1 Structure of the Abdominal and Pelvic Cavities: Overview

1.1 Architecture, Wall Structure, and Functional Aspects

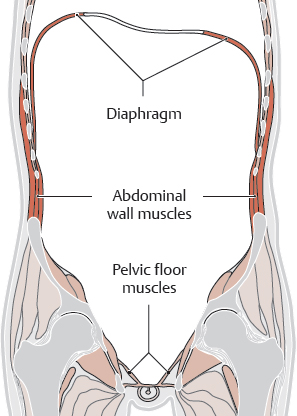

A Architecture and wall structure of the abdominal and pelvic cavities

Whereas the thoracic and abdominal cavities are separated by the diaphragm, the abdominal and pelvic cavities are continuous with each other. They are divided topographically by the linea terminalis. Thus, they form a single functional unit (see p. 2). Bones (vertebral column, thorax, and pelvis) as well as muscles (diaphragm, abdominal, and pelvic floor muscles) along with their fasciae and aponeuroses form the walls of this space. It is bounded by the following structures:

• Superiorly (see Ca): diaphragm with right and left domes and central tendon

• Inferiorly (see Cb): bony pelvis, muscles of the pelvic wall (iliacus, obturator internus, piriformis, and coccygeus) and pelvic floor muscles (mainly the levator ani forming most of the pelvic diaphragm)

• Posteriorly (see Cc): lumbar vertebral column, deep muscles of the abdominal wall (quadratus lumborum and psoas major), and intrinsic back muscles

• Anteriorly and laterally (see Cd): anterior and lateral muscles of the abdominal wall together with their aponeuroses (rectus abdominis and transversus abdominis as well as internal and external abdominal obliques)

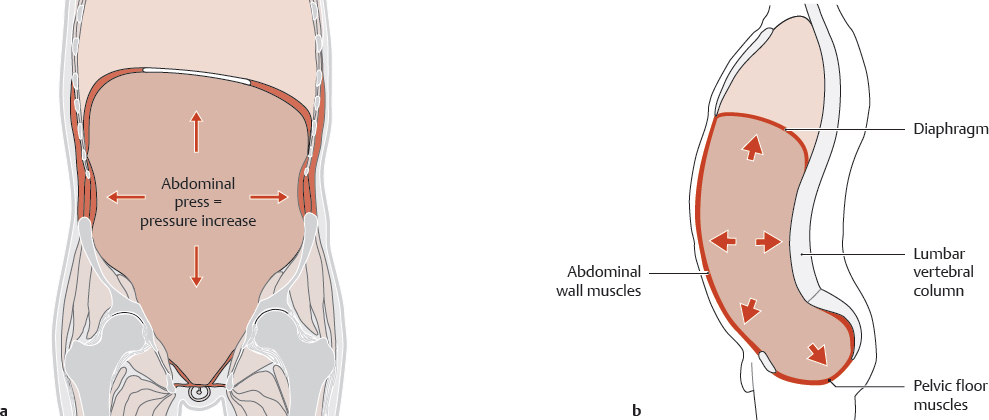

B Functional aspects of abdominal and pelvic wall structure: abdominal press

Abdominal press is made possible by the structure of the abdominal and pelvic walls, which plays an important role in their elastic properties. “Abdominal press” describes the voluntary contraction of the diaphragm, and abdominal and pelvic muscles. When the muscles contract they reduce the volume of the abdominal cavity thereby significantly raising the intra-abdominal pressure: pressure in the standing position is approximately 1.7 kPa (2.75 mmHg), when lying down it is approximately 0.2 kPa (1.5 mmHg), and under strain including coughing or squeezing it is 10–20 kPa (75–150 mmHg).

Abdominal press is important in

• Emptying of the rectum (defecation), of the bladder (micturition), and of the stomach (vomiting),

• Uterine contractions during the expulsive phase of labor (“expulsive pains”),

• Stabilizing the spinal column (mainly the lumbar spine) and the trunk (the wall stiffens like the wall of an inflated ball), for example when lifting heavy loads, but also in the standing posture (hydrostatic effect of abdominal press).

Hernias occur when the pressure load is greater than the strength of the complex myofascial network. They develop either in the anterior abdominal wall or more commonly in the groin region because the weight of the pelvic and abdominal organs puts increasing strain on the wall structures, which increases from superior to inferior. Additionally, the pelvic floor muscles in particular are much less able to withstand the increased abdominal pressure than the abdominal wall muscles or the diaphragm. During abdominal press, closure of the glottis and the retaining of air in the lungs gives support to the diaphragm; there is no such compensatory mechanism in the pelvic floor muscles making it a characteristic weak spot. After excessive stretching (e.g., caused by vaginal delivery) the pelvic floor is unable to maintain the pelvic organs in their normal position (pelvic floor descent) and provides inadequate support for the abdominal press. The results are urinary and fecal incontinence.

C Boundaries of the abdominal and pelvic cavities

a Diaphragm, inferior view; b Pelvic floor, superior view; c (d) Anterior (posterior) view of the posterior (anterior) trunk wall.

1.2 Divisions of the Abdominal and Pelvic Cavities

A Midsagittal section through the abdomen and pelvis, viewed from the left side

B Divisions of the pelvic and abdominal cavities

Each column of diagrams shows a midsagittal section viewed from the left side, as well as two axial sections, one at the L1 level and the other at the lower part of the sacrum, both viewed from below.

a–c Topography of body cavities: abdominal cavity and pelvic cavity (imaginary line separating the two cavities is the linea terminalis);

d–f Serous cavities (peritoneal spaces): abdominal peritoneal cavity and pelvic peritoneal cavity;

g–i Connective tissue spaces (extraperitoneal spaces): retroperitoneal space and subperitoneal space; serous cavities and extraperitoneal spaces are separated by peritoneum (see p. 209).

1.3 Classification of Internal Organs Based on their Relationship to the Abdominal and Pelvic Cavities

The organs of the abdomen and pelvis can be classified according to various topographical criteria:

• By layers in the anteroposterior direction (A)

• By levels in the craniocaudal direction (B)

• As intra- or extraperitoneal based on their peritoneal investment (C, D)

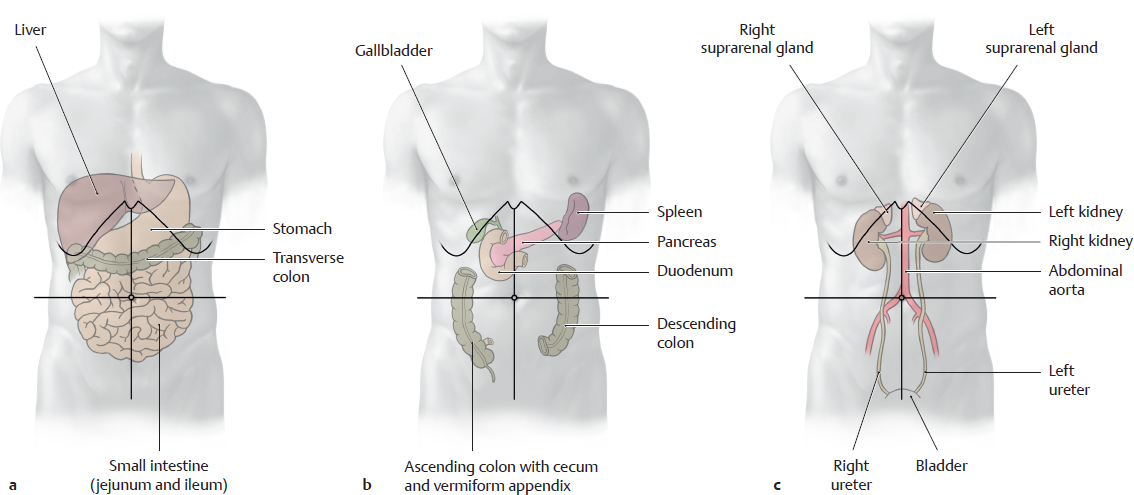

A Classification of the abdominal and pelvic organs by layers

The abdominal and pelvic organs can be roughly divided into three layers in the anteroposterior direction. This classification is particularly useful from a surgical standpoint.

Note: Larger organs may occupy more than one layer (see p. 206).

a Anterior layer: liver, stomach, transverse colon, jejunum, ileum, and bladder (for clarity not shown here, but shown with the other urinary organs in c);

b Middle layer: liver, duodenum, pancreas, spleen, ascending and descending colon, and uterus (not shown for clarity, extends into the anterior layer);

c Posterior layer: great vessels, kidneys, ureters, and suprarenal glands (for clarity, the bladder is shown in its relationship to the other urinary organs, see a).

B Classification of the abdominal and pelvic organs by levels

In this classification the organs are roughly assigned to craniocaudal levels based on their relationship to the transverse mesocolon (upper and lower abdominal organs) and lesser pelvis (pelvic organs). Because the kidneys and suprarenal glands are retroperitoneal, they are not listed in the table. When the kidney is projected onto the abdominal wall, its inferior pole extends into the lower abdomen.

Level |

Organs located there |

• Upper abdomen

(above the transverse mesocolon) |

• Stomach

• Duodenum

• Liver

• Gallbladder and biliary tract

• Spleen

• Pancreas |

• Lower abdomen

(between the transverse mesocolon and pelvic inlet plane) |

• Jejunum and ileum

• Cecum and parts of the colon

Note: The transverse colon, while located in the upper abdomen, is classified functionally as part of the lower abdomen. |

• Lesser pelvis |

• Bladder

• Terminal portion of ureter

• Rectum

• Uterus, uterine tube, ovary, and vagina

• Portions of the ductus deferens, prostate, and seminal vesicle (the testis and epididymis are outside the pelvic cavity) |

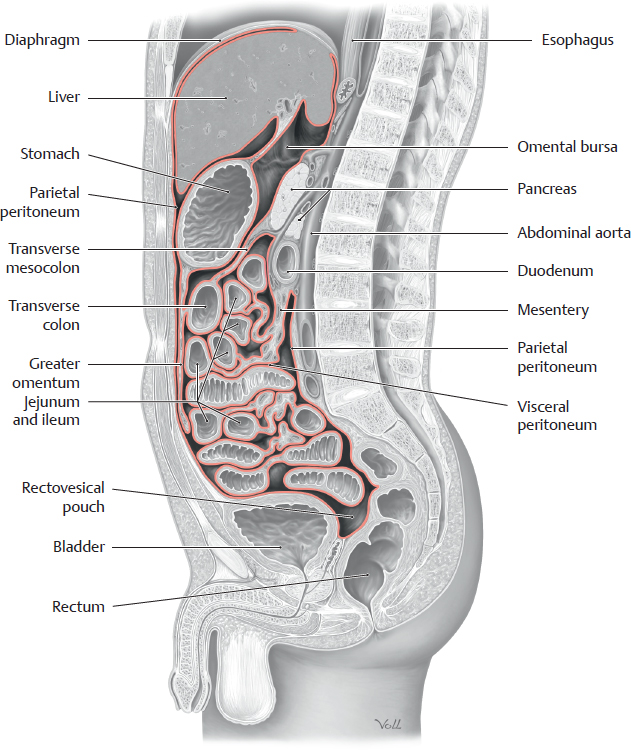

C Location of intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal organs in the abdomen and pelvis

Midsagittal section (kidneys outside the sectional plane) viewed from the left side.

The peritoneal cavity is a closed cavity that is lined by peritoneum and surrounded on all sides by the extraperitoneal cavity. Laterally, anteriorly and superiorly, the extraperitoneal cavity appears like a very narrow slit (see p. 207). Only its posterior portion (retroperitoneal space) and inferior portion (extraperitoneal space of the pelvis) are true spaces that contain organs. Because peritoneum covers the organs (visceral peritoneum) and walls (parietal peritoneum), the intraperitoneal organs can easily glide upon one another. The extraperitoneal organs, such as the bladder or rectum are not, or are only partially, covered by peritoneum. The bladder is covered by peritoneum only on one side (on its superior surface), which enables it to expand upward as it becomes distended with urine. This part of the peritoneum, which in females also covers large parts of the uterus, is known as urogenital peritoneum.

The mesentery is a band of connective tissue (a suspensory ligament also referred to as “meso”), which is also covered by peritoneum–by parietal peritoneum near where the mesentery is attached to the body wall and by visceral peritoneum near where it is attached to the organs. The mesentery contains the neurovascular structures of the intraperitoneal organs that are “suspended” from it. This suspensory ligament allows the intraperitoneal organs to have greater mobility than extraperitoneal organs, which are embedded in the connective tissue of the wall of the peritoneal cavity, either primarily because they were retroperitoneal when they formed or secondarily because they “migrated” behind the peritoneum during the course of embryonic development (see D and p. 47).

D Intra- and extraperitoneal organs of the abdomen and pelvis

Location in relation to the peritoneum |

Organs |

Intraperitoneal

(Organs are completely covered by peritoneum and are suspended by mesentery) |

|

• In the abdominal peritoneal cavity |

• Stomach, spleen, liver and gallbladder, small intestine (parts of the superior and ascending duodenum plus jejunum and ileum), transverse and sigmoid colon, cecum (portions of variable size may be extraperitoneal, see below) |

• In the pelvic peritoneal cavity |

• Fundus and body of the uterus, the ovaries, and the uterine tubes and possibly the superior portion of the rectum |

Extraperitoneal

(Organs without a mesentery; their neurovascular structures are located in the extraperitoneal connective tissue) |

|

Primarily extraperitoneal (extraperitoneal from the outset) |

|

• Behind the abdominal or pelvic peritoneal cavity, thus retroperitoneal

• Below the pelvic peritoneal cavity, thus infra- or subperitoneal

Secondarily extraperitoneal (become extraperitoneal during the course of embryonic development; the organs are covered by peritoneum anteriorly) |

• Kidneys, suprarenal glands, ureters

• Urinary bladder, prostate, seminal vesicle, uterine cervix, vagina, and rectum past the sacral flexure (the urinary bladder is covered by peritoneum superiorly [urogenital peritoneum]) |

• Behind the abdominal or pelvic peritoneal cavities, thus retroperitoneal |

• Small intestine (duodenum: descending, horizontal, and part of the ascending portions), pancreas, ascending and descending colons, parts of the cecum (see above), rectum up to the sacral flexure |