 40–70% vulval and vaginal carcinomas, and 70% of oropharyngeal carcinomas. HPV 16 is most commonly implicated in high grade neoplasias. Infection begins in the basal stem cells of the epithelium. Active viral replication occurs in the well-differentiated layers near the surface. Virions are then released from desquamating cells.

Table 23.1 HPV types in lesions

| Lesion | HPV types (more common types in bold) |

| Skin warts | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 10, 26, 28, 29, 41, 49, 57, 60, 63, 65 |

| Anogenital warts | 6, 11, 16, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 55, 61, 72, 73, 81 |

| Squamous intra-epithelial lesions* | 6, 11, 16, 18, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 52, 56, 57, 58, 59, 62, 64, 67, 68, 69, 70 |

| Anogenital squamous cell carcinoma | 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68 |

| Oral warts | 2, 6, 11, 16 (7, 13, 18, 32 in HIV +ve) |

| Laryngeal papilloma | 6, 11 |

| Head and neck carcinoma | 16, 18, 33, 57 |

* Cervical, vaginal, vulval, anal, or penile intra-epithelial neoplasia.

With the introduction from 2008 of national HPV vaccination for girls in the UK, the incidence rates of genital warts in ♀ and heterosexual ♂ aged 16–25 years has fallen steadily. However, genital warts remain one of the most common STIs and accounted for 16% of new diagnoses in GUM clinics in 2015. In MSM and unvaccinated heterosexuals genital tract HPV DNA is found in 10–40% of those aged 15–49 years. It is estimated that the majority of the sexually active population will have HPV infection at some time. However, <10% have clinically apparent lesions. The peak age of prevalence is 20–24 years in ♂ and 16–24 years in ♀. The infection rate  in smokers (>5-fold).

in smokers (>5-fold).

The incubation period of genital warts is usually 3–8 months, but can be much longer. In the immunocompetent, 70% of warts regress within 1 year and 90% within 2 years. Immune response to E6 antigen leads to clearance, but E7 results in persistent or relapsing infection, which in high risk types may lead to development of squamous cell carcinoma. Following visible regression HPV may still be present, but in ~95% can no longer be detected 2 years after infection.

Transmission is through contact with apparent or subclinical epithelial lesions and/or genital fluids containing infective virus, usually during sexual intercourse (including non-penetrative contact). Resultant micro-abrasions enable viral inoculation into the basal layers of the epithelium. Occasional reports of anogenital types at other sites (e.g. fingers) and non-anogenital types on anogenital skin suggest digital–genital transmission (including auto-inoculation). This may explain the absence of a history of genital–genital/anal or oro-genital–anal sexual contact reported in ~1% of ♀ with anogenital warts (no data available for ♂). The finding of oral, laryngeal, conjunctival, and nasal lesions in those with anogenital warts (~5%), with the same HPV type, suggests oro-genital transmission.

Mother-to-child transmission may occur during vaginal delivery, with a 10–70% rate of neonatal infection, and has also been reported following Caesarean section. In prepubertal children digital warts may be transmitted to anogenital regions, up to 20% of which may be due to skin types.

Usually little physical discomfort, but disfiguring lesions may lead to psychological distress. Peri-anal or large growths may cause irritation and soreness. Urethral, anal, and cervical warts may cause bleeding, and urethral warts may distort the urinary stream.

Plate 15 Anogenital warts (23).

Warts (usually multiple) appear most commonly at sites likely to be traumatized during sexual intercourse with HPV detectable in apparently normal surrounding skin. Peri-anal and anal warts (almost always below the pectinate line) may occur in both ♂ and ♀, more commonly, but not only with receptive anal sex. Warts may be found on the cervix, and in the vagina, anal canal, urethral meatus, with rare involvement of urethra and bladder (Table 23.2)

Table 23.2 Relative frequency (reported range) of location of genital warts

| % of cases (range) | % of cases (range) | ||

| Prepuce | 65 (49–80) | Posterior introitus | 73 (77–94) |

| Frenulum, corona and glans | 46 (22–70) | Labia, clitoris | 32 |

| Urethral meatus | 34 (24–45) | Cervix | 34 (6–64) |

| Penile shaft | 27 (16–55) | Vagina | 42 (32–52) |

| Scrotum | 23 (2–25) | Urethra | 8 |

| Peri-anal area | 8 (3–15) | Perianal area | 18 (13–85) |

| Perineum | 23 |

Lesions are either pedunculated or sessile and sometimes pigmented. They may be:

• Condylomata acuminata: soft/non-keratinized, ‘cauliflower-like’ in appearance, found on mucosae/warm moist non-hairy skin.

• Keratinized: resembling skin warts, usually on dry anogenital skin.

• Smooth papules on dry skin (e.g. penile shaft).

Subclinical infection may be detected as aceto-white patches with 5% acetic acid, better visualized through a colposcope ( low specificity). Atypical balanoposthitis/vulvitis may be associated with HPV

low specificity). Atypical balanoposthitis/vulvitis may be associated with HPV  .

.

Usually associated with HPV6 and HPV11. Resembles a very large wart, but invades the dermis and underlying tissue (e.g. corpus cavernosum). Starts as a keratotic papule and grows into a large cauliflower-like lesion. Most commonly located on the glans penis, but may occur anywhere on the penis, scrotum, vulva, vagina, rectum, and bladder. Does not metastasize, but malignant transformation (verrucous carcinoma) develops in up to 50%. Diagnosed histologically. Liable to recur if not completely excised.

• Usually on clinical appearance.

• speculum for vaginal/cervical warts

• proctoscopy for anal warts if peri-anal lesions present

• urethral meatoscopy (with an otoscope) if meatal warts.

• Biopsy under local anaesthetic if in doubt, or lesion atypical, or pigmented. This may be aided by the use of a colposcope.

• Routine DNA detection is unnecessary and is not cost effective.

• Differential diagnoses are outlined in Table 23.3.

Table 23.3 Differential diagnosis of external anogenital warts

| Achrocordon (skin tag) | Molluscum contagiosum |

| Epidermal/melanocytic naevi | Condylomata lata (secondary syphilis) |

| Sebaceous glands | Seborrhoeic keratosis |

| Penile pearly papules | Dermatofibroma |

| Vulval papillae | Angiokeratoma |

| Ectopic sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots) | Epidermal cyst |

| Prominent hair follicles | Lichen planus |

| Nabothian follicles (cervix) | Psoriasis |

| Penile/anal intra-epithelial neoplasia | |

| Giant condyloma of Buschke and Lowenstein | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Basal cell carcinoma |

Warts may rapidly enlarge with pronounced vascularity during pregnancy (probably as a result of altered immunocompetence or  oestrogen/progesterone) and regress in the puerperium, often with complete resolution. Warts do not usually obstruct vaginal delivery.

oestrogen/progesterone) and regress in the puerperium, often with complete resolution. Warts do not usually obstruct vaginal delivery.

Neonatal infection commonly clears within 6 weeks. Persistence is usually subclinical, but may lead to recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, or ano- or extra-genital warts. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis incidence is 0.25% in children (3 months–5 years of age) born to mothers with warts. Mainly caused by HPV6 and HPV11. Usually located on the vocal cords and epiglottis (laryngeal papillomas), rarely on the entire larynx, tracheobronchial tree, or even the lungs.

Perinatal infection is the usual cause of anogenital warts in children up to 3 years of age. However, sexual abuse and non-sexual transmission should be considered in older children.

The aim of treatment is essentially cosmetic or for symptomatic relief. Systematic reviews of RCTs of all treatment modalities show a lack of high quality comparative studies. No method can be recommended as superior to another. Therapy aims to reduce visible warts, but does not necessarily effect eradication of HPV or reduce infectivity. Diagnosis of subclinical infection is of no practical benefit. In immunocompetent adults 40% warts resolve spontaneously within 4 months Treatment options, therefore, include no treatment at all.

Genital warts are usually sexually transmitted by direct skin-to-skin contact. It is thought that ~90% of people who are infected with HPV have no visible warts. After infection, it takes a mean of 3 months for warts to develop, but may extend to months or years.

Warts left untreated may disappear on their own (usually within 18 months), but they can also grow and spread, becoming unsightly and more difficult to treat.

When warts are treated they should clear, but HPV may persist, depending on the host’s immunological response. Therefore, the patient should be warned that they may recur. Recurrences are more likely within 3 months of treatment. HPV usually clears within 24 months, although this may be longer, especially if the patient is immunocompromised.

Someone infected with HPV is infectious until it clears. The level of infection is probably greater when warts are present as viral shedding is likely to be greater.

It is recommended that if visible warts are present condoms should be used during sex—they do not completely prevent transmission of HPV, but do reduce the risk. Friction associated with coitus may spread warts. However, it is likely that the regular partner of someone who has warts will also be infected with the wart virus, whether they have visible warts or not.

There are many strains of HPV, but those causing genital warts are different from the types associated with cervical cancer. It is recommended that a ♀ attends for routine smear tests that will detect abnormalities associated with the HPV strains that may be related to cervical cancer. ♀ with warts do not need extra smears.

Only if there are concerns about possible warts or other STIs.

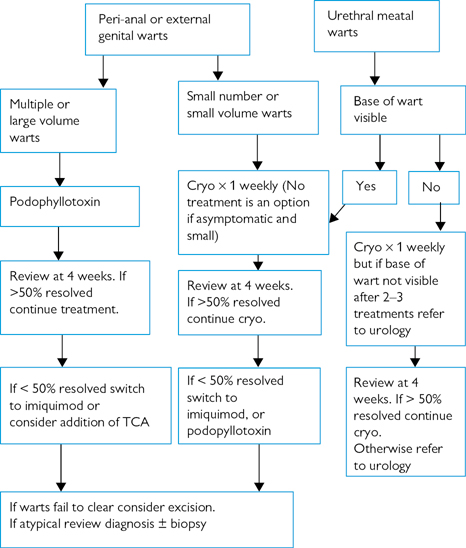

The use of a clinical algorithm to direct treatment choice improves treatment outcome (Figs 23.1 and 23.2).

Fig 23.1 Treatment algorithm for genital warts in women

Treatment choice should encompass patient preference.

▶ Risk of scarring and pigment changes should be discussed before treatment.

Serial documentation of the number, size, appearance, and distribution of warts in genital maps gives a visual record of treatment response. If the wart area is >4 cm2 treatment under direct supervision of clinical staff is recommended.

Consistent use of condoms reduces the acquisition of HPV infection and genital warts by 30–60%, and may also reduce the time to resolution of visible warts, when both partners are infected. Smoking cessation should be encouraged.

Psychological distress may require referral for counselling. The possibility of a long incubation period should be discussed, especially if there are concerns about infidelity.

Scissor excision and electrosurgery have the best chance of complete clearance at first visit (approaching 100%) Clearance rates for other modalities vary and are roughly equivalent. Most warts respond to treatment within 3 months Recurrence following clearance with all therapies, particularly in the first 3 months is common. All methods may cause local skin inflammation, irritation, ulceration, and pain.

• Podophyllotoxin: the active lignan ingredient of podophyllin resin and an antimitotic agent cause local tissue necrosis. Available as 0.5% solution or 0.15% cream. Should be applied bd for 3 consecutive days, repeated at weekly intervals for a total of up to 4–5 three-day treatments. Cream may be easier to apply. Repeat cycles, although not licensed, may be considered if warts are responding.

• Imiquimod 5% cream: stimulates innate and acquired immune responses. Applied ×3 a week on alternate nights and washed off 10–16 hours later, for up to 16 weeks. Generally takes longer to work than podophyllotoxin. Treatment may be extended beyond 16 weeks if warts are responding. Although some clinical trials have suggested a lower recurrence rate following treatment with imiquimod this is not supported by large comparative RCTs.

• Sinecatechins 10–15% extract of green tea leaf from Camellia sinensis. Catephen®10% ointment was licenced in the UK in 2015. The active ingredient is epigallocatechingallate. Mechanism of action is unclear and comparative trails are lacking, but efficacy appears to be similar to other topical modalities. It is applied ×3 a week for up to 16 weeks.

Fig 23.2 Treatment algorithm for genital warts in men

• Cryotherapy: liquid nitrogen spray (–180°C), swab (–20°C) or probe (–196°C), nitrous oxide probe (–75°C), or carbon dioxide snow (–79°C) may be used to freeze (for ~20–30 seconds) the wart(s) and a margin (‘halo’) of 1–3 mm of surrounding epithelium. The depth of freezing achieved is variable and operator-dependent. Local anaesthetic is not usually needed, but may be required depending on pain tolerance and extent of warts. Adequate cryotherapy causes immediate erythema followed in a few hours by blistering due to cytolysis of the epithelial cells. Healing takes 7–10 days with minimal scarring. If the treated area is large, severe ulceration may occur causing wound-care problems and scarring. Cryotherapy may be repeated at 1–2-week intervals.

• Trichloroacetic acid (TCA): caustic agent causes chemical coagulation leading to necrosis. Applied once a week as an 80–90% solution (unlicensed), ensuring protection of surrounding epithelium with petroleum jelly. A neutralizing agent, e.g. sodium bicarbonate should be available. May be combined with cryotherapy and can be used in most anatomical sites. Treatment-induced pain, ulceration, irritation, and scarring limit its use. Not recommended for large volume warts.

• Electrosurgery: tissue destruction by electrically produced heat. Common methods include:

• electrocautery—application of heat to warts and surrounding tissue under local anaesthesia

• hyfrecation—high-frequency (0.5–3 MHz) low-power (1–30 W) electricity heats the tissue causing necrosis. Patient return electrode (‘diathermy pad’) is not needed since low power is used. Two techniques are used—electrofulguration (current sparks across an air gap) and electrodessication (electrode in contact with or penetrating warts). Requires local anaesthesia.

• surgical diathermy—high-frequency (0.5–3 MHz) high-power (up to 400 W) electricity (requiring ‘diathermy pad’) to produce coagulation or cutting. More suitable for large warts. Requires general anaesthesia.

• Excision: using scalpel, curette, or scissors under local anaesthesia. Haemostasis can be achieved with electrosurgery or paste (e.g. ferric subsulfate–Monsels solution). Very effective and probably under-used treatment option.

• Laser therapy: vaporization of warts under local or general anaesthesia using CO2 or diode laser. Particularly useful for treating warts in anatomically difficult sites, such as urethral meatus and anal canal. Also useful for large volume warts.

• 5-Fluorouracil 5% cream: pyrimidine analogue inhibiting RNA/DNA synthesis. Associated with severe local reactions, including chronic neovascularization and vulval burning. It may also be teratogenic and is not recommended for routine management.

• Interferons: various regimens have been described using interferon α, β, or γ, as intralesional or systemic injection. Local use seems to be more effective than systemic. Use is limited by a variable response rate, systemic side-effects, and expense. Cyclical low-dose intralesional injections used as an adjunct to laser therapy have been reported to reduce relapse rate, although further research is required and interferons are not recommended for routine management.

• Podophyllin resin 15–25%: no longer a recommended treatment. It is less effective than podophyllotoxin and has a worse side effect profile.

The use of clinic-based cryotherapy with home-based podophylotoxin or imiquimod is sometimes used. There is little evidence to support this. It may result in more rapid initial clearance of warts, but has not been shown to be superior with regards to long-term clearance rates.

Current sexual partner(s) may benefit from assessment for undetected genital warts and other STIs, and there may be a need for explanation and advice about disease process.

• Pregnancy: women with sub-clinical infection may develop warts in pregnancy.  in wart volume at delivery is desirable to reduce the level of exposure of the neonate to HPV. However, eradication is difficult, due to the reduced immune response, and treatment may not be the best management option. Cryotherapy, TCA, excision, electrocautery, and laser vaporization are suitable options. Caesarean section is not indicated to prevent vertical transmission. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in the infant is a rare complication of maternal HPV infection. Very rarely Caesarean section may be indicated because of obstruction.

in wart volume at delivery is desirable to reduce the level of exposure of the neonate to HPV. However, eradication is difficult, due to the reduced immune response, and treatment may not be the best management option. Cryotherapy, TCA, excision, electrocautery, and laser vaporization are suitable options. Caesarean section is not indicated to prevent vertical transmission. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in the infant is a rare complication of maternal HPV infection. Very rarely Caesarean section may be indicated because of obstruction.

•  Podophyllotoxin and 5-fluorouracil are contraindicated because of possible teratogenic effects. Imiquimod is not licensed for use in pregnancy as no safety data is available.

Podophyllotoxin and 5-fluorouracil are contraindicated because of possible teratogenic effects. Imiquimod is not licensed for use in pregnancy as no safety data is available.

• Vagina: treatment may not be necessary, especially if warts are small or asymptomatic. Cryotherapy is the usual first-line therapy. Electrosurgery, TCA, podophyllotoxin (not licensed for internal use, total area treated <2 cm2 weekly), or gynaecological referral are other options.

• Routine colposcopy in women with cervical warts is not recommended. If there is diagnostic uncertainty however colposcopy ± biopsy in women of any age is indicated to exclude cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN). Cryotherapy, electrosurgery, TCA, laser ablation or excision are options if required (no treatment is also an option).

• Cytology—no changes to routine screening intervals necessary.

• Urethral meatus: if base of lesions seen, preferred treatment is cryotherapy or electrosurgery. Other options are podophyllotoxin or imiquimod, but use with caution. Deeper lesions require surgical ablation under direct vision.

• Anal canal: surgical excision or laser preferred. If small and accessible—cryotherapy, TCA, electrosurgery.

• Immunosuppressed patients: poor treatment response,  relapse, and dysplasia more likely with

relapse, and dysplasia more likely with  cell-mediated immunity, e.g. following renal transplant or HIV infection. Careful follow-up required.

cell-mediated immunity, e.g. following renal transplant or HIV infection. Careful follow-up required.

Virus-like particle (VLP), the capsid without dna, is immunogenic but non-infectious. Three vaccines using VLP to induce immunity have been shown by trials to be effective. Gardasil® is a quadrivalent vaccine licensed for use in ♂ and ♀ from age 9. It is 99% effective in preventing infection from HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18. It has been used in the UK since 2012 as part of the National HPV Immunization Programme for girls. In 2018 this was extended to include boys aged 12–13 years and MSM up to and including 45 years of age. Cervarix® is a bivalent vaccine providing protection against HPV 16 and 18 and was used in the UK vaccination programme 2008–2012. Gardasil9® provides protection against HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 35, 45, 52, and 58, and received a licence in Europe in 2015. In countries where the quadrivalent vaccine has been used there have been large reductions in the rate of genital wart diagnoses in the vaccinated population. In the UK, rates of first diagnosis of genital warts in 15–19-year-old females dropped by 38.9% between 2009 and 2015. Reductions were greatest among 15-year-old girls (83.2%) who were largely offered Gardasil®. A reduction of 30.2% was also seen in 15–19-year-old heterosexual males, illustrating herd immunity. Cervarix® and, to a lesser degree, Gardasil® provide some cross-protection against HPV types 31, 33, 45, and 58 (92%, 52%, 100%, and 65% with Cervarix®). All 3 vaccines are licensed for the protection of individuals against genital infection and associated disease related to HPV vaccine types. None of the vaccines are licensed for treatment of existing HPV infection or HPV-related disease. Studies to assess the effect of the vaccines in those already sexually active or HPV-infected are being conducted. Following Gardasil® vaccination, a retrospective pooled analysis of women with previously treated warts showed disease recurrence. There is also evidence of regression of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN)-related disease in young vaccinated ♀.

It is advisable not to treat warts at home with over-the-counter preparations. These preparations are designed for use on hands or feet, and may damage genital skin.

There are special prescription-only preparations (podophyllotoxin and imiquimod) for home use, although the treatments recommended depend on the position, number, and appearance of the warts.

The HPV types that usually cause genital infection almost exclusively favour this site and so are sexually transmitted. However, occasionally, other types, such as those causing warts on the hands, can be spread to the genitals and have been found in children.

Warts are common in pregnancy, often grow more quickly, and are more difficult to manage as certain treatments cannot be used. They often resolve spontaneously after the pregnancy is over. Although HPV can be transmitted to babies at delivery it is unusual. Treating the warts will not remove the underlying infection.

• HPV infection has not been associated with  risk of HIV acquisition.

risk of HIV acquisition.

• Those with HIV infection appear to be at greater risk of acquiring or reactivating HPV.

• Oral warts (due to HPV types 7, 13, 18, and 32) are more common in those with HIV infection.

• Duration and natural history of concurrent HPV infection may be altered, leading to  incidence of cervical and anal neoplasia.

incidence of cervical and anal neoplasia.

Futher information

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV guideline on Anogenital warts  https://www.bashh.org/guidelines

https://www.bashh.org/guidelines