Introduction

ART has dramatically improved prognosis and life expectancy of PLWH. Many of the newer antiretrovirals (ARVs) are better tolerated with several combination tablets available, improving quality of life and reducing pill burdens.

The main principles of management of PLWH include:

• engaging and maintaining patients in regular follow-up with HIV specialist care

• prognosis improved by early initiation of ART, regardless of CD4 count, VL or symptoms

• patient views, social history and lifestyle, medical history, mental health, co-medications, and recreational drug use should be considered when choosing ARV regimen.

• patient readiness and adherence support should be discussed.

• baseline resistance testing, HLAB*57:01 status, co-infection, e.g. with HBV, HCV, or TB will also influence drug choice.

With effective ART, PLWH are living longer and many of the issues seen in routine follow-up are co-morbidities seen in the general population, social issues, and mental health issues, as well as problems with polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions. Side effects of ART can still be problematic; for some, direct symptoms of HIV or opportunistic infections are less common.

When to start

Early initiation of treatment is associated with improved outcomes, and is recommended to all, irrespective of CD4 count, with the possible exception of elite controllers with stable high CD4 counts. However, patients need to be ready to take on the commitment of lifelong treatment, as poor adherence and breaks from treatment are associated with worse outcomes.

Primary HIV infection

PHI is defined as the first 6 months following acquisition of the virus. PHI may be diagnosed according to symptoms of seroconversion, previous –ve HIV test within the last 6 months, history of HIV contact, etc. During PHI, the HIV VL is at its highest and there is, therefore, a high risk of transmission. Initiating treatment during this phase reduces the reservoir of HIV, which can improve long-term outcomes.

Treatment as prevention

Strong evidence (including PARTNER study) has shown that PLWH who have sustained viral suppression with good adherence to effective ART will not transmit HIV infection. Condoms are still recommended to protect against other STIs and unplanned pregnancy.

Opportunistic infections

People presenting with CD4 count <200 cells/µL, AIDS defining infection, or other serious infection, should be started on ART within 2 weeks. This has been shown to improve survival; however, those with intracranial OIs, particularly cryptococcal meningitis, may be more at risk of developing immune reconstitution disorders, so consider delaying ART initiation.

Chronic infection

Where a patient is not ready to commit to treatment, or for other reasons where it is thought best to delay initiation, treatment may be delayed until before the CD4 count is <350 cells/µL

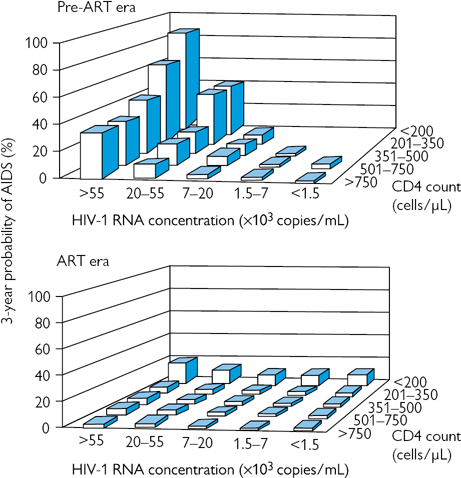

In asymptomatic patients, the likelihood of developing AIDS over a 3-year period can be predicted according to VL and CD4 count (Fig. 55.1) CD4 count is the best indicator of OI risk, but high VLs are associated with more rapid rates of CD4 fall. Patients who have not done so already should be strongly encouraged and supported to start ART when they have:

• symptomatic HIV

• neurological symptoms

• AIDS-defining illness regardless of CD4 count

• Before CD4 count reaches 350 cells/µL or <14%.

Hepatitis B or C co-infection

ART should be offered to all patients with HBV or HCV co-infection. ART should not be delayed, particularly if HBV requires treatment and should be initiated before treatment for HCV where this is required, unless CD4 count >500 cells/µL.

TB co-infection

In patients diagnosed with TB and HIV infection, simultaneously, anti-tuberculosis treatment (ATT) should be initiated as soon as possible. Treatment of HIV should be started as soon as possible; however, it can be complicated by drug interactions with ATT, so if the CD4 count is >100 cells/µL, ART may be delayed until 8–12 weeks into ATT. If CD4 <50 cells/µL, ART should be started within 2 weeks, where possible.

Malignancy

All PLWH diagnosed with a malignancy, whether or not it is HIV associated, should commence ART alongside any cancer specific therapy. Drug–drug interactions must be taken into account

How to start

Many factors should be considered prior to treatment initiation. Discussion with the patient regarding the advantages of treatment, uninterrupted lifelong treatment, the importance of adherence, and ways to support this, potential for drug interaction, including recreational drugs and important side effects. Involvement of patient in decision-making is essential.

Baseline blood tests as a minimum should include:

• CD4 count and VL

• HIV viral resistance testing

• Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) B*57:01 if abacavir considered

• FBC, renal, including eGFR, and LFTs.

Patient history

• co-morbidities (renal, liver, cardiovascular, osteoporosis, psychiatric, substance misuse)

• co-infection (HBV, HCV, TB)

• pregnancy, pregnancy planning, and contraceptive needs

• drug history, including over the counter and recreational drugs.

Regimen specific factors

• potential side effects

• genetic barrier to resistance

• DDIs

• convenience

• cost.

Top tip

Always check for drug interactions using a reliable database, such as the University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions website. Advise patients and GPs to check for drug interactions before introducing new medications  www.hiv-druginteractions.org

www.hiv-druginteractions.org

Adherence

Treatment adherence is essential for successful viral suppression as sub-therapeutic drug levels select for HIV-resistant mutations arising from error-prone viral replication. Improving adherence is more cost effective than managing the consequences of poor compliance. Most patients are non-adherent sometimes and this is influenced by various factors, intentional, or unintentional:

• cultural/social beliefs

• mental health

• drugs and alcohol abuse

• stigma of taking medication

• relationship with healthcare team

• symptoms and side effects

• socioeconomic status and poor diet.

Supporting adherence

• Involve patients in treatment decisions and help them understand the reasons for taking medication, as well as possible adverse effects.

• Enquire about adherence in a non-judgmental way, whenever ART is discussed, prescribed, or dispensed.

• Address barriers, such as culture/beliefs, psychosocial factors, drugs, and alcohol use.

Interventions to improve adherence

Address any misconceptions or concerns regarding treatment. If side effects are an issue, alternative dosing, timing, regimen, or simplification should be considered. Some side effects may be treated through, e.g. nausea or diarrhoea, and may need further medication to control. Practical solutions, such as pill apps, alarms, text message reminders, and medication boxes can help. Adherence support from specialist nurses, pharmacists, or peer support groups should be considered.

Top tip

When enquiring about adherence ask, ‘When was the last time you missed your medication?’ or ‘How many times have you missed your medicines in the last month?’ rather than ‘Do you take all your medicines’.

What to start

There are currently 6 different classes of antiretroviral drugs that inhibit the virus at different stages of viral replication (Fig. 55.2):

• interaction with CD4 receptors–fusion/CCR5 inhibitors

• inhibition of reverse transcriptase, which converts viral RNA to pro-viral DNA –NRTI and NNRTI;

• inhibition of post-transcribed viral DNA into the host DNA-integrase inhibitors;

• inhibition of protease involved in assembly of infective virions–protease inhibitors (PIs).

Combination therapy

Triple therapy is the standard of care. There are now over 30 licensed ARVs with many combination tablets available (Table 55.1). Treatment choice is guided by the differing tolerability, side effects, drug interactions, impact on co-pathologies, as well as individual resistance profile, VL, CD4 count, and convenience. Recommended treatment combinations includes 2 NRTIs (the backbone) + a third agent from another class of ARV (Table 55.2). Dual therapy regimes are being studied and effective regimes include DTG/RPV as a switch and DTG/3TC in naive patients with VL <100,000.

Table 55.1 Antiretroviral combination tablets

| Combination tablet |

Drug components |

| Triple combinations |

Atripla® |

tenofovir DF/emtricitabine/efavirenz |

| Biktarvy® |

bictegravir/tenofovir AF/emtricitabine |

| Eviplera® |

tenofovir DF/emtricitabine/rilpivirine |

| Genvoya® |

tenofovir AF/emtricitabine/elvitegravir/cobicistat (COBI) |

| Odefsey® |

tenofovir AF/emtricitabine/rilpivirine |

| Stribild® |

tenofovir DF/emtricitabine/elvitegravir/COBI |

| Symtuza™ |

darunavir/COBI/tenofovir AF/emtricitabine |

| Triumeq® |

abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir |

| (Trizivir) ® |

(abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine) |

| Dual combinations |

Combivir® |

zidovudine/lamivudine |

| Descovy® |

tenofovir AF/emtricitabine |

| EvotazTM |

atazanavir/COBI |

| Juluca® |

dolutegravir/rilpivirine |

| Kaletra® |

lopinavir/ritonavir |

| Kivexa® |

abacavir/lamivudine |

| Rezolsta® |

darunavir/COBI |

| Truvada® |

tenofovir DF/emtricitibine |

Table 55.2 Recommended first-line ARV regimens

|

Preferred choice |

Alternative |

| Backbone |

Tenofovir1 + emtricitibine |

Abacavir2 + lamivudine |

| Plus |

Atazanavir/ritonavir |

Efavirenz |

| third agent |

Elvitegravir/COBI |

|

|

Darunavir/ritonavir |

|

|

Darunavir/COBI |

|

|

Dolutegravir |

|

|

Raltegravir (RAL) |

|

|

Rilpivirine2 |

|

1 Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or Tenofovir alafenamide.

2  Table 55.3 for prescribing restrictions.

Table 55.3 for prescribing restrictions.

Common characteristics of ARVs are outlined in Table 55.3, including prescribing restrictions.

Table 55.3 Characteristics of commonly used antiretrovirals

| ARV |

Dosing* |

Prescribing considerations |

| NRTIs |

| Abacavir (ABC) |

600 mg od |

Avoid if +ve for HLA*B57:01. Hypersensitivity reaction associated with HLA*B57:01 can be fatal. Do not re-challenge

Avoid if VL >100K, unless combined with boosted DTV. Caution if CVS risk or hepatic impairment Avoid if +ve for HLA*B57:01. Hypersensitivity reaction associated with HLA*B57:01 can be fatal. Do not re-challenge

Avoid if VL >100K, unless combined with boosted DTV. Caution if CVS risk or hepatic impairment |

| Emtricitabine (FTC) |

200 mg cap od |

Dose reduce if eGFR <50. Avoid FTC/TDF if eGFR<30

SEs rare

Rarely lactic acidosis, hepatic steatosis |

| Lamivudine (3TC) |

300 mg od |

Dose reduce if eGFR <50

SEs rare: lactic acidosis, hepatic steatosis |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TFD) |

300 mg od |

Dose reduce if eGFR <50. Avoid if eGFR<30. Caution if osteoporosis

Can cause renal impairment and altered bone metabolism |

| Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) |

25 mg od |

Approved as part of fixed drug combinations,  Table 55.1 Table 55.1

dose compared with TDF so  adverse effects on bone and kidneys adverse effects on bone and kidneys |

| Zidovudine (AZT) |

300 mg bd |

Dose if eGFR <15

IV or oral administration

Bone marrow suppression, myopathy, lactic acidosis, hepatic steatosis |

| NNRTIs |

| Efavirenz (EFV) |

600 mg od |

Avoid if history of mental illness or neurological symptoms

Cost as generics available

CNS (vivid dreams) and psychiatric SEs (depression, suicidality),  lipids, rash lipids, rash |

| Rilpivirine (RPV) |

25 mg od |

Avoid if VL>100K as  failure rate

Should be taken with ≥350 kcal meal failure rate

Should be taken with ≥350 kcal meal

SE than EFV. No significant drug–drug interactions (DDI) with hormonal contraceptive

CNS, lipid, and rash side effects |

| Nevirapine (NVP) |

200 mg bd |

Avoid if CD4 >250♀ or CD4>400♂

SE rash, Steven–Johnson’s, hepatitis |

| Etravirine (ETV) |

200 mg bd |

No dose adjustment for renal or hepatic impairment

Barrier to resistance

Rash, diarrhoea |

| Integrase inhibitors (INI) |

| Elvitegravir (EVG) |

150 mg od in Stribild® varies with regimen |

Administered with COBI. Avoid Stribild® if eGFR <70 and in severe hepatic impairment

Comes as part of STR Stribild®

DDI due to COBI |

| Dolutegravir (DTV) |

50 mg od |

Avoid co-administration with bi-ionic cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, etc.)

Genetic barrier to resistance

SEs,  DDI

Insomnia, headache DDI

Insomnia, headache |

| Raltegravir (RAL) |

400 mg bd

or 1200 mg od |

BD or OD dosing.

Avoid co-administration with bi-ionic cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, etc.)

Well tolerated,  DDI

Compliance issues DDI

Compliance issues |

| Bictegravir |

50 mg od |

INI in Biktarvy part of fixed dose regimen

Biktarvy has high genetic barrier to resistance

DDI |

| PIs# |

| Atazanavir (AZV) |

300/400 mg od |

Administer with ritonavir (RTV) or COBI (300 mg when boosted,)

>10-year safety data in pregnancy

Bilirubin,  PR interval, DDI PR interval, DDI |

| Darunavir (DRV) |

800 mg od |

Administer with RTV or COBI. Not recommended in severe liver failure.

barrier to resistance,  half life

GI side effects, lypodystrophy, DDI half life

GI side effects, lypodystrophy, DDI |

| Entry inhibitors |

| Enfuvirtide (ENF) |

90 mg SC bd |

Licensed for treatment failure, rarely used. Useful when other options exhausted as part of salvage regime

Injection site reactions common, hypersensitivity,  pneumonia pneumonia |

| Maraviroc (MVC) |

Dose depends on ARV regimen |

Only effective if CCR5 Tropic. Requires tropism testing (VL must be >1000)

Useful when other options exhausted as part of salvage regime |

| Pharmacokinetic boosters |

| Cobicistat (COBI) |

150 mg od |

Must be co-administered with ARV. Booster only. No ARV activity alone

Reduces dose of boosted ARV

Alters creatinine clearance without affecting renal function. DDIs |

| RTV |

100 mg od |

Used as a booster in combination with other PI

GI side effects. DDIs |

* Oral unless otherwise stated.

# Other PIs are available—they are rarely used first-line, but are still used by some patients.

Monitoring and follow-up

Side effects of ARVs are common; however, many resolve within a few weeks, while others can persist. Psychosocial issues are often present and can impact on well-being and compliance. Also, with effective modern therapy, people living with HIV are ageing, with consequent co-morbidities common. Routine review aims to detect any issues arising and dealing with them in order to promote psychological and physical well-being, and quality of life (See Table 55.4 for suggested schedules).

Table 55.4 Schedule of routine monitoring and investigations

| Assessment of patients starting and established on ART |

Baseline |

2–4 weeks |

12 weeks |

6 monthly |

Annual |

3-yearly |

As indicated |

| History |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Medical history |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| • Mental health |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

| • Neurocognitive |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| • Sexual history, partners |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

| • Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Contraception, conception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Social history |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Smoking, alcohol, deprivation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Travel history |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| • IGRA2,1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Tropical screen1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Medication |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

| • Prescribed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Recreational |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Non-prescribed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Herbal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Adherence |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| • Side effects |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Vaccination history |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Family history |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Patient ideas/concerns |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Examination |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • General physical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| • Blood pressure |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| • BMI3 |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Investigations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Viral load4 |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

| • CD4 count5 |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| • HIV resistance |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

| • HLAB*57:01 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| • Tropism |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Viral serology |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Hep A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Hep B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| • Hep C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| • Measles1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Varicella1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Rubella1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| STI screen + syphilis |

✓ |

|

✓6 |

|

|

|

✓ |

| • Blood monitoring |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| • FBC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • U&E, eGFR |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| • LFT, Bone |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| • Lipids, HbA1c >40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Urinalysis |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

| Cervical cytology

♀25–64 |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Risk assessments |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Cardiovascular >40 years |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| • Fracture risk >50 years |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

1 Depending on travel/vaccination history;

2 interferon gamma release assay (IGRA);

3 body mass index (BMI);

4 if ART being used for ‘treatment as prevention’, 3–4 monthly monitoring may be required;

5 see Monitoring CD4 cell count box  ‘Monitoring CD4 cell count’, p. 633;

‘Monitoring CD4 cell count’, p. 633;

6 depending on sexual risks.

Routine tests

• Renal (+ eGFR), liver and bone profiles, and FBC are measured routinely in order to detect adverse effects of ARVs. If eGFR  urine protein/creatinine ratio should be measured.

urine protein/creatinine ratio should be measured.

• Lipids and HbA1c are measured annually in patients >40 in order to detect signs of metabolic syndrome as HIV and ART adversely affect cardiovascular risk

• CD4 cell count usually  with

with  VL, initially as a result of re-circulated reserves. Long-term CD4 count depends on the ability of the thymus to produce new T cells. Immune reconstitution is variable and often depends on the extent of immunosuppression at the time of ART initiation.

VL, initially as a result of re-circulated reserves. Long-term CD4 count depends on the ability of the thymus to produce new T cells. Immune reconstitution is variable and often depends on the extent of immunosuppression at the time of ART initiation.

• VL suppression to <1000 copies/mL is usually achievable by 4 weeks regardless of initial VL or ARV regimen, and VL <50 copies/mL is a sign of successful treatment, which should be achieved by 3–6 months. Ongoing VL monitoring is required to ensure ongoing treatment success.

Therapy specific tests

• TDF can cause renal tubular toxicity with phosphate wasting and rarely Fanconi’s syndrome; therefore, careful renal monitoring is required and switching therapy may be required if renal function declines or there is evidence of renal tubular dysfunction. TAF does not have this same effect as renal tubular cell uptake and dosing is significantly less.

• HLAB*57:01 typing should be performed prior to considering abacavir treatment. HLAB*57:01 is present in 5% Caucasians, but rare in sub-Saharan Africans and is associated with hypersensitivity reaction. If HLAB*57:01 positive abacavir should not be started.

• Tropism testing should be carried out only if treatment with maraviroc (CCR5 antagonist) is being considered. Routine testing is not indicated, and tropism can change over time so historic tests would need repeating. Only patients with CCR5 tropic virus should be started on maraviroc.

Monitoring CD4 cell count

Perform CD4 cell count at baseline. If ART not initiated, monitor yearly if CD4 >500 cells/mL and 6 monthly if <500 cells/mL.

For patients established on ART

• If CD4 <200 cells/mL monitor 3–6-monthly

• If CD4 200–350 measure 6–12-monthly

• If CD4 cell count >350 for >1 year routine monitoring not required.

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM)

Routine TDM is not recommended, although in certain situations it may be useful:

• Drug interactions: to monitor plasma concentrations, which may be altered by drug interactions.

• Children, pregnant ♀, and in older patients where pharmacokinetics may be altered.

• Extremes of weight.

• Unexplained VL  : TDM in therapeutic range does not exclude non-adherence, but absent or low levels can help confirm it.

: TDM in therapeutic range does not exclude non-adherence, but absent or low levels can help confirm it.

• Blood sampling (plasma) should ideally be at the end of the dosing interval (Cmin) in patients established on treatment ≥14 days.

Vaccinations

People with HIV with CD4<200 have  response to non-replicating vaccines and risk of vaccination-related disease with replicating vaccines. PLWH are at increased risk of other vaccine preventable infections such as HBV, HAV, pneumococcal illness, influenza so these should be routinely offered and/or immunity checked (see Table 55.5).

response to non-replicating vaccines and risk of vaccination-related disease with replicating vaccines. PLWH are at increased risk of other vaccine preventable infections such as HBV, HAV, pneumococcal illness, influenza so these should be routinely offered and/or immunity checked (see Table 55.5).

• If CD4 <200 replicating vaccinations contraindicated.

• If CD4 200-350 immune response is suboptimal so balance urgent need for immunization with better response when  CD4.

CD4.

• Co-administration of replicating vaccines not advised – give 4 weeks apart.

• Replicating vaccines should not be given ≤2 weeks before or ≤12 weeks after blood products containing antibodies.

Table 55.5 Vaccinations for people living with HIV

|

Infection |

Vaccine type |

Recommendation |

| Recommended |

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis A

Influenza

Pneumococcal |

Subunit

Inactivated

Inactivated

PCV13 Conjugated |

All non-immune

All at risk

All annually

All once |

| Caution |

Measles, mumps, rubella

Varicella

Herpes zoster

Yellow fever |

Live attenuated |

Avoid if CD4 <200

If CD4 >200 give as per Green Book recommendations  Further information, below Further information, below |

| Avoid |

Influenza

Typhoid

TB |

Live attenuated

Live attenuated

BCG |

Intranasal; not preferred

Contraindicated

Contraindicated |

Further information

• The Green Book (immunization against infectious disease):  www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book

www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book

• British HIV Association guideline on use of vaccines in HIV positive adults:  https://www.bhiva.org/vaccination-guidelines

https://www.bhiva.org/vaccination-guidelines

Switching antiretroviral therapy

Switching ARVs may be necessary for a number of reasons, such as side effects/toxicity, adherence issues, or failing therapy. Considerations depend on whether or not VL is suppressed and whether there are any drug interactions between the original regimen and the new regimen ARVs. In particular, NNRTIs efavirenz and nevirapine are enzyme inducers, with effects likely to last for a while after drug cessation.

• If VL is fully suppressed direct switch can be made.

• If switching to PI or integrase inhibitor (INI), direct switch can be made.

• If viral replication ongoing and switching away from NNRTI, switch to boosted PI (COBI or RTV)-containing regimen, and not to other NNRTI.

• For other switches in the presence of ongoing viral replication, seek specialist advice.1

1 See also  http://www.bhiva.org/HIV-1-treatment-guidelines.aspx

http://www.bhiva.org/HIV-1-treatment-guidelines.aspx

Stopping antiretroviral therapy

Stopping ART is not recommended, but in rare circumstances, such as drug toxicity, intercurrent illness, patient choice, or post-partum, it may be necessary. Due to differing half-life of different ARVs, stopping all drugs simultaneously may lead to effectively mono- or dual- therapy of the drugs with longer half-life, which can lead to drug resistance. The different approaches include:1

• stopping simultaneously if PI-based regimen or regimen containing ARVs with similar half-lives

• staggered stopping for regimen containing ARVs with long and short half-lives

• replacing all ARVs with boosted PI (e.g. darunavir with RTV or COBI) for 4 weeks if regimen contains ARVs with long and short half-lives, e.g. NNRTI and NRTI regime.

Antiretroviral side effects

Many side effects historically associated with ARVs were caused by drugs that have been discontinued or rarely used. Newer agents tend to be better tolerated, but side effects are still common, and side effects of discontinued ARVs may persist.

ABC hypersensitivity

Occurs in 4% (almost always associate with HLAB*57:01), usually within first 6 weeks. Usually presents with >2 of GI symptoms, headache, fever, rash, abnormal LFTs, myalgia, respiratory symptoms, and eosinophilia. If suspected, discontinue ABC immediately, give supportive care. Symptoms resolve within 24–48 hours, rash may take longer. Do not re-challenge with ABC as risk of mortality.

Gastrointestinal disturbance

Nausea and diarrhoea are common, especially in the first days/weeks of most ARVs, but especially PIs, which may cause persistent diarrhoea. Anti-emetics and/or loperamide may alleviate symptoms.

Hepatotoxicity

Can be caused by most ARVs.  ♂ and those with other risk factors, e.g. alcohol excess, HBV/HCV co-infection. Graded 1 (ALT 2–3× normal upper limit) to 4 (>10× normal upper limit). Most common with DDI, stavudine (D4T), AZT, ABC, NVP, EFV, and RTV. If minor abnormality only monitoring required. If severe, stop offending ARV. If caused by ABC or NVP, do not re-challenge.

♂ and those with other risk factors, e.g. alcohol excess, HBV/HCV co-infection. Graded 1 (ALT 2–3× normal upper limit) to 4 (>10× normal upper limit). Most common with DDI, stavudine (D4T), AZT, ABC, NVP, EFV, and RTV. If minor abnormality only monitoring required. If severe, stop offending ARV. If caused by ABC or NVP, do not re-challenge.

Lipodystrophy

Found in ~4% untreated PLWH.

• Lipohypertrophy: central adiposity, ‘buffalo hump’, lipomas,  neck circumference—associated with PIs.

neck circumference—associated with PIs.

• Lipoatrophy: peripheral and facial subcutaneous fat loss—associated with older NRTIs particularly D4T, can be stigmatizing.

• Dyslipidaemia:  total cholesterol and/or

total cholesterol and/or  triglycerides—reported in <80% taking ARVs, associated with PIs, especially RTV, and older PIs.

triglycerides—reported in <80% taking ARVs, associated with PIs, especially RTV, and older PIs.

Mitochondrial toxicity

May present with nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, hepatic steatosis, myopathy, neuropathy, lactic acidosis. Mainly associated with AZT, D4T, and DDI. Switch to alternative ARVs and supportive care recommended.

Neuropathy

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSP) can be difficult to distinguish from HIV-related DSP, but tends to be painful, more sudden, and progressive. Discontinue offending ARV and, if needed, offer pain relief with tricyclic antidepressants or gabapentin.

Neuro-psychiatric

Can manifest as depression and other mood disorders, insomnia, vivid dreams, dizziness. Common with EFV and DTV. May settle or patients become accustomed, but can persist long term. Switch to alternative ARV if severe or affecting quality of life.

Rash

Rash is common especially with NNRTIs and ABC  Table 55.3. NVP rash, typically maculopapular, affecting trunk, occurs in first 2 weeks of therapy and risk is minimized by half-dose induction for first 2 weeks. Mild rash does not require intervention and will usually settle. Antihistamine for symptom relief. If severe or SJS (mucous membranes involved) switch to alternative ARV.

Table 55.3. NVP rash, typically maculopapular, affecting trunk, occurs in first 2 weeks of therapy and risk is minimized by half-dose induction for first 2 weeks. Mild rash does not require intervention and will usually settle. Antihistamine for symptom relief. If severe or SJS (mucous membranes involved) switch to alternative ARV.

Renal impairment and Fanconi’s syndrome

Renal tubular dysfunction, tubule-interstitial nephritis, and Fanconi syndrome are most commonly associated with TDF, but also ATV.  eGFR, proteinuria or persistent significant hypophosphataemia may be initial signs. Switch to alternative ARV if possible.

eGFR, proteinuria or persistent significant hypophosphataemia may be initial signs. Switch to alternative ARV if possible.

Creatinine seen with DTV, RAL, COBI, RPV, RTV occurs 2–4 weeks after starting, is non-progressive, and due to altered creatinine transport. It is not associated with altered kidney function.

Creatinine seen with DTV, RAL, COBI, RPV, RTV occurs 2–4 weeks after starting, is non-progressive, and due to altered creatinine transport. It is not associated with altered kidney function.

Immune reconstitution

ART leads to  viral replication and

viral replication and  VL, with subsequent

VL, with subsequent  CD4, initially due to

CD4, initially due to  memory cells followed by

memory cells followed by  naïve CD4 cells. CD8 cells initially

naïve CD4 cells. CD8 cells initially  , but then

, but then  . ART causes

. ART causes  HIV specific immune response, but

HIV specific immune response, but  immune response to other pathogens, with

immune response to other pathogens, with  OIs with

OIs with  CD4. Lower CD4 nadir usually results in slower and less complete immune recovery.

CD4. Lower CD4 nadir usually results in slower and less complete immune recovery.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory response

Aetiology is thought to be the result of immune reconstitution with abnormal response to an underlying pathogen. It is characterized by worsening or appearance of new clinical signs/symptoms after initiation of ART, and is not the result of treatment failure, drug hypersensitivity, malignancy, or other disease processes. It may appear as a paradoxical worsening after treatment of a known OI, such as TB (paradoxical IRIS), or as symptoms of a previously unknown OI (unmasking IRIS). It appears ≤12 weeks after ART and occurs in 11–36% TB/HIV co-infected patients. IRIS is also seen with CMV, MAC, HCV, HSV, cryptococcal meningitis, and progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy.

Clinical features of TB IRIS include fever, lymphadenopathy +/–overlying redness, worsening pulmonary lesions, pleural effusion/ascites, abscesses cutaneous lesions, CNS tuberculoma. May be transient or last for months. It is more likely if low nadir CD4 with rapid  CD and rapid

CD and rapid  VL following ART, disseminated infection and early ART initiation.

VL following ART, disseminated infection and early ART initiation.

Management

Exclude other cause, start/continue treatment of OI. If severe, high dose corticosteroids (e.g. 1–1.5 mg/kg prednisolone) may be required for variable duration. May recur when steroids discontinued, so gradual reduction recommended.

Antiretroviral drug–drug interactions

Interactions with ARVs are common, so always check for DDIs before co-administering  www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

Common interactions are described in Table 55.6.

HIV drug resistance

There are different mechanisms for ARV drug resistance:

• Intrinsic drug resistance, such as HIV-2 resistance to NNRTIs.

• Transmitted drug resistance (TDR) occurs when the transmitted HIV has resistance mutations. In the UK, TDR rate is 10%, greatest in London. TDR for integrase inhibiter (INI) is very low.

• Resistance may also be acquired following poor adherence, drug interaction or poor absorption leading to treatment failure.

• ~70% of virological failure is not due to ARV resistance, but 2° to poor adherence, DDI, or malabsorption.

Development of HIV drug resistance

HIV has a high rate of replication (unhindered 108–10 virions produced daily) and replication is error-prone with one mutation on average per replication cycle. Therapeutic drug levels will reduce resistance mutations occurring by inhibiting viral replication and suppressing existing mutations if they are not resistant to all drugs in the ARV regimen. However, if drug levels are sub-therapeutic, the on-going viral replication will select for mutations that can overcome the ARVs present. Resistance to some ARVs occurs with only a small number of mutations (low barrier to resistance, e.g. NNRTIs), while others require several cumulative mutations to develop before resistance is seen (high barrier to resistance, e.g. boosted PIs). Even with undetectable VL, low-level replication may allow resistance to develop. Compensatory mutation reverses  viral fitness resulting from other mutations. Some mutations induce resistance to certain agents, while simultaneously producing hypersusceptibility to others (e.g. M184V causes resistance to 3TC, but

viral fitness resulting from other mutations. Some mutations induce resistance to certain agents, while simultaneously producing hypersusceptibility to others (e.g. M184V causes resistance to 3TC, but  sensitivity to AZT). Drug resistance has been demonstrated in up to 25% of patients on ART.

sensitivity to AZT). Drug resistance has been demonstrated in up to 25% of patients on ART.

Resistance mutations

Resistance mutations are described using a number referring to the affected codon in the HIV genome, preceded by a letter referring to the wild type amino acid, and followed by a letter referring to the mutant amino acid, e.g. L74V is a mutation at codon 74 where leucine has been replaced by valine. (For examples, see Table 55.7.)

Table 55.7 Examples of resistance mutations

| Major NRTI mutations |

|

Non-TAMs |

TAMs1 |

MDR2 |

| Codon |

65 |

70 |

74 |

115 |

184 |

41 |

67 |

70 |

210 |

215 |

219 |

69 |

151 |

| Wild type |

K |

K |

L |

Y |

M |

M |

D |

K |

T |

T |

K |

T |

Q |

| 3TC/FTC |

R |

|

|

|

VI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ins* |

M |

| ABC |

R |

E |

VI |

F |

VI |

L |

|

|

W |

FY |

|

Ins |

M |

| TDF |

R |

E |

|

F |

|

L |

|

R |

W |

FY |

|

Ins |

M |

| AZT/D4T |

|

|

|

|

|

L |

N |

R |

W |

FY |

QE |

Ins |

M |

| Major PI mutations |

| Codon |

30 |

32 |

33 |

46 |

47 |

48 |

50 |

54 |

76 |

82 |

84 |

88 |

90 |

| Wild type |

D |

V |

L |

M |

I |

G |

I |

I |

L |

V |

I |

N |

L |

| ATV |

|

I |

F |

IL |

V |

VM |

L |

V |

|

A |

V |

S |

M |

| DRV |

|

I |

F |

|

VA |

|

V |

LM |

V |

F |

V |

|

|

| Major NNRTI mutations |

| Codon |

100 |

101 |

103 |

106 |

138 |

181 |

188 |

190 |

230 |

| Wild type |

L |

K |

K |

V |

E |

Y |

Y |

G |

M |

| EFV/NVP |

I |

EP |

NS |

AM |

|

CIV |

LCH |

ASE |

L |

| RPV |

I |

EP |

|

|

AGKQ |

CIV |

L |

ASE |

L |

| Major INI mutations |

| Codon |

66 |

92 |

138 |

140 |

143 |

148 |

155 |

263 |

| Wild type |

T |

E |

E |

G |

Y |

Q |

N |

R |

| RAL |

AK |

Q |

KAT |

SAC |

RCH |

HRK |

H |

K |

| DTV |

K |

Q |

KAT |

SAC |

|

HRK |

H |

K |

* Insertion at codon 69.

1 Thymidine analogue mutations (TAM) develop under selective pressure from AZT/D4T.

2 Multidrug resistant mutations. 151 Complex usually occurs with other accessory mutations.

Letters represent the different amino acids. Those in bold represent mutations that cause reduction in ARV susceptibility, those in plain text reduce susceptibility in combination with other mutations.

Resistance mutations are variable in their effect upon viral fitness and their effectiveness in pervading ARV therapy. Resistance can occur rapidly within weeks if only a single mutation confers resistance, e.g. K103N (NVP/EFV-resistant mutation). A mutation may also confer resistance to other ARVs within the same class e.g. M184V (ABC/3TC/FTC resistance). Other mutations may only confer resistance when multiple mutations have accumulated, so resistance develops slowly or not at all, e.g. PI resistance mutations.

Many mutations  viral fitness, e.g. DTV-resistance mutations. However, resistance mutations confer a selective advantage by

viral fitness, e.g. DTV-resistance mutations. However, resistance mutations confer a selective advantage by  susceptibility to antiviral agents, thereby enabling the mutant quasi-species to proliferate under treatment with those agents. Compensatory mutations, e.g. 30N (nelfinavir resistance) may be required to

susceptibility to antiviral agents, thereby enabling the mutant quasi-species to proliferate under treatment with those agents. Compensatory mutations, e.g. 30N (nelfinavir resistance) may be required to  viral fitness.

viral fitness.

Drug resistance patterns

K65R mutation (selected by TDF, ABC and DDI) confers resistance to TDF, ABC, and 3TC and  susceptibility to AZT and D4T. This mutation develops rapidly when regimens combining TDF with two of ABC, DDI, or 3TC are given to the treatment naïve. Co-existence of K65R and M184V

susceptibility to AZT and D4T. This mutation develops rapidly when regimens combining TDF with two of ABC, DDI, or 3TC are given to the treatment naïve. Co-existence of K65R and M184V  resistance to ABC and DDI, but retains suscepti-bility to TDF, AZT, and D4T. Multiple mutations may interact. Resulting resistance patterns can be predicted by matching with resistance profile databases. This is provided by commercial resistance tests.

resistance to ABC and DDI, but retains suscepti-bility to TDF, AZT, and D4T. Multiple mutations may interact. Resulting resistance patterns can be predicted by matching with resistance profile databases. This is provided by commercial resistance tests.

Databases of resistance profiles are available at:

• Stanford Database:  http://hivdb.stanford.edu

http://hivdb.stanford.edu

• ANRS:  http://www.hivfrenchresistance.org

http://www.hivfrenchresistance.org

• REGA:  http://rega.kuleuven.be/cev/regadb/download

http://rega.kuleuven.be/cev/regadb/download

Persistence of mutation/resistance

When treatment that selected for resistant quasi-species is discontinued, wild-type virus usually becomes predominant within 2 months. Drug-resistant mutants occasionally remain dominant, e.g. 41L (zidovudine), but usually cease to be detectable by standard assay. How-ever, they may still persist as minority quasi-species, e.g. 90M (PI), or latent integrated proviral DNA (archived resistance). Therefore, standard assays may not exclude drug resistance, if carried out >1 month after stopping a failing regimen, and may not detect TDR, if performed long after HIV acquisition. Interpretation of resistance mutations must take into account previous treatment history and previous resistance reports.

Resistance testing

Standard resistance assays require VL >500 copies/mL and cannot detect minority species. Expert advice is needed to interpret the results.

Genotyping

Viral genes are sequenced to identify key mutations known to confer (alone or with others) resistance. Current methodology only detects viral mutants comprising at least 20–30% of the total population. Analysis is based on known correlation between genotype and phenotype from previous studies. Results are normally available in 2–4 weeks.

Phenotyping

Viral cell cultures are set up with increasing concentrations of ARTs to determine IC50, the concentration of drug required to inhibit viral replication by 50%. Cut-off value indicates by what factor the IC50 of an HIV isolate can be  , while still being classified as susceptible, compared with a wild-type control. IC50 above this value indicates resistance. Phenotyping is not available in the UK.

, while still being classified as susceptible, compared with a wild-type control. IC50 above this value indicates resistance. Phenotyping is not available in the UK.

Clinical application of resistance testing

Resistance testing is recommended in the following circumstances:

• At diagnosis to identify transmitted resistance.

• Before treatment initiation, including during pregnancy.

• Suboptimal virological response to treatment (<0.5 log10  in 1 month).

in 1 month).

• At each treatment failure, to guide choice of next regimen.

• If treatment is discontinued to detect mutations that may later be archived.

Management of virological failure

Definitions

• Virological failure is viral rebound >200 copies/mL or failure to achieve initial viral suppression.

• Viral rebound is failure to maintain VL below level of detection.

• Low level viraemia (LLV) is persistent VL 50-200

• Viral blip is VL 50-200, preceded and followed by undetectable VL.

• Incomplete viral response is never achieving suppressed VL after ≥24 weeks treatment.

Investigating suspected virological failure

Investigate virological failure, rebound, incomplete response or LLV:

• Check drug adherence, side effects/toxicity

• Address factors affecting drug exposure e.g. drug/food interactions, pharmacokinetics (pregnancy, co-morbidities), liver/renal disease).

• Resistance test on failing treatment or <4weeks of stopping.

• Review previous resistance tests and treatment history.

• Tropism/HLAB*57:01 test if MVC/ABC being considered.

• Change regimen as soon as viral resistance confirmed to avoid accumulation of mutations.

Treatment options following confirmed viral resistance

Treatment switch should be considered when there have been ≥2 consecutive VL >400 copies/mL, having excluded other explanations. The new regimen should be tailored according to available resistance reports and previous treatment history.

• For complex resistance seek expert advice, consult HIV MDT.

• New regimen should include ≥2 active drugs, preferably 3, to include boosted PI (ideally DRV) and ≥1 of INI, MVC, or ENF.

• First-line failure with no resistance: switch to PI/r or PI/c +2NRTI.

• First-line failure with limited resistance (NRTI+/-NNRTI): switch to new boosted PI regimen + ≥1 active drug, e.g. INI/MVC.

• Failure of first-line boosted PI+2NRTI regimen with limited PI mutations: switch to alternative boosted PI (+2NRTI), + 2 other active agents.

DO NOT

• Interrupt treatment.

• Intensify current regimen with only1 new active drug.

• Switch from boosted PI + 2NRTI to INI or NNRTI as third agent if NRTI mutations present or suspected.

Prophylaxis against infections

Here, we consider conditions in which 1° prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis should be considered. If the patient has been treated for a condition and 2° prophylaxis is being considered, refer to information for the infection in question.

Primary prophylaxis

This is where the patient is at risk of an infection and prophylactic treatment is required to prevent it.

Pneumocystis jiroveci

• Prophylaxis recommended if CD4 <200 or CD4% <14.

• First line: co-trimoxazole 480–960 mg daily (desensitization schedules are shown in Table 55.8).

• Alternative: Dapsone 50–200 mg daily plus pyrimethamine 50 mg weekly (to protect against toxoplasmosis) plus folinic acid 15 mg weekly or atovaquone 750 mg bd.

• Should be continued until CD4 >200 for 3 consecutive months.

Table 55.8 Suggested desensitization schedule for co-trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (T/S)

| Day |

Dose |

T/S |

| 1 |

1 mL of 1:20 paediatric suspension |

0.4 mg/2 mg |

| 2 |

2 mL of 1:20 paediatric suspension |

0.8 mg/4 mg |

| 3 |

4 mL of 1:20 paediatric suspension |

1.6 mg/8 mg |

| 4 |

8 mL of 1:20 paediatric suspension |

3.2 mg/16 mg |

| 5 |

1 mL of paediatric suspension |

8 mg/40 mg |

| 6 |

2 mL of paediatric suspension |

16 mg/80 mg |

| 7 |

4 mL of paediatric suspension |

32 mg/160 mg |

| 8 |

8 mL of paediatric suspension |

64 mg/320 mg |

| 9 |

1 tablet |

80 mg/400 mg |

| 10 |

1 double strength tablet |

160 mg/800 mg |

| Thereafter 1 double strength tablet 3 days a week until CD4 >200 cell/µL for at least 3 months. |

Reprinted from Absar N, Daneshvar H, Beall G. (1994) Desensitization to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in HIV-infected patients J Allergy Clin Immunol, 93, 1001–5 . © 1994 with permission from Elsevier.

Toxoplasmosis

• Recommended if CD4 <200 and positive serology.

• First line and second line: as for PCP.

• Continue until CD4 >200 consistently.

Mycobacterium avium complex

• Recommended if CD4 <50.

• First line: azithromycin 1250 mg weekly.

• Can be discontinued when CD4 >50 for 3 months.

Malaria

Should be offered if travelling to endemic area.

Penicilliosis (P. marneffei)

• If CD4 <100 consider prophylaxis with itraconazole if travelling to southeast Asia or south China where it is endemic.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

• Diptheria, Haemophilus influenza, meningococcus, pertussis.

• Contacts should be offered antibiotic prophylaxis and vaccination.

• HAV.

• Contacts should be offered HAV vaccination if HAV IgG negative if within 1 week of jaundice in index case.

• If CD4 <200 HAV-specific immunoglobulin is recommended if within 14 days of exposure.

• HBV.

• Following exposure, urgently determine HBV immunity.

• No prophylaxis required if good immunity/past infection.

• If suboptimal immunity, offer booster.

• If non-immune offer rapid vaccination course, plus HBV-specific immunoglobulin regardless of CD4 count.

Influenza

Oseltamivir or inhaled zanamivir for post-exposure within 48 and 36 hours of exposure, respectively.

Measles

Urgently request measles IgG. If measles IgG –ve and CD4 >200, measles vaccine within 3 days or HNIG within 6 days is recommended. If CD4 <200 offer NHIG regardless of measles immunity.

Polio

If immunocompromised and inadvertently given oral polio vaccine (OPV), contact with OPV recipient, or wild-type polio, give HNIG unless known to be seropositive to all 3 polio types

Varicellas zoster

Prophylaxis with chickenpox vaccine or Varivax should be given within 3-5 days of exposure. If CD4<400 varicella immunoglobulin should be given within 7–10 days of significant exposure.

Further information

British HIV Association guidelines  www.bhiva.org/guidelines

www.bhiva.org/guidelines

The Green Book: Immunization against infectious disease:  https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book

Avoid if +ve for HLA

Avoid if +ve for HLA

lipids, rash

lipids, rash