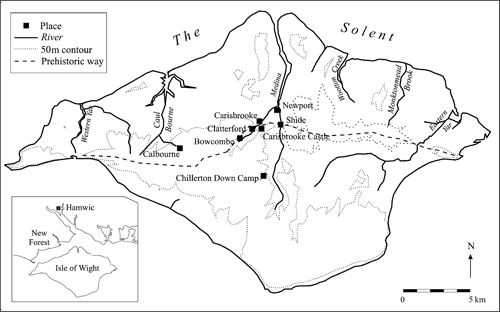

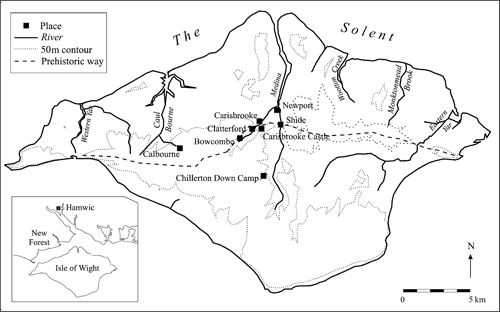

FIGURE 7.1. The location and geography of the Isle of Wight.

For many years research on Middle Anglo-Saxon trade in the Solent area has focused mainly on the great emporium at Hamwic. This is not surprising given the quantity and variety of finds from this important trading place, its recording as a mercimonium in the eighth-century Vita Willibaldi, and its wide European contacts (Morton 1992; Andrews 1997; Bauch 1984, 40–1). However, it is clear from the same written source that Hamwic was not the only market in operation at that time. When, in about 721, Willibald set out on his travels to a place near Rouen, it was not from Hamwic, but from a place nearby, which in Hugeburc’s Vita Wynnebaldi was described as another mercimonium at Hamblemouth (Bauch 1984, 136–7). Unfortunately this market and shipping place at present remains undiscovered, but it serves as an important reminder that other trading places would have existed alongside the major coastal emporia.

Indeed, archaeological support for such likely trading sites is now increasingly being provided by metal-detector finds, which have led to the identification of ‘productive’ sites in many parts of eastern England (Ulmschneider 2000b, 62–3; authors in this volume). This paper, based on a study currently being undertaken on the Isle of Wight, charts the development of such a metal-detected ‘productive’ site in the south of England. It will begin by reviewing the current archaeological evidence from the site, before attempting to answer questions about how, when, and why this site may have evolved, and about its role and importance within the wider area.

The first thing to notice about the site, and a characteristic of nearly all ‘productive’ sites, is its striking location, situated in the centre of the island close to major lines of communication (Fig. 7.1). The site lies in the Bowcombe valley, near Carisbrooke, in an area of great geographical importance. In this area the central chalk ridge, running approximally west to east across the island, is intersected by river valleys accommodating important north-south routes. The major land route from the west to the east of the island, believed to have been in use since prehistory, ran along the crest of the ridge and descended near Bowcombe to cross the valley of the Lukely Brook, formerly the Carisbrooke (Ulmschneider 1999, 23). It is not known exactly where this crossing point might have been in the Anglo-Saxon period, but an important ford, one of three in the valley, survives at Clatterford near to our site, where there are also the remains of a substantial but largely unexplored Roman villa (Basford 1980, 31, 33 and 123). Having crossed the brook, the route would have continued eastwards, crossing the River Medina at another major ford near to the better-known Roman villa at Shide (ibid., 31–3 and 129; Tomalin 1977), before climbing to continue along the chalk ridge. The site can thus be seen to lie in the immediate vicinity of the crossing of a minor tributary of the Medina by the most important west-east land route across the island, and to have good communications to an agriculturally rich hinterland via the river valleys. The twelfth-century town of Newport, about three kilometres from the site, lies at the head of navigation of the River Medina, from which point the river provides a major shipping route into the Solent and beyond.

FIGURE 7.1. The location and geography of the Isle of Wight.

The second important characteristic of this, and other ‘productive’ sites, is the large amount of Middle Anglo-Saxon coinage they produce. When finds from the site were first discussed in 1999, there were certainly nine, and probably as many as eighteen coins attributed to it, making it more coin productive then any other site in Hampshire, apart from Hamwic (Ulmschneider 1999, 30–3, with detailed literature on the published finds). Since then, co-operation between two of the finders, archaeologists on the island, and Michael Metcalf has doubled this number to thirty-seven or thirty-eight finds (M. Metcalf, pers. comm.), making this ‘productive’ site completely unique for the whole area. These finds immediately raise some very important questions: when, how, and why did this site start, what were its connections, and when and why did it cease to function?

A detailed assessment of the coinage is currently being carried out by Metcalf (M. Metcalf, pers. comm.), but a few observations may be made. Of the thirty-seven finds, eleven are silver sceattas of Series E and two of Series D. All originated from the area of the Rhine mouth, while one further find, a sceatta Series X, originated from Jutland. The coins of Series D and one of the seven specimens of Series E which were available for examination, are of primary date i.e. before c. 710–15, although their date of loss may have been later. Other Continental finds comprise one Merovingian denier, and perhaps a very rare Series E Type 12/5 ‘mule’. The second largest group in the assemblage is formed by sceattas of Series H, minted at Hamwic. These comprise seven coins, one of them of the early Secondary Type 39, five of the later Type 49, and one which still needs identification. Of the remaining thirteen finds, twelve are English sceattas of Series C2, F, H Type 48, J, O, R derivative, V, W and a Series W related mule, four of them primary, the rest secondary. Finally there is a penny of Offa, and possibly yet another sceatta, Series O Type 38.

Coin use on the site therefore appears to have started late in the primary sceatta phase, perhaps from around 700–10 onwards, when both Continental and English issues reached the site. This coin use intensified greatly during the course of the eighth century but seems to have declined towards the end, following a general pattern of decline found at other sites of the period (Blackburn, this volume; Grierson and Blackburn 1986, 155–89; Metcalf 1988b, 230–53). However, there appears to have been no re-generation of coin use on the island site, which appears to have ceased, or moved to another place, by the early ninth century.

The origins of the coins also indicate a wide range of connections. Among them, the most important one appears to have been with the Rhine mouths area, and probably Dorestad (Metcalf 1993–4, 170–81). However, we cannot assume that all of these coins would have necessarily arrived directly from the place they were minted, although this seems likely for those from Hamwic. Perhaps more significant is the number of unusual or extremely rare finds. These include, amongst others, the Merovingian denier (unpublished) and the two sceattas of Series R derivative (Coin Register 1993, 147 No. 177), currently the only ones of their type known in Hampshire. The really outstanding finds are the Series E Type 12/5 mule, probably of Continental origin (Ulmschneider 1999, 39–40 and fig. 6e), and the Series W related mule (unpublished). Both coins are extremely rare. Only two other specimens of the Series E mule are known at all, one of them on the Continent, and all three from the same dies (Metcalf 1993–4, 531 and 536), while there is only one other, unpublished, find of the Series W related mule (M. Metcalf, pers. comm.). From this preliminary analysis it is already becoming clear that we are dealing with a very important ‘productive’ site, a picture which is now beginning to be mirrored in other find categories.

The third characteristic of this and other ‘productive’ sites is that they invariably produce other non-ferrous metalwork, and sometimes unusual high-status finds. In 1999 one strap-end was known to have come from this site (Ulmschneider 1999, 39–40 and fig. 6d), but since then it has become clear that other finds have been made during the last decade, and there is now a pressing need to establish a full corpus of these objects. One such new find, very kindly brought to my attention by Leslie Webster, is a very unusual copper-alloy fitting with a runic inscription, now in the possession of the British Museum (L. Webster, pers. comm.; BM Acc. No. 1999.4–1.1). The object, still unpublished, is of eighth-to ninth-century date, but its function currently remains unknown. It seems highly likely that we have not yet seen the full range of finds available from this site. This may also be underlined by a surprising lack of pins so far, which are almost always found on other ‘productive’ sites (Ulmschneider 2000a, 32, 51 and 60, and maps 6 and 22).

Interestingly, it is now also becoming clear that the site is producing a scatter of finds from many other periods, for example Roman coins, brooches, and even some pottery (Isle of Wight SMR 2161 and 2156). There was clearly a focus of Roman activity in the valley (Fig. 7.1), and three Roman villas are currently known: at Carisbrooke, Clatter-ford, and Bowcombe (Basford 1980, 123). This focus appears to have continued in the Early Anglo-Saxon period, for which important high-status burials with outstanding Merovingian objects are found at Carisbrooke Castle (Morris and Dickinson 2000, 86–97), and on Bowcombe Down (Stedman 1998, 115–18). Early Anglo-Saxon finds, including brooches, have also been reported from the same two or three fields as the ‘productive’ site, together with Medieval, and many other, undated finds (Isle of Wight SMR 2161, 2156, 2388). Unfortunately, the information provided at present does not allow the identification of different foci of activity within the fields, which await fieldwalking.

Current evidence therefore points to a major market or ‘productive’ site in an area of very dense activity in the centre of the island, which clearly had close connections with both Hamwic and probably the Continent. Perhaps one of the most intriguing questions surrounding this site is: why is it located in this particular place? Here answers may be provided by the surrounding landscape (Fig. 7.2).

One possible explanation for its location, which has already been touched upon, is that the valley was clearly a centre of communications and activity from a very early date (Fig. 7.1). A few kilometres to the south is the only definite Iron Age hillfort on the island, at Chillerton Down (Basford 1980, 27 and 121; Dunning 1947). Then, during the Roman period, three – or including the Shide villa, four – of the eight known villas on the island were concentrated here (Tomalin 1987, fig. 1). From the Early Anglo-Saxon period, two very important cemeteries with Merovingian imports are found, one of them possibly within a highly tentative Late Roman enclosure (Young 1983, 283–4 versus Rigold 1969; Young 2000, 12, 18 and 190–1). There was also an important ford and crossing point of major routes in the valley.

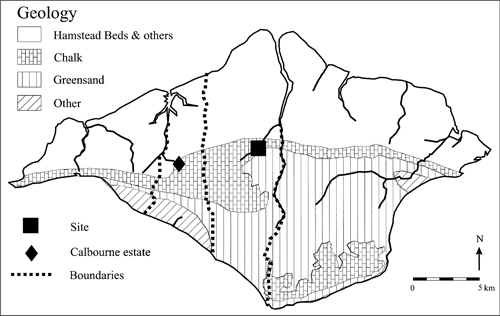

FIGURE 7.2. A simplified map of the geology of the Isle of Wight. Estate boundaries indicate the early use of different geological zones.

However, there may have been other reasons influencing the choice of site. Why, for example, was it not located at the second important fording point at Shide in a possibly even better geographical position, or indeed lower down the Medina, where it becomes navigable? Here the local geology and soils (Fig. 7.2) may provide some important clues. Unlike the largely infertile sands and clays following much of the lower valley of the Medina (Hamstead Beds and others), the ‘productive’ site was situated in a rich agricultural and pastoral landscape where the downlands meet the fertile greensands (Welldon-Finn 1962, fig. 90; Bird 1997, fig. 1). This location in an area where large blocks of very different soil types meet is of great importance, as the site would have been able to exploit two or probably three major ecological zones. This practice may have originated much earlier (see Fig. 7.2), and is perhaps preserved in the boundaries of the ninth-century Calbourne estate (Sawyer 1968, No. 274), and the territories from sea to sea of the early churches at Domesday (Hockey 1982, 1–8, map inside cover for parish boundaries). Not only was the site situated at the junction of three major ecological zones, it also lies in an area where porous chalk meets with less permeable greensand formations (Geological Survey, Drift Sheet 330). In these areas freshwater springs often break out, and at least two springs are known within the close vicinity of this ‘productive’ site.

This preliminary assessment of the surrounding landscape therefore seems to argue for a ‘productive’ site heavily involved in the exploitation of natural resources. But what were they? While the wooded north of the island is likely to have been used, among other things, for pig-rearing, hunting, and as a source of timber, the chalk downs would have been very well suited to sheep farming. But perhaps the most important resource was the loamy greensands in the south. These provided excellent soils for grain and were intensively exploited throughout the Roman period and in the later Middle Ages (Isle of Wight County Council 1992, 24; Hockey 1982, 105–8).

Of potential importance here may be the only pre-Conquest record of a mill on the island, at Bowcombe in a charter of 964X975 (Sawyer 1968, No. 821; Kemble 1839–48, No. 599). Unfortunately, the charter is complicated, and the mill may not actually have stood in Bowcombe itself but within its hundred (Finberg 1964, No. 109 at 51–2, 97–8 and No. 352 at 107–8). Nevertheless, the general idea deserves serious attention. In Domesday Book two mills are recorded at Bowcombe (DB Hampshire, fo. 52b), which has been identified with Carisbrooke (Margham 1992), and at a later date at least two are known to have belonged to Carisbrooke castle and the priory (Hockey 1982, 239). Also intriguing, although maybe completely co-incidental, is the record of an eighteenth-century paper mill in the immediate vicinity of the ‘productive’ site, marked on the 1864 first edition Ordnance Survey 25” map (sheet 95.5). Could it therefore have been grain, milled or un-milled, that was purchased by the Hamwic sceattas? The island greensands provide the only soils of their type in the Hampshire Basin (Welldon-Finn 1962, fig. 90), and such perishable foodstuffs could have quickly and easily been shipped down the Medina.

If we are to understand the full significance of this site in the future, it will also be necessary to look more closely at its wider context (Fig. 7.3). One line of enquiry that immediately springs to mind is the relationship between the ‘productive’ site and the emporium at Hamwic. How did these trading sites compare and differ? What were their respective origins, functions, and were they in competition?

FIGURE 7.3. Coin-productive sites and markets around the Solent.

Again a few trends may be suggested. As noted above, the large number of Hamwic sceattas found on the island site clearly indicates a strong trading connection with the emporium, particularly from the second quarter of the eighth century onwards. Both sites also show large numbers of coins from the Rhine mouths area (Metcalf 1988a, 19–20 and 37–9), some of them probably arriving directly from their place of origin, although it could be argued that the Isle of Wight finds may have arrived via Hamwic. Indeed, as far as can be said at present the ‘productive’ site does not seem to have pre-dated the emporium (M. Metcalf, pers. comm.). Neither is there any evidence to suggest that it would have had an active mint-place of its own (Metcalf 1988a, 18–19), being, it seems, largely under the monetary influence of Hamwic. However, this is not to say that all its contacts would have necessarily led via the emporium. Not only is there a small, but probably significant, number of sceatta types from the island that have not yet been paralleled in over 130 sceatta finds from Hamwic, or indeed the rest of Hampshire (such as Series R derivative, O Type 38, and F variety b: Ulmschneider 2000a, Appendix 2; Metcalf 1988a) – there are also the two extremely rare ‘mules’, of which only one or two other specimens are known at all.

While Hamwic out-lived the ‘productive’ site (Metcalf 1988a, 22–5 and 52–7), both markets must have operated side by side for about a century, and despite their possibly different outlooks, the Isle of Wight site would always have remained closely connected with the mainland of Hampshire. Indeed, important trading and shipping routes existed across the Solent, and from the Roman period onwards there is evidence for the transport of goods such as stone, salt, grain, and probably wool from the island (Ulmschneider 1999, 33–6).

Not all traffic of goods would necessarily have been connected with trade. Some of the high-status objects on the island may have arrived as a result of gift-exchange, while other commodities are likely to have been redistributed to supply different parts of large estates. Here another important line of enquiry, which has not received much attention, is provided by the early manorial relationships across the Solent. The evidence provided by eleven Anglo-Saxon charters referring to the island (Sawyer 1968, Nos 274, 281, 543, 766, 821, 842, 1391, 1507, 1581 and 1662–3) and Domesday Book is complex, and points to many changes taking place during the later Anglo-Saxon period. Nevertheless, there is a likelihood that some of the Domesday entries may indicate more ancient ties. For example, there appears to have been a strong connection between the island and the New Forest area on the mainland (Fig. 7.1 inset; Fig. 7.3), with five New Forest manors recorded holding land in the Isle of Wight, and another manor apparently being held from the island (Eling, Holdenhurst, Ringwood, Braemore, Twynham, and Stanswood: Welldon-Finn 1962, 291; Golding 1989, 18–21). Of these, the entry for the church at Tywnham, later Christchurch, claims that the Isle of Wight lands had ‘always been’ in the lands of the church (DB Hampshire, fo. 44b).

Could these entries reflect even earlier connections? (Fig. 7.3) When the West Saxon king Csdwalla conquered the Jutish Isle of Wight in 686, two young princes are reported by Bede to have fled to a place called Ad Lapidem (Historia Ecclesiastica, iv. 16), which has been identified as Lepe in the New Forest, in what would have been the adjoining mainland territory of the Jutes (Yorke 1989, 90). Estate ties between the island and mainland are also attested in a charter of 826, which records the grant of a large estate at Calbourne (see above) to the bishop of Winchester. One therefore must assume a fairly regular network of contacts and flow of goods between parts of royal and ecclesiastical estates in the two areas, and it seems likely that other landing and probably market places would have existed.

Perhaps one of the most interesting questions is how and why this ‘productive’ site came into being. At present it appears from the coinage that the market would most probably have been established, or started to function, fairly shortly after Csdwalla’s conquest of the island in 686, in the immediate aftermath of which a quarter of the Isle was given ‘for God’s use’ to Bishop Wilfrid (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, s.a. 686; Historia Ecclesiastica, iv. 16). Patrick Hase has long argued for the existence of an early mother church for the island at Caris-brooke, the ancient rights of which are preserved in the Cartulary of Carisbrooke, and the parochia of which by the twelfth century still appears to have comprised the vast area from sea to sea between Northwood and Shorwell/Chale (Fig. 7.2; Hase 1975, 323–33; Hockey 1982, 1–13, map in cover). Could the ‘productive’ site have been associated in some way with the foundation of an early mother church in the area? The suggested date of its foundation would certainly be consonant with that of five other mother churches around the Solent in the late seventh to early eighth centuries (Hase 1988, 45–8 and fig. 9). Unfortunately, in the absence of any corroborative written or archaeological sources, the evidence must remain highly speculative and entirely circumstantial.

There is no further information about the area until Domesday, when Bowcombe was the site of the most important royal manor and hundred on the island, encompassing a church, mill, salt-house, and a toll worth thirty shillings. All the tithes of Bowcombe belonged to this church, to which were also attached a second mill and twenty smallholdings, inhabited by bordars (DB Hampshire, fos. 52b and c). Both the presence of the bordars as well as the toll all point very strongly to the existence of a market at Carisbrooke in the Late Anglo-Saxon period (Dyer 1985, 100–1).

Where would this market have been located? There is certainly no evidence at present to suggest a continuation of the ‘productive’ site. So did it shift to another site? The only Late Anglo-Saxon coin so far known in the area is a penny of ^thelred II (985–91), found at Carisbrooke Castle car park. However, the find is said not to have been in situ, and may have arrived in soil carted from Newport ( Jones 1959, 157–9). As the excavated remains of substantial timber buildings attest, the later castle site was clearly important during the Late Anglo-Saxon period (Young 2000, 53–5 and 191–2), but other places also need to be considered, not least areas in the vicinity of the priory church, on the opposite site of Lukely Brook.

Finally, a third line of enquiry must focus on the relationship between the island and the Continent. It is now becoming increasingly clear from its burials that perhaps already by the late fifth, but certainly during the sixth century, the ‘Jutish’ Isle of Wight exhibited considerable wealth and wide trading connections (Arnold 1982a; Morris and Dickinson 2000). Equally significant are the historically and archaeologically well-attested links between the Jutish island, the Jutes of Kent, and the Continent, at a time when both Kent and the Isle of Wight appear to have held a monopoly of southern cross-Channel trade (Historia Ecclesiastica, i, si5; Huggett 1988; Welch 1991). But what were the routes in operation, and how did they change over time? Their continuing use is now reflected both in archaeology and in early written records which, at least from the late seventh or early eighth centuries onwards, point to the growing importance of travel routes to Northern France and the Seine area (Le Maho, this volume; Johanek 1985, 222–5 and 234–44), Willibald’s ship perhaps being bound for the important early fair at Saint-Denis (Bauch 1984, 40–1 and 136–7).

In conclusion, there is now evidence for a major ‘productive’ site evolving in an area that commanded important coastal routes and cross-Channel links from the earliest times. Access to these, as has been argued elsewhere, was probably one of the foremost reasons for the final West Saxon conquest of the formerly Jutish areas by the late seventh century (Ulmschneider 1999, 36–8). By the early eighth century, a number of trading posts existed in the area (Fig. 7.3), including the major emporium at Hamwic, the landing place at Hamblemouth, the ‘productive’ site on the Isle of Wight, and possibly other places, such as one recorded as ‘South Hampshire’, perhaps south of the New Forest (Rigold and Metcalf 1977, 47). In addition, Metcalf has suggested that the minting place for the West Saxon coinage of Series W may have to be sought in this area or a little further west (Metcalf 1993–4, 152–7 and 684), while ninth century coins are now emerging from a site at Eling Creek, Totton (Dunger 1997; EMC 1999.0098). Are we therefore beginning to observe a network of markets in operation, each seemingly bound to a major inlet?

More research is needed, particularly on the chronology and interaction of these sites, before any such pattern can be proposed more confidently. Future research will also have to try to explain two other important observations: First, why, despite much metal-detecting activity, have ‘productive’ sites on the scale of those in the eastern counties not been discovered in the south of England (Ulmschneider 2000a, 107 and maps 5 and 21)? Second, how can the outstanding wealth of the Isle of Wight ‘productive’ site be explained? Apart from Hamwic, no other sites anywhere near its scale are known along the south coast, or within a fifty-mile radius inland (EMC, December 2000). Probably the most important explanation, cross-Channel trade, has already been suggested, but other factors also need to be considered such as the strategic position of the island, which provided important access to Winchester and the Thames Valley – a fact not lost on the Vikings (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, s.a. 897 [896], 998 and 1001). Ultimately, part of the answer may also lie in the nature of Southampton Water and the Solent itself. Could some of these multiple markets have supplied ships or fleets anchored in and around the greatest natural harbour on the south coast?