2

The Scribe’s Convictions and Methods

Different maps serve different purposes. Online maps allow people to choose whether they want to see a street view, a satellite view, or a road-map view. Other websites provide elevation cartography, climate statistics, county boundaries, political precincts, or school-district borders. None of these maps is better than the others; they merely serve different purposes. In the same way, while the rest of the book may be compared to a road map with all the same items (such as restaurants) in one area selected, then this chapter can be related to an altitude perspective, where the basic shape of nations or states can be viewed. Before we zoom in on Matthew’s wisdom through his narrative, it is helpful to back up and get a wide and expansive view of Matthew’s convictions and methods.1 If Matthew is the discipled scribe who learned wisdom from his sage, then his convictions and method are a part of the wisdom he seeks to transmit to the nations.

While my larger argument is that Matthew brings forth treasures new and old, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Below the water are assumptions and methods that need to be explored. My proposal for what subtly rests beneath the surface for Matthew is the following: Matthew learned from his teacher that the arrival of the apocalyptic sage-messiah fulfills the hopes of Israel; this results in the unification of Jewish history. The method Matthew employs to communicate this conviction is “gospel-narration” through the use of shadow stories. Matthew as the scribe brings out treasures new and old because his teacher-sage has revealed to him the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven (11:25–30; 13:51–52). The rest of this chapter expands on each of these assertions.

| Conviction | Israel’s hopes fulfilled |

| Basis/grounds | The arrival of the apocalyptic sage-messiah |

| Result | Jewish history is unified |

| Method | Shadow stories |

Fulfillment

Matthew’s main conviction concerning the relationship between the old and the new can be summed up in the word “fulfillment” (πλήρωμα).2 Jesus himself taught Matthew this in his statement about the messiah’s relationship to the Law and Prophets. “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matt. 5:17). He fulfills the Law and Prophets as the wise messiah. Law and wisdom are fashioned together, as evidenced by Deut. 4:5–8: “I have taught you decrees and laws . . . so that you may follow them. . . . Observe them carefully, for this will show your wisdom and understanding to the nations” (NIV).3 Matthew uses πληρόω or a form of it sixteen times in his Gospel compared to twice in Mark and nine times in Luke.4 This section will assert two things. First, I will argue that “fulfillment” means to bring something to fruition in the eschatological sense and is not always tied to predictive prophecy. Second, I will examine the location of the fulfillment formulas, displaying that the theme of fulfillment covers not only sections of the First Gospel but Matthew as a whole.

Declaring fulfillment to be a central theme might seem like a simple statement, one many have made, but the proposals for what πληρόω means are legion.5 Lexically, BDAG (827) gives at least three options for the gloss of the term: (1) to make full; (2) to complete a period of time, or that which was already begun; (3) to finish, complete, or bring to a designated end. Three depictions are contained in these descriptions. “To make full” is a spatial metaphor, like filling a cup. “To complete a period of time” is a temporal comparison, such as when a person reaches a certain age. “To bring to a designated end” is a logical association. These assorted descriptions are not contradictory but complementary. Words are not like hardwoods, which are difficult to twist and cut through. Words are more like softwoods, with flexibility and pliability but also strength determined by their respective contexts. “Fulfill” has a variety of meanings, and in different contexts certain aspects might be highlighted. Yet largely, we can say that it means that Jesus fills up Jewish history, he completes the time of Israel, and he brings Israel to its logical telos. Another way to put it is that Matthew learned from his teacher that all things are brought to fruition in and through Jesus.

The term πληρόω should thus be understood in an eschatological sense: Jesus becomes all that the Law and Prophets have pointed to. He is the terminus, the telos of the Hebrew Scriptures. A new epoch has come with Jesus. The nature of πληρόω assumes a before, center, and after. What came before was not the peak of fulfillment; only at the pinnacle of time is fulfillment found (Gal. 4:4). Fulfillment uncovers its substance at the crosshairs of time. Matthew uses this term because he sees it as bridging the gap between the new and the old. All of the promises made in the OT, all of the predictions spoken, are now “filled up” in Jesus Christ. He fulfills the Law and the Prophets by becoming the one to whom the Law and Prophets point. Jesus is the end of the law, the satisfaction of all of Israel’s history. As Moule says, “Jesus is . . . the goal, the convergence-point of God’s plan for Israel, his covenant-promise.”6 Jesus, through his coming, begins a new era.

“Fulfillment” also means more than prediction. According to Matthew, the OT gives us types and predictions.7 As Hays affirms, contrary to first impressions, it is inaccurate to characterize Matthew’s method as prooftexting or on a prediction/fulfillment model.8 This is because Matthew’s use of “fulfillment” does not simply mean the completion of a previous prediction, although that is what English readers normally assume. For example, the following formula quotations arguably do not introduce a messianic prophecy in their strict historical context: 1:22 (virgin birth); 2:15 (son called out of Egypt); 2:17 (Rachel weeping); 13:35 (opening mouth in parables); and 27:9 (thirty pieces of silver). They are messianic after Jesus has come but only because he fills up their meaning. For Matthew, the word “fulfillment” “stands as an invitation to view Israel’s Scriptures as the symbolic world in which his characters and his readers live and move.”9

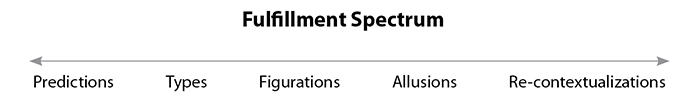

Pennington therefore speaks of a fulfillment spectrum. “Fulfillment . . . does not depend on prediction per se, while it still leans forward to a time when God will bring to full consummation all his good redemptive plans.”10 Prediction is a subset of the bigger ideas of fulfillment or figurations.11 According to the fulfillment spectrum that Pennington proposes, “The way the Jewish Scriptures are re-contextualized and re-read and re-understood in light of Jesus is varied—sometimes predictions are fulfilled, while sometimes texts are taken up and re-applied in a new way, and everything in between.”12 He represents it visually like this.

Matthew seems to represent all of these ways of reading, and we must have a model that accommodates all of Matthew’s strategies and does not sideline some of them or overemphasize one of them.13 The overall point is that “fulfillment” is the word Matthew employs to teach future disciples about the relationship between the new and the old, and it expresses the eschatological, spatial, temporal, and logical dimensions of Jesus’s relationship to Jewish history. It includes predictions, but also much more because it is an eschatological concept.

The Location of the Fulfillment Formulas

While it would be a mistake to focus only on the times the word πληρόω is used, now is a good time to look at the fulfillment quotations as a whole since they will be divided up and parsed throughout the rest of the work.14 As is well known, Matthew’s Gospel contains ten fulfillment quotations that follow a certain formula: “to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet, saying . . .”15 The existence of the fulfillment quotations helps readers ascertain the fulfillment theme. Of all the Gospels, Matthew is the most explicit in letting his readers know that Jesus fulfills the hopes of Israel. Yet the placement of these quotations has caused much consternation. At first glance, the distribution seems haphazard.

The two chapters of the infancy narrative contain four fulfillment quotations. The next thirteen chapters of Matthew’s Gospel concerning Jesus’s Galilean ministry also include four, and then the rest of the Gospel (almost thirteen chapters long) contains only two fulfillment quotations. The fulfillment quotations drop off at a stunning rate.

| Location | Number of fulfillment quotations | Percentage per chapter |

| Infancy narrative (1–2) | 4 | 20% |

| Galilean ministry (3:1–16:12) | 4 | 3% |

| Jerusalem and beyond (16:13–28:20) | 2 | 1.5% |

This distribution is odd because Matthew is a rather systematic author. Is Matthew indicating that the beginning of Jesus’s life fulfills Israel’s Scriptures more than the end? M. J. J. Menken has provided a convincing explanation for the uneven distribution of the fulfillment quotations:16 “The distribution seems at first sight rather arbitrary but on closer consideration it appears to be well-thought out.”17 Matthew sets up his story in the infancy narrative, making sure his readers don’t miss the fulfillment theme. Then the rest of the fulfillment quotations in the Gospel are placed in summary sections that do not cover only one little detail of Jesus’s life but rather large swaths of Matthew’s narrative. In other words, as the fulfillment quotations continue, they function like hedges blocking in large gardens of Matthew’s material. For example, during Jesus’s ministry in Galilee, the four fulfillment quotations (4:14–16; 8:17; 12:17–21; 13:35) have been added not to individual narratives but to summaries that describe the general traits of Jesus’s ministry.

In Matt. 4:14–16 the fulfillment quotation is a summary of Jesus’s ministry in Capernaum: “The people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light, and for those dwelling in the region and shadow of death, on them a light has dawned” (4:16). In. 8:17 the quotation speaks of Jesus taking illness and bearing diseases: “He took our illnesses and bore our diseases.” This comes in the middle of two chapters (8–9) and covers all of Matthew’s first presentation of Jesus’s deeds. In chapter 12 the antagonism against Jesus grows while Jesus heals outsiders, and a significant shift toward a gentile audience occurs. So, in 12:17–21 Matthew quotes from Isaiah, speaking of Jesus as proclaiming justice to the gentiles (12:18). Finally, 13:35 comes partway through the kingdom parables chapter, and there Matthew quotes from Ps. 78:2, saying that Jesus will speak to them in parables. Matthew therefore, as the narrative continues, inserts the fulfillment quotations at key junctures of his narrative to summarize Jesus’s words and actions for multiple chapters.

The same pattern occurs in the Jerusalem narrative (16:13–28:20). Although here Matthew uses only two explicit fulfillment quotations, his strategy has not changed. The first fulfillment quotation occurs in 21:4–5 and tells of Jesus coming to Zion on a donkey. “Behold, your king is coming to you, humble, and mounted on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a beast of burden” (21:5). This quote again does not merely summarize the chapter in front of it, but reaches all the way back to Peter’s confession, when Jesus says he must go to Jerusalem (16:21). A few times Matthew draws attention to Jesus’s journey to Jerusalem (19:1; 20:17–18; 21:1), and Jerusalem is finally reached in 21:10. Therefore the journey to Jerusalem, started back in chapter 16, comes to fulfillment when Matthew (21:5) quotes Zechariah (9:9).

In a similar way, the function of the fulfillment quotation in 27:9–10 is the final point of rejection by the Jewish authorities. “They took the thirty pieces of silver, the price of him on whom a price had been set by some of the sons of Israel” (27:9). Though this is a specific quotation, the antagonism toward Jesus in the narrative thread actually begins in chapter 12, when the Pharisees decide that they will destroy Jesus (12:14). In chapter 27 this antagonism and betrayal comes to a climax. So both fulfillment quotations in Matt. 16:13–28:20 are part of pericopes in which important narrative threads come to an end: Jesus’s journey to Jerusalem and his rejection by the Jewish authorities.18

The Fulfillment Quotations and Large Narrative Blocks

| Topic | Fulfillment quotation | Narrative block |

| Ministry in Galilee | 4:14–16 | 4:12–16:20 |

| Suffering servant who heals | 8:17 | 8:1–9:38 |

| Servant’s ministry to Gentiles | 12:17–21 | 4:12–16:20 |

| Speaks in parables | 13:35 | 13:1–58 |

| King comes humbly to Jerusalem | 21:4–5 | 16:21–21:10 |

| Rejection of Jesus | 27:9–10 | 12:14–28:20 |

Although Matthew’s use of fulfillment quotations sharply declines throughout his narrative, Matthew is not haphazard with his placement of them, and they color the way readers engage the entire Gospel. Matthew begins with more fulfillment quotations to let his readers in on his strategy. It is as if he shouts his themes at the beginning to wake his readers up, and then he quiets down when he knows they have caught on.19 Therefore he diminishes his explicit use of OT quotations, allowing his interpreters to go searching for more clues in his narrative. It is not merely the infancy narrative where Jesus’s life is mimicking OT events, institutions, and persons but his entire life. At key junctures in the narrative, Matthew places fulfillment quotations to show that all of Jesus’s life is in fulfillment of Jewish hopes.

We have seen how Matthew spreads out his fulfillment quotations, thereby showing us that all of Jesus’s life fulfills the OT. Many studies on Matthew have too much of a love affair with the fulfillment quotations, neglecting and abandoning the other Matthean allusions. There is much more to explore in Matthew, and therefore the rest of the book will also look to the less explicit references. We have also looked at how fulfillment should be understood in the eschatological sense and how it functions as a summary of Matthew’s conviction for his scribal work: Jesus fills up, completes, perfects the history of Israel. This is Matthew’s major conviction, which caused him to write about Jesus in the form he did. Now we need to turn to the reason Matthew wrote a fulfillment document.

Appearance of the Apocalyptic Sage-Messiah

The conviction that the fulfillment of all things has come is based on the arrival of the apocalyptic sage-messiah. Each of these terms will be taken in turn. First, the arrival, the coming, the appearance of Jesus is the key that unlocks the fulfillment door. While many works on Matthew focus on fulfillment, few explicitly tie this to the coming of Jesus—not because commentators disagree with this, but because it is assumed. Yet when we assume something, it gets sidelined. While the coming of Jesus centers on his incarnation, it is not limited to it. For the biblical authors, the incarnation and atonement of Jesus are two sides of the same coin.20 To put this another way, the incarnation paves the way for atonement.21 Though the purposes for Jesus coming to earth are numerous, one of the key reasons is to teach his people wisdom as the messiah and thereby reestablish the relationship between God and human beings and bring forth the kingdom. This happens through the incarnation, instruction, and ultimately the death of the God-man on the cross. Matthew writes because Jesus has appeared on earth, taught him about the kingdom of God, and died for the sins of his people. Wisdom personified suddenly has appeared in history, and things must change after his coming. The appearance of Jesus is the most basic cause for Matthew seeing things in terms of fulfillment. To put this negatively, without the emergence of Jesus, there is no fulfillment.

Second, Jesus’s coming is apocalyptic. Though this term runs the risk of overuse, it still retains the sense I am attempting to get across. What I mean here is not that Matthew’s writing is an apocalypse; rather, in Matthew Jesus reveals mysteries. He reveals the secrets of wisdom.22 Matthew as the scribe of Jesus’s life may employ an apocalyptic worldview without writing an apocalypse per se. Hagner goes so far as to say, “From beginning to end, and throughout, the Gospel makes such frequent use of apocalyptic motifs and the apocalyptic viewpoint that it deserves to be called the apocalyptic Gospel.”23

Orton emphasizes the apocalyptic nature of scribal activity. He found in Sirach, apocalyptic literature, and the Qumran documents “that the principle underlying true scribalism . . . is that the teaching offered by the true scribe derives from divine revelation; it is a matter of inspiration. This is reflected constantly in the emphasis on God-given insight, the claim to special access to divine mysteries, and on the ideal scribe’s commission to instruct his posterity in understanding and true righteousness.”24 In light of scribal backgrounds, Orton asserts, the apocalyptic understanding works far better than some notion of Matthew as a rabbinic author.25

Jesus’s coming is apocalyptic not only in that it is revelatory but in that it is an upheaval, a liberating invasion of the cosmos. The turning of the ages occurs; the introduction of a new epoch begins. Jesus enters not merely the history of the first century but the history of the cosmos. His crucifixion is the crucifixion of the cosmos; sin and death are now defeated. New creation invades the present evil age. The first words of Matthew are evidence of this: βίβλος γενέσεως. This phrase harks back to the creation of all things in Gen. 2:4 and 5:1. Jesus is inaugurating the new heavens and the new social order in the midst of a world of darkness.

Apocalyptic thus maps onto the term “new” in Matthew’s new-old paradigm. While continuity exists with what came before, there is also discontinuity.26 Modern “biblical theology” may be too focused on stability and continuity, not recognizing that the arrival of Jesus upsets the political, social, and religious orders (even Jewish orders!). Mystery and newness surround Jesus. Matthew is the scribe who brings out the “new” and the “old” (καινὰ καὶ παλαιά, 13:52). The instigation for Jesus’s death is evidence of the newness of Jesus’s message. If he merely came and did all that the first-century Jewish leaders expected, then he would not have been crucified. There is new revelation––the secrets of the kingdom of heaven are exposed.

Third, Jesus comes as the apocalyptic teacher-sage. Jesus comes in Matthew as the personification of wisdom. As Witherington argues, it may be that the personification of wisdom arose partly because although it was understood that wisdom was hidden, Jews also believed that their God was one who revealed himself. Their God reveals wisdom to his people. A particularly key passage for this comes from Matt. 11:25–27.27 The context begins with John the Baptist asking Jesus who he is, for he has heard of “the deeds of Christ” (τὰ ἔργα τοῦ Χριστοῦ, 11:2). Jesus answers with a quote from Isaiah, who also prophesied that the Spirit of wisdom would rest on the messiah. The short episode ends with a reference to the deeds of wisdom (ἡ σοφία ἀπὸ τῶν ἔργων αὐτῆς, 11:19) paralleling the “deeds of Christ” in 11:2.28 Yet in 11:20–24 Jesus denounces the towns he has traveled in because they have rejected him. This leads Jesus to thank his Father in heaven for having “hidden these things from the wise and understanding and revealed them to little children” (11:25, emphasis added). Many key wisdom terms and concepts occur here: revelation, hidden, wise, understanding. Jesus goes on to say, “No one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him” (11:27).29 As the messiah, Jesus was the apocalyptic inbreaking of Wisdom into this world. He was the very embodiment of wisdom, the incarnation of the kingdom of heaven.

This is further supported by the nature of Jesus’s sayings in the Gospels. Though we usually think of Wisdom literature as a fixed form, such as parables or short sayings, we should remember that since there is considerable influence of the wisdom tradition on the prophetic tradition, the whole of Scripture could be described as a wisdom text.30 Therefore it might be that our view of the wisdom tradition is narrower than the ancients’ view. For example, the Wisdom of Solomon (composed around the first century AD) offers extended exhortation in discourse form and chooses to offer something of a historical review. The prophets seemed to take this wisdom tradition and modify it into narrative form to serve their concerns. Jesus as the teacher-sage drew on a variety of Israelite traditions so that he could intermix aphorisms and narrative meshalim. In fact, most of his material takes one of these two forms. Scribes were responsible for the preservation and production of all sorts of genres. However, the narrative nature of Matthew’s Gospel should also not blind readers to the particularity of Jesus’s teaching. Witherington even says that by a conservative estimate, at least 70 percent of the Jesus tradition is in the form of some sort of wisdom utterance, such as an aphorism, riddle, or parable.31

I submit that the vast majority of the Gospel sayings tradition can be explained on the hypothesis that Jesus presented himself as a Jewish prophetic sage, one who drew on all the riches of earlier Jewish sacred traditions, especially the prophetic, apocalyptic, and sapiential material though occasionally even the legal traditions. His teaching, like Ben Sira’s and Pseudo-Solomon’s before him, bears witness to the cross-fertilization of several streams of sacred Jewish traditions. However, what makes sage the most appropriate and comprehensive term for describing Jesus is that he either casts his teaching in a recognizably sapiential form, or uses the prophetic adaptation of sapiential speech—the narrative mashal.32

Though I disagree with Witherington that “sage” is the most comprehensive term, it is one term among many that throws light onto Jesus’s life and Matthew’s recounting of it. The implication of Jesus’s various wisdom sayings indicates the presence of Wisdom on the earth in the arrival of Jesus.

Fourth, the substance of this conviction revolves around the term messiah. Although early Jewish literature cannot produce a checklist of what the messiah will do, and there were diverse opinions about the messiah, we can read backward from Matthew’s presentation to get a better understanding of what was expected.33 Many biblical scholars are wary of appealing to later writings, thinking that they confuse and distort our picture of early Jewish hopes. In other words, they assert that it is anachronistic to force later views on earlier texts. But could it be that the passing of time clarifies anticipations rather than concealing them? The coming of Jesus actually defines the hope rather than obscuring it. As Wright says, although we can’t re-create a single unified picture of Jewish messianic expectation, such expectation, though not unified, certainly existed. “The early Christians . . . took a vague general idea of the Messiah, and redrew it around a new fixed point, this case Jesus, thereby giving it precision and direction.”34

W. D. Davies argues that Matthew redraws and defines messianism around David, Abraham, Moses, and the Son of Man.35 The genealogy begins by asserting nothing less than that Jesus of Nazareth is Israel’s long-awaited messianic king. While the Davidic connotations govern Matthew’s presentation, they are also balanced by Matthew’s description of Jesus as the son of Abraham. Messianism is defined by both a particular and a universal focus. Jesus is a Jewish messiah whose goal is to bless the nations. But he is also the new messianic Moses who fulfills the law by both accomplishing all and teaching others to do the same. By being the Danielic Son of Man, Jesus also balances out these portraits because he comes as judge. As Davies notes, messianism also has a dark side: it can lead to unrealistic, visionary enthusiasms that prove destructive. Matthew tempers and defines those messianic hopes by fashioning the messianic hope according to these four figures.36

Wright argues that messianic hopes were transformed by the NT writers in at least four ways: (1) they lost their ethnic specificity and became relevant to all nations; (2) the messianic battle was not against the worldly powers but against evil itself; (3) the rebuilt temple would be the followers of Jesus; and (4) the justice, peace, and salvation that the messiah would bring to the world would not be a geopolitical program but the cosmic renewal of all creation.37 Messianic hopes were primarily transformed by the reality of a suffering messiah (as Isaiah predicted). The Gospel writers’ central conviction revolves around the cross. It is important to recognize here that the thread of messianic hope runs through diverse terrains, and readers can’t siphon them off and lock them in their respective rooms. Yet Matthew also employs the suffering messiah as the gravitational axis through which all the other terms travel. So while I won’t devote an entire chapter to Jesus as the suffering messiah, each chapter should be read as defining what Matthew means by asserting that Jesus is the Christ.

In sum, Matthew brings out the new because of the arrival of the apocalyptic sage-messiah who inaugurates the kingdom. Old Testament texts are consummated in the person and work of Jesus the Messiah. He is not taking out his “messianic searchlight” and finding texts that adhere to his program. The opposite is the case. Neither Matthew nor the NT has this searchlight, but the OT is the “messianic searchlight.”38 The messiah fulfills these hopes in that they were “shadows” before he came, but now these texts are “filled” with reality. What earlier was dark now comes to light in Jesus. Alternatively, to change the metaphor, the Prophets and the Law give a blurry or foggy view of the messiah. The bits and pieces are there, but when Jesus comes, the substance is now present. As Paul says, “All the promises of God are Yes and Amen in Christ Jesus” (2 Cor. 1:20 AT). Jesus satisfies the hunger for eschatological consummation throughout the OT story. Matthew’s theology inspires, determines, and controls his hermeneutical approach to the OT Scriptures. As Matthew writes, in every Scripture “something greater is here” (Matt. 12:6, 41–42). Every shadow dancing across the pages of Matthew’s narrative is cast by some greater eschatological substance. Matthew recalibrates these texts to have them refer to God’s apocalyptic agent.

History Unified

Because Jesus has come and fulfilled all things, the result is that Jewish history (and all history) is now unified. While the apocalyptic nature of the messiah maps onto the “new,” the newness paradoxically also brings forth the “old.” The Hebrew Scriptures are fulfilled in that their history is now viewed through the window of Jesus. History, at the most basic level, is about people, time, and place. In Matthew’s Gospel, all three of these meet in the messiah. The people (Moses, Abraham, David, et al.), the places (mountains, rivers, temple, desert, etc.), and time (new and old) all incorporate together under the banner of Jesus.

Time is presented in duality for Matthew as he constructs both a linear chronology and presses in on the reality of “higher time.” Linear chronology views time in sequence; “higher time” views events as not detached but joined together. For example, the exodus from Egypt happened in the past (chronological), yet it is also recapitulated (higher time) in Jesus’s departure from Egypt (Matt. 2:15).39 Robert Jenson put this another way: a biblical understanding recognizes time as neither linear nor cyclical but perhaps more like a helix, “and what it spirals around is the risen Christ.”40

This distinction is important to comprehend in Matthew. Chronologically speaking, Jesus comes on the scene at a certain time, after many events have been completed. But Matthew contends time can be compared to a casting net. When the center line is drawn up, the points on the edges are drawn together. For Matthew, the moments in the OT suddenly draw together at a higher time in the person of Christ. Higher time does not overrun linear time but recognizes the simultaneity of distinct, previously unconnected moments in time. Matthew does not impose alien meanings onto the biblical text and avoid historical meaning. Rather, he is persuaded that the OT events are contiguous with their christological fulfillment in the NT—a fulfillment often incomprehensible until the arrival of Jesus.

These assertions are similarly true about space and place in Matthew’s narrative. Many biblical theologies form time-based readings of the text, but a neglected area of reflection lies in the spatial perspective.41 For Matthew, places can be both separate and unified: Matthew conceptualizes separate mountains as coinciding, the water crossings as holding together in simultaneity, heaven as bending down to touch earth, and Jesus as looking out over the land in Matt. 28 as Moses did at the end of Deuteronomy. Earthbound events suddenly participate in heavenly realities because the God-man has come to be with his people.

The same casting net employed for time and space is also used for people. As the center line is drawn up, the people through the corridors of time begin to point toward their destination. Matthew draws the line, and suddenly Moses’s life is not black and white but filled with color; the promises to Abraham begin to fill out, the covenant with David is fulfilled, and all Israel as a nation mirrors the actions of Jesus. Because of Matthew’s conviction about history, his shadow stories can have multiple references. These manifold references are not contradictory but complementary. Is Jesus’s going through the water in his baptism a picture of Moses, Israel, Joshua, the new creation, or the kingdom? The answer is yes. These can all coalesce because Jesus is the gravitational force that pulls all things together.

Northrop Frye writes that the immediate context of a sentence is as likely to be three hundred pages off as to be the next or preceding sentence.42 This is because not only the characters participate in the drama of God; history itself, including time and space, does as well. “Jesus Christ constitutes the center of linear and participatory history as the Incarnate Word.”43 Another way of putting this is that Matthew’s theory of history is not one in which random fluidity is the core idea, but history progresses to a determined end. History has a telos. It is an arena of promise and fulfillment; it is the stage upon which the creator God speaks and acts.

The Scribe’s Methods

Convictions produce methods and techniques. For example, photographers will normally shoot at sunset because they are persuaded that the lighting is best at dusk. Their convictions drive their methods and systems. In the same way, the scribe’s method flows from his persuasions about his teacher. Matthew therefore tells the story of Jesus in (1) the form of an ancient biography, indicating how his subject is worthy of emulation. Another influence on Matthew’s writing is (2) the historical narrative of the Hebrew Bible. The early church and the evangelists understood the four narratives about Jesus as “gospels” and therefore as continuing the great story of God. The First Evangelist particularly shapes, embeds, and builds his narrative in the apparel of other Jewish texts. Shadow stories govern his presentation of the story of Jesus. For Matthew, the best way to show how Jesus disrupts and completes the story of Israel is to employ Israel’s texts in the repainting of Jesus’s life. The form of Matthew’s work (biography and OT narrative) conveys his conviction and the wisdom received from his sage: the new completes the old.

Genre and Purpose

Though some still argue that the Gospels are sui generis, the work of Richard Burridge has turned the tide toward viewing the Gospels as ancient biographies (βίοι), though with some differences.44 In the ancient world biographies presented their subjects as exemplars. Plutarch, for example, draws a distinction between comprehensive histories and the writing of his βίοι.45 “I do not tell all the famous actions of these men, nor even speak exhaustively at all in each particular case, but in epitome for the most part. . . . For it is not Histories that I am writing, but Lives; and in the most illustrious deeds there is not always a manifestation of virtue or vice.”46 Plutarch specifically says he does not include everything in a person’s life because he is concerned with the virtuous character of his subjects. This use of stories to promote moral exemplars is commonly used in Greco-Roman and biblical discourse. Matthew therefore puts his writing of Jesus’s life into this genre because he wants to encourage wisdom by highlighting the actions and teachings of his sage.

But readers must progress past the Greco-Roman tradition for influence upon Matthew. Major inspiration comes from the historical narratives of the Hebrew Bible.47 Early on, the term “gospel” began to be employed as a sort of genre description of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The term “gospel” (εὐαγγέλιον) and its verbal cognate “gospelize” (εὐαγγελίζω) point to the oral proclamation or message of good news. Why did the early church begin referring to these written documents as “Gospels”? The answer comes from looking at the first words of Mark, the first written Gospel. It has been widely argued that the opening words of Mark’s Gospel are not simply an introduction to his work but most likely serve as a title or heading: “the beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ υἱοῦ θεοῦ).

Not only do we have some hints in the evangelists’ works themselves that these should be labeled as “Gospels,” but the early church witness also supports this. As early as the first half of the second century (ca. AD 150–55), the noun εὐαγγέλιον was used in Justin’s Apology to refer to the Gospel books.48 In addition, the superscriptions added to the four evangelists in the second century were consistently “the Gospel according to X.” So the followers of Jesus early on seemed to follow Mark in labeling these works as “Gospels.” However, the more important question for this study is the implication of these being labeled as “Gospels.”

In the OT, and more specifically Isa. 40–66, the term “gospel” refers to the hope of the future restoration of God’s reign through his chosen servant. For example, in Isa. 52:7 εὐαγγελίζω is put in parallel to the reign of God (βασιλεύσει σου ὁ θεός).

How beautiful upon the mountains

are the feet of him who brings good news,

who publishes peace, who brings good news of happiness,

who publishes salvation,

who says to Zion, “Your God reigns.” (Isa. 52:7, emphasis added)

Therefore, when Jesus comes proclaiming “the gospel of the kingdom” of God (Matt. 4:23; 9:35), the disciples must have understood that Jesus’s ministry fulfills the hopes of which Isaiah spoke. It was thus appropriate for the disciples and the early church to label their stories as “The Gospel according to X” because in these stories we learn how Jesus satisfies the gospel expectations.49 The Gospels are stories about Jesus, and Jesus’s message is that the kingdom of God, the reign of God, is here in his person.

Matthew chooses to tell this “Gospel” because it completes the great story line of the Scripture. The trained scribe understood himself as continuing the ancient story of God’s dealings with his people, beginning with Adam and Eve and going through Abraham, Moses, and David. At its core the whole Bible is a narrative of God’s work in the world, and Matthew completes this portrayal with the story of Jesus. The hopes and dreams of Israel centered on the announcement of good news and more specifically the good news that their God reigns over the whole earth. Matthew, as the scribe, illustrates for his readers that his rabbi is the representative of God who will bring God’s kingdom. These are not just any stories, but stories of the Jewish messiah, the king from David’s line, the son of Abraham.

The combination of these two genres (ancient biographies and OT narratives) instructs readers both that Matthew presents Jesus as a figure to emulate and that this story is the climax of the great narrative of Israel. Matthew, and the other Gospel writers, take the wisdom sayings of Jesus and connect them with the narrative mode of the Hebrew Bible. According to Dryden this means that the Gospels function as wisdom: they “teach practical wisdom by instilling in readers a personal allegiance to a particular value-laden picture of the world.”50 Matthew writes of Jesus’s life in these particular forms so that we might see the values of Wisdom embodied as the new and the old intermix in his discourses and actions.

Shadow Stories

Matthew provides an ancient biography peppered with the Hebrew Bible. But we need to press more into the manner of how he tells this story of Jesus, for this instructs us about the wisdom learned from his sage. The First Gospel can be understood on a basic narrative-development level: Jesus is born, baptized, begins his ministry, is challenged, dies, and rises from the dead. Yet the shadows of the Torah nearly always shape Matthew’s historical rendering. The OT Scriptures constitute the “generative milieu” of Matthew’s story. It is somewhat like the baby boomers experiencing the first generation of Star Wars movies and then watching the 2015 installment The Force Awakens. The director J. J. Abrams explicitly made the film in a way that both new and old fans could appreciate. There was the basic plot line, which carried the movie forward, yet when Star Wars fans saw certain scenes, they couldn’t help but be reminded of earlier movies. The point is that there is the text (The Force Awakens), and then there is the subtext (earlier Star Wars films). They cohere with one another in some ways and differ in others, but those with ears to hear and eyes to see end up seeing more than the uninformed viewer does.

Yet exactly how Matthew (and the other NT authors) employ the OT is debated. The dispute pertains to both the terms used to describe the method and the actual practice behind these terms. Some prefer the name typology, others intertextuality, or inner-biblical exegeis, or figural representation, or midrash, or allegory.51 The division between these camps creates deep divides among interpreters (though there is probably more commonality than they realize). I don’t attempt to solve the debate here, but I do want to point out one oversight and attempt to correct it in my presentation. The problem with some of the aformentioned terms is that they unintentionally produce tunnel vision rather than viewing parallels together. If Matthew’s gospel-narration of Jesus’s life reflects and completes the persons, places, things, offices, events, actions, and institutions of the OT, then these should be viewed together.52 The combination of all these things produces a story.

I will therefore use the term shadow stories as the comprehensive term partially because shadow stories are unique to the Gospels’ narration.53 They connect large swaths of narrative rather than just points or dots in the story. The point here is to push people past simply looking for similar terms and to look for a combination of these factors and the development of a narrative through quotes, allusions, and echoes. The main importance of this is that as we study Matthew, we should be looking for more than “word” connections; we should watch for “narrative” echoes as well. Associations are made to Jesus’s life that demonstrate how all the types in the Hebrew Scriptures are fulfilled in the antitype. This makes sense, for a story consists not only of persons but also of events, institutions, things, offices, and actions.

So, for example, Jesus is presented as the new Moses (person). In portraying Jesus as the new Moses, Jesus is set on mountains (places) mirroring Sinai and other such imagery. At times, he is even portrayed in shining clothes (things), showing that he is near to God, like Moses. As the new Moses, Jesus is thus the new prophet (office), who speaks for God and leads his people on a new exodus (event). He does this by the sprinkling of his blood (action), which establishes the new covenant (institution). Readers should not take these out and only assess them individually, as if they stand on their own. Rather, they should examine how Matthew’s narrative develops the portrait of Jesus as the new Moses. The narrative as a whole is shaped in a way that imitates, duplicates, and replicates a previous story, not only individual pieces of it.

Explicit or Subtle?

Many scholars notice how explicit Matthew’s use of the OT is, and the abundance of fulfillment quotations support this contention, but Matthew can also be subtle.54 Sometimes his overt fulfillment statements distract readers from seeing other shadows dancing across his pages.55 Dale Allison says that while Matthew made much clear, he did not trumpet all his intentions; a careful reader will note this even in the first few verses.56 Matthew’s style is not only overt but also full of allusions and implications. It is not a contradiction to assert that Matthew is both explicit and subtle. He is explicit on the surface level but subtle on a deeper level. Sometimes the overt words of Matthew are plain so that a modest reader can get his point, but his form is subtle. Other times the individual words seem plain, but then when comparing them with an OT text, one realizes much more is going on.

For example, Matthew cloaks his introductory narrative about who Jesus is (chap. 1) and where he is from (chap. 2) with distinctly torahaic robes. Using a string of fulfillment quotations in chapter 2, Matthew shows his readers how to interact with his unfolding story. Jesus’s birth in Bethlehem is to fulfill the prophecy that a ruler will come from Bethlehem (Mic. 5:2). His life in Nazareth fulfills the expectation that he will be called a Nazarene (Isa. 11:1). On one level the meaning is plain, but when one examines the OT, no quote exists that says, “One is coming who shall be called a Nazarene.” Matthew surely knew this, so he must want his readers to see something more than what was on the surface. Many therefore conclude that Matthew executes a wordplay with Isa. 11:1, which says, “Then a shoot will spring from the stem of Jesse, and a branch from his roots will bear fruit” (NASB). In Hebrew, the word for “branch” is netzer, which in the Hebrew consonantal text would appear as NZR, the letters occurring also in NaZaReth. Matthew is thus explicit on one level but subtle on another.57

Matthew can be subtle, ambiguous, and “untidy” at times because, like a good artist, he knows words on a slant are sometimes more effective. In the words of R. T. France, there is a surface meaning but also a “bonus meaning” that conveys the increasingly rich understanding of the person and role of Jesus.58 The point is not that Matthew is “a verbal juggler, but [an] innovative theologian whose fertile imagination is controlled by an overriding conviction of the climactic place of Jesus in the working out of the total purpose of God.”59 The First Gospel is a mnemonic device, a trigger for intertextual interchanges that depend on an imaginative and careful reading.60 So Matthew provides stories about Jesus, but these stories have shadows lurking both in the foreground and the background. Some of these shadows have clear outlines, while others require more work on the part of the reader.

Reception and Production

As I have argued, Matthew is convinced that the coming of the apocalyptic sage-messiah has fulfilled Israel’s expectations. Shadow stories look more to the larger narrative patterns and note that events, persons, institutions, places, things, and offices can’t ultimately be separated. But how does Matthew find these figures and shadow stories? Does he read backward from Jesus’s life, or forward from the OT? David Orton is right to state that Matthew’s method was probably more natural than parsed out.

Matthew may not himself have been fully aware of the mechanics of his own method, since it plainly operates on an intuitive level, involving a high degree of lateral thinking and unconscious allusion. For Matthew the exercise is certainly not an academic one, some kind of word-game, or even a rabbinic-type exegesis; it is a product born of extended reflection and meditation on the written words of scripture and of his Jesus-sources.61

While Matthew may have not been aware of his mechanics, it is useful to step back with hindsight and categorize what he is doing. Matthew seems to employ a reading of both reception and production.62 Reception focuses on how Matthew received meanings generated by the OT text. Production refers to the way in which Matthew exposed or inserted meanings in earlier texts. In simpler terms, Matthew reads both forward and backward. He sees things latent in the OT text before Christ’s advent and also sees things that can be recognized only retrospectively, after the coming of Jesus.

While the prospective reading is not provocative, some are uncomfortable with a retrospective reading. Kaiser states, “If it is not in the OT text, who cares how ingenious later writers are in their ability to reload the OT text with truths that it never claimed to reveal in the first place?”63 I care, especially if Matthew the scribe is the one reloading the text. The crux of the argument comes down to what “in the OT text” means. Matthew is not taking the text for a spin that the original authors would not have recognized. Rather, their view was hazy because the fullness of time had not yet arrived. This does not mean that Matthew is finding things in the OT text not already there. Instead, the nature of their thereness transforms with the coming of Jesus.64 As Moo and Naselli state, “Does the OT intend the NT’s typological correspondence? We would answer ‘no’ if ‘intend’ means that the participants in the OT situation or the OT authors were always aware of the typological significance. On the other hand, we would answer ‘yes’ if ‘intend’ means that the OT has a ‘prophetic’ function.”65 These readings are not contradictory to the OT texts but truly retrospective readings. To put it another way, it is divinely intended but recognized retrospectively.

An example outside the Scriptures of how retrospective readings work may help here. Daniel James Brown’s best-selling book, The Boys in the Boat, tells the story of the Washington University crew team who won the gold under Hitler’s glaring eye. At the end of the book Brown reflects on what Hitler saw that day in 1936, connecting two events that could only be done so retrospectively. Brown says:

It occurred to me that when Hitler watched Joe and the boys fight their way back from the rear of the field to sweep ahead of Italy and Germany seventy-five years ago, he saw, but did not recognize, heralds of his doom. He could not have known that one day hundreds of thousands of boys just like them, boys who shared their essential nature—decent and unassuming, not privileged or favored by anything in particular, just loyal, committed, and perseverant—would return to Germany dressed in olive drab, hunting him down.66

Brown, as the narrator, brings two events into association: the day the Washington crew won the gold and the day when American soldiers invaded Germany. He acknowledges that Hitler could not have known, but he, as the author who stands on the other side of the war, sees the prefigurement of the American heart in the boys in the boat.

This is similar to Matthew’s method. Many of the Hebrew Scriptures are certainly prophetic, and Matthew sees them straining forward toward the messiah. However, other texts only shine after the messiah has come. Brown admits that Hitler could not have known what lay before his eyes, but now that the war is over, the two events can be held in simultaneity. This is true of all history. The whole truth concerning an event can only be known afterward, and sometimes only long after the event itself has taken place. The OT authors are not at fault for not knowing the future or how it will shape the events they are experiencing. If we believe that new events in history bring light and meaning to previous events, then how can we not also believe this for the coming of the Son of God? The apocalyptic coming of the messiah casts new light on old stories: the lamp of Jesus reveals corners that were dark and musty. Only after the fact of Jesus is Matthew able to see certain connections. So, like Brown, Matthew reads backward.

The process of reading and interpretation is a complex interplay between a retrospective and prospective reading. For example, if you read a detective novel and the key is revealed at the end, then all the hints in the first part come together. Suddenly the reader sees that the clues were present the whole time, but the key needed to be revealed. The early church described Jesus as the “key” of the Scriptures. Once the key is revealed, readers see the clues contained all along in Scripture. Retrospectively they seem patent; prospectively they seem more latent. The process of reading and interpreting Scripture is usually even more complex than a simple detective novel: once you reach a conclusion, it is hard to tell whether “the new” was discovered prospectively or retrospectively.

Other NT authors and indeed Jesus’s words on the road to Emmaus in Luke (where he interprets for them from “Moses and all the Prophets” all “the things concerning himself”; Luke 24:27) confirm this method. The new law stands over the old law and determines how we are to interpret the old law. This is because all of the NT authors read the Scriptures under the banner of Christ. Hugh of St. Victor says, “All of Divine Scripture is one book, and that one book is Christ.”67 Therefore, their exegesis of the OT is paradoxical, for though the authors viewed the Torah as authoritative, they also extended the text by pointing to its fundamental telos. The word spoken in the Torah was never meant to be self-referential but now dwells in Christ.68

Matthew’s language in chapter 13 supports this idea of reception and production. In one sense, according to the context of Matt. 13—and indeed the entire Gospel—this newness is not really “new.” These things have “been hidden since the foundation of the world” (13:35). Jesus is not changing God’s plan, for God has been slowly painting his canvas all along. At the same time, the revelation of these things through the Son is new. These are new/old truths, and the discipled scribe brings out a plate of goods for the benefit of others. According to Matthew, the message of the kingdom of heaven does not do away with the old but builds on top of it. Matthew shows his readers that in their enthusiasm for finding the new, they must not disregard the old. The old is not thrown away but brought out in fresh clothing. As Frederick Bruner says, “The new does not displace the old but accompanies it.”69

Yet at the same time, the order of the “new” and then the “old” in Matt. 13:52 is unexpected. It indicates that the old order is now to be interpreted in light of the new order.70 Augustine famously said, “The New Testament is latent in the Old, the Old patent in the New.”71 The difficulty comes in trying not to err on either side of this balance beam. Some of the richest reflections on the Scriptures come from exploring the connection between promise and fulfillment. Matthew demonstrates that to understand the Scriptures well, one must steady these two weights and see Jesus as the balance of it all. Therefore, Matthew gives his readers their first hermeneutical lesson in the form of a story about Jesus, not in a list of directives that can become a new law. Narrative resists tabulation and requires wrestling. An expansion of Augustine’s words puts it this way:

The New is in the Old contained,

The Old is in the New retained;

The New is in the Old concealed,

The Old is in the New revealed;

The New is in the Old enfolded,

The Old is in the New unfolded.72

Matthew is the discipled and trained scribe from Matt. 13:52 who learned wisdom from his teacher. More than maybe any other NT author, Matthew centers on the relationship between the new and the old. He summarizes the association through the word “fulfillment.”73 The First Evangelist teaches his readers his method in the writing of his Gospel, where readers find a complex yet consistent interchange between the new and the old.

This is not unlike the relationship of Jesus to the Hebrew Bible. Jesus is the singular candlelight that is best understood and seen through the reflection of thousands of surfaces in the Hebrew Bible. But in a similar way, without the candlelight, those surfaces are dark.74 Matthew unearths connections between the new and the old by reading both backward and forward. Sometimes he sees predictions about Jesus in the OT that are blatant, and other times he reconsiders nascent old texts in light of Jesus’s coming. He also is quite generous with his language. He does not simply look for word-for-word correspondences, but he uses his encyclopedic knowledge of Jewish beliefs and practices to construct his image of Jesus. At times he is explicit with these shadows; other times he is subtle. As a skillful scribe, Matthew goes in and out of these techniques, not always telling his reader which tactic he will use next. By so doing, he encourages his reader to engage and open their minds to the wonder of Jesus as the key not only to the OT but also to all of heaven and earth.

Where did Matthew get this method? Where is wisdom to be found? Who is responsible for this original, concrete, and even flexible exegesis? Although the typical answer hails and salutes either the early church, postmodern or modern theories, or early Jewish interpretation, it was C. H. Dodd who pushed further into this question. He said, “Creative thinking is rarely done by committees,” but individual minds usually originate creativity.75 Who was this originating mind? His answer: “The New Testament itself avers that it was Jesus Christ himself who first directed the minds of his followers to certain parts of the scriptures as those in which they might find illumination upon the mission and destiny.”76 God’s wisdom is found in Jesus the Son of God.

The early disciples rethought their OT because the origin of this rethinking came from Jesus, their teacher and sage. Matthew is discipled by the messiah. “Messianic exegesis—the interpretation of Scripture with reference to the messiah—is ultimately based on interpretation of Scripture by the messiah. Jesus, it appears, is his own best exegete.”77 My argument is that the best exegete, the most skilled rabbi, passed down these skills to his disciple: Matthew the scribe. Fulfillment, at its base level, is not so much a methodology as a presupposition,78 or even better, it is a presupposition, a conviction, which produces a methodology. I agree with France when he says, “I am not so sure that a neat distinction can be drawn between the hermeneutical technique and the theology of fulfillment which inspires it.”79

My plan is to trace the scribe’s writings through the contours of Matthew’s narrative, focusing on how he has the new interact with the old. Studies like this have tended to focus on the titles and the identity of Jesus and forget that much of what we learn about Jesus is from his role and function within the larger narrative. Therefore, for each subject I deal with, I will not simply be doing a word study but attempting to keep my ear close to the ground of Matthew’s narrative. I will allude back to the section on Matthew’s method simply to point out more specific examples of shadow stories, history unified, reception and production, and apocalyptic-messianic fulfillment. The best methods are supported with evidence, not simply asserted.

1. While there are some excellent resources on Matthew’s use of the OT (including Beale and Carson, New Testament Use of the Old), few attempt to integrate the interpretative stance of each author. Beale himself notes this weakness. The work “did not attempt to synthesize the results of each contributor’s interpretative work on the use of the OT in the NT. Consequently, the unifying threads of the NT arising out of the use of the OT are not analyzed and discussed.” Beale, New Testament Biblical Theology, 13. A notable exception is Richard Hays (Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels) in his work on the Gospels.

2. Esther Juce (“Wisdom in Matthew,” 135) says, “Jesus is seen as the consummate law-giver, the consummate prophet, and the consummate sage, thus completely fulfilling the Hebrew scriptural tradition in all of its three aspects.”

3. Some might object that I am losing the wisdom trail here with the statement about the Law and the Prophets. However, as noted earlier, many are now seeing wisdom less as a genre and more as a characteristic like righteousness or holiness. In addition, Longman notes how many of the teachings of the Proverbs, Wisdom of Solomon, and Ben Sira connect wisdom and law. For example, the command to honor your father and mother is echoed in Prov. 1:8; 4:1, 10; 10:1; 13:1, while the command not to bear false witness is echoed in 3:30; 6:18, 19; 10:18; 12:17, 19. Longman (Fear of the Lord Is Wisdom, 11, 163–75) argues that wisdom, law, and covenant are more closely associated than many realize (cf. Sib. Or. 5.357; Sir. 23:27; Wis. 9:9; Bar 3:37–4:1; 2 Bar. 5.3–7; 38.2; 77.16).

4. Matthew employs a fulfillment quotation twelve times, compared to Mark’s one use and Luke’s double use.

5. France (Gospel of Matthew, 10) argues that the central theme of Matthew’s Gospel is fulfillment. Brandon Crowe (“Fulfillment in Matthew”) argues for eschatological reversal; James Hamilton (“‘The Virgin Will Conceive’”) argues for typological fulfillment; Daniel Kirk (“Conceptualising Fulfilment in Matthew”) goes the lexical route and defines it as “to fill up, to complete, to perfect.” Carson (“Christological Ambiguities,” 99) speaks of fulfillment in that “laws, institutions, and past redemptive events have a major prophetic function in pointing the way to their . . . culmination in Jesus.” Turner (Matthew, 25) argues that fulfillment in Matthew “includes ethical, historical, and prophetic connections. . . . By recapitulating these biblical events, Jesus demonstrates the providence of God in fulfilling his promises to Israel.”

6. Moule, “Fulfilment-Words in the New Testament,” 301.

7. Bruner, Christbook, 33; Turner, Matthew, 25. France (Gospel of Matthew, 12) agrees: “Fulfillment for Matthew seems to operate at many levels, embracing much more of the pattern of OT history and language than merely its prophetic predictions.”

8. Hays, Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels, 186.

9. Hays, Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels, 186.

10. Pennington, review of Hidden but Now Revealed.

11. Hays (Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels, 186) rightly asserts, “For Matthew, Israel’s Scripture constitutes the symbolic world in which both his characters and his readers live and move. The story of God’s dealings with Israel is a comprehensive matrix out of which Matthew’s Gospel narrative emerges. The fulfillment quotations, therefore, invite the reader to enter an ongoing exploration of the way in which the law and the prophets in their entirety find fulfillment (Matt. 5:17) in Jesus and in the kingdom of heaven.”

12. Pennington, review of Hidden but Now Revealed.

13. Fulfillment is both a method and a conviction, but it can be helpful to put different terms on what Matthew is doing so that categories can be more clearly divided. As Aquinas says, Jesus fulfilled the law in five ways: (1) by fulfilling the things prefigured in the law (Luke 22:37); (2) by fulfilling its legal prescriptions to the letter (Gal. 4:4); (3) by doing works through grace, through the Holy Spirit, which the law was unable to do in us (Rom. 8:3–4); (4) by providing satisfaction for the sins by which we were transgressors of the law, and when the transgressions were taken away, he fulfilled the law (Rom. 3:25); (5) by applying certain perfections to the law, which were either about the understanding of the law or for a greater perfection of righteousness/justice (Heb. 7:19; confirmed by Matt. 5:48). See Aquinas, Commentary on Matthew.

14. Huizenga (New Isaac, 19) notes that the lure of the formula quotations in Matthew has left the more covert allusions less examined.

15. As in 21:4. While the quotations in 2:5–6 and 13:14–15 have also been considered under this category, at this stage it is important simply to look at the ones introduced by a formula.

16. Menken, “Messianic Interpretations.”

17. Menken, “Messianic Interpretations,” 486.

18. Menken, “Messianic Interpretations,” 485.

19. See a similar point in Hays, Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels, 106.

20. Although these are theologically loaded terms that many in biblical studies might attribute to the early church, this is a propensity that stems from Kantian and Enlightenment thinking. As Matthew clarifies earlier Jewish hopes, so too early church developments clarify and define Christology.

21. See Crisp, The Word Enfleshed; Allison, Constructing Jesus, 31–43.

22. Macaskill (Revealed Wisdom) argues for the mutual presence of sapiential and apocalyptic elements in Judaism and early Christianity.

23. Hagner, “Apocalyptic Motifs,” 60. He also states that an apocalyptic perspective “holds a much more prominent place than in any of the other Gospels” (53).

24. Orton, Understanding Scribe, 167–68.

25. Orton (Understanding Scribe, 175) asserts, “We hope to have demonstrated that Matthew in some essential respects—in his sense of vested authority and mission, in his apocalyptic understanding of scripture and in his insight into the essence of Jesus’ instruction in understanding the mysteries of the kingdom and the will of God for the righteous—sees Jesus, the church and himself standing squarely in the tradition of the prophets and in the quasi-prophetic tradition of the apocalyptic scribes.”

26. While I don’t follow “apocalyptic theology” or its adherents in their proposal for radical disjointedness, a view that trims the sharp edges from their thought is on target.

27. I deal more with this text in the chapter on Moses, where I discuss the parallels of “yoke” with the wisdom tradition.

28. For a more detailed analysis, see Walter Wilson, “Works of Wisdom.”

29. Wisdom 8:21 says, “But I perceived that I would not possess wisdom unless God gave her to me” (NRSV).

30. Dryden argues this in Hermeneutic of Wisdom.

31. Witherington, Jesus the Sage, 155–56.

32. Witherington, Jesus the Sage, 158–59.

33. I acknowledge that this method is not popular in biblical studies, but either we approach the Gospels with suspicion, or we approach them with trust. As J. Charlesworth (“From Messianology to Christology,” 35) claims, “The gospel and Paul must not be read as if they are reliable sources for pre-70 Jewish beliefs in the Messiah.” It is fine for historians to examine sources and compare them and respect their historical placement, but this is also a view of history that fails to see how later writings can shed light and new meaning on earlier writings.

34. Wright, New Testament and the People of God, 310.

35. Throughout this work, I will argue that while Davies’s proposal is right, Matthew’s portrayal of the messiah is also more expansive than this. He defines Jesus the Messiah around Moses and around Israel as well.

36. W. Davies, “Jewish Sources of Matthew’s Messianism,” 511: “His messianism, in short, is a corrective messianism, corrective of excesses and illusions, even as it recognizes ethnic privacy (or particularity) and at the same time affirms universalism.” While I disagree with Davies that we can precisely identify the nature of the dark side of the Matthean communities’ hope, I argue that Matthew is providing some sort of corrective, and this corrective is best found in how Matthew defines and redefines messianic hope.

37. Wright, Resurrection of the Son of God, 554–55.

38. I first heard this metaphor from Sailhamer, “Messiah and the Hebrew Bible,” 14.

39. For more on this distinction, see Levering, Participatory Biblical Exegesis.

40. Jenson, “Scripture’s Authority in the Church,” 35.

41. Schreiner, Body of Jesus.

42. Frye, The Great Code, 208.

43. Boersma and Levering, “Spiritual Interpretation and Realigned Temporality,” 590.

44. Burridge, What Are the Gospels?

45. I was made aware of this reference by Dryden, Hermeneutic of Wisdom, 100.

46. Plutarch, Alexander 1.1–2, in Lives, trans. B. Perrin, LCL 99, 7:225.

47. Alexander, “What Is a Gospel?”

48. For more on the development of the use of this term from oral to written, see Pennington, Reading the Gospels Wisely, 13–16, and esp. 6–10: “From ‘Oral Gospel’ to ‘Written Gospel,’” in chap. 1.

49. About the larger context of Isa. 40–66, Pennington says: “Isaiah describes it [the gospel] with a full artist’s palette of vibrant colors. It is comfort and tenderness from God (40:1, 2, 11; 51:5; 52:9; 54:7–8; 55:7; 61:2–3), the presence of God himself (41:10; 43:5; 45:14; 52:12), help for the poor and needy (40:29–31; 41:17; 55:1–2), the renewing of all things (42:9–10; 43:18–19; 48:6; 65:17; 66:22), the judgment of God’s enemies (42:13–17; 47:1–15; 49:22–26; 66:15–17, 24), the healing of blindness and deafness (42:18; 43:8–10), the forgiving of sins (44:22; 53:4–6, 10–12), and the making of a covenant (41:6; 49:8; 55:3; 59:21).” Pennington, Reading the Gospels Wisely, 15–16.

50. Dryden, Hermeneutic of Wisdom, 123.

51. Hays (Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul, 14) popularized the term “intertextuality.” Some debate whether biblical scholars should be using this term at all unless they adhere to the reader-oriented approaches. See Kristeva, Desire in Language; Kristeva and Roudiez, Revolution in Poetic Language; Bakhtin, Dialogic Imagination. Fishbane prefers the term “inner-biblical exegesis.” See Fishbane, “Revelation and Tradition”; Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel.

52. Another way to categorize the relationship between the new and the old is summarized by Moo and Naselli (“Use of the Old Testament,” 736–37), whose argument is not far from what I have proposed. They are looking at the entire canon and assert the following: (1) A canonical approach provides the interpretive framework by answering the “why” question. (2) Typology describes one critical way in which the two Testaments within one canon can be seen to relate to each other—the “how.” And (3) sensus plenior is the “what”: the fuller or deeper sense that NT writers find in OT texts as they read canonically. The NT authors discern a “fuller” meaning in OT passages by placing those texts in a wider context than the original authors could have known.

53. I picked up this term from Senior, “Lure of the Formula Quotations,” 115. When I say I will use the term, this does not mean I won’t use typology or figural interpretation as well for the sake of variety.

54. Hays (Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels, 106) overstates it when he says Matthew leaves nothing to chance in his OT references.

55. The nature of the people seeing only the explicit references may be tied to the tunnel vision I spoke of earlier.

56. Allison, New Moses, 284.

57. Leithart (Jesus as Israel, 77–78) claims from this use of Nazareth that Matthew “also indicates that we need to read poetically, even punningly, if we are going to understand how Jesus fulfills the prophets. He does not always fulfill prophecy in a straightforward, literal manner.”

58. This language of “surface meaning” and “bonus meaning” is adopted from France, “Formula-Quotations of Matthew 2.” Consider the example of formula quotations: only one of the formula quotations exactly repeats the text of the LXX. In most cases Matthew’s quotation seems to be a creative yet faithful rendering of the passage, adapting the text to more clearly point out how Jesus’s life completes the OT story (see Matt. 27:9–10 and Zech. 11:12–13). A study of only the explicit OT predictions merely scratches the surface. Matthew’s concept is far broader and more complex.

59. France, Matthew: Evangelist and Teacher, 183.

60. This language comes from Allison, New Moses, 285.

61. Orton, Understanding Scribe, 174.

62. See Alkier, “Intertextuality and the Semiotics” and “Categorical Semiotics.”

63. Kaiser, “Lord’s Anointed.”

64. As Sequeira (“Eschatological Fulfillment in Christ,” 5) says, “Although the author’s use of a text may transcend its original meaning, it is always a legitimate outgrowth of this original meaning.”

65. Moo and Naselli, “Use of the Old Testament,” 727–28.

66. D. Brown, Boys in the Boat, 368.

67. As quoted in Billings, Word of God for the People, 166.

68. Yet the Torah also points forward to Jesus. In Jesus’s ministry, he constantly asks, “Have you not read?” “Do you not see?” “Have you not understood?” Perhaps the best way to put it is in Matthew’s explicit language: “Do not think I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them” (5:17). Matthew’s strategy of reading shows us how he sees the new and the old interacting in complex ways, but the new seizes priority and reinterprets (or clarifies) the old while, at the same time, the old informs the new. Both of these statements must be held in tension, something Matthew does throughout his Gospel.

69. Bruner, Churchbook, 56.

70. See Matt. 9:16–17; 2 Cor. 5:17; Heb. 8:13; and 1 John 2:7 for other references where the new is mentioned before the old.

71. Augustine, Quaestiones in Heptateuchum 2.73. The Latin is “quamquam et in Vetere Novum lateat, et in Novo Vetus pateat,” which could also be translated “The New Testament in the Old lies concealed, the Old in the New is revealed.”

72. Augustine, Quaestiones in Heptateuchum 2.73.

73. This chapter has focused more on theory, while the following chapters will examine how this theory is put to use in the different pictures of the messiah.

74. Like all analogies, this one breaks down at certain points. In one sense the Hebrew Bible produced its own light, which pointed to the greater light.

75. Dodd, According to the Scriptures, 109–10.

76. Dodd, According to the Scriptures, 110.

77. Knowles, “Scripture, History, Messiah,” 69–70.

78. Saying that fulfillment is more of a presupposition than a method does not mean principles can’t be garnered from what Matthew and other NT authors do. But that it is a presupposition also explains why so many people argue about which “methodology” and description is actually the correct one. This probably proves that we try too hard to fit these ideas into neat modern boxes rather than being comfortable with some fluidity.

79. France, Matthew: Evangelist and Teacher, 182.