Chapter 3

The Third Reich’s world of camps

‘Certainly, anyone who had dealt with the Nazis outside a camp did not expect anything good inside one,’ writes Boris Pahor, the Slovenian former inmate of four Nazi camps. The truth of his dictum was evident from the moment the Nazis came to power. In March 1933, Stefan Lorant, the editor of the Münchner Illustrierte Presse and a Hungarian citizen, was arrested and held in prison in ‘protective custody’ for six and a half months. When he tried to understand what was happening he alighted on the notion that for millions of Germans ‘Adolf Hitler is the deliverer from “shame and disgrace”’. Lorant believed that ordinary Germans fell under a kind of spell, that the ‘time was ripe for a messiah—even a false one’. Lorant found himself one of the early victims of this messianism—those who did not fit the image of the new Germany were to be ruthlessly removed, irrespective of anything they had or had not actually done. As Lorant put it, under the terms of ‘protective custody’, ‘We have been locked up for crimes which we have not committed, but which we might commit as soon as we are free.’

Lorant’s story was, in 1933, and still in 1935 when his book was published, a brutal and shocking one, but it marked only the start of Nazi Germany’s creation of an ever-expanding extrajudicial system of exclusion and incarceration. From the prison in Munich, some of the inmates were sent to Dachau, and it was already more than clear to the men that however unpleasant their cells were, Dachau was not a place they wanted to see, since ‘Those who are incarcerated there stand only the slenderest chance of ever coming out again.’ In fact, contrary to Lorant’s perception, most early inmates of the Nazi camps were released. Lorant, shocked by being set free in September 1933 as suddenly as he had been arrested, found himself on a Munich street with daily life going on around him: ‘Calm, peace, and order reigned.’ ‘And yet,’ he wrote, ‘a few yards away, hundreds, thousands of innocent people were locked up in cells, a few yards away from the peaceful scene before me the victims of National-Socialism were torturing themselves and being tortured.’ Ten years after Lorant’s book appeared, this description of Nazi ‘protective custody’ would seem tame. Yet in the legal notion of ‘Schutzhaft’, or protective custody, is to be found the specifically German root of the Nazi concentration camps.

Lorant’s book was a bestselling book in the UK, especially when it was reprinted as a Penguin Special in 1940, but it was by no means alone. Many books described the Third Reich’s prisons and concentration camps in the 1930s in Western Europe and the US, the accounts of incarceration with titles such as Rubber Truncheon, Men Crucified, or Dachau: The Nazi Hell selling very well. Likewise, many journalistic and scholarly analyses of the Third Reich published in the 1930s and 1940s sought to explain the phenomenon of the camps, notable examples being those by Hermann Rauschning, Calvin B. Hoover, Stephen H. Roberts, F. A. Voigt, Aurel Kolnai, and Franz Neumann. As well as these condemnatory accounts, however, more sympathetic appraisals, such as Daily Mail journalist G. Ward Price’s I Know These Dictators (1937), explained that the ‘German nation’ conceived of itself as in a ‘state of siege’ and justified the ‘vigorous’ use of concentration camps as necessary in the struggle against ‘ruthless and treacherous’ adversaries. ‘Great capital,’ wrote Ward Price,

has been made by the enemies of Germany out of the concentration-camps, just as it was made by the enemies of Britain out of alleged abuses in the concentration-camps in South Africa during the Boer War. In both cases gross and reckless exaggerations were made. That there would have been far more cruelty in Germany if the Communists had been the guardians instead of the inmates of the concentration-camps is proved by the horrors that went on wherever Bolshevists have gained the upper hand.

Ward Price’s account shows how right Lorant was when he wrote that foreign visitors to Germany ‘are only allowed to see the surface of things. Which of them has any knowledge of the life in the concentration camps, in the prisons, or in the barracks of the SA?’

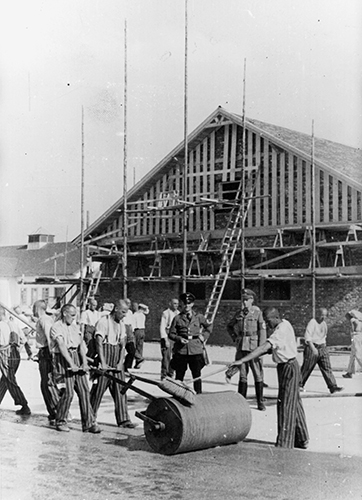

In fact, just as British or American readers could learn a good deal about the early Nazi camps, so too could Germans, for the Nazis advertised Dachau and Sachsenhausen in the press (along the lines of Figure 3) as proof of their resolve to ‘re-educate’ and ‘cleanse’ Germany. The SS journal Das Schwarze Korps, for example, ran an article on 13 February 1936 in which images of concentration camp inmates were accompanied by the following explanation: ‘This is a collection of race traitors, sexual degenerates, and common criminals who have spent the better part of their lives behind bars and other individuals who have cast themselves outside the bounds of the national community with their conduct and only three years ago were still being coddled by psychoanalysts and defense attorneys as “victims of bourgeois society”’. Just a few weeks earlier the Völkischer Beobachter argued that protective custody was a vital function of the concentration camps. ‘The main core of the inmates of the concentration camps,’ it claimed, ‘are those Communist and Marxist functionaries who, as experience shows, would immediately resume their struggle against the state if set free.’ As the camp system expanded, so the claim not to know about it became ever more implausible.

3. Inmates performing slave labour, 28 July 1938.

Early post-war accounts reveal that what had been learned in the 1930s no longer made sense, perhaps because what was discovered at Belsen, Dachau, and Buchenwald did not correspond to the earlier accounts, in which brutality was much in evidence but not terror and human destruction on an unimaginable scale. Neither shocked accounts of random violence nor apologetic explications of supposedly justifiable retribution in the first years after the Nazis came to power came close to descriptions of the camps discovered by the Allies in 1945, where filth and depravity reigned. The first post-war studies of the concentration camps such as David Rousset’s (L’univers concentrationnaire, translated as A World Apart), Eugen Kogon’s (Der SS-Staat, translated as The Theory and Practice of Hell), Bruno Bettelheim’s (The Informed Heart), and, to some extent, Hannah Arendt’s (The Origins of Totalitarianism) did not stress the ‘death camps’ in ways that we do now, but they placed an emphasis on ‘the camp’ (in French les camps became the shorthand for the whole system of Nazi rule, epitomized in Alain Resnais’s 1955 film Night and Fog), which made them stand as a synecdoche for totalitarian rule as such. ‘The camp’, though it was historically uninformed and analytically vague, was an ethical call to resist evil in the post-war world, to ‘write for the world of the living’ as Arendt put it about Rousset and Kogon.

The Nazi camps—perhaps because more was known about them than the Soviets’, but perhaps too because of the nature of the Nazis’ ambitions—gave rise to the idea that concentration camps were not just tools of pacification during warfare, as in South Africa. They represented, rather, a new form of social existence and stood as embodiments in miniature of the totalitarian systems as such. ‘From the detached point of view of descriptive sociology, a concentration camp represents a strangely unique social situation,’ wrote E. K. Bramstedt in his 1945 book Dictatorship and Political Police. Sociologists and philosophers have continued to describe the Nazi camps in such terms. Wolfgang Sofsky, for example, describes them as ‘laboratories of violence’, Maja Suderland as a ‘distorted image’ of society outside the camps. Others have sought to explain ‘values and violence in Auschwitz’ (Anna Pawełczyńska), the elimination of the ‘life-world’ in the camps (Edith Wyschogrod), moral life in the concentration camps (Tzvetan Todorov), or its opposite, ‘choiceless choice’ in the camps (Lawrence Langer). Yet in the study of the Nazi camps we are always confronted with a dilemma: there is a prosaic way of describing them, usually undertaken by historians. This involves explaining the origins and development of the camps as part of Himmler’s expanding SS, which gradually grew into a state within a state in the Third Reich; examining the operation of the camps—the guards, command structures, architecture and planning, work commandos, violence and punishment, and resistance—and showing how the camps changed over time, until they reached the massive operation of late 1944/early 1945 of main camps surrounded by many slave labour sub-camps. From this point of view, the Nazis’ vicious destruction of political enemies and their attempt to ‘clean up’ society by eliminating ‘asocials’ and other ‘undesirables’ seems historically explicable, though shocking.

On the other hand, the air of madness that surrounds the camps means that such historical or sociological approaches reach a point where their explanatory power runs out. This is where the Nazi camp system intersects with the Holocaust. Even leaving out the ‘pure’ death camps from our purview, the camps at Auschwitz—overshadowed as they were by the continual presence and threat of the gas chambers—present a bizarre phenomenon. But probably the most difficult to comprehend from the point of view of the camps’ putative purposelessness occurs at the very end of their existence: the dead mingled with the living in their tens of thousands at Belsen, the naked, emaciated survivors in Ebensee, the ‘living skeletons’ of Dachau and Buchenwald—these are the images of the Nazi camps that seared themselves into the world’s consciousness in the newsreels of 1945. Here Hannah Arendt’s point from 1950 that the concentration camps could not be understood within the frameworks of social scientific categories as they existed at that time remains fundamental: whether in law, philosophy, sociology, or history, what categories of thought, what explanatory frameworks of human behaviour can account for this phenomenon? (See Box 2.) It is hard to escape the feeling that whatever we say about the concentration camps, there is something that we just do not understand—a feeling that many survivors and commentators have also articulated: ‘know what has happened, do not forget, and at the same time never will you know’, as Maurice Blanchot wrote.

Box 2 Hannah Arendt (1906–71)

Already in 1946, Arendt had written about the Nuremberg Trial to her mentor, friend, and confidant Karl Jaspers, that the ‘Nazi crimes explode the limits of the law’. In 1950 she was making basically the same point about the concentration camps: our systems of thought lack the categories necessary to take the full measure of what the Nazis had done. In Origins of Totalitarianism (first edn. 1951), Arendt tried to provide a systematic account which combined empirical information about the camps—their origin and administration—with philosophical reflection on their meaning, arguing that the camps were a form of ‘total domination’ whose only real purpose was that of ‘making men superfluous’. Along with several other early post-war writers, Arendt therefore set the framework and terms of debate for representing the Holocaust which continue to this day.

In 1948, American journalist Isaac Rosenfeld articulated a fear that has persisted ever since:

We still don’t understand what happened to the Jews of Europe, and perhaps we never will. There have been books, magazine and newspaper articles, eyewitness accounts, letters, diaries, documents certified by the highest authorities on the life in ghettos and concentration camps, slave factories and extermination centers under the Germans. By now we know all there is to know. But it hasn’t helped; we still don’t understand.

(Preserving the Hunger, pp. 129–30)

For some, the attempt to historicize the Holocaust—by, for example, writing the history of the concentration camps in the historian’s dispassionate style—is a kind of horror: footnotes objectify and belittle the suffering of human beings. It would be arrogant to dismiss this feeling as nothing more than sentimental moralizing. Nevertheless, if we want to understand at least something of how the Nazis realized their apocalyptic dystopia then the tools of the historian must be used along with those of novelists and poets. When we go on to consider that they have continued to scar the globe since 1945, the academic study of concentration camps clearly remains doubly justified.

Let us turn then to the history of the Nazi camps. In many respects the global prehistory of the concentration camps (as outlined in Chapter 2) does not help much; as Arendt noted in a criticism of Kogon’s book, these are only ‘apparent historical precedents’. Yet Arendt’s assertion might be too easy to accept. Is there really a gulf between the Nazi system which made concentration camps the embodiment of Nazi ‘values’ and the use of concentration camps in the Boer War or in the internment of Spanish Civil War fighters in France? Are there not quite obvious continuities when one looks at the POW and civilian internment camps of the First World War, the concentration camps of German South-West Africa, and, especially, at the Armenian genocide?

The Nazi camps were initially set up on a relatively unorganized basis. The earliest ‘proper’ camps were Dachau and Oranienburg, later Sachsenhausen, camps which attracted a great deal of attention, including from the foreign press. They were places which served the purpose of ensuring that the Nazi suppression of political opposition was appreciated by the regime’s enemies, a process which worked swiftly and brutally. This is why only two of the SS’s six original concentration camps, Dachau and Lichtenburg, were in operation at the end of 1937. When Buchenwald was established in that same year, it was not, as is often assumed, because of the later predominance of communists among the prisoner functionaries, a camp for political prisoners; these had already been dealt with in the first two years of Nazi rule. Rather it was a camp primarily for ‘asocials’ and other ‘Aryans’ who refused to accommodate themselves to Nazism, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, the ‘work shy’, habitual criminals, and homosexuals. Their numbers were small: there were just 7,750 men in Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald at the end of 1937. It was the presence of such people which led to the latter camp finding its bucolic name (‘beech forest’). The logical name would have been Ettersberg, since that is where the camp is located, but as Theodor Eicke, the Inspector of Concentration Camps, wrote to Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and Chief of the German Police, in July 1937, that name ‘cannot be used’ because of the Ettersberg’s association with Goethe. Eicke’s objection was not that Goethe’s name ought not to be brought together with a concentration camp, but that his revered name should not be associated with the rejects of the Volksgemeinschaft (‘people’s community’).

The point is important because it reminds us that the SS camps were initially used for the purposes of crafting the racial community and eliminating political opponents, real and imagined. The expansion of the camp system in 1938—by the end of June 1938 there were about 24,000 inmates, mostly ‘asocials’ and other outsiders and Austrian political prisoners, in all the SS’s concentration camps—was a result of the growth in Himmler’s power and his plans to expand the SS empire. The change is signalled in the administration of the camps, which were run at first by the Inspectorate of Concentration Camps (IKL) until 1942 and then by the SS’s Business Administration Main Office (WVHA), a name which suggests Himmler’s aspirations. The camps were changing all the time in terms of their number, prominence, and make-up of the victims. But they also remained constant in their aim of terrorizing the people the Nazis named as their enemies. It is hardly surprising that one former inmate called the camps ‘schools for murder’ where bestiality was systematically trained as a logical preparation for the most merciless of wars.

This process of terror was stepped up a gear in 1938 as Jews and other groups were interned in large numbers. Before the November pogrom (9–10 November 1938, popularly remembered as ‘Kristallnacht’), Jews were among the concentration camp inmates, usually as political prisoners. As Jews they were subjected to especially rough treatment but after 1938 Jews targeted as such made up a consistently high proportion of the camps’ inmates. Just as this attack on the Jews presaged the large-scale persecution to come, so the camp system began rapidly to expand just before the start of the war. Large numbers of Czechs, veterans of the Spanish Civil War, and, especially, Poles boosted the numbers of camp inmates in 1940, which rose to 53,000, and new camps began to open, such as Auschwitz. The latter was neither originally a camp specifically for Jews nor a death camp, but was designed to hold Polish political prisoners.

The invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 brought about another expansion of the camp system, with notable camps built at Lublin (Majdanek) and Stutthof. Some 38,000 Soviet ‘commissars’ were murdered in operation 14f14 in 1941/2 and over the course of the war some three million Soviet POWs died in German captivity. In September 1942 there were about 110,000 camp inmates; this number shot up to 224,000 a year later, 524,286 a year after that, and over 700,000 by the start of 1945, as the SS desperately tried to substitute forced labour for the shortcomings of the Third Reich’s war economy. New camps, such as Mittelbau-Dora where V2 rockets were built, suddenly emerged and grew into huge, brutal factories where workers, instead of being productive in any economically meaningful sense, died in large numbers. Such huge numbers meant that far from being hidden from view, ‘concentration camps in public spaces’ became the norm and ‘the camp world invaded everyday life as never before’ (Gellately). The Buchenwald sub-camp of Magda, for example, was on the edge of Magdeburg-Rothensee, whose residents, historian Nikolaus Wachsmann reminds us, ‘looked straight into the camp, while their children played next to the electric fence’.

Once again, one needs to distinguish, at least at first, between the SS concentration camps such as Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen, and, later, Neuengamme, Ravensbrück, Mauthausen, Stutthof, and Gross-Rosen, which were designed to brutalize the inmates, and at which death was common, and the death camps—Chełmno, Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka—which were pure killing facilities, built in 1941–2, and which were not administered as part of the regular concentration camp system. The exceptions were Majdanek and Auschwitz, which by 1942 combined the functions of concentration and death camps and, especially at Auschwitz, also had massive slave labour operations attached. As well as being the primary site of the genocide of the Roma and Sinti (Gypsies), about one million Jews were murdered in the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Transit camps and labour camps associated with the administration of the Holocaust were also established, such as Herzogenbusch in the Netherlands. The difference between all these sorts of camps was not very widely understood during the war. This lack of clarity, combined with the chaos of the end of the war which brought the different camps crashing together, contributed to the confusion about the geography and operation of the Holocaust for years after the war’s end. With the exception of Auschwitz and Majdanek, it was only late in the war that the systematic murder of Europe’s Jews became entangled with the wider history of the concentration camps.

For the inmates, life in the concentration camps was brutal and is often depicted in crude Darwinian terms as a struggle for survival. Although there are many recorded instances of assistance and mutual aid amongst inmates in the camps, survival required more than luck. ‘In the camps,’ wrote Joop Zwart, a prominent Dutch political prisoner in Belsen in a testimony of 1958, ‘the conditions there could not be measured with the moral standards of a free society.’ This individualistic disregard for others might have enabled some to survive, but it also hindered the survival of the many, and there are, contrary to Zwart’s claims, many instances of survivors testifying to the importance of being part of a pair, small group, or ‘substitute family’. Zwart claimed that

Nobody could afford to help first somebody else with a thing he himself needed most. Still, with more solidarity among the prisoners it is my conviction that many more thousands could have been saved. But it seemed as if the people in the camps did their very best to shed their best qualities as quickly as possible for their very worst qualities. So not only envy, but betrayal and worse, reigned.

This harsh judgement certainly tells us something about how the camps functioned, though Zwart omitted to mention that these conditions were not those of the inmates’ own making. If they did not live up to the standards of decent behaviour, we might remember that this was one of the consequences of the camps the Nazis intended.

One of the main confusions in our understanding of the Nazi camps concerns the role played by work. The term ‘annihilation through labour’ (Vernichtung durch Arbeit) is widely understood to refer to a deliberately conceived Nazi policy. In fact, concentration camp inmates had been used for forced labour from the camps’ early days. Later in the war, when foreign forced and volunteer labourers (of whom there were already some twelve million in Germany) proved insufficient, concentration camp labour was used more readily because of the shortages in manpower from which the German economy was suffering. It was at this point—autumn 1944—that large numbers of sub-camps appeared. Gross-Rosen, for example, had over a hundred sub-camps by the end of 1944 and, with nearly 77,000 inmates, held some 11 per cent of the total concentration camp population.

Where concentration camp inmates—as opposed to forced labourers—were forced to work, this was only ever a temporary measure designed to extract as much value as possible out of inmates before their deaths. Particularly for Jews, work was only meant as a brief interlude, a necessary evil. It was, as historian Marc Buggeln says, ‘a measure of last resort for a mercilessly overheated armaments industry and in a system whose downfall was ever more likely in view of the hopeless state of the war’. When some SS managers attempted to ‘modernize’ their enterprises, they nevertheless took it for granted that the lives of their workers would be short and they rarely made any efforts to increase productivity by improving living conditions or food quantity. Still, memoirs of inmates of the Gross-Rosen or Neuengamme sub-camps, for example, report that conditions were far preferable to those at Auschwitz, from where many of them had been deported. Vĕra Hájková-Duxová, for example, says that in arriving at Christianstadt, a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen, from Auschwitz in autumn 1944, the women ‘couldn’t get over their amazement’ when they saw proper bunks with straw mattresses. The collapse of the Third Reich in the spring of 1945 thus meant that Jewish camp inmates who were being used as slave labourers were actually (on average) in somewhat better health than those who were not. Certainly they would have died if the war had lasted longer, but ironically it was slave labour which actually prolonged the lives of many until the point at which they outlived the regime—although there are striking differences between survival rates at some sub-camps in comparison with others, as for example in the sub-camps of Neuengamme, where much depended on whether one worked inside or outdoors, or on the guards’ levels of brutality. But many of these workers—Jews and non-Jews alike—were not liberated where they worked, for they had been forced to march elsewhere in the Third Reich’s dying days.

The last months of the war are the most important for understanding how the state of the camps at liberation has so impacted on the world’s understanding of what a concentration camp is. With the Reich collapsing, huge numbers of camp inmates were forcibly evacuated from the camps that were under imminent threat of discovery by the Allies, especially by the Red Army, and sent into the heart of Germany on what the victims named ‘death marches’, a name that has subsequently become common currency since it so accurately captures the absurd viciousness of the process, and identifies the marches as part of the Holocaust. That means that the camps still in existence in early 1945 were heavily overburdened with vast numbers of already ill and dying inmates, in conditions of chaos where caring for concentration camp prisoners was low on the list of priorities for the Third Reich’s administrators. Dachau in April 1945, claims historian Barbara Distel, could no longer be distinguished from the other sites of mass murder. Belsen, a camp that had been opened in 1943 as a holding camp for ‘privileged’ inmates (ones whom the Reich thought could be useful in negotiating with the Allies), was functioning like a death camp because huge numbers were dying there every day from lack of food and water: in March 1945 alone, 18,000 inmates died. The camp system as such was imploding along with the SS bureaucracy in general, and the individual camps were disaster zones at which immense human suffering became the norm. If there was a collapse in the distinction between the murder of the Jews and the concentration camps, it lay in the fact that the majority of Jews liberated at Dachau, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, and Bergen-Belsen were survivors of the camps further to the east—including many Jewish slave labourers who had been in small sub-camps—who had been marched westwards in the face of the Soviet advance.

The Nazi concentration camp system was vast and, as the Nazi empire expanded, so too did its camp network, so that it covered the whole of occupied and Axis Europe. Alongside the SS camps there were camps for POWs (including Stalags or main POW camps and Dulags or transit camps); camps for so-called Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) who were supposed to be ‘resettled’ in farms vacated by Poles; and forced labour camps, for example for Polish Jews in the area of occupied Poland the Nazis called the Generalgouvernement, or for Ostarbeiter (workers from the east) who were held in huge numbers in the Reich in terrible conditions. Such camps existed in almost every locale in Germany. The Nazis’ allies also set up camps of their own, sometimes genocidal camps in their own right—as in Jasenovac in Croatia—and sometimes waystations to genocide. In Transnistria, the area of western Ukraine between the Dniester and Bug rivers occupied by the Romanians, a combination of ramshackle camps and more or less open-air dumping grounds for local and deported Jews and Roma caused immense loss of life in the first two years of the war, including the massacre of almost 48,000 Jews at Bogdanovka in December 1941.

Yet the Third Reich was a world of camps in another respect too. Just as the regime’s de facto ‘enemies’ were eliminated through the use of concentration camps, so the Volksgemeinschaft, the ‘people’s community’, was to be brought into existence and trained in martial values through the use of a variety of labour camps (Reichsarbeitsdienstlager) for different constituencies: Hitler Youth, BDM (Bund Deutscher Mädel or League of German Girls), and teachers, for example. Indeed, according to a law of November 1934, the term Arbeitslager (labour camp) was reserved for organizations which catered for Volksgenossen (racial comrades) and which were devoted to the honour of the German Volk. Camps therefore became a necessary fixture of German life, whether for those excluded from the racial community or for those who were to be drilled into it. The Labour Service camps in particular became must-see sites for foreign dignitaries and tourists alike and were regarded by Nazi commentators as ‘the best means of making this National Socialist call for a Volksgemeinschaft a reality’, as Reich Labour Leader Konstantin Hierl put it (cited in Patel).

The anti-Nazi lawyer Sebastian Haffner experienced such a camp himself when he was ordered to attend it for ‘ideological training’ just before taking his assessor examination in October 1933. Finding the camp and the SA men who ran it ridiculous but also threatening, Haffner and his fellow articled clerks went unenthusiastically along with what was expected of them—singing, marching, ideological instruction sessions—until he had to admit that by doing so, no matter how reluctantly, the effect was undeniable: ‘By acceding to the rules of the game that was being played with us, we automatically changed, not quite into Nazis, but certainly into usable Nazi material.’ Asking himself why they did go along with it, Haffner honestly admits several reasons: attending the camp had become a requirement for passing the law exams; the attendees mistrusted one another, being unable to fathom each other’s real attitude towards the Nazis; and finally a ‘typically German aspiration’—the ‘idolization of proficiency for its own sake, the desire to do whatever you are assigned to do as well as it can possibly be done.’ Besides, once the inmates were offered some proper military training, they even began to enjoy it, despite themselves. ‘Thus,’ Haffner writes, ‘we believed we had escaped ideological training, even while we were thoroughly immersed in it.’ Even more pernicious, Haffner explains that after a period in the camp, the individual began to lose a sense of himself as significant, with all thought and action in the camp being channelled in favour of the group. Waking in the night, Haffner felt ashamed to be wearing a uniform with a swastika armband—but he wore it nonetheless. He was ‘in the trap of comradeship’.

Indeed, the trap of comradeship was exactly what the Nazis aimed for. It constituted the counter-image of the ‘comradeship’ created in the concentration camps. Where the rejected would be isolated from the rest of the society, the latter would be frogmarched into the Volksgemeinschaft. A society modelled on the barracks, everyday life as camp, is what the Nazis aimed at. And many celebrated it. Melita Maschmann, for example, author of a memoir of growing up in Nazi Germany, claimed that:

Our camp community was a miniature model of what I imagined the racial community [Volksgemeinschaft] to be. It was a completely successful model. I have never before or after experienced so good a community, not even in places which were more homogeneous in every respect. Amongst us women there were farmers, students, workers, shop assistants, hairdressers, school pupils, office workers and so on. The camp was led by an East Prussian farmer’s daughter who had never before been outside of her own home region [Heimat] … Experiencing this model of the Volksgemeinschaft with such an intensive feeling of happiness produced in me an optimism which I stubbornly clung on to until 1945.

(Cited in Wildt, ‘Funktionswandel’, p. 80)

By contrast, even though many disliked it, like Haffner the great majority went along with it because they were afraid of the other sort of camps that awaited them if they objected. Haffner knew, when he was writing in 1939, that this variety of comradeship—the forced creation of community—could become ‘the means for the most terrible dehumanization’; and he argued ‘that it has become just that in the hands of the Nazis. They have drowned the Germans, who thirst after it, in this alcohol to the point of delirium tremens. They have made all Germans everywhere into comrades’, and comradeship, Haffner pointed out, ‘is part of war’. These thoughts on the use of camps for the creation of the Volksgemeinschaft have been confirmed by scholars, who show that there was a dialectical relationship between belonging and genocide. When Haffner wrote in 1939 that ‘The general promiscuous comradeship to which the Nazis have seduced the Germans has debased this nation as nothing else could’, he could not have known of the Holocaust or of the full extent of Nazi criminality more generally. But he sensed that that there was a connection between the camps for the racial comrades and the camps for the social, political, and racial rejects. The Janus-faced nature of the Nazi camps meant that a concentration camp for the eradication of enemies required few alterations to become instead a site for the education of the racially valuable members of the Volk. Inclusion and exclusion went hand in hand; the former required the latter, and vice versa.

Of course it is the ‘exclusion’ side of the equation for which the Third Reich’s concentration camps are remembered. When the British army encountered Bergen-Belsen it was unprepared for ‘the world of nightmare’ which it found there, as Richard Dimbleby put it in his radio despatch of 17 April 1945. Entering the camp was shocking enough, with corpses littering the site and the barely alive staggering about. But nothing prepared Dimbleby for what followed:

I have seen many terrible sights in the last five years, but nothing, nothing approaching the dreadful interior of this hut in Belsen. The dead and the dying lay close together … They were crawling with lice and smeared with filth. They’d had no food for days, for the Germans sent it down into the camp en bloc and only those strong enough to come out of the huts could get it. The rest of them lay in the shadows getting weaker and weaker. There was no one to take the bodies away when they died and I had to look hard to see who was alive and who was dead.

(Despatch reprinted in Bloxham and Flanagan (eds), Remembering Belsen, p. xii)

Similarly, American journalist Percy Knauth described Buchenwald on its liberation, saying that ‘Until that moment, I had never fully realized what a concentration camp like Buchenwald was.’ Now he felt that ‘it did not seem possible that anyone who ever saw the terrible misery of Buchenwald, let alone had lived in it, would ever be able to forget it and go back to normal human living.’ The scenes described by Dimbleby, Knauth, and many others in Germany in 1945 have defined how we think about concentration camps.

For many historians today, the extraordinary vileness of the Nazi camps means that it is invalid to use the term ‘concentration camps’ to encompass both the Nazi sites and those established by regimes in other times and places. Yet many of the first people to see the Nazi camps in 1945 made the connection explicitly, as a way of warning the world of the risk of seeing the Third Reich as a sui generis case. Knauth, for example, not only admonished his fellow Americans for failing to do anything about the Nazi camps whilst they were in existence, he went further and urged his readers to think through what the Nazi camps meant for humanity:

And even in this year of peace and victory, we have let the concentration camp live on. We have let it live in Argentina, right in our own hemisphere. We have let it live in Egypt, where Greek soldiers who a year and a half ago revolted against a government-in-exile which had oppressed them while it held the power were clapped in prison by our British allies. We are letting it live in country after country—in Greece and in Palestine, in India and in Spain, among nations liberated and unliberated from the oppressions against which, after four long years, we were finally forced to fight. We wrote ‘Four Freedoms’ on our banners—freedoms for which men were dying in places we had never heard of; but now the freedoms and the places and the Buchenwalds have all receded into the unpleasant past … Our measure of responsibility for Buchenwald is not so great or immediate as is Germany’s, but it is equal with Germany’s responsibility for concentration camps as a creation of mankind. If we deny that responsibility today, as Germany did when Hitler came to power, we may find Buchenwald in our own land tomorrow.

(Germany in Defeat, pp. 62–3)

This kind of universalizing moralizing is not to everyone’s taste. Some may find Knauth’s argument that all people are to some extent responsible for things done by a certain regime unpalatable, regarding it as playing down the specific responsibility of those who created and ran the camps. Yet there are different ways we can read Knauth. He could be warning us not to regard the Nazi camps as the only manifestation of concentration camps in history. He may be reminding us that even if they are not as destructive or as synonymous with a ruling ideology as the Nazi camps, concentration camps can still exist elsewhere. And he might be telling us that bracketing off the Nazi experience—even if done for valid and justifiable reasons—might have the opposite effect to the one intended and might allow inhumanity to flourish. Indeed, it is quite clear that the camps we have encountered thus far in this book, in Cuba, the Philippines, South Africa, German South-West Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and the Third Reich, are all quite different. That it is nevertheless possible to speak of them using the same designation—concentration camps—does not mean that they are the same either empirically or morally. The existence of Dachau should not prevent us from recognizing concentration camps elsewhere. That is perhaps nowhere more clear than in the history of the Gulag, which we will examine next.