Chapter 5

The wide world of camps

A percentage of the continent’s population had become quite accustomed to the thought that they were outcasts. They could be divided into two main categories: people doomed by biological accident of their race and people doomed for their metaphysical creed or rational conviction regarding the best way to organise human welfare.

As Arthur Koestler’s words from his novel Scum of the Earth (1941) make plain, the Third Reich’s and Soviet Union’s camps were not the only ones to exist before and during the Second World War. Japanese camps for Allied soldiers and civilians during the Pacific War, the Croatian camp at Jasenovac, the French internment camps in the south of France, Italy’s island and African camps, and the Romanian occupation of Transnistria, which essentially became a giant, open-air concentration camp, all suggest that the Nazis’ allies were willing users of camps, some more brutal and destructive than others. The democratic countries have also been accused of making use of concentration camps; the charge might have some validity, although here we can see degrees of difference between the Nazi/Soviet camps and the British/American. In the case of the British, one sometimes hears that internment camps for ‘enemy aliens’ or, after the war, the use of internment camps on Cyprus to hold Jewish DPs—Holocaust survivors making the ‘illegal’ journey to Palestine—were concentration camps. In the American case, the wartime decision to intern American citizens of Japanese descent is often discussed using this vocabulary, with books with titles such as Concentration Camps USA being quite common. Were these institutions concentration camps?

After the war, concentration camps rapidly came to appear synonymous with the Third Reich. Yet as we have seen, concentration camps were by no means the invention of the Nazis, nor—if we exclude the death camps—were the Nazis’ camps necessarily more deadly or brutal than those of other regimes. The Third Reich’s characteristics as a whole—Nazism as a political ideology, the ‘racial community’ as an aspiration, the dreams of a German-dominated, racially reordered European empire—were the factors that made Nazism so apocalyptically destructive: the inseparability of word and deed in Nazism. Although the camp system was central to the Nazis’ plans, especially for the creation of a helot population of Slavs who would serve their racial masters, when we consider them purely as institutions in their own right it is hard to say that the Nazi concentration camps were very different from those elsewhere. In fact, we can see that the Nazi camps provided the inspiration for camps in other countries after 1945, as in Argentina and Chile, or communist prison camps such as Piteşti in Romania. Some of the Nazi camps even continued to be used as camps for political prisoners, what the Soviets in their occupation zone of Germany called ‘special camps’.

It is unsurprising, then, that shortly after the war the continued existence of camps in the world was a cause of grave concern to certain groups of intellectuals. In 1950, for example, the newly founded Commission internationale contre le régime concentrationnaire (CICRC) undertook investigations into camps in post-Civil War Spain. It was supported in the endeavour by the Buchenwald survivor and (at least in France) well-known author David Rousset. Rousset had coined the term L’Univers concentrationnaire in his book of that title in 1946 and now, as a co-founder of the Rassemblement démocratique révolutionnaire, an anti-Stalinist party of the left, he was keen to rebut accusations from communists that the CICRC’s focus was only on the Soviet Union, as it had been in its first inquiry. It would also go on to investigate the use of camps in Greece, China, Tunisia, and Algeria.

Taking the Nazi camps as its point of departure—because here ‘each of its characteristics were pushed to the extreme’—the CICRC set out that its aim was to determine

if there exists or not, in the countries under consideration, a concentrationary regime or concentrationary characteristics, such a regime being defined by the arbitrary deprivation of liberty, inhumane detention conditions, the exploitation of detainees’ labour for the benefit of the state.

The CICRC was aware of the double risk: that one might consider acceptable anything which didn’t reach the degree of severity of the Nazi camps on the one hand or that one might decide to call a ‘concentration camp’ anything which one might find unacceptable on the other. Those problems have dogged comparative studies of concentration camps and fascist or totalitarian societies ever since.

That is hardly surprising when one considers the numerous different sorts of camp settings that have existed since the war: internment camps, refugee camps, detention centres, and so on. In examining some of them now, I want to keep open the question as to whether they should all be called concentration camps. Most will probably agree that the term is not applicable in some cases. Yet all the examples I discuss below are of camps where civilians were held against their will—to a greater or lesser extent.

Italy, France, and Spain

In Italy islands such as Lipari, Pantelleria, and Lampedusa south of Sicily and two of the Tremiti Islands in the southern Adriatic were used to confine political enemies. The practice of internal exile for political outcasts had existed in Italy since the 19th century but was expanded under Mussolini. Whilst the Fascist regime made much of the comfort in which a few former parliamentarians lived in their island prisons, especially on Lipari, the reality for most political detainees was quite different. These colonies, in which political detainees often lived alongside common criminals, ‘soon came to resemble true internment camps, with most detainees living in common barracks’, as historian Michael Ebner puts it. When the regime also started expelling the ‘least dangerous’ detainees to villages in the south after 1935 and then started to use the labour of detainees for land reclamation projects, it was presiding over what Ebner calls a ‘Fascist archipelago’ which formed just part of the regime’s way of imposing its discipline on the Italian population. Within it, the tiny islands of Ventotene and San Nicola were especially well suited to confinement, with few natural resources and high cliffs. The latter, says Ebner, ‘resembled a true concentration camp’, since there was nothing there but a castle whose row houses served as barracks. Furthermore, the detainees were subjected to continual surveillance and controls on their ability to meet or move about freely. They were not held in these places in order to die, but ‘the experience killed many of them and left many others gravely and chronically ill’.

But Italian camps were not found only on small islands off the coast of Italy; nor were they used solely to confine Italian political enemies. The historian Luigi Reale says that fifty-two ‘fascist concentration camps’, holding about 10,000 civilians, were set up all over Italy between 1940 and 1943, ‘directly influenced by Mussolini’s race laws that he introduced in 1938’—that is, primarily for Jews and Gypsies, but also foreign citizens. These were often buildings such as castles, former convents, or prisons that were adapted for use as camps, although at Marconia (Pisticci) and Ferramonti (Tarsia), the latter of which was established to hold Italian and non-Italian Jews, there were purpose-built camps surrounded by barbed wire. Internment in these camps was often deadly, as Tone Ferenc, a Slovenian eye-witness, reported:

The camp was surrounded by barbed wire, but there was a small passage through to get to the administration that was in the school on top of the hill. Down below I saw a huge crowd of women and children. Cries would go up to curdle the blood. The little ones used to cry. They were half naked, with emaciated faces and their bellies distended from hunger; their eyes were glazed over in desperation because of their privations. Men would be sitting on the ground, dropping from fatigue. They would try to pick the fleas off themselves.

(cited in Reale, Mussolini’s Concentration Camps, p. 114)

The most notorious Italian camp was the Risiera (rice-processing factory) di San Sabba, near Trieste, where some 5,000 were killed in Italy’s only death camp, and a further 20,000 were deported to Auschwitz and other Nazi camps. It was established during the violent last stage of the war as the main camp in the German-designated region of Adriatisches Küstenland (Adriatic Coast).

Italian camps were not found solely in Italy itself; in Albania, Somalia, Libya, and Slovenia, the Italians also set up camps. Between 1930 and 1933, some 40,000 camp inmates died from hunger, illness, and overwork. There are even indications of an attempt to create in 1932 an ‘extermination camp’ for Italian political prisoners in the Libyan Sahara, in Gasr Bu Hadi, 478 km south-east of Tripoli. In the end financial constraints meant it was not built but the idea shows the logic of fascism’s radical exclusion taken to its extreme.

This logic is visible in the French camps set up to house exiles from Spain and the Francoist camps created during and after the Civil War. Republican exiles who had been interned in France had already experienced what would later become hallmarks of the fascist camps: brutal treatment behind barbed wire, exposure to the elements, the torment of being so close to people outside living normal lives. Some of these camps, especially the beach internment camps of Argelès, St Cyprien, and Le Barcarès, were built at short notice to house refugees. Others, like Le Vernet, where Koestler was interned, or Gurs, where Hannah Arendt was held, were consciously established by the French authorities as punishment camps. From them, the French deported—to almost certain death—several thousand to Gestapo control or to brutal work camps in North Africa (see Figure 6). Koestler is quick to point out that Le Vernet was not Dachau:

In Liberal-Centigrade, Vernet was the zero-point of infamy; measured in Dachau-Fahrenheit it was still 32 degrees above zero. In Vernet beating-up was a daily occurrence; in Dachau it was prolonged until death ensued. In Vernet people were killed for lack of medical attention; in Dachau they were killed on purpose. In Vernet half of the prisoners had to sleep without blankets in 20 degrees of frost; in Dachau they were put in irons and exposed to the frost.

(Scum of the Earth, p. 94)

6. ‘What about Us, Mr Macmillan?’, David Low cartoon, Evening Standard, 26 February 1943.

Yet as historian Helen Graham notes, ‘in the very possibility of comparison, Koestler reminds us that here in the network of internment and “punishment camps” for brigaders and refugees that covered the landscape of Roussillon in “peace time”, the European concentration camp universe was already in existence’. Those held in Le Vernet, Gurs, or one of the other small French camps were ‘excluded from all “nations” and thus devoid of both the symbolic value and rights such membership afforded’.

The camps in Spain were entirely premised on the need for discipline and punishment; Franco’s carceral universe was co-extensive with Spain. Following his victory in the Civil War, Franco set out to ensure that those he deemed the ‘anti-Spain’ would be punished for their support for the Republic. At least 60,000 people—the figure is the regime’s own—were held without any judicial involvement in 1940 alone. A vast expansion of the prison universe took place so that buildings from schools to warehouses were pressed into service; at the same time, ‘a constellation of labour battalions, work brigades and other instruments of slave labour such as military penal colonies’ stretched across Spain. Violence, as the leading historian of the Spanish camps, Javier Rodrigo, notes, was ‘the rock upon which the Franco regime was built’. The CICRC noted in its 1953 report that, as in a concentration camp regime, ‘inmates suffered dire material conditions and extreme forms of arbitrary violence that frequently led to their deaths’. They were also subjected to forced labour, whether still imprisoned or whether ‘released’ in order to join labour battalions or under the scheme known chillingly as ‘Punishment Redemption through Work’ (Redención de Penas por el Trabajo), battalions ‘that depended directly on the concentration camp structure’.

According to Rodrigo, more than half a million Spaniards and other Europeans passed through the more than 180 camps which made up the Francoist concentration camp system. The largest, Miranda de Ebro, opened in November 1936 and remained in existence until 1947 (others lasted considerably longer). As of June 1937, they were administered by the Prisoner Concentration Camps Inspectorate (Inspección de Campos de Concentración), which, as Rodrigo notes, ‘is eerily reminiscent of Eicke’s Nazi Inspectorate of 1934’. Indeed, in 1940 Himmler inspected Franco’s camps and prisons and Spanish officials visited Sachsenhausen. Yet until recently Franco’s camp system had been largely forgotten, perhaps because it was not exposed and defeated in war, meaning that the regime’s longevity allowed it to align itself with the Cold War West. The irony, as Helen Graham notes, is that ‘a Western order that retrospectively mythologized its opposition to Nazism as opposition to the camp universe, and which denounced this too as the ultimate offence of Stalinism, patronized a regime in Spain that was, like the Soviet Union’s, based on mass murder and its own gulag’.

Liberal internment

By comparison with the Italian or Spanish examples, which followed the radicalizing logic of fascism, the internment of civilians by the liberal democracies was quite different. Yet the American decision to intern Japanese Americans and the British decision to intern German Jewish ‘enemy aliens’ have received considerable criticism, not least because their sites of internment are often described as concentration camps.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans came under suspicion. In the anti-Japanese clamour, this statement from leading anti-Japanese campaigner Lieutenant-Colonel John L. De Witt was typical:

I have little confidence that the enemy aliens are law-abiding or loyal in any sense of the word. Some of them yes; many, no, particularly the Japanese. I have no confidence in their loyalty whatsoever. I am speaking now of the native born Japanese—117,000—and 42,000 in California alone.

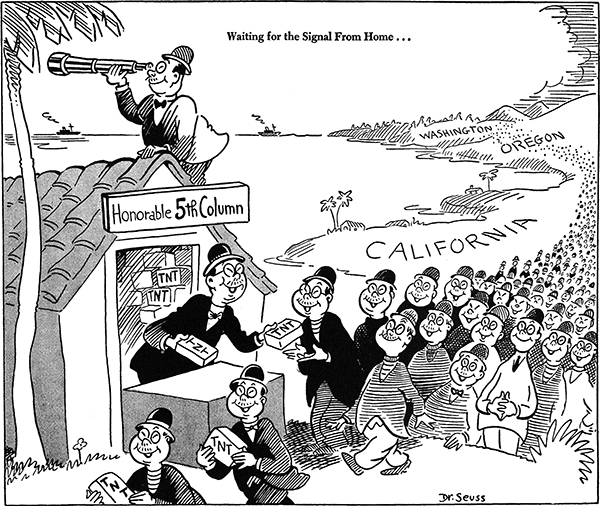

Ultimately it was President Roosevelt’s decision to intern the Japanese, one he took on the basis of his own personal antipathy and because anti-Japanese feeling was generally strong—historian Roger Daniels puts it down to ‘the general racist character of American society’, as illustrated in the Dr Seuss cartoon (see Figure 7). Indeed, the decision to intern the Japanese Americans was made before Pearl Harbor.

7. ‘Waiting for the Signal from Home’, Dr Seuss cartoon, PM, 13 February 1942.

In May 1942 Miné Okubo and her brother were incarcerated, along with thousands of others, in Tanforan Assembly Center, a race track in San Bruno near San Francisco. A young woman who had studied in Europe, Okubo produced a record of her internment which combines comic-style line drawings with wry comments. She records, for example, that letters from friends in Europe ‘told me how lucky I was to be free and safe at home’. The camp was still being built when she arrived and Okubo’s description of the barracks, the latrines, and wash halls seems familiar to us from descriptions of earlier camps:

We were close to freedom and yet far from it. The San Bruno streetcar line bordered on the camp on the east and the main state highway on the south. Streams of cars passed by all day. Guard towers and barbed wire surrounded the entire center. Guards were on duty day and night.

Yet the presence of a post office, laundry buildings, a library, and schools, and the fact that internees could receive guests, clearly indicate that Tanforan was no Dachau. Nevertheless, the Japanese Americans were being held against their will without having committed a crime, and were being kept under watch in guarded, fenced-in camps. This fact leaves some historians, such as Tetsuden Kashima, in no doubt as to what to call them:

The most accurate overall descriptive term is concentration camp—that is, a barbed-wire enclosure where people are interned or incarcerated under armed guard. Some readers might object to the use of this term, believing that it more properly applies to the Nazi camps of World War II. Those European camps were more than just places of confinement, however; many were established to provide slave labor for the Nazi regime or to conduct mass executions. I contend that such camps are more properly called Nazi slave camps or Nazi death camps.

(Judgment without Trial, p. 8)

Even if one rejects the claim that Tanforan, Minidoka, Manzanar, and the other incarceration sites should be described as concentration camps, calling them ‘internment camps’ or ‘assembly centres’ should not make us think that the experience was somehow pleasant or that the decision to intern Japanese Americans was a credit to a democratic state. All that really happened was that, as Roger Daniels puts it, ‘The myth of military necessity was used as a fig leaf for a particular variant of American racism.’ Indeed, the practice set a precedent for post-war America: at the height of the Cold War the Emergency Detention Act (1950) gave the president the right to set up camps for ‘The detention of persons who there is reasonable grounds to believe will commit or conspire to commit espionage or sabotage’ (Sec. 101 [14]). Daniels observed in 1971 that ‘Any foreseeable use of these concentration camps will be for ideological rather than racial enemies of the republic.’ Although the act was partially repealed by the 1971 Non-Detention Act, Daniels here presciently foresaw Guantánamo Bay.

The internment of Japanese Americans was by no means the only example of a supposedly democratic country succumbing to fears of enemies within and incarcerating innocent people. The Americans interned Germans too. In Britain, German and Austrian Jews and Italians were absurdly targeted at the outbreak of war as a potential fifth column—as good an illustration of the power of populist paranoia as any in history. The result was that some 27,000 were interned, in a number of sites including Seaton in Devon or at Huyton near Liverpool, but the majority on the Isle of Man, where civilians had been interned during the First World War too. Several thousand of them were deported to Canada. As François Lafitte, author of a still relevant, powerful study of the policy reflected, internment was the result of panic and prejudice among government ministers and unchecked rumour-mongering by the popular press. Lafitte also observed that

Both in the Press and in public speeches certain gentlemen whose pro-Nazi views were notorious in peacetime were among the loudest in the clamour to ‘intern the lot’. Protestations of super-patriotism in this cheap and easy form have often been the rather obvious defence-mechanism resorted to by men about whose patriotism there was some doubt.

The policy was stupid and cruel, and the conditions in which the internees lived were hardly pleasant. Yet in this case one cannot speak of a concentration camp; the exiles’ self-designation as ‘His Majesty’s Most Loyal Enemy Aliens’ hardly suggests people who were at bitter odds with their captors. Indeed, one internee wrote that

the most interesting point in the internment problem is not how much the interned have had to suffer—for suffering is general all over the world at present—but how far they have been able to stand up, spiritually, to their trial, and to transform their adversities into productive experience (cited in Seyfert).

Nevertheless, even if one cannot speak of British concentration camps, it was the case, as Lafitte pointed out, that internment represented ‘an authoritarian trend … in our home life’, suggesting that the spread of illiberal ideas concerning foreigners, citizenship, and national belonging was very hard for the democracies to resist when the fascist countries seemed to be in the ascendant.

The ambiguity of liberal incarceration was particularly apparent in the DP camps that were set up in Germany and Austria after the war. Immediately on war’s end there were some seven million DPs in occupied Germany; by September 1945 in a remarkable feat of logistics given the war-torn state of Central Europe, some six million of them had been helped to return to their homes. The last million were the so-called ‘hard-core’ cases, mostly Poles and Ukrainians—some with questionable wartime records—who refused to return to countries being taken over by communist regimes. There was also a contingent of approximately 100,000 Eastern European Jews, survivors of the Holocaust, who had no homes to go back to, whose communities no longer existed, whose families had been murdered, and whose property had been stolen. In 1946 they were joined by Jews, including complete family units, returning to Europe after spending the war in exile in the Soviet Union, mostly in Central Asia. Many thousands had lost their lives there but this exile also facilitated the survival of tens of thousands of Jews who would surely have been murdered by the Nazis had they remained in situ and not fled or been deported by the Soviets in 1940–1. So by the end of 1946, there were some 250,000 Jewish DPs in camps in Germany and, to a much lesser extent, in Austria and Italy.

These camps were there because the Jewish DPs, assuming that after the war their suffering would elicit support from those who had liberated them, demanded access to the US and Palestine. These, unfortunately, were the two places to which they were least likely to be granted access. Many survivors found their way to Britain, Australia, and Latin America, but to Palestine only in large numbers after the Israeli declaration of independence in May 1948 (the brichah scheme for illegal immigration had helped many already) and to the US after the amendment of the DP Act in 1950, when the numbers were much reduced in any case. In the years in between, the relations between the DPs and the British and American authorities soured, and the DPs themselves made great play of the fact that they were being held in an Allied version of Nazi concentration camps. This made for powerful Zionist propaganda and gave the Soviets the opportunity to attack British imperialism in the context of the emerging Cold War. The problem was exacerbated by American criticism of the camps; Earl Harrison, in his summer 1945 report on the DP camps, wrote that ‘we appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them except that we do not exterminate them’. The Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine concurred in spring 1946 and restated Harrison’s demand that 100,000 Jewish DPs should be immediately permitted to enter Palestine. In the meantime children marched in the DP camps—such as Zeilsheim or Belsen—demanding the free world to recognize their continued ‘imprisonment’, and anti-British campaigners used slogans such as ‘British floating Dachau’ to describe brichah ships seized by the British or chanted ‘Down with Bevin, the successor to Hitler.’

Even more than the DP camps in Germany, which at least could justifiably be represented as emergency housing for desperate people, the British camps on Cyprus for illegal immigrants to Palestine were open to the charge of being ‘concentration camps’. For here, the Jews who arrived were not simply being housed where they had been liberated or where they had found themselves after discovering the loss of their homes; they were rather being intercepted and prevented from exercising their will. The result was disastrous for Britain’s moral standing in the world. ‘Standing on this sun-baked forlorn island,’ wrote Ira Hirschmann, the personal representative of Fiorello La Guardia, head of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), whilst waiting for a plane in Cyprus in May 1946,

how could one imagine, even in his most sinister dreams, that within the next few months it would become the prison of more than 30,000 Jewish refugees, seized by His Majesty’s Royal Navy, taken from tiny, leaking ships bound for Palestine, and that the British government would so soon take over Hitler’s role as keeper of the concentration camps, and immortalize Cyprus along with names like Dachau, Belsen and Maidanek?

Such statements were hyperbolic, designed to achieve a political goal; but even if no one was being tortured or starved to death in the Cyprus DP camps, their presence so close to Palestine indicated British weakness rather than strength. It seemed as if it were only a matter of time before the British would yield to the DPs’ demands and the clear continuity in the DPs’ experience of incarceration was deeply embarrassing for the British, who were rightly celebrated as having helped to save many thousands of survivors in the preceding years.

The post-war DP camps were not concentration camps because those in them were not without legal or other forms of representation. Had they not been holding out to go to particular places, the non-Jews could have returned ‘home’ any time they liked—although for those going back to places like Ukraine or the Baltic States, which were being incorporated into the Soviet Union, this was tantamount to suicide. The Jews were more at the will of the authorities since they had nowhere to return to. Yet once again it is the imagery of camps that is so shocking rather than the actual continuity in experience that mattered—the British- and American-run DP camps were very far from being concentration camps in the sense that is usually understood: they were thriving communities with schools, kindergartens, presses, religious institutions, vocational training schools, sporting associations, and political movements. Even so, the people in them wanted nothing more than to leave for somewhere of their own choosing. The camps in Cyprus have a greater claim to be called concentration camps, not least because the colonial setting suggests a kind of population management that echoes previous episodes. Yet again, the camps themselves functioned like enclosed societies—though there were contacts with the local population too—and although the fact of being held in camps made for good propaganda, the DPs’ claims that they were being held in the British version of Dachau does not stand up to scrutiny.

These fundamental distinctions between Nazi camps and DP camps cannot be applied in the case of the ‘special camps’ in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. Following long-term Allied plans as definitively set out in the Potsdam Agreement of 2 August 1945, the Soviets (like the British and Americans) arrested and interned Nazi functionaries in ten ‘special camps’ at the end of the war. These camps remained in existence until 1950; among them were Sachsenhausen (Special Camp No. 2) and Buchenwald (Special Camp No. 7), the latter of which, though liberated by the Americans, fell into the Soviets’ occupation zone and was therefore administered by the Soviets as of August 1945. According to figures released by the Soviets to the GDR’s CDU interior minister, Peter-Michael Diestel, in 1990, there were 122,671 Germans imprisoned in the special camps. Of these, 42,889 died whilst in the camp and a further 756 were sentenced to death and executed. In other words, although the absolute figures for internment were similar to those in the American and British zones, the rate of death in the camps (35 per cent) was far higher in the Soviet camps even though conditions in some of the American and British administered ones were far from adequate. In 1984, when the mass graves of somewhere between 6,000 and 13,000 inmates were discovered in Buchenwald, the communist authorities decided not to mention the fact in the new exhibition which opened in the former camp the following year. In the western zones, former concentration camps such as Dachau, Neuengamme, Flossenbürg, and Esterwegen were also used to house German suspects, including suspected war criminals and camp guards, but conditions in them, though unpleasant, were never as harsh as in the Soviet special camps. This was because the latter were tools of the social reorganization that the communists were engineering in Eastern Europe, by which ‘antifascist democracy’ would emerge on the basis of the destruction of the bourgeoisie as a class. By early 1950, the special camps’ useful life span had ended and, now for the most part empty of DPs and German suspects, they either fell into disrepair or became museums.

One of the characteristics of the Soviet special camps that allowed the Soviets to act with impunity was the camps’ ‘colonial setting’. The Soviet occupation zone, later the GDR, was the westernmost outpost of Stalin’s desire to establish ‘friendly regimes’ on the Soviet Union’s borders. In the German case, Soviet security—that is, not having to fear a German invasion—was absolutely crucial. Even though there was a sizeable domestic support for communism, unlike in, say, Romania, nevertheless the process of Stalinization (as opposed merely to communization) meant that German communist leaders who had been trained in Moscow and would do Moscow’s bidding were essential. The country became essentially a Soviet colony.

The point is worth making because in colonial settings, as we saw in Chapter 2, the tendency of the metropole to abandon the rule of law and to create and ‘manage’ superfluous populations is clear. The Jews in Cyprus got off lightly by comparison with the victims of British and French colonial violence in other settings, most notably in Kenya and Algeria. In both cases, concentration camps were employed to terrible effect.

Strikingly, several authors refer to the ‘Gulag’ in the context of the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya. More people were detained in Kenya than anywhere else in the British Empire, with a maximum of 71,346 detained in December 1954, the vast majority of them (98 per cent) from Kenya’s Kikuyu-speaking central highlands. Historian David Anderson calculates that ‘at least one in four Kikuyu adult males were imprisoned or detained by the British colonial administration at some time between 1952 and 1958’. Kenya already had a higher number of prisoners than neighbouring British colonies of Uganda and Tanganyika, but when the ‘Emergency’ began in 1952 it increased rapidly. As part of Operation Anvil in 1954, further camps were built, and the use of forced labour—contrary to international law—was sanctioned by Oliver Lyttleton, Secretary of State for the Colonies in Churchill’s Tory government. Operation Anvil itself was ‘Gestapolike’, as loudspeakers were set up in Nairobi and a 25,000-strong security force cordoned off the city to search it sector by sector in order to ‘purge’ it, a technique that the British had previously deployed in Tel Aviv.

The camps emptied out quite rapidly as of 1955, but by the end of 1958, 4,688 so-called ‘hard core cases’ who had refused to confess to being part of the Mau Mau movement were still being held. Almost all of them were held under the Emergency Powers on suspicion of supporting the Mau Mau and were never formally charged. Anderson, building on work done by other scholars, claims that the description of the Kenyan camps as ‘a Kenyan Gulag’ is ‘tellingly accurate’ (see Figure 8). Violence was routine, torture commonplace, the British guards were not properly trained and could do what they liked, disease was rife, and the demand that prisoners confess before they could be ‘rehabilitated’ smacks of Kafkaesque communist ‘re-education’ routines. Prisoners were routinely humiliated and deprived of food; as one, Nderi Kagombe, writes, ‘We would be starved for as many as six or seven days; then Mapiga [“the beater”, the nickname of the guard] would have the askaris bring in huge quantities of porridge and force us to eat it. Having not eaten for so long, it was very painful’ (cited in Elkins). Historian Caroline Elkins controversially writes that the Kenyan camps ‘were not wholly different from those in Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia’ and suggests, provocatively, that in these camps (known as the ‘Pipeline’) ‘Britain finally revealed the true nature of its civilizing mission.’ The slogan placed at the entrance to Aguthi Camp read: ‘He Who Helps Himself Will Also Be Helped.’

8. One of the Mau Mau camps.

The extent of the torture and brutal rule that characterized the British camps in Kenya has become clearer in the last decade. The same is true of the camp system established by the French in the context of the Algerian War (1954–62). In France, however, the difficult discussions about Algeria have been going on for longer; unlike Kenya, Algeria was administered as a part of mainland France, not a colony, and the fight to retain it united almost all shades of French political opinion. During the years of the war, some 2.3 million people were driven out of their villages and ‘resettled’ in some 2,000 camps de regroupement—in other words, a third of the rural population. The inmates depended on the army for their basic necessities, the hygiene conditions were appalling, and one historian notes that they were no more than ‘fenced-in tent camps’. After 1958, with de Gaulle’s return to power, plans to improve conditions and turn the camps into ‘new villages’ were announced but by 1962 only very few had been built. Unsurprisingly, the camps which were supposed to stem support for guerrillas—in Kenya, Algeria, and many other examples from Rhodesia to Vietnam—had the opposite effect. And where resettlement succeeded, as in Malaya, ‘it usually did so not because of any economic benefits it generated for a majority, but through sheer force’, as historian Christian Gerlach reminds us.

French plans to create ‘new villages’ were echoes of other colonial settings. In Malaya, for example, the British tried to separate the communist guerrillas from the jungle inhabitants through forced resettlement plans. The 1952 Briggs Plan envisaged moving 570,000 peasants and ‘squatters’ to 480 enclosed new villages. The plan’s remit was not just military: it also foresaw a reorganization of Malaya’s socio-economic structure, in particular the integration of the Chinese population into the rural economy. In Kenya, the colonial authorities intended something similar. Called ‘villagization’, the plan to resettle the Kikuyu population in some 800 barbed-wire enclosed camps and villages was one of the main drivers of the Mau Mau uprising.

It was ironic, to say the least, to see the armies of the liberal democracies—not least that of France, which regarded itself as the heir to the French Resistance, and that of Britain, which prided itself on defeating fascism—using violence involving carpet bombing, expulsions, massacres of civilians, and torture in attempts to suppress anti-colonial movements. And the use of camps during this process was most distressing of all for anyone who associated the liberal democracies with the liberation of camps, not with running them. As the historian Moritz Feichtinger says, ‘Nowhere was the universal promise of human rights more unmasked as rhetoric and nowhere did late colonialism reveal its murderous face as plainly as in its use of internment and torture, which took place in a broadly-spread out camp system.’

Communist camps

As we have seen (Chapter 4), in the post-Stalinist Soviet Union, although a huge number of Gulag inmates were released, the camps continued to exist with a focus more squarely on political dissidents. Across the communist world, camps remained in force. For a brief period they ‘flowered’ in the newly acquired satellite states of Eastern Europe but they were most willingly employed further east, in the newer communist countries of China and Cambodia.

Perhaps the most notorious of the East European communist prison camps was established in Romania. In that country, communism had almost no local support and had to be brutally imposed. Tens of thousands of Romanians were deported to camps or to work on slave labour construction projects, most infamously the Danube–Black Sea Canal. The years 1958–62 were ones of ‘blind, paroxystic repression’, according to Joël Kotek and Pierre Rigoulot, with mass arrests, deportations, and executions. 180,000 Romanians were in camps in the 1950s. But even before that, one particular prison had become, in the years 1949–52, the site of some of the most gruesome experiments with human beings. In Piteşti, a draconian scheme known as ‘re-education by torture’ was introduced, whereby political prisoners, mostly former members of Romania’s fascist Iron Guard, were offered freedom from prison and employment in the security forces if they would torture fellow prisoners and extract information from them. Led by Eugen Ţurcanu, a group of torturers put this process into action on 6 December 1949. The numbers killed were small—thirty in Piteşti and thirty-four others at other prisons—but many hundreds more were tortured; the process was only stopped when the Western press got wind of it and, in order to dissociate itself from the outrageous actions, the communist authorities tried and executed Ţurcanu and seventeen others.

But the clearest instantiation of the communist camp logic was found in Democratic Kampuchea, that is, Cambodia under Khmer Rouge (KR) rule from 1975 to 1979. It is no exaggeration to say that the KR aimed—and to a large extent succeeded—in turning Cambodia as a whole into a giant concentration camp. This aim did not emerge out of nowhere, a murderous political project in a historical vacuum. Cambodia was caught up in the Vietnam War, with the US Air Force dropping 2,756,941 tons of bombs on the country, much of it indiscriminately. The bombing, according to one Yale University report, ‘drove an enraged populace into the arms of an insurgency that had enjoyed relatively little support until the bombing began, setting in motion the expansion of the Vietnam War deeper into Cambodia, a coup d’état in 1970, the rapid rise of the Khmer Rouge, and ultimately the Cambodia genocide’. With what we might call their ‘Stalinist-peasantist-fascist’ ideology—a mixture of ultra-collectivization, a rejection of city life and worship of cultivation, and an obsession with Cambodia’s ‘glorious past’, the Khmer Rouge closed Cambodia off from the rest of the world. Democratic Kampuchea cleared the cities, demonized the so-called ‘new people’ who lived in them (in contrast to the ‘base people’ who worked the land), rejected anything to do with the Western world, from industrial technology to the wearing of glasses, murdered non-Khmer minority groups, and forced an inhumane system of communal living on its people. At the heart of this cruel and superstitious system was an actual camp: Tuol Sleng or S21. A mark of the regime’s paranoia, the camp was where Khmer Rouge cadres were tortured on suspicion of being Vietnamese agents—naturally without any basis for the fear—before being executed at Choeung Ek, the ‘killing fields’ ten miles south-east of Phnom Penh. Only a handful of people are known to have survived Tuol Sleng; some 14,000 were murdered there. Its existence in the midst of a giant camp (Cambodia) tells us what the system could be distilled down to: fear, paranoia, self-destruction, and extreme violence. Its commandant, Kaing Guek Eav, known as Comrade Duch, claimed that ‘We were destroying the old world in order to build a new one. We wanted to manufacture a new conception of the world.’ Cambodia’s extreme case illustrates the ultimate logic of concentration camps: causing destruction in the name of creation.

The Khmer Rouge’s self-destructive ideology was exposed when Vietnamese troops occupied the country in 1979 and the first foreigners to see Cambodia for four years were readmitted. In China, by contrast, the camp system has remained largely out of sight—to foreigners—for decades, rightly being termed the ‘forgotten archipelago’ by Jean-Luc Domenach. China, write Philip Williams and Yenna Wu, the authors of one study of the camp system, ‘endured more than its share of concentration camps during the 20th century. Moreover,’ they go on, ‘China is the only major world power to have entered the 21st century with a thriving concentration camp system, which has been commonly known as “the laogai system” [laodong gaizao zhidu] since May 1951.’ Of course, in China one cannot refer to ‘concentration camps’, only to ‘remoulding through labour facilities’ or ‘re-education through labour facilities’. The term ‘concentration camp’ is freely used by emigrants who have published their memoirs abroad, as one might expect; but scholars have also found the term applicable. ‘While considerable variability among the camps is naturally present in a country as large and diverse as China,’ Williams and Wu write, ‘the living and working conditions in their camps have often evoked the harshness associated with concentration camps, particularly during spikes in the death rate such as the record-breaking famine of 1959–62.’

As in the Soviet Union, the laogai system has also been characterized by the forced settlement of those formally ‘freed’ from the camps. When Harry Wu, who has done more than any other former inmate to bring the laogai to the attention of Westerners, returned to China in 1991 to make a film about the camps for CBS, he met a former prisoner named Zhou. Having served eight years from 1956 to 1964 for ‘counterrevolutionary crimes’, Zhou then remained in Xining, the capital of Qinghai province, for a further twenty-seven years. He told Wu that one third of the province’s population were resettlement prisoners and their families. ‘Their labour’, writes Wu, ‘had been used, he told me, to reclaim wasteland, construct roads, open up mines, and build dams, not just prior to 1979 but throughout the 1980s.’ In other words, more so than in the Soviet Union, the labour of laogai prisoners was economically beneficial to the Chinese Communist Party; the goods manufactured by the prisoners ‘are sold in domestic as well as foreign markets and have become an indispensable component of the national economy’. This claim is hardly surprising when one considers the numbers involved. In 1992, Harry Wu estimated that at least fifty million people had been sentenced to labour reform camps over the previous forty years and that sixteen to twenty million were still confined in them. Thought reform through labour turned out to be a convenient way of acquiring ‘a dependable source of wealth’, as Luo Ruiqing, the Public Security Minister, put it at the Communist general assembly of 1954. The laogai system was formally abolished in 2013 but the structure of the system remains: prison factories, psychiatric prisons, community correction centres, and other forms of extrajudicial incarceration all still exist, according to campaigners.

Although it seems likely that prison camps still exist in China, the last major communist camp system is that in North Korea. It remains very difficult to acquire reliable information but there is no doubt that a network of concentration camps holding some 150,000–200,000 people exists in that country, camps which are likely to become increasingly harsh as the country heads ever more towards catastrophe. One of the few memoirs by a former inmate is Kang Chol-hwan’s The Aquariums of Pyongyang. Following his grandfather’s arrest, Chol-hwan’s family (apart from his mother, the daughter of a ‘heroic family’) was deported to Yodok camp as the family of a criminal. Although, he says, the case could seem like one of ‘simple banishment’ to a place where those ‘contaminated’ by the proximity of a criminal could be ‘redeemed’, in fact ‘the barbed wire, the huts, the malnutrition, and the mind-quashing work left little doubt that it really was a concentration camp’. Chol-hwan was to spend ten years growing up in the camp. What did he learn?

The only lesson I got pounded into me was about man’s limitless capacity for vice—that and the fact that social distinctions vanish in a concentration camp. I once believed that man was different from other animals, but Yodok showed me that reality doesn’t support this opinion. In the camp, there was no difference between man and beast, except maybe that a very hungry human was capable of stealing food from its little ones while an animal, perhaps, was not. I also saw many people die in the camp, and their deaths looked like that of other animals.

(Aquariums of Pyongyang, p. 160)

Sadly, these communist camps are by no means the last examples of concentration camps in the modern world. Camps existed in the right-wing dictatorships of Argentina and Chile and, tellingly, in the context of the genocide in Bosnia, where images of Omarska and Trnopolje opened the world’s eyes to the fact that what was taking place in the wars of Yugoslav succession was not merely ‘typical Balkan tribalism’. The Wikipedia entry for ‘list of concentration and internment camps’ has entries for over forty different countries, including Sweden, Sri Lanka, and Montenegro as well as the more obvious examples.

This chapter has shown just some of the many locations in which concentration camps, or sites like concentration camps, have existed since the Second World War. The evidence suggests first, that concentration camps constitute a world-wide phenomenon which has developed over time as different states and regimes have learned from others in other parts of the world and, second, that these institutions, especially because they emerge in different settings under very different political regimes, tell us something fundamental about modernity and about the modern state. Precisely what that ‘something’ is will be the subject of the final chapter.