CHAPTER 3

‘Productive’ Sites and the Pattern of Coin Loss in England, 600–1180

Mark Blackburn

The evidence for coin circulation in Early Medieval England has changed out of all recognition over the past twenty years. With the advent of the hobby of metal-detecting in the early 1970s, and its dramatic growth in the 1980s and 1990s, new data on coin single-finds was amassed on a scale never seen before. The timing was fortuitous, for Metcalf had already begun studying find distributions as a means of identifying the origin and circulation patterns of the early eighthcentury pennies (the so-called ‘sceattas’) (Metcalf and Walker 1967; Metcalf 1974), and he took pleasure in publishing individual new finds at length as they were still something of a novelty (e.g. Metcalf 1976 and 1984b). As the numbers swelled and numismatists developed their contacts with the detecting community, the recording and publication of finds was put on a more systematic footing in the British Numismatic Journal, initially through a series of articles (Blackburn and Bonser 1984a; 1985; 1986) which in 1987 were subsumed into the annual ‘Coin Register’. Several surveys of the find evidence from a particular period or region appeared (e.g. Rigold 1975; Rigold and Metcalf 1977 and 1984; Pirie 1986b and 2000; Blackburn 1993b; Bonser 1998; Metcalf 1998a), but they quickly became out-of-date and one could not readily be compared with another. Since 1999 an on-line Corpus of Early Medieval Coin Finds from the British Isles, 410–1180 (EMC: via medievalcoins.org) has provided greater access to this material.

It soon emerged that the finds, far from being evenly spread across the country, displayed a regional bias towards the eastern and southeastern counties, and within those areas there were dramatic hot-spots – with certain fields yielding remarkable quantities of Anglo-Saxon coins and metalwork. The finds from two such sites were published in the 1980s – ‘Sancton’ (=Newbald, Yorks.) (Booth and Blowers 1983) and ‘Near Royston’, Herts. (Blackburn and Bonser 1986, 65–80) – and these could be compared with the equally prolific excavation finds from Hamwic (Southampton) (Metcalf 1988a). In 1989 a conference of numismatists and archaeologists organised in Oxford by Metcalf and myself considered the phenomenon of ‘productive’ sites, as these had by then become known, but regrettably the proceedings were not published. The term ‘productive’ site has always been problematic, for it was clear from the start that one could not make comparisons between sites simply on the basis of the number of coins found, as this depended so much on the area available for investigation and the opportunity and conditions of recovery. It is, however, helpful to distinguish fields that simply have little if any coinage or metalwork on them, from ones where there clearly was a considerable amount in the ground waiting to be recovered. It is true that the productive status of some sites only emerges very slowly as more finds are made, and that there is a graduation from sites that yield nothing to ones that are very prolific. Yet once recognised as ‘productive’ it highlights an aspect of the site that demands interpretation. That is not to say that a similar explanation will stand for all ‘productive’ sites, despite the temptation to regard them as the probable location of a market or occasional fair, for already we can see that they occur in a range of contexts: in urban and rural settlements, monastic sites, by rivers, roads and Roman forts.

The principal ‘productive’ sites are listed in the Appendix and their distribution mainly in the eastern counties of England is shown in Fig. 3.1. Many of the finds have been published or are accessible from the web, but in only a few cases have they been discussed as site assemblages. Those reports should appear soon. The purpose of this paper is to consider the finds from a number of representative sites and set these in a context of the general pattern of finds across England. Before doing so, it is necessary to look at the theory of coin-find evidence and different approaches to its analysis.

FIGURE 3.1. Map of the principal ‘productive’ sites in Britain (see Appendix). 1. Hamwic; 2. ‘Near Carisbrooke’ 3. Hollingbourne; 4.‘Near Canterbury’ 5. Reculver; 6. Tilbury; 7. London; 8. Ipswich; 9. Coddenham; 10. Caistor by Norwich; 11. Thetford; 12. Barham; 13. ‘Near Cambridge’; 14. ‘Near Royston’; 15. Bedford; 16. Bidford-on-Avon; 17. Bawsey; 18. ‘South Lincolnshire’; 19. Lincoln; 20. Torksey; 21. Flixborough; 22. West Ravendale; 23. Riby; 24. South Newbold; 25. York; 26. Cottam; 27–8. ‘Near Malton’ 1 and 2; 29. Whitby; 30. Carlisle; 31. Whithorn.

The different nature of hoard and single-find evidence

There is a fundamental difference between the evidence provided by coin hoards and single-finds:

Hoards

Hoards are typically sums of money that have been put together and buried for safe keeping, and then for some reason not recovered by the owner. The coins may have been selected for the purpose and may not be representative of the money in circulation. Hoarding was a normal way of protecting money, but it may have been more intense in times of trouble or economic pressure, although these could also lead to the digging up of older hoards. What most affects the pattern of surviving coin hoards is the circumstances that led them not to be recovered by the owners or their families. The non-recovery of hoards may have increased, for example, when there was political turmoil, especially war, if people were killed or taken away from their homes. But that is by no means the only situation and it is wrong to seek a political context for every hoard discovered. There are also different categories of hoards – currency hoards, savings hoards, hoards with double peaks, grave deposits – each of which will influence the final composition of the hoard (Grierson 1975, 124–39). Hoards are the numismatist’s primary tool for determining the chronology of a coin series and how long particular coin types remained in circulation.

Single-finds

Single-finds are assumed for the most part to be individual accidental losses from the money in circulation. They will have been lost in many different ways, some while changing hands in a transaction, others slipping from people’s purses or pockets or having been dropped during a fight. Whatever the means, they should be a random sample of the coins in circulation, not specially selected because of their weight, fineness or coin type. Their chance of loss should not have been affected by political events as it was with hoards, so they ought to reflect genuine patterns of coin circulation. With some 6,500 single finds recorded from England 600–1180, they provide a much larger sample and a broader geographical and chronological coverage than the 250 or so English hoards of the same period (Blackburn and Pagan 1986).

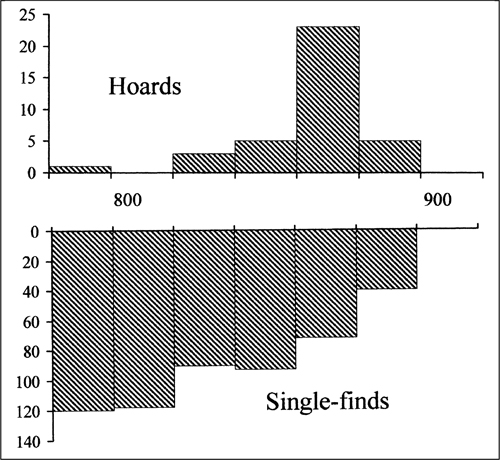

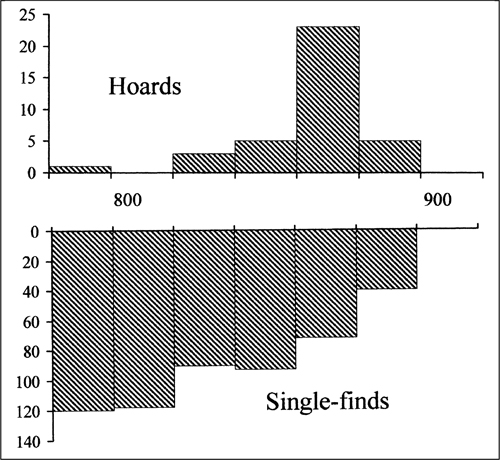

The difference in the data presented by hoards and single-finds is vividly demonstrated in Fig. 3.2, which compares the incidence of hoards (above) with single-finds (below). Single-finds are plentiful during the first half of the eighth century, but become progressively fewer during the later eighth and ninth centuries. The hoards present a very different picture, there being very few in the eighth and early ninth centuries but swelling dramatically in the period 860–80, which coincides with the arrival of the great Viking army in 865 and its campaigns leading up to the conquest and settlement of the Danelaw in the later 870s. This is an unusually clear example of the impact a military campaign can have on the pattern of coin hoards.

In using the single-find data one should be aware of potential problems (Blackburn 1989a). Any coin that has been converted into jewellery by being pierced or mounted should be excluded from an analysis since it had probably ceased to have a monetary function. Some apparent single-finds may in fact come from disturbed graves, though this is really only a potential problem for the seventh century, as the practice of placing coins and other goods in graves died out in England at the beginning of the eighth century, while the few fifth-and sixth-century coins in graves had usually been worn as ornaments. Some coins may be strays from disturbed hoards, although as the number of new hoards found in England is tiny compared to the number of single-finds any distortion of the evidence through the inclusion of the odd hoard coin should be small. That this does indeed appear to be so is indicated by the very different chronological patterns shown by the hoards and the single-finds. Suchodolski (1996) has also warned about the influence of votive deposits, such as coins placed in hearths or foundation trenches, but while this may be a factor in Poland, we have no evidence that such practices were followed in Anglo-Saxon England. Our confidence in the general reliability of the single-find evidence is bolstered by the similar patterns that recur at different sites and in different regions.

FIGURE 3.2. Histogram comparing hoards and single-finds from England, 780–900.

The interpretation of single-finds: geographical and quantitative approaches

The single-find evidence can be used for interpretation in two fundamentally different ways. One is studying their geographical distribution, taking them as evidence that the coins were in use at the places where they were found. The other is a more quantitative and chronological approach, looking at the number of finds from different periods in a particular place or locality.

We can use the geographical distribution of particular coin types to help identify where they were produced and how they subsequently moved in circulation. The simplest way is to plot the findspots on a map or series of maps, but Metcalf has developed a number of sophisticated statistical techniques to present and interpret the data. Thus he has used a form of regression analysis to compare the average distances and directions coins from different mints travelled before being lost (Metcalf 1998a and b; this volume). This showed that in the ninth century, coins from Canterbury and London generally travelled further that those from East Anglia and Wessex, a feature also seen in the eighth century. For the Late Anglo-Saxon period, after c. 973, he has investigated the velocity of circulation of coinage seeing how far coins had travelled during the short period in which each type was valid (Metcalf 1980, 27–31). These methods look at the distribution of coins of a particular type or mint, but one could equally concentrate on the origins of coins found at a particular site, seeing in which direction it had contacts. Thus, the ‘productive’ site in ‘South Lincolnshire’ is exceptional for its high proportion of Continental coins of the seventh and eighth centuries, implying it had a significant role in North Sea trade. However, before drawing conclusions about the significance of a group of finds, one must take into account the normal composition of the currency in that region and the indirect routes by which particular coins might have arrived.

The second approach to single-finds is a quantitative/chronological one. Here we are interested not in where the coins came from, but in how many have been found and what this tells us about monetary activity on a particular site or in a certain region (Blackburn 1989b). Any interpretation must take into account the fact that the rate of recovery of coins from different sites or localities will inevitably differ. The excavation finds from Hamwic have been prolific, yet only some one and a half hectares (three and a half acres) representing 3 percent of the estimated habitation area has been investigated. If the excavations had extended over 10 percent or 20 percent of the settlement, the number of coins found would be very different. Moreover, had the archaeologists excavated the same square metreage but in a different area of Hamwic they might have found very few coins. In the case of metal-detector finds, the sites that have yielded most coins have generally been worked on for hundreds of hours, often over many years, but the rate of discovery varies dramatically from year to year depending on soil conditions and the depth to which the land has been ploughed. The level of finds recording by numismatists or archaeologists also differs from region to region: a recent study of Celtic coins shows an unusually high density of finds in Oxfordshire, which is thought to be due to the fact that the Celtic Coin Index is based in Oxford (De Jersey 1997). Similar biases will undoubtedly have affected the Early Medieval find data.

Because of these factors biasing the sample, conclusions cannot be drawn based on the absolute number of coins recorded from a particular site or region. The data can, however, be used to draw comparisons between periods. A coin of the tenth century should have as much chance of being recovered in excavations or by metal-detector as one of the eighth or eleventh century, and most finders would be as likely to report one Anglo-Saxon coin as any other. There will be some distortions, with very rare coins having a greater chance of being recorded and the commonest ones or cut halves and quarters being passed over by some finders and professionals as being of lesser interest. This will particularly affect Henry II’s cross-and-crosslet issue of 1158–80, which are uniform in type and badly struck. During the twenty years in which Michael Bonser and I have been recording finds we have always impressed on our contacts the need to report every single coin of the period 410–1180, irrespective of its rarity, legibility or condition. Let us start, then, as a control, by looking at three sites where we know that we have an unbiased sample: the excavated coins from Hamwic, and the metal-detector finds from ‘near Royston’ and Tilbury recorded by Bonser and myself.

Hamwic, Royston and Tilbury compared

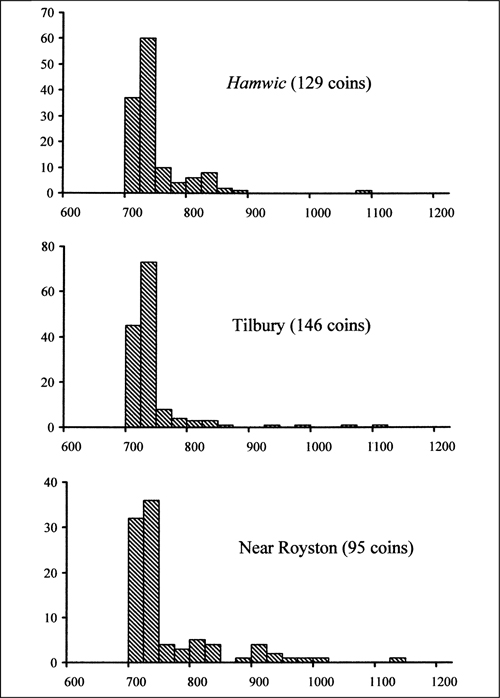

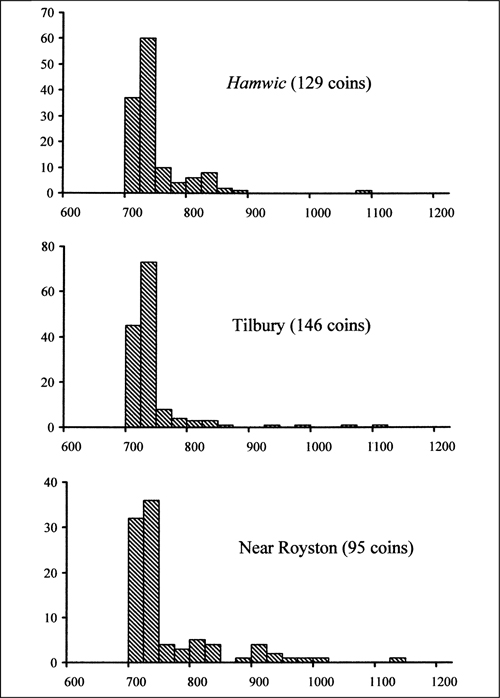

The prolific coin finds from many seasons of excavations at Hamwic form a striking pattern when viewed as a histogram (Fig. 3.3a). This shows a dramatic start at the beginning of the eighth century to very high rates of coin loss which lasted for some forty to fifty years followed by an equally sharp decline in the middle of the century. After this coins continued to be lost at modest levels for another hundred years, before tailing off by the end of the ninth century. Three-quarters of the 129 excavation coins come from the period 700–50. This has been interpreted as indicating that Hamwic ‘rose swiftly to commercial prosperity during the first quarter of the eighth century … and declined again to a much more modest level of monetary exchanges in or before the last quarter of the same century. At that level it survived for at least another 80 or 100 years’ (Metcalf 1988a, 25).

Archaeological evidence indicates that Hamwic was laid out as a town on a new site c. 700, and that it had been abandoned in favour of the defended burh to the west by 900. The coin finds are entirely consistent with this, but how far they can be used to chart the level of commercial activity at Hamwic during the intervening 200 years is something to be considered more closely.

FIGURE 3.3. Finds from Hamwic, Tilbury and ‘near Royston’.

Some 150 kilometres away at Tilbury, on the north bank of the Thames below London, two adjoining fields were a popular hunting ground for several metal-detector users during the later 1980s and ‘90s. Some of them reported their finds of coins and metalwork directly to us, so we have a significant and representative sample even if a much larger quantity of material has been found there. These 146 coins (Fig. 3.3b) present an almost identical pattern to those from Hamwic, with in this case 80 percent of the coins dating from 700–50. No seventh-century gold coins or primary sceattas have been found, but the intermediate sceattas (c. 700–15) are present in good numbers, and only four coins date from after 900. Some Middle Anglo-Saxon metalwork was seen by Leslie Webster but no archaeological survey of the site has been carried out.

Another eighty kilometres north, in a large field on the Cambridgeshire/Hertfordshire borders near Royston, two detector-users have found some 116 Early Medieval coins since 1979. Their histogram (Fig. 3.3c) again looks very similar for the period down to 900, but with a slightly lower concentration during 700–50 (65 percent) because the finds revive in the tenth century with a group of Viking and later issues. The metalwork from the site was not of high status and was predominantly from the eighth and ninth centuries, but continuing into the tenth century. Again, no archaeological survey has been carried out.

If the finds can be interpreted as a measure of general commercial activity, it does seem extraordinary that the fortunes of the sites at Tilbury and Royston should so closely have mirrored those of Hamwic a hundred miles away, despite their differing functions – Hamwic an international port and urban settlement, Royston perhaps a seasonal market serving the rural economy and Tilbury probably bridging local and inter-regional trade via the Thames. Nor do the different political circumstances at the three sites seem to have had a significant effect – Hamwic in Wessex, Royston in Mercia and Tilbury in Essex, the latter subject first to Mercian then to West Saxon domination. The coin types found at each site were rather different, especially during the first half of the eighth century, those at Hamwic being dominated by the locally-produced sceattas of Series H, while Tilbury and Royston had mainly Series K, L, S and Continental E but in differing proportions. In numerical terms the amount of coinage being lost may have been similar, but it was represented by the local currency.

The wider context

A comparable pattern can be traced at sites in East Anglia and Lincolnshire. At Bawsey in Norfolk (Fig. 3.4a) the finds begin somewhat earlier with gold shillings and primary sceattas, but there is still a build up c. 700 and a step down c. 750 into the broad penny period. Coinage is very sparse between the mid ninth and late tenth centuries, but then picks up in the eleventh century. Coddenham and Barham in Suffolk and Caistor-by-Norwich, Norfolk are three more sites that begin in the gold period, have some primary sceattas and many intermediate and secondary ones, but very few broad pennies. ‘South Lincolnshire’ (Fig. 3.4b), Riby and Flixborough are three Lincolnshire sites dominated by Middle Anglo-Saxon finds, the first two having a distinctive seventh-century gold phase, but still with a sharp step up and down c. 700 and c. 750. Flixborough is unusual in having an additional mid ninth-century element, comprising ‘Lunette’ pennies of Burgred, ^thelred I and Alfred and Northumbrian stycas, arguably associated with the presence of the Viking army on the Trent in 872/3 (Blackburn 1993b), and this is certainly the cause of the distinctive pattern of coin and artefacts from Torksey (Blackburn 2002).

FIGURE 3.4. Finds from Bawsey, ‘South Lincolnshire’ and Hollingbourne.

FIGURE 3.5.Finds from ‘near Malton’ 1, South Newbald and Whithorn. The Northumbrian sites have a distinctive pattern due to the large quantity of base stycas circulating in the mid ninth century.

In Kent, the most prolific site, Reculver, produced at least sixty-five sceattas during the erosion of the coastline in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but only a handful of broad pennies. At other Kentish sites broad pennies are better represented, but still sceattas predominate, as at Hollingbourne (Fig. 3.4c) which has four seventh-century gold coins, twenty-six sceattas and nine later pennies mostly of the late eighth or early ninth century. Another site near Canterbury with a similar distribution has yielded one gold shilling, nine sceattas, and nine broad pennies.

The Northumbrian sites, such as South Newbald (Fig. 3.5b), ‘near Malton 1’ (Fig. 3.5a), ‘near Malton 2’, Cottam, Whitby, Carlisle, ‘North of England’ and of course York, have a distinctive pattern of their own, strongly influenced by the circulation of the base and low-value stycas in the ninth century. Into the same mould falls the only ‘productive’ site in Scotland, the Northumbrian monastic settlement at Whithorn (Fig. 3.5c).

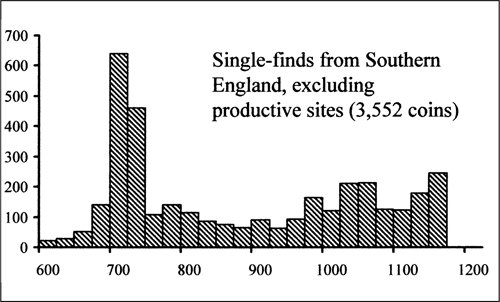

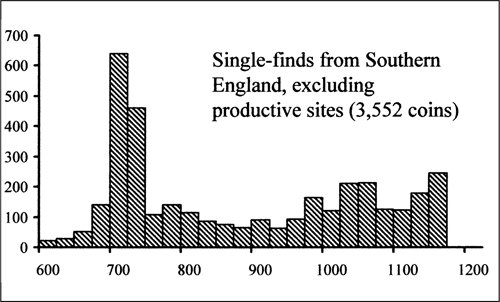

The similarity in the pattern of coin loss at each of the sites we have looked at is too great to be the result simply of ad hoc changes in activity prompted by local circumstances. Could we be seeing evidence not of a change in the function of the sites but of a change in the use of money? Support for the view that these histograms mainly reflect a general monetary trend which is not site-specific is indicated by the pattern of 3,552 isolated finds from southern England excluding those from ‘productive’ sites (Fig. 3.6). The profile of this histogram between 600 and 900 has much in common with those for the sites in southern England discussed above. There is a small but increasing volume of finds during the gold phase, a step up with the primary sceattas in the last quarter of the seventh century, but a far more dramatic increase in the first half of the eighth. The sharp fall in the mid eighth century is just as clear as at the ‘productive’ sites, followed perhaps by something of a revival towards the end of the century, although the third quarter remains one of the most mysterious periods for the numismatist (Metcalf 1988b). For the ninth century, a steady decline in coin finds is seen more clearly among the isolated finds than those from ‘productive’ sites possibly because of the larger sample. After 900 the isolated finds provide a quite different picture, with a fairly progressive increase in the number of finds until the third quarter of the eleventh century, a falling back in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, and a rise again down to the end of the period in 1180. Even so, the highest point in the second half of the histogram is less than half the level attained during the first half of the eighth century. The proliferation of coinage in the early eighth century is one of the most remarkable features of the economy of Early Medieval England, and one we could barely have guessed at before the advent of metal-detector finds.

The histogram in Fig. 3.6 is an important tool, for it establishes a typical pattern of coin finds that might be expected in southern England from ‘normal’ monetary activity. When interpreting the finds from particular sites we should compare them with this control, and only if there are significant differences can we attempt to say something about the specific sites. Thus, the absence from Hamwic, Tilbury and Royston of any coins before 700 appears to be significant, and strongly suggests that those sites were newly established or, at least, changed their nature at the beginning of the eighth century. Their pattern of finds during the eighth and ninth centuries can now be seen to be unexceptional; towards the end of this period the finds are perhaps slightly lower than expected. The significant change for Hamwic and Tilbury comes at about the end of the ninth century and for Royston in the mid tenth century as the finds fail to pick up and match the profile of the isolated finds generally. Of the other sites reviewed, Bawsey, Coddenham, ‘South Lincolnshire’, Riby, Hollingbourne and ‘near Canterbury’ all have a sufficient quantity of early gold coinage to suggest that they had played a similar economic role throughout the seventh and eighth centuries, and possibly from an even earlier date. Some of them, such as ‘South Lincolnshire’, Hollingbourne and ‘near Canterbury’, may have suffered a real decline or been abandoned in the late eighth or first half of the ninth century, while Bawsey continued into the eleventh century. Coins may not have changed hands so frequently on these sites after the mid eighth century, but we should not assume that commercial activities suffered as a result, for other means could have been found to conduct business, such as barter or credit, as they would have been before 700. This view is supported by the finds of metal artefacts from the sites. Those from Royston, Bawsey and Barham were studied by Leslie Webster and Sue Margeson for the 1989 symposium and they reported that there was no parallel reduction in ninth-century metalwork, indeed at Royston and Bawsey this was the most plentiful group and the finds continued at a moderate level into the tenth century.

FIGURE 3.6. Isolated finds from England south of the Humber.

We are beginning to see the characterisation of quite a large number of Middle Anglo-Saxon places where coinage was regularly changing hands and metal artefacts were being dropped. Many of these declined or failed at some point during the ninth or tenth century, and did not develop into Late Anglo-Saxon towns. Today these are mostly located in open fields and have been readily accessible to metal-detector users. By contrast, those that continued to thrive and developed into towns in the Late Anglo-Saxon and later Middle Ages have not been investigated by metal-detector users to the same extent. The finds from towns and cities have often been recovered from small urban excavations and chance finds in gardens or on building sites. To obtain sufficient material to study from towns it is necessary to amalgamate such finds. Not surprisingly they present a very different pattern of finds from the more classic rural ‘productive’ site.

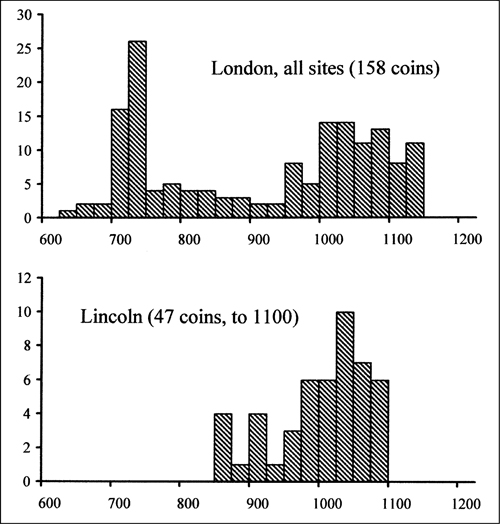

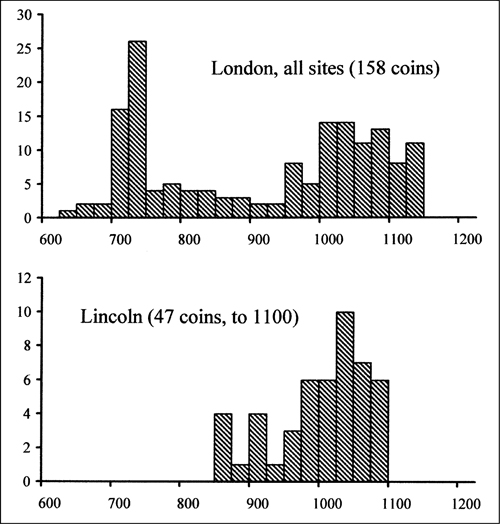

For London, Stott (1991) recorded 158 finds from within the City and from the settlement around Aldwych to the west, and their histogram (Fig. 3.7a) mirrors quite closely that of the isolated finds in Fig. 3.6. The eleventh-century finds are more plentiful than would be predicted from the ‘normal’ pattern, presumably reflecting London’s growing importance as the capital of the newly unified kingdom of England. Yet even this is by a factor of less than two, confirming that in the Middle Anglo-Saxon period London was already a major commercial centre. Lincoln provides an interesting contrast. Archaeologists have yet to find evidence of a Middle Anglo-Saxon settlement in the town, and the accumulated coin finds (Fig. 3.7b) bear out the absence of this phase. They begin in the 870s and reflect the Scandinavian development of the town. If Lincoln had a Middle Anglo-Saxon precursor, comparable to Hamwic for Southampton or Fishergate for York, it must have been located elsewhere. Thetford has yielded many coins from the eighth century onwards, but their distribution is weighted to the eleventh and twelfth centuries as a prolific area of the Late Anglo-Saxon and later medieval town has been extensively investigated.

FIGURE 3.7. Finds from London and Lincoln.

Economic factors

Having traced the changing pattern of coin finds in Early Medieval England, we have to ask what it is that we are really observing. Elsewhere I have argued that the finds reflect ‘monetary activity’ in a broad sense, not only changing hands in transactions but even being carried in people’s purses, for the more money there was on the site, the greater the chance of coins being accidentally lost (Blackburn 1989a and b). The risk of loss could be increased by more rapid circulation of the same amount of money, but the most likely factor influencing it would be the volume of currency in circulation.

There is a well-documented parallel for the expansion and contraction of single-finds in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries. Rigold (1977) observed a dramatic increase and decline in the number of coin finds from excavation sites which coincide with comparable changes in the volume of the English currency (Blackburn 1989a, 19–20; more accurate estimates for the size of the currency now available in Allen 2001 support the same conclusion). The contraction in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was prompted by a general shortage of silver in Europe (Spufford 1988, 339–62). Arguably, we may be witnessing something similar in the Early Middle Ages, with large fluctuations in the amount of available silver as new sources were found to replenish the existing stock that was constantly being eroded. The dramatic rise in coin loss c. 700 took place at a time when the coinage of Frisia (sceattas of Series E and D) was expanding rapidly and flooding into England, where much of it was melted down and restruck as Anglo-Saxon sceattas (Grierson and Blackburn 1986, 152–4 and 167–9). New sources of silver had probably been discovered in central Europe, possibly in the Harz mountains in north Germany, fuelling the expansion of the coinage in north-west Europe in the first half of the eighth century. However, a debasement in the fineness of the silver sceattas during the second quarter of the eighth century apparently heralded a major contraction in the currency. In the mid ninth century a general shortage of silver is again suggested by debasements observed in the Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon coinages from c. 840 (Metcalf and Northover 1985 and 1989); in Northumbria it started earlier and was far more severe. Significantly, the ninth-century decline in single-finds found in England is also echoed in the finds from the Low Countries and Germany (Blackburn 1993a). There are other parallels; a number of sites, such as Domburg, Dorestad and Schouwen Island, thrived in the eighth and ninth centuries but then faded, just as many of the English ‘productive’ sites did. It seems, then, that we are really looking at common European economic trends.

Other aspects of this apparent contraction should be explored elsewhere. Die-studies of the coinage can shed light on the relative mint output, and these need to be brought into any consideration of how the economy operated. The price of silver will have varied with supply and demand, and so too the value of the penny. Historians should be aware, then, that a penny in the early eighth century is likely to have bought much less than one in the later ninth century. The new body of single-find evidence has provided us with a powerful tool for the study of the economy in the Early Middle Ages, but it is one to be used with considerable care.

Appendix: the principal ‘productive’ sites in Britain

Barham, Suffolk (50+ coins) (unpublished; 44 on EMC)

Bawsey, Norfolk (124 coins) (unpublished; 40 on EMC)

Bedford, near (19 coins) (unpublished; EMC)

Bidford-on-Avon, Warwicks. (14 coins) (Wise and Seaby 1995)

Brandon, Suffolk (20+ excavation coins) (unpublished)

Caistor-by-Norwich, Norfolk (23 unpublished, 19 sold Christie’s 4.11.1986, lots 354–72)

Cambridge, near (15 coins) (Blackburn and Sorenson 1984)

Canterbury, near, Kent (19 coins) (Bonser 1997, 41)

Carisbrooke (area), Isle of Wight (15+ coins probably from a single site) (Ulmschneider 2000a, 171–2)

Carlisle, Cumbria (61 coins, various sites) (Pirie 2000, 49 and 76–7; EMC)

Coddenham, Suffolk (33+ coins) (unpublished; some Sotheby 4.10.1994)

Cottam, near Sledmere, N. Yorks. (40 coins) (Pirie 2000, 44 and 62)

Flixborough, Lincs. (53 coins, excavation and detector finds) (Blackburn 1993b, 87)

Hamwic (Southampton), Hants. (I34 coins from several excavation sites) (Metcalf 1988a)

Hanford, Dorset (18+ coins) (unpublished)

Hollingbourne, Kent (39 coins) (Bonser 1997, 41)

Ipswich, Suffolk (c. 145 coins from several excavation sites) (unpublished, some on EMC)

Lincoln, Lincs. (47 coins from various sites) (Blackburn, Colyer and Dolley I983; unpublished additions)

London (158 coins from various sites) (Stott 1991; EMC)

Malton, near, N. Yorks., site 1 (35+ coins) (Bonser 1997, 42)

Malton, near, N. Yorks., site 2 (57+ coins) (Bonser 1997, 42–3)

‘North of England’, E. Yorks. or N. Lincs. (112 coins, many unrecorded) (Bonser I997, 43–4)

Ravendale, West, Lincs. (12 coins) (Blackburn and Bonser 1984b; Blackburn I993b, 88 (‘near Grimsby’)

Reculver, Kent (73+ coins) (Rigold 1975; Rigold and Metcalf 1984; Metcalf 1988c)

Riby, near, Lincs. (28+ coins, few described) (Ulmschneider 2000a, 146; EMC)

Royston, near, Herts./Cambs. border (116 coins) (Blackburn and Bonser 1986; Bonser 1997, 44; EMC)

‘South Lincolnshire’ (141 coins) (Bonser 1997, 41–2; EMC)

South Newbald (‘Sancton’), S. Yorks. (126 coins) (Booth and Blowers 1983; Booth 1997)

Thetford, Suffolk (various sites) (109+ coins) (Blackburn and Bonser 1984a, 69–71; EMC and unpublished)

Tilbury, Essex (146 coins) (Bonser 1997, 44–5)

Torksey, Lincs. (50+ coins) (Blackburn 2002)

Whitby, Yorks. (169+ coins from 1920–8 excavations and other finds) (Rigold and Metcalf 1984, 265; Pirie 2000, 45 and 66–7)

Whithorn, Wigtownshire, Scotland (66 coins from excavations) (Pirie 1997)

York (150+ coins) (Pirie 1986a and 2000, 40 and 54–6; EMC)

* The histograms illustrated in this article are intended to reflect the likely date of loss of the coins, rather than their date of striking. To achieve this a simple adjustment has been made to the data, assuming that one third of the coins struck in any 25-year period remained in circulation until the following 25-year period, with the proviso that no coins were carried past the years c. 760, c. 792, c. 850, c. 862, c. 865, c. 875, c. 880, c. 973, etc., when fairly comprehensive recoinages appear to have taken place. Some of the histograms are based on a smaller sample of coins than the totals indicated in the Appendix, for reasons of consistency, reliability of data or convenience.