![]()

Why don’t we get the results we want from other people? Husbands and wives routinely complain about their spouses expecting them to be mind readers. Managers bemoan employees’ failures to perform as expected, often saying, “But I told him once.” Most managers’ ideas about training omit a feedback loop to ascertain comprehension and acceptance, and ignore the need for perpetual reinforcement. Everywhere you look in human-to-human communication, there is disappointment. This certainly exists for marketers, too, although many business owners don’t think they should be able to outright control the behavior of their customers to the extent they should be able to employees, vendors, or family members. In marketing and sales, control is exactly what we need. Ultimately, all this is much about simple clarity. Do people really, clearly know what is expected of them? Or are you taking too much for granted, chalking things up as too obvious to bother clarifying?

You Will Give Clear Instructions

Most people do a reasonably good job of following directions. For the most part, they stop on red and go on green, stand in the lines they’re told to stand in, fill out the forms they’re given to fill out, applaud when the Applause sign comes on. Most people are well-conditioned from infancy, in every environment, to do as they are told.

Most marketers’ failures and disappointments result from giving confusing directions or no directions at all. Confused or uncertain consumers do nothing. And people rarely buy anything of consequence without being asked.

When I held one of my mastermind meetings for one of my client groups at Disney, one of the Disney Imagineers we met was in charge of “fixing confusion.” At any spot in any of the parks where there was a noticeable slowing of movement (yes, they monitor that) or an inordinate number of guests asking employees for directions, he was tasked with figuring out the reason for the confusion and changing or creating signs, giving buildings more descriptive names, and even rerouting traffic as need be to fix the confusion. “It isn’t just about efficient movement,” he told us, “it’s about a pleasing experience. People do not like not knowing where to go or even what is expected of them.”

In-store signage, restaurant menus, icons on websites—everywhere you closely examine physical selling environments and media—you will find plenty of assumptions made about the knowledge people have (and may not have) and plenty of opportunity for confusion. In a split test in nonprofit fundraising by direct mail, four different business-reply envelopes were used. One was a standard pre-paid business reply envelope with the standard markings. The second was the same, but with a large hand-scrawl-appearing note, “No postage stamp needed. We’ve paid the postage. Just drop in the mail.” Third was a plain, pre-addressed envelope with an actual stamp affixed. Fourth was the plain, pre-addressed envelope with an actual stamp affixed, plus the hand-scrawl-appearing note, “No postage stamp needed. We’ve paid the postage. Just drop in the mail.” To be fair, the last two add obligation to clarity, and they were the winners by significant margin. But the first envelope was the biggest loser by a very big margin, even against the second, simply because the first presumes knowledge on the consumer’s part that is not there. Not long ago, I got a statistically meaningful increase in conversion of visitors to buyers at a website by switching from just a “Buy Now” button to the button, plus the words “Click This Button to Buy Now.”

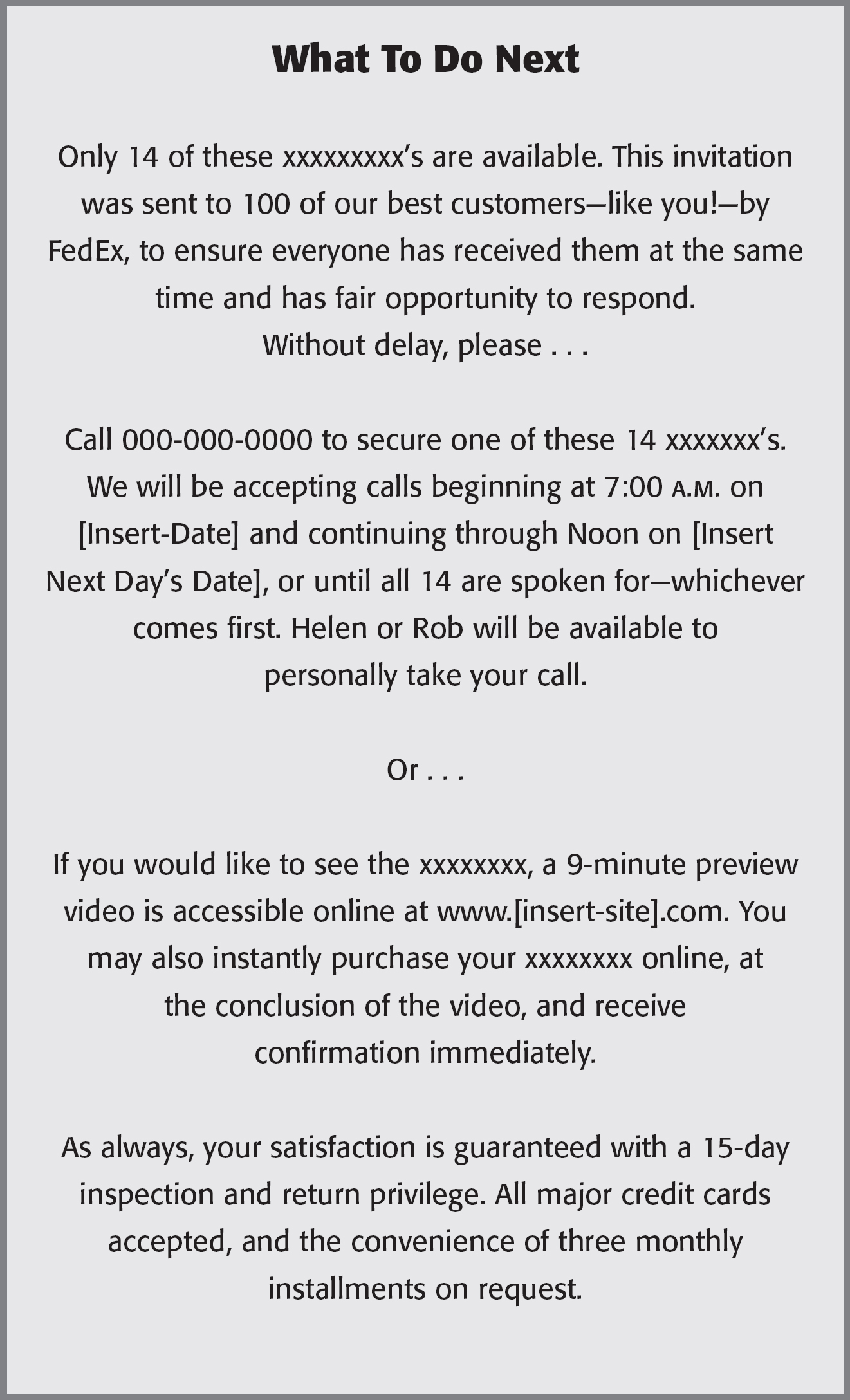

When you put together any marketing tool, ad, flier, sales letter, website, phone script, etc., or any physical selling environment, it should be carefully examined for presumption of knowledge on the consumer’s part, for lack of clarity about what is expected of them, or for wimpiness about asking clearly and directly for the desired action. Stop sending out anything without clear instructions. As illustration, take a look at Figure 3.1 on page 34, excerpted from an actual sales letter (sent to knowledgeable buyers already in a relationship with the marketer). Note that the subhead above the copy is quite clear.

It’s also worth noting that people’s anxiety goes up anytime they are asked to do something but are unsure of what to expect. In my book No B.S. Guide to Marketing to Leading-Edge Boomers and Seniors, in Chapter 15 (“The Power of Stress Reduction”), I share an example of a marketing device and copy we routinely use with professional practices, such as chiropractic, dental, medical, financial advisors’, or lawyers’ offices titled “What to Expect at Your First Appointment.” Anxiety about anything uncertain grows more acute with age, but is not unique to boomers and seniors. Removing it with very clear instructions, directions, descriptions, or information is a smart strategy.

Last, you should consider the physical device of the order form. The late, great direct-response copywriter Gary Halbert claimed to often spend as much time on the copy and layout of the order form as he did the entire sales letter. In one part of my business life, professional speaking and selling my resources in an in-speech commercial, I’ve taken great pains to create order forms passed out to the audiences, or at the rear-of-room product tables, that mimic the best mail-order order forms in completeness and clarity, and I credit my order forms with aiding me in consistently achieving exceptional results—including selling over $1 million of my resources from the stage per year, for more than ten years running. A lot of businesses don’t even use order forms when they could and should.

The Clearer the Marching Orders, the Happier the Customer

In direct marketing, we have learned a lot about consumer satisfaction, which affects refunds in our world and at least repeat purchasing and positive or negative word-of-mouth in every business. Presented with “difficult” or complex products, many customers are quickly, and profoundly, unhappy. I cannot tell you the number of times I’ve received a product that disappointed by seeming to be more trouble than it’s worth, and returned it or simply trashed it, and I am not alone. A friend of mine, often an early adopter, took her first iPad back to the store to ask for help and was told by a disdainful clerk, “It’s intuitive.” Not to her. In direct-to-consumer delivery of complex products, we often add written labels to CDs or DVDs very clearly stating: Read/Listen/Watch This First. We sometimes even decal the outside of a box with “Call This Free Recorded Message, Please, BEFORE You Open & Unpack Your <Insert Product Name>.” We include a simple flow chart or “map” of how to use the product. Often, we have to “sell” the tolerance for complexity. One of my clients, Guthy-Renker, has the number-one acne treatment brand, Proactiv®, sold and delivered direct to the consumer. Although it’s made clear in the advertising, a chief cause of consumer dissatisfaction and noncompliant use has always been that there are three bottles and a three-step process. Three. To many, two steps too many. If we don’t convince them that this is necessary and worth it, the product comes back for refund. You may not have actual refunds occurring, but more quiet dissatisfaction can be just as damaging.

Consumers like, are reassured by, and respond to clarity. Be sure you provide it.

Figure 3.1 on page 34 is actual “directions copy” from a sales letter, with the business identity removed. It has reinforced the scarcity/urgency established earlier in the letter. It includes the offer-specific phone number, times to call, and persons with whom they’ll be speaking, as well as an alternative route to the website. In previous campaigns, this marketer had used a much simpler instruction—essentially “Call 000-000-0000 to place your order.” The copy on page 34 more than tripled the response vs. the previously used instructions.

FIGURE 3.1: Sales Letter